Institutions and organizations are affected by the changes and evolutions that take place in their environment. At their core, institutions are a mode of social relation. In the words of François Dubet, institutions are a mode of activity persisting as a relationship between multiple individuals2. In this sort of relationship, the roles of individuals are subject to change as processes evolve3. In the end, today’s widely discussed institutional/organizational crises –such as political party crises– are a consequence of changes in the roles of individuals in organizations as well as changes in the relational qualities of an institution. In this framework, the trend toward individualization is often emphasized. Personal interests are becoming increasingly crucial in defining organizational activity. In fact, organizations have come to be defined as arenas of competition between individuals. In economic terms, parallels are often drawn between the functioning of firms and political parties4. Weber defines political parties as political firms whose main goal is profit maximizing. Michel Offerlé offers an alternative definition to a political firm from Weber; for him the main goals of a political firm are “constructing” and “succeeding” but not profit maximizing. In this context, the concept of the political firm refers to the concept of political market. In this “abstract space,” competing actors broker exchanges in political assets in exchange for active or passive support.

In current political structures dominated by personal interests the logic of “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” can prevail and determine the shifting of alliances

In sum, political parties are a specific form of social relation formed to reconcile and coordinate society’s interests5. However, political parties should also be approached as arenas of conflict and competition. For this reason, we can take the political party as a unit consisting of both areas of accommodation and areas of competition, with these relationships constantly subject to change. Political parties are extremely fluid in terms of their ability to produce changing alliances and oppositions. Individuals on opposing “teams” can easily re-shuffle and work together at a different point in time. New alliances most commonly materialize during party congresses. In most cases, the power struggles at the center of a party are also reflected in the local party branches. At the same time, each set of relations is re-constructed at the local levels, meaning that party structure does vary between locales. In our fieldwork, we observed groups transform from virulent opponents to allies capable of working together6. For example, two friends who cooperated to win provincial elections parted ways when the ‘tape scandal’ broke out. These individuals competed with one another for a short period, only to join forces once again after the Kılıçdaroğlu leadership sidelined both individuals. These two individuals then went on to work closely at the extraordinary provincial congress summit. Another example of reforming alliances is evident in the changing alignments of the Deniz Baykal and Önder Sav factions. After the June 12th, 2011 elections, these former rivals united to oppose Kılıçdaroğlu’s leadership. Both these examples show that in current political structures dominated by personal interests the logic of “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” can prevail and determine the shifting of alliances. Furthermore, in many cases, we observe individuals coming to power with the help of a close circle, only to sideline these companions after acquiring power. We witnessed this sort of maneuvering for personal power in the case of an individual who won the nomination for municipal mayor with the support of province president and his group. When he found new allies to help him become a candidate for Parliament, he cut his old relation with the local province president and his group, and worked against them. For this reason, when we sat down to interview party leaders we found that the following view prevailed: “In politics nobody is your friend, or your enemy, forever”7.

The spring of 2010 witnessed the inception of a process that would lead to some significant changes for Turkey’s oldest political party

The CHP has been presenting itself for some time as a party going through the process of reform. In this paper, I would like to discuss the CHP within the paradigm of party individualization and “the political firm.” In what ways has the CHP made a break from its past? In what ways has it maintained considerable historical continuity? In short, just how new is the “New CHP?” Working from Weber’s concept of the political firm, examining the CHP in this framework has become even more crucial in light of the recent election results.8 After all, these election results provide a good indicator of just how convinced the public is of the CHP’s “renewal.”

In this paper, I will be working from two reference points as I evaluate the continuities and ruptures displayed by the “New CHP”: election campaigns and discourse of the CHP, and organization and leadership. But before moving into my analysis, it is worthwhile to provide a short overview of what the CHP has been up to for the past year and a-half. After all, these were the developments that brought about the claims of a changing “New CHP,” and its “changing ideological axis” to the fore.

The spring of 2010 witnessed the inception of a process that would lead to some significant changes for Turkey’s oldest political party. Until this period, two heavyweights dominated the party leadership, Chairman Deniz Baykal and General Secretary Önder Sav. However, the competition between these two men for control of the party’s organization had become increasingly apparent during the past few years. In 2008, a new party charter9 was passed. It reduced the General Secretary’s authority, dividing his former areas of responsibility among a handful of Assistant Chairmen. This development was widely interpreted as an attempt to dilute Secretary Önder Sav’s weight in the party. Secretary Sav must have interpreted these changes in much the same way, judging by how forcefully he resisted the new amendments.10 The previous charter stipulated considerable authority for the General Secretary, shaping the contours of intraparty competition around the Chairman and the General Secretary. Shifting alignments within the party could be sorted according to whether they were part of the Önder Sav faction or not. Of course, there were also groups who were disgruntled and excluded. On May 7, 2010 a video was leaked on the internet, which allegedly documented a relationship between Deniz Baykal and a former member of parliament from Ankara, Nesrin Baytok. Three days later, on May 10, 2010 Deniz Baykal announced his resignation at a press conference amongst tearful displays of party loyalty from party’s top leadership (See pictures 1 and 2). This was the beginning of a total restructuring of power relations within the CHP. With only days remaining until the 33rd Party Congress, Cevdet Selvi took over as steward of the chairman’s seat, but it was clear that all of the strings were now squarely in the hands of Önder Sav, the man who stood to lose considerable authority under the party charter amendments. After a short period of “palace intrigue,”11 Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu was elected Party Chairman on May 22-23, 2010. Kılıçdaroğlu was regarded as a symbol of change for the party due to his roots in Tunceli, his Alevi identification, his humble appearance, his reputation as a crusader against corruption, his distance from the nationalist wing of the party, etc. Kılıçdaroğlu’s persona was practically a summary of what the “New CHP” stood for. This gave hope to the party’s internal critics and brought a number of Alevi groups back to the CHP.

Pictures 1 and 2: Bihlun Tamaylıgil, Savcı Sayan and Canan Arıtman break into tears while listening to Deniz Baykal give his resignation. Milliyet, May 11, 2010.

These shake-ups did not end with Kılıçdaroğlu’s assumption of the chairmanship. The new leadership terminated a group of CHP province leaders with known ties to Baykal (Adana, Ağrı and Hatay) and forced the province leaders in Samsun and Izmir to resign12. At that juncture, Önder Sav began to see himself as the “guarantor,” even the “proprietor,” of the party. His followers took a similar stance, naming Sav the “savior of the party.” As this dynamic played out, a legal intervention added another shock to the power balances in the party. Previously, Attorney General Abdurrahman Yalçınkaya had sent an official notice that the CHP must implement the 2008 party charter. However, General Secretary Sav managed to block this notice from reaching the Office of the Chairman. Discovery of this obstruction was the beginning of the end for the party’s number-two man. Without going too much into details, it is important to note that the new charter went into effect, followed by a new party leadership with Gürsel Tekin taking Sav’s place. This effectively sidelined Önder Sav and his faction. In this way, the “New School” neutralized the “Old School” in two moves. From here onwards, the party leadership, headed by Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, increasingly rallied behind the “New CHP” slogan. As this new current found its footing, the “New CHP” and “a CHP for everyone” became the banners of the June 12th, 2011 campaign.

The “New CHP” was first articulated in response to concerns over party criticism during the Deniz Baykal-era

How do we read in political science this “New CHP”? As I mentioned above, we can approach this innovation by examining the election campaigns and discourse axis, as well as the organizational and leadership axis.

On the “New-ness” of the Election Campaigns and the Discourse

As power relations change and re-mold, political parties will occasionally face the need to reform as well. These changes can come in the form of new programs or charters, changes in discourse, organizational restructuring, or name changing. I will clarify this point with a few examples. Consider, for instance, how the organic ties between the French Communist Party and the General Labor Confederation were severed with the collapse of socialism. Today, left parties are especially intent on participating in the rise of social movements and on reforming in response to the young activists’ criticism of old hierarchies. One example is evident in the French Revolutionary Communist League decision to change its name to the New Anti-Capitalist Party, a clear response to the rise and spread of the anti-globalization movement. It is especially telling that the party decided to include the term “New” into their party title. Classical organizations are increasingly facing criticism from young activists, due to the hierarchical structure of these old organizations. For this reason, many left parties are moving toward a more diffuse model of party organization.

So what kind of outlook does the title “New CHP” reflect? What is this “New” terminology a response to? The “New CHP” was first articulated in response to concerns over party criticism during the Deniz Baykal-era. This processes gained momentum as CHP members studied the literature of European Social Democratic parties and even attended their meetings. A major guide in this process was a twenty-page pamphlet, which was edited by Andrea Nahles and published by the German Social Democratic Party. Entitled Building The Good Society: The Project of The Democratic Left, this pamphlet covered topics such as personal freedom, environmentalism, and sustainable development. During this period, CHP experts attended German Social Democratic Party meetings. In this way, the “New CHP” first materialized as an attempt to construct a democratic left in Turkey by following developments abroad, a development that a considerable segment in Turkey looked upon with high hopes. So why did these hopes fade as the CHP approached the June 2011 elections and why did these elections produce such disappointing results? In other words, why was the “New CHP” unable to truly reform itself?

In both the Good Society and the CHP manifesto, the first notable emphasis is on individual liberty

The “New CHP” materialized as a response to criticisms leveled at the CHP concerning Deniz Baykal’s nationalistic leanings, the party’s ambivalence on the Kurdish issue, opposition to EU accession, aging cadres, elitism, and its reliance on secular middle-class voters combined with an inability/unwillingness to engage with the urban poor. The “New CHP” sent strong signals indicating willingness for reform on these issues. I will categorize the points of divergence between “Old” and “New” CHP under two headings: the “nationalist-secular line” and the “elitist attitudes and policies.” In this way, we will be able to evaluate the continuities and the changes in the party by examining election literature and policies. In the end, I will use these two categories to demonstrate how the “New CHP” ended up perpetuating the old party line.

Picture 3: CHP Election Logo

“A country of freedom and hope. A Turkey for Everyone.” The CHP’s 2011 election manifesto begins with these words and continues with what became the elections’ most widespread CHP slogan, “CHP, for everyone.” At first glance, it may seem natural that a political party would aim to embrace everyone in society. However, it is crucially important that we discuss the significance of this statement in a political science context. But I will save this discussion for the section that covers the CHP as an organization. Right now, I would like to examine the main principles of the CHP’s election manifesto. According to the manifesto, the societal model envisioned by the CHP is based on the following principles:13

“For liberated individuals,

For sustainable development,

For social justice and humane living,

For a happy society and a happy countryman,

For contemporary living standards and a developed urban society,

For a just and secure world.

CHP, for everyone...”

It should be apparent that all of these principles and aims are taken directly from Building the Good Society.

“The foundation of the good society is an ecologically sustainable and equitable economic development for the good of all” (Good Society: 2)… “The good society is about solidarity and social justice. Solidarity creates trust, which in turn provides the foundation of individual freedom”14

In both the Good Society and the CHP manifesto, the first notable emphasis is on individual liberty. In the 2011 CHP pamphlet, this emphasis on personal liberty replaced the primary emphasis on secularism that characterized both the 2007 and 2009 CHP election manifestos. In fact, in the 2011 manifesto, secularism is not mentioned as a principle until page 18. In a major discursive shift for the CHP, the 2011 manifesto uses language from the Good Society pamphlet, which embraces “recognizing and respecting differences of race, religion and culture.” The CHP’s 2011 manifesto goes on to outline its vision for a pluralistic and democratic society in its section headlined “Respect for differences and pluralism.”

The CHP displays another important development in its approach to the Kurdish issue, which it approaches in the 2011 manifesto as a question of democratization, a stark departure from the 2007 manifesto, which treated the Kurdish issue exclusively within the scope of counterterrorism. The CHP’s election promises to Southeast Turkey can be summarized as follows: ending coercion in the region, bringing social reconciliation, allowing Kurds to overtly express their identifications, investigating unsolved political murders, allowing for language classes in a mother tongue other than Turkish, opening the Dersim archives and turning the Diyarbakır prison into a museum. Although these promises were expressed somewhat tentatively, they demonstrate a departure from the abstract Rousseauian understanding of citizenship promulgated by the CHP in the past. This represents a concrete step toward a pluralistic model of citizenship that recognizes identities as living objects in the public sphere.15 However, the creeping ambivalence almost immediately shows its face in the following lines, which refuse to go as far as allowing native-language education and instead opts for separate language classes in non-Turkish languages for interested students. Of the seven CHP pledges in this section, four are purely symbolic. The pledge to turn Diyarbakır prison into a museum is one such example. What is more, the CHP’s outline for a pluralistic society – the pledge with the most potential significance – remains obscure in terms of its content as a framework for a pluralistic society.

One of the main reasons the CHP has avoided clear proposals is that it still fears a backlash from the party’s “nationalist” base. Even these watered-down proposals were a cause for controversy among the base. The “New CHP” is trapped in the same contradictory position the AKP faces regarding the Kurdish issue. The AKP’s nationalistic strain is a considerable distance from supporting the policies of the “Kurdish Opening,” putting the AKP in a serious dilemma it has yet to overcome. In the recent election, the AKP used a remarkably sharp nationalist discourse in order to preserve this base. On the other hand, the CHP “tried to bring the stone throwing youth in Hakkâri together with the mini-T-Shirt wearing woman who throws stones at BDP convoys.”16 This led to considerable tension with the nationalist base, a key factor in Kılıçdaroğlu’s inconsistent positions and amorphous rhetoric.17 The ambivalence that is palpable in the party platform turned into a hopeless knot of contradictions in the Chairman’s discourse leading up to the elections. In today’s Turkey, a party that wants to attract votes from everyone will have trouble holding the same position in Hakkâri, Izmir, and Muğla. In a country with rising societal polarization, simply pandering to both sides is no recipe for winning votes. Upon returning to Ankara, Kılıçdaroğlu ended up having to go back on many of the statements he made on the campaign trail. This may have worked in an apolitical, non-ideological setting, but the Kurdish population is extremely politicized, rendering this strategy largely ineffective. This is why the CHP failed to win the Kurdish vote.

In approaching the Kurdish issue, the CHP kept its focus on East and Southeast Anatolia’s economic underdevelopment.18 This is characteristic of the CHP’s traditional approach and actually stands as a point in favor of continuity. On a rhetorical level, the party has come back to the line it held in the 1989 report drafted under the SHP while Deniz Baykal was General Secretary. This could be interpreted to indicate that - from an organizational perspective - the “New CHP” is actually an extension of the earlier SHP-era, with the nationalist Baykal era marginalized and even abandoned. However, it remains a fact that the New CHP is still unable to break free from Baykal-era nationalism. CHP discourse actually demonstrates considerable continuity from 1989 until now, in terms of its focus on the Kurdish issue as a regional, economically rooted problem as well as in the CHP’s reluctance to use the term “Kurd” in reference to the issue.19 Despite the inconsistent message on the part of Kılıçdaroğlu, the CHP has yet to go beyond its traditional parameters on the Kurdish issue. The CHP discourse completely reverted to its old patterns after the election when violence between the military and the PKK increased and the ruling party opted to harden its political line. We could actually go further and claim that this harshening policy actually rescued the CHP from some of the internal contradictions it had previously faced.

It should be underlined that the tension created by the “Ergenekon candidates” was not restricted to the party, it also led to a crisis in parliament over the swearing of the newly elected Members of Parliament

Another indicator that the CHP never fully managed to extinguish its “nationalist” current is evident in the “Ergenekon candidates” controversy. In order to appeal to the nationalist vote, the CHP used the Ergenekon case as springboard for criticizing the AKP on rule-of-law issues during the election. This provoked resistance from the party’s left. For example, Sinan Aygün’s candidacy caused an uproar within the party, leading to outright disputes in the Party Assembly. Some candidates even protested the candidacy of Aygün by resigning. Nevertheless, after a display of staunch support on the part of Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, Sinan Aygün made it onto the candidate list. Kılıçdaroğlu can in no way be considered part of the CHP’s “nationalist” wing, meaning that the presence of the Ergenekon candidates on the list is not solely a reflection of nationalist preferences. Mehmet Haberal’s candidacy in Zonguladak was a separate cause for controversy. In 2009, the Fethullah Gülen Movement withdrew its support for the AKP in several Zoguldak provinces, shifting the vote to the CHP20. Mehmet Haberal’s candidacy must have caused the Gülen Movement to reverse this decision, because in the last election the CHP was unable to win the expected number of votes. It should be underlined that the tension created by the “Ergenekon candidates” was not restricted to the party, it also led to a crisis in parliament over the swearing of the newly elected Members of Parliament. The CHP entered this boycott without making prudent strategic calculations, leading to a crisis that affected national politics and created a major rift within the party. The deadlock was eventually broken with AKP support, after rumors began circulating that some of the new CHP elects were planning to be independently sworn in.

The CHP’s elitist structure is another area where the “New CHP” attempted to make a break from the past. The new leadership’s basic response to this imperative consisted of a strategy which focused on “embracing the people.” This approach was modeled on the success of Islamic parties, especially the AKP. Its central mantra was that “every touch leaves a mark,” aiming for a model in which party leaders interacted and engaged with voters.21 Actually, veteran CHP observers will remember that some similar signals of change were emitted during the Deniz Baykal era. After the 2009 local elections, the CHP held an extended meeting of provincial leaders. At this meeting, the Baykal cadres were called to improve efforts to “embrace the people” by attending weddings and funerals. This strategy had shown demonstrable success during the election when it was tested in areas such as Zonguldak. The strategy of “engaging face-to-face” with people was not conceived during the Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu period. Instead, it was perpetuated in a way that increased its visibility. Whether Kılıçdaroğlu’s CHP instituted this strategy naturally and effectively is an open question. I can say from the events I attended and observed that some candidates were less than eager to mingle with the people during the election. In fact, some showed a total distaste for the exercise, performing their duties artificially and disingenuously. For this reason, the strategy of “embracing the people” was never fully internalized.

A prominent view arose among a segment of the party, which held that the CHP was trying to create another AKP, both in its approach to foreign affairs and with its domestic policy and strategies

The party’s rhetorical and strategic reform attempts clearly adopted the AKP model in some respects. This led some groups - and not just by the party’s nationalist wing – to conclude that the new leadership was attempting to turn the CHP into another version of the AKP. According to these groups, the “New CHP” was a reflection of attempts by the EU and the U.S. to create a CHP according to their own democratic criteria, an exigency that arose for these outside powers after all faith was lost in the AKP. These concerns led some CHP members to distance themselves from the party during the last election, leading to a phenomenon that was described as “going AKP in order to escape from the AKP.” With the changes in the CHP’s leadership, an observable warming of attitudes on the part of foreign powers was evident, especially in Europe. Party dissidents interpreted this positive environment as the CHP surrendering to the U.S. and E.U. In this way, a prominent view arose among a segment of the party, which held that the CHP was trying to create another AKP, both in its approach to foreign affairs and with its domestic policy and strategies.

The “catch-all” party is a product of the transformation that mass ideological parties underwent after World War II, when the rise of the welfare state led to a reduction of ideological cleavages

In the end, we can describe the “New CHP’s” search for an identity as a transplantation of the social democratic programs in other countries. However, when these ideas and practices are imported from other countries, they ignore the country-specific political context.22 This can lead to varied results. A respected and popular norm in one country may not resonate in another. It is possible that taking the German Social Democrats or the British Workers Party as a model could result in an organizational and social harmonization, breathing life into the pages of an “academic paper” 23 and turning these ideas into concrete reality.

Party Organization and Leadership

In the recent election, the CHP placed a weighty emphasis on the notion that the CHP exists for everyone. Regardless of the accuracy of this pledge, it was featured prominently in both the party manifesto and in CHP advertisements. A photograph of Kılıçdaroğlu, full of aspiration, gazing toward the heavens was combined with the slogan “the CHP is a party for all,” presenting an image of a new leader determined to embrace everyone. Why did the “New CHP” highlight the emphasis on including “everyone” so boldly? How do we interpret the term “everyone” in politics? What does it mean for a party to embrace everyone, to exist for everyone? What sort of typology does the CHP fit into?

The Republican People’s Party (CHP) is a cartel party that attempts to appeal to every voter segment. The New CHP’s intellectual and organizational orientation was focused on implementing what has been termed the “catch-all” party model. It is becoming increasingly difficult to match parties to a single model. A party will often accommodate characteristics from several models under a single roof. And because typologies are based on both party organization and party financing, a party may employ one model in its organizational aspects and a different model when it comes to financing, or even a combination of models for both categories. In this way, the CHP is both a catch-all party and a cartel party. I will present a quick overview of the characteristics of both models in order to make my claim clearer. In the end, this explanation should open the door to a debate about which direction the CHP is heading.

The “catch-all” party is a product of the transformation that mass ideological parties underwent after World War II, when the rise of the welfare state led to a reduction of ideological cleavages. In this new structure, each party was situated closer to the center and the method for winning votes was breaking ideological ties and commitments to religious or ethnic groups. Here priority was placed on gaining votes, winning elections, and forming governments. This meant that these parties would consider the preferences of voters outside their constituency, a policy of vote maximization, which resulted in loosening ties with the voter base. For success in this model, a political party must orient itself toward the center of the political spectrum.24 According to the architect of this model, Otto Kircheimer, all “catch-all” parties display these basic characteristics:

- Lack of emphasis on party ideology,

- A strong central leadership in the organization,

- A smaller role for party members,

- Refusal to address a specific religious, ethnic, or ideological group,

- Cooperation with various stakeholders due to concerns over financing and elections.25

It is obvious that entering into relationships with multiple stakeholder groups will have a number of implications for party structure. Parties that answer to stakeholder preferences in their platforms are rewarded with both votes and financing, reducing the need for party member support. The need for party members wanes further as they are replaced by paid professionals.26 Additionally, as ideology loses its importance, the candidates themselves become the source for differentiation among parties, leading to greater attention to personal skill, management, and technical abilities.27

Let’s evaluate the “New CHP” based on the “catch-all” party criteria.

i. Ideological ambiguity

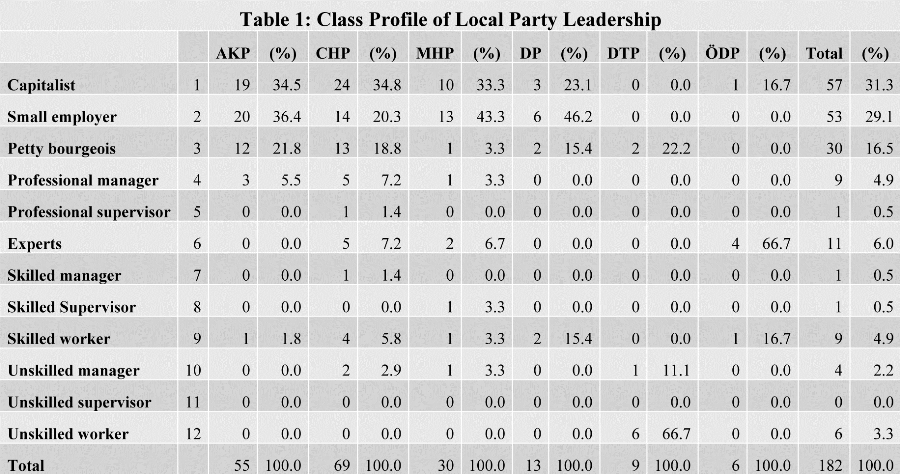

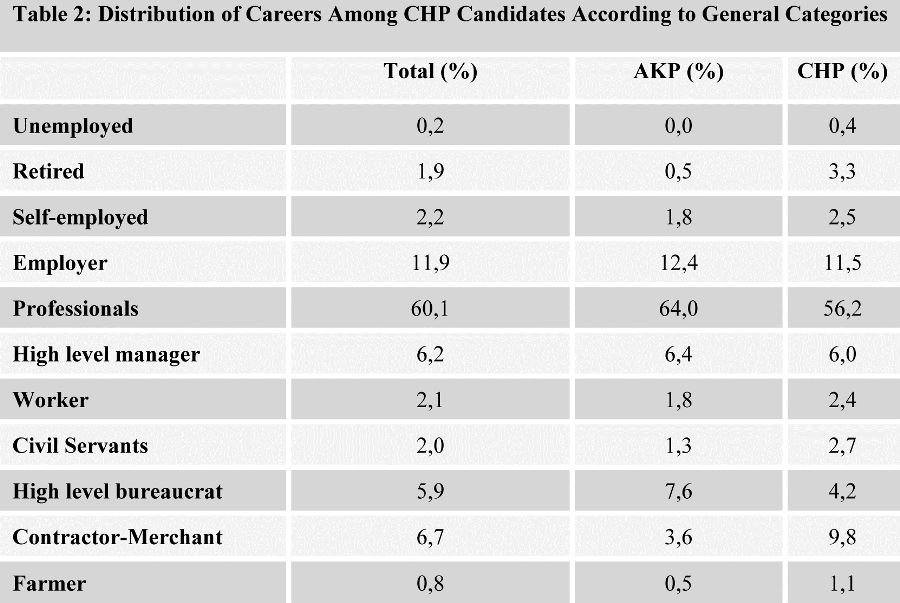

The “New CHP” party elites announced that the CHP was in the process of becoming a “true social democratic party” and attempted to craft a message that addressed all segments of society. In other words, the party tried to free itself from its ideological baggage, while at the same time attempting to install social democratic ideology. The CHP included candidates from the right in order to show their commitment to becoming a center party, leading to a series of self-contradictory episodes. Aydın Ayaydın’s attendance at the May 1, 2011 Istanbul rally was one of the most dramatic examples. Ayaydın was a candidate for the True Path Party (DYP), and was later elected as a candidate for the Motherland Party (ANAP) from 1999-2002. Ayaydın explained that this was his first time attending a May 1 rally in an article in which a picture of his raised fist was published.28 This sort of ideological ambiguity is one of the major causes behind this ebb-and-flow in CHP politics, a factor that is related to the obscurity of the social base upon which the CHP relies. This state-of-affairs continues to represent a serious dead end for CHP policies. A prime example of this dead-end adheres in the impossible task of answering to the preferences of businessmen - who are highly represented on the party executives and the party candidates lists (see table 1 and 2) - while at the same time, advocating for labor and the impoverished, the groups who are addressed in CHP campaign rhetoric. Although the actual class profiles of the party executives and candidates of MP, as shown in following tables, belong to the upper and middle classes, the discourse of party which is using family allowances projects and policies based on poorness discourses has put the party ideology in an unsteady place.

Source: Uysal & Toprak, particiler. Türkiye'de partiler ve sosyal ağların inşası, p. 57.

Source: Ayşen Uysal, “Compétition à multi-armes. Répertoire d’action des acteurs politiques

pour peser sur la sélection des candidats”, 11ème Congrès de l’AFSP, communication non publié, 31 août-2 septembre 2011a.

ii. Strong Central Leadership

“Catch-all” parties are based on a structure in which decisions are made at the party center, as the local organizations lose their importance, and a strong central cadre. As the party organization loses significance, it becomes as an election machine, and the leadership gains proportionally more importance. In other words, parties function as election machines, similar to the American model, whereby the party organization disappears, the campaign replaces the party organization, experts gain importance at the expense of party members, etc. Candidates emerge not as a function of their service to the party, but rather based upon their financial capacity, their name-recognition, and other similar factors. The principle of cursus honora, in which individuals advance based on service to the party, is set aside. This shift caused the largest volume of criticism and concern within the party during the run-up to the June 12th, 2011 elections. The policy of including “top down” names on the list at the expense of the old-names created widespread disgruntlement across a broad range of intra-party factions. The “New CHP”’s candidate selection process does display a number of “catch-all” party characteristics, with examples provided by the preference for financially well-equipped, media friendly candidates as well as for candidates from the world’s top universities (Harvard, Oxford, Cambridge, etc).

Some other indications of the waning importance of the party organization are the firing of several provincial chairmen (such as the chairman in Bursa29) as the election approached, the neutralizing of other provincial chairmen, and the failure to hold consultations on the local level when drafting the candidate list (as occurred in Izmir), etc. There are actually two reasons for this approach. First, the new leadership had limited knowledge and interest in organizational management. Second - and associatedly - the new leadership felt little need for local organizations and was confident it could manage affairs from the center.

The “New CHP” was similarly unable to mobilize its party members. The local leadership and party members faced a structure that largely ignored their preferences for candidates

With the organization pushed into the background, Kılıçdaroğlu’s “me” style of politics took the fore. Statements to the effect of “My name is Kemal, what I say goes” typified Kılıçdaroğlu’s approach, which consisted mostly of a series of public pledges rather than clear plans for how to achieve goals. These moves represented an attempt to create a “brand leader” like Tayyip Erdoğan with personal characteristics taking center stage. Special attention was placed on portraying the leader as a man of the people, a good sport, a trustworthy person, a family man, etc. As the party organization waned, the Kılıçdaroğlu “brand” became the face of the party and the CHP began to be run much like a large firm, with the party “CEOs” becoming brands as well. With the tremendous significance placed on the education, prestige, etc. of the top CHP leadership, it became clear that the CHP campaign was identical to a marketing strategy. Parallel to this development came the formation of a campaign concept focused on media attention, advertising, and so on. This campaign concept produces party dependence on financial resources, making the party ever more reliant on the business class. We can safely conclude that this factor was largely significant in securing the nomination for a number of candidates despite fierce opposition within the party.

iii. The declining role of the party membership

In our pre-“New CHP” fieldwork we established that, “membership-based organizations have declined in value for political organizations and party congresses have been reduced to instruments for nominating the party’s pre-determined delegate”.30 We can determine whether party membership remains important for a party by referencing whether the party makes an effort to attract new members as well as whether the party makes an effort to mobilize membership or developing new strategies and policies. Due to election of delegates who also elect party leaders and executives, every party leaders wants to affiliate new members who vote for him and by this way he reproduce his authority and power in party. For political parties, the sole significance of the membership lies in its function as an instrument for changing power relations within the party. In this power struggle, the membership becomes an “object” that can be added and erased without a second thought. This “objectification/ instrumentalisation” of the party membership turns members into something that party leaders only resort to when they “need” them (for delegate elections, political meeting, setting up election committees, etc). The “New CHP” represents a continuation of this party concept, obtaining new member registration in order to establish its own hegemonic position over the party organization. Because the General Congress is scheduled for October 2011, the new leadership places great importance on breaking the old structure and replacing it with a membership that will vote for delegates close to the party heads. Although there has been talk of completely re-registering all members (as was done in 1999), so far steps have not been taken in this direction. However, a new system has been introduced which will automatically regulate the payment of party dues via telephone. The purpose of this system is to make sure that members who have not paid dues are unable to vote for delegates.

The “New CHP” was similarly unable to mobilize its party members. The local leadership and party members faced a structure that largely ignored their preferences for candidates, even making choices in direct opposition to the local organizations and members requests. This pattern is only natural in an organization where the central leadership makes all the decisions and the elites are continually consolidating their hold. Needless to say, this state-of-affairs created a considerable rift between the leaders and the party membership. As the election approached, the CHP was unsuccessful in implementing the AKP model of mobilizing the base. A major reason for this failure is the refusal of the importance of the party membership, as it was seen as an apparatus. The practice of only turning to the members in electoral exigencies represented a failure to recognize the importance of fostering a sense of belonging and responsibility within the organization. This made pre-election mobilization on a mass scale impossible. At this juncture, the CHP’s management profile is characterized by a reliance on a cadre of electoral experts rather than on membership.

iv. Party revenues based on the principle of dependence

“Catch-all” parties rely on stakeholder groups for revenue. For this reason, stakeholder preferences gain priority in the party policies. In such situations, a party relying on business contributions will naturally be unable to conduct a pro-labor policy. Despite pro-labor rhetoric, the business interests constitute an insurmountable wall to bringing these pledges to fruition. This constitutes another internal contradiction within the “New CHP.”

Political parties cannot sustain themselves by relying on a single source of revenue. As a “catch-all” party - despite its dependence on stakeholders - the CHP remains highly reliant on state assistance. The rise in party dependence on state revenue has led to a new typology, the cartel party. R. Katz and P. Mair trace four stages, which political parties have undertaken since the 19th century. These stages proceed from the cadre party to the mass party, then to the “catch-all” party, and finally, to the cartel party.31 Because the leadership in a cartel party views politics as a profession, more experts are employed in the party. Almost every area of party activity - including elections - becomes the working area of party staff and experts. Advertising and public relations emerge as a sector at this stage and election campaigns witness a trend toward centralization32.

Because the CHP has reduced elections to a domain for expert activity and centralized control, displays the characteristics of a cartel party as well as those of a “catch-all” party. In fact, the two most noticeable changes in the CHP’s approach to the 2011 elections were the employment of experts for election campaigns and constructing a “brand leader” and the declining importance of the party membership. These changes point to a “New CHP” that is classifiable as a cartel party looking to attract votes from all segments of society.

Conclusion

So what lies in store for the future? Traditionally, the CHP is a party with one of the most fraught histories of internal discord. The deck is constantly being re-shuffled in the CHP. In this “political firm,” enemies routinely become allies and friends part ways without looking back. Because the CHP’s organizational structure greatly empowers the central leadership, a change at the top is unlikely, barring some kind of extraordinary development. At the same time, a growing sense of disillusionment, insecurity, and inertia prevails at the local level. If this pattern continues, the CHP will unavoidably be routed at the next local election. Going forward, we can expect the AKP to continue to expand, while its political opposition will be increasingly less effective.

Endnotes

- This paper is a product of TÜBİTAK’s research project entitled, The Construction of Turkish Political Networks. The Role of the Central Leadership and Local Functionaries in Forming Political Networks. No. 106K276. I would also like to thank Oğuz Topak for his contributions.

- François Dubet, Le Déclin de l’institution (Paris: éd. du Seuil, 2002).

- Virginie Tournay, Sociologie des institutions (Paris: PUF, Que-sais-je?, 2011), pp. 114-115.

- Max Weber, Le savant et le politique (1919), (Paris: UGE, 1986); Michel Offerlé, Les partis politiques (Paris, PUF, Que sais-je?, 2008 (1987).

- Max Weber, Economie et société (1921), (Paris: Plon, 1971).

- Ayşen Uysal and Oğuz Topak, Particiler. Türkiye’de partiler ve sosyal ağların inşası (Istanbul: İletişim, 2010), p.125.

- Uysal and Topak, Particiler. Türkiye’de partiler ve sosyal ağların inşası, p.142

- The result of the June 12, 2011 General Election: 49.8 % for the Justice and Development Party (AKP), 25.9% for the Republican People’s Party (CHP), 13% for the Nationalist Action Party MHP, and 6.5% for the block of candidates supported by the Peace and Democracy Party (BDP).

- At this juncture, the party had yet to determine the implementation date of the charter amendment, which passed on December 21, 2008. As we will discuss below, Önder Sav made considerable efforts to block its implementation after Deniz Baykal was ousted. But these attempts to block the charter ended up triggering Sav’s decline.

- Sav was initially able to block the new charter’s implementation, which was assigned in the congress. Still, Sav insisted on preserving the old charter, although the Attorney General gave a “warning citation” to the party. http://bianet.org/bianet/

siyaset/125822-chpde-tuzuk- kavgasi Accessed: September 18 2011. - For a detailed account of these ‘intruiges’ see Önder Sav’s interview in Ege’de Son Söz http://test.egedesonsoz.com/?

sayfa=roporta18j-detay&rID= 188&roportaj=sav%60in- agzindan--gandhi-kemal%60in-- dogusu , Accessed September 13, 2011. - Ayşen Uysal, “CHP ve parti içi demokrasi”, Radikal İki, July 20, 2010.

- See the CHP June 12, 2011 Election Manifesto, retrieved September 15, 2011, from http://www.chp.org.tr/wp-

content/uploads/secim_ bildirgesi-web.pdf. - Ibid., p. 5.

- See Füsun Üstel, Yurttaşlık ve Demokrasi (Ankara: Dost, 1999) for similiar discussions.

- Ayşen Uysal, “CHP Herkesi Yakala Partisi Oluyor”, interview with Neşe Düzel, Taraf, May 30, 2011.

- Ayşen Uysal, “Compétition à multi-armes. Répertoire d’action des acteurs politiques pour peser sur la sélection des candidats”, 11ème Congrès de l’AFSP, communication non publié, August 31–September 2, 2011.

- See http://www.chp.org.tr/wp-

content/uploads/dogu- guneydogu.pdf retrieved September 16, 2011. - For the reports, see. http://www.blogpare.com/

guncel-haber/shp-1989-kurt- raporu-tam-metin.html and http://www.chp.org.tr/wp- content/uploads/dogu- guneydogu.pdf retrieved September 15, 2011. - Uysal and Topak, Particiler. Türkiye’de partiler ve sosyal ağların inşası

- Jenny B. White, Türkiye’de İslamcı Kitle Seferberliği. Yerli Siyaset Üzerine Bir Araştırma, (Istanbul: Oğlak, 2007).

- Pierre Bourdieu, “Les conditions sociales de la circulation internationale des idées”, Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales, No. 145 (2002–12), pp. 3–8; Yves Dezalay and B. G. Garth, La mondialisation des guerres de palais. La restructuration du pouvoir d’Etat en Amérique Latine, entre notables du droit et « Chicago Boys », (Paris: Liber, 2002).

- With reference to the series of pieces published on September 13-14, 2011 in Milliyet.

- André Krouwel, “Party Models”, R.S. Katz and W. Crotty (eds), Handbook of Party Politics, (London: Sage Publications, 2006), pp. 256-258; R. Gunther and L.J. Diamond, “Species of Political Parties: a New Typology”, Party Politics, Vol. 9, No. 2 (2003–3), pp. 167–199.

- Krouwel, “Party Models”, R.S. Katz and W. Crotty (eds.), pp. 256–57

- Ibid: 257.

- Ibid., pp. 257-58.

- Radikal, May 2, 2011.

- Shortly after the Bursa provincial chairman was removed, he was re-elected in an extraordinary provincial congress.

- Uysal and Topak, Particiler. Türkiye’de partiler ve sosyal ağların inşası, p. 127.

- Richard S. Katz and Peter Mair, “Changing Models of Party Organization: The Emergence of Cartel Party”, Party Politics, 1995/1, p.10, retrieved September 11, 2010 from http://ppq,sagepub.com/

content/1/1/15. - Eser Köker, İletişimin politikası, politikanın iletişimi (Ankara: Imge Yayınları, 2007) pp. 22-23.