Since the landing of the UN Peacekeeping force in Cyprus – UNFICYP (UN Force in Cyprus) –in 1964 the Cyprus issue continues to be unresolved. Many scholars as well as journalists are weary of the endless discussions on Cyprus. It has become a real headache for many diplomats and a good number of politicians. Yet, it continues to occupy the busy agenda of the international community. It is common knowledge that there has been virtually no violence between the two communities of the island - the Greek Cypriots and the Turkish Cypriots – since 1974. In other words, this is the date when a Turkish military operation prevented the attempted unification of the island by the Greek “Colonels’ junta.” Both communities now live in their separated respective zones. They are split along a 180 km UN buffer zone from east to the west of the island, also known as the Green Line. The Greek Cypriots have been living in the southern part of the island under the internationally recognized state of the Republic of Cyprus, while the Turkish Cypriots live in the northern part of the island under the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, established in 1983 and only recognized by Turkey.

Since April 23rd 2003, several check-points were established through which the Turkish Cypriots and the Greek Cypriots have been able to cross to the other side by showing their ID cards or passports. In addition, since May 1st 2004, EU citizens have been free to cross without restraint from one side to the other side of the island by just showing their passports. Since the opening of the checkpoints between the two sides, fortunately there has been no significant inter-communal incident. This shows that, despite the political conflict, there is a level of civility between the two communities. If there is no violence or bloodshed between the two sides in Cyprus since 1974, then why do we need to “solve” the Cyprus problem, let alone talk about it? In other words, why does the Cyprus issue keep on appearing on the world agenda?

External factors combined with the mood in the current peace negotiations, suggest that the Cyprus problem is nearing an end game or at least a departure from a federation towards alternative solution models

The issue appears on the international agenda mainly whenever it is seen as an obstacle to a bigger international issue. Today, Cyprus issue is in the international agenda simply because it has been blocking or impeding bigger issues beyond Cyprus, such as Turkey’s EU accession, a meaningful institutional cooperation between the EU and NATO, and cooperation and stability in the Eastern Mediterranean – especially in the peaceful exploitation of the natural resources, such as gas and oil.

It is precisely these external factors combined with the mood in the current peace negotiations, which suggest that the Cyprus problem is nearing an end game or at least a departure from a federation – known as an established UN parameter for a solution – towards alternative solution models.

In this paper, I attempt to compare the common state and the common future – at least on paper – that the two leaders have been trying to create in the peace negotiations with what the public opinion on both sides view as acceptable and tolerable. In other words, first I evaluate the progress made by the two leaders in the peace negotiations as to how far they are from finalizing a comprehensive peace plan. Then, I assess where the public opinion on both sides of the UN divide stand vis a vis a comprehensive solution to the Cyprus problem. Based on the analyses of the problems or rather gaps - both on the leaders level negotiations and the gap between the public opinion of the two sides, I identify the main obstacles confronting a comprehensive solution to the Cyprus conflict. Finally, based on the overall analysis I speculate on future scenarios and propose recommendations that can help bring the conflict to a comprehensive settlement.

Seemingly Never-ending Negotiations

The inter-communal negotiations, which started in the 1960s, adopted “federation” as the future solution parameter in the second half of 1970s. Since then, the two sides have been negotiating – on and off – in order to establish – at least on paper - a federation that will be bi-zonal with regard to the territorial aspects, bi-communal with regard to the constitutional aspects, and one that will be based on the political equality of the two communities. Several on and off inter-communal negotiations and the proximity talks conducted under the auspices of the UN during the 1980s led to the UN Secretary General’s famous Set of Ideas (1992) – an overall framework agreement. However, the agreement was not adopted by either the Turkish Cypriot or Greek Cypriot side.

Towards the mid-1990s, the Greek Cypriot application to the EU for full membership began to draw support from the EU member states, due mainly to the successful policies and maneuvers of the Greek governments in the EU. In spite of strong Turkish and Turkish Cypriot opposition, the EU in 1995 turned a deaf ear to the Turkish Cypriot arguments and decided to open accession negotiations with the Greek Cypriot government – on behalf of the whole island. After that there was practically no peace negotiation until the 1999 EU Helsinki Summit where Turkey was announced as a candidate country. This changed the dynamics in the Cyprus equation. Here the idea was to solve the Cyprus problem before Cyprus joins the EU so that Turkey’s own EU vocation could proceed without Cyprus being a stumbling block. Hence, the two sides in Cyprus were motivated to start the inter-communal talks in 2000, which culminated into the UN Comprehensive Settlement for Cyprus - known also as the “Annan Plan” in 2004.

The Annan Plan was put to simultaneous separate referenda on both sides of the island on April 24th 2004. Though the plan was accepted by 65% of the Turkish Cypriots in the North, it was voted down by 76% - a huge majority – of the Greek Cypriots in the South. Here, the Greek Cypriot leader Tassos Papadopoulos, who advocated the NO vote for the plan believed that the (Greek Cypriot) Republic of Cyprus, which became a member of the EU without the Turkish Cypriot “partner,” would be in better position to use the EU leverage and get a much better solution for the Greek Cypriots than what the Annan Plan offered. However, that was not the case since the Turkish side refused to budge under this pressure and because the EU has been reluctant to play a decisive role in the Cyprus conflict.

During his tenure Papadopoulos was not interested in negotiating while his counterpart, the Turkish Cypriot leader Mehmet Ali Talat was eager to engage in negotiations aiming for a comprehensive solution. The presidential election in the Greek Cypriot community in 2008 became a battleground between the Papadopoulos’ NO camp and those who threatened that if negotiations are not pursued the island would be permanently divided. It was Demetris Christofias, the leader of the communist AKEL, who was elected. He oriented his campaign on the premise that Cyprus is at the brink of a permanent division and that he was the leader to negotiate the reunification of the island with his counterpart Mehmet Ali Talat – who comes from a (previously) socialist party.

After the Long Island negotiations, Ban Ki Moon wants the two leaders to reach the “end game of the negotiation” in 2012, preferably before July 1st, 2012 when the (Greek) Republic of Cyprus holds the EU term presidency

Talat and Christofias agreed in March 2008 that a number of working groups1 would be established on the substantive issues of the Cyprus conflict and prepared the ground for full-fledged negotiations that would be conducted by the two leaders. While the working groups were preparing the ground, the two leaders came together and issued two joint declarations on May 23rd and July 1st 2008.

According to the May 23rd 2008 joint statement, the two leaders:

reaffirmed their commitment to a bi-zonal, bi-communal federation with political equality, as defined by relevant Security Council resolutions. This partnership will have a Federal Government with a single international personality, as well as a Turkish Cypriot Constituent State and a Greek Cypriot Constituent State, which will be of equal status.

The two leaders made another joint statement on July 1st, 2008 where they agreed in principle that the common state would have single sovereignty and single citizenship, which is in line with the previous body of UN work. Since 2008, the two leaders have been negotiating on six dossiers – issues originally taken up by the six working groups. On February 1st 2010 when the UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon visited the island he read a joint statement on behalf of the two leaders:

It is our common conviction that the Cyprus problem has remained unresolved for too long. We are also aware that time is not on the side of settlement. There is an important opportunity now to find a solution to the Cyprus problem, which would take into full consideration the legitimate rights and concerns of both Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots. We are aware that such a settlement is in the interest of all and that it will finally bring peace, stability, and prosperity to our common home Cyprus. (emphasis in italics are authors’)2

According to the joint declaration dated February 1st, 2010, the two leaders are – at least on paper – stating that they were determined to solve the Cyprus problem, which in their common conviction had lasted too long. While pointing out the need to find a mutually acceptable solution that would take into consideration the legitimate rights and concerns of the two communities, the leaders are already referring to a common future for the two communities in their common home Cyprus.

From the joint statements of the two leaders as well as the UN chief’s statements, it is clear that there is a desire to create a common state and, hence, a common future for the Turkish and Greek Cypriots

After the Camp David style two-day intensive negotiations of the two sides under the auspices of the UN Secretary General in Long Island in late October 2011, it was clear that the two sides made significant progress on governance and power sharing3, European Union affairs and economic affairs. However, there is little progress on the property and territory issues, while external aspects of the security and guarantees require the inclusion of the three guarantor powers – Turkey, Greece, and the UK – into the peace negotiations carried so far by the Greek Cypriot and the Turkish Cypriot community leaders. After the Long Island negotiations, Ban Ki Moon laid down the UN scenario for the Cyprus issue. Ban wants the two leaders to reach the “end game of the negotiation”4 in 2012, preferably before July 1st, 2012 when the (Greek Cypriot) Republic of Cyprus holds the EU term presidency. He told the two leaders that he expected them to solve all the remaining internal issues of the Cyprus conflict by January 2012 when the three are scheduled to meet again. In such a case, Ban wants to call for a multilateral – sometimes referred to as an international - conference – where the three guarantor powers will participate to finalize the security and the guarantees aspect of the Cyprus issue. Here, the idea is to come up with a comprehensive solution plan to be put to the simultaneous, separate referenda of the two sides, so that hopefully with two YES votes this time – unlike the 2004 referenda, a united Cyprus will hold the EU term presidency. So, Ban, in his latest statement made things very clear:

Both leaders have assured me that they believe that they can finalize a deal. There is still work to be done. Their Excellencies, Mr. Christofias and Mr. Eroglu, have agreed that further efforts are essential over the next two months to move to the end game of the negotiations. My Special Adviser and his team remain ready to assist. I have invited the two leaders to meet with me again in a similar format in January next year. By then, I expect the internal aspects of the Cyprus problem to have been resolved so that we can move to the multilateral conference shortly thereafter.5

From the joint statements of the two leaders as well as the UN chief’s statements, it is clear that there is a desire to create a common state and, hence, a common future for the Turkish and Greek Cypriots. This is particularly evident at the level of the international community – symbolized by the UN, who has been hosting the inter-communal negotiations under its mission of good offices since 1968. It is also evident on paper, from the public statements of the leaders on both sides of in the UN divide in Cyprus. 6 The common state is described as a federal state that would be bi-zonal with regard to the territorial aspects and bi-zonal with regard to the constitutional aspects. The common future that is attached to the common state can be roughly described as a future relationship between the two communities where they will be politically equal – that is, one community would not be able to dominate the other or take the other one hostage. Furthermore, it is envisaged that the Turkish Cypriots and Greek Cypriots would respect the distinct language, identity and culture of each other in their common future to ensure stability, peace, and harmony. If this is the agreed upon common state and the common future at the political leadership level and the UN believes that this can be attained by bringing the negotiations to fruition, then are the two communities themselves ready for this? Here, I examine the Cyprus 2015’s (2010) survey7 results in order to understand if the common state and the common future endorsed by the two Cypriot leaderships – at least on paper – mesh with the aspirations of the two communities.

The Common State and Common Future Questioned by Public Opinion

According to the Cyprus 2015 poll, large majorities (68% GC, 65% TC) desire that the current negotiations will lead to a comprehensive settlement (Graph 1). However, equally large majorities do not believe the negotiations will lead to results (65% GC, 69% TC). When one takes into consideration that the inter-communal negotiations started in 1968 and have not yielded a solution yet, then it is only normal to expect that the people from both sides of the divide don’t have high expectations that a solution will soon be reached.

Graph 1: Level of Desire and Hope for a Solution

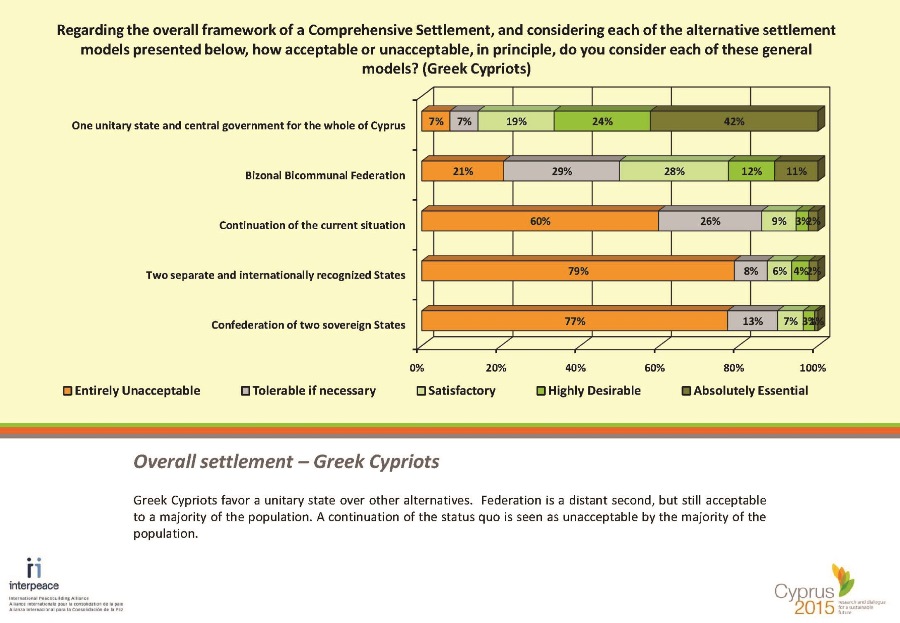

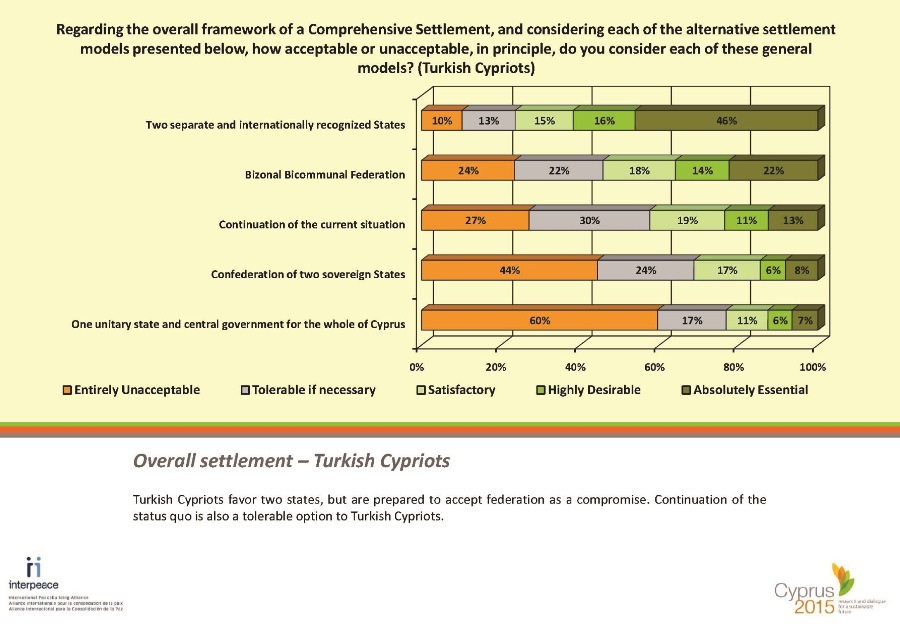

In Graphs 2 and 3, support of the Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots, respectively, to alternative settlement models are presented. Greek Cypriots favor a unitary state – sort of a Greek Cypriot nation state - over other alternative solution models (93% support). Federation comes as a distant second, but it is still acceptable to a majority of the population (79% support). Turkish Cypriots, on the other hand, favor two independent recognized states as a solution (90% support). However, they are prepared to accept federation as a compromise (76% support).

Graph 2: Alternative Settlement Models for Greek Cypriots

Graph 3: Alternative Settlement Models for Turkish Cypriots

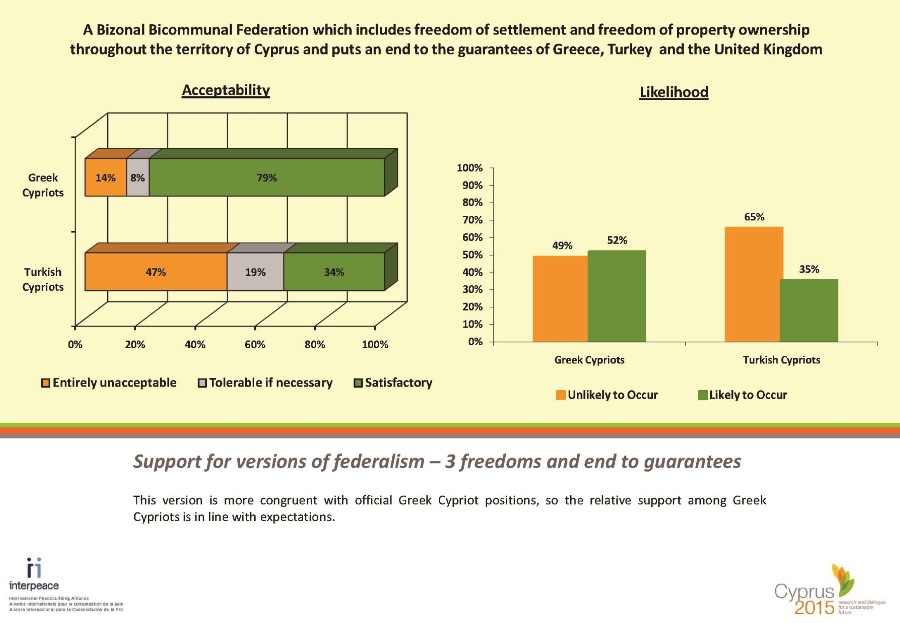

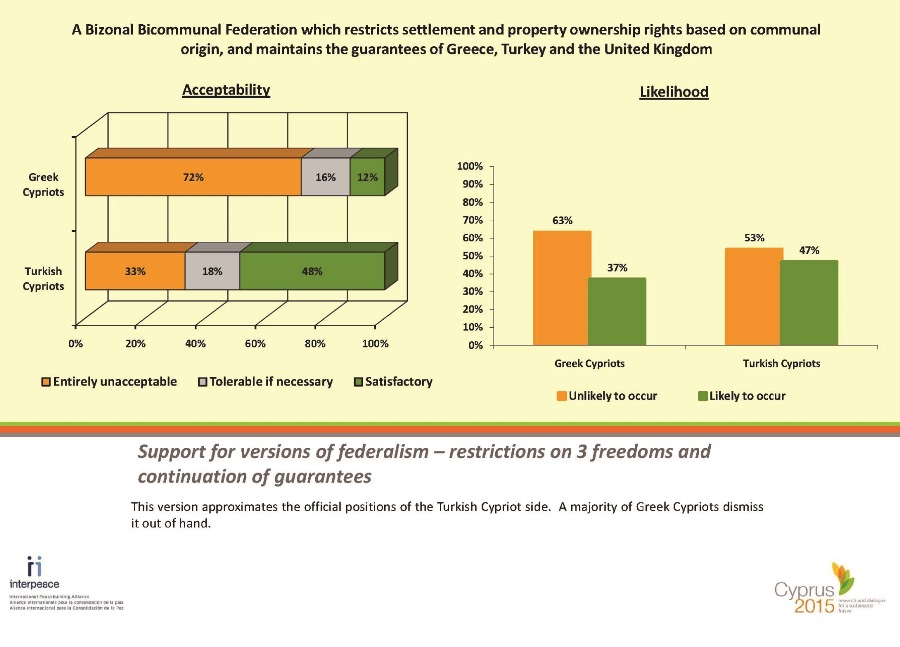

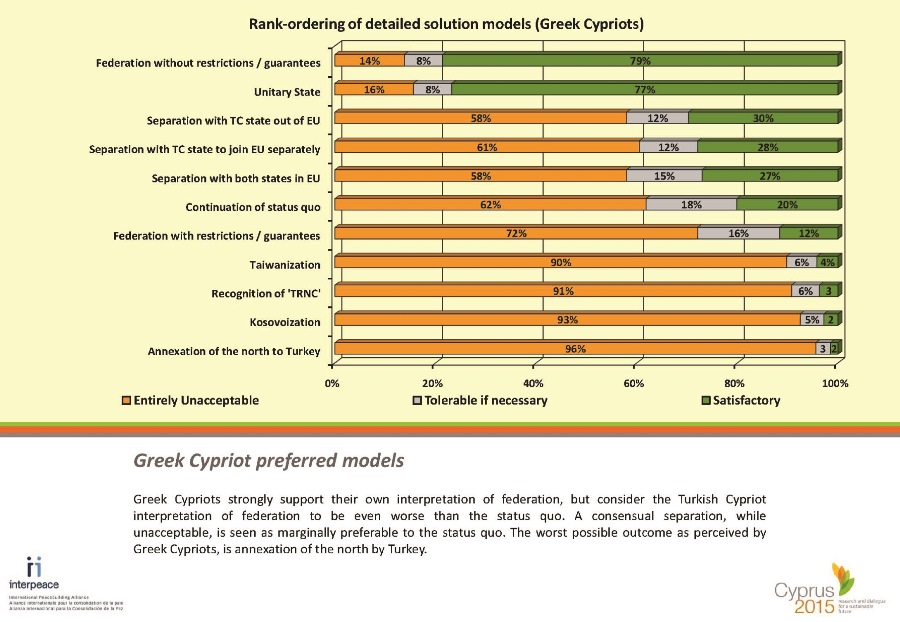

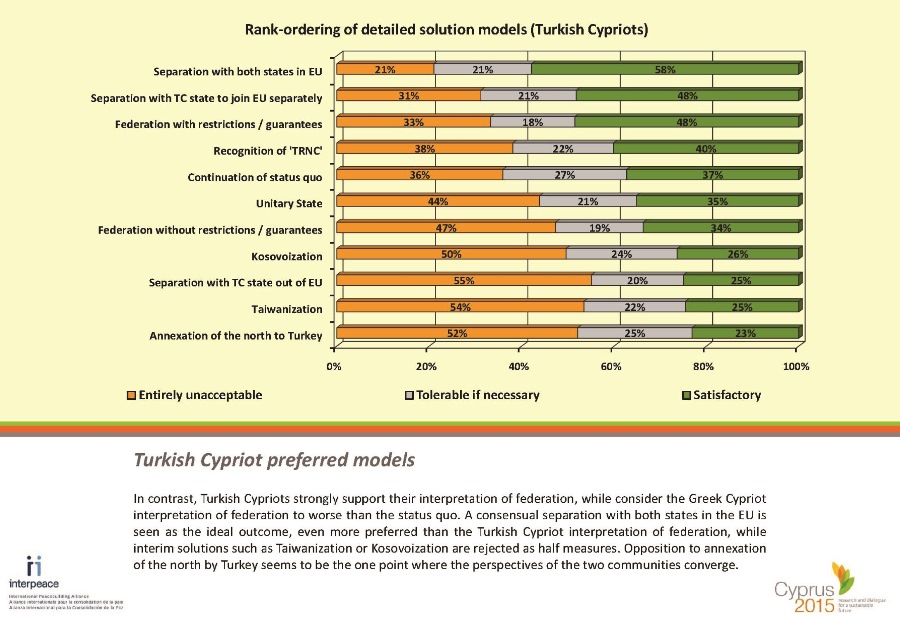

Greek Cypriots strongly support their own preferred model of federation (Graph 4) – that is, a federation without restrictions on settlement and property ownership throughout the whole island and without the 1960 Guarantees by Turkey, Greece and the UK – (87% support). The Greek Cypriots, however, consider the Turkish Cypriot preferred model of federation (Graph 5) – that is, a federation with restrictions on settlement and property ownership, as well as the continuation of the 1960 Guarantee system (28% support) to be even worse than the status quo (37% support). In contrast, Turkish Cypriots strongly support their preferred model of federation (66% support), while they consider the Greek Cypriot preferred model of federation (53% support) to be worse than the status quo (64% support).

According to the Cyprus 2015 poll, consensual separation scenarios, while unacceptable to a majority of Greek Cypriots, are seen as marginally preferable to the status quo (Graph 6). For Turkish Cypriots, a consensual separation with both states in the EU is seen as the ideal outcome (79% support) as can be seen in Graph 7. Consensual separation for Turkish Cypriots is even more preferred than the Turkish Cypriot preferred model of federation (69% support). However, interim solutions – sort of half-baked solutions - such as ‘Taiwanization’ or ‘Kosovoization’ are rejected as half measures (Graph 7). Interestingly, both sides are opposed to the annexation of North Cyprus by Turkey in the sense that that option is ranked last in both communities (Graphs 6 and 7).

Graph 4: Greek Cypriot Preferred Bi-zonal, Bi-Communal Federation

Graph 5: Turkish Cypriot Preferred Bi-zonal, Bi-Communal Federation

Graph 6: Rank Ordered Solution Models for Greek Cypriots

Graph 7: Rank Ordered Solution Models for Turkish Cypriots

Obstacles Impeding a Solution: Lack of Public Engagement in the Peace Negotiations

According to the Cyprus 2015 poll, there are several motivating factors for the two communities to desire a comprehensive solution to the Cyprus conflict. Among these factors, bringing Cyprus forward into a new era of long term sustainable peace (98% GC, 73% TC) and allowing Cyprus to be a normal state fully integrated into the EU without the Cyprus Problem dragging it down (86%, 65%). These are important motivating factors for solving the Cyprus problem. Economic factors are important motivating factors for both Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots, such as to create new business and job opportunities (89% GC, 77% TC) and to increase the potential for attracting foreign investment to Cyprus (84% GC, 69% TC). Greek Cypriots are particularly motivated by the prospect of achieving the departure of foreign troops from the island (98%) and achieving the termination of the guarantees and rights of intervention (96%). Turkish Cypriots, on the other hand, are not keen to see the departure of foreign troops from the island (31%) and the termination of guarantees and rights of intervention (25%). For Greek Cypriots allowing refugees to return to their homes is essential (99%) and recovering the control of towns and villages lost in 1963 / 1974 (98%) is quite important. For Turkish Cypriots, an end to their international isolation (76%) and enjoying the benefits of being EU citizens (74%) are significant factors to want a solution. However, there are very serious obstacles – constraining factors – impeding a solution in Cyprus.

A factor for both communities that leads to a lack of resolution in solving the Cyprus problem is the perception that the other side would never accept the actual compromises and concessions that are needed for a fair and workable settlement (84% GC, 70% TC). Subsequently, there is also anxiety that the other side would not honor the agreement and therefore implementation of the settlement would fail (82% GC, 68% TC). A political system based on power sharing between the two communities is not seen as desirable by either side (58% GC, 54% TC). There is a perception that through a settlement the other side might de facto end up controlling all of Cyprus (87% GC, 59% TC). Greek Cypriots fear that a solution might lead to a dysfunctional system of administration (63%). Whether real or imagined, both Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots express concern that after a settlement renewed violence may be erupt between the two communities (69% GC, 56% TC).

The UN Secretary General realizes that there is a dangerous gap between what the leaders have agreed upon during negotiations and how much the public is prepared to accept a comprehensive solution

Turkish Cypriots believe that too much time has passed with the two communities being apart and it is not possible for the two communities to live mixed again (53%). Greek Cypriots, on the other hand, are concerned that their community might end up carrying the burden of the cost of the solution and subsidize the other community (59%). Meanwhile Turkish Cypriots are more concerned that the cost of solving the property issue in a solution might be too high (52%). A vast majority of Greek Cypriots, on the other hand, would be discouraged in case the solution plan deviates from the implementation of human rights, European principles and European values (95%) or in case the solution plan benefits the interests of Turkey over the interests of Cypriots (96%). Last but not the least, according to the Cyprus 2015 poll, both communities are constrained in supporting a solution in case the solution plan does not create conditions of true political equality between the two communities (71% GC, 71% TC), though what “political equality” means for each side is quite vague.

A federal solution – sort of a win-win in a mutual compromise – has been mostly the second choice for both sides in contrast to their respective temptation to win unilaterally

The UN Secretary General realizes that there is a dangerous gap between what the leaders have agreed upon during negotiations and how much the public is prepared to accept a comprehensive solution. In other words, the UN chief politely reminds the two leaders that they have failed to prepare their respective communities to a final solution of the Cyprus problem by not informing them about the substance of the peace negotiations, and this carries inherent risks for future referenda on the Cyprus settlement. The UN chief, hence, urges the two leaders to prepare their respective communities to a comprehensive settlement by addressing their expectations, concerns and the perceptions, so that a catastrophe similar to the 2004 referenda will not be repeated.

Recent opinion polls continue to show that, while there is an appetite for peace in both communities, public scepticism continues to grow regarding the potential success of the ongoing negotiations in reaching a lasting agreement. Polls indicate overwhelmingly low public expectations that a settlement will be reached, as well as distrust on both sides that, if a settlement were to be reached, the other side would have any serious intention of honouring it. A solution, therefore, needs more than a comprehensive plan. It needs strong and determined leadership that will make the public case for a united Cyprus, with all the benefits this would bring.8

New Realities on the Ground

Although the leaders of the two sides have agreed – at least on paper - on establishing a bi-zonal, bi-communal federation, known as the established UN parameters for a solution in Cyprus since the late 1970s, this has not yet been possible. A federal solution – sort of a win-win in a mutual compromise – has been mostly the second choice for both sides in contrast to their respective temptation to win unilaterally.9 Winning unilaterally for Turkish Cypriots means having their own recognized independent state and solving the Cyprus problem through two recognized states in Cyprus. For Greek Cypriots, winning unilaterally means solving the Cyprus problem by establishing a Greek Cypriot unitary state for the whole island where the Turkish Cypriots will be a minority. It is quite clear that neither the stalemate has hurt both sides to the extent that they have decided to give up on their respective maximalist positions – first preference – and endorse their second best option – that is a federal solution, nor is the federal solution seen as providing enough rewards to move away from their temptation to win unilaterally. This is a vicious circle that constantly feeds the gap between the two leaderships as well as the gap between the public opinion of the two sides.

The strategy of the Greek Cypriot leadership in the peace negotiations has been to spread out the negotiations over time. To do so, it has refused a time-framework or a calendar for the peace negotiations, during which as an EU member state it can use the EU as leverage to put pressure on Turkey, an acceding country for EU membership, for concessions in Cyprus. In other words, the Greek Cypriot side tries to get concessions from Turkey in Cyprus, such as Turkey’s opening its ports to Greek Cypriot vessels or giving up territory (e.g., closed area of Varosha) to Greek Cypriots by tying these to Turkey’s EU accession criteria. Therefore, the Greek Cypriot policy is quite consistent with the Greek Cypriot public opinion, which firmly stands against making concessions on some of the key negotiation issues, such as the principle of bi-zonality, property ownership, guarantorship and so forth.10 Turkey, on the other hand, does not want to give concessions before a comprehensive settlement of the Cyprus problem or before lifting of the isolation measures imposed upon Turkish Cypriots’ travel, education, commerce, sports and so forth, which the UN and the EU promised in 2004 after the Turkish Cypriots supported the UN peace plan, but failed to deliver. Instead, Turkey faces a very tough accession process – if it could ever be called an accession process when more than a dozen chapters are suspended. This is partly because Turkey refuses to open its ports to Greek Cypriot vessels before isolation measures on Turkish Cypriots are lifted. The other side of the coin is the fact that countries like France, Austria, and Germany who do not want to see Turkey as a member of the EU precisely use Cyprus problem as an excuse to block or at least slow down Turkey’s accession process.

However, the Turkish side (Turkish Cypriots and Turkey), it cannot afford to say “NO” to a federal solution based on the established UN parameters – even though it is not its first choice. This is clearly observed today with the hardliner Turkish Cypriot leader Derviş Eroğlu continuing the peace negotiations, on the basis of the established UN parameters, where pro-solution leader Talat left off in 2010. The Turkish Cypriot policy is also consistent with the Turkish Cypriot public opinion. Nevertheless, compared to the Greek Cypriots, the Turkish Cypriots are more flexible on the negotiation issues.11

Since the 2002 election, when the AKP came to power, it has followed a new foreign policy orientation - a paradigm shift in Turkish foreign policy - that has never been experienced in this magnitude in the history of the Turkish Republic.12This new policy vis a vis Cyprus means Turkey’s continuous support for a solution in Cyprus based on established UN parameters: i.e., a bi-zonal, bi-communal federation based on the political equality of the Turkish Cypriot and Greek Cypriot sides.

For the AKP the moral superiority that Turkey, together with the Turkish Cypriot side gained in the international community by actively supporting the UN comprehensive peace plan in the 2004 referenda is invaluable. This was due to Turkey’s moving away from supporting the status quo on Cyprus and instead being the party that actively supports a solution based on the established UN parameters. Here, Erdoğan’s policies of ‘no solution is not the solution (in Cyprus),‘ (always) one-step-ahead (of the Greek/Cypriot side),’ and ‘win-win solution’ became the tactical guidelines of Turkey’s new Cyprus strategy that nicely and comfortably complemented Foreign Minister Davutoğlu’s ‘zero-problem-with-neighbors’ principle.

However, in solving any conflict it takes – at least - two to tango. In other words, both the Turkish Cypriot and the Greek Cypriot sides have to have the necessary desire and the motivation to solve the Cyprus problem. Nonetheless, it is clear that the Turkish government’s immediate tactic, as part of its bigger strategy in Cyprus, is to push the Greek Cypriot side to a solution based on established UN parameters. If that fails, the AKP government wants to see the Greek Cypriot side being exposed in the international community as the side who walked away from the negotiation table – in which case alternative solution models can be legitimately put on the table. The recent statement by Turkish Prime Minister Tayyip Erdoğan during his visit to North Cyprus for the 20 July Independence Day celebrations is very important, as it captures the new realities of Turkish foreign policy.

Making concessions in any issue is out of the question. Nobody should expect that from us… I’ve got four years as Prime Minister. I say this very clearly. For example, Güzelyurt (Morphou) is off the table. I don’t look at Güzelyurt the way we looked at the Annan Plan. Güzelyurt belongs to North Cyprus (unlike in the Annan Plan). Not even a single modification on Karpaz can be made. If they (Greek Cypriots) want to come for worship purposes, let them come (to Karpaz). We’ll sit down at the (negotiation) table differently. They (Greek Cypriots) still talk about what they can get on top of the Annan Plan. Sorry, but it is long gone. We say it very clearly. It should be a structure that will be bi-zonal and comprising of two states of equal status. If they accept it, fine, if not, it is up to them. Time is almost up… During the Greek Cypriot term presidency of the EU, we will never negotiate with them. Relations with the EU freeze. For six months there will be no Turkey-EU relations. We just watch the process from Turkey. Negotiating with the Greek Cypriots is out of question.13

Here, Prime Minister Erdoğan’s statements clearly reflects the over-confidence that the Turkish decision makers gained due to the enormous increase in the Turkish foreign policy profile since 2002 when the AKP first came to power. Compared to then, Turkish foreign policy’s scope has dramatically expanded and the Cyprus issue has dropped from the top of the Turkish foreign policy priorities to a lesser one. Through the press statement above, Erdoğan signals the following messages:

1. To the Greek Cypriot leadership: that it will be futile to use the EU leverage (as a member state) to gain concessions in addition to the Annan Plan. Turkey today is different from (and much stronger than) Turkey during the time of the Annan Plan. Hence, if the Greek Cypriot side prefers to stall, it will be to their own disadvantage, since a stronger Turkish side will have a stronger bargaining position.

2. To the European Union: that in a way Turkey is ready to have a showdown with the EU. It is clear that the Turkish government became quite (over-)confident due to its impressive economic performance as well as foreign policy successes in recent years, which brought the AKP government its 3rd successive electoral victory in June 2011. This combined with the already comatose relations with the EU due mostly to the constant procrastination of such countries as France, Austria, Germany, and (Greek) Cyprus in Turkey’s EU accession process, has already created a perception among many Turkish decision makers that the Turkey-EU relations need to be re-evaluated and put back on the right track – even if this means a showdown.

Future Prospects

Today, the irresolution of the Cyprus conflict causes serious obstacles to Turkey-EU accession negotiations. It also negatively impacts the establishment of meaningful EU-NATO institutional communication and cooperation. The recent tension in the Eastern Mediterranean between Turkey, Israel, and (Greek) Cyprus due to the oil and natural gas exploration of (Greek) Cyprus added one more variable to the intractability of the Cyprus conflict. Such external factors, in addition to somewhat weak domestic factors – i.e., the majority of Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots still desire a comprehensive solution to the Cyprus conflict,14 are increasing the need to resolve the Cyprus conflict. Given the above analysis, what are the future potential scenarios?

Scenario 1: Though the current peace negotiations have been very slow and they lack enthusiasm as well as a clear time-table, which the Greek Cypriot side staunchly refuses to put into place, walking away from the negotiation table would still be extremely costly. That is why neither the Turkish Cypriot side nor the Greek Cypriot side would want to leave the negotiation table. Hence, there is a possibility that the current peace negotiations might end up with an agreement based on the established UN parameters – that is, a bi-zonal, bi-communal federation based on the political equality of the two communities. According to the public opinion poll results, this is the second choice for both Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots.15 This scenario is what I call the “Belgium-ization” of Cyprus. Similar to Belgium, the two communities sometimes have problems establishing a common government and so forth, but manage their relations based on common denominators. In such a scenario, either this federation continues to exist for a long time – sort of a united Cyprus under the EU umbrella (membership), or after a certain time the two communities might decide that maintaining a common government is too costly and too difficult in which case they might opt for two states – what I call the Czechoslovakia-ization of Cyprus. In this case, the advantage is that the two sides can divorce each other without bloodshed and continue a civilized relationship under the EU umbrella similar to the Czech and Slovak Republics.

Scenario 2: In case the Greek Cypriot side leaves the negotiation table and this unilateral action is recognized by the international community, then the “federation” option would cease to be the only solution model championed by the international community (i.e., the UN and influential actors of world politics). In such a scenario, the links between North Cyprus and the rest of the world would be strengthened: In other words the relations would be normalized. This would lead to what I call Taiwan-ization and Kosovo-ization of North Cyprus – despite the lack of popularity of these models in the Turkish Cypriot community16. Taiwan-ization means, on the one hand, intensification of relations between North Cyprus with many states without formal recognition. Kosovo-ization, on the other hand, means the TRNC (Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus) will be recognized by a number of states, though just like Kosovo it will not be a member of the UN. This is because, some countries, like Russia as its foreign minister stated clearly “will not recognize the TRNC” in the foreseeable future.

Today, a bi-communal, bi-zonal federation based on the political equality of the two communities remains the only negotiated solution model having a chance to pass a referenda of both sides of the island

Scenario 3: There is a possibility – though very improbable - that the Turkish side will leave the current peace negotiations. In such a case, Turkey-EU relations will be severely strained and probably come to a halt. However, this would mean that Turkish Cypriots would continue to be isolated from the rest of the world. Under this scenario – which I would describe as the “dark scenario,” Turkey would move away from the EU and this would cause a real shift in Turkey’s axis. In other words, the outcome becomes Middle Eastern-ization and Islamist-ization of Turkey.

Among the three scenarios, the last one is the least probable one – but still a possibility that needs to be prevented. Because, such a scenario is against the interest of all the involved parties – Turkey, the two sides in Cyprus, the EU, and the international community at large. A Turkey slipping away from the EU will have less motivation to undertake further reforms in the area of democracy; it will have less incentive to solve the Cyprus problem; and it will fail to become a model of “consensus of civilizations” in the post-September 11 era, as well as a democratic model for the “post-Arab Spring” Middle Eastern and North African states, which will be a great loss for the international community at large. Hence, it is the responsibility of the European leaders to stop sending mixed messages to Turkey and work on bringing Turkey closer to the EU by judging Turkey through objective accession criteria, rather than through culturally and religiously biased lenses.

Conclusion and Recommendations for the UN

It is clear that neither the unitary state nor the two state solution the first choice of Greek Cypriots and the first choice of Turkish Cypriots, respectively, in the public opinion polls17 - are the likely outcomes of a solution based on the current negotiations. The current negotiations are carried out on the basis of the parameters that the two sides agreed upon, such as the 1977-1979 High level Agreements and the Joint Declarations of the Two Leaders dated 23 May and 1 July 2008. According to these agreed upon parameters, the solution of the Cyprus problem will be a federation with single sovereignty and citizenship, which will be bi-zonal with regard to territorial aspects, bi-communal with regard to constitutional aspects, as well as comprising of two constituent states of equal status – a Greek Cypriot State and a Turkish Cypriot State. This is a likely outcome if the two sides could be kept in the cooperative mode based on tit-for-tat strategy that they have been engaged since 2008 (Sözen 2010). Furthermore, based on island-wide public opinion poll results, it should be emphasized that a federal solution to the Cyprus problem – though second choice for both Turkish and Greek Cypriots – is a solution that is found by the majority on both sides of the UN divide as satisfactory, agreeable, and tolerable.18 Today, a bi-communal, bi-zonal federation based on the political equality of the two communities remains the only negotiated solution model having a chance to pass a referenda of both sides of the island.19

However, there is always the possibility of one side defecting – leaving the negotiating table or saying NO to an agreement in the referenda! Does that mean that the two sides would return to the status quo? Then the question is, is the current status quo sustainable?

The international community – through many UN Security Council resolutions and reports of the Secretary Generals made it clear that the status quo is not acceptable. However, in 2004 was that not also the case when the UN Comprehensive Settlement was voted down by the majority of the Greek Cypriots in the referenda? So, what will make the difference now? What needs to be done to get the two negotiating sides to end up in the federation (Belgium-ization) scenario?

A skilful mediator can induce the players towards cooperation, by means of utilizing binding agreements and/or side payments (reasonable financial and other gains). The mediator can get the conflicting sides to view and value the future differently. For example, a skilled mediator can increase the value of the discount factor for an iterated game, so that the conflicting parties are motivated not to quit the negotiation process. Hence, in the case of the Cyprus negotiations, the UN – having the mission of good offices – can do several things that can keep the two sides cooperating in the context of a tit-for-tat strategy20:

1. High-level UN officials should make frequent statements encouraging the two leaders; reminding them of their responsibilities and encouraging them to take bolder actions. Moreover, these statements should make it clear that the international community has very high expectations on the two leaders.

2. There should be a clear understanding that the price of leaving the negotiation table is very high (that is, if the punishment for defection is big, then cooperation becomes the choice). The UN should make occasional statements that it has been investing a lot on the Cyprus conflict and that there are other conflict-zones which need UN attention and resources.

3. The UN should find ways of creating and offering large side-payments to the two negotiating sides (the UN can try to change the payoffs of the game, so that through large side payments the payoff structure of the game can be altered so that it is no longer a Prisoner’s Dilemma game). For example, “donors conference” where funds are raised to be allocated to settle the property issues in the post-solution Cyprus can be a good incentive for the two sides to make mutual compromises.

4. The UN should commission research to investigate the optimal win-win scenarios for the different economic sectors in case of the federation scenario. Such research results should be disseminated to the general public in a simple and comprehensible mode.

5. The UN should try to induce the two sides to make binding agreements that should pave the way to a comprehensive solution. In other words, the UN should try to keep the two sides committed to the areas of convergence reached so far, so that even in case of defection, they will not start from scratch.

6. The UN should remind the two sides that in case the negotiations fail, it will make public the areas of convergence between the two sides as well as the positions of the two sides on the areas of dispute, based on notes taken so far – so that it would be clear as to which side stepped out of the agreed upon parameters.

7. It should be made clear that rejecting an UN-endorsed comprehensive settlement has a big cost for the side that rejects it. In case a comprehensive settlement emerges, it should be put to simultaneous, separate referenda – similar to 2004. Subsequently, the UN should remind the two communities that voting NO to a plan that was agreed upon by two leaders will have serious consequences that make the continuation of the status quo impossible.

8. The UN should remind the two sides that the UNFICYP cannot stay indefinitely on the island since there are other conflict-torn regions, which are in urgent need of Peacekeeping troops. It should be made clear that the failure of the current negotiations would probably lead to the withdrawal of the UNFICYP to be used elsewhere where it is needed more.

9. The UN should set out a realistic time-table for the end of the negotiations. There should be a few months between the end of the negotiations and the future referenda when the leaders go out into the public and campaign for the peace plan. A realistic time for the future referenda is some time before Cyprus’ EU presidency in 2012. Hence, the spring of 2012 should be set as the deadline to reach a comprehensive settlement.

10. In conjunction with the plan to end the negotiations at the beginning of 2012, the UN should upgrade its role in Cyprus – ASAP - from mere “mission of good offices” to a level where it can formulate proposals to bridge areas where the two sides could not reach a compromise.

11. The UN should get the two sides to engage in give-and-take among all the dossiers of the peace negotiations, except Security and Guarantees – which will be dealt with at the end with the presence of the three Guarantor powers.

12. In conjunction with the plan to end the negotiations in the spring of 2012, the UN should secure the approval of both sides that in case there are points of disagreement in a comprehensive solution plan – say a month before the end of the year – the UN will fill in the gaps. In other words, the UN will arbitrate at the very end-game.

13. In case of failure to reach an agreement in the first half of 2012 – which would mean the Cyprus issue would be put to the back burner until after the Greek Cypriot presidential election in February 2013, the UN – in consultation with the EU Commission, should work on a package deal that will include the following contested issues:

i. Opening of the fenced area of Varosha, starting its rehabilitation under UN supervision,

ii. EU’s direct trade for Turkish Cypriots through the port of Famagusta,

iii. Starting direct flights for Turkish Cypriots (Ercan could be “Nicosia Airport terminal B for the usage of both communities), and

iv. Turkey’s opening its ports to Greek Cypriot vessels.

In fact, implementation of such a package – that is accompanied/followed by a symbolic number of troop withdrawals by Turkey - would be a very important key to unlock many seemingly deadlocked issues with the EU, as well as be a very positive impact on the Cyprus peace negotiations.

Endnotes

- Six working groups were established: (1) Governance and Power Sharing, (2) Property, (3) Territory, (4) Economic Affairs, (5) European Union Affairs and (6) Security and Guarantees.

- SG/SM/12732 (http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2010/sgsm12732.doc.htm).

- There remains a major sticking point on this negotiation dossier, which is how to formulate the election in relation to the rotating presidency between the two communities. The Greek Cypriot side insists on “cross-voting,” while the Turkish Cypriot side prefers separate elections for each community similar to 1960 Republic of Cyprus.

- “Deal between Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot leaders is attainable – UN chief”, uncyprustalks.org, November 1, 2011.

- “UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon on the situation in Cyprus”, uncyprustalks.org, November 1, 2011.

- In April 2010, the Turkish Cypriots who were disappointed with the pace and the fate of the peace negotiations elected the hardliner Derviş Eroğlu as their President replacing Mehmet Ali Talat, whose flexibility during the negotiations failed to move Christofias to the necessary compromise. Eroğlu, however, continued the negotiations from where Talat left off. Since 2008, the leaders of the two sides have met for negotiations more than 100 times, yet without a breakthrough. Hence, today both Christofias and Eroğlu are questioned whether they truly endorse the established UN parameters for a federal solution to the Cyprus problem based on power-sharing between the two communities.

- Ahmet Sözen, Alexandros Lordos, Erol Kaymak and Spyros Christou, “Next Steps in the Peace Talks: An island-wide study of public opinion in Cyprus”, (Cyprus 2015), available at: http://cyprus2015.org/index.php?option=com_phocadownload&view=category&id=1%3Apublic-opinion-poll&Itemid=34&lang=en.

- “Report of the Secretary General to the Security Council,” S/2010/603, November 24, 2010.

- “Mutual compromise” and “temptation to win (unilaterally)” are game theoretic terminologies. According to Ahmet Sözen, “Towards a Comprehensive Solution in Cyprus: Breaking Away from the Prisoner’s Dilemma,” International Studies Association Conference (New Orleans, USA, 17-20 February 2010), the Cyprus negotiations can be seen as an iterated game. For more information about how Cyprus conflict and negotiations are treated in game theoretical framework see: Malvern Lumsden, “The Cyprus Conflict as a Prisoner’s Dilemma Game,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 17 (1973), pp. 7-32; Ahmet Sözen, “Cyprus Conflict: Continuing Challenge and Prospects for Resolution in the Post-Cold War Era,” (PhD Dissertation, University of Missouri Library, 1999); Birol Yeşilada and Joseph Hewitt, “Conflict, Negotiation, and Third Party Intervention in Cyprus: A Game Theoretic Analysis,” 1998 Annual Conference of the Midwest Political Science Association, (Chicago, 1998) and Birol Yeşilada and Ahmet Sözen, “Negotiating a Resolution to the Cyprus Problem: Is Potential EU Membership a Blessing or a Curse?,” International Negotiation Journal, Vol. 7, No. 2 (2002), pp. 261-285.

- Sözen, et al.,“Next Steps in the Peace Talks”; Spyros Christou, Ahmet Sözen, Erol Kaymak, and Alexandros Lordos, “Bridging the Gap in the Inter-communal Negotiations,” (Cyprus 2015, 2011), available at: http://cyprus2015.org/index.php?option=com_phocadownload&view=category&id=7%3Apublic-opinion-poll-july-2011&Itemid=34&lang=en.

- Sözen, et al, “Next Steps in the Peace Talks.“

- Ahmet Sözen, “A Paradigm Shift in Turkish Foreign Policy: Transition and Challenges,” Barry Rubin and Birol Yesilada (eds.), Islamization of Turkey Under the AKP Rule (Routledge, 2010).

- “Şartlar değişti artık taviz yok,” CNNTürk, June 19, 2011.

- Sözen, et. al, “Next Steps in the Peace Talks.”

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- See the press release on the results of the Cyprus 2015 poll (14 December 2010), available at: http://www.cyprus2015.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=75%3A

federation-remains-only-negotiated-settlement-but-public-skepticism-and-mistrust-remain-a-challenge&catid=3%3Alatest-news&Itemid=57&lang=en. - Sözen, “A Paradigm Shift in Turkish Foreign Policy.”