Introduction

The European Union (EU) is no stranger to migration inflows. The 2015 migration crisis is probably the most serious challenge facing Europe, which, after World War II became a dream destination for millions from the developing world. Nowadays, it still remains “the continent of international migration, with a tenth of the world’s people and a third of the world’s international migrants.”1

In recent decades, migrations from Africa and Asia made the regulation of inflows much more difficult for the EU. In searching for a solution, the EU chose to rely on external players –in exchange for some concessions and support– including governments that did not share its values; such as the government of Muammar Qaddafi in Libya. This in turn gave these players the opportunity to use migration as a weapon against the EU. Kelley Greenfield calls it coercive engineered migration,2 defining it as “cross-border population movements that are deliberately created or manipulated in order to induce (involuntary) political, military, and/or economic concessions from a target state or states.”3

The events in the Middle East in 2010 gave new impetus to migration, exacerbating processes that have been initiated years before. Corruption, high unemployment rates, bad governance, constant violation of human rights, and political repression against the opposition, practiced by secular authoritarian regimes, increased social tensions in Tunisia, Libya, Morocco, Yemen, Egypt, and elsewhere. Brought under the common denominator of the Arab Spring, they followed different directions and had different consequences. In Syria, the Arab Spring was much more than a battle between supporters and enemies of Bashar al-Assad. The Sunni Muslim majority, the president’s Shia Alawite sect, Syrian Kurds, and terrorist organizations such as ISIS, were among the main stakeholders in the national political arena, each with its own agenda and ideas about the future of the country. With Iran and Russia supporting the government, and Turkey, the Western powers and some Gulf states underpinning the opposition, the political landscape became even more complex-international players pursued their own divergent interests that on several occasions had little to do with the aspirations of the local population for peace and the cessation of hostilities. The U.S. actively intervened from September 2014 to September 2015 by supporting the opposition and targeting ISIS militants;4 it armed, trained, and provided military air cover to the anti-government, anti-terrorist opposition. With 2,000 military personnel,5 Russia became involved in September 2015 at the request of the Syrian government, within the framework of long-term cooperation and solidarity with Syria. Despite the fact that the main actors responsible for the conflict are the Syrian government and ISIS, several researchers argue that what was witnessed there was “a proxy war among such contestants as Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Iran, Turkey, the U.S., Russia, and others.”6

According to data collected by the International Organization for Migration, the total number of immigrants and asylum-seekers seeking entry to the EU in 2019 was 123,920

The first signs of the Syrian migration crisis appeared in 2013 and 2014.7 The crisis peaked in 2015 when 1,255,640 first-time asylum applicants crossed EU borders,8 illustrating again “the potential power of unregulated migration to make people and governments feel insecure and under threat.”9 As the EU established firm security measures to thwart migration, this number dropped dramatically afterward. According to data collected by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the total number of immigrants and asylum-seekers seeking entry to the EU in 2019 was 123,920.10 Migrants arrived not only from the battlefields of Syria but also from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Nigeria, and elsewhere.11

Methodological and Conceptual Framework

This paper addresses the following research questions: could coercive engineered migration be used as a hybrid threat? Could a state that is not a source of migration use it as such a threat? If so, which kind of state can do this, and under what conditions is this possible?

We argue that coercive engineered migration can be used as a hybrid threat by a state, even when it is not the source of outflows; that it is possible under conditions of an internal or external conflict in the sending state; that a state-challenger would most probably be an authoritarian state supporting the government of the emigration state. The authors argue that the sound action for Turkey and the EU in the conditions of a crisis like that of 2015, would be to develop a migration diplomacy initiative that could contribute not only to a deal but to a sustainable, mutually beneficial solution for both parties.

Before going further, and with the purpose to shed more light on the views expressed, the main terms implemented –hybridity, hybrid threat, and hybrid war– will be introduced. They are part of the new discourse of war composed of categories as fourth-generation warfare,12 network war,13 compound war,14 new war,15 etc.

In conceptualizing the terms, we apply Ludwig Wittgenstein’s approach of family resemblance, as opposed to the necessary and sufficient condition approach, where a given feature cannot be substituted by another. Wittgenstein illustrates his view with the games, asking the question what is the common between board games, card games, ball games, Olympic Games, and so on, and answering that similarity exists in relationships, procedures, etc.; this kind of similarity he calls ‘family resemblances.’16 Applied to the current research, this would mean that there is no necessary and sufficient condition for some phenomenon to be conceptualized as ‘hybrid.’ It is enough to identify at least two components enlaced by family resemblance as for example military operations and information operations; cyberattacks understood as a malicious and deliberate attempt by an individual or organization to breach the information system of another individual or organization in order to benefit from disrupting the victim’s network and coercive migration;17 economic pressure, and trolling. Combinations can vary. In the military field, hybridity is not a simple sum of several unconventional factors, but much more than that since they support and enhance each other.

Hybrid threats aim to weaken a defender’s power, position, influence, or will, rather than to strengthen those attributes for the attacker. They are not designed to cause direct harm to people, but rather to destabilize the target

If there is a relative consensus in the international academic debate about the nature of hybridity, there is no consent on the character of its components. Militaries grasp the participation of regular armed forces as a needed condition for hybridity, while civil institutions and researchers do not. This disparity is due to the fact that “hybridity” has evolved in two different contexts –military science and political science.18 EU documents, for example, view hybrid threats –one of the terms of the cluster that appeared around ‘hybridity’– “as a mixture of coercive and subversive activities, conventional and unconventional methods (i.e. diplomatic, military, economic, technological), that can be used in a coordinated manner by state or non-state actors to achieve specific objectives while remaining below the threshold of formally declared warfare.”19

On a more practical level, hybrid threats can range from cyberattacks on critical information systems and the disruption of critical services such as energy supplies or financial services, to the undermining of public trust in government institutions or the deepening of social divisions. According to Pawlak, hybrid threats arising from the articulation of different elements include various actions, conditions, and events perceived by states or non-state actors as dangerous in terms of their needs, values, and projects.20

Some emphasize its multifaceted nature, which transforms quickly to adapt to the changing environment.21 Others call attention to the fact that hybrid threat is always “custom-tailored” and serves the needs of a certain actor in a certain situation, giving Russia an example.22 Hybrid threats aim to weaken a defender’s power, position, influence, or will, rather than to strengthen those attributes for the attacker.23 They are not designed to cause direct harm to people, but rather to destabilize the target.24 Through a wide range of means, hybrid threats can target the systemic vulnerabilities of democratic states and institutions, the will of the people, and the decision-making ability at a state or international level.25 From this point of view, hybrid threats have to do with Sun Tzu’s view that “to subdue the enemy without fighting is the acme of skill.”26 Sadowski and Becker point out the agents of hybrid threats defining them as “entities or movements that continually scan the environment for opportunities and threaten to or apply violence to affect the will and psyche of others to achieve their political objectives.”27

For the purposes of this study, we conceptualize hybrid threats as situations or activities that could lead to coercion, where a military component is not necessarily presented and where a flexible exercise of different capabilities, forms, and strategies of a vague and blurred nature might contribute to the success of the challenger. As hybrid threats remain in a gray zone between war and peace, the identification of the challenger is extremely difficult. Thus we do not speak about ‘violence,’ understood as the use of physical force to injure, abuse, damage, or destroy.28 Neither do we mean behaviors involving physical force intended to hurt, damage or kill someone or destroy something.29 We relate hybrid threat with ‘coercion,’ defined as the “ability to get an actor –a state, the leader of a state, a terrorist group, a transnational or international organization, a private actor– to do something it/he/she does not want to do.”30

Accepting that migration has to do with national, regional, and global security, we argue that it can heavily impact the modern system of international relations and foreign policy

Without entering into details about the hybrid war, another term that appeared as a part of the cluster around hybridity, and will be in use here, it is defined as any political act that aims to compel our enemy to do our will; an act, which combines more than one form of violence (but does not include necessary physical or kinetic component) and is directed above all to the destruction of the institutions (through eroding trust and governability), communities (through impeding informed individual and collective choices), and society, threatening it through interference in national decision making process and impact on public opinion.31

A Refugee camp for Syrians in Turkey. November 6, 2019, Kilis, Turkey. Directorate General of Migration Management / AA

A Refugee camp for Syrians in Turkey. November 6, 2019, Kilis, Turkey. Directorate General of Migration Management / AA

Was the mass migration of Syrians to the EU just a collateral result of the conflict or a weapon deliberately engineered by state or non-state actors against the ЕU? Among member states, unregulated migration had already been recognized as a means of coercion and mentioned as a hybrid threat32 in several important documents: “Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council Joint Framework on Countering Hybrid Threats –A European Union Response;”33 “Joint Staff Working Document EU, Operational Protocol for Countering Hybrid Threats;34 (HR, 2016),” Global Strategy (EUGS), and the EU-NATO Joint Declaration of 201635 on increasing collaboration between the two institutions to mention a few. Migration has become an even more sensitive point on the political agenda of the EU and its member states, as far as it raises anew concerns about “sovereignty, citizenship, national security, and identity,”36 as well as the ability of the EU to control its borders and keep its population safe, while ensuring, at the same time, due respect to the rights of migrants. When threat perceptions on sovereignty, citizenship, security, and identity emerge altogether, they can melt and transform into a dangerous cocktail ready to explode at any moment and cause inevitable damage to the European democratic space. This constellation has contributed significantly to the securitization of migration. Each of its components stimulates others: sovereignty –as far as it poses the question of what it means to be part of the EU; citizenship –because it remains the union’s primary integration tool; security –since it is one of the most valuable collective goods in times of crisis; and identity –since it reacted aggressively against statements that it is possible to be European and accept European values without practicing them.37 While the EU migration crisis has been largely discussed in the academic literature, scholars have been surprisingly reluctant to use the concept of hybrid threats to frame the analysis of inflows that have, to a great extent, undermined European authority, unity, and solidarity, and revealed that the EU was not able to elaborate a common security and defense policy or to adopt any collective response.

Underpinnings of the Argument

This paper approaches the issue of migration through the lens of political realism accepting it as a threat to national, regional, and global security. The idea that immigration, particularly irregular immigration, is such a threat is not new. In analyzing specific policy implications, Heisler and Layton-Henry consider the spillover effects of conflicts that lead to forced migration. They argue that the threat of migration arises when a state is unable to respond or to govern due to high numbers of migrants.38 According to Weiner, migrants could be viewed as a threat for a number of reasons: if they create difficulties in diplomatic relations, if they could be considered hostile to the receiving country, and if they are seen as a cultural threat, an economic problem, or as an intended threat sent by countries of origin or transit.39

Accepting that migration has to do with national, regional, and global security, we argue that it can heavily impact the modern system of international relations and foreign policy. Hence, the study of its link with such important questions as peace and war, including hybrid threats, is needed and justified. The fact that “migration policy and flows are a function not only of factors on the unit level but also of international systemic factors, namely, the distribution of power in the international system and the relative positions of states,”40 is a logical assumption in line with the realist theory of international relations. Realism posits that both the sending and receiving state can convert migration into a weapon against the other; i.e., it can be a powerful factor in the inter-state policy.41

This article builds upon the studies by Kelly Greenhill and Gerasimos Tsourapas. Greenhill describes migration as a coercive weapon;42 she argues that coercive engineered migration, grasped as “cross-border population movements that are deliberately created or manipulated in order to induce (involuntary) political, military, and/or economic concessions from a target state or states”43 has been used by several state and non-state actors to achieve their political goals.44 She concludes that there are enough stimuli for actors with more limited resources “to create new and manipulates extant migration crises, at least in part to influence the behavior of (potential) recipient states,”45 and that generation of migrant crises is a unique opportunity, wherein the weaker state has leverage over the stronger one. By doing so the challenging state aims to receive from the target state-certain concessions, as the latter would not want to take the risk of domestic conflict or public dissatisfaction as a result of mass migration. Speaking about Qaddafi’s threats to use a “demographic bomb,” Greenhill calls such efforts “unconventional coercion,”46 which is similar to our concept of “hybrid threat” as defined in this study. Meanwhile, we see unconventional coercion as a component of a hybrid strategy, which, together with other components, is deliberately implemented by state or non-state actors in attaining their geopolitical goals.

Conditionality is an important tool in the EU’s policy of migration externalization, as it shapes the migration policies of candidate countries according to EU rules, norms, and values; and using conditional rewards, incentives, or punishment

Greenhill states that challengers exercising coercive engineered migration can be divided into three: generators, agent provocateurs, and opportunists. Generators directly create or threaten to create, cross-border population movements unless targets concede to their demands. Agent provocateurs do not create crises directly but rather deliberately act in ways designed to incite the generation of outflows by others. Opportunists play no direct role in the creation of migration crises, but simply exploit the existence of outflows generated or catalyzed by others.47

Some researchers reject the use of the metaphor “migration as a mass weapon” with the argument that it “does little to mitigate the instilling of fear and to create a positive image of refugees.”48 The metaphor, indeed, raises important ethical issues. According to some scholars, it relates refugees with weapons of mass destruction; it frames them as “dangerous weapons and leads the audience to think and act on this framing as if refugees are dangerous weapons aimed at them.”49 Then, the question could be stated: is it ethically justifiable to use such a metaphor taking into consideration that in international relations metaphors not just shape the discourse, but the way of thinking?50 We will continue using this metaphor because here it refers to migration, rather than migrants themselves, as a weapon. These are two radically disparate thoughts; migrants are people in need of assistance and support, while migration is a phenomenon that could be used to coerce a state without the knowledge or consent of the migrants themselves. Criticism of the metaphor extends to the security-based approach itself, on the grounds that it securitizes migration and is state-centric. Its adversaries highlight that it “prevents a plausible approach to the global management of migration” and the consolidation of a rights-based51 and cooperation-based approach. We would not share such a view. Realism, like any other theory, has its limitations; however, it does not contradict other approaches. Security (which realism emphasizes) is also a right (emphasized by right based approach) –both for migrants and for the local population. Security issues can be sustainably and effectively arranged only through the broadest international cooperation in order to make the global management of migration possible, as it requires a cooperation-based approach.

There are alternative arguments among academicians on whether Russia is the actor to be blamed for using migrants as a weapon

Tsourapas argues that autocracies employ labor emigration policy in order to enhance regime durability52 and that the interplay between migration and power politics impacts coercive interstate relations as far as, “under certain conditions, weaker states can successfully employ a nonmilitary coercive strategy against more powerful states.”53 In this article, we claim that such regimes, under certain conditions, can use not only labor but any form of migration to strengthen their positions. Moreover, an authoritarian regime can profit from irregular migration even when it is not the source but is an ally or a supporter of the ruling elite of an authoritarian state suffering internal or external conflict.

A Hybrid Challenge for Turkey?

Is the Syrian refugee crisis, which gave rise to the ‘systemic destabilization’54 of the EU, a hybrid threat? The answer might be positive: “The hybrid threat derives from [refugees’] potential ‘weaponization’ by hostile powers.”55 Once started, it might lead to an increase of domestic and international tensions and create dangerous situations of confrontation. Moreover, migration can be weaponized by political actors in order to achieve short or long term goals, both nationally and internationally.”56 It should be mentioned here that migration policy in the EU has always been ‘crucified’ between humanitarian law and the need to protect territorial sovereignty; between rights-based approaches that prioritize legal pathways to immigration and protection of refugees, and the need for border control and management of incoming flows. To find the delicate balance between both is time-consuming and difficult. Under hybrid war, migrants are defenseless, as they are not addressees of international humanitarian law:

If states are not even ‘officially’ involved in a hybrid war, then nor can they be called upon to observe this law. Where it is not clear who the warring parties are, where even state actors proceed by “unconventional” means, the protection of civilians is more easily overlooked than in the case of classical interstate wars. Where destabilization is part of the plan, the people themselves become the target of hostilities.57

Conditionality58 is an important tool in the EU’s policy of migration externalization, as it shapes the migration policies of candidate countries according to EU rules, norms, and values; and using conditional rewards, incentives, or punishment.59 This is why the EU, which gets the maximum benefit from the conditionality principle, intends to keep the massive migration flows at the Turkish border as much as possible and so aims to ensure the internal and external border security of Europe by using the ‘immigration card’ in its diplomatic relations with Turkey. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan reacted, stating that the EU has not fulfilled its part of the migrant deal, despite Turkey’s invaluable contribution to the security of Europe: “We have made invaluable contributions to the security of the entire European continent, particularly to the Balkan countries. However, we did not see the support and humanitarian attitude that we expect from our European friends during this difficult time.”60 Ömer Çelik, former Minister of EU Affairs said that the attacks in Syria had increased the mobility of immigrants to Turkey and that Turkey would no longer be able to keep asylum seekers striving to reach Europe since its immigration capacity is full.61 For some researchers, EU’s migration management and border security strategy, based on giving responsibility to candidate and member states located on the external border, have overtaxed Turkey’s capacity to absorb the growing number of the refugees and have made Turkey vulnerable to ‘hybrid threats,’ which, as said earlier, includes not only military and physical but also unconventional threats.

(L-R) Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, European Commission President Ursula Von der Leyen and Croatia’s Prime Minister Andrej Plenkovic give a press conference in Kastanies, at the Greece-Turkey border, on March 3, 2020, amid a migration surge from neighboring Turkey. NICOLAS ECONOMOU / NurPhoto / Getty Images

(L-R) Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, European Commission President Ursula Von der Leyen and Croatia’s Prime Minister Andrej Plenkovic give a press conference in Kastanies, at the Greece-Turkey border, on March 3, 2020, amid a migration surge from neighboring Turkey. NICOLAS ECONOMOU / NurPhoto / Getty Images

Did Russia Use Syrian Migration as a Weapon during the 2015 Migration Crisis?

On the political scene, the first to discuss Syrian unregulated mass migration as a hybrid threat was Donald Tusk, the President of the European Council from 2014 to 2019. In his address to the European Parliament on the informal meeting of heads of state or government of September 23, 2015, he stated that migrants were being sent to Europe as a campaign of “hybrid warfare” in order to force concessions to its neighbors. Donald Tusk admitted that this is not only a new form of political pressure but “a kind of a new hybrid war, in which migratory waves have become a tool, a weapon against neighbors.”62 He didn’t blame any state explicitly, but limited himself to saying that Europeans should not allow “those who are responsible for this massive exodus, will tell us how to treat refugees.” 63

The view that Russia was behind the EU migration crisis is explicitly associated with U.S. General Philip Breedlove and Senator John McCain. On February 25, 2016, General Breedlove, then Supreme Allied Commander of NATO and the U.S. European Command, gave testimony before the U.S. House of Representatives Armed Services Committee, where he shared his conviction that Russia and Bashar al-Assad’s government were using migration flows as a hybrid tool against the EU. He based his claim on the observations that the arms used by Russians in the Syrian theatre have no military utility but are calculated to make the local population leave: “Together, Russia and the Assad regime are deliberately weaponizing migration from Syria in an attempt to overwhelm European structures and break European resolve.” His conclusion was that Russian wanted to “get [the civil population] on the road, make them a problem for Europe, to bend Europe to the will of where they want them to be.”64 Five days later, Breedlove gave a statement before the Senate Armed Services Committee, saying that Russia has embarked on a campaign to corrupt and undermine targeted NATO countries through a strategy of indirect, or “hybrid warfare,” but provided no evidence beyond his own observations. Senators John McCain and Tom Cotton asked Breedlove if he believed that the Russians were using the refugee issue as a means to break up the EU and NATO; in both cases he was positive.65 In 2016, McCain blamed Russian President Vladimir Putin for seeking “to exacerbate the refugee crisis and use it as a weapon to divide the transatlantic alliance and undermine the European project.”66

Diplomatic factors play an important role in the process of migration management, and the implementation of migration policy alongside ethical concerns, human rights-based factors, and geopolitical positions

Despite the international reputation of Senator McCain, only a few media outlets echoed his views. Among them, The Economist published an article stating that Russia might have been using refugees as a weapon against the EU and Turkey. The magazine quoted a report of the International Crisis Group, saying that “there was nothing indiscriminate about the bombing of civilian areas and infrastructure, including schools and hospitals, which had been systematically destroyed to terrify civilians into leaving. Some media outlets mentioned accusations of Western diplomats against Russia’s president for ‘weaponizing’ refugees to threaten Europe and punish Turkey.”67 Quoting a UN report, Reuters said that Syrian and Russian planes had carried out deadly aerial strikes on schools, hospitals, and markets in Idlib province, causing one million civilians to flee.68

In the academic literature, Julia Himmrich, one of the few scholars dealing with the weaponization of migration, asked “if we want to identify whether Russia used migration flows as a hybrid threat, we have to answer first, did it something that caused such a large-scale migration and second, did its actions significantly worsened the migrant crisis in the EU?”69 Hans Schoemaker added two more criteria: “whether Russia deliberately targeted civilian populations in Syria, and whether it was with the intent to exacerbate the refugee crisis resulting from Syria’s civil war and to target the EU and its member states?”70 All these questions seem valid except for the first one asked by Schoemaker. This is because Russia may still use migration as a hybrid threat even if it did not deliberately target the civil population; in this case, it would be a state-opportunist, which takes profit from the given circumstances.

There are alternative arguments among academicians on whether Russia is the actor to be blamed for using migrants as a weapon. Anthony N. Celso, who argues that each of the players in the Syrian political arena committed atrocities,71 echoes Greenhill’s observation that “all sides in the Syrian civil war have, to some extent, strategically engineered mass movements of civilians into and away from their areas of territorial control.”72 Celso’s conclusion is that Russia is not the only partly responsible for outflows to the EU if is responsible at all. Schoemaker rejects the link between the refugee crisis and Russian arguing that there is no coercion without demands, and there have not been any, at least not publicly acknowledged. His conclusion is that the displacements “insofar as deliberate may fit Greenhill’s model, but their use as a weapon against the EU is shown to be an unlikely motive.”73 Taking the opposite view, Viljar Veebel et al. describe Russia’s actions as a de facto “hybrid war.” This is because they argue, Russia never took the opportunity to de-escalate the conflict; it repeatedly used its veto power to block the UN Security Council’s resolutions;74 it produced fake news about refugees and their destiny in EU countries; and finally, it arranged the provocation of the border between Russia and Finland in order to check Finnish readiness to successfully deal with refugees. In a 2020 article, Veebel acknowledges the arguments to the contrary, but still points out the fact that migration waves from Syria exploded in numbers particularly after the conflict in Syria became internationalized, and that Russia’s support for the Assad regime led to conflict aggravation.75 In order to resolve the dilemma, Veebel introduces the term “hybrid aggression,” defined as “aggression as hostile or violent behavior, or an overall readiness to attack or confront.”76 He mentions two more features: the legitimation of the act by the aggressor and the lack of awareness of the victim that it is under attack. Veebel concludes that it is in the best interests of the Western countries “to constantly assess the situation case by case, and to take active countermeasures to avoid massive migration flows (most likely to the EU), as soon as it becomes obvious that Russia has targeted some countries.”77 It is important to note that what Veebel calls hybrid aggression is indeed a hybrid threat –a term already defined in this text.

Indicators and Cases

In order to examine the formulated hypothesis, namely that coercive engineered migration can be used as a hybrid threat by a state, even when it is not the source of outflows; that such use is possible under conditions of an internal or external conflict in the sending state; that a state-challenger would most probably be an authoritarian state supporting the government of the emigration state, the 2015 EU refugee crisis and the actions of Russia during it have been chosen. Before going further, an explanation of this choice is needed. First, some actions of Russia have been recognized as a source of hybrid threats by the EU as for example coercive diplomacy, fake news, and cyber-attacks against critical electoral infrastructure. In order to address Russia’s disinformation campaigns, the East StratCom Task Force was settled.78 At the same time, NATO, in 2018 issued the report “Countering Russia’s Hybrid Threats: An Update,” where it is stated that Russia’s hybrid warfare primarily targets the Euro-Atlantic community and the countries in the ‘grey zone’ between NATO/EU and Russia.79 Finally, Russia has already been using hybrid threats against Turkey; as for example the economic sanctions on Turkey including a ban on tourism, agricultural product, suitcase trading, international contracts, and direct investments, targeting Turkey supported rebels and Syrian Turks (Turkomans), and by supporting Assad’s regime and PYD/YPG which has carried out terrorist attacks in Turkey.80

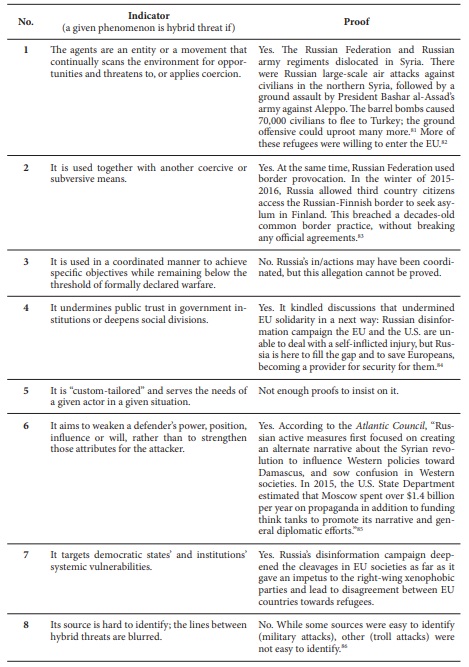

We will consider that coercive engineered migration is used as a hybrid threat if it covers all or most of the next criteria: the agents are an entity or a movement that continually scan the environment for opportunities and threatens to, or applies coercion; it is used together with another coercive or subversive means; it is used in a coordinated manner to achieve specific objectives while remaining below the threshold of formally declared warfare; it undermines public trust in government institutions or deepens social divisions; it is ‘custom-tailored’ and serves the needs of a given actor in a given situation; it aims to weaken a defender’s power, position, influence, or will, rather than to strengthen those attributes for the attacker; it targets democratic states’ and institutions systemic vulnerabilities; its source is hard to identify; the lines between hybrid threats are blurred.

Table 1: Indicators and Proofs of Hybrid Threats

Source: Compiled by the authors

Source: Compiled by the authors

Table 1 shows that Russian activities cover some, but not all indicators. There are agents –entities, or a movement that continually scans the environment for opportunities and threatens to or applies coercion. These are Russian military regiments in Syria, whose actions contribute to migration inflows to Turkey and the EU. They are used together with other coercive tools as for example, the provocation on the border with Finland. Russia aims to weaken a defender’s power, position, influence, or will, rather than to strengthen those attributes for the attacker –it will not destroy the EU solidarity but is able to erode the confidence in them waking up the dangerous illusion that it will substitute the EU and NATO as the security provider for some East European countries. It aims to weaken power, position, influence, or will, rather than to strengthen those attributes for the attacker, both in the case of the EU and Turkey. At the same time, there are not enough proofs to insist that these actions are coordinated; that they are ‘custom-tailored’ and finally, the sources of some attacks were difficult to be identified.

Turkey and the EU: A Difficult Path to Partnership

Acknowledging that Syrian migration is a threat both for EU and Turkey, on March 18, 2016, the European Council and the Turkish authorities released the EU-Turkey Statement, an expression of their will to foster cooperation in order to stop unregulated migration flows to EU countries. The main features of the agreement included the following: the return of irregular migrants who crossed from the Turkish to the Greek border to Turkey as of March 20, 2016; acceleration of the Visa Liberalization Roadmap adopted on December 13, 2016, and lifting of the visa requirements for Turkish citizens in all EU member states by the end of June 2016; acceleration of the allocation process of the first part of the €3 billion project-based financial resource to meet the needs of Syrians in Turkey within the framework of the Turkey-EU Migration Action Plan; transfer of an additional €3 billion in funding to Turkey by the end of 2018 after the initial €3 billion have been used, etc.87 As of March 18, 2016, major steps had been taken to prevent irregular migration and human smuggling. Turkey stated that it has spent around €40 billion from its own resources and is hosting 3.6 million Syrians–more than any other country in the world–while the EU has only paid €2.2 billion out of the €6 billion it had promised to pay for improving the living conditions of Syrians living in Turkey.88

The fragile Turkey-EU deal reveals an important dichotomy for the future of relations between the two parties. The deal triggered a debate regarding the impact of the deal on Turkey-EU relations –whether it would make the existing relationship worse or if it is an opportunity to invigorate the longstanding stagnancy of ascension negotiations.89 While some argued that it would bring a new dynamic to the relations and present significant gains toward re-establishing cooperation between the parties, others feared that it would worsen the existing relationship due to its high costs and the obstacles encountered within the implementation and bargaining process.90

The Turkey-EU deal, by mentioning the promises that both sides must fulfill, has given rise to the understanding that both parties can resolve their major differences concerning Syrian migration through bargaining and negotiations

Inasmuch as the weaponizing of migration by Russia confronts both Turkey and the EU with uncertainties, the deal was potentially the cornerstone for mutual interdependence and diplomatic compromise, despite the difficulties and issues encountered in the implementation process. Diplomatic factors play an important role in the process of migration management, and the implementation of migration policy alongside ethical concerns, human rights-based factors, and geopolitical positions. According to Adamson and Tsourapas, migration policy includes both the strategic use of migration movements for acquiring other aims and the use of diplomatic methods.91 Following this logic, it could be said that migration diplomacy is a bargaining chip between the EU and transit and sending states, that enables them to improve their economic and diplomatic relations.92 Moreover, diplomatic factors provide an opportunity to incentivize reform for host states and take into consideration the international and regional interests driving the migration policy choices of non-EU receiving states.93 The Turkey-EU deal, by mentioning the promises that both sides must fulfill, has given rise to the understanding that both parties can resolve their major differences concerning Syrian migration through bargaining and negotiations.

The two bargaining approaches encountered in the execution of migration diplomacy are zero-sum and positive-sum logic. According to zero-sum logic, which is based on absolute gains, only one side is expected to gain benefits and advantages. In positive-sum logic, which focuses on mutual gains, both parties are expected to benefit even though the degree of benefit to each actor is different. This was the case of the 2016 EU-Turkey deal. EU sought to contain mass immigration movements at the EU’s external borders through the promise of visa-free travel for Turkish citizens, the opening of new chapters, upgrading the customs union, and improving living conditions in Syria.

Being far from solving all their differences, the EU and Turkey showed their will to implement a positive-sum approach. In the recent EU-Turkey meeting, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan said he sees Turkey as part of Europe, but stressed that Ankara will not give in to ‘attacks’ and ‘double standards,’ amid months of tensions with Brussels.94 He also expressed the conviction of the Turkish party that “we do not believe that we have any problems with countries or institutions that cannot be solved through politics, dialogue, and negotiations.”95 Without any doubt, this should be the approach to the management of the refugee flows.

Conclusions

The refugee crisis reached its highest level in 2015 when more than a million people arrived in Europe in one of the biggest migration crises the EU has ever confronted. The crisis increased the disagreements between the EU and Turkey; both parties intended to resolve it through negotiations and to some extend have been successful. One of the wrong steps in the process was that they claimed responsibility from each other only and didn’t pay sufficient attention to the probability that both might be victims of a hybrid threat, whose source is a third party or parties. Our conclusion is that probably Russia does not develop a full-scale hybrid war against the EU and Turkey, but as far as it has developed and implemented some hybrid threats will be described and analyzed by other authors, its maneuvers on the international stage should be carefully observed. Russia has the resources, the experience, and the motivation to use hybrid threats, and the fact that its acts are rather an opportunist does not change their nature.

Turkey and the EU, by considering the costs and benefits in balance, should use their renewed diplomatic engagement to preserve and strengthen their cooperation on immigration

Our initial hypothesis was that coercive engineered migration can be used as a hybrid threat by a state, even when it is not the source of outflows; that it is possible under conditions of an internal or external conflict in the sending state; that a state-challenger would most probably be an authoritarian state supporting the government of the emigration state. In this paper, we decided to analyze the role of Russia as a source of hybrid threats for the relations between the EU and Turkey. Our general conclusion is that there are not enough proves to insist that Russian President Putin has deliberately used the Syrian migration for such purposes.

It was deduced, however, that some circumstances should convince us that a strict vigilance of Russian foreign policy and of the use of hybrid threats as one of its tools is needed. First, the Russian Federation has been already using hybrid threats against the EU and Turkey. They were not implemented to worsen their relationships but successfully achieved other purposes. EU and NATO, whose member is Turkey, have taken respective measures for protecting themselves. Third, Russia has a certain responsibility for the Syrian migration flows because together with Bashar al-Assad’s government and through indiscriminate bombing of civilians made huge populations to fled, causing in this way a deep humanitarian crisis. Moreover, Russia, as a member of the Security Council, never proposed constructive measures for a peaceful solution to the Syrian problem, and systematically rejected any intention in this direction –from 2011 until the end of 2019 Russia vetoed 14 resolutions presented by other countries. 96 Last, but not least, the Russian disinformation war has been partly successful in creating problems among the EU countries concerning refugees undermining the EU solidarity based on ethnic, cultural, and political homogeneity, and weakening the EU’s power. Russia has followed a strategy that goes beyond the liberal values of Europe, aiming at redesigning Europe in a more conservative and traditional way. The probability that such an information war can worsen the relationships between the EU and Turkey cannot be excluded.

Policy Recommendations

Turkey, by hosting the largest number of refugees in the world (including over 3.5 million registered Syrians and over 365,000 persons from other nations), and the EU, dreamed as the final destination by most immigrants has become the most affected by Syrian migration. The chance of repetition of this situation cannot be excluded. Taking this ontological reality as a starting point, the next policy recommendations could be given:

Although the Turkey-EU Statement signed in 2016 brings about a number of ups and downs in terms of the reconciliation of the parties, it also unveils that migration diplomacy through issue-linkages will play a more important role in Turkey-EU relations in the near future and protect them against hybrid threats whose source is a third party.

The issue of Syrian mass migration reveals a chance for the development of Turkey-EU relations and obliges responsibility sharing on the axis of understanding ‘governance’ at the global level

Turkey and the EU, by considering the costs and benefits in balance, should use their renewed diplomatic engagement to preserve and strengthen their cooperation on immigration. Mutually beneficial issue-linkages may lead to quick policy changes and might be an important step in establishing a consistent, common, benefit-oriented, and sustainable migration management strategy in the long term.

The issue of Syrian mass migration reveals a chance for the development of Turkey-EU relations and obliges responsibility sharing on the axis of understanding ‘governance’ at the global level. As no state can act alone in dealing with massive migration movements, there is a clear need for global migration governance, which necessitates intensifying international cooperation around the issue of migration. The goal should be far-reaching policies that address the fundamental reasons for refugee movements and establish peace talks related to conflict zones inasmuch as the protection of refugees creates a global public good.

Endnotes

1. Philip L. Martin, “Viewpoint: Europe’s Migration Crisis: An American Perspective,” Migration Letters, Vol. 13, No. 2 (2016), pp. 307-319.

2. Kelly M. Greenhill, Weapons of Mass Migration: Forced Displacement, Coercion, and Foreign Policy, (New York: Cornell University Press, 2010), pp. 12-13.

3. Kelly M. Greenhill, “Migration as a Coercive Weapon,” in Kelly M. Greenhill and Peter Krause (eds.), Coercion: The Power to Hurt in International Politics, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), p. 204.

4. Yurii Punda, Vitalii Shevchuk, and Viljar Veebel, “Is the European Migrant Crisis Another Stage of Hybrid War?” Sõjateadlane, 13, (2019), pp. 116-136.

5. Hugo Spalding, “Russia’s False Narrative in Syria,” Institute for The Study of War, (December 1, 2015), retrieved December 28, 2020, from http://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russias-false-narrative-syria-december-1-2015.

6. Peter Roell, “Migration: A New Form of Hybrid Warfare?” ISPSW Strategy Series: Focus on Defense and International Security, No. 42 (2016), p. 5.

7. Viljar Veebel and Raul Markus, “Europe’s Refugee Crisis in 2015 and Security Threats from the Baltic Perspective,” Journal of Politics and Law, Vol. 8, No. 4 (2015), pp. 254-262.

8. “Asylum Applicants in the EU,” Eurostat, (2015), retrieved December 13, 2020, from http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/news/themes-in-the-spotlight/asylum2015.

9. Kelly M. Greenhill, “Open Arms Behind Barred Doors: Fear, Hypocrisy and Policy Schizophrenia in the European Migration Crisis,” European Law Journal, Vol. 22, No. 3 (May 2016), pp. 317-332.

10. Mara Bierbach, “Migration to Europe in 2019: Facts and Figures,” Info Migrants, (December 20, 2019), retrieved January 10, 2021, from https://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/21811/migration-to-europe-in-2019-facts-and-figures#:~:text=A%20total%20of%20105%2C425%20migrants,(as%20of%20December%2019).&text=The%20Central%20Mediterranean%20region%20saw,24%2C815%20people%20arrived%20that%20way.

11. “Asylum Applicants in the EU,” Eurostat, (2016), retrieved December 16, 2020, from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/news/themes-in-the-spotlight/asylum2016.

12. William S. Lind, Keith Nightengale, John F. Schmitt, Joseph W. Sutton, and Gary I. Wilson, “The Changing Face of War: Into the Fourth Generation,” Marine Corps Gazette, (1989), pp. 22-26.

13. John Arquilla and David Ronfeldt, “Cyberwar Is Coming!” Comparative Strategy, Vol. 12, No. 2 (Spring 1993), pp. 141-165.

14. Thomas Huber, Compound Warfare: That Fatal Knot, (U.S. Army Command and General Staff College Press, 2002).

15. Mary Kaldor, New and Old Wars: Organized Violence in a Global Era, (California: Stanford University Press, 2012), p. 97.

16. Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations, (Chicago: John Wiley & Sons, 2009), pp. 66-67.

17. “What Are the Most Common Cyber Attacks?” CISCO, retrieved December 26, 2020, from https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/products/security/common-cyberattacks.html.

18. Teodor Frunzeti and Cristian Barbulescu, “Conceptualizing Hybrid Threats-An Essential Phase in the Setting of Strategic Options for Counteraction,” International Scientific Conference “Strategies XXI,” Strategic Changes in Security and International Relations, Vol. 2, (2018), retrieved December 26, 2020, from https://search.proquest.com/openview/a2be1bb77a522728d4d52388b1e89883/1.pdf?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2026346, pp. 1-11.

19. “Joint Framework on Countering Hybrid Threats: A European Union Response,” European Commission, retrieved November 24, 2020, from eur-lex.europe.eu/legal content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:5216JC0018&from=en, p. 2.

20. Patryk Pawlak, “Understanding Hybrid Threats,” European Parliamentary Research Service, (June 24, 2015), retrieved October 28, 2020, from https://epthinktank.eu/2015/06/24/understanding-hybrid-threats/.

21. Petre Dutu, Ameninţări Asimetrice Sau Ameninţări Hibride: Delimitări Conceptuale Pentru Fundamentarea Securităţii Şi Apărării Naţionale, (Bucureşti: Editura Universităţii Naţionale de Apărare, 2013), p. 48. Quoted by Ionuţ Alin Cîrdeı, “Countering the Hybrid Threats,” Revista Academie, Forţelor Terestre, Vol. 2, No. 82 (2016), p. 113.

22. Eitvydas Bajarūnas, “Addressing Hybrid Threats: Priorities for the EU in 2020 and Beyond,” European View, Vol. 19, No. 1 (2020), pp. 62-70.

23. Frank J. Cilluffo and Joseph R. Clark, “Thinking about Strategic Hybrid Threats: In Theory and in Practice,” PRISM, No. 1 (2012), pp. 47-63.

24. Victor Pareja Navarro, “Hybrid Threats: New Technologies as an Instrument of War,” United Explanations, (January 15, 2020), retrieved October 19, 2020, from https://unitedexplanations.org/english/2020/01/15/hybris-threats-new-technologies-as-an-instrument-of-war/.

25. “Hybris Threats,” The European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats, retrieved March 15, 2020, from https://www.hybridcoe.fi/hybrid-threats/.

26. Sun Tzu, The Art of War, translated by Lionel Giles, (November 1, 2007), retrieved October 10, 2020, from http://classics.mit.edu/Tzu/artwar.html.

27. David Sadowski and Jeff Becker, “Beyond the ‘Hybrid’ Threat: Asserting the Essential Unity of Warfare,” Small War Journal, (2010), pp. 1-13.

28. Merriam-Webster Dictionary, retrieved December 9, 2020, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/violence.

29. Oxford Dictionary, retrieved December 23, 2020, from https://www.lexico.com/definition/violence.

30. Robert Art and Kelly Greenhill, “Coercion: An Analytical Overview,” in Kelly M. Greenhill and Peter

Krause (eds.), Coercion: The Power to Hurt in International Politics, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), pp. 3-33.

31. Yavor Raychev, “Lawfare as a Form of Hybrid War: The Case of Bulgaria: An Empirical View Studia Politica,” Romanian Political Science Review, 20, No.2 (2020), рр. 245-270.

32. Roell, “Migration-A New Form of “Hybrid Warfare?”; Nenad Taneski, “Hybrid Warfare: Mass Migration As A Factor for Destabilization of Europe,” Contemporary Macedonian Defense (Sovremena Makedonska Odbrana), Vol. 16, No. 30 (2016), pp. 73-84.

33. “Joint Communication to The European Parliament and the Council Joint Framework on Countering Hybrid Threats,” European Commission, (2016).

34. “Joint Staff Working Document EU Operational Protocol for Countering Hybrid Threats ‘EU Playbook,’” European Commission, retrieved December 25, 2020, from https://www.statewatch.org/media/documents/news/2016/jul/eu-com-countering-hybrid-threats-playbook-swd-227-16.pdf.

35. “EU-NATO Cooperation: Council Adopt Conclusions to Implement Joint Declaration,” Council of the EU, (Washington: Press Release, 2016).

36. James F. Hollifield, “Migration and International Relations,” in Marc R. Rosenblum and Daniel J. Tichenor (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the Politics of International Migration, (UK: Oxford University Press, 2012), p. 347.

37. Hollifield, “Migration and International Relations,” p. 347.

38. Martin O. Heisler and Zig Layton Henry, “Migration and the Links between Social and Societal Security,” in Waever et al. (eds), Migration and the New Security Agenda in Europe, (London: Pinter Publisher, 1993).

39. Myron Weiner, “Security, Stability, and International Migration,” International Security, Vol. 17, No. 3 (1992), pp. 91-126.

40. Hollifield, “Migration and International Relations,” pp. 345-382.

41. Gerasimos Tsourapas, “Labor Migrants as Political Leverage: Migration Interdependence and Coercion in the Mediterranean,” International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 62, No. 2 (2018), pp. 383-395.

42. Greenhill, “Migration as a Coercive Weapon,” p. 204.

43. Greenhill, Weapons of Mass Migration, pp. 12-13.

44. Greenhill, “Migration as a Coercive Weapon,” p. 204.

45. Greenhill, “Migration as a Coercive Weapon,” p. 206.

46. Greenhill, “Using Refugees as Weapons,” The New York Times, (April 21, 2011), retrieved June 18, 2020, from https://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/21/opinion/21iht-edgreenhill21.html?_r=1.

47. Greenhill, “Open Arms Behind Barred Doors,” pp. 317-332.

48. Lev Marder, “Refugees Are not Weapons: The ‘Weapons of Mass Migration’ Metaphor and Its Implications,” International Studies Review, 20 No. 4 (2018), pp. 576-588.

49. Marder, “Refugees Are Not Weapons,” pp. 576-588.

50. Paul Chilton and George Andlakoff, Foreign Policy by Metaphor, Language and Peace, (Aldershot, UK: Dartmouth Publishing Company, 1995), pp. 37-61.

51. Can Ünver, “Migration in International Relations: Towards a Rights-Based Approach with Global Compact?” Perceptions, Vol. 22, No. 4 (2017), pp. 85-102.

52. Gerasimos Tsourapas, The Politics of Migration in Modern Egypt: Strategies for Regime Survival in Autocracies, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), p. 1.

53. Tsourapas, “Labor Migrants as Political Leverage,” pp. 383-395.

54. Yuriy Danyk, Maryna Semenkova, and Piotr Pacek, “The Conflictogenity of Migration and Its Patterns During the Hybrid Warfare,” Torun International Studies, Vol. 12, No. 1 (2019), pp. 61-73.

55. Daniel Fiott and Roderick Parkers, “Protecting Europe the EU’s Response to Hybrid Threats,” European Union Institute for Security Studies, Chaillott Paper, No. 151 (April 2019), retrieved June 15, 2020, from https://www.iss.europa.eu/sites/default/files/EUISSFiles/CP_151.pdf, p. 11.

56. Julia Himmrich, “A ‘Hybrid Threat’? European Militaries and Migration,” Dahrendorf Forum IV, Working Paper No. 2 (LSE Ideas, April 25, 2018), retrieved July 7, 2020, from https://www.dahrendorf-forum.eu/publications/europe_military_migration/.

57. Elke Tießler-Marenda, “Refugee Movements as a Consequence of Hybrid Wars,” Ethics and Armed Forces Controversies in Peace Ethics and Security Policy, 2 (Fall 2015), retrieved July 10, 2020, from http://www.ethikundmilitaer.de/en/full-issues/20152-hybrid-warfare/tiessler-marenda-refugee-movements-as-a-consequence-of-hybrid-wars/.

58. The conditionality principle can be expressed as the obligations and responsibilities that countries applying to become members of the EU must fulfill, before obtaining the EU membership. Under the principle of conditionality, candidate countries are expected to comply with EU standards and the ‘Copenhagen criteria’ adopted at the Copenhagen Summit in 1993.

59. Violeta Moreno-Lax and Martin Lemberg-Pdersen, “Externalizing EU Migration Control while Ignoring the Human Rights of Migrants: Is There Any Room for the International Responsibility of European States?” Questions of International Law, Vol. 56, (February 2019), p. 5.

60. “Europe Hasn’t Fulfilled Migrant Deal Despite Turkey’s ‘Invaluable Contribution’: Erdoğan,” Daily Sabah, (July 9, 2019), retrieved October 5, 2020, from https://www.dailysabah.com/eu-affairs/2019/07/

09/europe-hasnt-fulfilled-migrant-deal-despite-turkeys-invaluable-contribution-erdogan.

61. Mümin Altaş and Özcan Yıldırım, “AK Parti Sözcüsü Çelik: Artık Mültecileri Tutabilecek Durumda Değiliz,” Anadolu Agency, (February 28, 2020), retrieved October 07, 2020, from https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/politika/ak-parti-sozcusu-celik-artik-multecileri-tutabilecek-durumda-degiliz/1747670.

62. “Address by President Donald Tusk to the European Parliament on the Informal Meeting of Heads of State or Government,” European Council, (October 6, 2015), retrieved October 10, 2020, from http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2015/10/06/tusk-address-european-parliamentinformal-euco-september/.

63. “Address by President Donald Tusk to the European Parliament on the Informal Meeting of Heads of State or Government.”

64. “Document 2016 U.S. European Command Posture Statement,” USNI News, retrieved October 10, 2020, from https://news.usni.org/2016/02/26/document-2016-u-s-european-command-posture-statement.

65. “Hearing before the Committee on Armed Services,” United States European Command, (March 1, 2016), retrieved October 10, 2020, from https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-114shrg25644/html/CHRG-114shrg25644.htm.

66. Ron Synovitz, “Is Russia ‘Weaponizing Refugees’ to Advance Its Geopolitical Goals?” Radio Free Europe, (February 19, 2016), retrieved from https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-weaponizing-syrian-refugees-geopolitical-goals/27562604.html.

67. “Vladimir Putin’s War in Syria: Why Would He Stop Now?” The Economist, (February 20, 2016), retrieved September 8, 2020, from https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2016/02/20/why-would-he-stop-now.

68. Stephanie Nebehay, “Deadly Syrian, Russian Air Strikes in Idlib Amount to War Crimes, U.N. Says,” Reuters, (July 7, 2020), retrieved September 9, 2020, from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-syria-security-un-warcrimes/deadly-syrian-russian-air-strikes-in-idlib-amount-to-war-crimes-un-says-idUSKBN2481NF?utm_source=iterable&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=1344259_.

69. Hans Schoemaker, “Allegations of Russian Weaponized Migration against the EU with the Blackest Intention,” JaarGang 188, Vol. 7, No. 8 (February 2019), p. 361.

70. Schoemaker, “Allegations of Russian Weaponized Migration against the EU,” p. 361.

71. Anthony N. Celso, “Superpower Hybrid Warfare in Syria,” MCU Journal, 9, No. 2 (2019), pp. 92-11.

72. Kelly M. Greenhill, “Demographic Bombing: People as Weapons in Syria and Beyond,” Foreign Affairs, (December 17, 2015), retrieved October 10, 2020, from https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2015-12-17/demographic-bombing.

73. Schoemaker, “Allegations of Russian Weaponized Migration against the EU,” p. 366.

74. Yurii Punda et al., “Is the European Migrant Crisis Another Stage of Hybrid War?” p. 130.

75. Viljar Veebel, “Is the European Migration Crisis Caused by Russian Hybrid Warfare?” Journal of Politics and Law, 13, No. 2 (2020), p. 44.

76. Veebel, “Is the European Migration Crisis Caused by Russian Hybrid Warfare?” p. 44.

77. Veebel, “Is the European Migration Crisis Caused by Russian Hybrid Warfare?” p. 44.

78. “Questions and Answers about the East StratCom Task Force,” European Union External Action, (December 5, 2018), retrieved October 9, 2020, from https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/2116/- questions-and-answers-about-the-east-stratcom-task-force_en.

79. Lord Jopling, “Countering Russia’s Hybrid Threats: An Update,” NATO Parliamentary Assembly, (October 2018), pp. 1-21.

80. Oktay Bingöl, “Hybrid War and Its Strategic Implications to Turkey,” Akademik Bakış, Vol. 11, No. 21 (Winter 2017), pp. 1-26.

81. George Soros, “Refugee Crisis: Putin’s Russia in Race with EU to See Which Will Collapse First,” Irish Examiner, (February 16, 2015), retrieved October 10, 2020, from https://www.irishexaminer.com/opinion/commentanalysis/arid-20381172.html.

82. “Europe,” UNHCR, retrieved October 12, 2020, from https://www.unhcr.org/europe.html. https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/2116/-questions-and-answers-about-the-east-stratcom-task-force_en.

83. atri Pynnöniemi and Sinikukka Saari, “Hybrid Influence: Lessons from Finland,” NATO Review, (June 28, 2017) retrieved October 10, 2020, from https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2017/06/28/hybrid-influence-lessons-from-finland/index.html.

84. Antonios Nestoras, “How the Kremlin Is Manipulating the Refugee Crisis: Russian Disinformation As a Threat to European Security,” Institute of European Democrats, (January 2019), pp.1-15.

85. Alami Mona, “Russia’s Disinformation Campaign Has Changed How We See Syria,” Atlantic Council, (October 08, 2020), retrieved from https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/syriasource/russia-s-disinformation-campaign-has-changed-how-we-see-syria/.

86. Todd C. Helmus, Elizabeth Bodine-Baron, Andrew Radin, Madeline Magnuson, Joshua Mendelsohn, William Marcellino, Andriy Bega, and Zev Winkelman, Russian Social Media Influence: Understanding Russian Propaganda in Eastern Europe, (California: RAND Corporation, 2018).

87. “EU-Turkey Statement 18 March 2016,” Council of the European Union, (May 18, 2020) retrieved October 10, 2020, from https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/03/18/eu-turkey-statement/.

88. Fahrettin Altun, “Response: Turkey Is Helping, Not Deporting Syrian Refugees,” Foreign Policy, (August 23, 2019), retrieved March 20, 2020, from https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/08/23/turkey-is-helping-not-deporting-syrian-refugees-erdogan-turkish-government-policy/; “EU: Sum Paid for Refugees in Turkey Must Be Clarified,” Anadolou Agency, (September 10, 2019), retrieved March 25, 2020, from https://www.aa.com.tr/en/europe/eu-sum-paid-for-refugees-in-turkey-must-be-clarified/1578213.

89. Seçil Paçacı Elitok, “Three Years On: An Evaluation of the EU-Turkey Refugee Deal,” MireKoc Working Papers, (2019), p. 10.

90. Elitok, “Three Years On.”

91. Fiona B. Adamson and Gerasimos Tsourapas, “Migration Diplomacy in World Politics,” International Studies Perspectives, Vol. 20, No. 20 (2019), p. 117.

92. Kelsey P. Norman, “Migration Diplomacy and Policy Liberalization in Morocco and Turkey,” International Migration Review, Vol. 20, No. 10 (2020), p. 5.

93. Kelsey P. Norman, “Migration Diplomacy and Policy Liberalization in Morocco and Turkey,” International Migration Review, Vol. 54, No. 4 (2020), pp. 1158-1183.

94. Jacopo Barigazzi, “Erdoğan Insists Turkey Is Part of Europe, But Won’t Tolerate ‘Attacks,’” Politico, (November 22, 2020), retrieved March 28, 2020, from https://www.politico.eu/article/erdogan-insists-turkey-part-europe-wont-tolerate-attacks/.

95. “Erdoğan Insists Turkey Is Part of Europe, But Won’t Tolerate ‘Attacks.’”

96. “Русия блокира Хуманитарна Помощ за Сирия с вето в Съвета за Cигурност,” NewsBg, (December 21, 2019) retrieved March 28, 2020, from https://news.bg/int-politics/rusiya-blokira-humanitarna-pomosht-za-siriya-s-veto-v-saveta-za-sigurnost-1.html.