Turkey was ruled by coalition governments between 1991 and 2002. A major economic crisis and political turmoil in the late 1990s and early 2000s cost a king’s ransom to political parties in the Parliament and voters discarded these parties soon after. In the general elections of 2002, only two parties managed to enter the Parliament, the Justice and Development Party (AK Party) and the Republican People’s Party (CHP). The AK Party came to power alone and has won every single election in the last 13 years.

On the eve of the June 7, 2015 elections, the expectation was for an AK Party government. However, hopes failed with the announcement of the results. Although the AK Party won 40.87 percent of the votes, which is considered a success for parliamentary systems, it failed to reach a parliamentary majority to form a single-party government. On the morning of June 8, 2015, having had a long period of political stability, Turkey once again woke up to a government problem.

HDP’s June 7 Victory

A crucial outcome of the June 7 elections was that the AK Party lost power. On the other hand, another noteworthy result of the polls was that the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) overcame the 10 percent national election threshold and made it in to the Parliament. Previously to bypass the threshold, predecessors of HDP had entered elections with independent candidates, winning 22 seats in 2007 and 36 seats in 2011.

The co-leader of the HDP, Selahattin Demirtaş, speaks during an election rally on June 3, 2015, in Mardin. | AFP PHOTO / İLYAS AKENGİN

In 2015, HDP decided to join the race as a party –not through independent candidates. Considering that its voting percentage remained in between 6 and 7 percent in the previous parliamentary elections, this seemed extremely risky. Yet, the June 7 elections resulted in a victory for HDP. The party received more than six million votes (13.12 percent) and gained 80 seats in the Parliament. It has become the third party, leaving the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) behind in terms of the total number of parliamentary representatives.

HDP doubled both the number of votes and of deputies, and the leading factors behind this election success were: (i) As HDP joined forces with the anti-AK Party bloc, some groups who were reluctant towards HDP in the past, this time provided support with their “strategic votes” in order to curb a single-party government by the AK Party. (ii) HDP ran an election campaign with the slogan, “We will not let you become a President”, focusing on President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. (iii) HDP successfully worked on the promise that the Kurdish identity would be strongly represented in the Parliament if the party were to manage to enter the National Assembly, and if the awareness about Kurdish identity was raised. (iv) The mainstream media hitherto remaining aloof to HDP provided great support to the party for the June 7 election. (v) The motivation gained through the fact that HDP co-chair Selahattin Demirtaş had received almost 10 percent of the votes (9.76 percent) in the presidential race of 2014. (vi) Demirtaş’s political performance was regarded to be superior to that of other opposition leaders, namely Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu of the CHP and Devlet Bahçeli of the MHP in the run up to the election.

According to Kurdish constituents, politics would prevail once a considerably powerful HDP were to set foot in the Parliament, and then the outlawed PKK’s armed struggle against Turkey would end

The big increase in the HDP votes was not just because of the well-directed efforts, choices and work of the party, but because of the mistakes made by the AK Party in the same period. The AK Party’s mistakes played a critical role in HDP’s vote gain, such as: (i) Kurds in general were disturbed by some unfortunate statements made by the AK Party during its rivalry with HDP. For instance, the allegations against the HDP and PKK about promoting Zoroastrian belief did not only disturb the HDP’s social base, but also the broader Kurdish public. (ii) The AK Party turned its back on the reconciliation process, of which the party had argued that it was the architect. Especially President Erdoğan’s open disapproval of the ‘Dolmabahçe declaration’ between the AK Party and HDP members and his statement that there is no negotiation table disappointed Kurds for whom the peace process means a lot. (iii) The AK Party failed to read what the incidents in Syria, particularly in Kobani meant for Kurds, and brushed it aside. (iv) The majority of Kurds were convinced by HDP’s discourse, rating the AK Party with ISIL which has become Kurdish political identity’s constitutive other, and the AK Party failed to rebut the discourse. (v) The AK Party did not have a discourse and a candidate list to embrace the Kurdish issue and its solution prior to the June 7, 2015 elections.

Support for Democratic Politics

Each of the factors above weighed in some measure. However, the mainspring of HDP’s election victory beyond its expectations on June 7, 2015 was the Kurdish people’s demand for peace. On June 7, HDP won the support of Kurds living both in the East and the West of Turkey. Thanks to the on-going Reconciliation Process for the last two years, Kurds had realized that the settlement of the Kurdish issue would be possible through democratic politics, so they had high hopes. A strong representation of Kurds by HDP in the Parliament would reinforce politics and enable the transfer of control from armed entities to civilians. The Kurdish issue had to be disengaged from circles of violence and definitely had to be a matter of democratic politics. There had to be an end to deaths and the solution to the problem had to be found in the Parliament.

The election was over, but HDP could not leave the election atmosphere behind and continued with the conflict strategy against the AK Party

According to Kurdish constituents, politics would prevail once a considerably powerful HDP were to set foot in the Parliament, and then the outlawed PKK’s armed struggle against Turkey would end. HDP ran an election campaign accordingly on such prospects. HDP officials were claiming that if they managed to enter the Parliament as a political party, peace would be established and that the PKK would stop the armed struggle. They claimed that only a strong HDP could make the PKK come down from the mountains.

Voters did not leave HDP’s discourse unreturned. They supported it and strongly carried the party to the Parliament allowing them to gain a significant electoral success in the June elections. HDP, with independent candidates, received 5.3 (1.835.486 votes) and 6.6 (2.819.917) percent of the votes respectively in the 2007 and 2011 parliamentary elections. Therefore the party achieved a great increase in its votes, to 13.12 percent (6.054.865 votes), in the June elections. It was particularly successful in two points. Firstly, it successfully implemented the strategy of ‘becoming the only power which can stop the AK Party and Erdoğan’ so mobilizing the anti-Erdoğan camp. Secondly, it significantly limited the AK Party’s electoral success in the East and Southeast of Turkey and became the dominant party in the region. It gained seats in 26 cities, coming first in 14 cities and in the region, emerging as a strong new force in Turkish politics. A wide sphere of politics laid in front of HDP and considering the ineffectiveness of the other two opposition parties, it seemed that HDP had made a very good start. If the party were to advocate and strengthen democratic politics, it could expand grassroots support gained through the June 7 elections.

The Missed Opportunity

This historic opportunity, however, was missed due to reasons stemming from both HDP and PKK. The election was over, but HDP could not leave the election atmosphere behind and continued with the conflict strategy against the AK Party. In fact, as soon as the poll results were announced, HDP officials issued statements that they would not be a part of any cooperation with the AK Party. Remarks having no political or sociological grounds, such as the “anti-AK Party front” and “the 60 percent bloc” were accepted by HDP which was led by a policy line of “we might work with the MHP, but never with the AK Party.” HDP did not raise any objections even when the CHP chairman Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu offered Devlet Bahçeli (the leader of the MHP) the seat of the prime minister, in a deal which would have included the HDP in the government.

This was not an attitude reflecting the wish of the many who voted for HDP. Constituents voted for HDP not for it to be involved in political equations that were destined to fail, but to have it assume responsibility in the reconciliation process and advocate democratic politics.

The real move that left HDP in a difficult position was made by the PKK. As a matter of fact, it is possible to say that Qandil was caught off-guard by the June 7 election results. Since HDP came out of the elections strong and gained 80 seats in the Parliament; the results clearly meant that people preferred politics over weapons and wished the armed struggle to stop. However, it was also clear that the PKK was not ready for this and it could not bring itself to accept the new reality that now politics would run the show.

PKK’s Strategy of Conflict

The PKK prevented HDP from transforming itself into a real political actor by acting differently in two ways. First of all, the PKK humiliated HDP at every chance it had after the June 7 elections. PKK leaders in Qandil disclaimed each statement issued by HDP officials. For instance, Demirtaş said, “We will honour our responsibility towards the lent votes” when he was expressing gratitude to non-HDP electors who had voted for his party [on June 7]. Qandil immediately responded: Mustafa Karasu stated that “There are no lent votes. HDP officials misevaluate the situation. … I do not know where this came from. Some people might have voted for the HDP for it to pass the threshold. This does not mean they are lent votes. It should not be called lent votes.” As HDP officials, such as the party co-president Selahattin Demirtaş and MP Sırrı Süreyya Önder stated: “We cannot get into a partnership with the AK Party under any circumstances”, Qandil rebuffed them with Murat Karayılan’s response: “These are childish acts. The election was held and a new balance has emerged. HDP should adopt a position according to this new balance.” HDP accordingly followed the PKK’s lead as party co-president Figen Yüksekdağ said “We are open to all the proposals and negotiations about taking part in the government or forming a coalition government.” But this time Duran Kalkan from Qandil contradicted her when he tweaked: “To join in power means to become a party of the order. You cannot join in with the power.”1 In short, every single political move by HDP was discredited by PKK, warning HDP not to step out of line and know its limits, and affirming once again itself to be the real decision-maker.

Secondly, PKK has returned to violence. Shortly after the elections, it announced that the ceasefire was over, and increased kidnappings, waylays and arsons. Bese Hozat, one of the PKK leaders, declared they were waging the “revolutionist people’s war.” Cemil Bayık, another leader of the organization, called people to arms. The PKK held the State responsible for the bomb attack committed by ISIL in the town of Suruç, Şanlıurfa, and targeted soldiers and police officers. The State, in retaliation, launched a massive operation against PKK camps both in and out of the country. In the aftermath of the Suruç bombing, hot encounters took place. The state showered the PKK targets with bombs inside and outside of the border. The PKK responded in two ways: carried the battle into cities by digging trenches in the streets, and declaring what it calls ‘democratic self-government’; therefore, trying to create a de facto situation. Thereupon, Turkey entered a period of direct engagement with the PKK starting on July 24, 2015.

The sphere of politics narrowed when violence took the stage and the Reconciliation Process was put “in deep-freeze” as President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan declared. The PKK rushed into apply its strategy of conflict although this was obviously wrong. In these circumstances there was a risk that HDP had to take while all eyes were on the party. HDP should have decisively voiced the opinion that sticking to the strategy of conflict was a terrible mistake and stood up against it. Unfortunately, they could not do this and failed to show the will to own the sphere of politics.

The Cost of Violence

After June 7, 2015, it seemed that Turkey was to face a new “period of coalitions”. However the anti-AK Party opposition could not find common ground, either among themselves or with the AK Party, to form a coalition within the legislated time-frame. Therefore the AK Party, having lost the power by a narrow margin, wanted to try one more time and Turkey headed to the polls once again, as mandated by the Constitution. Violence escalated and political limbo and security concerns made a peak during the five months from June 7 to November 1. Therefore the November 1 election would be revealing as to how people responded to balances that had changed since June 7.

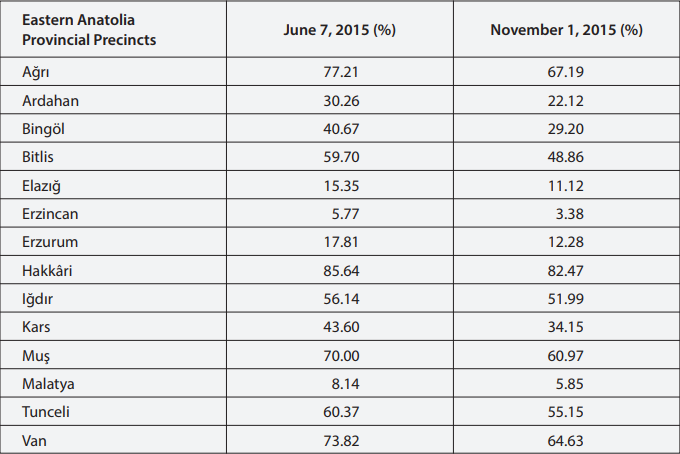

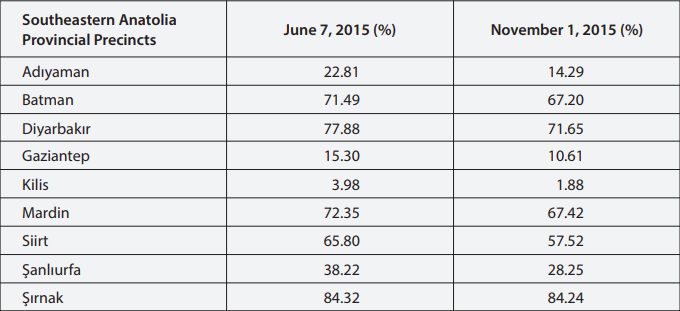

People showed that they wish to have stability and security in the country by increasing the vote for the AK Party, and expressed discontent for violence and conflict by decreasing the vote for HDP on November 1. In the repeated elections: (i) HDP lost one million votes. (ii) HDP lost 21 seats in the Parliament, and the number of HDP deputies dropped from 80 to 59. The party lost parliamentary seats in many provinces. The number of HDP parliamentary representatives decreased from 10 to nine in Diyarbakır; from five to three in Şanlıurfa; five to four in Mardin; seven to six in Van; four to three in Ağrı; eleven to seven in İstanbul. HDP suffered losses in deputy seats in the provinces of Adana, Mersin, Gaziantep, Iğdır, Kars and Tunceli (from two in each, to one). In the June 7 election, HDP had gained one seat each in Antalya, Ardahan, Bursa, Erzincan, Erzurum and Kocaeli; but lost all of them in these provinces on November 1, 2015. (iii) HDP’s vote decreased nationwide from 13.12 percent to 10.75 percent. HDP particularly suffered serious losses in the Southeastern and Eastern Anatolia provincial precincts.

Due to the decrease in vote in November, HDP lost the psychological upper-hand in these two regions which they had gained after June 7. In the large cities in western Turkey, where it had gained deputy seats on June 7, HDP experienced vote shrink on November 1, 2015.

Concentrating on Self-Critique

Following the November 1 elections, HDP co-chairs tried to explain the reasons behind the change in their votes, making no self-criticism and concentrating only on finding a scapegoat. According to them; AKP’s pressure on HDP by using all instruments of the state, bombings allegedly targeting HDP and their supporters, and their not being able to have a single election rally were the primary factors affecting the November 1 results. However, it would be more accurate to interpret HDP’s loss of votes through the choices they made rather than on external factors. In this regard, the policies HDP followed during the election and the reconciliation processes must be the first thing to discuss.

The tables above indicate that hot encounters were not in favor of HDP. PKK attempted to transfer its experiences in Syria to Turkey, dug trenches in cities and towns administered by HDP-member mayors, and tried to create “liberated-zones.” The organization planned to create de facto control by means of declarations of self-government and build PKK-controlled regions out of reach of the State authority. However, such acts of by the PKK disturbed a significant number of voters who had supported HDP on June 7 for the sake of reconciliation. The same voters were not happy with HDP’s attitude either. The control of HDP by PKK violence caused these electors to question their choices. The voters’ will for democratic politics, ought to be noticed. For this reason, both the HDP and PKK must admit that they lost because of violence and a lack of self-criticism, rather than concentrating on external factors to blame for the vote loss. They would be wise to come up with alternative policies in order to find a way out of this situation.

Discussions naturally focused on HDP’s losses as the party experienced a decrease in its vote by 15 percent in five months. However, there is a point that should not be overlooked. The mainstream Kurdish politics, represented by HDP today, had received only five to seven percent of votes in the elections that they had participated in from 1991 to 2015, via independent candidates and different parties. The vote rate rose to 13 percent on June 7, but dropped to 10 percent on November 1, 2015. In other words, although HDP lost three points on November 1 of the six points it had gained on June 7, it has still managed to gain three points (over its mainstream vote).

Both the HDP and PKK must admit that they lost because of violence and a lack of self-criticism, rather than concentrating on external factors to blame for the vote loss

It was extremely important and valuable that HDP overcame the (10 percent) national election threshold despite the vote loss. Voters have warned HDP, but kept it above the threshold; therefore showing that they wish HDP to settle the Kurdish issue by using political mechanisms. In this context, HDP can perform a crucial task. Kurds gave a message on November 1 that they are for democratic politics, and took side with keeping political channels open. If HDP reads this message accurately and adopts a policy to value its political presence rather than violence, it will be a great benefit both for itself and Turkey. Therefore the more such a line of politics transforms HDP into a real and significant actor, the more it will contribute to the most urgent problem of Turkey today, the settlement of the Kurdish issue through the Parliament.

Endnote

- Retrieved January 11, 2016 from http://www.

haberler.com/hdp-ve-kandil-den-celiskili-aciklamalar- 7426450-haberi/.