┬Ā

Introduction: The Legacy of Muammar Qaddafi and the Damage Done by His Would-be Successor

┬Ā

Muammar Qaddafi ruled Libya (badly) with an iron fist for 42 years, creating a grotesque system of governance that combined personality cult, Islam, and communist political structures. The result was a degradation of good citizenship and rotten institutions ŌĆōespecially the security services. Despite the nostalgia that French Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian has for Qaddafi,1 globalization and advances in communication meant it was inevitable that Libyans, fed up with his 42 years of brutality and oppression,2 would rise up. When Qaddafi launched a campaign to slaughter the people of Benghazi, it was France under President Nicholas Sarkozy ŌłÆdespite his previous insouciance and economic interestsŌłÆ who took the first concrete steps to stop it.3 Libyan appreciation for FranceŌĆÖs role was evident in the large notice board that greeted travelers arriving at Benghazi airport.

Unfortunately, as then U.S. President Barack Obama4 and the UK House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee5 noted, the international community failed to appreciate the urgency of LibyaŌĆÖs plight and allocate the necessary resources to bring stability to Libya after the Revolution and the situation deteriorated.

Khalifa Haftar was an officer in King IdrisŌĆÖ army and had been a commander under Qaddafi from the time he seized power in 1969. After Haftar was defeated by French forces in Chad in 1989, Qaddafi disowned him and he was taken over by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) as an agent in their conflict with Qaddafi.6 Returning from exile in the United States in 2011, he wanted to command the revolutionary forces, but could only get Commander of the land forces7 (effectively the third highest post). In February 2014, he called for suspension of the General National Congress and the government in a failed coup attempt.8 He then led a coalition of army units, former revolutionary groups and tribal militias calling themselves the ŌĆ£Libyan National ArmyŌĆØ9 (LNA) in a series of attacks, presented as Operation Karama (Dignity), against not only the radical group Ansar al-Sharia in Benghazi but also officially recognized units, funded and nominally under the command of the Chief of General Staff. While claiming to serve the government based in Tobruk, Haftar has established a kind of military mini-state where he is the supreme authority and where rights and freedoms have gradually diminished.

Macron and Le Drian have taken up with some odd bedfellows, starting with the regional autocracies: Saudi Arabia, Egypt and the UAE.┬Ā They seem an odd fit with MacronŌĆÖs supposed ŌĆ£feminist foreign policyŌĆØ

With the Libyan Political Agreement negotiated by the UN on December 17, 2015, a Government of National Accord (GNA) was formed, recognized by the entire international community including all of the permanent members of the UN Security Council and the countries of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Haftar did everything he could to prevent its implementation. The chaos that followed gave the so-called ŌĆ£Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS)ŌĆØ10 an opportunity to gain a foothold, especially in Sirte.11 Haftar defeated the extremist group Ansar al-Sharia in Benghazi, while destroying much of the city. He used this as his calling card to portray himself the ŌĆ£great fighter of the Islamic terrorists,ŌĆØ12 yet others fought the greatest battles. Local Salafists drove ISIS from Derna in 201513 and then routed it from Sabratha along with other anti-Haftar elements and the help of U.S. airstrikes.14 The battle for Sirte was won by the GNAŌĆÖs Bunyan Marsous (ŌĆ£Solid WallŌĆØ) operation ŌłÆcomposed mainly of fighters from Misrata and small contingents from other townsŌłÆ supported by U.S. and UK intelligence and logistics,15 special forces and air support.16 Six hundred and fifty GNA fighters gave their lives and 2,000 were wounded.17 While GNA forces fought ISIS, Haftar took control of the oil fields and bought the loyalty of certain tribal militias in the south. The United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) continued to mediate and a national conference was scheduled for April 2019.18 A few days before it was to start, Haftar launched a major offensive on Tripoli. One year later, UNSMIL described the impact of this offensive:19

┬Ā

Humanitarian Situation Deteriorated to Unprecedented Levels

- At least 685 civilian casualties (356 deaths and 329 injured)

- 149,000 people in and around Tripoli forced to flee their homes

- Over 345,000 civilians remain in frontline areas

- Additional 749,000 people in areas affected by the clashes

- 893,000 people in need of humanitarian assistance

- Appalling impact in terms of damage to and destruction of homes, hospitals, schools and detention facilities

- Human rights violations have exponentially increased with┬Āattacks against human rights defenders and journalists, doctors, lawyers and judges, migrants and refugees, and deteriorating conditions of detention.┬Ā

Economic Collapse

- Over 100 billion Libyan Dinars (LYD) in domestically held debt ($73.4 billion)

- Another $1 billion credit lines for domestic fuel imports

- LYD 169 billion ($124.1 billion) outstanding contractual obligations

- Oil blockade imposed January 17, 2020 already resulted in financial losses exceeding $4 billion

- Spending diverted to war effort destroying rather than building critical infrastructure

- Two separate central banks prevented monetary or fiscal policy reform and contributed to a domestic banking crisis.

All of the above problems have been compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic.20

HaftarŌĆÖs French-backed campaign caused more hardships for women and children, as well as a higher likelihood of sexual violence.21 Member of Parliament Siham Sergewa was kidnapped from her home in Benghazi by an armed group22 and we still have no news of her fate.23 On April 27, 2020 ŌłÆfollowing another 248 civilian casualties largely due to his forcesŌłÆ Haftar claimed to have a mandate to take over all government in Libya, removing whatever small legitimacy he had claimed from his association with the House of Representatives.24

Sheikh al-Madkhali is strongly opposed to the Muslim Brotherhood.┬Ā Many of HaftarŌĆÖs Libyan fighters subscribe to this doctrine and have a history of enforcing ever stricter social mores when they take over a region

┬Ā

A woman holds a placard reading in French ŌĆ£Thank you very much FranceŌĆØ during a rally calling for the imposition of a no-fly zone in Benghazi in Eastern Libya on March 12, 2011. By contrast 8 years later in Western Libya, a message rejecting French President Macron is displayed during a demonstration with yellow vests against strongman Khalifa Haftar in┬Ā Tripoli on April 19, 2019. Getty Images

A woman holds a placard reading in French ŌĆ£Thank you very much FranceŌĆØ during a rally calling for the imposition of a no-fly zone in Benghazi in Eastern Libya on March 12, 2011. By contrast 8 years later in Western Libya, a message rejecting French President Macron is displayed during a demonstration with yellow vests against strongman Khalifa Haftar in┬Ā Tripoli on April 19, 2019. Getty Images

┬Ā

┬Ā

The Friends of Haftar Club

┬Ā

The Macron government appears to have a fear of Islam. It recently instigated a controversial campaign at home against ŌĆ£Islamic separatism.ŌĆØ25 Nonetheless, in their foreign campaign against ŌĆ£Islamic terrorismŌĆØ26 and ŌĆ£political Islam,ŌĆØ27 Macron and Le Drian have taken up with some odd bedfellows, starting with the regional autocracies: Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and the UAE.28 They seem an odd fit with MacronŌĆÖs supposed ŌĆ£feminist foreign policy.ŌĆØ

┬Ā

Saudi Arabia

Under Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman, Saudi Arabia has gone from being a calming force in the region to a destabilizer. Its legal system is based on Sharia law. In 2018, the regime murdered a journalist abroad29 and has developed a very bad reputation for human rights,30 despite expensive efforts to whitewash its reputation.31 Saudi interests have bought into newspapers owned by Russian oligarch and former KGB32 officer Alexander Lebedev and his son Evgeny, which include the London Evening Standard and the Independent.33 Alexander is sometimes critical of the Russian government but has also provided support for controversial moves like the annexation of Crimea.34 Women are required to cover themselves completely. Despite now having the right to drive, those who had petitioned for this right have gone to jail, including a royal princess.35 In protest of Saudi ArabiaŌĆÖs treatment of women and other human rights abuses, activists have discouraged governments from attending a November 2020 G20 summit hosted by Saudi Arabia.36 Following the problems caused by al-Qaida37 abroad and at home, some of the countryŌĆÖs leadership started supporting a different strain of conservative (quietist) Sunni Islam with less potential to be a threat to the regime than the classic Wahabi school. One of Saudi ArabiaŌĆÖs main contributions to Haftar has been the ideological support of the Madkhali Salafists.38 While still preaching extremely conservative Islam, this line of thought also says not to question secular leaders, a very convenient notion for princes and strongmen.

Sheikh al-Madkhali is strongly opposed to the Muslim Brotherhood.39 Many of HaftarŌĆÖs Libyan fighters subscribe to this doctrine and have a history of enforcing ever stricter social mores when they take over a region.40 They also have followers among the GNA, causing some to fear a ŌĆ£5th ColumnŌĆØ that could join Haftar or form another ultra-conservative regime.41 Besides ideology, Saudi Arabia has helped Haftar by lobbying Washington,42 financing,43 and possibly paying for Russian mercenaries.44 Both the U.S. Congress45 and the European Parliament have pushed to block arms sales to the Kingdom.46 In 2019, a UK Court of Appeal ruled arms sales to Saudi Arabia illegal because the British Government had not adequately considered accusations of violations of international humanitarian law.47 As the UK seeks to renew sales, activists are again taking the case to court.48

With the help of his backers and former Qaddafi officers, Haftar has recruited thousands of African mercenaries, including Janjaweed and diverse paramilitary and rebel groups, offering $ 3,000 plus vehicles and plunder

┬Ā

The UAE

The UAE is Saudi ArabiaŌĆÖs main ally in the brutal Yemen conflict that has displaced 6.65 million and put 24.3 million people in need.49 Though more modern than Saudi Arabia, Sharia remains an important source of law. For example, women who have extra-marital relationships go to jail. Currently, there are reported to be a number of foreign female workers stuck in the UAE for this reason: the prisons will not take them because of COVID-19 but they are not allowed to leave until they serve their sentence. In the meantime, they and their children are in a precarious situation.50 However, it is not only poor women who have issues. A UK family court judgement found that that the emir of Dubai (also Vice-President and Prime Minister of the UAE) orchestrated the abductions of two of his daughters and subjected his youngest wife to a campaign of ŌĆ£intimidation.ŌĆØ51 Though the UAE provided little help to Libya after the Revolution, it has been accused of arming Tubu tribal militias in the south since 2012.52 An early and important backer of HaftarŌĆÖs attempt to seize power, the UAE furnished financing and weapons and even carried out attacks using its own forces and weapons systems.53 It also paid for a number of mercenary forces to assist.54 Like Saudi Arabia, the UAE used its lobbying prowess to assist Haftar with the Trump Administration55 and attempted to control media in Libya.56 It deeply compromised the credibility of the United Nations by secretly hiring Bernardino L├®on, the head of UNSMIL, as the highly remunerated director of its diplomatic academy while he was still leading negotiations.57 There are members of the U.S. Congress who feel the U.S. should cut off arms sales.58

┬Ā

Egypt

Egypt is still a fairly conservative country where Sharia remains an important source of law.59 Recently, President el-Sisi has attempted to exert more control over religious authorities to serve his own interests.60 As head of the armed forces, he seized power in a coup against democratically elected President Mohammed Morsi from the Muslim Brotherhood following the Arab Spring.61 Some evidence purports to show that the UAE helped.62 A week after the coup, the UAE and Saudi Arabia gave $8 billion to the new regime63 and have continued to provide substantial financing ever since.64 Much of this has helped pay for a massive increase in weapons purchases from France, which will be discussed in greater detail below. This financing has not been without cost, since EgyptŌĆÖs funders have expected to exercise a certain control over its affairs.65 Egypt gave two islands to Saudi Arabia66 and used its influence to block a motion to have the Saudi branch of ISIS added to a UN list of terrorist groups.67 Under President el-SisiŌĆÖs leadership, Egypt has enthusiastically supported Haftar with weapons, air strikes, and fuel smuggling despite theoretically supporting the GNA.68 While paying lip service to peace negotiations, Egyptian materiel was simultaneously reported as on its way to Haftar when he began his assault days before the national dialogue was to begin69 and it also lobbied the Trump Administration on HaftarŌĆÖs behalf.70 While some of its air strikes purported to strike ISIS in response to attacks on Egyptian Coptic Christians living in Libya, they actually hit Libyan Salafists unrelated to the attacks but opposed to Haftar ŌłÆthe very ones who had forced ISIS out of Derna.71 EgyptŌĆÖs bad human rights record has not stopped France from cozying up to it,72 but it has led to calls by many in the U.S. to slash military aid after an American citizen was killed in prison there.73

┬Ā

Russia

Egypt has also been accused of housing Russian Special Forces74 and possibly other support elements aiding HaftarŌĆÖs campaign. From the beginning, Russia has tried to pretend to be neutral while providing material support for Haftar in the form of weapons systems, printing bank notes, and diplomatic cover.75 When HaftarŌĆÖs offensive on Tripoli stalled, reports appeared of 1,200 Russian mercenaries76 working for the Wagner Group, providing critical skills and eventually provoking TurkeyŌĆÖs direct military engagement.77 These are similar to the fighters Russia sent to eastern Ukraine.78 Like the MENA autocracies, Moscow did not want a liberal democracy on its doorstep. In Libya, they have been accused of indiscriminately planting land mines leading to unnecessary civilian casualties.79 Russia is also alleged to have provided technicians, aircraft80 and air defense81 to support the Wagner mercenaries. This ally regularly conducts cyber-attacks in Europe and the rest of the world82 and is accused of trying to assassinate its critics,83 including women.84

┬Ā

Ethnic Mercenaries

With the help of his backers and former Qaddafi officers, Haftar has recruited thousands of African mercenaries, including Janjaweed and diverse paramilitary and rebel groups, offering $ 3,000 plus vehicles and plunder.85 To a lesser extent, the GNA and/or other anti-Haftar groups have recruited some of their own fighters, mostly from Tubu groups along the border ŌłÆbut at times they are alleged to have tried to buy off some of HaftarŌĆÖs mercenaries.86 The Chadians and Sudanese are reputed to be good desert fighters: cheaper and more willing to work away from home. Besides money, they may have other motives like supporting their ethnic kin, trafficking, theft and other commercial interests.87 Groups have supported several factions as the situation or their motivations shifted.88 Brutal attacks by HaftarŌĆÖs forces on Tubu communities have been particularly motivating.89 The presence of these mercenaries not only helps sustain the Libyan conflict, it also destabilizes the region, which in turn creates more refugees.90 Libyans of the same ethnicity as the mercenaries risk finding themselves identified as foreign fighters.

France risks being frozen out, though it might hope that the regional autocracies would remember its efforts when making weapons purchases and other contracts

┬Ā

┬Ā

ŌĆ£La France Perfide?ŌĆØ

┬Ā

While Macron rails against Turkey for supporting the internationally recognized government of Libya against a rogue warlord accused of crimes against humanity, France has been actively assisting Haftar with special forces since at least early 2016.91 According to Haftar himself, ŌĆ£France helped (his cause) like no other countryŌĆ”providing information, military reconnaissance and security experts, which helped a lot.ŌĆØ92 Previously unacknowledged, this became overt when three French commandos were killed in July of 2016.93 The French advisers were accompanying Haftar forces fighting the local groups combating ISIS. Their presence already indicated to many in the international community that France was keen to undermine the internationally recognized government in favor of a warlord. Apparently, mounting attacks against those actually fighting against ISIS is part of MacronŌĆÖs surreal anti-terrorist strategy. Under the direction of FranceŌĆÖs Directorate-General for External Security94 (DGSE), France has also employed mercenary outfits to aid Haftar with tasks such as crucial intelligence gathering,95 notably against the local Islamists who drove ISIS out of Derna.96 At the same time that France was assisting Haftar, the French-led Operation Barkhane has been accused by the UN Panel of Experts of refusing to share information with them.97 In 2019, U.S. Javelin missiles sold to France for use in Afghanistan were found in a Haftar camp captured by the GNA.98

An interview with MacronŌĆÖs Foreign Minister Le Drian after Haftar launched his offensive on Tripoli makes clear that the French government had no interest in a political solution.99 Macron has also used FranceŌĆÖs important positions in international organizations to shelter Haftar and stymie political discussions that might allow Libya to get out of its crisis in a more peaceful and sustainable way. In April 2019, France blocked an EU statement100 condemning HaftarŌĆÖs assault and teamed up with Russia to block a resolution calling for a ceasefire at the UN Security Council.101 There has also been controversy over the EUŌĆÖs ŌĆ£Operation IriniŌĆØ (Eunavfor Med Irini) in the Mediterranean, which seeks to block weapons delivery by sea to Libya (i.e. mostly those going to the GNA) while doing nothing about all those shipped by its clients to Haftar by air or via Egypt.102 Related to that, there was an issue at NATO when France accused a Turkish frigate of harassing a French one trying to intercept a ship possibly carrying weapons to the GNA. Though the official NATO report was inconclusive, France quit Operation Sea Guardian in protest.103

┬Ā

Refugees

One of President MacronŌĆÖs reasons for supporting Haftar is that he believes the strongman will stop a flood of refugees washing up on the shores of the European Union. In this context, his hostility toward Turkey can only be explained as the complex of one who resents the person who does them a favor. Turkey is by far the country housing the worldŌĆÖs largest refugee population, 3.6 million of whom are Syrians under temporary protection and close to 370,000 of which are refugees and asylum seekers of other nationalities.104 This is more than all the refugee populations of European Union member states combined (2,591,349).105 Among MacronŌĆÖs autocratic friends: Egypt hosts about 258,816,106 the UAE 1,247107 and Saudi Arabia 320.108 Saudi Arabia has agreed to allow some workers to continue their stay.109 France itself hosts around 407,923 refugees.110

Though the behavior of President Macron and his government may seem hypocritical and somewhat inspired by hysterical emotion, there are certain elements of commercial, short-term logic to it

┬Ā

Blood Money

What else can explain Macron and Le DrianŌĆÖs obsession with supporting Haftar? The most obvious and quantifiable explanation is the increasingly large number of weapons that France sells to autocracies in the MENA region. Given the misery, economic damage and ensuing flow of refugees that these have been causing, one might be forgiven for thinking this a short-sighted approach. However, one can understand the ŌĆ£apr├©s moi le d├®lugeŌĆØ attitude (i.e. a problem for the next guy) since other major arms exporters exhibit a similar approach. Not only do these sales bring in billions worth of profits, they also help pay for the fixed costs of developing weapons systems for oneŌĆÖs own national security forces and mean that a country is less dependent on the goodwill of a foreign supplier. During the Cold War, there was more coordination between NATO allies about what to sell to certain countries, but subsequently, national commercial interests have predominated.111 They rarely worry that these arms could be used against them. Libya is a case in point. After France sold Mirages to the Qaddafi regime in the early Seventies, it ended up fighting several wars against it in the eighties in support of Chad ŌłÆwhere Haftar was the losing Libyan commander, no less.

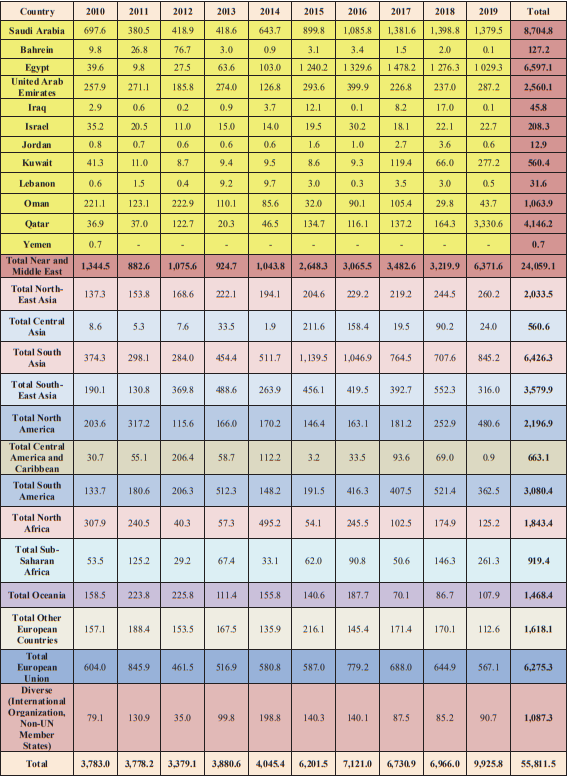

Table 1, taken from Annex 9 of the official government report on French arms exports from 2010-2019,112 gives probably the most substantive and convincing reason behind FranceŌĆÖs recent enthusiasm for Haftar and his autocratic backers. The Near and Middle East represents almost half of FranceŌĆÖs total arms sales, which have been increasing exponentially over the last ten years. Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the UAE are all among FranceŌĆÖs biggest clients, each individually bigger than most other regions. The only other countries in the same league are India and Qatar. To further illustrate, Egypt and Saudi Arabia both bought more weapons from France last year than the rest of the European Union combined. Whether it wants to admit it or not, France has a powerful motivation to adopt the point of view of these important customers, which already feeds into some of its biases. If arms sales generate more chaos, then that will create more demand. The Macron government may even be tempted to throw in other services like training, information gathering, intelligence and the use of its vote in the Security Council and the EU. In 2009, France built its first new foreign base since the colonial period in Abu Dhabi, ostensibly to extend its strategic reach but also to help sell more weapons.113 Of course, the more France invests in this strategy, the more it will be tempted to double down, even when this may be a losing proposition. If Haftar wins, then it feels its oil investments will be secure and Haftar has promised big contracts for infrastructure114 plus, undoubtedly, more weapons sales. If its ŌĆ£championŌĆØ loses, then France risks being frozen out, though it might hope that the regional autocracies would remember its efforts when making weapons purchases and other contracts.

┬Ā

Table 1: Details of Equipment Delivered Since 2010 by Country and Regional Breakdown (in Millions of Current Ōé¼, 2010-2019)

Source: French Ministry of Armed Forces

Despite the criticisms of French arms sales to these countries by institutions like the European Parliament,115 Amnesty International116 and Human Rights Watch,117 President Macron probably feels that because he has a female defense minister in charge of these transactions (Florence Parly), that they are consistent with a ŌĆ£feminist foreign policy.ŌĆØ

┬Ā

┬Ā

Conclusion

┬Ā

France has based its fervent support for Libyan warlord Khalifa Haftar in the name of fighting Islamic terrorism, which it conflates with political Islam. While claiming to pursue a ŌĆ£feminist foreign policy,ŌĆØ it has ignored the many crimes against humanity attributed to HaftarŌĆÖs coalition and the repressive policies of his international backers. It also seeks to minimize the numbers of refugees coming to Europe. Though somehow resentful towards Turkey for hosting millions that might otherwise come to France, it seems oblivious to the way its own actions help create the conditions that produce refugees. Though the behavior of President Macron and his government may seem hypocritical and somewhat inspired by hysterical emotion, there are certain elements of commercial, short-term logic to it; notably, the sale of weapons. Unfortunately, besides the destruction of its credibility, FranceŌĆÖs policies will likely cause harm not only to Africa and the Middle East, which they are doing already, but also to France and Europe.

┬Ā

┬Ā

Endnotes

┬Ā

1. Paul Taylor, ŌĆ£FranceŌĆÖs Double Game in Libya: In Backing a Warlord, Paris May Be Dealing Itself a Losing Hand,ŌĆØ Politico, (April 19, 2019).

2. Dirk Vandewalle, A History of Modern Libya, 2nd Edition, (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

3. Bernard-Henri L├®vy, La Guerre Sans LŌĆÖaimer: Journal dŌĆÖun ├ēcrivain au C┼ōur du Printemps Libyen, (Grasset, 2011).

4. ŌĆ£Remarks by President Obama to the United Nations General Assembly,ŌĆØ The White House Office of the Press Secretary, (September 28, 2015).

5. Crispin Blunt, ŌĆ£Government ŌĆśUnwillingŌĆÖ to Learn the Lessons of Libya Interventions,ŌĆØ UK House of Commons, (November 25, 2016).

6. Acil Tabbara, ŌĆ£Le Mar├®chal Haftar, ├ēmule de Kadhafi?,ŌĆØ LŌĆÖOrient-Le Jour, (February 17, 2018); J├®r├┤me Tubiana and Claudio Gramizzi, ŌĆ£Lost in Trans-Nation: Tubu and Other Armed Groups and Smugglers along LibyaŌĆÖs Southern Border,ŌĆØ Small Arms Survey, (December 2018).

7. Mark Urban, ŌĆ£The Task of Forming a more Effective Anti-Gaddafi Army,ŌĆØ BBC News, (April 15, 2011).

8. ŌĆ£Attempted Coup dŌĆÖ├®tat in Libya,ŌĆØ Voltaire Network, (February 15, 2014); ŌĆ£S/2015/128 - Final Report of the Panel of Experts on Libya Established Pursuant to Security Council Resolution 1973 (2011),ŌĆØUnited Nations, Distr. General, (February 23, 2015), Paragraph 32; ŌĆ£Libya Major General Khalifa Haftar Claims GovŌĆÖt Suspended in Apparent Coup Bid; PM Insists Tripoli ŌĆśUnder Control,ŌĆÖŌĆØ CBS News, (February 14, 2014).

9. Also referred to as the ŌĆ£Libyan Arab Armed ForcesŌĆØ (LAAF) or in the parlance of the UN Panel of Experts on Libya: Haftar Armed Forces (HAF).

10. The group is also commonly referred to as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), which is way it is usually referred to in United Nations documents, as well as the Islamic State (IS) or ŌĆ£DaeshŌĆØ in Arabic (sometimes spelled ŌĆ£DaechŌĆØ with a c instead of an s).

11. Dan De Luce, ŌĆ£Why Libya MattersŌĆöAgain: The Islamic State Is Gaining Ground in LibyaŌĆÖs Chaotic Vacuum and Western Governments Are Worried,ŌĆØ Foreign Policy, (February 12, 2016).

12. Against this background, Haftar was able to gain a political role and the legitimacy such role requires by presenting himself as the leader in fighting Islamic terrorism and the emergence of radical groups in Libya. See Karim Mezran, and Arturo Varvelli, ŌĆ£Libyan Crisis: International Actors at PlayŌĆØ in Karim Mezranv and Arturo Varvelli (eds), Foreign Actors in LibyaŌĆÖs Crisis, (Atlantic Council and Italian Institute for International Political Studies (ISPI), 2017), p. 16. Indeed, it is this image of Haftar as a fighter of ŌĆ£Islamic terrorismŌĆØ that the UAE and Saudi Arabia were able to sell to President Trump and which led to his dubious praise for Haftar even after he had started his advance on Tripoli days before the Libyan peace conference was due to begin in April 2019. Though he did not officially endorse the offensive as such, in the phone call he had with Haftar, it was reported that Trump ŌĆ£recognised Field Marshal HaftarŌĆÖs significant role in fighting terrorism and securing LibyaŌĆÖs oil resources, and the two discussed a shared vision for LibyaŌĆÖs transition to a stable, democratic political system.ŌĆØ See, ŌĆ£Trump Discussed ŌĆśShared VisionŌĆÖ in Phone Call to Libyan Warlord Haftar,ŌĆØ France 24, (April 19, 2019).

13. Mary Fitzgerald and Mattia Toaldo, ŌĆ£A Quick Guide to LibyaŌĆÖs Main Players,ŌĆØ European Council on Foreign Relations, (December 2016).

14. ŌĆ£S/2018/140-United Nations Support Mission in Libya Report of the Secretary-General,ŌĆØ United Nations Security Council, (February 12, 2018), Paragraph 14; ŌĆ£A Quick Guide to LibyaŌĆÖs Main Players; Christopher M. Blanchard and Carla E. Humud, ŌĆ£The Islamic State and U.S. Policy,ŌĆØ US Congressional Research Service, (January 18, 2017), p. 22.

15. Emma Graham-Harrison and Chris Stephen, ŌĆ£Libyan Forces Claim Sirte Port Captured from ISIS as Street Battles Rage,ŌĆØ The Guardian, (June 11, 2016); Tom Westcott and Mark Hookham, ŌĆ£SAS Blasts ISIS with ŌĆśPunisherŌĆÖ in Libya,ŌĆØ The Sunday Times, (August 7, 2016); Missy Ryan and Sudarsan Raghavan, ŌĆ£U.S. Special Operations troops aiding Libyan Forces in Major Battle against Islamic State,ŌĆØ The Washington Post, (August 9, 2016). It is possible that the UK forces included participation from Jordanian Special Forces as well. See, Rori Donaghy, ŌĆ£Revealed: Britain and JordanŌĆÖs Secret War in Libya,ŌĆØ Middle East Eye, (March 25, 2016).

16. ŌĆ£AFRICOM Concludes Operation Odyssey Lightning,ŌĆØ United States Africa Command, (December 2, 2016).

17. ŌĆ£S/2016/1011-United Nations Support Mission in Libya Report of the Secretary-General,ŌĆØ United Nations Security Council, (December 01, 2016), Paragraphs 22-25.

18. ŌĆ£S/2019/19-United Nations Support Mission in Libya Report of the Secretary-General,ŌĆØ United Nations Security Council, (January 7, 2019), Paragraph 74.

19. ŌĆ£One Year of Destructive War in Libya, UNSMIL Renews Calls for Immediate Cessation of Hostilities and Unity to Combat COVID-19,ŌĆØ UNSMIL, (April 4, 2020).

20. Because of the conflict, according to a survey by the World Health Organization (WHO), while 75 percent of primary health centers are open, only 20 percent are delivering services. See, ŌĆ£Acting SRSG Stephanie Williams Briefing to the Security Council,ŌĆØ UNSMIL, (May 19, 2020).

21. ŌĆ£S/2018/140,ŌĆØ Paragraphs 50 and 81; ŌĆ£S/2019/682-United Nations Support Mission in Libya Report of the Secretary-General,ŌĆØ United Nations Security Council, (August 26, 2019). Paragraphs 57-58; ŌĆ£S/2020/41-United Nations Support Mission in Libya Report of the Secretary-General,ŌĆØ United Nations Security Council, (January 15, 2020), Paragraph 54.

22. ŌĆ£S/2019/682,ŌĆØ Paragraph 57.

23. ŌĆ£S/2020/41,ŌĆØ Paragraph 54.

24. ŌĆ£Acting SRSG Stephanie Williams Briefing to the Security Council.ŌĆØ

25. Karina Piser, ŌĆ£Macron Wants to Start an Islamic Revolution: The French President is Planning to Curb the Influence of Extremist ClericsŌĆöBut His Critics See Something More Sinister,ŌĆØ Foreign Policy, (October 7, 2020).

26. ŌĆ£Stopping the War for Tripoli: Middle East and North Africa,ŌĆØ International Crisis Group, (May 23, 2019), especially note 37; Jalel Harchaoui, ŌĆ£How France Is Making Libya Worse: Macron Is Strengthening Haftar,ŌĆØ Foreign Affairs, (September 21, 2017).

27. David D. Kirkpatrick, ŌĆ£Russian Snipers, Missiles and Warplanes Try to Tilt Libyan War,ŌĆØ The New York Times, (November 5, 2019); Michele Dunne, ŌĆ£Support for Human Rights in the Arab World: A Shifting and Inconsistent Picture,ŌĆØ Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, (December 28, 2018); Wolfram Lacher and Alaa al-Idrissi, ŌĆ£Capital of Militia: TripoliŌĆÖs Armed Groups Capture the Libyan State,ŌĆØ Small Arms Survey, (June 2018).

28. ŌĆ£Stopping the War for Tripoli.ŌĆØ

29. Keith Johnson and Robbie Gramer, ŌĆ£How the Bottom Fell Out of the U.S.-Saudi Alliance,ŌĆØ Foreign Policy, (April 23, 2020).

30. Kareem Chehayeb, ŌĆ£Saudi ArabiaŌĆÖs Biggest Obstacle to Progress Lies in Its Systematic Human Rights Violations,ŌĆØ Amnesty International, (January 30, 2018).

31. ŌĆ£Saudi Arabia: ŌĆśImage LaunderingŌĆÖ Conceals Abuses: New Human Rights Watch Campaign Against Whitewashing Rights Violations,ŌĆØ Human Rights Watch, (October 2, 2020).

32. Former Soviet Union intelligence agency, Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti, which translates to ŌĆ£Committee for State SecurityŌĆØ in English.

33. The UK Government started to look into the deal but was blocked by the courts who said that the investigation was not done soon enough. See, Jim Waterson, ŌĆ£Court Blocks Inquiry into Independent and StandardŌĆÖs Links to Saudi Arabia,ŌĆØ The Guardian, (August 16, 2019).

34. Luke Harding and Dan Sabbagh, ŌĆ£Johnson Visit to Lebedev Party after Victory Odd Move for ŌĆśPeopleŌĆÖs PM,ŌĆÖŌĆØ The Guardian, (December 22, 2019).

35. Ben Hubbard, ŌĆ£After a Year of Silence, a Jailed Saudi Princess Appeals for Help,ŌĆØ The New York Times, (April 17, 2020).

36. Adela Suliman, ŌĆ£Saudi G20 Event Slammed over KingdomŌĆÖs Treatment of Women,ŌĆØ NBC News, (October 26, 2020).

37. This is the official spelling used by the United Nations. Also spelled as ŌĆ£Al-Qaeda.ŌĆØ

38. Named after Sheikh Rabee al-Madkhali, a Saudi theologian whose followers adhere to an ultra-conservative but politically quietist ideology. See, ŌĆ£Addressing the Rise of LibyaŌĆÖs Madkhali-Salafis: Middle East and North Africa,ŌĆØ International Crisis Group, (April 25, 2019).

39. ŌĆ£Rabei al-Madkhali Calls for a Salafi Revolution against the ŌĆ£BrotherhoodŌĆØ in Libya,ŌĆØ Arabi 21, (July 9, 2016).

40. Frederic Wehrey, ŌĆ£Quiet No More? ŌĆśMadkhaliŌĆÖ Salafists in Libya are Active in the Battle against the Islamic State, and in Factional Conflicts,ŌĆØ Carnegie Middle East Center, (October 13, 2016); Lacher and al-Idrissi, ŌĆ£Capital of Militia: TripoliŌĆÖs Armed Groups Capture the Libyan State;ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Addressing the Rise of LibyaŌĆÖs Madkhali-Salafis.ŌĆØ

41. Francesca Mannocchi, ŌĆ£Saudi-Influenced Sala┬Łfis Playing Both Sides of LibyaŌĆÖs Civil War,ŌĆØ Middle East Eye, (December 11, 2018).

42. Vivian Salama, Jared Malsin, and Summer Said, ŌĆ£Trump Backed Libyan Warlord after Saudi Arabia and Egypt Lobbied Him,ŌĆØ The Wall Street Journal, (May 12, 2019).

43. ŌĆ£Stopping the War for Tripoli,ŌĆØ Paragraph 21; Jared Malsin and Summer Said, ŌĆ£Saudi Arabia Promised Support to Libyan Warlord in Push to Seize Tripoli,ŌĆØ The Wall Street Journal, (April 12, 2019); Tim Lister, ŌĆ£Battle for Tripoli Becomes a Sandbox for Outside Powers,ŌĆØ CNN, (May 7, 2019); Samuel Ramani, ŌĆ£Saudi Arabia Steps Up Role in Libya,ŌĆØ Al-Monitor, (February 24, 2020).

44. ŌĆ£Why Is Saudi Arabia Funding Russian ŌĆ£WagnerŌĆØ Mercenaries to Kill Libyans?ŌĆØ Arraed LG, (January 26, 2020); Ramani, ŌĆ£Saudi Arabia Steps up Role in Libya.ŌĆØ

45. Johnson and Gramer, ŌĆ£How the Bottom Fell Out of the U.S.-Saudi Alliance.ŌĆØ

46. ŌĆ£European Parliament Urges Arms Embargo on Saudi Arabia,ŌĆØ Amnesty International, (October 25, 2018).

47. ŌĆ£Campaign against Arms Trade vs. The Secretary of State for International Trade [CAAT -v- SSIT],ŌĆØ EWCA Civ 1020, (2019).

48. Jessica Murray, ŌĆ£UK Faces New Legal Challenge over Arms Sales to Saudi Arabia,ŌĆØ The Guardian, (October 27, 2020).

49. ŌĆ£UNHCR Operational Update for Yemen,ŌĆØ UNHCR, (September 10, 2020).

50. Katie McQue, ŌĆ£ŌĆśThey Have to Be Punished:ŌĆÖ The Mothers Trapped in the UAE by ŌĆśLove Crimes,ŌĆÖŌĆØ The Guardian, (October 12, 2020).

51. Owen Bowcott and Haroon Siddique, ŌĆ£Dubai Ruler Organised Kidnapping of His Children, UK Court Finds,ŌĆØ The Guardian, (March 5, 2020).

52. Tubiana and Gramizzi, ŌĆ£Lost in Trans-Nation.ŌĆØ

53. ŌĆ£S/2019/914 - Final report of the Panel of Experts on Libya established pursuant to Security Council Resolution 1973,ŌĆØ (2011) United Nations, Distr. General, December 9, 2019, Paragraphs 61, 62, 72-75, 96-97, 104, 108-110, Annexes 15, 32, 39, 40, 46, 47, 51, 52; ŌĆ£S/2018/812 - Final report of the Panel of Experts on Libya Established Pursuant to Resolution 1973 (2011),ŌĆØ United Nations:, Distr. General (5 September 2018), Paragraphs 75-76, 92-97 and Annexes 30 and 33; ŌĆ£S/2017/466 - Final report of the Panel of Experts on Libya established pursuant to Security Council Resolution 1973 (2011),ŌĆØ United Nations, Distr. General (June 1, 2017), Paragraphs 120-128, 132, 160-163, and Annexes 34, 35, 38, 48; ŌĆ£S/2016/209 - Final report of the Panel of Experts on Libya established pursuant to Security Council Resolution 1973 (2011),ŌĆØ United Nations, General (March 9, 2016), Paragraphs 27, 111-113, 117-119, 130-131, 140-143, 240 and Annexes 23, 26, 27, 29, 30, 35; ŌĆ£S/2015/128,ŌĆØ Paragraphs 60, 125-131, 172-174 and Annex 18; ŌĆ£Stopping the War for Tripoli;ŌĆØ Oscar Nkala, ŌĆ£UAE Donates Armored Personnel Carriers, Trucks to Libya,ŌĆØ Defense News, (April 28, 2016); Jared Malsin, ŌĆ£U.S.-Made Airplanes Deployed in LibyaŌĆÖs Civil War, in Defiance of U.N.,ŌĆØ Time Magazine, (May 9, 2017); Jared Malsin, ŌĆ£U.A.E. Boosted Arms Transfers to Libya to Salvage WarlordŌĆÖs Campaign, U.N. Panel Finds,ŌĆØ The Wall Street Journal, (September 29, 2020).

54. Rabia Golden, ŌĆ£Sudanese Mercenaries Train in the UAE Prior to Deployment in Libya,ŌĆØ Libya Observer, (May 3, 2020); ŌĆ£CAE Aviation, Joker D├®cisif de Macron et Haftar ├Ā Derna,ŌĆØ Africa Intelligence, (May 31, 2018); ŌĆ£Prince ├Ā la Rescousse des ├ēmirats en Libye,ŌĆØ Intelligence Online, (January 11, 2017); ŌĆ£Riccardo Mortara Muscle les Forces A├®riennes de Haftar,ŌĆØ Africa Intelligence, (May 17, 2018); ŌĆ£LŌĆÖaviation ├ēmiratie est l├Ā pour Rester,ŌĆØ Africa Intelligence, (January 26, 2017); Malsin and Said, ŌĆ£Saudi Arabia Promised Support to Libyan Warlord in Push to Seize Tripoli.ŌĆØ

55. David D. Kirkpatrick, ŌĆ£The Most Powerful Arab Ruler IsnŌĆÖt M.B.S. ItŌĆÖs M.B.Z.,ŌĆØ The New York Times, (June 2, 2019); ŌĆ£UAE Inciting US to Intervene in Libya,ŌĆØ Middle East Monitor, (July 1, 2020).

56. Abdelkader Assad, ŌĆ£UAE, Saudi Arabia Aiding Libya Eastern Forces, Blacklisting Qatar for Alleged Support for Other Libyans,ŌĆØ Libya Observer, (June 13, 2017).

57. ŌĆ£S/2016/209,ŌĆØ Paragraph 24 and Annex 30; David D. Kirkpatrick, ŌĆ£Leaked Emirati Emails Could Threaten Peace Talks in Libya,ŌĆØ The New York Times, (November 12, 2015); Wolfram Lacher, LibyaŌĆÖs Fragmentation: Structure and Process in Violent Conflict (London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2020), p. 45.

58. Brian Dooley, ŌĆ£How the United Arab Emirates Contributes to Mess after Mess in the Middle East,ŌĆØ The Washington Post, (July 9, 2019); Kirkpatrick, ŌĆ£The Most Powerful Arab Ruler IsnŌĆÖt M.B.S. ItŌĆÖs M.B.Z.ŌĆØ

59. According to Article 2: Islam, Principles of Islamic Sharia of the 2014 Constitution [unchanged from previous versions]: Islam is the religion of the state and Arabic is its official language. The principles of Islamic Sharia are the principle source of legislation. ŌĆ£EgyptŌĆÖs Constitution of 2014,ŌĆØ org, (August 27, 2020).

60. ŌĆ£EgyptŌĆÖs al-Azhar Poised to be stripped of its power,ŌĆØ Middle East Eye, (July 24, 2020).

61. Fran├¦ois Brousseau, ŌĆ£LŌĆÖ├ēgypte Totalitaire,ŌĆØ Le Devoir, (February 18, 2019).

62. David D. Kirkpatrick, ŌĆ£Recordings Suggest Emirates and Egyptian Military Pushed Ousting of Morsi,ŌĆØ The New York Times, (March 1, 2015).

63. Robert F. Worth, ŌĆ£Egypt is Arena for Influence of Arab Rivals,ŌĆØ The New York Times, (July 9, 2013).

64. ŌĆ£Gulf Countries Supported Egypt with $92bn since 2011,ŌĆØ Middle East Monitor, (March 19, 2019).

65. David Hearst, ŌĆ£The Emirati plan for ruling Egypt,ŌĆØ Middle East Eye, (November 23, 2015).

66. Mohamad Elmasry, ŌĆ£Egypt: Seven Years after the Coup, Repression Reigns as the Economy Tanks,ŌĆØ Middle East Eye, (July 1, 2020).

67. Olivia Alabaster, ŌĆ£Egypt Blocked UN Sanctions against Saudi Branch of Islamic State,ŌĆØ Middle East Eye, (July 6, 2017).

68. ŌĆ£S/2019/914,ŌĆØ Paragraphs 106, 72-75 and Annexes 15, 32, 44; ŌĆ£S/2018/812,ŌĆØ Paragraph 106; ŌĆ£S/2017/466,ŌĆØ Paragraphs 186-187 and Annexes 41 and 68; ŌĆ£S/2016/209,ŌĆØ Paragraphs 55, 133-137, 144-146, 179, 241, 247 and Annexes 28 and 36; ŌĆ£S/2015/128,ŌĆØ Paragraphs 167-171 and Annex 24; ŌĆ£Stopping the War for Tripoli.ŌĆØ

69. ŌĆ£Averting a Full-blown War in Libya,ŌĆØ International Crisis Group, (April 10, 2019).

70. Salama, Malsin, and Said, ŌĆ£Trump Backed Libyan Warlord after Saudi Arabia and Egypt Lobbied Him.ŌĆØ

71. Ahmed Aboulenein and Giles Elgood, ŌĆ£Is Egypt Bombing the Right Militants in Libya?ŌĆØ Reuters, (May 31, 2017)

72. Shaul Shay, ŌĆ£Egypt, France Conclude Joint Naval Exercise,ŌĆØ Israel Defense, (July 16, 2017); L├®na├»g Bredoux, ŌĆ£La France Plus Amie que Jamais avec la Dictature Militaire ├ēgyptienne,ŌĆØ M├®diapart, (June 9, 2017).

73. See for example, Jack Detsch, Robbie Gramer, and Colum Lynch, ŌĆ£After Death of U.S. Citizen, State Department Floats Slashing Egypt Aid,ŌĆØ Foreign Policy, (March 31, 2020); Brousseau, ŌĆ£LŌĆÖ├ēgypte Totalitaire.ŌĆØ

74. Phil Stewart, Idrees Ali, and Lin Noueihed, ŌĆ£Exclusive: Russia Appears to Deploy Forces in Egypt, Eyes on Libya Role -Sources,ŌĆØ Reuters, (March 13, 2017); ŌĆ£Des forces Sp├®ciales Russes en ├ēgypte, pr├©s de la Libye, R├®v├©le un Responsable Am├®ricain,ŌĆØ LŌĆÖOrient-Le Jour, (March 14, 2017).

75. ŌĆ£S/2019/914,ŌĆØ Paragraphs 92, 131-132 and Annexes 37, 38, and 51; ŌĆ£S/2018/812,ŌĆØ Paragraphs 75-76, 92-97 and Annexes 30 and 33; ŌĆ£S/2017/466,ŌĆØ Paragraphs 170, 213 and Annexes 35 and 43; ŌĆ£S/2016/209,ŌĆØ Paragraphs 164 and 167; ŌĆ£S/2015/128,ŌĆØ Paragraph 164; ŌĆ£Stopping the War for Tripoli.ŌĆØ

76. This has supposedly been confirmed by the UN Panel of Experts. The Report has not been made public yet, since Russia has blocked its publication, but several news agencies have seen copies of it and the topic has been referenced by other UN agencies such as the Working Group on the use of mercenaries. See, David Wainer, ŌĆ£Russian Mercenaries Act as ŌĆśForce MultiplierŌĆÖ in Libya, UN Says,ŌĆØ Bloomberg, (May 5, 2020); ŌĆ£UN Monitors Say Mercenaries from RussiaŌĆÖs Vagner Group Fighting in Libya,ŌĆØ Radio Free Europe, (May 7, 2020); ŌĆ£Russian GroupŌĆÖs 1,200 Mercenaries Fighting in Libya: UN report,ŌĆØ Al Jazeera, (May 7, 2020); David D. Kirkpatrick and Declan Walsh, ŌĆ£As Libya Descends into Chaos, Foreign Powers Look for a Way Out,ŌĆØ The New York Times, (January 18, 2020); Wolfram Lacher, ŌĆ£International Schemes, Libyan Realities: Attempts at Appeasing Khalifa Haftar Risk Further Escalating LibyaŌĆÖs Civil War,ŌĆØ SWP, (November 2019); ŌĆ£Why Is Saudi Arabia Funding Russian ŌĆ£WagnerŌĆØ Mercenaries to Kill Libyans?; ŌĆ£Soldiers of Misfortune - Why African Governments Still Hire Mercenaries,ŌĆØ The Economist, (May 30, 2020); For the statement by the UN Working Group on the use of mercenaries, see: ŌĆ£Libya: Violations related to mercenary activities must be investigated - UN Experts,ŌĆØ Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, (June 17, 2020); ŌĆ£S/2020/421 - Statement by the Acting Special Representative of the Secretary-General and Head of the United Nations Support Mission in Libya, Stephanie Williams,ŌĆØ United Nations, (May 21, 2020). A figure of 3,000 was mentioned by an American diplomat in an International Crisis Group Report; see, ŌĆ£Turkey Wades into LibyaŌĆÖs Troubled Waters,ŌĆØ International Crisis Group, 257 (April 30, 2020), p. 3, note 7.

77. ŌĆ£Turkey Wades into LibyaŌĆÖs Troubled Waters.ŌĆØ

78. ŌĆ£Syria War: Who Are RussiaŌĆÖs Shadowy Wagner Mercenaries?,ŌĆØ BBC, (February 23, 2018).

79. Samy Magdy, ŌĆ£US Africa Command: Russian Mercenaries Planted Land Mines in Libya,ŌĆØ The Associated Press, (July 15, 2020).

80. Andrew England, Heba Saleh, Henry Foy, and Laura Pitel, ŌĆ£UN Experts Probe Dispatch of Russian-Made Warplanes to Libya,ŌĆØ Financial Times, (May 21, 2020).

81. ŌĆ£Les Pantsir de Moscou ├Ā la Rescousse dŌĆÖHaftar,ŌĆØ Intelligence Online, (December 24, 2019).

82. Katrin Bennhold, ŌĆ£Germany Wants E.U. to Sanction Head of Russian Military Intelligence,ŌĆØ The New York Times, (May 28, 2020); ŌĆ£NSA: Russian Agents Have Been Hacking Major Email Program,ŌĆØ Security Week, (May 28, 2020).

83. Robyn Dixon, ŌĆ£Inside Room 239: How Alexei NavalnyŌĆÖs Aides Got Crucial Poisoning Evidence out of Russia,ŌĆØ The Washington Post, (October 4, 2020); David Filipov, ŌĆ£10 Critics of Vladimir Putin who Wound Up Dead,ŌĆØ Chicago Tribune, (March 25, 2017).

84. Shaun Walker, ŌĆ£The Murder That Killed Free Media in Russia,ŌĆØ The Guardian, (October 5, 2016); Lana Estemirova, ŌĆ£My Mum and Anna Politkovskaya: Women who Died for the Truth,ŌĆØ The Guardian, (October 5, 2016).

85. ŌĆ£S/2019/914,ŌĆØ Paragraphs 19, 27, 29, 31-33 and Annex 9; ŌĆ£S/2018/812,ŌĆØ Paragraph 24 and Annexes 9 and 10; ŌĆ£S/2017/466,ŌĆØ Paragraphs 83-86 and Annex 23; ŌĆ£S/2016/209,ŌĆØ Paragraphs 28, 30, 68-69; Tubiana and Gramizzi, ŌĆ£Lost in Trans-Nation;ŌĆØ Wolfram Lacher, ŌĆ£Who is Fighting Whom in Tripoli?,ŌĆØ Small Arms Survey, (August 2019); ŌĆ£Stopping the War for Tripoli;ŌĆØ Golden, ŌĆ£Sudanese Mercenaries Train in the UAE Prior to Deployment in Libya.ŌĆØ

86. S/2019/914, paragraphs 19, 28-30, 32-33; ŌĆ£S/2018/812,ŌĆØ Paragraphs 22 and 24 and Annex 9; ŌĆ£S/2017/466,ŌĆØ Paragraphs 84 and 85 and Annex 23; Tubiana and Gramizzi, ŌĆ£Lost in Trans-Nation.ŌĆØ

87. ŌĆ£S/2017/466,ŌĆØ Paragraphs 79 and 83; Tubiana and Gramizzi, ŌĆ£Lost in Trans-Nation.ŌĆØ

88. ŌĆ£S/2018/812,ŌĆØ Paragraphs 22 and 24 and Annex 9; Tubiana and Gramizzi, ŌĆ£Lost in Trans-Nation,ŌĆØ p. 14;

89. ŌĆ£S/2019/914,ŌĆØ Annex 16.

90. ŌĆ£S/2017/466,ŌĆØ Paragraph 86 and Annex 23; ŌĆ£S/2016/209,ŌĆØ Paragraphs 27, 27, 67, 177; ŌĆ£S/2015/128,ŌĆØ Paragraph 204; Tubiana and Gramizzi, ŌĆ£Lost in Trans-Nation.ŌĆØ

91. Nathalie Guibert, ŌĆ£La Guerre Secr├©te de la France en Libye,ŌĆØ Le Monde, (February 23, 2016); Taylor, ŌĆ£FranceŌĆÖs Double Game in Libya.ŌĆØ

92. See, ŌĆ£Le Mar├®chal Haftar, ├Ā la T├¬te de LŌĆÖarm├®e Libyenne: ŌĆśCŌĆÖest aux Libyens de D├®cider ce qui est Bon pour eux,ŌĆØ Le Journal du Dimanche, (February 4, 2017- updated June 21, 2017).

93. ŌĆ£S/2017/466,ŌĆØ Paragraph 133; ŌĆ£Ce nŌĆÖest plus un Secret, la France est Militairement Pr├®sente en Libye,ŌĆØ LŌĆÖObs (Avec AFP), (July 20, 2016); Inti Landauro and Hassan Morajea, ŌĆ£Three French Special Forces Soldiers Killed in Helicopter Crash in Libya,ŌĆØ Wall Street Journal, (July 20, 2016); Cyril Bensimon, Fr├®d├®ric Bobin, and Madjid Zerrouky, ŌĆ£Trois Membres de la DGSE Morts en Libye,ŌĆØ Le Monde, (July 20, 2016).

94. Direction G├®n├®rale de la S├®curit├® Ext├®rieure.

95. ŌĆ£Intelligence: Paris Deploys CAE Aviation to Keep Watch over Turkish Arms Supplies to Libya,ŌĆØ Africa Intelligence.

96. ŌĆ£CAE Aviation, Joker D├®cisif de Macron et Haftar ├Ā Derna;ŌĆØ ŌĆ£La DGSE aux Premi├©res Loges de LŌĆÖoffensive de Haftar sur Derna,ŌĆØ Africa Intelligence, (June 7, 2018).

97. ŌĆ£S/2016/209,ŌĆØ Paragraph 177.

98. France claimed that they were for the self-protection of its teams working in Libya. See, ŌĆ£S/2019/914,ŌĆØ Paragraph 93; ŌĆ£LŌĆÖembarras de Paris apr├©s la D├®couverte de Missiles sur une Base dŌĆÖHaftar en Libye,ŌĆØ Le Monde, (July 10, 2019); Lacher, ŌĆ£International Schemes, Libyan Realities.ŌĆØ

99. Jean-Yves Le Drian, ŌĆ£La France est en Libye pour Combattre le Terrorisme,ŌĆØ Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs, (May 2, 2019); Andrew England, ŌĆ£Libya: How Regional Rivalries Fuel the Civil War,ŌĆØ Financial Times, (February 25, 2020).

100. Gabriela Baczynska and Francesco Guarascio, ŌĆ£France Blocks EU Call to Stop HaftarŌĆÖs Offensive in Libya,ŌĆØ Reuters, (April 10, 2019); ŌĆ£EU, France Split on Libya as Khalifa Haftar Strikes Tripoli,ŌĆØ Deutsche Welle, (April 23, 2019).

101. ŌĆ£Stopping the War for Tripoli,ŌĆØ pp. 8-10.

102. ŌĆ£Turkey Wades into LibyaŌĆÖs Troubled Waters.ŌĆØ

103. Robin Emmott, John Irish, and Tuvan Gumrukcu, ŌĆ£NATO Keeps France-Turkey Probe under Wraps as Tempers Flare,ŌĆØ Reuters, (September 17, 2020); ŌĆ£Des Fr├®gates Turques Menacent un Navire Fran├¦ais en M├®diterran├®e,ŌĆØ Le Point, (June 17, 2020); ŌĆ£La France Suspend sa Participation ├Ā une Op├®ration de lŌĆÖOTAN en M├®diterran├®e apr├©s des Tensions avec la Turquie,ŌĆØ Le Monde (avec AFP), (July 1, 2020).

104. ŌĆ£UNHCR TurkeyŌĆöFact Sheet September 2020,ŌĆØ UNHCR, (2020). Turkey had 3,579,531 refugees and 328,257 asylum seekers, see, ŌĆ£Global Trends Forced Displacement In 2019,ŌĆØ UNHCR, (2019).

105. ŌĆ£Refugee Population by Country or Territory of Asylum,ŌĆØ The World Bank.

106. ŌĆ£UNHCR EgyptŌĆöFact Sheet July 2020,ŌĆØ UNHCR, (July 2020).

107. The ŌĆ£Global Trends Forced Displacement in 2019ŌĆØ notes another 7,270 asylum seekers (pending cases).

108. The ŌĆ£Global Trends Forced Displacement in 2019ŌĆØ notes another 2,331 asylum seekers (pending cases).

109. ŌĆ£Saudi Arabia Says Criticism of Syria Refugee Response ŌĆśFalse and Misleading,ŌĆØ The Guardian, (September 12, 2015).

110. ŌĆ£Global Trends Forced Displacement in 2019.ŌĆØ The same report lists another 102,157 asylum seekers (cases pending).

111. ŌĆ£Conventional Arms Transfers to Developing Nations, 2008-2015,ŌĆØ S. Congressional Research Service.

112. ŌĆ£Rapport au Parlement 2019 sur les exportations dŌĆÖarmement de la France,ŌĆØ French Ministry of the Armed Forces, (June 2, 2020).

113. ŌĆ£Inauguration de la base dŌĆÖAbu Dhabi,ŌĆØ French Ministry of the Armed Forces, (April 12, 2018), retrieved from https://t.ly/NVG8; Matthew Saltmarsh, ŌĆ£France Opens First Military Bases in the Gulf,ŌĆØ The New York Times, (May 26, 2009).

114. ŌĆ£Le Mar├®chal Haftar, ├Ā La T├¬te de LŌĆÖarm├®e Libyenne.ŌĆØ

115. ŌĆ£European Parliament Urges Arms Embargo on Saudi Arabia.ŌĆØ

116. ŌĆ£Egypt: How French Arms Were Used to Crush Dissent,ŌĆØ Amnesty International, (October 16, 2018).

117. Bruno Stagno Ugarte, ŌĆ£MacronŌĆÖs Selective Indignation over Libya: Void between Words and Deeds Harms French Credibility and Fight against Impunity,ŌĆØ Human Rights Watch, (July 17, 2020).