Muslim democratic parties (MDPs) have recently emerged in the Middle East and North Africa as distinct political entities. Among such parties are the Wasat Party in Egypt (1995), the Party for Justice and Development in Morocco (1998), and the Justice and Development Party (AKP) in Turkey (2001). Despite the fact that most members of MDPs have a past in political Islam, MDPs are categorically different from Islamist parties. Resembling European Christian democratic parties, MDPs differ from Islamist parties on several grounds. First and foremost, MDPs have a methodical attachment to democracy. Unlike Islamist parties, democracy has an intrinsic value for the Muslim democratic political platform.1 Islam is also an important element of the MDP platform, yet in a dramatically different way than in Islamist parties. While Islamist parties have Islam at the center of their political discourse to the extent that they claim to represent and speak on behalf of Islam, MDPs have no claim to represent Islam. Instead, members of MDPs speak as individuals and try to promote Muslim values prevalent in their respective societies.2 The emphasis on Muslimness rather than on Islam fits squarely with the role democracy assumes in the MDP platform, i.e. the notion of pluralism and tolerance on other views and perspectives. In this regard, the end-goal is not the creation of an Islamic institutional structure à la political Islam, but rather the promotion of values and ideas commensurate with a Muslim identity.

The economy constitutes another key component of the MDP platform. In sharp contrast to the highly nationalist and protectionist economic perspectives of political Islamists, Muslim democrats opt for a liberal economic system with no more than a regulatory role for the state in the economy. Such a liberal outlook on the economy, however, does not prevent MDPs from offering extensive networks of social services similar to those proposed by socialist parties. The unique combination of pro-liberal economic stance and emphasis on social services provision puts MDPs alongside the Third Way in Europe.3

Although it would be easy to argue that yesterday’s Islamists are simply flowing with the wind today in order to reap the benefits, it becomes important to note that not all of these parties become successful in their moderation ventures. Hence the issue is not simply one of going with the wind, but rather knowing the conditions that make the way for a successful transformation. Overall, the shift in discourse seems to be a substantial transformation for the former Islamists, which raises the question of what might account for such a radical change.

The literature largely treats this transformation as a top-down process. For many scholars of the Middle East, politics is an elite business, and change happens at the top and is then followed by society. Hence, society is on the receiving end of this moderation. Three theories in the literature are promoting this perspective by stressing the importance of a) inclusion-moderation,4 b) social learning,5 and c) strategic interaction.6 I suggest, in contrast, that society is the engine of change and moderation, which in turn leads to the change in the discourse of Islamists. Then, the critical question is how does the change in society come about?

Economic Liberalization and Center-Periphery Relations

Political Islam, in its essence, is a reactionary response to the exclusion of peripheral groups from political, social and economic arenas

I argue that economic liberalization leads to social moderation, which eventually results in the rise of MDPs. Economic liberalization has often been seen to have the potential to reshape the political landscape towards a more liberal and democratic system.7Policy recommendations in the last decade or so have focused on how the economy has priority over politics in order to shape the latter. According to Fareed Zakaria, economic liberalization should take priority in reform efforts due to its potential to create a middle class business group with “a stake in openness, in rules, and in stability.”8 It is this vested interest of the new business class in a liberal order that will ensure liberalization reforms stay on course. Even though Zakaria and others point to an important dynamic, the explanation suffers from underspecification. The absence of a thorough account of the interaction between economic liberalization and distinct social groups does not help in conceptualizing the relationship. More specifically, the role of the Islamic constituency, i.e. the social base of Islamist parties, which is often identified as the non-moderate element of the Middle Eastern societies, needs to be identified. Another aspect of the relationship is the size of this new business group. How large should the new business group be in order for it to have a significant impact on the liberalization process? If, for example, only a handful of businessmen benefit from openness, would we be bound to see the continuation of “business as usual” between business and state simply because the limited group of businessmen would not depend on openness, but on the state?

In order to address the underspecified relationship between economic liberalization and social groups I consulted the literature on social cleavages. The recourse to cleavages is crucial because social cleavages offer invaluable information on sources of conflict within a society as well as the potential for the politicization of these issues in the political sphere via political parties. Şerif Mardin9 has been one of the pioneers in conceptualizing social cleavages in Turkey to conduct political analysis. The model Mardin offers deals in essence with the distribution of socioeconomic power in the Turkish state and society from the nineteenth century to the twenty-first century, and its reflection on the political space. Throughout the modern era, sociopolitical conflict in the Ottoman Empire and the Turkish republic was shaped by the competition between two groups, rightly claims Mardin, the center and the periphery.

According to this framework, the center of society is composed of the secular elite who have authority over the political system and the economy, and who portrays itself as the sole perpetrator of modernization. In this regard, distinct social elements such as the political elite, the bureaucracy, the military, big business, and urban middle and upper classes are all parts of the center. Secularism has been the identifying characteristic of the center. The periphery, on the other hand, is not a homogenous bloc; different elements of the periphery, be they cultural, ethnic or socioeconomic, largely identify themselves within the encompassing umbrella of Islam. The periphery is left out of the political decision-making mechanism and the economic suzerainty of the state, and is on the recipient end of modernization, living mostly in the suburbs of major cities and rural areas.10 Small and medium enterprise (SME) owners, in this regard, constitute an important element of the periphery. Essentially, peripheral groups are identified and unified by their exclusion from the political and economic system.11

While Islamist parties have Islam at the center of their political discourse to represent and speak on behalf of Islam, Muslim democrat parties have no claim to represent Islam

The initiation of economic liberalization, defined as the minimization of government involvement in the economy in favor of private enterprise, has fundamentally changed the contours of the future course of politics. Building on the discussion above, the way in which a country liberalizes its economy shapes the later form of social cleavages, and more importantly the social foundations of Islamist politics. How a country liberalizes economically has considerable implications over the effects of liberalization in many other policy areas.12

Chaudry’s critique of neoliberal accounts is enlightening in this regard: “[the assumptions embraced] kept them from appreciating the interest political and economic elites may have in forestalling the creation of functioning national markets. Creating markets is politically dangerous. Functioning markets provide opportunities for mobility that undercut lineage and traditional rights of privilege, thus threatening the status quo. Markets create inequalities in wealth that may not match existing patterns of income distribution, status, power, and entitlements; they dislocate groups in both the political and economic realms.”13 The dirigisme rampant in the region foils purely economic perspectives in conceptualizing the economic liberalization process. In order to present a fuller picture, I emphasize the political aspect of liberalization and how social cleavages interact with the liberalization process. To this end, I distinguish between two types of economic liberalization: Competitive liberalization and crony liberalization.

Competitive Liberalization

Competitive liberalization implies the form of economic liberalization characterized by its wide reach in society and entails extensive changes in the distribution of economic power in the society. The more inclusionary and broad-based economic liberalization is, the larger the reach of the benefits of liberalization will be. This is partly because liberalization involves high-level participation of peripheral economic groups, i.e. SME owners, in the process and in the gradual growth. Peripheral businesses no longer face most of the political and economic obstacles they once did, which enables them to engage with the global economy. Pre-liberalization socioeconomic status quo undergoes significant changes as a result. For example, the level of competition in most industries considerably increases. Along the same lines, monopolization decreases over time to allow for greater market access for the peripheral groups. A decrease in monopolization may follow privatization of state economic enterprises and effective ending of state monopolies.

Peripheral groups, and particularly peripheral businesses, certainly become the relative winners of a competitive liberalization process. The implications of this process are substantial. The economy, by its very nature, is the main policy issue peripheral groups develop a strong interest in. As the main beneficiaries, peripheral groups strongly oppose the disruption of liberalization for two reasons. First, the economic well-being and prosperity of these groups depends on the continuation of economic openness. Any policy moving away from liberalization will be harmful to the economic interests of the periphery. Second, interference with the liberal economy would also imply a relative weakening vis-à-vis the big business from the center. In summary, a reversion back to an illiberal economy would mean a relative and absolute loss for the periphery.

Politically, peripheral groups’ renewed interest in democracy underscores the extent of their vested interest in the new system. Commitment to the liberal economy engenders an inherent interest in transparency and political stability, as we would expect from businessmen under similar conditions.14 Contrasted with SMEs’ preference for sweeping transformations of the economic and political system in the pre-liberalization era, their perception of the new economic order highlights this new interest in both political and economic stability. The risks associated with a non-transparent regime leads peripheral groups toward supporting more democratic forms of governance. Because SMEs, in this particular political and economic context, perceive democracy as ensuring the rule of law, fair business opportunities and secure property rights, they have come to have a strong preference for it. Commitment to an open regime is proportional to the risk of loss peripheral groups confront in an illiberal order. The greater the risk they face, the greater the chances of avoiding radical political discourse and of supporting more moderate and transparent political platforms. Since an existential threat to the newly burgeoning peripheral businesses arises when different elements of the center, i.e. bureaucratic and business elite, dominate political and economic power, democracy then offers a better alternative to peripheral businesses than others, such as an authoritarian regime. To reiterate, the preference for a democratic regime is not the outcome of a sudden ideological recognition of democracy’s virtues, but rather because of the potential benefits democracy offers to the interests of the periphery.

The preference for a democratic regime is not the outcome of a sudden ideological recognition of democracy’s virtues, but rather because of the potential benefits democracy offers to the interests of the periphery

As a corollary to the shift in democratic preference, political Islam no longer serves the interests of the peripheral groups. Political Islam, in its essence, is a reactionary response to the exclusion of peripheral groups from political, social and economic arenas.15Far-reaching restructuring of the political and economic system envisioned by Islamist parties aims to secure the integration of the marginalized periphery to the mainstream of the society. When, however, competitive liberalization enables peripheral groups to benefit from the new system, the anti-systemic discourse of Islamist parties for sweeping changes in the state and society would imply political and economic instability and uncertainty, not preferred by peripheral businesses. The set of new preferences of the peripheral groups clearly contradicts political Islam with its reactionary and destabilizing platform. A Muslim democratic platform, however, offers a more reconciliatory discourse along the lines of the preferences of its core constituency. This more moderate platform is a direct response to the change in the periphery, not a defensive move to avoid the center’s reaction.16

Crony Liberalization

Crony liberalization refers to the notion that businessmen, or the economic elite traditionally well-connected to the political elite in a closed economy, are able to maintain their privileged access to the political decision-making mechanisms in the post-liberalization period. The close relationship with the political elite ensures they continue to disproportionately benefit from economic resources and opportunities in the post-liberalization period.17

Two conflicting goals set the stage for the introduction of crony liberalization. Policymakers, facing low levels of economic growth, want to spur economic growth by encouraging integration to the global economy and luring foreign investment. At the same time, the ruling elite want to maintain the mutually beneficial relationship for both sides, that is the relationship between the politicians and the crony businessmen, as before, and to sustain their hold on power.18 As Tarik Yousef argues, the goal is to preserve control over economic and political power: “Many governments of the Middle East had only been reluctant reformers to begin with, and when confronted by political opposition, they adopted policies that weakened the link between economic restructuring and political reform.”19 Wary of the political implications of economic liberalization, many governments have opted for a gradual and strictly controlled liberalization reform process. The political implications of distinct economic liberalizations become crystal-clear once the social cleavages are integrated into the analysis.

Without doubt, political Islam maintains its appeal to the peripheral groups with the existence of crony liberalization. The mere fact that liberalization did not bring considerable prosperity nor elevate the stature of the periphery on relative or absolute terms compared to the center attests to the continued exclusion of these groups from economic and political power centers. A more moderate platform, as in the case of a Muslim democratic one, does not stand a strong chance of survival. After all, the Muslim democratic discourse argues for the stability and continuance of the status quo, things the periphery under crony liberalization deplores.

Parallel to the penetration of economic liberalization in society, Muslim democrat parties manage to expand their support base within the periphery and marginalize Islamist parties

Muslim Democratic Parties in Turkey, Egypt, and Morocco

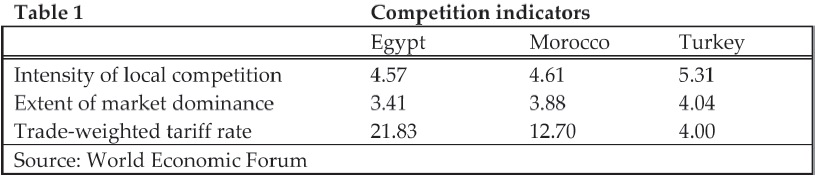

Turkish economic liberalization in the post-1980 era has been qualitatively different from other liberalization process in the Middles East due to its more inclusionary model. More than 98% of the firms in Turkish manufacturing sector since the early 1990s employ less than 50 employees, a significant indicator by any standards.20 In Egypt, in contrast, from the 1980s until the 2000s, the share of firms with less than 50 employees ranged between 73% and 85%.21 Moroccan statistics stand somewhere in the middle as the share of firms with less than 50 employees hovered between 80% and 90% throughout the 1990s.22 In a similar vein, the World Economic Forum’s qualitative evaluation of competition draws a similar picture (see Table 1). Level of competition and monopolization are two of the observable implications of competitive liberalization. The extent of local competition and market dominance measures indicate a more competitive market environment in Turkey compared to Egypt and Morocco, although Morocco stands closer to Turkey. Similarly, trade-weighted tariff rates, which focuses on the actual level of protection in the economy, show that the average tariff rate in Turkey is a mere 4% while the Egyptian tariff rate is almost 22%, and the Moroccan tariff rate is just under 13%. The targeted nature of protection afforded to big businesses particularly in Egypt puts Egyptian liberalization much closer to crony liberalization, whereas the Turkish and Moroccan cases offer lower levels of effective protection to domestic businesses, which places those countries closer to competitive liberalization due to higher levels of competition and lower levels of monopolization. Economic integration with the European Union certainly helps in minimizing the influence of big businesses in Turkey and Morocco.

In a competitive economic and political environment, domestic groups, such as the Islamic political actors, are provided with an opportunity to contest the supremacy of the already-powerful center

The depth and competitiveness of Turkish liberalization also manifests itself in the institutional structure of business associations arising from the peripheral business groups. Business associations such as MÜSİAD (Independent Industrialists and Businessmen’s Association) and TUSKON (Turkey Businessmen and Industrialists’ Confederation) emerged after 1990s as a response to the growing status and demands of the peripheral groups such as SMEs. Detailed analyses have evidenced that such business associations reflect the preferences and interests of their membership.23

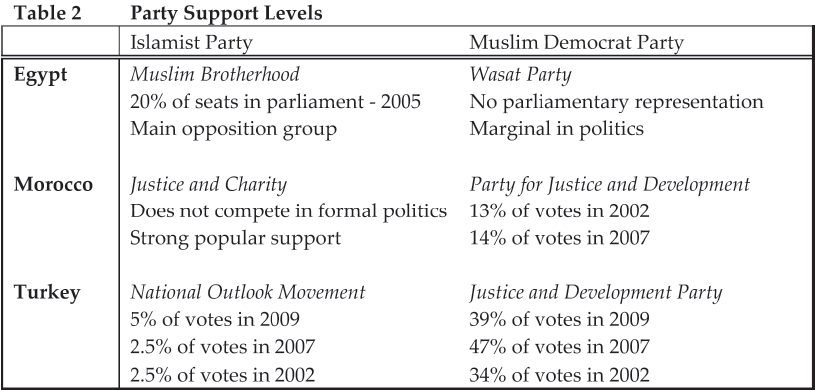

How do MDPs fare in each case? Parallel to the penetration of economic liberalization in society, MDPs manage to expand their support base within the periphery and marginalize Islamist parties (see Table 2). The Turkish case is instructive in this regard. The AKP in Turkey outclassed the well-established Islamist National Outlook Movement only a year after its establishment in the parliamentary elections of 2002. In the successive local and general elections since then, the picture has not changed much. The Felicity Party, the most recent representative of the Islamist platform, remains a marginal party in the Turkish political system attesting to the overwhelming support for AKP by the peripheral groups. The case of the Egyptian Wasat Party is the exact opposite of the AKP. Even though the Egyptian liberalization efforts began about a decade earlier than that of Turkish efforts and the Wasat Party was established in mid-1990s, the relative standings of the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood and Muslim democratic Wasat Party underscore the importance of the type of economic liberalization. After more than a decade, the Wasat Party has not been able to find a strong resonance in the society whereas support for the Muslim Brotherhood has only increased under Mubarak’s limited political liberalization. In Morocco, the Party for Justice and Development (PJD) performs well enough to challenge the dominance of the Islamist party (Justice and Charity) among the peripheral constituency even though the Justice and Charity still maintains a strong following. PJD owes its relatively strong showing in legislative elections to the shift in the peripheral groups’ increasing prosperity and strength emanating from the economy’s semi-competitive nature in the post-liberalization period.

Given their various levels of liberalization, Turkey has the strongest MDP, Egypt has the weakest one, and Morocco is in between. Table 2 elaborates the strength and weakness of MDPs in these three cases in comparison to their Islamist alternatives.

Concluding Remarks

Being fully aware of the preliminary nature of the conclusions drawn here due to both the limited number of cases and an imperfect empirical analysis, I suggest that the analysis so far carries two major implications in conceptualizing the relationship between Islam and democracy, and how MDPs might prove to be the best option in having Islamist politics working with democracy. The first one is the importance of the creation of a competitive environment in society, especially in the economy. Most discussions on the liberalization of Middle Eastern economies underestimate the significance of the creation of competitive economies. In contrast, in many Middle Eastern countries the state elite have ensured their continued control over economy through the façade of liberalization. Competition and liberalization underlies the socioeconomic transformation in the society.

The second result is the strategic flexibility of Islamist political actors vis-à-vis changing economic conditions and the transformation of their societal allies. In a competitive economic and political environment, domestic groups, such as the Islamic political actors, are provided with an opportunity to contest the supremacy of the already-powerful center. The transformation of former Islamist politicians in Turkey, Egypt, and Morocco was not led by the innate character of Islam; instead, it was caused by socioeconomic factors.

Endnotes

- Vali Nasr, “The Rise of Muslim Democracy,” Journal of Democracy, Vol. 16, No. 2 (2005), pp. 13-27.

- For a similar discussion under the shift from political Islam to social Islam, see İhsan Dağı, “Turkey’s AKP in Power,”

Journal of Democracy, Vol. 19, No. 3 (July 2008), pp. 25-30. - Christian Democratic parties in Europe have similar policy positions. Ziya Öniş and Fuat Keyman, “A New Path Emerges,” Journal of Democracy, Vol. 14, No. 2 (2003).

- Jillian Schwedler, Faith in Moderation: Islamist Parties in Jordan and Yemen. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006); Michael J. Willis, “Morocco’s Islamists and the Legislative Elections of 2002: The Strange Case of the Party That Did Not Want to Win,” Mediterranean Politics, Vol. 9, No. 1 (2004) pp. 53-81; Murat Somer, “Moderate Islam and Secularist Opposition in Turkey: Implications for the World, Muslims and Secular Democracy,” Third World Quarterly, Vol. 28, No. 7 (2007), pp. 1271-1289; Carrie Rosefsky Wickham, “The Path to Moderation: Strategy and Learning in the Formation of Egypt’s Wasat Party,” Comparative Politics, Vol. 36, No. 2 (January 2004), pp. 205-228.

- Francesco Cavatorta, “Civil Society, Islamism and Democratisation: The Case of Morocco.” Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 44, No. 2 (2006), pp. 203-222.

- Ümit Cizre (ed.), Secular and Islamic Politics in Turkey: The Making of the Justice and Development Party, (New York: Routledge, 2009).

- Davut Ateş, “Economic Liberalization and Changes in Fundamentalism: The Case of Egypt,” Middle East Policy, Vol. 12 No. 4 (Winter 2005), pp. 133-144.

- Fareed Zakaria, “Islam, Democracy, and Constitutional Liberalism,” Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 119, No. 1 (2004), p. 16.

- Şerif Mardin, “Center-Periphery Relations: A Key to Turkish Politics?” Daedalus, Vol. 102, No. 1 (1973), pp. 169-190.

- See Ali Çarkoğlu, “The New Generation Pro-Islamists in Turkey: Bases of the Justice and Development Party in Changing Electoral Space,” Hakan Yavuz (ed.), The Emergence of a New Turkey: Democracy and the AK Parti (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2006), pp. 160-184.

- The conceptualization was introduced to analyze Turkish politics, yet I find it useful for the broader set of Muslim-majority countries in the Middle East since state-society relations and social cleavages are structured along the same lines in other countries as well. See Özbudun for a detailed analysis: Ergun Özbudun, “The Ottoman Legacy and The Middle East State Tradition,” L. Carl Brown (ed.), Imperial Legacy (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996), p. 134.

- Ben Ross Schneider, “Organizing Interests and Coalitions in the Politics of Market Reform in Latin America” World Politics, Vol. 56, No. 3 (April 2004), pp. 456-479; Erik Wibbels, “Dependency Revisited: International Markets, Business Cycles, Social Spending in the Developing World,” International Organization. Vol. 60, No. 2 (Spring 2006), pp. 433-468.

- Kiren Aziz Chaudry, “Economic Liberalization and the Lineages of Rentier State,” Comparative Politics, Vol. 27, No. 1 (1994), p. 4.

- See, for example, Layna Mosley’s study on international financial investors, Global Capital and National Governments (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

- Mohammed Ayoob, The Many Faces of Political Islam, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2008).

- See Somer, “Moderate Islam and Secularist Opposition in Turkey: Implications for the World, Muslims and Secular Democracy,” and Cizre, Secular and Islamic Politics in Turkey: The Making of the Justice and Development Party for the moderation of political Islam as a reaction to the center.

- The concept of crony liberalization is based on the more familiar term crony capitalism generally applied within the context of East Asian economies. See Peter Enderwick, “What’s Bad About Crony Capitalism,” Asian Business and Management, Vol. 4, No. 2 (June, 2005), pp. 117-132, and Stephen Haber (ed.), Crony Capitalism and Economic Growth in Latin America (2002).

- Enderwick, “What’s Bad About Crony Capitalism.”

- Tarik M. Yousef, “Development, Growth and Policy Reform in the Middle East and North Africa since 1950” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 18, No. 3 (Summer, 2004), p. 111.

- Turkey Statistical Institute, Türkiye’deki Küçük ve Orta Ölçekli İşletmeler dataset.

- Lobna M. Abdellatif and Ahmed Farouk Ghoneim, “Competition, Competition Policy and Economic Efficiency in Egypt,” Khalid Sekkat (ed.), Competition and Efficiency in the Arab World (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2008), pp.2 1-67.

- Lahcen Achy and Khalid Sekkat “Competition, Efficiency and Competition Policy in Morocco,” Khalid Sekkat (ed.), Competition and Efficiency in the Arab World (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2008), pp. 123-158.

- Adem Esen and M. Kemalettin Conkar, Orta Anadolu (Konya, Kayseri, Sivas ve Tokat) Girişimcilerinin Sosyo-Ekonomik Özellikleri, İşletmecilik Anlayışları ve Beklentileri Araştırması, (Konya: Konya Ticaret Odası, 1999); Ziya Öniş and Umut Tüurem, “Business, Globalization and Democracy: A Comparative Analysis of Four Turkish Business Associations,” Turkish Studies, Vol .2, No. 2, (2001); Ergun Özbudun and Fuat Keyman, “Cultural Globalization in Turkey,” Peter L. Berger and Samuel Huntington (eds.), Many Globalizations: Cultural Diversity in the Contemporary World (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002).