The “Arab Spring” and the Rise of the Military in Middle East Politics

One of the most controversial issues in the Middle East in modern times is the relation between politics and the military of a regional country. Civil-military relations have developed in a different and more complex form in the Middle East than they have in democratic countries due to the fact that the states in the region have been ruled through authoritarian means, and have experienced their modernization processes through their militaries; the mechanisms of their political administrations have been shaped through their militaries, but they still have failed to establish a military regime.

Milan Svolik, examining government changes under authoritarian rules between 1945 and 2002 in 316 cases, shows why the civil-military relation is crucially important in such regimes. According to Svolik, among the 303 leaders who lost power in the period, only 32 were removed by popular uprising and another 30 stepped down under public pressure to democratize. Twenty more leaders lost power through an assassination that was not part of a coup or a popular uprising, whereas 16 were removed by foreign intervention. The remaining 205 dictators were removed by government insiders, such as other government members or members of the military or security forces, i.e. as a coup d’état.1 This pattern is quite valid for the Middle Eastern countries.

The third period started in late 2010; militaries played a quite determining role when the nature of mass demonstrations began to change in a negative way. The most distinctive feature of this period is that mass uprisings have emerged as a new factor in the civil-military relations

Since the establishment of the countries in the Middle East, civil-military relations have been quite complex in nature; therefore, the two areas have become quite transitive. In such a picture, it is difficult to say that the balance is maintained between the two. Civilian-military relations became a pressing subject at issue again in late 2010 with the sparkle of protests that began in Tunisia and rapidly spilled over to other regional countries. The evolution of civil-military relations since the independence of the countries in the Middle East may be considered in three periods.2 The first one, which continued until the late 1970s, is the period of military coups, which are defined as “the infiltration of a small but critical segment of the state apparatus (military), which is then used to displace the government from its control of the remainder.”3

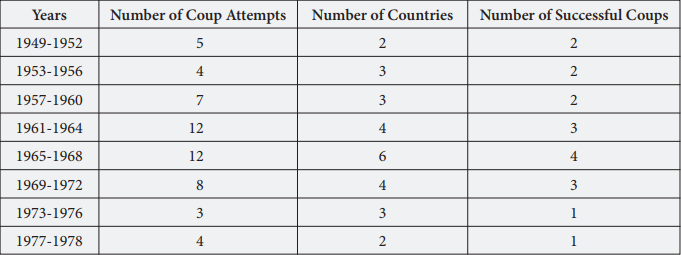

Table 1: Coup D’états in the Middle East (1949-1978) (country/year)4

As seen in Table 1, a total of 55 coups were attempted between 1949 and 1978. Military powers in the Middle East differ in their ways of using power, its effects, and the ruling typology.5 Regardless of their numbers and scopes, military coups are arguably the most critical determining factor in government changes in the Middle East. Therefore, when we consider this situation from the viewpoint of political leaders, as Feaver puts, “the need to have protection by the military may bring with it the need to have protection from the military.”5

The second period covers the time frame from 1979 until 2010, in which the civil-military relations were on a steady base and military interventions rarely occurred. In the three decades following 1980, successful coups numbered 17.6 According to Beeri, this period of relative political stability was achieved when elements toppled a government by a coup “took measures to prevent the same mechanism from being used against themselves.”7 Although this mechanism works differently in every country, it basically follows the same processes and lays the ground for the continuation of military tutelage in different forms within a country. It is possible to talk about a power balance between the military and political forces. In a sense, the military uses mechanisms of suppression and force against an opposition, when necessary; therefore, contributes to the longevity of the ruling order,8 and the political rulers, in return, clear the way for the military in the spheres of economy and politics. Such a form of relationship is not an indication of a sensitive balance between the two elements; to the contrary, as Cook says, the military rises in a position of “ruling but not governing.”9

The third period started in late 2010; militaries played a quite determining role when the nature of mass demonstrations began to change in a negative way. The most distinctive feature of this period is that mass uprisings have emerged as a new factor in the civil-military relations. The Arab Uprisings are a new phenomenon for the Middle East in terms of their quantitative and qualitative scopes, demands for political change and the points they have attained. Up until late 2010, despite the “waves of democratizations” over different periods, and the structural transformations in international politics, such as the end of the Cold War, the authoritarian regimes in the Middle East had remained in place; with the popular revolts, however, they arrived at the edge of change. In the face of the revolts calling for government changes, militaries assumed the guardianship of the rulers; as such, they were expected to confront the masses. Militaries were capable of such an intervention; however, the determining factor at that point was the willingness of militaries to act on their capabilities.10 Whether or not militaries are willing to take upheavals under control has always been one of the most critical issues that carry the transformation processes into different dimensions.

At the onset of the demonstrations in Syria in March of 2011, comments were made that the “change of government in Syria may be in stark contrast with those in Tunisia and Egypt.”11 In fact, military security units took action against the demonstrators in order to control the revolt and prevent possible breakouts from the military. The question at this point is, “Why did the military take action to protect the Assad rule in Syria?” This study elaborates the military’s desire to suppress the uprising in terms of its relations with the ruling order, analyzes military-political power relations in Syria, and explains the military’s attitude accordingly.

Military and Politics as a Power Bloc in Syria: From “Les Troupes Speciales” to the Uprising in 2011

The periodization on civil-military relations in the Middle East presents a clear-cut frame when Syria is at issue. The first term lasted from 1919 to 1946 during the French Mandate; the second mandate from 1946 to 1970 can be defined with the power struggle among the different ideological/sectarian groups within the politics and the military. Lastly, the third term started with Hafiz Al-Assad’s military coup in 1970 until the Syrian uprising began in 2011.

The French influence is a critical factor in shaping the roots of the Syrian regime. The League of Nations had formulated the mandate regime in 1919 to provide assistance to the developments of some communities in their independence processes.12In this connection, the French presence in Syria until 1946 created opposite outcomes. France’s political strategy, described as “minority politics,” kept different bonds of belonging alive insofar as to pursue identity politics. Such identity politics also constituted the main reason behind the power struggle in the military.

The power struggle that emerged in the power gap caused by Syria’s independence from France manifested itself the most in civil-military relations

The French administration preferred minorities while forming the Special Troops of the Levant and the Military Academies at Damascus and Homs –the backbone of the Syrian and Lebanese armies.13 Minorities considered participation in the military as a way of raising their status. The upper social classes consisting of Sunnis and influential tribes view the military as a place for the “lazy, underdeveloped, socially disadvantaged or influential yet clumsy.”14 The French minority politics, the adaptation of minorities and the disadvantaged to such politics, and the preferences of the upper class of the period led to the rise of minorities in the military.

Since the 1930s, in particular, Alewites gained ground in the military –albeit in low rankings– as Sunni Arabs organized even more for independence, and the French favored Duruz and Alewites.15 The influence of Alewites in the military became more visible in the 1940s. The percentage of Sunni Arabs in the military declined to 30 percent according to the population/military balance in 1947.16

Therefore, the military became an institution dominated by minorities in terms of identities and by lower social classes in socio-economic terms. As these military troops were transformed into the Syrian and Lebanese armies in 1945, the weight of minorities in the military composition remained unchanged. This factor would facilitate cooperation between the Ba’ath Party and the military, both of which were nurtured by the same human sources and were powerful in the same regions.

The Power Struggle and the Military Coups after Independence

Between 1946 and 1970, Gordon Torrey indicates that a total of 15 coups were made in Syria.13 The most effective interventions began with the Husnu Zaim coup in 1949, followed by the coups in 1951, 1954, 1961, 1963, and 1966, and ending with the military coup by Hafez al-Assad in 1970. This period should not be interpreted only as the reflection of a political power struggle within the military. The military was shaped by purges and through setting up new cadres. In this process of power struggle, the purging of various groups prepared the ground for minorities to gain strength both in the military and in the Ba’ath party; therefore, these two factors became the main components of the ruling power. What I have described as the “ruling bloc” emerged from the co-dependencies of these two elements in a mutually supporting manner.

With the Ba’ath coup in 1963, Syrian politics were presumed to have settled down to a paradigmatic ground. Despite the Ba’ath’s mission of ideological integration, full-fledged political stability was not completely achieved.

Hafez al-Assad established the Republican Guards in 1976 under the command of Adnan Makhlouf, his wife’s first cousin. The Guards drew their ranks from the Air Force –once commanded by Hafez al-Assad

The coups in 1966 and 1970 are an indication of an internal feud within the Ba’ath party. In fact, it was not simply a change of actors but rather a reconstruction of the regime in general –and the military in particular– when Hafez al Assad came to power via a military coup d’état in 1970. Assad survived the internal feuds in the regime and remained in power until 2000, at which point Bashar al-Assad smoothly took over the legacy of his father. The military protected the regime in the face of mass demonstrations in 2011. All these events pertain to the structure and functioning of the regime.

The power struggle that emerged in the power gap caused by Syria’s independence from France manifested itself the most in civil-military relations. At the time of independence, Arab, Kurds and Circassians, as the remnants of the Ottomans, in addition to Alawites, Duruz and non-Muslims, who gained strength owing to the French, were quite influential and competed with each other for power and influence.

Considering ideological tendencies crossing such an identity dichotomy, the rivalry within the military at this time became increasingly complicated by ethno-political polarization. In the authority gap caused by the lack of political harmony and leadership,17 a military intervention in politics took place in 1949.

One of the most significant results of the period of political instability between 1949 and 1963 in Syria was that minorities and previously disadvantaged groups became more effective actors in terms of the power struggle. Ekrem Hurani, a Ba’ath leader, worked diligently to include minorities in the military academies after independence, and that cleared the way for intensified relations between the Ba’ath party and military members.18 An important characteristic of the Ba’ath party was its effort to avert possible inter-party feuds among members in an ideologically suitable manner by eliminating ethno-political differences. However, this effort was hardly materialized. The distribution of military officers in 1955 reveals factions in the military, and the solidarity within each of but not among these factions can be seen clearly.

The ratio of Alawi officers in the Syrian army –particularly at lower ranks– stood at about 65 percent in the 1950’s. Sunni officers were fewer in number but occupied high-level positions.19 During the Zaim period, Circassians, and in the Shishekli period, Sunnis of Hama-origin rose in military ranks.20 This was one of the most important reasons why Sunnis held upper positions.

In the period 1946-1963, however, due to purging each other of Sunni blocs through coups, the possibility of cooperation among Sunnis disappeared, but the solidarity among military officers from the minorities endured. According to Pipes, as one Alawi rose through the ranks, he brought his kinsmen along to take his place.21 Thus, the identity composition among middle-ranked officers did not change as Alawi officers were promoted.

Organized by a group of military officers on March 8, 1963, the Ba’ath coup was the final showdown between the ideological or sectarian factions in the military. The power struggle would continue among Ba’ath actors from then on. It was a critical coup in two regards: Firstly, the coup was a critical turn in which, as Rabinovich remarks, “the army-party symbiosis”22 was achieved. The symbiosis was realized in two steps, the first of which being the purges after the coup (Alawite officers replaced ninety percent of the eliminated 700 officers),23 and the second of which was that these promotions were largely based on favoritism and nepotism; therefore, a certain faction took the army under control. Secondly, the army ranks and officers featured the Ba’ath –the foundational identity of the country and a political identity– rather than an ethnic or “Alawi” identity.24 Therefore, the party and the army were linked together and these two institutions became controllable by the same actor. However, that did not mean the end of cliques in the army. The coup in 1966 was a product of Duruz and Alawi cooperation, and Sunni actors who gathered around Amin Hafez were depleted. Although the power struggle continued after the 1970 coup, it was not effective in the face of Assad’s power strategies.

Hafez Assad and the Military: A Power Bloc

Hafez Assad acceded to power in an environment where, due to the fight for power and the 1967 fiasco, Syria was lacking bureaucratic institutions, coups were taking over the ruling of the country, national unity was not achieved although nationalist thoughts were high, and power struggles had become a chronic problem. Assad particularly valued the army in order to consolidate his power and bring stability to the country. The army was important because of the problems experienced with other countries, Israel in particular; besides, if left out of the political equation it could be a source of threat against Assad’s ruling.

Syrian army troops hold up portraits of President Bashar

Syrian army troops hold up portraits of President Bashar

al-Assad (L) and his late father, former president Hafez al-Assad, as they pull out of the southern protest hub of Daraa on May 5, 2011 after a military lockdown of more than a week during which dozens of people were killed in what activists termed as “indiscriminate” shelling of the town, some 100 kms south of the capital Damascus. | AFP PHOTO / LOUAI BESHARA

It may be claimed that Assad designed the army to meet two goals, as far as its functions are concerned. The first of these two goals was to secure the country against external threats. The Peace Agreement which Egyptian President Anwar Sadat signed with Israel in1979 deprived Syria of a key ally, Egypt; therefore, protecting Syria from external threats became one of the most important developments compelling Assad to expand his army. From this angle, it is not surprising that the number of soldiers in Syria prior to the 1967 war was about 50,000, but increased to 170,000 in 1973, 300,000 in 1982, and 500,000 in 1983.25

The second critical development was the protection of the regime “against internal threats,” which is a focus of this study. The Defense Units, the 4th Armored Division, the Republican Guards, and the Special Forces Regiment are the leading military units designed to shield the regime. Let’s look at each of these in turn.

Defense Companies: Under the command of Rif’at al-Assad, Defense Companies composed of 50,000 troops constituted a critical segment of the Land Force in Syria. Many troops of Defense Companies (90 percent)26 were selected on the basis of “close tribal links to Hafez al-Assad, an indicator to show their possible attitude in case of a crisis. In fact, Defense Companies undertook affective measures against the protests in Aleppo in 1980, and suppressed the Hama Riot in 1982, accomplishing this mission at the expense of tragic consequences. After the Hama Revolt, however, Rif’at attempted a coup by means of the Defense Companies when Assad had a heart attack. After Rif’at’s abortive 1984 coup, Hafez al-Assad dissolved the Defense Companies, transferring its personnel and equipment to the 4th Armored Division.27

The 4th Armored Division: The Division gained the attention of the public agenda particularly after the 2011 demonstrations evolved into an armed uprising. The commanders of the division between 2000 and 2011, Mahmoud Ammar, Ali Ammar and Ali Durgham were of Alawi origin,28 but Maher al-Assad acted as de facto Division commander, as he had in a similar manner in many other military units.29 Although it had a traditional army organizational structure, the Division served as one of the regime protection forces. The deployment of the Division in the Syrian capital of Damascus and the fact that almost all of the equipment of the Defense Companies were transferred to the Division indicate that it acts as the line of defense for the regime.

The Republican Guards: Hafez al-Assad established the Republican Guards in 1976 under the command of Adnan Makhlouf, his wife’s first cousin.30 The Guards drew their ranks from the Air Force –once commanded by Hafez al-Assad.

The Republican Guard was primarily oriented to counteract coup attempts and protect the Presidential Palace. Neither this mandate nor the lineage of its commanders changed during the Bashar al-Assad regime. All commanders are Alewites. In 2000-2011, the Guards were commanded by Ali Hassan, Noureddin Naqqar, Shou’eib Suleiman and Badi’Ali.31

The Special Forces were organized under Commander Ali Haidar against internal threats in the 1970s. The Special Forces served as a critical counterweight to Rif’at al-Assad’s Defense Companies during his 1984 coup attempt.32 Haidar did not share familial ties with Hafez al-Assad, but was a close relative of Adnan Maklouf. When Haidar objected to the possibility of Bashar’s succession in the mid-1990s, following the death of Basil in 1994, Hafez promptly relieved Haidar and arrested him.33Under Bashar al-Assad’s reign, Ali Habib, Sobhi al-Tayyib, Raif Dalloul, Joum’a al-Ahmad and Fouad Hammoude, all of who are Alawites, commanded the Special Forces.34

The restructuring of the army to protect the regime caused the regime to be labeled as the “Nusayrian regime,”35 but it would not be accurate to say that the regime is solely protected on the basis of Alawite military officials.36 Quinlivan states that the assessment of the Syrian regime through sectarian elements is not descriptive enough but instead one needs to focus on the strategies developed to protect the ruling elite. Such strategies, labeled coup-proofing,37 are the “measures to prevent coup mechanisms from operating against itself.”38

Such measures have been quite effective both in suppressing the Hama revolt and in circumventing Rif’at al-Assad’s attempted coup. Yet, these consecutive developments left those in power with a significant paradox: the lack of legitimacy for opponent groups increases the need for such military units. Rif’at al-Assad’s coup attempt signals that loyalty to Assad is not verifiable and guaranteed, but circumstantial. Therefore, military leaders who were in charge of the protection of the regime posed a threat against the Assad rule. Another important problem stemmed from such an institutional restructuring in the army is that the units formed against internal threats, in particular, lack discipline and have gradually turned uncontrollable. Many top-level military officers are claimed to have unlawful connections to earn more income. Illicit trading from Lebanon tops the list of such claims.39

Moreover, some top-level army and intelligence officers known to have close ties with Assad, in a similar manner, control 5 billion dollars’ worth of narcotics trafficking. Hafez al-Assad warned military officers through a public statement in 1984 and instructed them to take the border trade with Lebanon under control,40 and many officers were discharged from the army due to the allegations. Similar accusations and warnings were brought to the agenda again in 1993, giving the impression that illegal trading was routine and that many military officers profit significantly from such involvements.

The assassination of the Prime Minister of Lebanon, Rafiq Hariri, on February 14, 2005 became a turning point for the regime-opposition dialogue and the efforts for political opening

Despite all these troubles and challenges both came from the ruling elite (Rif’at’s coup attempt in 1983) and the civil society (Hama revolt 1976-1982), Hafez al-Assad managed to remain in power until he died in 2000. What is more, the father Assad ensured that his son Bashar al-Assad would take over his office without flaws.

Bashar al-Assad, Uprising and the Syrian Military: From Reform to Civil War

Bashar al-Assad was 35 when his father Hafez al-Assad died on June 10, 2000; therefore, he was not eligible to rule according to Article 83 of the Syrian Constitution, which required the President of the state to be at least forty years old. Almost immediately, the People’s Assembly voted to change Article 83 and carried Bashar al-Assad to the presidency.41 Bashar al-Assad, taking over his father’s legacy, adopted a political language to which the Syrian people were not accustomed at all, and he promised reforms. In his speech, dated July 17, 2000, Assad said, “we cannot impose the democracy of others on ourselves,” and that Syria will carefully follow a building process on a healthy ground.42

Bashar al-Assad’s critical political reforms and reform promises set the stage for the opposition to overtly voice their political demands. In such an atmosphere, in September 2000, the Syrian opposition published a manifesto calling for the lifting of the state-of-emergency which had been in force since 1963, the release of political prisons, provisions for the freedoms of expression, press and assembly, safeguarding civil rights and liberties, and lifting bans on the exiled to return.

In the manifesto, the opposition underlined that without the implementation of political reforms, none of the economic, social and legal arrangements would be meaningful.43 The most prominent political moves in the implementations of reforms were the closing of the symbolically important Mazza Military prison44 and the release of scores of political prisoners.45 This process, however, did not last long and ended in 2001.

Invasion of Iraq by the U.S. created a pressure on Assad to start the second phase of the negotiations with Syrian opposition. During a football game in March 2004, a fight between Arab and Kurdish fans turned into an insurgence in the neighborhoods heavily populated with Kurds. Dozens died when security sources interrupted the demonstrations in Qamishli.46 Despite the incidents in Qamishli negotiations between the Assad administrations and the opposition was not ended.

The assassination of the Prime Minister of Lebanon, Rafiq Hariri, on February 14, 2005 became a turning point for the regime-opposition dialogue and the efforts for political opening. Along with this development, the process of dialogue was shaped by international dynamics. On October 2, 2004, the United Nations Security Council, with the particular efforts of the U.S. and France, approved resolution number 1559, on the withdrawal of all foreign forces –i.e., Syrian military units– from Lebanon and the disarmament of all organizations –i.e., Hezbollah and the Palestinians living in the Lebanese refugee camps. The Hariri assassination was used as a pretext to put this decision into force.

Syrian troops withdrew from Lebanon on April 26, 2005. With this move, the Assad administration saved itself from the heavy pressures of the international community, and toned down its reform promises. The reform/pressure cycle continued on and off through the end of 2008, and came to an end with the arrests of many opponents. Peoples’ demand for political change spread from Tunisia to other regional countries in late 2010 as demonstrations scaled up in terms of their quality, quantity, aims, demands, methods and discourses, and turned into unprecedented protests in the region.

Demonstrations in Syria turned into mass protests after mid-March of 2011 and the regime retaliated. It is possible to analyze the regime’s response in three main aspects: political co-optation strategy, counter-social mobilization, and the protection of the regime by the army. Assad’s political announcements, his remarks and discourse and reforms as of late January 2012 are part of the political co-optation strategy.

On January 31, 2011, two weeks after Bin Ali was overthrown and left Tunisia, and one week after anti-Mubarak demonstrations matured in Egypt, Assad gave an exclusive interview to the Wall Street Journal, saying that his government stands strong and legitimate. Assad based his legitimacy on his stern attitude against Israel, his support to Palestine via Hezbollah and Hamas, and the development of his country and reforms despite sanctions. He blamed the great powers and their long-lasting involvement in the region for the unrest and anger in the region and said that the discontent about his administration could be eliminated through dialogue.47

On the other side, Assad stressed that people expect change in political, economic and social spheres and that he has worked to meet public expectation since the moment he came to power. As for the situation in Egypt and Tunisia, Assad said that change should be made progressively. He emphasized that reforms in the face of developing incidents in the region would not be effective as they would be reactions, not actions; whereas, actionable and structural reforms require institutional preparation and not only people but also the government should feel ready for them. Syria has a long way to go, otherwise a sudden change would be disaster for them, he stressed.

Understanding the Military’s Action against the Uprising

Assad’s most important argument in the abovementioned interview lays in his remarks denying a power gap in Syria (“there is a difference between having a cause and having a vacuum”).48 Assad’s approach may simply be summarized as: people might have complaints, but it would be impossible to control a rapid change. It was not possible for the people to change the ruling power by force because the nature of the ruling power in Syria did not allow this. Assad underlined that since separation of the ruling elements was not in question, an uprising to change the power would end in a disaster. Forty-five days after this interview, demonstrations began in Syria, although they were disorganized and irresolute in nature. While Assad promised reforms in order to calm down the protests, security forces used brute force against demonstrators, exacerbating the masses.

In the face of these developments, the opposition, who initially had hopes that Assad would keep his promise for reforms and were worried that the demonstrations could lead to a civil war, decided that the Assad regime should be overthrown, so they joined the protests.49 The spread of demonstrations in Syria may be explained by two key factors. The first is that the opposition was encouraged by the toppling of Bin Ali in Tunisia and Hosni Mubarak in Egypt, and the second is the Syrian opposition’s expectation to garner the support of the international community for their anti-Assad protests. One Syrian opponent said that on August 22, an interview with Assad was aired on Syrian TV, but they, instead, stayed up the whole night watching the liberation of Tripoli by the Libyan opposition.50

The army’s ruling power identity in Syria, differently from Egypt, is the number one reason for the army’s protection of the Assad regime

Synchronously Assad administration followed a two-way strategy: The first was the implementation of political inclusion (or co-optation) and persuasion strategies, the Syrian regime organized counter-social mobilization and the second security units had taken action. Hasan Abbas states that Assad had considered that the ruling powers in Tunisia and Egypt were toppled because the protests could not be suppressed, so he set-up a special office to monitor the developments in Syria.51 In the course of events, the demonstrations gradually turned into massive protests –to the contrary of Assad’s expectations expressed in his interview on January 31. In the presence of demonstrations, a power gap did not occur in the regime, as he said, and the army took action to protect the Assad rule.

As a strategy for the longevity of his regime, the organization of a counter-social/sectarian mobilization provided an advantage, yet turned against him. As Hinnebusch puts it, disproportional power in the hands of a social minority keeps the majority disturbed. Although the regime’s cooptation strategy towards the Sunnis alleviated their discomfort somewhat, it is difficult to claim that their concerns were eliminated completely.52 On the other hand, the regime’s hard reaction to the revolts led to radicalization of the resistance, that is, to its taking up arms. Such a sharp dissociation led Alawites to see their survival as being dependent on the longevity of the regime. It was a total war, according to the regime, and if Sunnis win this war, it would be the first step of an ethnic cleansing targeting Alewites.53 In the end, the elites of the regime chose to suppress the upheavals without causing any serious rupture within itself.

Considering the estimated death toll given in a report prepared by an international observer, according to which over a hundred people were killed during the regime’s intervention in the protests,54 it may be said that a security-oriented paradigm against public demands dominated Assad’s two-way strategy. On the other hand, anti-Assad discourses rising from the international community since March pumped up the expectations of the opposition. On March 17, 2011, the Libyan air corridor was declared a No Fly Zone under UN resolution number 1973, and that gave hope to the opposition. A striking example is that towards late 2011, one of the opposition leaders during an interview said, “The [Assad] regime will collapse; it is only a matter of time,”55 and the U.S.56 and Israel issued similar statements.57

Syrian children celebrate the Correctional Movement Anniversary and the recruitment of new Baath Juniors at a school in Aleppo on November 17, 2014. | AFP PHOTO / JOSEPH EID

Syrian children celebrate the Correctional Movement Anniversary and the recruitment of new Baath Juniors at a school in Aleppo on November 17, 2014. | AFP PHOTO / JOSEPH EID

The question at this point is why the army in Syria did not follow in the footsteps of the Egyptian army that sacrificed Mubarak, and chose instead to protect the Assad regime. As mentioned above, the main argument of this study is that the army’s ruling power identity in Syria, differently from Egypt, is the number one reason for the army’s protection of the Assad regime. The President and the army, as the pillars of the regime in Syria, were not in a position to stand apart.

Almost all critical positions were dependent on Assad and the army was even more dependent on him. The command center of the army consisted of persons with unquestionable loyalty to Hafez al-Assad. The blood relatives of Assad or those who were close to Hafez al-Assad, even though they do not have kinship with him –as in the case of Mustafa Tlas– were appointed to these key positions. Although Mustafa Tlas was a Sunni, he served as Syria’s Defense Minister from 1972 to 2004. In addition, Hafez al-Assad had formed individual intelligence units to fend off possible threats from within the army, and so, owing to the loyalty of these units, Hafez al-Assad, even as he was having a heart attack, escaped from his brother Rif’at’s coup.58 Hence, loyalty and patronage were the two determining factors, rather than institutionalization, in the Assad-army relations.59

Bashar al-Assad fell into line with his father after taking his seat in 2000. Looking at the figures in key positions of the army between 2000 and 2011, the Hafez and Bashar al-Assad periods seem quite similar. Indeed, the army became identical with political leadership and the regime through these figures. Although sectarian ties are of a great deal of importance in the longevity of the regime, they are not the only factor. For instance, despite his Sunni origin, Mustafa Tlas remained loyal to the Assad government for 32 years and assumed critical tasks during the process of Bashar al-Assad’s election to the presidency.

Hafez al-Assad, as a former military member, developed a symbiotic relation between the army and the political power during his reign and this relation has continued flawlessly. Known as the power bloc, this special situation has continued during the Bashar al-Assad period as well

Shaped by means of religious sectarian affiliation, family ties and loyalty; the organizational structure of the armed forces were, therefore, transformed into an exclusionary body and –to the contrary of the Egypt’s– remained dependent on the political power. From this angle, having over 70 percent Alawites60 among 200,000 ranking officers and about 300,000 Sunni soldiers is a good indicator of this.

The percentage of Alawites increases to 80 percent among high-ranking officers. Such an organizational structure of the army and its becoming integrated with the political power, as Taylor put, plays as a limited role in the change of the status quo, as such a change is not compatible with the army’s interest.61 In this case, the first priority of the armed forces was to maintain the longevity of the regime and for this purpose, they did not avoid intervening in the protests.

With the impact of all these factors, the uprising turned into a sectarian civil war in 2012. From there on, the issue in Syria was not one of politics but of security. As the army took action, the clashes intensified when international actors’ intervention led to the collapse of institutions in Syria, but the regime had an opportunity to reshape its social ground, lean more on international authoritarian networks, redistribute economic sources, and restructure security forces –the army in particular.62

Conclusion and Some Considerations for the Future of the Syrian Crisis

The Syrian regime, while promising reforms since the onset of the uprising, reacted against the masses. To the contrary of Egypt and Tunisia, the army in Syria became actively involved in the struggle for the survival of the Assad rule. The most important reason for this is the fact that the army and the political power have constituted a power bloc for an historic span of time.

If the Alawite-Sunni polarization, is carried into the army, the army will be distracted from its duty of protecting the country

After Syria’s independence, the power struggle continued among different social segments in the presence of the Minority Politics of the French mandate to dissolve identities, and that caused a period of instability in Syria. Hafez al-Assad used the discharges of army members to his advantage and made a coup in 1970. He remained in power for 30 years, owing to mechanisms different from those of the past.

Hafez al-Assad, as a former military member, developed a symbiotic relation between the army and the political power during his reign and this relation has continued flawlessly. Known as the power bloc, this special situation has continued during the Bashar al-Assad period as well, despite promises and implementations for reforms during his early days in power. On account of this sui generis form of Assad rule, the upheavals starting in 2011 did not fracture the political bloc. The uprisings in Syria remained less heterogeneous compared to Egypt’s and were smaller in scale.

The protests in Syria signaled a demand for change despite many ambiguities, considering their ratio to the total population, their organization, political demands, their rapid spreading countrywide, Assad’s initial reactions, and the political atmosphere these events created in the region. Let alone, in terms of this study’s argument, the quantity of masses did not play determining roles.

In a way, with the army’s intervention against the masses, the power struggle in Syria has returned to old patterns. The most important difference of the existing power struggle from those in the past was that it has turned into “a proxy war,” with the interventions of regional and global forces. These interventions not only escalated the Syrian uprising into a civil war but also led it to transform into an international crisis and an acute deadlock.

The question about how the security units and the army in particular will be reshaped is one of the most critical issues in the resolution of the Syrian crisis. When the current state of affairs and the future of the civil war in Syria are considered, it may be said that four factors will play an effective role in reshaping the army and structuring army-politics relations: (1) The number of terror organizations and armed groups increases as the crisis deepens. (2) the break-outs occur in the army, (3) the de facto support of Iran and Hezbollah, and (4) Russia’s involvement in the Syrian civil war.

The process which started with the armament of opposition groups in the face of the Syrian regime’s intervention in the demonstrations has led to the emergence of many organized armed groups. In the early periods of the crisis, the Free Syrian Army (FSA) with international support assumed various tasks. The FSA was expected to organize and control fighters and groups in order to topple the regime and to become a primary part of restructuring the army after Assad.

As the civil war has intensified and evolved into a proxy war by international actors, not only has the FSA become dysfunctional but also countless numbers of armed groups have emerged. Most of the terror organizations –the YPG, DAESH, and Nusrat in particular– have become part of the proxy war and have played a critical role in keeping the crisis unresolved. If the Syrian crisis is resolved, the extradition of terror organizations and the integration of the future armed-units against the regime are major problems as far as the future of the Syrian issue is concerned.

A large number of defections from the military have involved Sunni soldiers, which means that the lower ranks in the army will consist of Alawites. More importantly, such homogenization will create security reflexes among military members with sectarian tendencies. If the Alawite-Sunni polarization, which has deepened through both the suppression and inclusion mechanisms for long years, is carried into the army, the army will be distracted from its duty of protecting the country. In order for such a scenario not to occur, the post-crisis administration should professionally structure the army and take all necessary measures to keep sectarian polarization at the lowest level.

Shortly after the onset of the demonstrations in Syria, Iran and Hezbollah provided support for the Assad regime and that intensified sectarian reflexes. Iran and Hezbollah’s support to Assad cannot be justified by only sectarian reasons; Iran’s wish for an opportunity to reach Lebanon via Syria and the Assad regime’s support for Hezbollah against Israel are other reasons beyond sectarian tendencies. However, any factor in any dimension may easily create unintentional consequences and the Syrian civil war remains as an international, political and social crisis. For this reason, even if Iran and Hezbollah strategically rationalize their support to Assad, that support is easily perceived as sectarian solidarity in its social aspects. In this case, sectarian polarization inevitably becomes an international issue.

Russia, as well, has supported the Assad regime since the onset of the Syrian crisis. In the early days of the crisis, Russia exhibited its support by vetoing a UN Security Council resolution against Assad. Since late 2015, Russia’s support has transformed into a de facto intervention. Russian airstrikes against almost all of the opposition groups under the pretext of the “war against terror” as of October 2015 in particular was a critical move to secure Assad’s continuing power. Russia’s move is also critical in terms of restructuring the Syrian army. Russian military bases in Syria, the weapons technology Russia transferred to Syria and the deployment of S300 missiles, as one of the most state-of-the-art weapons of the Russian defense technology, are critical for the future of Syria. Considering all of this, Syria will obviously be quite dependent on Russia.

In conclusion, the intensified sectarian polarization with the departures from the army as the crisis has intensified, the support of Iran and Hezbollah and Russia’s intervention in Syria are the new and effective parameters in deepening of the crisis and the restructuring of the army. If the Assad rule continues over a prolonged period, a more sensitive, more authoritarian and more sectarian army structure will undoubtedly be formed against “internal threats” for the sake of protecting the regime rather than the country.

Endnotes

- Milan Svolik, “Power Sharing and Leadership Dynamics in Authoritarian Regimes,” American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 53, No. 2, April 2009, pp. 477 – 478.

- William C. Taylor, Military Responses to the Arab Uprising and the Future of Civil Military Relations, (New York: Palgrave, 2014), p. 23.

- Edward Luttwak, Coup d’État: A Practical Handbook, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1969), p. 12.

- Eliezer Be’eri, “The Waning of the Military Coup in Arab Politics,” Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 18, No. 1 (January 1982), pp. 71-72.

- Peter D. Feaver, “The Civil-Military Problematique: Huntington, Janowitz and the Question of Civilian Control,” Armed Forces and Society, Vol. 23, No. 2 (Winter 1996), pp. 151-152.

- Jonathan M. Powell and Clayton L. Thyne, “Global Instances of Coups from 1950 to 2010: A New Dataset,” Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 48, No. 2 (2011), p. 255.

- Be’eri, “The Waning of the Military Coup in Arab Politics,” p. 78.

- Jason Brownlee, “…And Yet They Persist: Explaining Survival and Transition in Neopatrimonial Regimes,” Studies in Comparative International Development, Vol. 37, No. 3 (Fall 2002), p. 42.

- Steven Cook, Yönetmeden Hükmeden Ordular, (Türkiye, Mısır and Cezayir: 2008), p. 27.

- Eva Bellin, “Reconsidering the Robustness of Authoritarianism in the Middle East, Lessons from the Arab Spring,” Comparative Politics, Vol. 44, No. 2 (January 2012), pp. 129-134.

- Bassam Haddad, “Why Syria Is Not Next . . . so far,” Jadaliyya, (09 March 2011), retrieved from http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/844/why-syria-is-not-next-.-.-.-so-far_with-arabic-tra.

- The Charter of the League of Nations, Article 22, Clause 4, retrieved from http://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/leagcov.asp.

- Stephen Longrigg, Syria and Lebanon under the French Mandate, (London: Oxford University Press, 1958), p. 158; Eliezer Be’eri, Army Officers in Arab Politics and Society, (New York, Praeger, 1970), p. 97.

- Patrick Seale, Assad of Syria: The Struggle for the Middle East, (Berkley: University of California Press, 1988), p. 37.

- Philip Khoury, Syria and French Mandate: The Politics of Arab Nationalism, 1920-1945, (Princeton: Princeton University Press), pp.170-172.

- Bou-Nacklie, “Les Troupes Speciales: Religious and Ethnic Recruitment, 1916-46,” International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 25, No. 4, (November 1993), pp. 650-652.

- Alford Carleton, “The Syrian Coups d’Etat of 1949,” Middle East Journal, Vol. 4, No. 1 (1950), p. 2.

- John Galvani, Syria and the Ba’ath Party, MERIP Reports, No. 25, (February, 1974), pp. 5-6.

- Hanna Batatu, “Some Observations on the Social Roots of Syria’s Ruling, Military Group and the Causes for its Dominance,” Middle East Journal, Vol. 35, No. 3 (Summer 1981), p. 340.

- Nikolaos Van Dam, Suriye’de İktidar Mücadelesi: Esad ve Baas Partisi Yönetiminde Siyaset ve Toplum, Translation: Aslı Falay Çalkıvık and Semih İdiz, (İstanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2000), p. 59.

- Daniel Pipes, “The Alawi Capture of Power in Syria,” Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 25, No. 4, (October 1989), p. 441.

- Itamar Rabinovich, Syria under Ba’th 1963-1966: The Army Party Symbiosis, (Jerusalem, Israel: University Press, 1972).

- Mahmud A. Faksh, “The Alawi Community of Syria: A New Dominant Political Force,” Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 20 No. 2 (April 1984), p. 144.

- Batatu, “Some Observations on the Social Roots of Syria’s Ruling, Military Group and the Causes for its Dominance,” p. 343.

- Eyal Zisser, “The Syrian Army on Domestic and External Fronts,” in Barry Rubin and Thomas Keaney (eds.), Armed Forces in the Middle East Politics: Politics and Strategy, (London, Routledge, 2001), p. 120.

- Van Dam, Suriye’de İktidar Mücadelesi, p. 115; Batatu, “Some Observations on the Social Roots of Syria’s Ruling, Military Group and the Causes for its Dominance,” p. 332.

- Kirk S. Campbell, Civil-Military Relations and Political Liberalization: A Comparative Study of the Military’s Corporateness and Political Values in Egypt, Syria, Turkey, and Pakistan, Unpublished PhD dissertation George Washington University, Columbian College of Arts and Sciences, (2009), p. 229.

- Hicham Bou Nassif, “Generals and Autocrats: Coup-Proofing and Military Elite’s Behavior in the 2011 Arab Spring,” Unpublished dissertation thesis, Department of Political Science, Indiana University, p. 181.

- Joseph Holliday, “The Syrian Army Doctriner Order of Battle,” Institute for Study of War, 2013, p. 7.

- Campbell, Civil-Military Relations, and Political Liberalization: A Comparative Study of the Military’s Corporateness and Political Values in Egypt, Syria, Turkey, and Pakistan, p. 228.

- Nassif, “Generals and Autocrats: Coup-Proofing and Military Elite’s Behavior in the 2011 Arab Spring,” p. 181.

- Alasdair Drysdale, “The Succession Question in Syria,” Middle East Journal, Vol. 39, No. 2 (Spring 1985), p. 248.

- Holliday, “The Syrian Army Doctriner Order of Battle,” p. 8.

- For the names of these units, see: Nassif, “Generals and Autocrats: Coup-Proofing and Military Elite’s Behavior in the 2011 Arab Spring,” p. 182.

- Zisser, “The Syrian Army on Domestic and External Fronts,”; Pipes, “The Alawi Capture of Power in Syria.”

- Nikolaos van Dam, “Middle Eastern Political Cliches: “Takriti” and “Sunni Rule” in Iraq; “Alawi Rule” in Syria”: A Critical Appraisal,” Orient, Vol. 21, No. 1 (January 1980), pp. 42-

- James T. Quinlivan, “Coup-proufing, Its Practice and Consequences in the Middle East,” International Security, Vol. 24, No. 2 (Autumn, 1999).

- Be’eri, “The Waning of the Military Coup in Arab Politics,” p. 78.

- Risa Brooks, Political-Military Relations and the Stability of the Arab Regimes, (New York, Oxford University Press, 1998), p. 26.

- Middle East Watch, Syria Unmasked: The Suppression of Human Rights by the Assad Regime, (New Haven, Yale University Press, 1991), pp. 39-40.

- For all related decisions, see: “The Syrian Parliament Amends Article over the Age of Syrian President,” retrieved 15 January 2015 from www.presidentassad.net.

- “President Assad 2000 Inauguration Speech,” (17 July 2000), retrieved 17 January from www.presidentassad.net.

- “The Statement of 99,” SETA, 15 January 2016, retrieved from http://www.setav.org/public/indir.aspx?yol=%2fups%2fdosya%2f80173.docx&baslik=Syria+-+The+statement+of+99+and+statement+of+1%2c000.

- “Amnesty International Welcomes the Release of Political Prisoners,” (16 November 2000), retrieved from www.amnesty.org.

- Joshua Landis and Joe Pace, “The Syrian Opposition,” The Washington Quarterly, Vol. 30, No. 1, (2006-2007), p. 47.

- Gary C. Gambill, “The Kurdish Reawakening in Syria,” Middle East Intelligence Bulletin, Vol. 6, No. 4, (April 2004).

- “Interview with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad,” Wall Street Journal, 31 January 2011, retrieved from http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748703833204576114712441122894.

- “Interview with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad,” Wall Street Journal, 31 January 2011, retrieved from http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748703833204576114712441122894.

- Ufuk Ulutaş, “The Syrian Opposition in the Making: Capabilities and Limits,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 13 No. 3 (2011), pp. 98-101.

- Abdur Rahman al-Shami, “Syrians Must Contemplate Foreign Help - if not the West’s,” The Guardian, (31 July 2011), retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2011/aug/31/bashar-assad-must-be-stopped

- Hassan Abbas, “The Dynamics of the Uprising in Syria,” Arab Reform Brief, No. 51, October 2011, p. 2.

- Raymond Hinnebusch, “Authoritarian Resilience and the Arab Uprising: Syria in Comparative Perspective,” Ortadoğu Etütleri, Vol. 7, No. 1 (July 2015), p. 24.

- Emile Hokayem, Syrias’s Uprising and the Fracturing of the Levant, (London: Routledge, 2013), pp. 52-53.

- “Syrian Authorities Urged to Lift Repressive Laws amid Violence,” Amnesty International, (28 March 2011), retrieved from http://www.amnestyusa.org/news/press-releases/syria-amnesty-international-

urges-syrian-authorities-to-lift-repressive-laws-amid-violence. - “Bashar al-Assad Is Mentally Unbalanced - Syrian Muslim Brotherhood Chief,” Al-Sharq Al-Awsat,

(05 December 2011), retrieved from http://english.aawsat.com/2011/12/article55244117/bashar-al-

assad-is-mentally-unbalanced-syrian-muslim-brotherhood-chief. - Macon Philips, “President Obama: “The Future of Syria Must be Determined by its People, but President Bashar al-Assad is Standing in Their Way,” (18 July 2011), retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/2011/08/18/president-obama-future-syria-must-be-determined-its-people-president-bashar-al-assad.

- Joshua Landis, “The Syrian Uprising of 2011: Why the Assad Regime is Likely to Survive to 2013,” Middle East Policy Council, Spring 2012, Vol. 19, No. 1, p. 73. See a similar statement issued by Turkish Foreign Minister in August 2012: “Davutoğlu Esad’a Ömür Biçti,” NTV, (24 July 2012), retrieved from http://www.ntv.com.tr/turkiye/davutoglu-esada-omur-bicti,Nsez_e7zmEO7uz5O9Pv6hw.

- Van Dam, Suriye’de İktidar Mücadelesi: Esad ve Baas Partisi Yönetiminde Siyaset ve Toplum, pp. 122-124.

- Defense Ministers of the Bashar al-Assad period were of the following sectarian origin: Fahd al-Freij, a Sunni; Daoud Rajha, a Christian; Ali Habib, an Alawite; Hasan Türkmani and Mustafa Talas, both Sunnis. The Chiefs of General Staff were Ali Ayyoub, an Alawite; Daoud Rajha, a Christian; Fajd Jassem; Hasan Türkmani; and Hikmat Shehabi, all three Sunnis. All military and civil intelligence directors consisted of Alawite military officers. For details see: Nassif, “Generals and Autocrats: Coup-Proofing and Military Elite’s Behavior in the 2011 Arab Spring,” pp. 177-182.

- Reva Bhalla, “Making Sense of the Syrian Crisis,” Stratfor, (May 5, 2011).

- Taylor, Military Responses to the Arab Uprising and the Future of Civil-Military Relations in the Middle East: Analysis from Egypt, Tunisia, Libya and Syria, pp. 102-103.

- Steven Heydemann, “Syria and the Future of Authoritarianism,” Journal of Democracy, October 2013, Vol. 24, No. 4, pp. 60-61.