Evaluations of Turkish foreign policy have drastically changed over the past few years. The new policy of the incoming AK Party government had been almost unanimously applauded as a “paradigm change” from a “post-cold war warrior” or a “regional coercive power” into a “benign”, if not “soft” power,1 or as the (albeit incomplete) change from “securitized nationalism” to “desecuritised liberalism.”2 However, further analysis of the more recent Turkish foreign policy finds very divergent evaluations. Some authors within Turkey have described it as an unfolding of policy principles,3 whereas other studies have debated whether Turkey has become a “normative power” or could join the BRIC states.4 In contrast, European and American observers’ criticisms of Turkey’s “over-confidence”5 have turned into verdicts that “Turkey’s plan to be a standalone power in the region is nowhere near fruition.”6 Some pundits have gone as far as to claim that Turkey’s “foreign policy is falling apart victim to Mr. Erdoğan’s hubris.”7

This paper will argue that Turkish foreign policy has in fact changed in relation to the basic parameters of foreign policy role concepts. Thus, this essay will try to “make sense” of the changes in Turkish foreign policy by interpreting it as the quest for a new foreign policy role once the incoming AK Party government abandoned the “traditional republican foreign policy”8 which had characterized most of Turkey’s history and has aptly been described as a “defensive nationalism.”9 In contrast, the AK Party government began with a foreign policy approach that strongly prioritized cooperation, expressed in the often quoted “no problem-with neighbors” principle,10 and aimed at rechanneling national aspirations from security concerns to economic prosperity and international trade. In addition, it strongly supported international organizations and prioritized Turkey’s integration into the supranational structures of the EU.

The AK Party government began with a foreign policy approach that strongly prioritized cooperation, expressed in the often quoted no problem-with neighbors principle

The shift towards a “regional project” – first by using visa exemptions and free trade arrangements and later also by taking sides in the domestic conflicts in Iraq, Syria and Egypt – and towards the emphasis on multiple (including military) resources of power and the ambition to act as a representative of a group of (Muslim) states in international organizations display the characteristics of a regional power.11 As a foreign policy analyst put it, “the AK Party envisioned Turkey as the area’s Brazil, a rising economic power with a burning desire to shape regional events.”12 The most visible and explicit change in Turkey’s foreign policy role has been from its prior aim to be “a bridge between EU and the Islamic world”13 to the more recent aim to “be the owner, pioneer and servant of the new Middle East.”14

In order to grasp the range of foreign policy options and changes in the last decade, this essay will first discuss civilian power and regional power as two ideal types of foreign policy roles. According to Max Weber’s definition, “concrete individual phenomena are arranged into a unified analytical construct”, the ideal type, in a methodological “utopia [that] cannot be found empirically anywhere in reality.”15 Using this analytical angle, the essay will link an influential strand of the recent literature on regional powers to the earlier debate on civilian power. Both ideal types display some astonishing similarities, but still represent different concepts in the core dimensions of foreign policy: the position towards conflict and cooperation, military and non-military means of foreign policy, and the state’s role in international and transnational organizations.

The essay will then demonstrate that the foreign policy of the incoming AK Party government introduced a new foreign policy concept with many traits of a civilian power (2002-2005). Subsequently, Turkish foreign policy was more willing to enter into conflicts with the European Union and the United States, and shifted its attention towards the Middle East (2005-2010). However, the basic parameters of foreign policy shifted to a regional power concept only after the Mavi Marmara incident (2010). Although Turkish policymakers have described Turkey as a “central country” and therefore multi-regional power, Turkish policies have since then displayed the characteristics of the regional power ideal type. Moreover, Turkey’s conception of a regional power has clearly departed from its early civilian power role, given the use of confrontation (towards Israel) as a means to promote a regional project and the taking of sides in domestic conflicts of other states in the region (Syria, Iraq and Egypt).16 Although it is beyond the scope of this essay to fully analyze the interaction between domestic and international developments, the paper will also highlight that different foreign policy roles have different domestic “uses” - corresponding with the analyses of the respective ideal types, particularly in the case of civilian power.

“Civilian Power” as a Foreign Policy Role Concept

The very notion of a foreign policy role concept has been developed in the analysis of “civilian power” as a new form of foreign policy that largely departs from the use of military power and the isolated pursuit of national interests. Thus, the foreign policy of a state reflects its perception of international relations alongside the values and norms its leaders feel committed to and intend to promote. According to Hanns Maull, three elements constitute civilian power: 1) “the acceptance of the necessity of cooperation with others in the pursuit of international objectives”; 2) “the concentration on non-military, primarily economic means to secure national goals, with military power left as a residual instrument”; and 3) the “willingness to develop supranational structures” and a “determined insistence on integrating itself into multilateral structures,” which consequently implies relinquishing national sovereignty.17 Maull then interpreted civilian power from the perspective of the international system and defined it as a “foreign policy role concept” that Japan and Germany “developed for themselves” in reaction to the devastating military defeat and subsequent loss of national sovereignty after the Second World War. However, its success “depended crucially on the USA as a cooperative, understanding hegemon in a heavily multilateralized and institutionalized international order.”18

Subsequently, Germany and Japan became prototypes of the modern trading state and shifted “the emphasis of international relations to enhancing prosperity.” In the domestic context, this process brought about a redefinition of the national identity of former “military nations”, wherein “national aspirations were re-channeled towards economic achievements.”19 First restricted by Allied Forces’ obligations, Germany and Japan subsequently deliberately chose not to fully utilize the military potential stemming from their population size and rapid economic growth. Both states renounced nuclear weapons and strongly limited military expenditure in relation to a swiftly growing GDP. Until today Germany’s military expenditure has reached only half the percentage of the national GDP of other European states (see Table 1). Moreover, Germany and Japan gave up national sovereignty, preferring close integration into and reliance on the protective shield of NATO (and ultimately the US). In addition – and reflecting their geographic position at the margin of the “Western community” – they also became very active within the UN, contributing to large parts of the UN budget, promoting disarmament and peaceful conflict resolutions, and turning into salient donors in development cooperation.

Turkish ship Mavi Marmara arrives at Istanbul’s Sarayburnu port as people wave Turkish and Palestinian flags on December 26, 2010. The Israeli navy raided on May 31, 2010 the Turkish ship Mavi Marmara. | AFP / Mustafa Özer

Turkish ship Mavi Marmara arrives at Istanbul’s Sarayburnu port as people wave Turkish and Palestinian flags on December 26, 2010. The Israeli navy raided on May 31, 2010 the Turkish ship Mavi Marmara. | AFP / Mustafa Özer

Recently, civilian power has been used as a synonym for normative power.20 However, the diffusion of norms – such as the rule of law, democracy and human rights – which is the core element of normative power (and for some scholars, the major aspect of EU foreign policy) is in the foreign policy role concept of civilian power secondary to peaceful conflict prevention and resolution.21 Accordingly, the foreign policy of both Germany and Japan was, until the 1990s, characterized by a “profound reluctance to assume larger military roles,”22 even in international military interventions. Leaving aside the question of whether Germany, given its increasing involvement in peace-keeping missions, can today still be considered a civilian power, coalition-building for peaceful conflict resolution is much more characteristic of the civilian power role than participation in military action, even if supported by transnational or international organizations and norms.23

The foreign policy of a state reflects its perception of international relations alongside the values and norms its leaders feel committed to and intend to promote

The very concept of civilian power relates foreign policy to domestic politics. The double meaning of the word “civilian” reflects both the aim of “civilizing” international relations, as well as the aim to strengthen the civilian prerogative over the military by demilitarizing (or even “desecuritizing”) the very concept of foreign policy. Thomas Berger pointed out that the “new” Japanese and German foreign and security policies implied the intention of a recalibration of militarist societies which had developed after German nation-state building and the Meiji restoration in Japan. Both post-war Christian democrats in Germany and liberals in Japan were determined to prevent the military from playing the kind of political role it had played before 1945, as they “were deeply suspicious of the armed forces and blamed them for the failure of party democracy in the 1930s.”24 The new foreign policy approach in Germany and Japan kept the military under strict civilian control and, during the rearmament in the 1950s, civil-military relations were clearly designed to ban the formerly dominant military ethos and the existence of the army as a “state-in-a-state.”

Regional Power as a Foreign Policy Role Concept

Like the concept of civilian power, the concept of regional power has in the last decade been developed in relation to a specific international context - an increasingly multi-polar world in which the United States is the only remaining superpower, but is losing influence to a number of other states. The increasingly broad literature on regional powers can be divided into two major strands: one that focuses on the range of characteristics of regional powers and their positions within a “regional security system”25, and the other that elaborates on communalities between current regional powers in order to develop an ideal type of regional power 26. This second strand of literature states that the influence today’s emerging powers is mostly geographically limited and based on economic power. Detlef Nolte claims that in the current state of international relations, regional powers can only exert “leadership in cooperation” and that “regional hegemony is in the current state of world politics only possible as cooperative hegemony, through incentives and leadership (as opposed to coercion)”27. Therefore and to limit the leverage of great powers, regional powers hold a preference for multilateralism and institution-building.

In this debate, the initial definition of regional power by economic and military resources (capability) was supplemented by the focus on a state’s ability to use these resources to “convince a sufficient number of states in the region to rally around its regional project”28 (influence) and the recognition by other states in the region (perception). Robert Kappel has listed as criteria for economic regional powers that they influence the monetary and credit policies of their neighboring countries, contribute significantly to world trade and regional economic growth and aim at playing a core role in regional economic development and cooperation29. Other empirical studies have focused on the states’ political capability to establish regional cooperation and institutions and to act as representatives of other states in international organizations.

If we take a dynamic perspective on the making of regional powers, the foreign policy of a state wishing to become a regional power consists of 1) the articulation of a common regional identity or project and its influence on the establishment of regional governance structures, 2) the accumulation of military, economic and ideational resources, with priority given to a central position in economic relations, and 3) the claim to represent other states in the region in international organizations. Both Brazil and South Africa, arguably the most common examples of regional powers, have claimed leadership in their region and have risen to leading roles in MERCOSUR and SDAC, respectively. South Africa, for instance, has achieved an overarching status in regional economics whilst renouncing some military options, including the development or proliferation of nuclear weapons. Moreover, it claimed to be a model for the development of African states as well as a representative of the interests of African and other underdeveloped and debt-ridden states in international organizations30. Many other states have been included in different classifications of regional powers, ranging from India, China, Saudi-Arabia, Indonesia, Mexico and Egypt to, most recently, Turkey.

As the concept of regional power has only recently gained prominence in foreign policy analysis, there is little systematic work on its domestic dimension. However, there is some evidence that internal coherence is rather one of the domestic aims of the regional power role concept than its precondition. In the case of South Africa, the ambition to represent the “disadvantaged” African states on a global scale, has cemented the domestic alliance of the governing party, in particular by pacifying the more (left-wing) radical part.31

The foreign policy concepts of civilian power and regional power both emphasize contribution to public goods, particularly economic cooperation and peaceful conflict regulation. But in the case of regional powers, both are linked to the claim of a leadership or custodianship position in a particular region, i.e. the aim of shaping a “regional project” according to own policy preferences. Moreover, civilian powers reject confrontation and the use of military strength for principled reasons, deliberately renouncing military power and resorting to confrontation only in the most extreme cases. In contrast, regional powers tend to renounce military power for instrumental reasons; they tend to keep it as one resource of regional leadership and regard confrontation as a viable option. In fact, military strength is given as a prerequisite for a regional power status, whereas it is negatively correlated to the role concept of civilian power. Considering the variety within the conception of regional power, it is conceivable that the roles of civilian and regional powers might converge, however, only in the very specific circumstances of a multi-polar and pacified regional security complex with many transnational institutions. One may think of contemporary Germany as an example of a regional power which still exhibits to some extent the characteristics of the civilian power role: the downplaying of military strength, non-interference in the domestic policies of neighboring states and the insisting on peaceful conflict resolution (even to the point of reluctance for participating in international missions).

Once the AK Party was in government, it carried out a number of diplomatic activities to pacify old conflicts with neighbor states

The Foreign Policy of the Incoming AK Party Government: From “Defensive Nationalism” towards “Civilian Power“?

For decades, Turkey’s foreign policy role concept was determined by its nation-state building history. Turkey was a late-comer in entering the stage of European nation-states after the downfall of the Ottoman Empire. The military and strategic skills of nation-state builder Mustafa Kemal Atatürk prevented a coalition of western European powers from dividing the largest part of the Turkish territory as determined in the Treaty of Sevres (1920). Although never ratified, the Treaty of Sevres became a national “founding myth” and perpetuated the notion of being surrounded by a world of enemies32. As a consequence, Turkey’s foreign policy became characterized by a “defensive nationalism”33, as Ziya Öniş has succinctly put it, by focusing on (perceived) threats to the national sovereignty and territorial integrity of Turkey. The prioritization of “national security and military readiness” by “the traditional republican foreign-policy making establishment”34 was based on the low level of transnational economic cooperation with Asian states and the geographical position of Turkey that facilitated the flow of national minorities across borders. As late as the 1990s, a leading figure in Turkish diplomacy claimed that Turkey should be prepared to lead “two and a half wars” against Greece, Syria and the Kurdish PKK.35

In the international context of the Cold War, Turkey allied with the West; NATO membership and close military cooperation with the US and Israel in the procurement of arms served to satisfy Turkey’s security concerns. However, membership in an international organization was instrumental and did not stop hostile relations with Greece, which was a member of NATO as well. On the contrary, Turkey aimed at accession to the European Union in order to gain an advantage, or at least prevent being at a disadvantage, in the power balance with Greece. Thus, as a foreign policy role concept, “defensive nationalism” kept cooperation mainly for security concerns, strongly focusing on military capacity and perceiving international organizations as a “security shield.”

The foreign policy of the AK Party government displayed a significant shift from an emphasis on military strength to prioritizing economic cooperation

Due to the stark contrast with this defensive nationalism, the incoming AK Party government’s foreign policy attracted huge attention. Most of the analyses attribute three core characteristics to the AK Party governments’ initial foreign policy after its ascent to power in 2002 (as will be analyzed in the following paragraphs): the prioritization of cooperation; the shift from military or security considerations to economic aims (up to the point of a transition into a “trading state”); and strong support for transnational and international organizations. These three elements correspond rather neatly with the characteristics of a “civilian power.”

From Confrontation to the Prioritization of Cooperation

Once the AK Party was in government, it carried out a number of diplomatic activities to pacify old conflicts with neighbor states. Relations with Greece improved considerably after the AK Party government changed Turkey’s approach to the Cyprus question. It withdrew support for the intransigent Turkish Cypriots and strongly pushed for the approval of a plan for a unified federal state put forward by UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan. It significantly improved the difficult relations with Armenia, strained by the memories of the deportation of Armenians in 1915, which is considered genocide by Armenians. The AK Party also improved relations with Iraq and, in particular, Syria. Building on the Adana accords with Syria in October 1998, mutual visits followed in 2003. Syrian-Turkish trade increased drastically and was further supported by the establishment of a common free trade area.

The arrangement with the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) in northern Iraq, which was perceived as a major threat to Turkey’s territorial integrity after the military defeat of Saddam Hussein, made the changes in foreign policy particularly visible. In stark contrast to the 1995 intervention and against pressure from the Turkish military, the AK Party government sought an agreement with the United States and the Iraqi government before engaging in cross-border operations between December 2007 and February 2008 against PKK fighters, which entered Turkish territory from Iraq. Moreover, Turkish President Abdullah Gül broke a precedent when he had direct talks with Massoud Barzani, head of the KRG, on March 23, 2009.

It has become a commonplace to attribute much of the change in Turkish foreign policy to the influence of Ahmet Davutoğlu, long-time architect of the AK Party’s foreign policy and Turkey’s foreign minister since May 2009. Based on the insight that “a comprehensive civilizational dialogue is needed for a globally legitimate order,” Davutoğlu had in his academic work called for Turkey to move from its traditional “threat assessment approach” towards an “active engagement in regional political systems in the Middle East, Asia, the Balkans and Transcaucasia.” Davutoğlu stated that Turkey possesses a “strategic depth” that it had failed to exploit; it should act as a “central country” and break away from a static and single-parameter policy. Turkish foreign policy analysts have recently argued that the “no-problems-with-neighbors” principle is only one aspect of Davutoğlu’s multifaceted approach.36 However, in the AK Party’s first few years in government, the emphasis was clearly on becoming a “problem solver” and contributing to “global and regional peace.”37 In line with this generalized support for cooperation, Turkey aimed to build a reputation as a “facilitator of cooperation” and repeatedly mediated in conflicts between Pakistan and Afghanistan, Syria and Israel, and Hamas and Israel.

The Shift from Military to Economic Aims in Foreign Policy

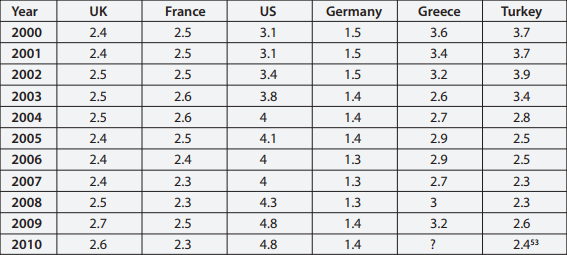

The foreign policy of the AK Party government displayed a significant shift from an emphasis on military strength to prioritizing economic cooperation. Building on reforms after the 1999-2001 crises, the AK Party’s economic policies led to a period of continuous growth and stability with an average growth rate of 6 per cent. The changing importance of foreign economic relations on the one hand and of military strength on the other is reflected in the sharp rise in foreign direct investment (FDI) from $1.1 billion in 2001 to an average of $20 billion between 2006 to 200838 whilst Turkey’s military expenditure strongly decreased in terms of percentage of GDP from 3.9 per cent in 2002 to 2.1 per cent in 2007, falling back in relative terms behind Greece, France and Britain (see table 1).

Given Turkey’s geostrategic position, diplomacy and economic cooperation were mutually reinforcing to increase hitherto rather limited trade relations. For instance, in the aftermath of the conflict between Georgia and Russia, Ankara streamlined a diplomatic initiative championing the idea of a “Caucasus Solidarity and Cooperation Platform,” including Russia, Turkey, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia. The emphasis on the mutual gains of economic cooperation was further strengthened by Turkey’s ambition to become a key player in regional energy politics as an “energy hub” and pivotal country for the transition of energy supplies. Therefore, Kemal Kirici has even argued that Turkey would develop into a “trading state.”39

Table 1: Defence spending as percentage of GDP in selected countries.

Source: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SİPRİ) http://milexdata.sipri.org/ accessed

November 15, 2013.

Support for Trans- and International Organizations

Another major innovation of the AK Party government’s policies in comparison to previous Turkish foreign policy was the policy activism in international organizations. Turkey assumed a front-running role in a number of international organizations after the AK Party’s ascent to government. Turkey’s most salient success was the non-permanent seat in the UN Security Council in 2009-2010, which was acquired with the support of many African countries. It also took over the chairmanship of the Council of Ministers within the Council of Europe and became an observer in the African Union, the Arab League, the Association of Caribbean States (ACS) and the Organization of the American States (OAS). In addition, Turkey emerged as a donor country in the United Nations with development assistance exceeding US$700 million in 2008. Turkey also started to play a prominent role in the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC); the election of Turkish professor Ihsanoglu to the position of Secretary-General by democratic vote was the first in the history of the OIC. This went hand in hand with a new discourse “highlighting the moral/normative aspect beyond the confines of narrow self-interest”40 and Turkey’s role as an “internationalist humanitarian actor.”41

During the AK Party’s first years in government, Turkey’s role in other regional organizations was clearly connected to Turkey’s rapprochement with the EU. Davutoğlu argued that “if Turkey does not have a solid stance in Asia, it would have very limited chances with the EU.”42 President Gül stated that Turkey’s EU membership would promote “the harmony of a Muslim society with predominantly Christian societies” and Erdoğan emphasized that the European Union would “gain a bridge between the EU and the 1.5 billion-strong Islamic world.”43 Therefore, much public attention was given to Turkey’s co-sponsorship of the “Alliance of Civilizations” initiative (AoC) with Spain, originally proposed by Spanish Prime Minister Jose Luis Zapatero in September 2004 and taken up by UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan.

A major innovation of the AK Party government’s policies in comparison to previous Turkish foreign policy was the policy activism in international organizations

There is an interesting parallel between the foreign policy of the early AK Party government and the civilian powers of Japan and Germany in the use of a foreign policy role to curb the influence of the military and, reminiscent of the German relationship to the European Community, the use of regional integration as a means to lock-in economic and political liberalization. It has become “conventional wisdom” that the priority assigned to Turkey’s bid for EU membership in Turkish foreign policy was part of the AK Party’s quest for a new form of legitimacy after the ousting of its predecessor party, the Welfare Party. Moreover, it was instrumental in reducing the influence of the military whose intervention was repeatedly condemned by EU progress reports. In fact, reform packages in preparation of the EU’s decision to start accession negotiations with Turkey reduced the influence of the military in the National Security Council. Moreover, the significant reduction in military spending (see table 1) and emphasis on economic prosperity and cooperation combined with the downplaying of security concerns reduced the role of the military.

More Assertiveness, Limited Change (2005-2010)

The Turkish foreign policy role concept of being a “mediator between Europe and the Muslim world” suffered a setback when the accession negotiations between Turkey and the EU, which started in 2005, were impeded by the predicament of the Cyprus question. In an ill-advised move, the EU accepted the (Greek) Republic of Cyprus as a member, disregarding the negotiations for a reunification of the island conducted by the United Nations. Whereas the AK Party government strongly pushed for the acceptance of the so-called Annan plan, Greek Cypriots rejected the plan in a public referendum in 2004. As the EU also did not take action to stop the isolation of the Turkish part of Cyprus, Turkey did not open its ports and airports to Greek Cyprus, which was an official breach of the Ankara protocol Turkey had signed as a precondition for the accession negotiations. Subsequently, the EU Council of Ministers blocked the opening of several chapters, a move which was regarded by virtually the entire Turkish public as thoroughly unfair.

There is an interesting parallel between the foreign policy of the early AK Party government and the civilian powers of Japan and Germany in the use of a foreign policy role to curb the influence of the military

The perspective of EU accession further faded after German Chancellor Merkel and French President Sarkozy, in a reversal of the predecessors’ positions, objected to the Turkish bid in principle and French President Sarkozy blocked chapters that allegedly would determine Turkish accession. These actions gave Turkey the impression that there was a principled and insurmountable blockade to membership, causing public support for EU membership to drop from around 75 percent to 50 percent in 2005. However, despite the public disappointment about the EU’s policies, EU accession and EU norms still played an important role in the conflicts in 2007 and 2008 regarding the election of Abdullah Gül as President and the indictment of the AK Party by the Constitutional Court. Statements of EU officials and institutions legitimized the AK Party’s position vis-à-vis the military and Kemalist state elite. Even the Turkish constitutional reforms enacted in 2010 were justified as complying with EU requirements.

In addition, whilst within the EU many felt that “Turkey has been moving away from aligning its foreign policy with the EU,”44 Turkish foreign policy remained within the role concept as a mediator in conflicts; a role the EU was neither eager nor capable of adopting.45 A case in point was the reception of the Hamas leadership in Ankara in 2006, which caused immediate concern in the US and the EU. However, the incoming Obama administration welcomed the Turkish mediation in cautiously establishing contact with Hamas, which was previously refused by the Bush administration. Moreover, the AK Party maintained close cooperation with Israel and Turkey’s role as a potential peacemaker was explicitly supported by Israel’s President Peres. Indirect talks between Syrian and Israeli officials started in Istanbul with Turkish diplomats acting as mediators.

EU Enlargement Commissioner Stefan Fule and EU Minister - Chief Negotiator Mevlut Cavusoglu, appointed as the Foreign Minister, smile while taking part in a meeting of the working group on Chapter 23 of Turkey’s EU membership bid in Ankara, Turkey on June 17, 2014. | AFP / Adem Altan

EU Enlargement Commissioner Stefan Fule and EU Minister - Chief Negotiator Mevlut Cavusoglu, appointed as the Foreign Minister, smile while taking part in a meeting of the working group on Chapter 23 of Turkey’s EU membership bid in Ankara, Turkey on June 17, 2014. | AFP / Adem Altan

The insistence on peaceful conflict resolution among sovereign states also continued to characterize Turkey’s stance in international relations, particularly in the conflicts in Iraq and Sudan, although it put Turkey in opposition to the US and the EU. During its turn as non-permanent member of the UN Security Council in 2009-2010, Turkey voted together with Brazil against the UN resolution imposing sanctions on Iran because of its nuclear program. The Turkish government also refused to condemn Sudan’s ruler, Omar al-Baschir, who was accused of mass murder in the Darfur region of Sudan, and tried to postpone the International Court of Justice’s warrant by a Security Council decision. However, in the Iranian case, the Turkish government not only pointed out that Turkey was much more strongly affected by additional sanctions than western European states; it also proposed a Turkish-Brazilian initiative to control the Iranian nuclear program through the exchange of enriched Uranium material. In a similar vein, Turkey engaged in a peace initiative for Sudan.

Towards a New Role Concept as “Regional Power” (Since 2010)

It was the confrontation between Turkey and Israel after the Israeli raid on an aid ship infringing the Gaza blockade in May 2010 that marked a clear break in the Turkish foreign policy role concept. Turkey expelled the Israeli ambassador and other senior diplomats, suspended military agreements with Israel, and threatened to send naval vessels to escort future aid convoys trying to break Israel’s blockade of Gaza. The Turkish government adopted an anti-Israeli rhetoric and accused Israel of committing “an act of state terrorism and savagery.” Moreover, when Greek Cypriot and Israeli authorities (next to other states) in 2011 signed an exclusive economic zone agreement establishing their maritime borders, Ankara rejected any such delimitation and announced the freezing of all contacts with the EU Council of Ministers during the 6 months of (Greek) Cyprus’ presidency in 2012.

The Mavi Marmara incident did by no means mark a return to the earlier “defensive nationalism.” However, it did indicate that the Turkish government renounced the position of a mediator in the conflict between Arab states and Israel in order to play to the tribunes of the “Arab masses” - the Turkish government used the confrontation with Israel as a means of increasing its influence in the Arab regions. In domestic policies, the divergent positions on the government’s support for the Mavi Marmara convoy marked the beginning of the escalation of tension with the Fetullah Gülen movement. Since then, Turkish foreign policies demonstrated (as will be analyzed in the following paragraphs) significant change in position towards cooperation and confrontation, the investment in military and economic power resources and the role in international organizations.

Table 2: Different ideal types of foreign policy role concepts.

From “Mediator” to the Claim of Leadership

An emerging public discourse described Turkey as a “leader country,” or a “regional player with an influence that exceeds its physical borders”.46 In the course of his so-called “Arab spring tour” in summer 2011, Erdoğan explicitly encouraged the new political forces in the Arab states to follow the Turkish model of economic development and of a type of secularism that is not identical to the “Anglo-Saxon or Western model”.47 During its first years in government, the AK Party had downplayed its religious roots and, as Meliha Altunişik noted, had stressed that it did not want to be a model for anyone.48 In contrast, Saban Kardaş recently concluded that Turkish “leaders made clear their perception of Turkey as destined to play leading roles in the region, even framing it in highly idealistic and cultural terms”. He pointed out that the AK Party government’s concept as a “central country” implied that Turkey is a regional power in the Balkans, the Black Sea and Caucasus regions and the Middle East at the same time. However, Kardaş conceded that in the Black Sea and Caucasus regions “Turkey is overwhelmed by Russia”49.

In contrast, Turkey had already become an advocate of a free-trade, integrationist position and has pursued an “aggressive policy to increase Turkey’s economic engagement in the Middle East” and Turkey’s ambition for regional integration found expression in the establishment of a common free trade area with Syria, Jordan and Lebanon. The idea was that Turkey, Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon would come together under a customs and political union. Visa requirements for Moroccan and Tunisian nationals were lifted in 2007 and for Jordanian, Lebanese and Syrian nationals in 2009. As Kemal Kirişci stated in 2012, Davutoğlu’s aspiration for “an integrated Middle East where people and goods can move freely ‘from Kars to the Atlantic’” would be “actually reminiscent of the vision of the founding fathers of the EU”.50

The Turkish foreign policy role concept of being a “mediator between Europe and the Muslim world” suffered a setback

Moreover, beyond the continuous use of “Israel bashing” in pursuit of its regional project, the Turkish government started to support political forces within Arab states in a reversal of its previous stance as a “sovereign-state defender”. In the case of Libya, Turkey first spoke out against the NATO intervention and delivering weapons to the rebels, thus, against the EU’s position (with the noteworthy dissent of the German government). In the 2010 Iraqi election, Ankara backed the pan-Iraqi bloc headed by Ayad Allawi, but Allawi lost to Nuri al-Maliki, seen by Ankara as an “Iranian pawn”. Subsequently, the Turkish government started to support the Iraqi opposition as well as Islamic parties in places like Egypt and Syria which, according to the AK Party’s logic, could moderate and come to power through democratic elections. For Turkey, such an outcome promised the added benefit of creating natural regional allies. With the Muslim Brotherhood’s initial rise to power in Egypt, Turkey’s vision seemed to be coming to fruition. The Turkish government also started to host and arm members of the Syrian opposition, in particular the Muslim Brotherhood, to help it emerge as the leader of the country’s opposition. Moreover, in a drastic reversal of the earlier rapprochement to Syria, Erdoğan publicly called for Assad’s resignation.

From “Trading State” to Multiple-resources Based Power

The Turkish government began to depict Turkey as a regional power with manifold economic, military and soft power resources. After a decade in government it could point to an impressive economic record, making Turkey one of the fastest growing economies in the world when GDP growth reached 8.9 per cent in 2010. At the same time, inflation rates were kept below 10 per cent and state debt was reduced from 75 to about 45 per cent of GDP. Turkish trade volume strongly increased, especially among the country’s neighbors. Trade with the EU remained the largest and most technologically advanced aspect of this trade volume, however, its share fell from a peak of 56 per cent of overall trade in 1999 to about 41 per cent in 2008.51 Turkey’s economic position became central for an entire area; her economy produces half the equivalent of the entire output of the Middle East and North Africa. Thus, regional integration became an interest of Turkish economic actors as Turkey’s foreign direct investment increased from $ 890 million in 2001 to $ 5,318 million in 200952.

The insistence on peaceful conflict resolution among sovereign states also continued to characterize Turkey’s stance in international relations, particularly in the conflicts in Iraq and Sudan

However, military threats also returned to the agenda when the Turkish government asserted its military presence in the Mediterranean Sea in the conflicts with Israel and Cyprus and flexed its muscles in the conflict with Syria. Military expenditure that had been reduced considerably in the first years of the AK Party government started to rise again (see table 153). Lastly, the AK Party government began to point to Turkey’s new “soft power”. The concept, which characterizes “influence other than coercion”, particularly the attraction of values and policies54, has often remained vague. In the Turkish case, it certainly reflects the ambitions of the Turkish government to bolster its influence in the region by promoting transnational relations. Besides fostering visa exemption regulations, the Turkish government has strongly promoted an increased role of non-state actors in foreign policy, as demonstrated by its participation in the Turkish African Civil Society Forum, which includes 80 civil society organizations. Furthermore, it has strongly increased the number of university scholarships and the Turkish state office for religious affairs, Diyanet, has increasingly promoted the education of African Imams.

From Support for International Institutions to “Revisionist Power”

Turkey’s aspiration for a major role in world politics was explicitly highlighted, for instance by Davutoğlu’s claim of “a transformation for Turkey from a central country to a global power” and Erdoğan’s statement that Turkey is “becoming a global player and this is an irreversible process”.55 As Saban Kardaş put it, “Turkish leaders have criticized the international order on open forums and called for a revision of its international architecture”56. Turkey’s global role was demonstrated by its ambition to promote regional integration in the Middle East as well as by Turkey’s stance in many conflicts in international institutions. The fact that the Turkish government championed Muslim sides in numerous conflicts even raised the question whether Turkey might be laying the ground for the creation of a “Muslim bloc”.57 In fact, Turkey’s foreign policy of promoting peaceful conflict resolution had already implied a “sub-text” according to which Turkey acts on behalf of other Muslim countries. Erdoğan’s rhetoric often hinted at such a role, for instance, when he defended Sudan’s president al-Baschir with the often-quoted statement that mass murder was something a Muslim would not be capable of.

Another case in point was the protest against the Mohammed caricatures in Danish newspapers and, subsequently, against the appointment of then-Danish Prime Minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen as NATO secretary general, justified by the alleged requests of Muslim nations for Turkey to use its veto. When AK Party leaders spoke of Prime Minister Erdoğan as being the representative of the “1.5 billion Muslims of the world”,58 it implied a claim to a global role for Turkey as representative of other Muslim states, equivalent to Brazil and South Africa’s claim to struggle for the “recognition of developing countries as full and equal partners”. In a similar vein, Turkey’s cooperation with Brazil in the UN Security Council to prevent the imposition of sanctions against Iran demonstrated Turkey’s self-conception as a “revisionist power” in regard to a “reconfiguration of the global governance institutions”.59

Domestic Rationales and International Repercussions of the Regional Power Role Concept

Many observers have interpreted this shift in the Turkish foreign policy role concept as a reaction to international change. For instance, former German Foreign Minister Fischer concluded in September 2011 that “the EU had slammed the door to EU membership in Turkey’s face; and this had led to a new orientation of Turkey”.60 However, the decisive move towards a different foreign policy concept occurred with the open confrontation towards Israel and the appeal to the “Arab masses” in May 2010, several years after the deterioration of relations with the EU in 2005 and before the Arab revolutions started in Tunisia in December 2010 and Islamist parties won the elections in Tunisia (October 2011), Morocco (November 2011) and Egypt (May 2012) which, to different degrees, have considered the example of the AK Party as a role model for a modern Islamic party.

Thus, it can be concluded that previous domestic change and the perspective of a new domestic hegemonic strategy played a significant role in triggering the shift in Turkey’s foreign policy role concept. First, the increasing self-confidence in Turkey’s growing economic strength as well as an emerging “domestic hegemony” allowed the AK Party government to discard the EU accession option. The downgrading of the military’s influence made the AK Party reconsider the role of military strength and the use of a nationalist discourse in foreign policy once both did no longer threaten the AK Party. Second, the regional power concept allowed the AK Party to move closer to its core electorate (stressing Turkey’s role for other “Muslim states“) and at the same time appeal to a nationalist electorate which had considered the concessions to the EU as excessive.

Subsequently, the new approach in Turkish foreign policy “paid significant dividends in the realm of domestic politics” in the years 2010 and 2011, such as the approval of constitutional changes by a large majority in the referendum in September 2010 despite its adamant rejection by the opposition (but still welcomed by the EU Commission) and the third consecutive election victory of the AK Party in June 2011. As Ziya Öniş commented, “nationalism of a different kind together with the traditional recourse to conservative-religious discourse constitutes the very tools to build the broad-based, cross-class electoral coalition”.61

However, the very claim of a regional power role (demonstrated by entering in permanent conflict with Israel and taking sides in the domestic conflicts of Iraq and Egypt and most explicitly by calling for regime change in Syria) has undermined its preconditions, primarily the consent within the regional environment. Turkey has lost the option to act as a mediator in these conflicts to foster the region’s stability. Hamas’ and in particular Iran’s politics (to ally itself with Assad in Syria) demonstrated that the support Turkey had lent them in the international arena was not reciprocated. Moreover, the support for Islamic parties and movements did not lead to regime change but jeopardized the recently established economic and diplomatic cooperation with Syria, Iraq and Iran and endangered the economic export model of the Anatolian “Islamic bourgeoisie”. It also opened up a “new front” in the Kurdish conflict, when Assad retorted by allowing for the emergence of an autonomous Kurdish area in the conflict-ridden Syria, thus increasing Turkey’s fear of an independent Kurdish state encompassing parts of Turkey, Iraq and Syria.

When regime change in Syria failed, Turkey’s open confrontation with Assad led to tangible tensions and possibly a new political-religious cleavage within the Middle East. The Turkish government started to feel it was facing a Shia-based coalition in Syria, Iran and an Iran-friendly Iraqi government. Iraqi Prime Minister Maliki heavily criticized Ankara’s Syria policy and Ankara’s close ties with the Iraqi Kurds. He openly accused the Turkish government of interfering in his country’s internal affairs and blocked Turkey from using his country as a trade route in an attempt to cut it off from the region at large. Following the Brotherhood’s ouster in Egypt, Turkish ties with the country have come almost undone, with the new leadership—taking issue with Ankara’s strongly pro-MB stance—withdrawing the Egyptian ambassador from Ankara. Turkish businesses have suffered in Egypt since then, undermining Turkey’s cherished soft-power goals. The TESEV study on the perception of Turkey in the Middle East of 2013 demonstrated that the support for Turkish foreign policy has declined in every single country of the Middle East. Turkey had ranked first in positive perceptions in 2011 and 2012 (with 78 and 69 per cent of respondents), however, it fell to fourth place in 2013 (with 59 per cent), and the number of respondents who agreed that Turkey engages in sectarian foreign policy increased within a year from 28 (2012) to 39 per cent (2013)62.

Conclusion

This essay has argued that the foreign policy role concept of the AK Party government shifted from the focus on cooperation and de-militarization and the Turkish bid for EU membership (coming close to a civilian power role concept) towards the ambition to shape the regional environment and to act as a global player and a representative of a group of states (coming close to a regional power role concept). After the AK Party government had started out with a co-operation and EU accession-oriented foreign policy (2002-2005), its attention shifted in reaction to the disappointment about the EU towards the Middle East. Although Turkish foreign policy became more assertive towards the EU and the US, it remained within the parameters of its foreign policy approach (2005-2010). It was from 2010 on that the domestic rationale and, subsequently, the Arab revolutions led the AK Party to shift towards a regional power role concept. Although Turkey’s role was rather interpreted as that of a “central country” by Turkish policy makers, it followed the ideal type of a regional power in the pursuit of a regional project in the Middle East.

When regime change in Syria failed, Turkey’s open confrontation with Assad led to tangible tensions and possibly a new political-religious cleavage within the Middle East

This is not to deny the serious challenges Turkey’s foreign policy started to face, for instance in Syria; however, it has been demonstrated that its answers were based on a change in the foreign policy role concept. Similar to regional powers such as Brazil or South Africa, Turkey started to combine a revisionist position in international organizations with the claim to be the representative of a group of (Muslim) states. Moreover, Turkish foreign policy clearly departed from the role of a civilian power as the pursuit of its regional project implied open confrontation towards Israel and taking sides in the domestic conflicts of its neighbor states. The mutual withdrawal of ambassadors from Israel, Syria and Egypt finally left Turkey without the option to act as “mediator” in the conflicts in the region.

The essay has further argued that the change of foreign policy roles was also related to different functions in the domestic context. The AK Party government’s emphasis on de-militarization and EU accession was instrumental in the struggle against the Kemalist elite and military. In contrast, the adoption of a regional power role concept strengthened the hegemonic position of the AK Party in Turkish society in the years 2010 and 2011. However, its repercussions have started to undermine Turkey’s “soft power”, as demonstrated by the changing perceptions of Turkey in the Middle East, and may in the long run also undermine Turkey’s economic position. Finally, this essay has argued against a conception of continuity in Turkish foreign policy, constructed “in hindsight” (both by advocates and adversaries of the current AK Party government policies), which prevents a debate of the changes which have occurred and the possibility to re-evaluate the merits of different foreign policy choices.

Endnotes

- Kemal Kirişci, “The Transformation of Turkish Foreign Policy: The Rise of the Trading State,” New Perspectives on Turkey, Vol. 40 (2009), pp. 29-57.

- William Hale and Ergun Özbudun, Islamism, Democracy and Liberalism in Turkey: The Case of the AK PARTY (London: Routledge, 2010).

- See Saban Kardas, “From Zero Problems to Leading the Change: Making Sense of Transformation in Turkey’s Regional Policy,” Turkish Foreign Policy Briefs, TEPAV, (2012).

- See the contributions in Turkish Studies no. 4, 2013.

- “Turkey and the Middle-East – Ambitions and Constraints,” International Crisis Group, Europe Report, No. 203, (April 7, 2010).

- Soner Cagaptay, “Ankara’s Middle East Policy Post Arab Spring,” Policy Notes, The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, No. 16, November 2013.

- The Economist, 8 June 2013.

- Hale and Özbudun, Islamism, Democracy and Liberalism in Turkey, p. 134.

- Ziya Öniş, “The Triumph of Conservative Globalism: The Political Economy of the AK PARTY Era”, Turkish Studies, Vol. 13, No. 2 (2012), pp. 135-152.

- http://www.mfa.gov.tr/policy-of-zero-problems-with-our-neighbors.en.mfa.

- Detlef Nolte, “How to Compare Regional Powers: Analytical Concepts and Research Topics,” Review of International Studies, 36, pp. 881-901.

- Soner Cagaptay, “Ankara’s Middle East Policy Post Arab Spring,” p. 7.

- Ramazan Kilinc, “Turkey and the Alliance of Civilizations: Norm Adoption as a Survival Strategy”, Insight Turkey, Vol. 11, No. 3, (2009), pp. 57-75, p. 62.

- Saban Kardaş, “From Zero Problems to Leading the Change.”

- Max Weber, “Objectivity in Social Science and Social Policy” in The Methodology of the Social Sciences, E. A. Shils and H. A. Finch (ed. and trans.), (New York: Free Press).

- The aim of the essay is not to criticise the policy development but to underline the dimensions of change implied.

- Hanns Maull, “Germany and Japan: The New Civilian Powers,” Foreign Affairs, Vol. 69, No. 5 (1990), pp. 91-106.

- Hanns Maull, “Germany and the Art of Coalition Building,” European Integration, Vol. 30, No. 1 (2008), pp. 131–152.

- Maull, “Germany and Japan”, p. 92.

- Tanja Börzel and Thomas Risse, “The Transformative Power of Europe: The European Union and the Diffusion of Ideas,” KFG working paper, 01 (May, 2009).

- Ian Manners, “Normative Power Europe Reconsidered: Beyond the Crossroads,” Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 13, No. 2, 2006, pp. 182-199.

- Thomas Berger, “Norms, Identity and National Security in Germany and Japan,” in: Peter Katzenstein (ed): The Culture of National Security: Norms and Identity in World Politics New Directions in World Politics, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996).

- Hanns Maull, “Germany and the Art of Coalition Building,” pp. 131–152.

- Berger, “Norms, Identity and National Security in Germany and Japan,” p. 331.

- Derrick Frazier and Robert Stewart-Ingersoll: “Regional Powers and Security: A Framework for Understanding Order within Regional Security Complexes,” European Journal of International Relations, Vol. 16, No. 4 (2010), pp. 731-753.

- Nolte, “Macht und Machthierarchien in den internationalen Beziehungen.”

- Nolte, ibid., p. 8.

- Nolte, ibid.,p. 895.

- Robert Kappel, R. “The Challenge to Europe: Regional Powers and the Shifting of the Global Order,” Intereconomics, Vol. 5 (2011), pp. 275-286.

- D. Flemes, “Conceptualising Regional Power in International Relations: Lessons from the South African Case,” GIGA Working Paper, No. 53 (2007), Hamburg.

- Flemes, ibid.

- Kemal Kirişci, “Turkey’s Foreign Policy in Turbulent Times,” Chaillot Papers, 92 (2006), Paris: EU-ISS.

- Ziya Öniş, “The Triumph of Conservative Globalism: The Political Economy of the AK PARTY era,” Turkish Studies, Vol. 13, No. 2 (2012), pp. 135-152.

- Hale and Özbudun, Islamism, Democracy and Liberalism in Turkey, p. 120.

- http://sam.gov.tr/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/SukruElekdag.pdf.

- Saban Kardaş, “From Zero Problems to Leading the Change.”

- Hale and Özbudun, Islamism, Democracy and Liberalism in Turkey, pp. 110-120.

- Official Statistics of the Turkish Government; http://www.invest.gov.tr/EN-US/INVESTMENTGUIDE/INVESTORSGUIDE/Pages/FDIinTurkey.aspx; accessed 28.9.2011

- Kirişci, “The Transformation of Turkish Foreign Policy: The Rise of the Trading State.”

- Ziya Öniş and Suhnaz Yilmaz, “Between Europeanisation and Euro-Asianism: Foreign Policy Activism in Turkey During the AKP era”, Turkish Studies, Vol. 19, No. 1 (2009), pp. 7-24, p. 12

- Resat Bayer and Fuat Keyman, “Turkey: An Emerging Hub of Globalization and Internationalist Humanitarian Actor?,” Turkish Studies, Vol. 12, No. 1(2012), pp. 73-90.

- Öniş and Yilmaz, “Between Europeanisation and Euro-Asianism,” p. 9.

- Kilinc, “Turkey and the Alliance of Civilizations”, p. 62.

- Öniş and Yilmaz, “Between Europeanisation and Euro-Asianism,” p. 19.

- This is not the place to debate whether the changes in the EU foreign and security policy demonstrated its character as a “normative power” or the return to classic interventionism.

- Hürriyet, July 13, 2011.

- Today’s Zaman, September 15, 2011.

- Meliha Altunişik, “The Turkish Model and Democratization in the Middle East”, Arab Studies Quarterly, Vol. 27, No. 1-2, (2005), p. 56.

- Saban Kardaş: “Turkey: A Regional Power Facing a Changing International System”, Turkish Studies, Vol. 14, No. 4 (2013), pp. 637- 660.

- Kemal Kirişci, “Turkey’s Engagement with its Neighborhood: A Synthetic and Multidimensional Look at Turkey’s Foreign Policy Transformation”, Turkish Studies, Vol. 13, No. 3 (2012), pp. 319-341.

- Kirişci, “Turkey’s Engagement With its Neighborhood”, p. 321.

- Ibid, p. 322.

- 2011 displays a significant rise in absolute figures which still has to be converted in per cent of GDP. See http://milexdata.sipri.org/. However, the figures for 2009 and 2010 are also both higher than the all-time low figures for 2007 and 2008.

- Joseph S. Nye, Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics (New York: International Affairs, 2004).

- Quotes from Bülent Aras and A. Görener “National Role Conceptions and Foreign Policy Orientation”, Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies, No. 12, Vol. 1 (March 2010), pp. 73-92.

- Kardaş, “Turkey: A Regional Power”, p. 652.

- “Turkey and the Middle-East – Ambitions and Constraints.”

- “Turkey and the Middle-East – Ambitions and Constraints,” p. 7.

- Nolte, “How to Compare Regional Powers”, p. 900.

- Joschka Fischer, “Starker Mann am Bosperus. Ein Gastbeitrag”, Sueddeutsche Zeitung, October 10, 2011.

- Öniş, “The Triumph of Conservative Globalism,” pp. 136-138.

- Mensur Akgün and Sabiha Senyücel Gündoğar, “The Perception of Turkey in the Middle East 2013,” TESEV Publications, January 2014, Istanbul.