Introduction

The origins of today’s EU-Turkey partnership go back to the early years of the 1960s. An Association Agreement dated 1963 paved the way for forming a bilateral Customs Union (CU) that has been in force since 1996. Turkey earned candidacy status for EU membership in 1999, and its accession negotiations began in 2005. Nevertheless, so far Ankara has made only limited progress toward membership owing to mounting political hurdles on both sides. The negotiations have been effectively stalled in recent years amid the biggest political crisis in bilateral relations. Rising populist nationalism in Western Europe, the Brexit decision, and increasingly unified resistance to Turkey’s accession within the EU have made Turkey’s full membership an impossible scenario.

Although proponents of Turkey’s EU membership both in Europe and Turkey have long lost faith in a happy ending, neither Ankara nor Brussels is ready to terminate the accession process and work out a mutually non-destructive Plan B. In their October 2017 summit in Brussels, the EU leaders produced a decision, at the end of hours of heated debate, that limits structural aid for Turkey’s accession owing to persisting concerns about the conditions of democracy and human rights in the country.1 The European Commission’s latest progress report on Turkey’s accession contends that Ankara fails to meet not only political criteria for being in the EU but also increasingly falls short of maintaining its market economy. Even though a decision that would officially cut off the accession talks has so far been evaded, the policy debate will certainly intensify in European capitals toward constructing a viable exit strategy that would officially terminate the membership process but keep Turkey anchored to Europe. This time the proponents of the idea of a “Privileged Partnership” with Turkey will shape the policy debates in Europe, rather than those who back Turkey’s membership bid. Upgrading the CU is central to the Privileged Partnership proposals.

Aside from the joint security architecture, it is clear that CU 2.0 will become the sole institutional framework to engage Ankara with Europe and carry the partnership into the future

The European Commission (EC) and the Turkish government have already launched a process that would expand and upgrade the two-decades-old CU. In May 2015, Turkish Economy Minister, Nihat Zeybekçi, and European Commissioner for Trade, Anna Cecilia Malmström, reached a mutual understanding to modernize the trade pact and extend it to new domains. Originally, the plan was to address the imminent institutional defects of the current CU and to broaden its market access scope to farming, services, and public procurement. In December 2016, the EC announced its objectives and scenarios for the forthcoming talks, and called for a negotiation mandate from the member states.2 The Commission proposed a broader package for CU 2.0 than the mutually agreed framework adopted in May 2015. Going beyond conventional trade pacts, the EC proposed delineating a “mega-regional” between Turkey and the EU with deep market access commitments, and a comprehensive rules and enforcement agenda. This development must please the advocates of Privileged Partnership in Europe; because the proposed pact would further open Turkish markets, it would not only strongly anchor Turkey with Europe, but also eradicate the EU’s motives to accept Turkey as a full member.

Although the two parties are anticipated to start the update negotiations in 2018, there has been almost no debate in Turkey on how to repair ties and move forward with the nation’s biggest economic partner and political ally. As a matter of fact, neither the idea of a Privileged Partnership nor a modernization of the CU have been a subject of debate for policymakers, economists, or international relations experts. This paper is a modest contribution to kick off the policy debate about alternatives to Turkey’s EU membership by focusing on the upgrade of the CU. Specifically, the paper will assess the EC’s CU upgrade scenarios in light of the Privileged Partnership ideas raised in Europe. As a Turkish advocate of the idea of Privileged Partnership, I argue that the CU 2.0 project will indeed be a grandiose step toward such a partnership between the two parties. Aside from the joint security architecture, it is clear that CU 2.0 will become the sole institutional framework to engage Ankara with Europe and carry the partnership into the future. Nevertheless, this may not necessarily be a bright future for Turkey since the scenarios proposed by the Commission are likely to lead to a more imbalanced outcome in terms of costs and benefits than that of CU 1.0.

This paper will first outline the current state of Turkey’s EU accession process and elaborate upon the Privileged Partnership alternative. It will then focus on CU 1.0, study its defects, and shed light on the process to upgrade its structure and scope. Before concluding, the paper will analyze the Commission’s CU update scenarios against the idea of a Privileged Partnership elaborated in European policy circles.

Turkey’s EU Membership: A Failed Project

The historic decision in the EU’s 2004 Copenhagen summit which inaugurated the accession talks with Turkey was an outcome of the determination of Turkey’s then Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the entrenched support and visionary leadership of Jacques Chirac, Tony Blair, and Gerhard Schröder.3 Nevertheless, this decision did not mean an unconditional ‘yes’ to Turkey’s EU membership. It rested on a conditional compromise built between pro-Turkey and anti-Turkey forces in Europe. The accession negotiations were set to become “open-ended,” with no guarantee that they would result in full membership.4 Such an awkward start reflected the strong resistance of some European leaders who admitted Turkey’s strategic significance for Europe yet opposed it becoming a member of the Union. Instead of membership, the opponents suggested constructing a Privileged Partnership with Turkey. The leader of Germany’s Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU), Angela Merkel, was an outspoken opponent of Turkey’s accession before and after she was elected chancellor in 2005, in company with other high-profile European leaders such as Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, former French President and President of the European Convention that produced the draft Constitutional Treaty, and Nicolas Sarkozy who led the Union for a Popular Movement and succeeded Jacques Chirac in the French presidency in 2007.5 In contrast to the large backing for the idea in Europe, Privileged Partnership has never garnered support in Turkey. The Turkish government has not officially come to terms with any alternatives to full membership.

French resistance after Sarkozy came to office, German indifference under the leadership of Merkel, and the Cypriot veto stymied any swift progress in Turkey’s membership talks. The accession process typically takes place over 33 of 35 chapters of the EU acquis and requires candidate countries to harmonize their domestic laws with European standards and policies. Especially in the early phases of the talks, Turkey undertook significant reforms in order to align its domestic laws with the EU acquis in several chapters. Yet Turkey’s accession negotiations, which formally began in October 2005, have been filled with landmines. In 2006, the EU suspended the negotiations in eight chapters pertinent to the functioning of the CU. This was because of Turkey’s resistance to implementing an additional protocol to the Copenhagen Council decision, which would expand the CU to new members including Cyprus. The following year, France under Sarkozy’s leadership blocked four chapters, which arguably belonged in the final phase of negotiations.6 In the face of the changing balance of power in Europe that strengthened the anti-Turkey camp, Ankara lost its appetite for new reforms to align its domestic legislation with the EU.

Turkey’s EU membership is a failed project with no chance of revitalization in the foreseeable future, and a Privileged Partnership remains the only mutually non-harming way forward

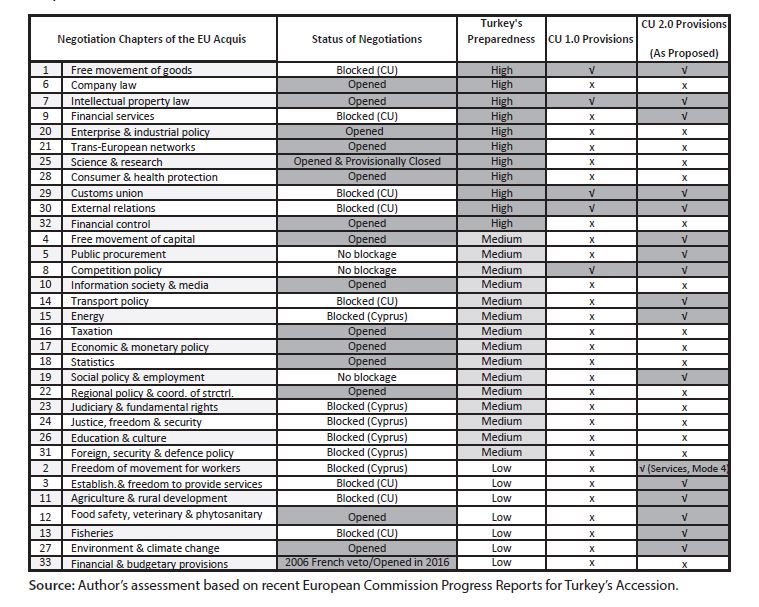

As seen in Table 1, less than half of the acquis chapters (16 chapters) have so far been opened to negotiation, whereas only one chapter, Science and Research, has come to temporary closure. In 11 chapters, Turkey has highly aligned its domestic regulations with the acquis. These include areas regulated by the CU rules, such as competition policy and intellectual property rights (IPRs), which had to be harmonized earlier because of the CU rather than the accession process per se. On the other hand, Turkey is still in the early stages of harmonization in domains such as agriculture and rural development, food safety, fisheries, and the environment. This group of policy domains is marked by wide gaps between Turkish and EU standards, and Ankara needs to undertake costly reforms to catch up with Europe.

Table 1: Turkey’s Level of Harmonization to EU Standards in Individual Chapters of the Acquis

Although Turkey and the European Union pushed for reinvigorating the accession talks after Sarkozy lost the French presidency in 2017, these endeavors have not been utterly productive. Especially since 2013, the EU-Turkish partnership has seen the deepest political crisis in recent history together with a complete erosion of confidence in relations. European leaders and institutions have been critical of Turkey for breaching its obligations in human rights and for the rising authoritarianism in the country. The leaders of the ruling Justice and Development Party, including President Erdoğan have responded with harsh statements, accusing the EU of double standards against Turkey and suggesting that European criticisms are merely interference in Turkish domestic affairs.7 The crisis has deepened since the failed coup attempt in July 2016, the ensuing state of emergency, which remains in effect at the time of writing, and the political campaign of the Turkish government to build up a presidential system that would grant sweeping new powers to the Turkish president. Nonetheless, Turkish and European leaders alike have avoided throwing the first stone that would officially break down the accession process. Clearly, Turkey’s EU membership is a failed project with no chance of revitalization in the foreseeable future, and a Privileged Partnership remains the only mutually non-harming way forward.

“Privileged Partnership” as an Exit Plan?

The proponents of a Privileged Partnership raised the option in the early 2000s as an alternative to what they saw as an undesired EU decision to embark upon membership talks with Turkey. They suggested that Turkey did not belong in Europe because of a number of geographical, cultural and/or identity reasons. Highlighting the costs of Turkey’s membership to Europe, the Privileged Partnership advocates continued to argue against a potential Turkish accession even after the initiation of accession talks with Ankara in October 2005.8 In fact, their concerns were taken into account in the framework of the negotiations which turned the talks, in view of the EU’s “absorption capacity” to an “open-ended” process with no guarantee of membership.9 In a sense, the Privileged Partnership alternative has remained on the table as a “Plan B” in Angela Merkel’s words, ‘to prevent failure or catastrophe’ at the end of the talks.10 Now that the negotiations have reached an impasse, it is high time to examine the Privileged Partnership idea as a plausible exit scenario from the current stalemate.

Depending on the depth of integration desired, proponents have suggested that Turkey align its policies on a wide set of policy issues

While earlier proposals did not elaborate upon the idea, statements and publications following the initiation of the talks in 2005 emerged to offer a clearer picture of what a Privileged Partnership could actually look like. Overall, European advocates of the idea concur on three overlapping objectives to be pursued through special institutional mechanisms between the EU and Turkey: (i) The partnership should ensure Ankara’s contribution to European security and political stability by closely anchoring Turkey to Europe; (ii) In conjunction with the first objective, the partnership should also maximize the benefits from Turkey’s stronger association with Europe by enabling mutually beneficial cooperation in multiple realms such as trade, investment, energy, and security; (iii) Finally and most importantly, the partnership should minimize the costs of associating Turkey with the EU, which would become overwhelming in case of a full membership.11

The proponents of a Privileged Partnership almost univocally agree on the need to avoid the insurmountable budgetary burden on the EU’s agricultural and cohesion funds, and the direct or indirect burdens that would stem from the mobility of labor between Europe and Turkey. In fact, these concerns were partly reflected in the negotiation framework, which allows for long transitory periods and exemptions in areas such as freedom of movement of persons, structural policies, and agriculture.12

In this context, Privileged Partnership would mean strengthening ties in security and foreign policy as well as in justice and home affairs, ensuring continued reforms in Turkey toward uninterrupted democratization, and enhancing minority and human rights.13A proponent of this position, Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg, a former German minister for defense and economic affairs on Merkel cabinets, suggested the two sides deepen ties with the “prospect of [Turkey’s] membership in European foreign, security and defense policy structures on an equal basis,” for security, geostrategic and other reasons.14 On the economic front, Privileged Partnership proposals usually revolve around reforming and expanding the CU starting with an enlargement of its scope to services and farming. An earlier report, dated 2004 presented to the French Senate by Robert Del Picchia and Hubert Haenel, argued for a Euro-Turkish economic integration which would enable three out of four freedoms of the Union (i.e., freedom of movement of goods, services, capital and labor).15 The report excluded the possibility of the forth freedom, i.e., free movement of persons/labor. A comprehensive pamphlet, “Brochure no: 38” by the Robert Schumann Foundation on ‘The Privileged Partnership, an Alternative to Membership,’ asserted that Turkey must not be excluded from the Common Agriculture Policy (CAP) of the EU, and that Ankara should decide whether it will be part of the Eurozone or not.16 Depending on the depth of integration desired, proponents have suggested that Turkey align its policies on a wide set of policy issues. For instance, Chancellor Merkel stated she was “confident that 27-28 [out of 35 chapters of the EU acquis could] be taken up [during negotiations]” and this would “really mean a privileged partnership.” As part of this statement, made to a group of Turkish reporters ahead of a visit to Turkey in 2010, she revealed that issues like “institutional integration” would be left out.17

In alignment with those objectives, proponents of a Privileged Partnership have favored alternative institutional models. While some opinion-makers argued for a ‘Ukraine model,’ others have contemplated a structure similar to the legal framework between Norway and the EU. To exemplify, Guttenberg proposed replicating the structures and institutions of the European Economic Area (EEA). In addition to expanding cooperation in the Association Council, he suggested the formation of an EU-Turkey Committee that would monitor Turkey’s alignment with the EU’s acquis to be covered by the Privileged Partnership.18 By the same token, Brochure no: 38 of the Robert Schumann Foundation argued for setting up dedicated commissions between Turkey and the EU for representatives from both sides to work on various issues of common concern. Brochure 38 also speculated on forming a special general fund mechanism, which would provide fiscal support to privileged partners including Ukraine and Turkey.19

CU 1.0 is actually an “incomplete” customs union which does not allow Turkey to be part of the EU’s internal CU and Single Market

In a recent article dated June 12, 2017, Pierre Mirel, a former Director at the European Commission’s DG Enlargement between 2001-2013, presented a more detailed proposal for a four-pillar Privileged Partnership framework.20 At the center of the framework sits an expanded and modernized CU. In other pillars, he advocates updating the Association Agreement in line with the recent EU-Ukraine Agreement, which envisages closer cooperation in areas of justice and fundamental rights, security, energy, transport, and the environment. Further, he backs Turkey’s association in the Foreign Affairs Council regarding regional issues and Ankara’s adoption of the EU’s acquis in vital domains such as energy and the environment. For the time being, however, he rightly notes that the modernization of the CU is the “only realistic path” that would work for both parties. In fact, the EC’s proposition for a comprehensive CU 2.0 goes well beyond the first pillar Mirel refers to. It sets a larger agenda that would take the contractual partnership beyond conventional trade issues by setting enforceable standards for, among others, energy and raw materials, capital movements, the environment, labor conditions, transparency in domestic legislation, and human rights.

Customs Union 2.0: Revising a Badly Negotiated Trade Deal for a Trade-Plus Mega-Regional Agreement

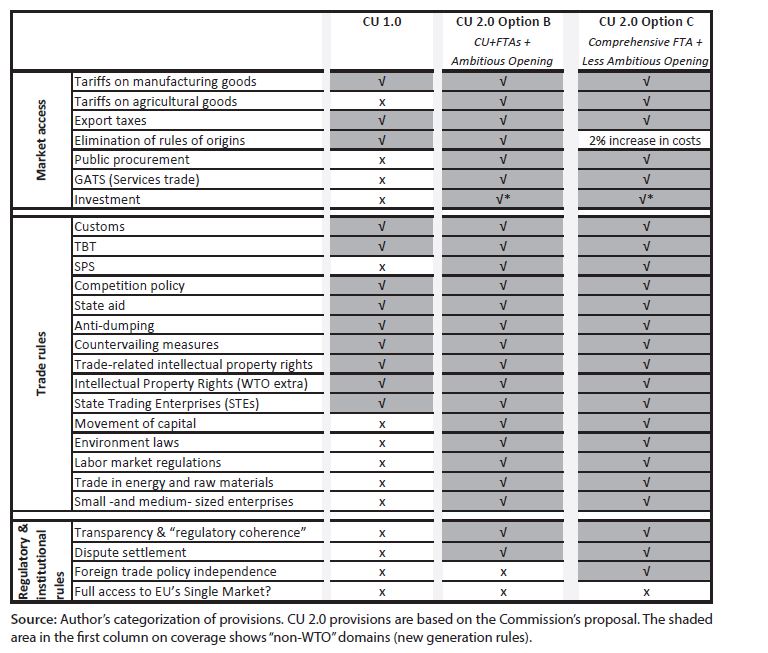

In a press conference held in January 2011, former Turkish Minister of Economy, Zafer Cağlayan, publicly blamed the Tansu Çiller government that inked the CU in 1995 for the ‘mistake’ of signing on the EU proposed text with no proper negotiation of the terms of the commercial deal.21 Indeed, for Turkish stakeholders, the CU has had several defects because it was not negotiated properly. CU 1.0 is actually an “incomplete” customs union which does not allow Turkey to be part of the EU’s internal CU and Single Market. The deal eliminated tariffs on industrial products and processed farming goods, while excluding primary agricultural goods and trade in services from its scope. In terms of trade rules, the scope of the CU contained only rules about trade remedies, customs legislation and technical standards in industrial products in addition to new generation rules on intellectual property rights (IPRs) and competition policies22 (See Table 1 and 2).

Table 2: A Comparison of Provisions of CU 1.0 and Proposed CU 2.0 (Option B and C)

In contrast to free trade agreements (FTAs), which do not interfere with the independence of the parties’ conduct of trade policies with the third parties, CUs require common external tariffs and policies. In other words, the CU has obliged Turkey to assume the EU’s Common Commercial Policy (CCP), which includes the EU’s unilateral and preferential trade regimes as well as its Common External Tariff (CET). This has not only resulted in Ankara’s loss of trade policy independence but also diminished Turkey’s bargaining power vis-à-vis third parties. In order to avoid being harmed by a trade deflection from third parties, Turkey has been required to conclude flanking FTAs with the EU’s FTA partners without questioning Brussels’ decisions or taking part in the European policymaking processes. In practice, however, the third parties, which de facto gain the right to “free ride” the Turkish market via the CU have usually been hesitant to engage in a quick flanking FTA with Turkey.23 This has led to the infamous “FTAs asymmetry” problem at the center of the complaints of Minister Çağlayan and other Turkish stakeholders. The asymmetry problem became a source of frustration for Turkey from the mid-2000s, when the EU adopted a new trade strategy and started negotiating comprehensive FTAs with sizable economies such as South Korea and Canada. The commencement of the talks for a transatlantic mega-regional agreement known as the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) in 2013 was unacceptable for Turkey. Ankara desperately called for joining the TTIP talks in order not to get hurt from a trade deflection from the U.S. It eventually came to terms with the Europeans’ demand to upgrade the CU as a precondition for joining the TTIP following the completion of the transatlantic talks.24

The primary objective of the EC is to further open up the Turkish market to realize its “unfulfilled economic potential,” especially in agriculture, services, and public procurement

Taking into account Turkey’s growing frustration with the FTA asymmetry problem and Ankara’s willingness to engage in a mega-regional pact with transatlantic partners, the EC commissioned a comprehensive assessment report on the CU from the World Bank. Following the publication of the Bank’s study, Turkey and the EC established a Senior Officials Working Group (SOWG) to assess its findings and recommendations.25 The SOWG, which operated between February 2014 and April 2015, produced a set of joint recommendations that set the stage for the start of CU upgrade negotiations.26 Senior officials have agreed on a general framework to upgrade the CU toward addressing its institutional deficiencies and expanding its coverage to services, agriculture, and public procurement. Nevertheless, the EU had a longer list of issues that could be handled through a comprehensive mega-regional pact with Turkey. This fact was revealed by an EC communication in December 2016 that asked for a negotiation authority from the Council of the EU in order to kick off negotiations with Turkey.27

The EC’s Negotiation Objectives and Scenarios

Bursa Industrial Zone (OSB), opened to service the track parking, a requirement for the candidate countries to the EU member states under the regulation “Intelligent Transport Services for Road Transportation”. ALİ ATMACA / AA Photo

Bursa Industrial Zone (OSB), opened to service the track parking, a requirement for the candidate countries to the EU member states under the regulation “Intelligent Transport Services for Road Transportation”. ALİ ATMACA / AA Photo

The EC proposal outlines the European objectives for the upgrade process and offers three scenarios together with a detailed impact study. The primary objective of the EC is to further open up the Turkish market to realize its “unfulfilled economic potential,” especially in agriculture, services, and public procurement. Secondly and more importantly, the EC proposes to address Turkey’s “non-compliance” problem by building a mega-regional pact which would include an effective Dispute Settlement Mechanism (DSM).28 The EC contends that Turkey has failed to honor its existing CU obligations regarding the use of tariffs, trade remedies (anti-dumping and safeguard measures) and other non-tariff barriers (NTBs). Allegedly, the Turkish market increasingly lacks predictability and certainty for European businesses owing to governmental policies that are in contradiction with the CU rules and the EU’s acquis in areas such as IPRs and competition policy (e.g. state aid measures including steel subsidies and localization incentives). To this end, the EC has laid out three scenarios for the future:

Option A: The Baseline Scenario

This first scenario maintains the status quo. The European Commission portrays this option as a “nightmare scenario,” because doing nothing will potentially open the door to bigger issues regarding Turkey’s non-compliance in the absence of a working enforcement tool. A major concern is that Turkey may act independently from Brussels by concluding FTAs with third parties of its own choice (for example with Russia, Iran, and Central Asian Turkic Republics or the United States) while extending certain privileges (i.e., preferences) to those parties rather than to the EU.29

Option: B: An Upgraded CU + Sectoral FTAs

The second option extends CU 1.0 by negotiating additional FTAs on services, agriculture, and public procurement, and by carving out additional chapters on trade and new generation rules (Table 1). One might deem this option the “ideal scenario” in terms of its fulfillment of European interests and the aspirations of the supporters of Privileged Partnership. This scenario envisages modernizing the CU by addressing Turkey’s non-compliance problem, and granting new market access privileges to European exporters and investors in Turkish services, agriculture, and public procurement markets via individual FTAs between the two signatories.30 To ensure a predictable business and political environment in Turkey, this scenario proposes an extensive trade and non-trade rules agenda that would align Turkey with the EU’s acquis in numerous areas, if not all 25-27 chapters as contemplated by Chancellor Merkel. The last but not least important element, of course, is negotiating a legally binding Dispute Settlement Mechanism (DSM) to ensure enforcement of the rules of the new mega-regional agreement.

Option C: Replacing the CU with a Comprehensive FTA

The final scenario envisions the replacement of the existing CU with a comprehensive FTA along the lines of the EU’s recent mega-regional initiatives with developed economies, such as the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA).31 Like Option B, Option C seeks to ensure the same market access gains in extended domains as well asthe same rule coverage and DSM. Yet the Commission proposes Option C as a backup plan for Option B, “in case the two sides do not manage to agree on solutions to address the deficiencies of the functioning of the CU.”32 Indeed, as discussed below, Option B is already doomed to fail to address Turkey’s FTA asymmetry problem, which is at the very center of Turkey’s complaints about CU 1.0.

The final scenario envisions the replacement of the existing CU with a comprehensive FTA along the lines of the EU’s recent mega-regional initiatives with developed economies, such as the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement

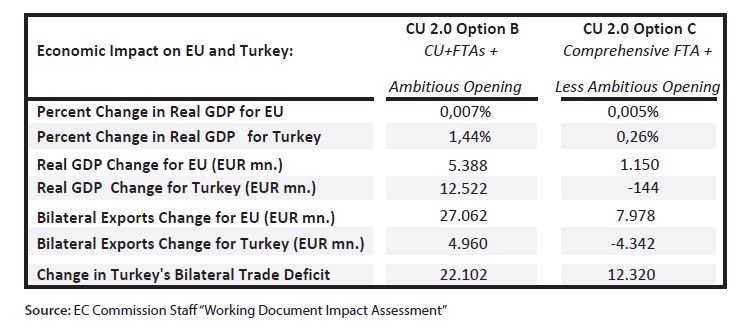

The two options proposed by the Commission will turn the CU into a mega “trade-plus” agreement that has both commercial and non-commercial implications. Commercially, the EC expects CU 2.0 to produce notable welfare gains for both parties. This is not surprising, considering the strength of economic ties between Turkey and the EU. The EU is Turkey’s top trade and investment partner, and Turkey is the EU’s 4th biggest export market, and the 5th largest supplier of good imports to Europe. Bilateral trade volume amounted to $159 billion in 2017, making 41 percent of Turkey’s total trade volume ($391 billion). The EC data indicates that Turkey also exported €16.4 billion value of services to the EU in return for a €12.2 billion value of imports in the same year.33 According to the Turkish Central Bank, between 2002 and 2016, 68 percent of FDI inflows to Turkey originated from EU countries. As detailed in Table 3 below, CU 2.0 is anticipated to create a positive, real GDP for the two sides, thanks to an increase of trade and investments, especially in services and farming, as a result of the elimination of outstanding trade barriers. The EC estimates the magnitude of the bilateral trade gains of the EU to be between 12 and 22 billion EUR,depending on the extent of trade opening. However, as seen in the table CU 2.0 would yield an asymmetric increase in EU exports to Turkey, and a growth of Turkey’s bilateral trade deficit because of a surge in imports from Europe.

Table 3: Anticipated Economic Impact of CU 2.0 on the EU and Turkey

On the non-commercial front, the proposed mega-regional agreement (both Option B and Option C) would require Ankara’s compliance with an expansive range of rules set by at least 20 chapters of the EU’s acquis (compare Table 1 and 2). As given in Table 1, CU 2.0 will contain provisions regarding several new generation rules that are not covered in conventional trade agreements (new generation areas are shown in gray on the first column of the table). While the new package will potentially include additional obligations on competition and intellectual property rights, it would also have binding provisions on the following issues: (i) Sanitary and Phytosanitary Standards (SPS rules) concerning the farming and food industries); (ii) Trade and sustainable development (i.e., environment and labor standards); (iii) Energy and raw materials; (iv) Capital movements; (v) Geographical indicators; (vi) Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs); (vii) Transparency.34

Through such a grandiose package the EC aims to enable “a more stable and predictable legal and economic environment,” but also to “consolidate and support human rights” in Turkey thanks especially to the proposed rules on transparency and the chapter on sustainable development. CU 2.0 also proposes to help “preserve and improve the quality of the environment and the sustainable management of global natural resources,” in accordance with the principles of the treaties of the EU.35

From CU 1.0 toward a Privileged Partnership?

A more detailed cost-benefit analysis of the new contractual framework for both parties supports the underlying thesis of this paper that CU 2.0 would be a gigantic step toward the idea of a Privileged Partnership. In fact, CU 2.0 would attain all three objectives set by the European advocates of the idea as outlined above. CU 2.0 would anchor Turkey to the EU in a stronger and multifaceted manner, and maximize the Turkish contribution to European economic and political stability. It would also minimize the probable economic and political costs of partnership to Europe.

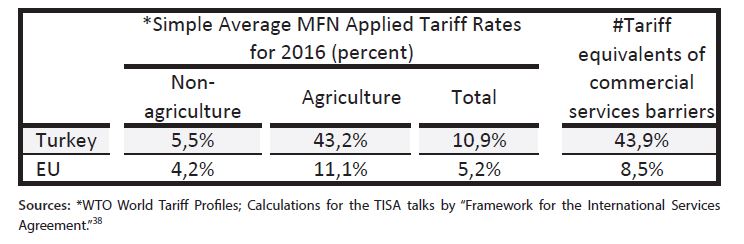

In fact, the proposed CU 2.0 scenarios are highly cost-effective for Europe, if not for Turkey. For the EU, CU 2.0 would maximize the potential economic benefits from Turkey by fulfilling European offensive interests both in trade and investment, without offering full membership to Ankara. The economic benefits of CU 2.0 for the EU derive from additional and privileged European access to Turkey’s lucrative service, farm,and public procurement markets. CU 2.0 would provide more privileges to the EU than it offers to Turkey because the new agreement would eradicate more tariff and non-tariff barriers (NTBs) in the Turkish market than in the EU market (See Table 4). Turkey has a less open market and will have to eliminate its relatively much higher tariffs and NTBs in all sectors in an asymmetric fashion vis-à-vis the EU.36 In turn for those economic and political benefits, the EC promises neither to transfer structural funds to Ankara nor to offer full Turkish access to the EU Single Market. The political costs of the free movement of Turkish labor, which would be required in the case of full membership, are carefully avoided in CU 2.0. Moreover, Turkey’s compliance with the EU rules, Ankara’s implementation of its CU 2.0 obligations, and its domestic law-making processes would be closely monitored by the EU through new binding and non-binding enforcement mechanisms.37 Put bluntly, CU 2.0 would replace the EU membership carrot with legal enforcement sticks and institutional mechanisms to ensure Turkey’s compliance with a large number of European trade and non-trade regulations on a dynamic basis.

Table 4: EU and Turkish Barriers to Trade in Goods and Services Compared

CU 2.0 Costs and Benefits for Turkey

Obviously, Turkey is entirely unprepared for negotiating the most comprehensive trade pact of its modern history. We have not been informed about Turkey’s negotiation objectives, expected negotiation scenarios, or the economic and policy impacts of those scenarios.39 Turkey’s offensive, defensive, and strategic interests have been subject to neither a thorough academic analysis nor a policy debate.40 Yet a preliminary assessment indicates that the Commission’s proposed policy options for upgrade are likely to provide more privileges and benefits for the EU than for Turkey. At the top of the benefits rows for Turkey comes enhanced consumer welfare because of the influx of cheaper imported European products into the Turkish market. Even if the proposed scenarios will not augment Turkish exports to the EU as much as the growth of imports from Europe (see Table 3), the volume of bilateral trade and investment would grow. Enhanced transparency in economic transactions and more competition in domestic markets would also benefit the Turkish economy. Higher competition in the domestic market would increase production efficiency in addition to consumer welfare. Finally, Ankara’s adoption of a larger and higher set of standards, and better participation in EU policymaking mechanisms would certainly contribute to the rule of law and good governance in Turkey.

Turkey’s cost list far exceeds those benefits. The top challenges Turkey would face are larger trade and current account deficits, significant adjustment and implementation burdens, and the (unforeseen) policy costs of an ambitious regulatory agenda

However, Turkey’s cost list far exceeds those benefits. The top challenges Turkey would face are larger trade and current account deficits, significant adjustment and implementation burdens, and the (unforeseen) policy costs of an ambitious regulatory agenda. The gains for Turkey summarized in Table 3 would originate from enhanced consumer welfare (more than producer/exporters’ welfare) because of a dramatic rise in imports from Europe. It is evident that Turkey would see an imports influx in several farm products (cereals, oil seeds, dairy and meat products), energy, coal, and steel products as well as several industrial goods including second-hand cars and machinery (currently restricted by Turkey).41

In turn for a sharp rise in imports, Turkey is unlikely to secure the expected exports expansion on an equal footing. Even though Turkey has a comparative advantage in some farm products such as fruits and vegetables, CU 2.0 is unlikely to provide privileged access for Turkey in EU markets. This is simply because CU 2.0 (in its current form) is unlikely to lift the most notable non-tariff barriers to Turkish exporters to EU markets, such as those derived from the higher European SPS standards. In order for Turkey to catch up with the EU standards, the Turkish government would have to allocate several billion Euros to upgrade Turkish farms and production facilities, especially for dairy, fruits, and vegetables.42

Since membership is no longer an option, the sole contractual framework that will bind Turkey and the EU for the foreseeable future will be an upgraded Customs Union

A fast and ambitious market-opening and agreement to these comprehensive rules would result in dramatic adjustments and high implementation costs for Turkey. The EC is proposing to Turkey almost the same package of rules it offers to high-income economies such as Canada (through the latter did recently sign CETA).43 As seen in Table 1, some of the rules envisioned in CU 2.0 will be in costly areas for a developing country like Turkey. Exits of firms from the market are likely in industries that are presently protected by high tariffs, trade remedies, subsidies and lower or deliberately unenforced standards. An ambitious liberalization in agriculture would inevitably cause rural unemployment.44 In order to abide by its ambitious commitments to CU 2.0, Turkey would need to undertake high-budget investments and regulatory reforms.45 Since the CU would impose its rules with a binding DSM, non-compliance would also cost Turkey potential trade sanctions.

With regard to CU 2.0’s (unforeseen) policy costs, Turkey’s greatest challenge would be the loss of its industrial policy space/autonomy because of an ambitious regulatory agenda. CU 2.0 clearly requires a radical development policy revision because of new disciplines on public procurement and localization that would restrict the Turkish government’s instruments for the purposes of enhancing industrial competitiveness, diminishing current account deficits, attracting investment and technology, and securing a sustainable supply of critical inputs.46 CU 2.0’s rules on energy and raw materials, along with its export restrictions, would place limitations on Turkey’s input supply policies. On the foreign policy front, Ankara is likely to encounter a challenge from Cyprus. After negotiating CU 2.0, Turkey will have to extend it to Cyprus in order to put it into force, a move which could have political implications for Turkey’s policies toward Cyprus.

In addition to limited benefits and serious costs, the Commission’s CU 2.0 seems unable to provide a cure to Turkey’s FTA asymmetries conundrum. In Option B, the EC astutely commits itself only to “explore” potential procedural options towards enabling Turkey’s participation in EU bodies and processes of policymaking so that Turkey has a say on the EU’s FTA policies and negotiation processes. Ankara does not get a clear promise for being able to engage in actual “decision making” in CCP and CU-related matters. In fact, such an engagement is a technical impossibility since Turkey is not an EU member.47 What is left to Ankara is to take part in “decision-shaping.” Put differently, what Ankara can get from the Option B is a platform to express its opinions on CU-related policies and rule-making with no veto power. Alternatively, Option C may benefit Turkey on the FTA asymmetries issue, yet with some costs that might be created by the replacement of the CU with an FTA model owing to a re-installment of the rules of origin. As it would remove Turkey’s obligation to adopt the EU’s CCP and external tariffs, a super FTA between Turkey and the EU would allow Ankara to carry out its external trade policy independently from Brussels. With an FTA-based alternative to a CU-based model, Turkey may regain its sovereignty on trade policies and start using preferential trade instruments to pursue regional leadership and other strategic goals. Nevertheless, with a content and ambition as proposed by Option C of the Commission, a Turkey-EU FTA would still result in the costs and benefits analyzed above.

Conclusion

In a recent public briefing, the President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker noted, “I believe that Turkey –as matters stand– is not in a situation to be able to join soon, nor even over a longer term.”48 In a Welt interview, EU Enlargement Commissioner Johannes Hahn explicitly stated that “The EU and Turkey should focus on the development of a strategic partnership and not on accession negotiations in the coming years.”49 Turkish President Erdoğan also maintains the view that Ankara will not be requesting to join the Union indefinitely, because it no longer needs full membership.50 The European Commission is seeking a green light from the member states to begin negotiating CU 2.0. Yet negotiations will have to wait for a formal ‘yes’ from the forthcoming government in Germany, since Berlin hesitates to start the upgrade talks. Affirming my point that “membership is no longer on the table,” Nathalie Tocci, Special Adviser to EU High Representative/Vice-President Federica Mogherini, implies that Berlin will eventually come to terms because CU 2.0 is “mostly to the interest of Germany among 28 member nations.”51

Since membership is no longer an option, the sole contractual framework that will bind Turkey and the EU for the foreseeable future will be an upgraded Customs Union. The options proposed by the EC for CU 2.0 will be a major stepping-stone toward fulfilling the goal of a Privileged Partnership, yet with asymmetric outcomes for Turkey in terms of costs and benefits. Yet the Commission’s scenarios will neither provide maximum benefits to Turkey from a partnership with Europe nor resolve Turkey’s FTA asymmetries problem. Since TTIP is no longer on the agenda, there is no need for Ankara to rush to launch upgrade negotiations that could pave the way for another bad deal for Turkey. It is high time for Ankara to produce its own cost-effective scenarios for the forthcoming CU 2.0 pact by taking account of the fact that this deal will not be a step toward full membership, but rather a building block for a Privileged Partnership.

Turkish policymakers and experts in economics and international relations should contribute to the policy debate with substantive ideas that would help assess these and other options for potential costs and benefits for Turkey and Europe. The most urgent research questions to explore include: What is the best outcome for the CU 2.0 process for both parties? What are Turkey’s policy options including and beyond a CU-model? Would a “Ukraine model” work for Turkey? Or would a “Norwegian-style” EEA-inspired partnership better benefit both parties? I would preliminarily suggest that a Norway model might incur costs similar to the EC’s two options, but would at least enable trade policy independence for Turkey and allow Turkish citizens to move and work freely in the EU market. Turkey could also exempt some sensitive farm products from liberalization in such a model. On the other hand, a Ukraine model might be more feasible, considering potential resistance from the EU to the free movement of Turkish labour in Europe. Such a model would establish an FTA-based relationship but with a lighter content, incurring fewer costs and enabling trade policy independence if not labor mobility.

Endnotes

- Accession aid earmarked for Turkey by 2020 amounts to €4.5 billion. Nikolaj Nielsen, “EU Summit Shifts Mood on Turkey Amid Aid Cuts,” EU Observer, (October 20, 2017), retrieved January 15, 2018, from https://euobserver.com/enlargement/139571.

- “Commission Staff Working Document Impact Assessment,” European Commission, (December 21, 2016), retrieved January 5, 2018, from http://ec.europa.eu/smart-regulation/impact/ia_carried_out/docs/ia_2016/swd_2016_0475_en.pdf.

- Pierre Mirel, “European Union-Turkey: From an Illusory Membership to a ‘Privileged Partnership,’” Robert Schuman Foundation, No. 437, (June 12, 2017), retrieved January 5, 2018, from https://www.robert-schuman.eu/en/european-issues/0437-european-union-turkey-from-an-illusory-membership-to-a-privileged-partnership#ancre_18.

- “Negotiation Framework: Principles Governing the Negotiations,” European Commission, (October 3, 2005), retrieved January 15, 2018, from http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2007/september/tradoc_135916.pdf.

- For a summary of their views see, Özgür Beyazıt, “Privileged Partnership: As an Alternative Way to Turkey’s European Union Membership Bid,” Law & Justice Review, Vol. 5, No. 9 (December, 2014), pp. 277-339.

- The French government stopped blocking negotiation chapters after François Hollande came to power in 2012. For the state of EU-Turkey relations and negotiations in chronological order, see pages of the Turkish Ministry of EU Affairs, retrieved January 15, 2018, from https://www.ab.gov.tr/siteimages/2017_08/kronoloji.pdf.

- For example, “Erdoğan’dan AB’ye Tepki: Haçlı Ittifakı Kendini Gösterdi,” Yeni Akit, (March 27, 2017),

retrieved January 15, 2018, from http://www.yeniakit.com.tr/haber/erdogandan-abye-tepki-hacli-

ittifaki-kendini-gosterdi-293380.html; “Çelik’ten AB’ye Takvim Tepkisi: Çifte Standart,” Hürriyet,

(February 16, 2018), retrieved February 22, 2018, from http://www.hurriyet.com.tr/dunya/celikten-abye-

takvim-tepkisi-cifte-standart-40744569. - See, Erhan İçener, “Privileged Partnership: An Alternative Final Destination for Turkey’s Integration with the European Union,” Perspectives on European Politics and Society, Vol. 8, No. 4 (2007), pp. 423-424; Beyazıt, “Privileged Partnership: As An Alternative Way to Turkey’s European Union Membership Bid” ; Siret Hürsoy, “On the Edge of the EU: Turkey’s Choice between ‘Privileged Partnership’ and Non-Accession,” Asia Europe Journal, Vol. 15, No. 3 (September, 2017), pp. 319–339.

- “Negotiation Framework: Principles Governing the Negotiations.”

- Cited in İçener, “Privileged Partnership,” p. 423.

- For example see, Carlo Altomonte, Pierre Defraigne, et al. “Le Partenariat Privilégié, Alternative à l’Adhésion,” Robert Schuman Foundation Brochure, Vol. 38, (2006), retrieved January 5, 2018, from http://www.robert-schuman.eu/fr/doc/notes/notes-38-fr.pdf; Robert Del Picchia and Hubert Haenel, “Rapport d’Information fait au Nom de la Délégation pour l’UnionEuropéenne (1) sur la Candidature de la Turquie à l’UnionEuropéenne,” Senat, (April 29, 2004), retrieved January 20, 2018, from http://www.senat.fr/rap/r03-279/r03-2791.pdf; and views expressed by Merkel and other advocates cited in İçener, “Privileged Partnership,” and Beyazıt, “Privileged Partnership.”

- “Negotiation Framework: Principles Governing the Negotiations,” p. 5.

- See, Del Picchia and Haenel, “Rapport d’Information,” pp. 33-38.

- Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg, “Preserving Europe: Offer Turkey a ‘Privileged Partnership’ Instead,” The New York Times, (December 15, 2004), retrieved January 30, 2018, from http://www.nytimes.com/2004/12/15/opinion/preserving-europe-offer-turkey-a-privileged-partnership-instead.html.

- Robert Del Picchia and Hubert Haenel, “Rapport d’Information.”

- Altomonte et al., “Le Partenariat Privilégié, Alternative à l’Adhésion,” pp. 60-74.

- “Merkel Rules out EU Membership for Turkey,” The National, (March 25, 2010), retrieved January

5, 2018, from https://www.thenational.ae/world/europe/merkel-rules-out-eu-membership-for-turkey-

1.549451. - Guttenberg, “Preserving Europe: Offer Turkey a ‘Privileged Partnership’ Instead.”

- Altomonte et al.,“Le Partenariat Privilégié, Alternative à l’Adhésion.”

- Mirel, “European Union-Turkey.”

- “Gümrük Birliği’nin Bedelini Ağır Ödüyoruz,” Sabah, (January 30, 2011), retrieved January 20, 2018, from https://www.sabah.com.tr/ekonomi/2011/01/30/gumruk_birliginin_bedelini_agir_oduyoruz.

- For a summary of the CU decision, see notes of the Turkish Ministry of EU Affairs retrieved January 20, 2018, from https://www.ab.gov.tr/46234_en.html.

- At the extreme, countries such as Mexico, Algeria, and South Africa have even avoided negotiating a deal with Turkey after they signed an agreement with the EU. Information on Turkey’s FTAs is available on the website of the Turkish Ministry of Economy, retrieved January 20, 2018, from https://www.ekonomi.gov.tr/.

- Kemal Kirişçi, “Turkey and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership: Boosting the Model Partnership with the United States,” Brookings, No. 2, (2013), pp. 13-16, retrieved January 20, 2018, from https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Turkey-and-the-Transatlantic-Trade-and-Investment-Partnership.pdf; Serdar Altay “Associating Turkey with the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership: A Costly (Re-) Engagement?” World Economy, Vol. 41, (2018), p. 308, retrieved January 20, 2018, from https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.12533.

- “Evaluation of the EU-Turkey Customs Union (English),” World Bank, (2014), retrieved January 5,

2018, from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/298151468308967367/Evaluation-of-the-EU-

Turkey-customs-union. - “Report of the Senior Officials Working Group (SOWG) on the Update of the EU-Turkey Customs Union

and Trade Relations,” (April 27, 2015), retrieved January 5, 2018, from https://www.ekonomi.gov.tr/. - “Working Document Impact Assessment.”

- “Working Document Impact Assessment,” p. 13.

- “Working Document Impact Assessment,” pp. 21-22.

- The EC does not envision an expansion of the CU to new domains as conventionally understood by “an upgrade of the CU,” but rather negotiating separate FTAs on new areas in addition to CU 1.0.

- “Working Document Impact Assessment,” p. 24.

- “Working Document Impact Assessment,” p. 24.

- “Countries and Regions: Turkey,” European Commission, retrieved January 5, 2018, from http://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/countries/turkey/.

- “Working Document Impact Assessment,” pp. 11-12.

- “Working Document Impact Assessment,” p. 24.

- Altay, “Associating Turkey with the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership,” pp. 326-328.

- “Working Document Impact Assessment,” pp. 23-24, 49-50.

- Gary Clyde Hufbauer, J. Bradford Jensen and Sherry Stephenson, “Framework for the International Services Agreement,” Policy Brief, No PB 12 - 10, (Washington, D.C.: Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2012), p. 17.

- Against a one hundred-page negotiation and impact analysis document issued by the European Commission, the Turkish Ministry of Economy has only responded with a one-pager press release which exclusively summarizes the findings of an impact analysis commissioned from an unknown resource. The one-pager provides no information on the methodology used in arriving at any of the findings, and leaves in the dark several dimensions of the economic impacts of a CU 2.0 on Turkey, such as its effects on Turkish imports. See, “Gümrük Birliği’nin Güncellenmesi Etki Analizi Çalışması Basın Bildirisi,”Ministry of Economy, (January 18, 2017), retrieved January 15, 2018, from https://www.ekonomi.gov.tr/.

- The Ministry also lacks sufficient resources in terms of expertise and experience to negotiate new generation trade issues and rules. The Ministry negotiated and signed comprehensive FTAs only with Korea and Singapore. See, https://www.ekonomi.gov.tr.

- “Working Document Impact Assessment,” pp. 78-81; “The Impact of EU Used Vehicle Imports on Turkey,” Final Report-Extended Version for Otomotiv Sanayii Derneği, (June, 2016).

- “Evaluation of the EU-Turkey Customs Union,” p. 66.

- The Commission explicitly states that during the negotiations it “will aim at a content of” the sustainable development chapter of CETA. See, “Working Document Impact Assessment,” p. 37.

- “Evaluation of the EU-Turkey Customs Union,” pp. 64-65.

- Altay, “Associating Turkey with the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership,” pp. 329-332.

- Serdar Altay, “Derin Entegrasyon ve ‘DTÖ-artı’ Gündemi Işığında Türkiye-AB Gümrük Birliği’nin Kamu Alımlarına Genişletilmesi ve Türkiye’ye Etkileri,” International Congress on Politics, Economic and Social Studies, Vol. 3, (2017).

- Martin Raiser, “The Turkey-EU Customs Union at 20: Time for a Facelift,” Brookings, (March 16, 2015), retrieved February 1, 2018, from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2015/03/16/the-turkey-eu-customs-union-at-20-time-for-a-facelift/.

- Quoted in Mirel, “European Union-Turkey: From an Illusory Membership to a ‘Privileged Partnership.’”

- “Hahn: Stratejik Ortaklığa Yoğunlaşalım,” Deutsche Welle Türkçe, (February 22, 2018), retrieved February 26, 2018, from http://www.dw.com/tr/hahn-stratejik-ortakl%C4%B1%C4%9Fa-yo%C4%9Funla%C5%9Fal%C4%B1m/a-42689640.

- “Erdogan: Turkey ‘Tired’ of EU Membership Process,” Al Jazeera News, (January 6, 2018), retrieved February 26, 2018, from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/01/erdogan-turkey-tired-eu-membership-process-180105213814481.html; “Turkey No Longer Needs EU Membership but Won’t Quit Talks – Erdogan,” Reuters, (October 1, 2017), retrieved February 26, 2018, from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-eu-turkey/turkey-no-longer-needs-eu-membership-but-wont-quit-talks-erdogan-idUSKCN1C61CL.

- “Türkiye ile Gümrük Birliği Müzakereleri Başlatılmalı,” Deutsche Welle Türkçe, (December 9, 2017),

retrieved January 5, 2018, from http://www.dw.com/tr/t%C3%BCrkiye-ile-g%C3%BCmr%C3%BCk-

birli%C4%9Fi-m%C3%BCzakereleri-ba%C5%9Flat%C4%B1lmal%C4%B1/a-41715935.