Introduction 1

The study of the strategic culture within the Cold War. Cultural approaches to strategic studies. Discussion, however, has also started. Security organizations are of intergovernmental character, and decisions taken by them. Therefore, we can assume that if organizations have different members, structures and capacities, they also have different strategic cultures.2 Cultures are therefore based on different ideas, perceptions and beliefs, and thus are socially constructed by collective understanding and interpretation about the world. 3 The study of strategic culture of these organizations then plays a key role.

The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) which perceive each other as threats, and which prefer deterrence and non-cooperative approaches. This is a typical feature of the OSCE at the beginning of the 21 st century. 4

The crisis in Ukraine, nevertheless, proved that the OSCE was the only security organization in Eastern Ukraine. We have chosen the crisis in Ukraine, which is the largest conflict in the European area in which the Russian and Western interests clash, and Russia has denied some of the core principles of the OSCE. OSCE). Recent research into the OSCE 5However, the case of Ukraine shows that it is activated in an escalated case, such as one in Ukraine, where at least partial cooperation among among enemies ”is happening in a non-cooperative context. In addition, the OSCE may also have played its role. This could explain the paradox in which the organization reacts based on certain principles, in the case of the conflict analyzed here, clearly dysfunctional.

The first aim of the study is to identify the specific features of the OSCE as a regional security governance framework between 'non-allies', based on discourse analysis of the texts. The results provide a framework for the case study. The second objective is to test this strategic culture in the case of Ukraine. strategic culture were reflected in the OSCE actions.

The Strategic Culture of the OSCE

The discussion about strategic culture has been linked to the cultural and sociological turn in the human sciences.6 It is, therefore, evident that international reality is not merely the result of material and physical forces, but it is a phenomenon socially constructed through discourse power.7 Strategic culture has a significant impact on the norms and values of organizations and their institutionalization.8 Social constructivists also stress that interests are not pre-given, but they are subject to redefinition and change as a reaction to the changing constitution between states and norms as threats are the product of inter-subjective dynamics and do not necessarily exist ‘out there.’9

The crisis in Ukraine, nevertheless, proved that the OSCE was the only security organization, which directly participated in the effort to de-escalate, stabilize and search for a solution to the conflict in Eastern Ukraine

The term “strategic culture” traditionally refers to military force and the rules governing its use. Johnston for instance defines strategic culture as an integrated system of symbols (e.g. argumentation structures, languages, analogies, metaphors),10 which acts to establish a pervasive and long-lasting strategic preference by formulating concepts of the role and efficiency of military force. Johnston recommends starting at the very beginning of strategic culture and moving systematically forward through the analysis of its formative age. When studying strategic culture, Johnston admits that it may include a wide range of material from various texts concerning the development of an understanding of war and peace. Johnston solves this problem by using the methods of symbol analysis and cognitive mapping.11 Although the original strategic culture was drawn exclusively to military power and its use,12 later military force was understood as only one of the tools to achieve policy goals.13 Strategic culture is generally understood as a set of norms or values or principles related to the understanding of security.14 Colin Gray understands the strategic culture more comprehensively as a set of ideas, positions, traditions and behavior, which result in the interaction of strategic culture in institutions and in procedures.15 Regardless of the individual approaches to strategic culture, it is evident that it does not concern decisions about actual implementation of aims, means and ways, but rather contains a set of priorities and preferences regarding the given policy.16

This approach makes it possible to assign a strategic culture to an actor such as an international organization. There are nevertheless fundamental differences when we study the strategic culture of an international organization and the strategic culture of states. First, as Acharya points out, the strategic culture of states dominantly focuses on “the maintenance or management of an adversarial relationship. The concept is not usually applied to issues of conflict resolution, institution building, and cooperation…”17 The emphasis on the ability to cooperate is therefore of fundamental importance in the case of identification of features of strategic culture. Second, we can assume that in the study of the culture of organizations we focus on regional security and regional security links, i.e. we take into account “collective strategic behavior, or ‘habits of thought’ of regional institutions with regard to security affairs.”18 These two fundamental differences may also be reflected in the case of identification of the strategic culture of the OSCE and its features.

Strategic culture could be seen in relation to the institutional culture as its specific subset used for actors dealing with security

Strategic culture may perform the function of a certain limitation for strategic elites, which do not choose from all strategic options in their decision making, but only from those which they perceive as acceptable with regard to their strategic culture. Therefore, strategic culture limits the strategic elites in the selection of individual strategic options. Because states enter into international organizations, we can claim that they can subsequently create and share a strategic culture of such organizations in addition to their own strategic culture. Such a situation creates conditions for transfer of interest in strategic culture to international organizations. The strategic culture of each state and international organization thus issues from its historic experience and political structure, always reflecting its past experience as well as specific contemporary political intentions. Decision makers gradually adopt traditional, long-term strategic approaches and procedures. At the same time, they also significantly influence these approaches in specific situations.19

The emphasis on security in all its forms, including the approach to the use of force, differentiates the term strategic culture from the term institutional culture. The term institutional culture is in general related also to institutions (not only international organizations) in relation to their values, and it operates with institutional logic in a social context. It also allocates it certain features,20 and in general it emphasizes primarily the habits, skills and styles of actors concerning how they interact, and how they negotiate and construct strategies of action21 without links to security. Therefore, we can conclude that strategic culture could be seen in relation to the institutional culture as its specific subset used for actors dealing with security.

In the case of the OSCE we can in general expect “the vision of a free, democratic, common and indivisible Euro-Atlantic and Eurasian security community stretching from Vancouver to Vladivostok, rooted in agreed principles, shared commitments and common goals.”22 Three terms related to security are reflected in the OSCE: (i) comprehensive security (i.e. a complex link of classical military security with its economic, environmental and human factors which are not only considered interlinked by the OSCE, but also equally important), (ii) indivisible security (i.e. understanding that security of one OSCE participant state cannot be detached from the security of other states in the region, which is actually an expression of security solidarity), (iii) and cooperative security (i.e. security based on elementary trust and cooperation, peaceful resolution of disputes and operation of mutually cooperating multilateral institutions).2

When examining the strategic culture of the OSCE we shall more closely focus on the analysis of the OSCE’s understanding of security and its approach to security threats and their elimination. Special emphasis should be put on the assessment of whether the OSCE prefers coercive or persuasive strategies, i.e. whether the OSCE prefers military or soft power tools. To understand the strategic culture of the OSCE, the article first examines the reflection of the strategic culture of the OSCE in its fundamental documents adopted by the OSCE since the origin of the Conference for Security and Cooperation (CSCE), the predecessor of the OSCE. Simultaneously it is necessary to identify the features of this culture.

The strategic culture of the OSCE issues from shared values which are an integral part of its official documents and which are reflected in the OSCE decision making procedures and activities of the organization. This culture is constructed and defining features based on discourse analysis of the main OSCE documents could identify it. Discourse analysis is a qualitative method developed by social constructivism, and it is most commonly linked either with language structure of a message or text, or with a rhetorical or augmentative organization of text or speech.24 Discourse analysis is considered an umbrella methodology, which can combine various methods;25 we specifically combine two approaches to discourse analysis: topical analysis, which enables identification of the basic framework for analysis26 and methods of critical discourse analysis. Fairclough analytically divides critical discourse analysis into three individual but mutually connected methods: description, interpretation and explanation, which reflect the three-dimensional approach to discourse.27

Identification of the Features of the Strategic Culture of the OSCE

When choosing the corpus of documents, we first have to define the criteria of selection of documents that will be analyzed. We also have to define the time framework for document selection. This enables us in the second stage to analyze the corpus of documents that contain texts that enable us to identify the strategic culture of the OSCE. The time framework of documents is rather wide, and covers the years from 1974 to 2015, which enables us to take into consideration a wider social and historical context, while we also take into consideration that it is necessary to include the documents of the CSCE (as the predecessor of the OSCE) into the analysis. The Helsinki Process, which started in the 1970s via the organization of the CSCE in Europe, was a rather unique and innovative phenomenon of European politics.28 The process of the follow-up meetings proved not only to be able to capture the dynamic development in the politico-military area in the second half of the 1970s and in the 1980s, but it also contributed to the transformation of the regional system at the end of the 1980s and in the 1990s.

We first evaluate the key documents of the organization that represents the official communication means and in general deal with the approach of the organization to security. These documents were adopted by the main political body, its summits. The norms, standards and values reflected in these documents are so comprehensive and serious that they are being called the OSCE ‘acquis.’29 The most significant documents in creating the political standards of the CSCE/OSCE included the Helsinki Final Act of the CSCE of 1975 (in particular the Helsinki Decalogue), the Charter for a New Europe of Paris 1990, the Charter for European Security of 1999 and the 2010 Astana Commemorative Declaration.

We also included the texts focusing directly and specifically on the political and military areas in the document corpus that relate to arms control measures, measures aimed at confidence building, and security and security sector management. These include in particular the OSCE Code of Conduct on Politico-Military Aspects of Security of 1994,30 The Vienna Document 2011 of the Negotiations on Confidence and Security-Building Measures (the document increased the transparency and predictability of behavior of the individual OSCE participants),31 the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe of 1990 (as an example of the process of arms control, disarmament and security and confidence-building measures within the OSCE territory) and the Treaty on Open Skies of 1992. The last two documents are legally binding agreements adopted by all participating states, but with the OSCE acting as a functional ‘umbrella’ of the treaties. Its regime cannot be considered a full-scale OSCE regime; however, it enables the OSCE to at least symbolically participate in the agenda of ‘hard’ security.32 Although the documents relating to the arms control measures are currently in crisis due to the tensions between Russia and the West, and have shown limited functionality, they are of fundamental importance for the identification of the strategic culture of the OSCE.

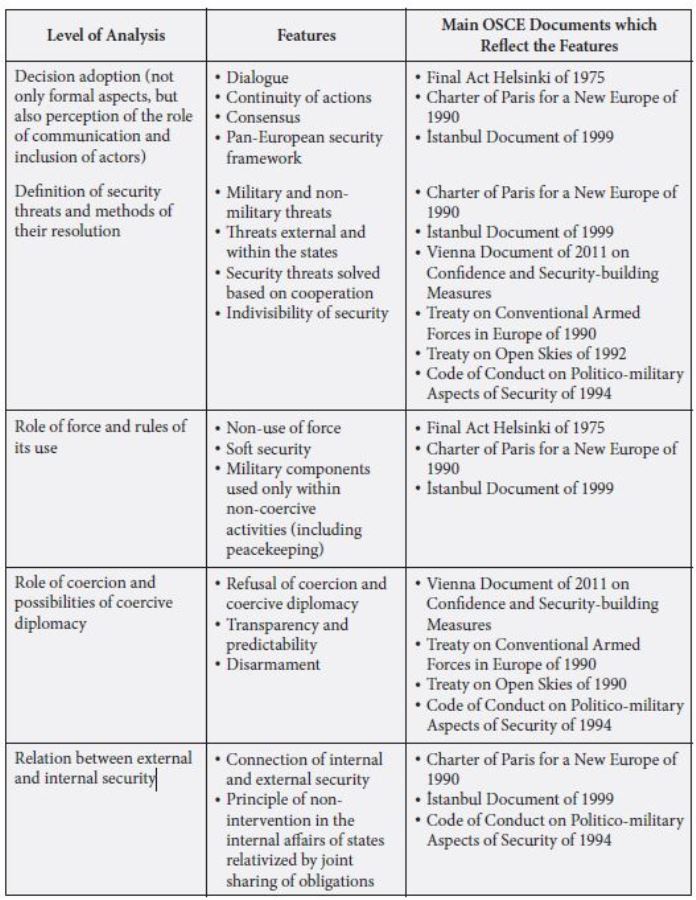

We have analyzed the context by examining selected documents, focusing on the keywords “security,” “threat,” “security challenges,” “force,” “disarmament,” “conflict,” “disputes,” and “resolution.” Afterwards, we identified the features of strategic culture which are respected and which frame the activation of the OSCE in the case of conflict resolution, and which define how the organization reacts. We analyze in particular the OSCE approach to security at various levels to provide a more complex approach to security and methods to analyze the reaction to security threats: (i) the method of adoption of decisions in security areas (not only formal aspects, but also the perception of the role of communication and participation of the individual actors); (ii) a definition of security threats and methods of their resolution; (iii) the role of force and rules of its use; (iv) the role of coercion and the possible use of coercive diplomacy; and (v) the relation between external and internal security. Inclusion of these levels enabled connection of formal and contextual analysis of the culture of reaction of the monitored organization.

The results are summarized in the following table, which also shows in which documents the given features can be found. The individual features are complementary and can also be considered in some respects overlapping; however, they are based on monitoring the different levels of analysis:

Identifications of Features of the Strategic Culture of the OSCE

At the first level, we demonstrated that the formal aspects of the decision –all decisions require a consensus– not only demonstrate the principle of equality, but also reflect respect for the key role of the necessity to lead a dialogue and respect the pan-European vision of security. The OSCE participant states understand the OSCE as a special case of an institutionalized continuous security dialogue and cooperation. Continuous dialogue is of fundamental importance for the constitution of the features of the strategic culture of the OSCE. The OSCE can thus be understood as a unique framework for a continuous cooperative security dialogue.33 This unique framework for multilateral communication simultaneously offers several different communication levels of states.34

The formal aspects of the decision not only demonstrate the principle of equality, but also reflect respect for the key role of the necessity to lead a dialogue and respect the pan-European vision of security

The OSCE also acts as a center for exchange of information among its participants to secure up-to-date information about security development (in particular in the Permanent Council in Vienna). A specific ‘culture of dialogue’ can be considered a value in itself, regardless of its materialized output.35 This may lead to a situation when the dialogue within the OSCE is less formal and more open (for its participants, not for the public), in particular as it does not need to be aimed at the negotiating of specific outcomes.36 The complex multilateral diplomacy under the auspices of the OSCE, in addition to the official OSCE dialogue, includes any meeting of diplomats within the official diplomacy or meetings of experts and officials within non-official diplomacy.37 The features of dialogue are of fundamental importance for the creation of the strategic culture of the OSCE as it calls for consensus in all OSCE decisions.38 It understands that states may modify the negative conditions of anarchy and may to a certain extent integrate their interests even in the pan-European security area. The OSCE can thus be understood as a key for pan-European security, while recognizing that there remain different, clearly articulated and cooperating power and decision making centers.39

It is also supported by the emphasis on a privileged partnership with the UN, since the OSCE is a regional agreement according to Chapter VIII of the UN Charter.40 The documents paradoxically take into account the fact that part of the strategic culture of the OSCE is the ability to use dialogue as a part of the solution of security also with the actor that is potentially or in fact the actor which breaches the security. This enables the adoption of certain decisions despite the existence of a consensus. The OSCE’s security and strategic culture is reflected in its institutional behavior (depending on the rule of consensus), in particular in the Permanent Council and the Forum for Security Cooperation.

The second level of analysis defined threats and reactions to the threats. Security threats are of military and non-military character. They are linked with the individual dimensions of the OSCE in which the political and military dimensions are significantly accompanied by the economic and environmental dimensions and by the human rights dimension. Special emphasis is put on the issue of minorities. Threats, whether of military or non-military character, should nevertheless be solved jointly. It is a manifestation of emphasis on cooperation and non-violent conflict resolution within the OSCE territory. Security threats of military or non-military character should ideally be solved by cooperation within the OSCE. Therefore, we can understand the OSCE as a security organization sui generis that stresses the so-called ‘soft’ security.41

States not only renounce the use of force in their mutual relations, but they also renounce the use of force in the case of a breach of the OSCE principles. This also applies to the origin of a violent conflict. This naturally limits the OSCE in the case of unwillingness of the participating states to resolve the conflict by cooperation. Should this cooperation not be possible, or should the states not be willing to cooperate, the OSCE is blocked. If security threats are solved exclusively by cooperation, a paradoxical situation occurs within the heterogeneous OSCE community in which the threats are being solved also by the actors who are the threats’ initiators. All security threats are thus to be solved by cooperation among the OSCE participating states. The İstanbul Charter of 1999 states: “Reflecting our spirit of solidarity and partnership, we will also enhance our political dialogue in order to offer assistance to participating States, thereby ensuring compliance with OSCE commitments… The only acceptable method of threat solution by cooperation is closely related to another feature, i.e. to the indivisibility of security.”42 The OSCE’s strategic culture assumes that states must cooperate together because their security is interconnected. It is manifested in the İstanbul Charter: “The security of each participating State is inseparably linked to that of all others. We will address the human, economic, political and military dimensions of security as an integral whole.”43

The conflict in Ukraine represents an important test for the functionality of the strategic culture of the OSCE in cases when violent conflict has already occurred in OSCE territory

The third level of analysis focused on the role of force and the rules of its use within the OSCE. The OSCE strictly excludes the use of force or deterrence in case of a conflict resolution. In other words, it denies the use of force as such. The İstanbul Charter of 1999 expected the sending of peacekeeping missions under OSCE management as a specific and limited situation.44 The OSCE thus does not dispose of deterrence tools and the logic of the organization expects that security issues from its positive understanding. The security and strategic culture of the OSCE is in its essence non-aggressive, and it can be even understood as a certain doctrine of non-escalation. The use of military force is accepted only if it consists of non-coercive activities, in particular in the framework of assistance and monitoring.

The fourth level of analysis discussed the role of coercion and possible coercive diplomacy. The documents again refuse these options. The emphasis is therefore put on measures that lead to the building of confidence and security, as well as finding a political basis for arms reduction, which requires greater transparency and predictability in the field of military security. The OSCE deals with questions related to military force, but from the perspective of their regulation, with respect to their size and possible use. This culture thus excludes coercive methods, and its characteristic features include dialogue rather than confrontation, cooperation rather than deterrence, transparency rather than classification. It also stresses prevention and the common interests of the OSCE participating states even if there is a crisis situation. Gross violation of such obligations may therefore not be seen as a reason for imposition of sanctions. Trust in good will and good intention and full cooperation can be considered a certain weakness of the entire approach.45 Transparency is understood as an important precondition for the building of a secure environment. The İstanbul Charter of 1999 states that the relations will be built in conformity with the concept of common and comprehensive security, guided by equal partnership, solidarity and transparency.46

The last significant level of analysis focused on the interaction between internal and external security. A specific feature of the strategic culture of the OSCE also includes a new approach to security that is not understood purely as a concept of external security, and therefore it may also be applied to a solution of internal problems as it connects security with political and human dimensions. Security threats issue in particular from interstate conflicts. The OSCE deals mostly with conflicts related to minority questions. The OSCE documents on the one hand fully recognize the sovereignty of the individual participating states and the principle of non-intervention into internal matters of states; however, on the other hand, the OSCE documents do not clearly differentiate whether the threats are of an external or internal character. This may be justified by full recognition of the principle of indivisibility of security. The İstanbul Charter states that “it has become more obvious that threats to our security can stem from conflicts within States as well as from conflicts between States… Security and peace must be enhanced through an approach which combines two basic elements, we must build confidence among people within States and strengthen co-operation between States…”47 Interstate conflicts are thus not understood only as a breach of the OSCE principles, but also as a threat for other participating states and for the entire OSCE territory.

Attempts to De-escalate the Conflict in Ukraine and Reflections

of the Strategic Culture of the OSCE

The conflict in Ukraine represents an important test for the functionality of the strategic culture of the OSCE in cases when violent conflict has already occurred in OSCE territory. A significant feature of the conflict also included the fact that the participating states declared their policies towards each other as threats in the context of the Ukraine crisis. The fact is that Ukraine and most of the OSCE participant states perceive Russia as the aggressor.48 The OSCE, nevertheless, became a platform for conflict mitigation and the search for a solution. The OSCE thus found itself in a very critical situation with regard to its strategic culture, which was not ‘ready’ to enter into a violent conflict. There was, however, at least a general understanding that the crisis in Ukraine must be solved only in minimally symbolically cooperation at the pan-European level. Attempts to engage the EU in the solution proved impossible, so it was finally agreed that Russia would also be involved in the solution, and the OSCE was a unique opportunity. The EU has become an important supporter of the OSCE activities.49 The OSCE also had previous experience with the OSCE monitoring mission in Crimea in 1994-199850 and implementation of the Recommendations of the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities,51 so it was well aware of the background of the contemporary crisis in Ukraine.

The OSCE was not activated until the Spring of 2014 in connection with destabilization and the outbreak of violent conflict in Eastern Ukraine. The OSCE activation thus occurred not only thanks to the participating states, but also due to the ‘quick moving Vienna bureaucracy.’52 The Conþict Prevention Centre within the OSCE Secretariat contributed to a smooth exchange of information and participation of experts in regional conflicts.53

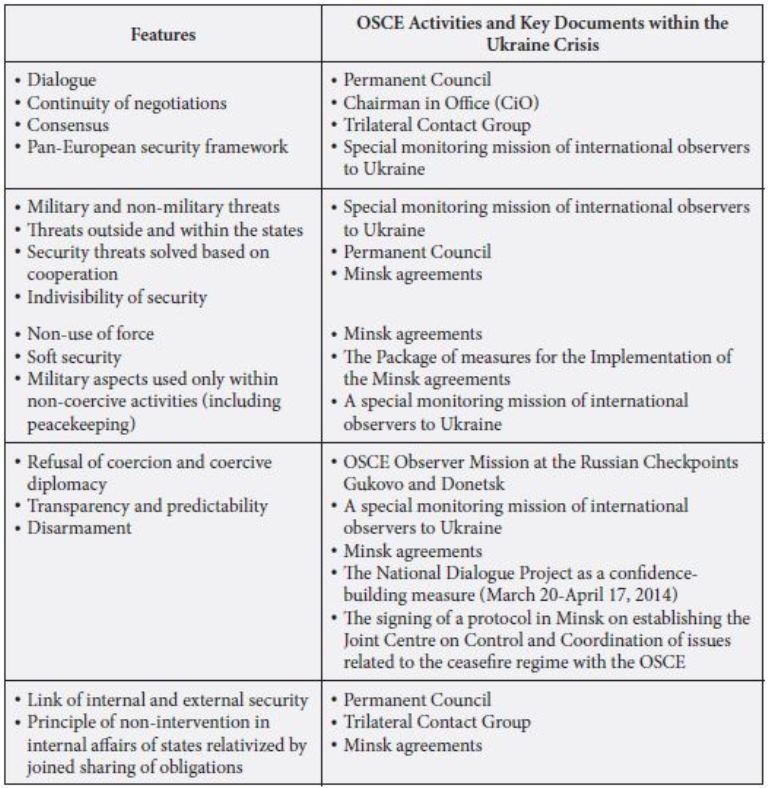

When focusing on the analysis of the OCSE in the crisis in Ukraine, we focused not only on the texts which were adopted within the OSCE and which mostly represented decisions on the individual operation activities of the OSCE, but also on the activities of the OSCE themselves. We expect that the specified features must have been reflected in the character of these activities and they must have defined the reaction of the OSCE itself. The following table summarizes how the individual features were demonstrated in the activities of the OSCE bodies.

Strategic Culture of the OSCE within the Crisis in Ukraine

The first feature, which connects the role of dialogue and consensus with the Pan-European understanding, has not been reflected only in the interstate bodies of the OSCE (namely in the Permanent Council), but also in a consensus based on intergovernmental logic. The role of the OSCE Chairmanship (Chairman in Office, CiO) has proved to be crucial. The Swiss Presidency played a key role in 2014,54 and Switzerland has regularly and actively opened the question of Ukraine since the very beginning of its CiO, and has appointed an OSCE Chairperson proxy for Ukraine.55 OSCE is a fragmented organization, composed of a Secretariat managed by a Secretary General, who is not independent of but subordinated to the Chairmanship.56 Discussions on the crisis were held primarily in the Permanent Council, which meets weekly and thus enables an immediate acquisition of information and exchange of opinions.57 Lefebvre states that:

in spite of the difficulties of consensus-based decision making, it is not impossible to agree on declarations and decisions within the Organization… In early 2015, thanks to the work of the Serbian Chairmanship, the Permanent Council adopted two declarations, one on Ukraine calling for de-escalation (whereas the previous Basel Ministerial Meeting had been unable to agree on a political statement on Ukraine) and another (prepared by France) after the Paris attacks…58

The rapid approval and deployment of the mission allowed for the ideal constellation given by the CiO, the secretariat and some participating states.59

The OSCE thus proved that in critical situations in the European context it was activated as a unique forum for inclusive dialogue and as a tool for international engagement. The Ukraine crisis escalated in March 2014 in Eastern Ukraine. The ability to maintain dialogue within the OSCE may seem of fundamental importance, and it is also emphasized by some scholars. Kropatscheva stresses that:

it is important to note that amidst the acute worsening of Russian-Western and Russian-Ukrainian relations, while the hostile rhetoric was growing, while most other cooperation forms and communication channels had been suspended and sanctions were being imposed, it was in the framework of the OSCE that the first cooperative agreements, even those requiring consensus, as with the OSCE special monitoring mission of international observers to Ukraine (SMM), were reached.60

The participants have been able to achieve the first difficult compromises, which became possible because there were practically no other communication channels between Russia and the West, and because of the OSCE’s inclusive character. Lefebvre similarly states that “the OSCE not only brought an international presence to the Ukraine crisis, but it also soon became the main diplomatic channel for discussing and settling the conflict. This is due to the fact that no other international organization was properly designed to take over that role.”61

The OSCE proved that in critical situations in the European context it was activated as a unique forum for inclusive dialogue and as a tool for international engagement

Like other international organizations, the OSCE was unable to prevent the escalation of the conflict into war and the annexation of the Crimea. At least it was possible to use the deployment of an OSCE long-term instrument –the sending of a long-term mission. In Ukraine, the Project Coordinator has already been active, and participating states quickly agreed to send a Special Observer Mission and an observer mission to the Russian-Ukrainian border. The ability of dialogue and search for a common solution within conflict de-escalation even among potential enemies was finally confirmed by the adoption of a mandate of a long-term mission of the OSCE. The decision on deployment of an OSCE special monitoring mission of international observers to Ukraine was adopted at the 911th Plenary Meeting by a consensus decision on March 21, 2014, fully in the line with the strategic culture of the OSCE. It was approved on a request by Ukraine. Ukraine regarded in the interpretive statement the decision “as an emergency response of the Organization to the grave conflict around the Autonomous Republic of Crimea that stemmed from military aggression by the Russian Federation aimed at annexing this integral part of Ukraine’s territory.”62 These actions were considered illegal and violated imperative norms of international law (the Helsinki Final Act and agreements, which guarantee Ukraine’s territorial integrity, inviolability of borders and non-intervention in internal affairs of Ukraine). On the other hand, Russia in the interpretive statement noted that the Russian Federation proceeds from the assumption that the geographical area of deployment and activities of the mission are geographically limited as a result of the fact that the Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol has become an integral part of the Russian Federation.63 Even the strictly divergent opinions did not prevent dialogue, and the consensus decisions allowed the presence of the international community in the conflict.

OSCE observers near the village of Petrovskoye where the Ukrainian Government and the Donetsk People’s Republic complete the withdrawal of troops according to an agreement on disengaging the warring parties in the Donbass region signed on September 21, 2016. MIKHAIL SOKOLOV / Getty Images

OSCE observers near the village of Petrovskoye where the Ukrainian Government and the Donetsk People’s Republic complete the withdrawal of troops according to an agreement on disengaging the warring parties in the Donbass region signed on September 21, 2016. MIKHAIL SOKOLOV / Getty Images

The mission was established for “monitoring of the ongoing conflict between the Ukrainian army and separatist forces impartially, monitoring compliance with the Minsk II Agreement, and being the eyes and ears of the international community.”64 The aim of the unarmed civil mission is “to reduce tensions and fostering peace, stability and security; and to monitoring and supporting the implementation of all OSCE principles and commitments.”65 The mission is operating under the principles of impartiality and transparency with tasks including, among others, to “facilitate the dialogue on the ground in order to reduce tensions and promote normalization of the situation.”66 Some of these measures were supported by the OSCE Project Coordinator as the permanent OSCE field presence in Ukraine since 1999. This was enabled regardless of disagreements not only between Russia and Ukraine on the status of Crimea, but also among other states. The SMM has thus become the most visible engagement of the international community in the Ukraine crisis. Operational activities of the OSCE have demonstrated the inability to use military force with respect to its mandate. They have been so far understood as fully civilian and unarmed, putting emphasis on transparency and predictability and disarmament (in particular demilitarization of the buffer zone). Cooperation is expected also at the place of the mission operation and it is the basic limitation for the success or failure of its activities; the mandate of the mission does not take into account any coercion options. The inability to use at least lightly armed observers within the monitoring (they are in the area of every day breach of the ceasefire) is probably the most interesting feature of the OSCE activities, and to a certain extent it confirms the strategic culture of the OSCE.

Although the Minsk process has so far been unsuccessful in addressing the conflict’s resolution, the conflict in the east of Ukraine has been at least partly frozen and the international community has been included in the search for a way to de-escalate the conflict

As the conflict occurred directly at the borders of Russia, it was evident that it would be at least formally necessary to increase the transparency of the Russian-Ukrainian border. On July 14, 2014, the Permanent Council decided to deploy, without delay, OSCE observers to the two Russian border checkpoints of Donetsk and Gukovo on the Russian-Ukrainian border. The task was to monitor and report on the situation at the checkpoints of Donetsk and Gukovo, as well as on the movements across the border. The civil unarmed mission again operates under the principles of impartiality and transparency.67

The CiO was also represented in the Trilateral Contact Group that also includes Ukraine and Russia. The group was established in June 2014 to facilitate dialogue and resolution of conflict in Eastern Ukraine. Representatives of two unrecognized separatist republics also attended these meetings. Thus, not only states and representatives of the international organization, but also two non-state actors (“pseudostates”) were involved in the negotiations.68

The activities of the OSCE at least enabled the international community to enter into the “seemingly” internal conflict, which confirmed that the general principle of non-intervention in internal affairs of states is relativized by joint sharing of obligations in the case of a drastic breach of the OSCE acquis

The OSCE played a major symbolic mediation role in the negotiations between Russia and Ukraine within the crisis, and it became an important guarantor of the Minsk agreements. Similarly, the talks that led to the Minsk II deal were overseen by the OSCE. The Package of Measures for the Implementation of the Minsk agreements in 2015 ensures effective monitoring and verification of the ceasefire regime and the withdrawal of heavy weapons by the OSCE.69 The OSCE has thus extensively used ‘soft’ monitoring and mediation tools in response to the crisis in Ukraine. OSCE has included both external and internal players in mediation.70 Although the Minsk process has so far been unsuccessful in addressing the conflict’s resolution, the conflict in the east of Ukraine has been at least partly frozen and the international community has been included in the search for a way to de-escalate the conflict. It has also pressured for the reduction of risk of renewed escalation into an open war. The OSCE activities contributed to defusing the Ukraine conflict, and it proved the crucial role of the CiO.71

OSCE Special Representative Sajdik speaks at a press conference following a special meeting of the Trilateral Contact Group for the settlement of the Ukrainian conflict, on February 1, 2017. VIKTOR DRACHEV / Getty Images

OSCE Special Representative Sajdik speaks at a press conference following a special meeting of the Trilateral Contact Group for the settlement of the Ukrainian conflict, on February 1, 2017. VIKTOR DRACHEV / Getty Images

Looking back on the past years of the OSCE crisis management vis-à-vis Ukraine, “the involvement of the Organization focused mainly on two pillars: monitoring, and facilitating dialogue on the implementation of the Minsk agreements.”72 The activities of the OSCE at least enabled the international community to enter into the “seemingly” internal conflict, which confirmed that the general principle of non-intervention in internal affairs of states is relativized by joint sharing of obligations in the case of a drastic breach of the OSCE acquis.

Conclusion

It is evident that the key moments in the creation of the strategic culture of the OSCE fall into the period right after the end of the Cold War. At the time of cooperation, we can see in the documents that the states in the region have been able to share their notion of security and its resolution, which was reflected in the definition of parameters of security that can be of fundamental importance upon the characterization of the strategic culture of the OSCE. Further development has, nevertheless, demonstrated the inability of the OSCE to maintain stability and cooperation in the field of security within the OSCE area and the organization fell into crisis. Nevertheless, the violent conflict in the eastern part of Ukraine demonstrated that the OSCE participating states are able to establish a minimum consensus to activate the organization and use it in the effort to de-escalate the conflict. The answer corresponded to the features that were identified within the individual levels of approach of the OSCE to security. It is evident that it was successful in case of the violent conflict in Eastern Ukraine in which the OSCE intervened, and the behavior of Russia was considered by the majority of participating states aggressive, breaching both international law and the OSCE principles. The activity of the OSCE is, moreover, happening even in the situation in which the conflict, of a violent character, is still ongoing.

A specific history of the organization and its mission confirmed the limited ability to create a strategic culture also among the states that are mutual enemies

Despite the deepening crisis of the individual mechanisms, the OSCE maintained a position of a unique multilateral forum, which not only defines the principles, and standards of pan-European security, but it may be applied with certain limitations. The conflict in Ukraine, however, significantly modified the scope of the OSCE activities, with a focus shift to conflict mitigation and support solution. The strategic culture of the OSCE not only exists, but it also enables the participating states at least a limited reaction in the case of a threat of violence escalation in Europe. Recent research indicates that states are able to construct a strategic culture within the OSCE framework, and this strategic culture is subsequently reflected also in the activities of the organization. It is not clear that the relevance of the OSCE has potentially grown in this current crisis.

A specific history of the organization and its mission confirmed the limited ability to create a strategic culture also among the states that are mutual enemies. This paper has analyzed the basic features of the strategic culture of the OSCE, i.e. dialogue, security threats solved by cooperation and indivisibility of security, non-use of force, transparency, predictability and disarmament and interaction of internal and external security based on the analysis of fundamental political documents of the OSCE relating to security.

It is also evident that the strategic culture of the organization influenced the form of reaction and its extent. A paradoxical situation thus occurred in which the reaction under the OSCE heading was the most visible and enabled at least partial freezing of the conflict, also allowing the international community to gain a certain control of the conflict in Ukraine. It was nevertheless also evident that the ability to activate the OSCE is fully dependent on the will of its participating states. It would be interesting to study further how this fact is perceived by the participating states and whether this specific case will be somehow reflected in a reform of the OSCE.

Endnotes

- The article was written with the support of the specific research project of the University of Economics, Prague “The Reaction of the International Community on Actual Challenges of Destabilization of the Security Environment,” (IGS VŠE No. F2/99/2017).

- Peter Van Ham, “EU, NATO, OSCE, Interaction, Cooperation, and Confrontation,” in Gunther Hauser and Franz Kernic (eds.), European Security in Transition, (Bulington: Ashgate, 2006).

- Emanuel Adler and Michael Barnett, Security Communities, (Cambrigde: Cambrigde University Press, 1995).

- Michael Mosser, “Embracing ‘Embedded Security’: The OSCE’s Understated but Significant Role in the European Security Architecture,” European Security, Vol. 24 (2015), pp. 79-99.

- Victor Yves Ghebali, “The OSCE between Crisis and Reform: Towards a New Lease on Life,” Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF), (2005).

- See, Barry Buzan, “New Patterns of Global Security in the Twenty-first Century,” International Affairs, Vol. 67, No. 3 (1991); Barry Buzan, Ole Waever and Jaap deWilde, Security: A New Framework for Analysis, (Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1998); Alastair Iain Johnston, “Thinking about Strategic Culture,” International Security, Vol. 19, No. 4 (1995); Jeannie Johnson, Kerry Kartchner and Jeffrey Larssen, Strategic Culture and Weapons of Mass Destruction: Culturally Based Insights Into Comparative National Security Policymaking, (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009); Monica Gariup, European Security Culture, Language, Theory, Policy, (Burlington: Ashgate, 2009).

- Gariup, European Security Culture, Language, Theory, Policy.

- Ronnie Lipschutz (ed.), On Security, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995).

- Gariup, European Security Culture, Language, Theory, Policy.

- Johnston, “Thinking about Strategic Culture.”

- Johnston, “Thinking about Strategic Culture.”

- Jack L. Snyder, “The Soviet Strategic Culture: Implications for Limited Nuclear Operations,” RAND, (1997).

- Henry Mintzberg, “The Fall and Rise of Strategic Planning,” Harvard Business Review, Vol. 72, No.1 (1994).

- “İstanbul Document 1999,” OSCE.

- Colin Gray, Modern Strategy, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999).

- Gariup, European Security Culture, Language, Theory, Policy.

- Amitav Acharya, “Culture, Security, Multilateralism: The ‘ASEAN Way’ and Regional Order,” Contemporary Security Policy, Vol. 19, No. 1 (1998), pp. 55-84.

- Acharya, “Culture, Security, Multilateralism.”

- Significant resources which may help in defining the strategic culture of organizations include, Barry Buzan, “Is International Security Possible?” in Ken Booth (ed.), New Thinking about Strategy and International Security, (London: Harper Collins, 1991); Buzan, Waever and DeWilde, Security: A New Framework for Analysis; Gariup, European Security Culture, Language, Theory, Policy; Lipschutz, On Security; Adler and Barnett, Security Communities; Henry Mintzberg, “The Fall and Rise of Strategic Planning,” Harvard Business Review, Vol. 72, No. 1 (1994); Colin Gray, Modern Strategy, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999); Acharya; Johnston, “Thinking about Strategic Culture.”

- Patricia H. Thornton, William Ocasio and Michael Lounsbury, “The Institutional Logics Perspective,” in Royston Greenwood, Christine Oliver, Thomas B. Lawrence and Renate E. Meyer (eds.), Sage Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism, (Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Ltd., 2008), pp. 99-128.

- David E. McNabb, Research Methods for Political Science: Quantitative and Qualitative Methods, (New York: Armonk, 2004).

- “Astana Commemorative Declaration: Towards a Security Community,” OSCE, (Astana, 2010).

- Adler and Barnett, Security Communities.

- McNabb, Research Methods for Political Science: Quantitative and Qualitative Methods.

- Nelson Phillips and Cynthia Hardy, Discourse Analysis: Investigating Processes of Social Construction, (London: Sage Publication, 2002).

- Mohammed I. Alholjailan, “Thematic Analysis: A Critical Review of Its Process and Evaluation,” West East Journal of Social Sciences, Vol. 1, No. 1 (2012), pp. 39-47.

- Norman Fairclough, Language and Power, (London: Longman Inc., 2001).

- Janie Leatherman, From Cold War to Democratic Peace: Third Parties, Peaceful Change, and the OSCE, (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2003).

- Frank Evers, Martin Kahl and Wolfgang Zellner, The Culture of Dialogue: The OSCE Acquis 30 Years after Helsinki, (Hamburg: Institute for Peace Research and Security Policy, 2005).

- Victor Yves Ghebali, “Introducing the Code,” in Gert C. De Nooy (ed.), Cooperative Security, the OSCE, and Its Code of Conduct, (Hague: Nederlands Instituut voor Internationale Betrekkingen, 1996); Peter von Butler, “Negotiating the Code: A German View,” in De Nooy (ed.), Cooperative Security, the OSCE, and Its Code of Conduct; Victor Yves Ghebali and Alexandr Lambert, The OSCE Code of Conduct on Politico-Military Aspects of Security, Anatomy and Implementation, (Leiden: Martius Nijhoff, 2005).

- Hans-Joachim Schmidt, “The Link between Conventional Arms Control and Crisis Management,” OSCE Yearbook 2015, (Baden-Baden: IFSH, 2016).

- Ghebali, “The OSCE Between Crisis and Reform: Towards a New Lease on Life.”

- Richter Solveig and Wolfgang Zellner, “Ein Neues Helsinki Für Die OSZE? Chancen Für Eine Wiederbelebung Des Europäischen Sicherheitsdialogs,” SWP-Aktuell, (November 2008), retrieved from https://www.swp-berlin.org/publikation/ein-neues-helsinki-fuer-die-osze/.

- Solveig and Zellner, “Ein Neues Helsinki Für Die OSZE? Chancen Für Eine Wiederbelebung Des Europäischen Sicherheitsdialogs.”

- Evers, Kahl and Zellner, The Culture of Dialogue The OSCE Acquis 30 Years after Helsinki.

- Niels Moller-Gulland, “The Forum for Security Co-Operation and Related Security Issues,” in Michael Lucas (ed.), The CSCE in the 1990s: Constructing European Security and Cooperation, (Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, 1993).

- Adler and Barnett, Security Communities.

- Michael Mihalka, “Cooperative Security: From Theory to Practice,” in Richard Cohen and Michael Mihalka, (eds.), Cooperative Security: New Horizons for International Order, (Garmisch-Partenkirchen European Centre for Security Studies, George C. Marshall, 2001).

- David Calleo, “A Choice of Europes,” The National Interest, Vol. 63, No. 2 (2001), pp. 5-16.

- Ghebali, “The OSCE Between Crisis and Reform.”

- Gariup, European Security Culture, Language, Theory, Policy.

- “İstanbul Document 1999.”

- “İstanbul Document 1999.”

- “İstanbul Document 1999.”

- Ghebali, “The OSCE Between Crisis and Reform.”

- “İstanbul Document 1999.”

- “İstanbul Document 1999.”

- Elena Kropatscheva, “The Evolution of Russia’s OSCE Policy: From the Promises of the Helsinki Final Act to the Ukrainian Crisis,” Journal of Contemporary European Studies, Vol. 23, No.1 (2015), pp. 6-24.

- Michaela Anna Šimáková, “The European Union in the OSCE in the Light of the Ukrainian Crisis: Trading Actorness for Effectiveness?” EU Diplomacy Paper, Vol. 3, (Brugge: College of Europe, 2016).

- Rolf Welberts, “The OSCE Missions to the Successor States of the Former Soviet Union,” OSCE Yearbook 1997, (Baden-Baden: Nomos, 1998).

- Volodymyr Kulyk, “Revisiting a Success Story: Implementation of the Recommendations of the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities to Ukraine, 1994-2001,”CORE Working Paper 6, (2002).

- Denis Sammut and Joseph D´Urso, “The Special Monitoring Mission in Ukraine: A Useful but Flawed OSCE Tool,” Policy Brief, (Brussel: European Policy Center, 2015).

- Solveig and Zellner, “Ein Neues Helsinki Für Die OSZE? Chancen Für Eine Wiederbelebung Des Europäischen Sicherheitsdialogs.”

- Christian Nünlist, “No. 202: The OSCE and the Future of European Security,” CSS Analyses in Security Policy, (Zurich: ETH Zurich, 2015).

- Thomas Greminger, “The 2014 Ukraine Crisis: Curse and Opportunity for the Swiss Chairmanship, Zurich, 11–12,” in Nünlist Christian and Svarin David (eds.), Perspectives on the Role of the OSCE in the Ukraine Crisis, (Zurich: Center for Security Studies, 2014).

- Maxime Lefebvre, “The Ukraine Crisis and the Role of the OSCE from a French Perspective,” OSCE Yearbook 2015, p. 102.

- Arie Bloed, “The OSCE Main Political Bodies and Their Role in Conflict Prevention and Crisis Management,” in Michael Bothe, Natalino Ronzitti and Allan Rosas (eds.), An Evolving European Security Order, The OSCE in the Maintenance of Peace and Security: Conflict Prevention, Crisis Management and Peaceful Settlement of Disputes, (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1997).

- Lefebvre, “The Ukraine Crisis and the Role of the OSCE from a French Perspective,” p. 101.

- Wolfgang Zelner, “Conflict Management in Confrontational Political Environment,” in Samuel Goda, Olexandr Tytarchuk and Maksym Khylko (eds.), International Crisis Management: NATO, EU, OSCE and Civil Society, Collected Essays on Best Practices and Lessons Learned, (Amsterdam: IOS Press, 2016).

- Kropatscheva, “The Evolution of Russia’s OSCE Policy.”

- Lefebvre, “The Ukraine Crisis and the Role of the OSCE from a French Perspective.”

- “Decision No. 1117, Deployment of an OSCE Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine,” OSCE, (March 21, 2014), retrieved from https://www.osce.org/pc/116747?download=true.

- “Decision No. 1117, Deployment of an OSCE Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine.”

- Sammut and D´Urso, “The Special Monitoring Mission in Ukraine.”

- “Decision No. 1117, Deployment of an OSCE Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine.”

- “Decision No. 1117, Deployment of an OSCE Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine.”

- Hrant Konstanyan and Stefan Meister, “Ukraine, Russia and the EU Breaking the Deadlock in the Minsk Process,” CEPS Working Document, No. 423, (June 2016).

- Pál Dunay, “The OSCE in the East: The Lesser Evil,” in Christian Nünlist and David Svarin (eds.), Perspectives on the Role of the OSCE in the Ukraine Crisis, (Zurich: Center for Security Studies, 2014), pp. 17-23.

- “Package of Measures for the Implementation of the Minsk Agreements,” (February 12, 2015).

- Mir Mubashir, Engjellushe Morina, and Luxshi Vimalarajah, OSCE Support to Insider Mediation Strengthening Mediation Capacities, Networking and Complementarity (Based on Case Studies in Kosovo, Kyrgyzstan and Ukraine), (Berlin: Berghof Foundation, 2016).

- Nunlist, “No. 202: The OSCE and the Future of European Security. "

- Claus Neukirch, “The Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine in Its Second Year: Ongoing OSCE Conflict Management in Ukraine,” OSCE Yearbook 2015, (Baden-Baden: OSCE, 2016).