Starting in November 2010, the Arab world experienced a comprehensive and profound shock, which has been dubbed as the “Arab Spring.” It took various forms, ranging from revolutions that unseated powerful regimes and rulers who thought their hold on power was secure, to vocal protests against the existing order and calls to replace it with something new.

One of the main sources of the public protests and the desire to alter the status quo was the Arab peoples’ comparison of their condition with their surroundings –both in the world at large and in the non-Arab Muslim Middle East– meaning Turkey and Iran, both of which are regional powers.1 Systematic comparisons, conducted in broadcast and print media, at academic and public conferences and gatherings, and even in official reports issued inside and outside the Arab world, juxtaposed the meager achievements of the Arab countries with the more substantial accomplishments of humanity at large, the developed countries, and neighboring countries such as Turkey and Iran.

This contrast between the puny achievements of the Arab states and society, on the one hand, and the impressive gains of Turkey and Iran, on the other, was evident in various fields, ranging from culture, science, and society to technology, industry, the military and defense establishment, and on to governmental stability, democracy, and civic life. Of all the countries in the world, Turkey and Iran were singled out for special attention in these comparisons. Both are Muslim countries that have experienced conquest, colonialism, and Western attempts to subdue them; as a result, a broad spectrum of those promoting change in the Arab world viewed these countries as objects for study and emulation. In fact, the desire to register the same achievements (real or imagined) as Iran and Turkey was a major ingredient of the unrest in much of the Arab world during the Arab Spring, and this desire contributed significantly to the waves of protest against the existing order during the first stage of the Arab Spring from 2010-2012.

This article will shed light on the discourse in the Arab world about taking Turkey and Iran as models for emulation, and on these models’ contribution to the demands for change raised by diverse public figures, journalists, and scholars and deemed to be realistic and appropriate for the Arab world.

Theoretical Background: Diffusion as an Agent of Change

Societies’ attempts to adopt patterns, behaviors, or models that have been tried successfully elsewhere and are taken as models to be replicated in new settings or environments that differ from that in which the ideas were developed or tested are referred to in the literature as ‘diffusion.’ Initially, the study of diffusion focused on the economic realm in general and on technological achievements in particular. The research looked at patterns of the adoption of successful economic models and tried to understand the methods and approaches by which some successes are adopted and tailored to new societies, with the changes required by the specific context.2

Later, social scientists also tried to understand the patterns of transmission of social and political ideas and models to societies that are unlike those in which they were developed and were first applied.3 The literature examines such transfers and adoption of ideas and models from various points of view. Some are based on attempts by stronger countries, in both the global and regional contexts, to offer disadvantaged states and societies models they can adopt. There are two types of models for these attempts. The first involves a ‘successful’ state that employs its political, military, and cultural might to get other societies to adopt its practices.4 One example is the Soviet Union’s campaign after the Second World War to force Eastern European and neighboring Asian countries to adopt Communist regimes. Another example is the attempt by the United States to plant liberal democracy throughout the world, which culminated in the 2003 invasion of Iraq that was conducted in order to install a democratic government in that country, or efforts to impose processes of democratization as a means to set up liberal democracies in the Arab monarchies after the wave of terrorism that struck the United States at the start of the twenty-first century.

Diffusion entails a reasonable level of desire on the part of the adopting/receiving society/state; in other words, the diffusion of ideas, models, and development plans requires a certain amount of ‘free will’ on the part of the receiving country or society

In tandem with these studies of diffusion, scholars proposed ‘soft power’ as a way to further the spread of successful models from one country to another. For example, Joseph Nye5 suggested that the West in general and more specifically the United States should ‘market’ their successful models by emphasizing their global dominance and success as being a result of the economic, social, and educational models they have implemented.6 In many ways, the Soviet Union after the Second World War, positioned itself as an alternative model to capitalism that third-world countries could adopt. Iran, too, proffered its Islamic Revolution as an idea and model to be copied elsewhere in the Muslim world, in light of what is presented as the successes of the Islamic Revolution that began in 1979.

Scholars of diffusion noted the dissemination of ideas or models from successful cases to other places. According to Jan Teorell,7 “diffusion may occur through imposition or emulation.” In the first case, countries that move towards democracy themselves try to promote democratization among their neighbors. In the case of emulation, by contrast, the driving force of diffusion comes from within the neighboring countries themselves. Countries follow the successful example of the neighbor that first installs democracy, by discovering “that it can be done” and learning “how it can be done.”

Kurt Weyland8 asserts that analysis of the factors behind diffusion reveals diverse components, which can be sorted into two categories. First, innovations can be transmitted by autonomous entities; alternatively, stronger entities can propose innovation and force them on weaker entities. He suggested four ways in which diffusion works. First, it may involve outside pressure by a stronger or dominant entity on a weaker state. This pressure can take the form of actual or threatened military intervention, economic pressure, or activating supporters inside the target country. Second –and this is the more standard way of promoting ideas– groups in the target country point to achievements by more successful countries and societies and thereby exert ‘soft’ and moral pressure for the adoption of ideas that have proven successful in other contexts. In other words, successful countries that have tried out various models use their soft power to market their models and ideas. Third, the weaker state/society can study models that might be appropriate for it. This study is carried out mainly by the leadership and elites who then propose that their own societies adopt these successful models, and the fourth mode of diffusion is a psychological response to failure or want. Societies that believe they have failed are apt to take over the experience of other countries or societies without studying them deeply. In such a case, the proposal to adopt another society’s model is selective and insufficiently grounded.

In many cases, the literature on diffusion confuses diffusion with other methods of borrowing norms or models. Vertical patterns for the transfer of ideas and models from more successful countries and societies to less successful ones by means of ‘hard’ (i.e., economic or military) or ‘soft’ power are not really diffusion. Diffusion entails a reasonable level of desire on the part of the adopting/receiving society/state; in other words, the diffusion of ideas, models, and development plans requires a certain amount of ‘free will’ on the part of the receiving country or society.

We argue that there are four prerequisites for diffusion to occur. First, there must be an asymmetry between the two societies or countries –the source of the ideas or models and the receiver/adopter. Second, the models or ideas must have a broad impact on the country or society where they are implemented. Third, the receiving country or society must go through a process of learning, comprehensive or selective, and then seek to adopt the models or ideas it views as successful and suitable to its own circumstances. In other words, the receiving country/society must have a strong desire to take this step. Fourth, large sectors of the population of the receiving country, both among the elites and the public at large, must support the adoption of these ideas; that is, this support is not restricted to the ruler or authorities. In other words, there is a widespread sense of something missing and a desire to adopt others’ models, along with public and political legitimacy to borrow these ideas.

The idea of learning from the experience of the West, while trying to adopt some of the models and plans implemented there, plays a key role in the life of Arab societies as well as in everyday discussions and arguments in the Arab world

Turkey and Iran: Models for the Arab World

The ideas and models proposed for adoption by much of the Arab world have diverse sources that go back a long time. Ever since the attempt by Muhammad Ali in Egypt (ruled 1805-1848) to adopt development plans from Europe, particularly France, there has been a continuing process of borrowing ideas that were spawned outside the Arab world (or at least proposals to do so). These include the concept of nationalism (both ethnic and territorial), modern forms of political organization, and even the nature of the regimes that ruled the Arab world after independence. These and other ideas are European notions that found key promoters in the Arab world. The idea of learning from the experience of the West, while trying to adopt some of the models and plans implemented there, plays a key role in the life of Arab societies as well as in everyday discussions and arguments in the Arab world.

During the two decades prior to the eruption of the Arab Spring, and in light of the rise of Turkey and Iran as regional powers, some in the Arab world had come to see these countries –along with the models they have tried and the programs they have carried out– as models to be emulated. As we will see below, there is substantial evidence in the Arab world of a comprehensive study of the economic, social, political, and military successes of Turkey and Iran. There is also Western (and not only Arab) encouragement to adopt the Turkish model, especially when it comes to the Development Party’s (Turkish: Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi or the AK Party) approach of integrating religion with democracy.9

This learning project seems natural and even obvious, given the characteristics shared by these two countries and much of the Arab world. Generally speaking, one can argue that there is a single geographical space that stretches from Iran in the east to Morocco in the west, with similar climatic and topographic features, a similar dominant culture and religion, a common history, and even a similar experience fighting colonialism.10 But in contrast to the Arab world, which has failed on many levels, Turkey and Iran are outstanding success stories, relatively speaking. Indeed, with the exception of the Gulf States that have been blessed with abundant oil reserves, it is hard to identify any successes in the Arab world, in any domain. Below we will describe the main efforts by Arab intellectuals and public figures to get the Arab world to adopt some of the models, plans, and ideas developed in Iran and Turkey in recent decades.

Based on that, the research examines the perception of Iran and Turkey among Arab leaders and intellectuals during the decade between 2002 and 2012. In the research we review reports, articles and interviews that discussed the Iranian and Turkish role as a model for the Arab region in that period, and examine public opinion about the two countries. In the latter case the research focuses on people’s classification and perception of the two states rather than facts about the two states; for instance, we do not examine the level of democracy in Turkey according to international reports, rather the perception of Arab societies about democracy in Turkey.

Turkey as a Source of Ideas and Models

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, or “Mister One Minute,” is a talent personality endowed with charm and an especially impressive power to engage people. Thanks to his charm, many Arabs view him as a model to be emulated. Erdoğan’s decisive influence over the Arab and Muslim societies in the region defies description and explanation. Did the Arab elites –whether nationalist, liberal, or Islamist– contribute to the creation of the image of this leader, or is the current picture the result of the Arabs’ weakness and sense of humiliation? In many ways, Erdoğan has evolved from a Turkish phenomenon to an “Arab/Islamic phenomenon.” This is how Iraqi writer Fadel al-Rubai11 begins his article on Turkey’s influence and attraction for the Arab world. He concludes that the admiration for Turkey resulted from the Arab world’s dire straits and backwardness, as opposed to Turkish progress and power, which the Arab world so strongly desires.12

Turkish influence in the Arab world has increased during the past decade, following the rise of Erdoğan’s AK Party.13 The AK Party has won five parliamentary elections since 2002; since then its governments have carried out both economic and political reforms, bridging religion and a market economy.14 Erdoğan himself has said that Turkey and its ruling party can serve as a model for the Muslim world.15 Some Western leaders and scholars, too, view Turkey as an authentic and different model that could challenge the existing order in the Middle East.16 It is important to note that some scholars view Turkey as a model only in terms of ‘theory’ and ‘intent,’ however.17 Even the Egyptian scholar Hassan Nafaa18limited the Turkish model to a success story worthy of study, one that can inspire the Arab peoples at this important and critical time in their history –namely, the Arab Spring– but not necessarily as something that can be duplicated elsewhere. Other scholars, though, do suggest the possibility of copying and implementing the Turkish model in Arab countries, as we will discuss at length below.

Turkey, which is a Muslim state by religion, a neighbor to the Arab world by geography, and a regional power, has attracted the attention of the Arab world, especially during the past decade

The idea that the Turkish model is replicable strongly penetrated Arabic public discourse in the immediate aftermath of the eruption of the Arab Spring in 2011 when some researchers viewed Turkey as an inspiration for the movement.19 The talk of Turkey’s role increased among Western intellectuals who viewed that country –a democracy with a Muslim majority– as a model and ‘the template of our times.’20 The same discourse took place among Arab intellectuals and scholars, as we will see below. A majority in the Arab world, among both intellectuals and the masses –although it is of course impossible to talk about absolute agreement– viewed Turkey as a role model for their countries, particularly in two areas.

The first is the economic realm, where Turkey’s achievements have exceeded those of the Arab countries.21 In the decade before the Arab Spring, the AK Party turned Turkey’s economy around, as reflected in the sharp increase in the standard of living. For the sake of comparison, fifty years before the Arab Spring, the level of development in Egypt and Turkey was nearly identical; so were per capita income and population. But International Monetary Fund data for 2010 indicate the per capita income in Turkey to be $9,890, as compared to only $2,771 in Egypt. Thus a yawning gap has opened between the two countries; they continue to resemble each other only in the size of their populations. But it is only in the first decade of the twenty-first century that this gap has become painfully clear. This economic gap, combined with other factors, has led Egyptians to confront their dissatisfaction with the regime to the point of rising up against it.22

The second domain in which Turkey can serve as a template for the Arab world is the model of political Islam that guides the country, and its integration of democratic elements with a religious outlook in a fashion suitable to a popular culture that views religion as an important part of life. The AK Party was careful to promote moderate Islamic values through democratic decision-making processes; for example, the government did not ban the consumption of alcohol, but rather limited it by increasing taxes and regulating the sale of alcoholic beverages.23 At the same time, Turkey under the leadership of the AK Party strengthened democratic values within the political system, defying the stereotypical notion that an Islamist or Islam-influenced party would not abide by or bolster democracy. Within less than a year of taking office, the party passed two democratization packages that introduced long-sought changes related to freedom of expression, freedom of association, and civilian control of the military.24 Arab scholars saw that the Turkish experience was worthy of study, given its honest, open, and free elections, enactment of democratic reforms, and assertion of civilian control of the military.25

Turkey through the Eyes of the Arab Public

According to a survey of more than 2,300 persons conducted by the Turkish Economic and Social Studies Foundation in July 2009, the vast majority of the Arabs in several leading Middle East countries see Turkey as a successful model and as proof that Islam and democracy can coexist. The survey found that 61 percent of the respondents in Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, and Saudi Arabia viewed Turkey as a successful model of progress and development. For our present purposes, the survey’s most significant finding is that 66 percent of respondents agreed that ‘Turkey can be a model for Arab countries’ and a similar percentage view Turkey as ‘a successful example of the coherence between Islam and democracy.’ The fact that even in Saudi Arabia 55 percent of the respondents felt that Turkey could serve as a model demonstrates the strength of this belief. The Turkish experience of democracy is viewed as a success by people in all eight of the countries in which the study was conducted; Turkey is seen as representing a good synthesis of religion and democracy. The same survey demonstrates the importance that Arab respondents attach to economic issues; in fact, they rank economic issues as being of the greatest concern in their own countries, as contrasted with Turkey, which enjoys strong economic growth.26

There are various reasons for seeing the Turkish model as an attractive paradigm, one of which is Islamic identity. Some 15 percent of the respondents noted Turkey’s ‘Islamic identity’ as the main reason they were impressed by the Turkish model; others mentioned the country’s democratic government, economy, and defense of Palestinian and Muslim rights as reasons to view the Turkish model favorably.27 71 percent of the respondents to the Turkish institute’s survey believed that Turkey’s influence in the region had increased in recent years. The survey also suggested that Turkey heads the list of preferred tourist destinations. Turkish influence was further apparent in the fact that 78 percent of respondents had seen at least one Turkish film. All of these factors indicate that Turkey enjoys strong influence in the region.28

The Turkish economic model is better suited to the Arab world than models from other countries, because Turkey is closer to the Arab world than the West

It is also possible to assess Turkey’s influence in the Arab world from the responses to a question asked of a representative sample of respondents in five Arab countries by a University of Maryland study in 2010. The question, which was part of a larger survey, reflected Turkey’s importance for Arabs. The survey asked, ‘Looking at the international reaction to the events in the Arab world in the past few months, which two countries do you believe played the most constructive role?’ Turkey received fully 50 percent of the vote, followed by a long list of other world powers.29 This demonstrates the Arab world’s sense of Turkish influence, a result of Turkey’s status and the positive view of the country. In the same survey, Turkey’s then Prime Minister Erdoğan was the most admired world leader, with 22 percent of the support, far outstripping the runners-up, who received only 13 percent and 14 percent, respectively.30

Turkey as a Model: Economic Achievements, Democracy and Religion-State Relations

Economic development, democracy, the status of political Islam, and the country’s growing military might have made Turkey a source of inspiration for Arabic speakers throughout the Middle East.31 Turkey, which is a Muslim state by religion, a neighbor to the Arab world by geography, and a regional power, has attracted the attention of the Arab world, especially during the past decade. Moreover, the peoples of the Middle East see it as a prime example worthy of emulation; this is not just the opinion of Erdoğan, who said that Turkey has become a model being emulated in various countries in the Muslim world,32 but also of other leaders, scholars, and politicians in Arab countries, especially Islamists.33

Rachid Ghannouchi, the leading Tunisian theologian, chairman of the Ennahda movement, and one of the most prominent ideologues of political Islam in the Arab world, observed, “Turkey is a true democratic model that can be emulated in order to establish a state that combines Islamic values with those of modern democracy.”34 Ghannouchi praised Turkey’s adoption of democratic values while showing respect for Islam as a step that could be duplicated in the Arab world, including Tunisia.35 He noted the importance of Turkey’s economic growth, which he saw as another brilliant element that must be incorporated into the Tunisian model and which could serve as a model for the entire Arab world. He added, “Turkey is not a model only for Tunisia but for all Arabs, because of the supreme importance it has attached to economic development, the war against corruption, an independent judiciary, and control of the military, and not ignoring the public’s desires and expectations. This has made Turkey a good example and model for the Tunisian and Arab peoples.”36

The main political reform in Turkey, which could serve as a model for Arab countries, is the amendment of the constitution and restriction of the military’s role in political life and in the state in genera

The Turkish economy and the governmental policy that spurred its growth have created a model that several scholars and politicians have proposed duplicating in Arab countries. UN reports and other studies about Arab states have noted to the sorry state of the free market and employment there, despite the increase in the number of those with higher education.37

In a Majallat al-Iqtisadiat interview, Abd-ElkhalekTohamy, a Moroccan economist, said explicitly that the Turkish economic model, which led to unprecedented growth, is brilliant and worthy of replication.38 By turning the country into the world’s fifteenth-largest economy in terms of GDP, the Turkish economic model excited the Arab world.39 The Turkish economic model is better suited to the Arab world than models from other countries, because Turkey is closer to the Arab world than the West; it is difficult to see how the latter could serve as a realistic model for the Arabs. The economic progress and growth sought by Arab countries exists in Turkey, which is closer to them in terms of geography, population, culture, economy, and shared history than the West is. All this suggests that the Arab countries should take Turkey as their economic model.40 Besides providing an economic model, Turkey has also played a significant role in the political sphere and become a political model as well, especially in terms of democracy and stability.41

The importance of the Turkish political model goes beyond the Arab public. In 2010 –before the Arab Spring– Syrian President Assad said that the Turkish model was important for the region. He also talked about the popular and political movement in the Arab world, and especially in Syria, towards rapprochement and stronger ties between the Turkish and Syrian peoples, who are close, in geographic terms and religious affiliation. All of this was possible, he said, because the regime enjoyed legitimacy, was committed to the people’s demands, and, by liberating the country from the international agenda, was free to act in accordance with the people’s wishes.42

The main political reform in Turkey, which could serve as a model for Arab countries, is the amendment of the constitution and restriction of the military’s role in political life and in the state in general. According to Fahmi Huwaidi, reining in the military can promote democracy and the state; that is exactly what Egypt can learn from the Turkish model.43 The comparison that scholars draw between Turkey and Egypt, for example, demonstrates Turkish superiority in a variety of fields and emphasizes the political model it offers. Bashir Abdel Fattah44 listed several laudable steps taken by the Turkish government under Erdoğan, such as the new Turkish constitution, which is seen as more democratic and respectful of the country’s political and cultural pluralism, as well as the reform of the Constitutional Court, so that it now resembles its counterparts in EU countries. With regard to the relations between the state and the military, he noted that “Erdoğan traveled a long road to limit the role of the Turkish military, [which he did thanks to] support from the West and some liberal elements, as well as some generals’ understanding of the Turkish condition.”45According to Abdel Fattah, the AK Party did not raise controversial issues such as identity, secularism, head coverings, and the status of the military at first. Instead, it began by notching economic achievements and growth, which generated the overwhelming public support that later helped it stare down its rivals and tackle more controversial issues. The Egyptian Freedom and Justice Party, by contrast, did not enjoy the same support.46 This comparison by an Egyptian scholar reflects the favorable attitude towards the Turkish model and the need for Arab countries to adopt it.

Abdel Fattah reaches the conclusion that the political sophistication and intellectual flexibility of the AK Party in Turkey far exceeds that of the Egyptian Freedom and Justice Party.47 The fact that this comparison was articulated by a liberal Egyptian intellectual reflects the value that the Arab world attaches to the Turkish model; Arab intellectuals juxtapose the Turkish model with Arab regimes and see it as one to be copied or at least learned from. This is because Turkey, as mentioned above, is close to the Arab sphere, both culturally and politically.48

An additional lesson from the Turkish elections and the Turkish model is the strong role that Turks accord to religious observance, belief, and identity, despite the history of the preceding decades

Other Arab politicians view Turkey as representing the enlightened side of Islam. That, at least, is the claim of Khaled Mashal, chairman of the Hamas Political Bureau, who added that Erdoğan is a leader not only in Turkey but throughout the Muslim world.49 The Arab world sees the AK Party as an Islamic party, despite its platform and insistence that it is secular. Indeed, it is impossible to ignore that the party’s leaders over the past decade have been affiliated with a strong Islamic tradition and are among the founders of political Islam in the country. This, in fact, is how the Turkish people view them. As a result, Arabs –and especially Islamists– build on the Turkish experience; they want it to succeed and are happy to see it prosper.50

An additional lesson from the Turkish elections and the Turkish model is the strong role that Turks accord to religious observance, belief, and identity, despite the history of the preceding decades. Given a democratic franchise, as in Turkey, the Arabs too would elect parties that espouse political Islam. Thus, Turkey embodies the desires of the Arabs who cannot exercise this right in their own countries because of the nature of the regime.51

Iraqi scholar Rabia al-Hafez emphasizes that the Arab public’s way of thinking has changed in recent years. After a decade of political catastrophes, they have begun thinking outside their immediate geographical surroundings and are trying to learn from others’ successes in order to overcome their own domestic crises. They prefer a model of a country whose values suit them and enjoy their support. Al-Hafez cites Turkey as an example and suggests that its aptness as a model derives from the fact that the Turkish political system combines Islamic integrity with an effective administration, with no attention to race or ethnic origin. In this way, the state becomes an umbrella that covers the entire community. This is the situation that the Arabs seek but do not currently enjoy, because of the political environment that has no mechanisms for reform.52

On the other hand, when it comes to the status of religion in the country, various groups view the Turkish model in different ways, yet nevertheless, all admire Turkey. Islamists see the AK Party as an Islamic party whose leaders will continue to hush this up until they have totally eliminated the military and the militant secularists –at which point the party will publicly declare its embrace of Islam. Another group that supports the Turkish model is formerly affiliated with Islamist movements who later decided that they could not support the slogans of a sharia state. They have been trying to confront a new reality that supports the limited expression of religion –so that the state is run without bringing religion into every matter. The third group is Arab secularists who take the Turkish model as an example they can hold up to Islamic movements of a secular Muslim state in which political parties with an Islamic background take part in elections but do not implement Islam in the political arena.53

In conclusion, over the past decade, the Arab world has come to take Turkey as a model. Syrian journalist Faisal al-Kasim believes that this model is a good one, concluding: “In short, Erdoğan’s party is the perfect one for Arabs to join on the ethnic, economic, and democratic levels.”54

From Inspiration to Attempts at Implementation

During the first stage of the Arab Spring, in which old regimes were toppled and replaced with new ones in Tunisia, Egypt and Libya (2010-2012), several attempts were made to borrow from the Turkish example. Some countries were better set up than others to learn from or implement the model of a flourishing country like Turkey.55 It makes good sense for Islamic parties that have acceded to power in other democratic countries to try to copy the Turkish model.56 Reformists in the Middle East, too, can point to and emulate Turkey as a model for democracy.57

Moncef Marzouki, the left wing nationalist who became president of Tunisia after the Arab Spring, said during a visit to Turkey that his country wanted to learn from and enjoy the Turkish experience, and had the wherewithal to do so. He added that he hoped Turkey would not be stingy in providing his country with its expertise and experience.58 Similar sentiments were voiced by Rachid Ghannouchi, the chairman of the Ennahda Islamic party in Tunisia, who promised that his party would emulate the AK Party when it took power.59 Study of and inspiration by the Turkish model was not limited to speeches; it was expressed in several agreements –especially on economic issues– between the Turkish and Tunisian governments, as well as in visits to Tunisia by Turkish business people. In addition to emulating Turkey on the economic front, the Tunisians also wanted to learn from the Turkish model of democratic government.60 The Turkish health care system won plaudits, too; the Tunisian Minister of Health emphasized the value of studying the Turkish experience in that field. He referred to Turkey as a successful experiment and proposed that the two countries launch mechanisms for collaboration in areas such as health insurance, organ transplants, cardiac surgery, pharmaceuticals, and health care infrastructure. He also noted the existence of health care agreements between the two countries.61

In Egypt, the study of the Turkish model began only a few months after the revolution; the Freedom and Justice Party (the political arm of the Muslim Brotherhood) consulted with Turkish investors in Cairo, who also served as advisors to the Egyptian government, in order to learn and benefit from Turkish experience in waste recycling and energy, street sanitation, and traffic management.62

After the presidential elections and the Freedom and Justice Party’s victory in the Egyptian parliamentary elections, the party, which had been tapped to form the new government, sent Deputy General Guide Khairat el-Shater to Turkey at the head of a team to learn details of the system set up by the AK Party, especially in terms of economic issues. The team was to learn from the Turkish experience before the Egyptian party formed its first government. The trip was meant to be only the first leg of a continuing tour to learn from countries with successful governments.63

Former Egyptian president Morsi himself visited Turkey in order to study the Turkish Islamists’ model and experience and take home economic lessons. Egyptian businessman Hassan Malek, a Brotherhood member who accompanied Morsi, said that Egypt could learn a great deal from Turkey with regard to commerce and industry –especially clothing manufacture and electronics.64

Other ministers and members of parliament, too, visited Turkey to study the Turkish model. The Egyptian Minister of Infrastructure met with the mayor of İstanbul to discuss water and sewage treatment.65 The Shura Council –the now-abolished second chamber of the Egyptian parliament– sent a delegation to Turkey to study options for developing local government and the decentralization of power. The Egyptian committee indeed presented a proposal, based on its findings, to enshrine the role of local government in the new Egyptian constitution.66 Finally, we must note that it was not only Islamic movements that were inspired by the Turkish model; so were other political streams and many of the young people behind the revolution.67

In conclusion, it is clear that besides its echoes in the discourse on three basic domains –economic achievements, political reforms, and religion-state relations– the emulation of the Turkish model passed to the implementation stage in a number of countries and societies.

Although we cannot overlook the fact that some segments of Arab society view Iran as an enemy, the country has several features that have made it a paradigm for others

Iran as a Model for Emulation in the Arab World

Iran is another Middle Eastern country that has served as a model and inspiration for many in the Arab world. Several factors have turned Iran into a regional power and role model. Although we cannot overlook the fact that some segments of Arab society view Iran as an enemy, the country has several features that have made it a paradigm for others. “Iran is a model we should emulate,” said the Lebanese foreign minister at the Non-Aligned Summit in 2012, and added that Iran is a living example of a country that is developing on all fronts and enjoys full independence.68 This view of Iran stems from the fact that Iran and the Arab world see themselves in the same boat and facing a common enemy.69 This ‘boat’ exists, according to Jordanian writer Thaher Amr,70 because the commonalities between the Iranians and Arabs are far greater than what divides them. They share an Islamic culture and civilization and confront the ‘Zionist enemy’; the differences between Arabs and Iranians are less important than what separates both of them from Israel.

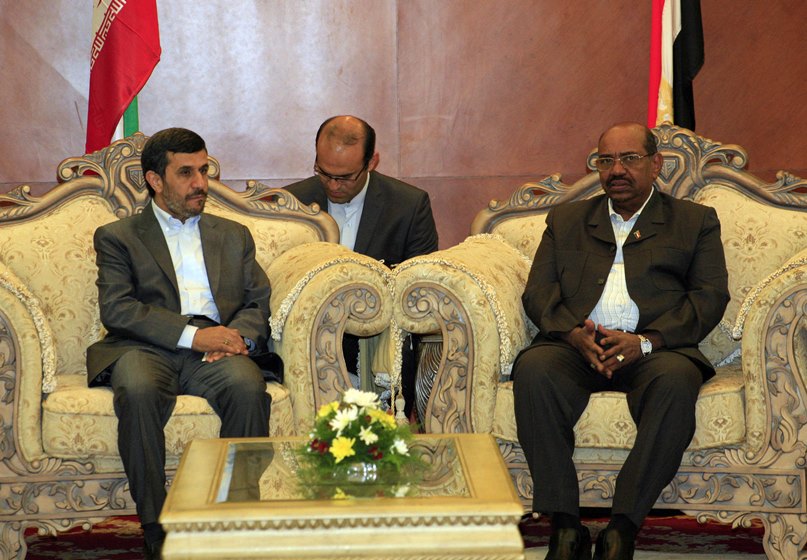

In another part of the Arab world, the speaker of the Sudanese National Assembly, Ahmed Ibrahim al-Tahir, said that his country takes Iran as its Islamic model. Sudan, in turn, suggests that other countries in the region take Iran as a model. Al-Tahir went on to say that the countries that experienced the ‘Islamic Spring’ (by which he meant the Arab Spring) should learn from the Islamic Republic of Iran.71 He was also excited by the strength and solidarity of the Iranian leadership, which prevented political chaos and an international embargo on Iran.72

The Iranian model analyzed here is primarily that of Khomeini’s 1979 Islamic Revolution. From the outset, this model fascinated the Arab world, especially the Islamists, including the Islamic Jihad and other Sunni movements like the Muslim Brotherhood, who were stimulated by the slogans of the Islamic Revolution in Iran.73 In fact, the model of political Islam represented by Iran and the Khomeini revolution was what stirred all of the Islamic movements into life.74

The Iranian model manifested in the Islamic Revolution led Arab Islamists to hope that it could serve as a useful and general Islamic model that could withstand the hegemonic Western model.75 Some Islamists were attracted to the Iranian Revolution, primarily in its early years, in order to learn from it as a realistic and optimum model, inasmuch as post-revolution Iran was the only true Muslim country.76 Leaders of the international Islamic movement like Hassan al-Turabi saw the Iranian model as worth learning from.77 Rachid Ghannouchi went so far as to say that the Iranian Revolution was “the greatest earthquake that shook the Islamic world in the twentieth century...”78

Sudanese politicians, who consider Iran as an Islamic model, often exchange views with Iranian leaders. | AA Photo / XINHUA

Arab Public Opinion about Iran

The data from the 2010 survey that was conducted at Maryland University among 3,000 citizens in several Arab countries (Egypt, UAE, Morocco, Lebanon, and Jordan) showed that they supported the Iranian position that the country has a right to develop a nuclear program. The 64 percent support and 25 percent opposition shows that most Arabs view Iran’s nuclear program positively, even though 52 percent assume that it is military in nature and only 33 percent believe the Iranian claim that it is meant solely for peaceful purposes. The Arabs’ view of Iran as positive (or at least non-threatening) is evident from the same survey. When respondents were asked which two countries posed the greatest threat to them, only 18 percent chose Iran, and 71 percent Israel. The same survey revealed admiration for former Iranian Prime Minister Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who came second after Erdoğan as the most-admired leader in the region. The fact that Ahmadinejad was cited by 13 percent of the respondents (22 percent named Erdoğan) reflects the positive opinion of the Iranian leadership.79

Elements and Traits Admired in Iran: Technological Achievements, Military Power and Leadership

There are a number of reasons why Iran became an inspiration for the Arab world in the period before the eruption of the Arab Spring: its assertion of Islamic might, military power, and technological progress, its opposition to Israel, and its dedicated and responsible leadership. As we will see below, these qualities are what Arabs and Muslims want from their leaders and what Iran has managed to accomplish, in stark contrast to the Arab states’ failures.80

It is important to note that not all of the Arab world takes Iran as a model, given that many Arabs do not see eye-to-eye with Iran on various issues. Nonetheless, Iran has some qualities that make it an appealing model and inspiration, given the Arab states’ weakness, which has permitted Iran to achieve a dominant position in the region.81 But not only the Arabs’ failure led to the positive view of Iran; according to Kassem,82 Iran wins respect for its success on several fronts. It is impossible to indict Iran for its national project; instead, the Iranian method should be admired and studied, especially in the military domain and the development of a military and nuclear infrastructure that has attracted the attention of the entire world. This is in addition to the regular civilian industry that has been built up by the Iranians themselves, the end result being a strong and independent country, in contrast to the Arab states. Kassem adds that the Arabs need to employ the same strategies, based on power and planning. They also need to emulate the Iranian’s laudable patience and persistence in construction and planning.83

Some Arabs see post-1979 Iran as the Arabs’ greatest ally against the increasing foreign threats in the region –first and foremost the threat posed by Israel, which is supported by the United States and by the West in general. Some Arabs believe that the Islamic Republic of Iran is a gift sent by Allah to stand by them in their historic crisis, a crisis manifested in the pressure that Israel and the United States exert on them, as well as in the Arabs’ misery under leaders who have retreated from their nationalist policies. Iran today is perceived as the major military power that can be depended on in future conflicts with Israel and American and Western policies in the region. Many Arabs view Iran as continuing in the path of the Arab nationalists who resisted the colonial project.84

Iran, especially because it encourages and supports Arab groups and movements and supplies them with arms, is viewed as a model for the struggle against colonialism and occupation, and has accordingly become a source of inspiration for the Arab resistance

Thus Iran, especially because it encourages and supports Arab groups and movements and supplies them with arms, is viewed as a model for the struggle against colonialism and occupation, and has accordingly become a source of inspiration for the Arab resistance.85 Many do not see it as meddling in the internal affairs of Arab states or infringing on their sovereignty, but as strengthening the resistance and serving Arab interests.86 Khaled Mashal, the head of the Hamas political bureau, has said that Iran provides a model for all the peoples of the world in its resistance and overcoming of challenges. He approvingly noted Iran’s support for the Palestinians and its resistance to the West.87

According to the liberal Syrian intellectual Burhan Ghalioun, the Syrian regime, which has had a strategic alliance with Iran for more than 30 years, sees that country in a positive light. So do some opposition groups of the political elite, Islamists, the nationalist left, and large swaths of public opinion.88 Iran’s military might and fierce hostility towards Israel amplify its favorable image as a leader in the resistance to Israel and supporter of the Palestinians, in lieu of the militarily inferior Arab states.89

Iran’s military and technological successes inspire other countries. It has developed long-range missiles, enriched uranium to 20 percent, and operated the Bushehr nuclear reactor –all things that the Arabs have not done and for which Iran should be esteemed.90 According to a former senior inspector for the International Atomic Energy Agency, Yusri Abu Shadi, Iran’s construction of a thousand-megawatt nuclear reactor –nothing comparable exists in any Arab country– highlights its technological prowess and is the type of project that Arab countries should emulate –especially because they need to find alternative sources of energy, as Iran has done.91 Iran knows that it cannot have a strong economy if it fails to ensure energy diversity; as such, it can be considered a model for strategic planning in domestic and foreign affairs, as well as crisis management and response.92 Iran’s technological and industrial successes go beyond the military to other areas where it can inspire other countries.

Three energy companies from Russia, Turkey, and Iran, the latter two considered as examples from most Arab states, signed a contract worth $7 billion in 2017. | AA Photo

In addition to its own military might and technological advances, Iran arms the Palestinian resistance organizations, which consequently feel that, in the words of Hamas leader Mahmoud al-Zahar, the Arab countries should copy Iran’s example of aiding the Palestinian resistance.93 Iran has also supported the Lebanese resistance (i.e., Hezbollah), which has fought against Israel for more than three decades and won popular support in the process. Israel’s withdrawal from southern Lebanon in 2000 is considered to be a great victory for Hezbollah, the Arabs, and Iran, the organization’s chief sponsor. Lebanese writer Marwah Abu Muhammad entitled her article to mark the anniversary of the Israeli withdrawal ‘Iran Won!’ and evaluated the Iranian role in Israel’s expulsion from southern Lebanon.94

The Iranian leadership, which has propelled the Islamic Republic forward, also engendered great excitement among some in the Arab world. As a former leader of the Muslim Brotherhood, Kamal Helbawy, told an interviewer, “I am strongly impressed by the Iranian leadership, especially Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and President Ahmadinejad, because I have not found any Arab ‘leader’ anywhere in the world with their integrity. They are heroes, courageous and honest, devoted to the Palestinian cause and helping others while aiding guerrilla movements. It is enough that they want to free the occupied land from the Zionist entity; it suffices to say that during the revolution they gave the Zionist embassy to the Palestinians after they expelled the ambassador. This could happen in Egypt; we’re praying.”95

Iraqi writer Omar Dhahir supports this notion, saying that Iran, as the only Islamic and Shiite state, enjoys emotional and ideological support that other Arab countries do not. This support comes primarily from Shiite Muslims but also from millions of other Muslims who respect Iran’s independence and its leaders’ dedication. Muslims and Arabs also esteem Iran’s sincere opposition to Israel.96

In conclusion, we see that in the case of Iran, which was primarily a source of inspiration in the military field, technology and resilience, there has been less of a tendency for its influence on the Arabs to transition from ideology to implementation

Iran is perceived as combining Islam and social values with democracy and free elections, and as a nation that is aware of its surroundings.97 Finally, the Iranian leadership itself views the Iranian republic as the model of democracy that should be copied by other countries in the region; according to Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif, it is the local model that the rest of the region should learn from.98

From Inspiration to Implementation

The Iranian model has spawned serious study and attempts at implementation by some Arabs –but to a lesser extent than the Turkish model. The latter is more accepted and tends to be viewed more positively –especially after the first stage of the Arab Spring (2010-2012)– as a result of the negative perception of recent Iranian positions and because of the sectarian divide.99 But there are some who take the Iranian model as worthy of emulation and continue to try to learn from it. As noted above, the Iranian model was especially successful with regard to the country’s military might and nuclear program. The Arab world will not emulate this last element of the Iranian model –at least not openly– because of the sensitivity of this issue for the international community. No countries are currently learning from or copying Iran on the nuclear front –at least not in public view.

However, former Egyptian president Mohamed Morsi declared that his country would use nuclear energy to generate electricity.100 Egyptian scholars have suggested that Morsi wanted to copy the Iranian model and that the Iranians offered to help him develop a nuclear program.101 It is important to note, though, that Israel took a very dim view of Morsi’s declaration, seeing it the same way it sees Iran’s nuclear program.102

In the other hand statements by Hisham Bastawisy, the former vice-president of the Egyptian Court of Cassation, indicate that Morsi was planning to study and implement the Iranian model of religion-state relations and institute an electoral democracy along the lines of the Iranian model –meaning that only Islamic parties would be allowed to run. Some, though, believe that Morsi was opposed to the Iranian plans for the region and wanted to increase Sunni power and head the Sunni bloc.103

These successes are attractive because Iran and Turkey are Islamic and Middle Eastern countries and thus very close to the social realities of the Arab world

Iran’s conduct of its negotiations with the West and to some extent the leadership’s intransigence are also taken as a model for emulation in the Arab world. For example, Mohsen Abu Ramadan believes that the Palestinians must learn how to negotiate and record victories in their struggle with the Israelis; namely, they need to achieve superiority and the influence and power that will give them a negotiating edge –just as the Iranians did in their negotiations with the West.104

Iran is viewed favorably in the domains of energy, transportation, and even hygiene –the very areas in which Egypt and other Arab countries have much to learn.105 Thus, the Iranian model has also gained hold in industry and agriculture; for example, Sudan tried to copy Iran’s lead in meat production. To that end, Iran and Sudan are working together; the Sudanese Agriculture Ministry and Iranian entrepreneurs are collaborating to improve the Sudanese market and learn from Iranian experience in agriculture and animal husbandry.106 The collaboration between the two countries extends to other realms as well. Several economic agreements have been signed, and Iran has indicated its willingness to help Sudan with problems such as desertification. There have also been several military cooperation pacts which allow Sudan to benefit from Iranian military advances, especially missiles. All of this reflects a positive view of the Iranian model and a desire to implement it.107

Although the Gulf States’ relations with Iran remain tense, some have tried to learn from its experience. Thus, the Omani Minister of Heritage and Culture noted the importance of the Iranian model and experience in preserving heritage and culture. The two countries signed an agreement for Oman to send experts to Iran to study research methods and techniques for preserving and documenting national heritage sites and antiquities.108

Iran has been subjected to several rounds of sanctions imposed by the rest of the world because of its nuclear program, and has learned to live with these restrictions (mostly economic). Here too it can serve as a model. For example, Russia submitted an official request to learn from Iran’s experience in dealing with sanctions, in the wake of the sanctions that targeted Russian leaders.109 In the same vein of economic management during a crisis, an Egyptian expert studied the Iranian model of financial support to the different social classes. This is what Iran has managed to do, and, according to the expert, what Egypt must do as well.110

In conclusion, we see that in the case of Iran, which was primarily a source of inspiration in the military field, technology and resilience, there has been less of a tendency for its influence on the Arabs to transition from ideology to implementation. This is largely because of the difficulty in implementing the Iranian nuclear program and the international community’s unwillingness to allow other countries to go nuclear. But there are other fields in which Iran is a source of inspiration; in those areas, various countries and groups in the Arab world have proposed implementing the Iranian model, as noted above.

Discussion and Conclusion

The willingness of some elements in the Arab world to adopt ideas that have been successfully implemented in various societies in Europe is not a new phenomenon. The initiatives for these emulation projects came from leaders who wanted to make their societies more western; these included Muhammad Ali and his descendants in Egypt and the Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II, as well as social activists and intellectuals who launched processes based on their personal experiences in the West or their study of the West’s successes from afar.

In recent years, we have seen both the public and elites calling for Arab society to learn from the West and adopt some of its achievements to improve their situation. But we have also witnessed a clear trend of public advocacy to emulate the successful models of non-Arab Muslim countries. Turkey and Iran stand out as the most important magnets in this regard. During the past two decades, the Arab world has conducted a wide-ranging discussion of Turkey’s and Iran’s achievements and has recognized a need to learn from their experience and copy their successes. These successes are attractive because Iran and Turkey are Islamic and Middle Eastern countries and thus very close to the social realities of the Arab world.

In addition, the relationship between Turkey and Iran, on the one hand, and the Arab world, on the other, exemplifies the four prerequisites for diffusion to take place. First, there is an asymmetry between Iran and Turkey, and the Arab world. The two countries’ achievements are impressive on an objective scale –and even more so when compared to the Arab world, where the achievements are more modest and failure has been more common than success. Second, the models or ideas that many Arabs believe should be copied from Turkey or Iran have a broad and comprehensive effect on their societies. A close look at the economic, social, and structural successes in Turkey and Iran shows that they encompass the totality of each society. Third, the call in the Arab world to adopt parts of the successful Turkish and Iranian models is based on a study of these successes and the conviction that the situations in Turkey and Iran, on the one hand, and the Arab world, on the other, are analogous, so that it would certainly be possible for the latter to emulate or adopt the Iranian and Turkish experience in specific areas. Fourth, there is broad support in large sections of the Arab world –both among the masses and the elites– for adopting the successful models from Turkey and Iran. In other words, the idea of learning from these two success stories enjoys the broad public support and is not just the pet project of regimes and rulers.

During the years before the eruption of the Arab Spring, especially following the rise to power by Erdoğan in 2002, and the intensification of western pressure against Iran under the shadow of its nuclear project, many Arabs among the public as well as the elites expressed a high level of admiration for the Turkish and Iranian experience and these countries’ successes in different domains. This growing admiration was accompanied by a clear call by Arab elites and activists to emulate and adapt different aspects of achievements by Turkey and Iran into the Arab world.

Our main theoretical and analytical lessons in this article are reflected in the following points:

First, emulation of and the learning process from successful cases is not limited to leaders, elites and activists. In the age of mass communication and social media, it is also related to the public’s awareness of the gaps between them and surrounding successful cases. Second, the accelerated level of diffusion is a major source of unrest in weak societies, i.e. diffusion and demands for emulation help explain the unrest and revolutionary mood among the Arab public during the Arab Spring. Third, diffusion, by nature, is related to the willingness of the weak and less successful to learn from the strong and successful; still, the learning process is a selective one, and related to perceptions of success, something that was clear as part of our analysis. Turkey and Iran are sources of a learning process and emulation in different aspects of life, rather than comprehensive models on all fronts. Fourth, diffusion is not a process of learning from the west only; regional powers, Iran and Turkey in our case, are a major source of diffusion and emulation in the Arab world.

The failed regime-change process in parts of the Arab world and the slowdown in the wave known as the Arab Spring has led to a decrease in motivation and in the discussion of the need for the Arabs to copy Turkey and Iran

The call to emulate aspects of success from Turkey and Iran enhanced the level of unrest in the Arab world and cultivated the ground for public protest in several Arab societies during the Arab Spring, and was part of the public agenda of the newly elected regimes in Tunisia and Egypt during the first phase of the Arab Spring, i.e. until the military coup against Mohamed Morsi in July 2013.

Recently, the failed regime-change process in parts of the Arab world and the slowdown in the wave known as the Arab Spring has led to a decrease in motivation and in the discussion of the need for the Arabs to copy Turkey and Iran. Nonetheless, there is still broad support for this idea. A new surge in its favor could constitute a major element of the public discourse in the Arab world if the countries’ stability permits it in the future.

Endnotes

1. Trita Parsi and Reza Marashi, “Arab Spring Seen from Tehran,” The Cairo Review of Global Affairs, Vol. 2, (2011), pp. 98-112.

2. Marie-Laure Djelic, Exporting the American Model, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), pp 1-322; Marie-Laure Djelic, “Social Networks and Country-to-Country Transfer: Dense and Weak Ties in the Diffusion of Knowledge,” Socio-Economic Review, Vol. 2, (2004), pp. 341-370; Walter W. Powell and Paul J. DiMaggio (eds.), The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), pp. 1-486.

3. David Strang and John W. Meyer, “Institutional Conditions for Diffusion,” Theory and Society, Vol. 22, No. 4 (1993), pp. 487-511; Pamela S. Tolbert and Lynne G. Zucker, “Institutional Sources of Change in the Formal Structure of Organizations: The Diffusion of Civil Service Reform, 1880-1935,” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 28, (1983), pp. 22-39.

4. Jan Teorell, Determinants of Democratization: Explaining Regime Change in the World 1972-2006, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), pp.1-222; Kurt Weyland, “The Diffusion of Revolution: ‘1848’ in Europe and Latin America,” International Organization, Vol. 63, No. 3 (2009), pp. 391-423.

5. Joseph S. Nye, “Soft Power,” Foreign Policy, Vol. 80, (1990), pp. 153-171.

6. Marie-Laure Djelic, “Social Networks and Country-to-Country Transfer: Dense and Weak Ties in the Diffusion of Knowledge,” Socio-Economic Review, Vol. 2, (2004), pp. 341-370.

7. Teorell, Determinants of Democratization, p. 86.

8. Kurt Weyland, “The Diffusion of Revolution: ‘1848’ in Europe and Latin America.”

9. Gamze Çavdar, “Islamist New Thinking in Turkey: A Model for Political Learning?,” Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 121, No. 3 (2006), pp. 477-497

10. Meliha Benli Altunışık, “The Turkish Model and Democratization in the Middle East,” Arab Studies Quarterly, Vol. 27, No.1-2 (2005), pp. 45-63.

11. Fadel al-Rubai, “The Hidden Turkish Charm,” Al Jazeera, (June 9, 2010), retrieved August 24, 2014,

from http://www.aljazeera.net/

12. Juris Pupcenoks, “Democratic Islamization in Pakistan and Turkey: Lessons for the Post-Arab Spring Muslim World,” The Middle East Journal, Vol. 66, No. 2 (2012), pp. 273-289.

13. Omar Kosh, “The Turkish Position on the Arab Revolutions,” Al Jazeera, (June 10, 2011), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.aljazeera.net/

14. Alper Y. Dede, “The Arab Uprisings: Debating the Turkish Model,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 13, No. 2 (2011), pp. 23-32.

15. “Erdoğan: The Ruling Party in Turkey Is a Model for the Islamic World,” BBC Arabic, (October 1, 2012), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.bbc.co.uk/arabic/

16. Graham. E. Fuller, “Turkey’s Strategic Model: Myths and Realities,” Washington Quarterly, Vol. 27, No. 3 (2004), pp. 51-64.

17. Altunışık, “The Turkish Model and Democratization in the Middle East,” pp. 45-63; Burcu K. Erdem, “Adjustment of the Secular Islamist Role Model (Turkey) to the ‘Arab Spring’: the Relationship between the Arab Uprisings and Turkey in the Turkish and World Press,” Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations, Vol. 23, No.4 (2012), pp. 435-452.

18. Hassan Nafaa, “The ‘Turkish Model’ in the Mirror of the Arab Spring,” in Nathalie Tocci et al., Turkey and the Arab Spring: Implications for Turkish Foreign Policy from a Transatlantic Perspective, (Washington, DC: The German Marshall Fund of the United States, 2011), pp. 37-44.

19. Saim Kayadibi and Mehmet Birekul, “Turkish Democracy: A Model for the Arab World,” Journal of Islam in Asia, Vol. 8, No. 3 (2012), pp. 255-273.

20. Robert Tait, “Egypt: Doubts Cast on Turkish Claims for Model Democracy,” The Guardian, (February 13, 2011), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.guardian.co.uk/

21. Asli Ü. Bâli, “A Turkish Model for the Arab Spring?,” Middle East Law and Governance Vol. 3, No. 1-2 (2011), pp. 24-42.

22. Zafer Şenocak, “Is Turkey Considered a Model for the Arab World? What Does Turkey Do Differently,” Afaq al-Demoqratiyya, (2012).

23. Şenocak, “Is Turkey Considered a Model for the Arab World? What does Turkey do Differently.”

24. Çavdar, “Islamist New Thinking in Turkey: a Model for Political Learning?.”

25. Idris Boano, “Hidden Equations in the Conflict between the Islamic and Secular Streams in Turkey,” Al-Mustaqbal al-Arabi, Vol. 299, (2004). pp. 75-81.

26. Mensur Akgün, Gökçe Perçinoğlu and Sabiha. S. Gündoğar, “The Perception of Turkey in the Middle East,” Foreign Policy Analysis Series, Vol. 10, (2009), pp. 1-37.

27. Moustafa al-Sawwaf, “Turkey: A Model for the Aspirations of the Peoples of the Middle East,” Shbakat Anbaa Almalomatya, (March 2, 2011), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://annabaa.org/nbanews/

28. al-Sawwaf, “Turkey: a Model for the Aspirations of the Peoples of the Middle East.”

29. Shibley Telhami, Annual Arab Public Opinion Survey, (Maryland: Anwar Sadat Chair for Peace and Development and University of Maryland, 2011).

30. Shibley Telhami, Annual Arab Public Opinion Survey.

31. Akgün, Perçinoğlu and Gündoğar, “The Perception of Turkey in the Middle East,” pp. 1-37; Çavdar Gamze, “Islamist New Thinking in Turkey: a Model for Political Learning?”; Kayadibi and Birekul, “Turkish Democracy: a Model for the Arab World,” pp. 255-273; Boano, “Hidden Equations in the Conflict between the Islamic and Secular Streams in Turkey,” pp. 75-81.

32. “Erdoğan: The Ruling Party in Turkey Is a Model for the Islamic World.”

33. Amani Zahran, “Moushira Khattab: Turkey Is an Ideal Model for the Economy and Women’s Rights,” Al-Wafd, (March 21, 2013), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.alwafd.org?tmpl=

component&print=1&page.

34. “Rached Ghannouchi: Turkey Is an Ideal Model for the New Tunisia,” Al-Moslim, (January 25, 2011), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://almoslim.net/node/

35. Dietrich Jung, After the Spring: Is Turkey a Model for Arab States?, (Odense : University of Southern Denmark Center for Contemporary Middle East Studies, 2011).

36. “Rached Ghannouchi: Turkey is an Ideal Model for the New Tunisia.”

37. Filipe R. Campante and Davin Chor, “Why Was the Arab World Poised for Revolution? Schooling, Economic Opportunities, and the Arab Spring,” The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 26, No. 2 (2012), pp. 167-187.

38. “Turkey: A Shining Economic Model Tempts Comparison,” Medi1Radio, (2013), retrieved April 26, 2015, from http://www.medi1.com/

39. Zahran, “Moushira Khattab: Turkey is an Ideal Model for the Economy and Women’s Rights.”

40. Lewis Hobeika, “Turkey: A Good Economic Model for the Arabs,” Al-Sharq, (January 9, 2013), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.al-sharq.com/news/

41. Zahran, “Moushira Khattab: Turkey Is an Ideal Model for the Economy and Women’s Rights.”

42. Al-Quah al-Thalitha, “Assad in an Interview on TRT: Turkey Is an Essential Model in the Region… and We Are Consulting about Iraq,” Al-Quah al-Thalitha, (October 7, 2010), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.thirdpower.org/

43. Fahmi Huwaidi, “Turkey Is Paying the Price on Our Behalf,” Alkhaleej, (June 22, 2010), retrieved

August 24, 2014, from http://www.alkhaleej.ae/

3a6d5a346978.

44. Bashir Abdel Fattah, “The Islamists in Power: Differences between Egypt and Turkey,” Al Jazeera,

(August 7, 2012), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.aljazeera.net/home/

70ec-47d5-b7c4-3aa56fb899e2/

45. Fattah, “The Islamists in Power –Differences between Egypt and Turkey.”

46. Fattah, “The Islamists in Power –Differences between Egypt and Turkey.”

47. Fattah, “The Islamists in Power –Differences between Egypt and Turkey.”

48. Hobeika, “Turkey: A Good Economic Model for the Arabs.”

49. ‘Erdoğan: The Ruling Party in Turkey is a Model for the Islamic World.”

50. Yasser al-Zaatara, “The Secular Islamic Argument over Erdoğan’s Experience,” Al Jazeera, (October

16, 2007), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.aljazeera.net/

51. Yasser al-Zaatara, “The Mistaken Comparison between the Islamic and Turkish Experiences,” Al-

Hayat (August 23, 2004), retrieved August 24, 2014, from, http://daharchives.alhayat.

archive/Hayat%20INT/2004/8/23.

52. Rabia al-Hafez, “Turkey: This Is the Arabs’ Stance and these Are the Reasons,” Al Jazeera, (March 24, 2014), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.aljazeera.net/

53. Yasser al-Zaatara, “On the Victory by the Turkish Secular Islamic Model,” Al Jazeera, (August 7, 2008), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.aljazeera.net/

54. Faisal al-Kasim, “Arabs, Learn from Erdoğan!,” Al-Quds al-Arabi, (April 4, 2014), retrieved August 24, 2014, from: http://www.alquds.co.uk/?p=

55. Mohammad Madi, “The Turkish Model: Between the Impossible Inspiration in Egypt and the Possible in Tunisia,” SwissInfo.ch, (March 17, 2013), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.swissinfo.ch/ara/

56. Pupcenoks, “Democratic Islamization in Pakistan and Turkey: Lessons for the Post-Arab Spring Muslim World,” Middle East Journal, Vol. 66, No. 2 (Spring 2012), pp. 273-289.

57. Ömer Taşpınar, “Turkey’s General Dilemma,” Foreign Affairs, (August 8, 2011), retrieved August 24, 2014 from, http://www.foreignaffairs.com/

58. “Marzouki: Tunisia is Bent on Benefiting from the Turkish Experience,” Al-Masry al-Youm (May 29, 2013), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.almasryalyoum.com/

59. Jung, After the Spring: Is Turkey a Model for Arab States?.

60. “Erdoğan’s Visit to Tunisia,” Al-Dostor, (February 16, 2014), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.dostor.org/213162.

61. “Tunisian Health Minister Emphasizes the Need to Benefit from the Turkish Experience,” Akhbar al-Aalam, (October 1, 2013), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.akhbaralaalam.net/

62. Ahmad Fathi, “Freedom and Justice Conducting Extensive Contacts with the Turks to Take Advantage of their Experience in Solving Traffic and Waste Problems,” Shorouk News, (December 22, 2011), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://elgornal.net/news/news.

63. “Brotherhood Delegation Visits Ankara to Benefit from the Islamic Turkish Government,” El-Fagr,

(July 2, 2012), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://new.elfagr.org/Detail.

nwsId=136633#.

64. Inji Magdy, “Associated Press: Morsi Turns to Turkey to Learn from Islamists Experience There,”

Al-Youm al-Sabi, (September 30, 2012), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.youm7.com/News.asp?

65. Alia Qasem, “Cairo in the Footsteps of the Turkish Experience,” Al-Sharq- al-Awsat, (November 12,

2012), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://archive.aawsat.com/

703999&issueno=12403#.

66. Gihad Abdelmonem, “The Shura Council: Learning from the Turkish Model of Local Government,” Al-Wafd, (November 19, 2012), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.alwafd.org//307287.

67. “The Egyptian ‘Brothers’: Will They Duplicate the Turkish Experience?,” Al-Madina, (April 8, 2011), retrieved August 24, 2014, from: http://www.al-madina.com/node/

68. “Lebanese Foreign Minister: Iran Is a Present-day Model of Independence and Overall Development,” Al-Alam, (August 28, 2012), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.alalam.ir/news/

69. Fahmi Huwaidi, “Iran and the Arabs Are in the Same Boat,” Radio Islam, (July 26, 2000), retrieved August 24, 2014, from: http://www.radioislam.org/

70. Thaher Amr, “No Substitute for Dialogue with Tehran,” Al-Sabeel, (March 17, 2015), retrieved August 24, 2014, from: http://www.assabeel.net/

71. “Sudan: Iran Is an Islamic Model to Be Duplicated,” Al-Alam, (January 22, 2013), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.alalam.ir/news/

72. “Sudan: Iran is an Islamic Model to be Duplicated,” Al-Alam.

73. Azmi Bishara (ed.), The Arabs and Iran: A Review of History and Politics, (Doha: Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies, 2012), pp. 5-26.

74. Aziza Tariq, “Shiites between their Creed and Political Islam: Iran as a Model,” Safhat Syria, (January 13, 2013), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://syria.alsafahat.net.

75. Olivier Roy, L’Echec de l’Islam Politique (Failure of Political Islam), (Paris: Le Seuil, 1992).

76. Haidr Ibrahim, The Collapse of the Cultural Project, (Khartoum: Sudanese Studies Center, 2004).

77. Alnor Hamed, “Sudan and Iran: A Journey of Rapprochement and the Current Arab Arena,” Siyasat Arabiya, Vol. 1 (March 2013), pp. 58-71.

78. Rashid Ghannouchi, The Troubled Maghreb-Iran Relations, (Doha: Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies, 2010), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.dohainstitute.org/

371b-45be-8902-2bf895ff56a3.

79. Telhami, Annual Arab Public Opinion Survey.

80. Abdel Sattar Qassem, “Iran Will Lead the Muslim World,” Al-Mawqef, (January 9, 2014), retrieved August 24, 2014, from: http://almawqef.com/spip.php?

81. Abdullah al-Shaiji, “Iran and the Arabs: Friendship or Rivalry?,” Al-Ittihad, (April 27, 2009), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.alittihad.ae/

82. Qassem, “Iran Will Lead the Muslim World.”

83. Qassem, “Iran Will Lead the Muslim World.”

84. Burhan Ghalioun, Towards a Strategic Vision for Iran-Arab Relations, (Doha: Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies, 2010), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.dohainstitute.org/

85. Graham. E. Fuller, “The Hizballah-Iran Connection: Model for Sunni Resistance,” The Washington Quarterly, Vol. 30, No. 1 (2007), pp.139-150.

86. Ghalioun, Towards a Strategic Vision for Iran-Arab Relations.

87. al-Mustaqbal, “Mashal: Iran Is a Model to Copy.”

88. Ghalioun, Towards a Strategic Vision for Iran-Arab Relations.

89. Ghalioun, Towards a Strategic Vision for Iran-Arab Relations.

90. Nedal Naʿisa, “Iran and the Arabs: Impossible Comparisons,” Al-Hewar al-Motamadin, (September 26, 2010), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.ahewar.org/debat/

91. “Iran is a Model for the Countries in the Region Regarding Energy,” Al-Alam, (September 13, 2011), retrieved August 24, 2014, from: http://www.alalam.ir/news/

92. Salam al-Rabadi, “Iran as a Model: On the Nature of the Strategic Planning,” Sawt al-Urubah, (July 9, 2012), retrieved August 24, 2014, from: http://arabvoice.com/32243.

93. “Zahar: I Call on the Arabs to Arm the Palestinian Factions Like Iran Does,” Al-Masry al-Youm, (November 24, 2012), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.almasryalyoum.com/

94. Marwa Abu Muhammad, “May 25 … Iran Won!,” Al-Wifaq, (May 25, 2014).

95. Khaled Kroom, “I Am Very Impressed with the Iranian leadership,” Islam Times, (May 11, 2011), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://islamtimes.org/

96. Omar Dhahir, “If Iran … Why Not?,” Arab Times, (December 27, 2011), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.arabtime.com/

97. Samira al-Attar, “Iran: A Political Model,” Al-Qabas, (June 26, 2009), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.alqabas.com.kw/

98. “Zarif: Iran Is Serious in the Nuclear Negotiations and the West Should Win the Confidence of the Iranian People,” Shafaqn, (2014), retrieved June 15, 2015, from http://iraq.shafaqna.com/

99. Oğuzhan Göksel, “Deconstructing the Discourse of Models: The Battle of Ideas over the Post-Revolutionary Middle East,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 15, No. 3 (2013), pp.157-170.

100. Tamer Magdy, “Morsi: We will Use All Means to Maintain Our Maritime Security,” Vetogate, (June 3, 2013), retrieved May 3, 2015, from http://www.vetogate.com/373498

101. Ahmad Ezzelarab, “Is Egypt Taking the Nuclear Path?,” Al-Wafd, (March 13, 2014), retrieved August 24, 2014, from https://alwafd.org/.

102. “Israel Attacks the Quest by Egypt and President Morsi to Acquire Nuclear Energy,” Al-Nahar, (April 28, 2013), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.alnaharegypt.com/t~

103. Mohammad Nasr, “Bastawisy: Morsi Wanted to Implement the Iranian Model,” Al-Wafd, (June 25, 2013), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.alwafd.org/502834.

104. Mohseen Abu Ramadan, “The Iranian Negotiations Experience and the Palestinian Lesson,” Al-Hewar al-Motamadin, (November 28, 2013), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.ahewar.org/debat/

105. Ahmadm Abdelkhalq and Ahmad Mokhtar, “The Iranian Experience with Support for Energy, Transportation, and Hygiene,” Al-Ahram, (July 27, 2012), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://massai.ahram.org.eg/

106. “Towards Taking Advantage of Iran’s Expertise in Meat Production,” Al-Helalia, (2011), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.helalia.com/

107. Salah Khalil, “Iran-Sudan Rapprochement: Goals and Ramifications,” Al-Ahram (May 1, 2011), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://digital.ahram.org.eg/

108. “Haitham bin Tariq: Examine the Possibility of Collaboration in Archaeology and Look at Iran’s Experience in Studying, Preserving, and Documenting Cultural Heritage Items,” Al-Watan,(2009), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.alwatan.com/

109. Israa A. Fuad, “Iran: Russia Officially Asked to Benefit from Teheran’s Experience in Coping with Sanctions,” Al-Youm al-Sabi, (May 10, 2014), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www1.youm7.com/News.

110. Shareef Nasr, “An Expert in Business Management Demands that the Presidency Implement the Iranian Experience in Reallocating Subsidies,” Al-Bawaba News, (April 7, 2014), retrieved August 24, 2014, from http://www.albawabhnews.com/