Introduction

Muslims constitute almost ten percent of the Russian population today. The Muslim population lives in different regions of Russia, speaking different languages and representing diversified socio-political dynamics. For instance, Tatarstan, located in the middle of the Russian Federation, has just over fifty percent Turkic-Muslim population; whereas the Chechen Republic located in the southernmost flank of Russia has over ninety percent Chechen-Muslim population. In addition, Russia’s metropoles are home to millions of Muslims who have migrated from the Muslim regions of Russia and from the post-Soviet countries. Russia also shares borders with multiple Muslim majority countries and often engages in dialogue with several Muslim communities in different regions.

Islam is not a novel phenomenon for Russia. The Russian history is deeply intertwined with the histories of Muslim communities that have lived inside and around the territories of today’s Russia. The Russians have had periods of conflict, competition, subjugation and cooperation with Muslims located inside and outside of Russia. The deep roots of Islam in Russia make the image of Islam and Muslims in Russia both complex and specific. I argue that the image of Islam in Russia impacts the way the nation deals with Muslim communities. Russia produces diversified narratives of Islam and these narratives have the potential to be used to politicize or securitize at least a portion of Muslims. This work examines three primary narratives on Islam that stem from diversified roots.

Russia produces diversified narratives of Islam and these narratives have the potential to be used to politicize or securitize at least a portion of Muslims

The first narrative stems from the period when Orthodox Russians were subjugated by the Golden Horde, whose rulers converted to Islam in the 14th century. The rule of Golden Horde is still remembered as the Tatar yoke in modern Russian historiography. Such narrative impacts the way Russia considers Muslims, especially communities in the Volga region, and creates tension between today’s Russian Federation and the Republic of Tatarstan.

The second narrative stems, from the period when the Russian Empire expanded becoming a heterogeneous Empire, with a significant Muslim population. From the mid-18th century, the Russian Empress Catherine II1 attempted to employ a portion of Muslim ulama2 in order to integrate Muslim communities into the imperial structure. The Muslim population who were connected to the Empire through religious channels would be deemed trustworthy while others who follow different paths would be punished. The tradition of cultivating a trustworthy Muslim religious caste would survive the Soviet Union. Today, the Russian state still maintains ties with certain religious figures in different Muslim regions.

The third narrative stems from the openness of Russia to the Western influence. In the early 18th century, Peter the Great embarked on his modernization project, through which he introduced Western technology and customs to Russia. This was the beginning of a long period of ambivalent relations with the West. On the one hand, Russia aspired to become a European power by adopting European-style reforms and becoming more engaged with European politics. Europe, on the other hand, has never readily accepted Russia to the club but has readily exported a European way of life. The image of Muslims in Russia has not been independent from the Western influence as well. As a result, the image of Islam in the West has influenced the image of Islam in Russia on multiple occasions.

To examine the security narratives of Islam in Russia, I use a social constructivist framework and benefit from the premises of securitization theory. A social constructivist framework enables us to examine the practical consequences of the image of Islam in Russia. The securitization theory helps examine how Islam is considered a threat to not only the Russian state, but also Russian civilization and state sovereignty. Using securitization theory, I identify the way Islam is coded in the Russian psyche and the threat Muslims were supposed to pose to state, sovereignty and civilization.

The aim of this work is threefold: first, to assess to what extent memory created by the historical shifts in power dynamics between the Russian rule and the Muslim population influences the national securitization language vis-à-vis Islam; secondly, to examine how Russia’s securitization language vis-à-vis Islam differentiates from that of the West; and, last but not least, to analyze the properties of Russia’s securitization narrative towards Islam.

Theoretical Framework

This work benefits from the securitization theory and uses a social constructivist framework. I examine how Russia sees Islam and how Russia’s narrative on Islam enables extraordinary measures against Muslim communities by the Russian state. Social constructivism helps to analyze the impact of Russia’s perception of Islam on its dealings with Muslim communities. Securitization theory helps understand and explore how these narratives can be politicized and securitized.

Social Constructivism

Social constructivism sees the social world as one of our own making and considers language as the most important way to making the world what it is.3 Constructivism was first conceptualized in 1989 by Nicholas Onuf, in World of Our Making, where the author argued that the phenomenon of international relations depends on how we think about it.4 The framework was popularized by Alexander Wendt, a leading figure in constructivist theory in international relations discipline. Wendt used the famous statement ‘anarchy is what states make of it’ as the title of his oft-cited article and employed constructivism to build a bridge between rationalist-reflectivist and realist-liberal debates in the international relations discipline, promoting constructivism as via media.5 It is important to note that Wendt has thoroughly benefited from Anthony Giddens’ structuration theory.6 With reference to Giddens’ structuration theory, Wendt challenged the structural approaches of Alexander Waltz and Immanuel Wallerstein in International Relations discipline.7 He proposed an approach that takes social structures into consideration in analyzing the affairs of international politics.8

Social constructivism underlines the role of agents in constructing structures. Agents are human or non-human entities that act on behalf of human beings within the framework of the role attributed to them. Institutions are constructed by these agents who act in accordance with their presence and construct institutions by acting on them. Rules constitute an important part of the interaction between agent and structure by making the process of interaction continuous and repetitive. Rules gain function through agents who abide by them.9 According to Onuf, rules play both constitutive and regulative role in this process of interaction.10 To sum up, per social constructivism, agents and institutions interact in a social construction within the framework of certain rules that govern these interactions.

The handout shows one of the largest mosques in Russia, Kul Sharif Mosque located in Kazan, Republic of Tatarstan. / SHUTTERSTOCK

The handout shows one of the largest mosques in Russia, Kul Sharif Mosque located in Kazan, Republic of Tatarstan. / SHUTTERSTOCK

This framework helps understand and explain how societies make people and how people make societies, as well as the roles of rules and institutions in this process. Although it is not originally an international relations theory, social constructivism gained significant popularity in this discipline. Security is one of the areas where the framework was used to explain the way certain issues become the matters of security and addressed accordingly.

Securitization Theory

Securitization theory attempts to explore what quality makes something a security issue and what do terms ‘existential threat’ and ‘emergency measures’ mean.11 The concept of securitization was first used by Ole Wæver in 199512 and further developed in 1998 by Barry Buzan, Ole Wæver and Jaap De Wilde in a book titled as Security: A New Framework of Analysis. As presented by Buzan and Wæver, securitization theory uses a constructivist framework.13

The Russian victory against the Muslims of Volga region in 1552 shifted the balance of power in favor of Russia, against the Kazan, Crimean, Astrakhan, Sibir Khanates and Nogay horde

Securitization can be defined as the practice of framing an issue as something beyond politics or above politics. According to securitization theory, an issue can be classified in a spectrum ranging from non-politicized (handled within the framework of established rules of the game) through politicized (requiring governmental action) to securitized (constituting existential threat to a certain referent object).14

There are three units in securitization theory: referent object, securitizing actors and functional actors. Referent objects are things that are claimed to be existentially threatened and have a legitimate claim to survival. Traditionally, states are considered as referent objects in international relations theory. Securitization theory enables the examination of not only the military threats but also economic, political and societal security threats to not only states but also societies, governments and other forms of real or imagined communities.15 Securitizing actors are the ones who securitize certain issues by declaring that a referent object is existentially threatened. A president, king or an opinion leader can act as securitizing actor. Functional actors are neither referent objects nor securitizing actors but they significantly influence decisions in the field of security.16

Securitization theory assumes that naming something as ‘security issue’ constitutes the first step towards securitization. That is, security issues are securitized through linguistic exercises that legitimize extraordinary measures against certain issues. Here, it is important to note that securitization theory interacts with speech-act theory.17 According to the speech-act theory, saying is a commitment that brings about action, as in betting or promising. In this vein, when a statesman utters the word ‘security,’ he/she commits himself to take extraordinary measures against a threat.18 Securitization is a linguistic practice that aims to convince a certain audience to accept that an issue is threatening enough to deserve an immediate extraordinary measure.19 Therefore, inasmuch as the units listed above, the target audience also plays an important role in the process of securitization.

By employing securitization theory and a social constructivist framework, this article examines the way Islam is perceived to be a security issue for Russia. I examine how Islam is presented as a non-military threat to various referent objects by Russia and how these processes affect policy making. Securitization theory enables the examination of cases where securitizing actors may construct objects other than states as referent object. This approach helps distinguish between the ways Islam is securitized in terms of the referent object it threatens. Securitization theory does not rule out the possibility of an overlay of an external actor to a security complex as well.20 This work benefits from this premise in assessing how the Western narrative influences Russia’s securitization narrative of Islam.

History of Islam in Russia

This study claims that Russia’s security narratives are historically rooted. Russia’s past encounters with Muslims have a significant impact upon the way Russia constructs security narratives around Islam. Thus, before moving on to examine Russia’s security narratives on Islam, I provide a brief historical background of Islam in Russia.

Islam made its first inroads into the Caucasus in the 7th century with the arrival of Arab merchants. By the 10th century, Islam was entrenched as demonstrated by Volga Bolgar Khanate’s declaring Islam to be the state religion. The first serious encounter between the Russians and the Muslims took place following the rapid expansion of Chingizid Empire. Kievan Rus’, the predecessor to the Russian Empire, was invaded by the Chingizid Army in 1237. Subsequently, Russia’s Mongol rulers declared Islam as the state religion in the 14th century. During two hundred years of subsequent Mongol rule over the Slavic principalities, the Russian principalities were governed under a central authority through a complicated taxation, fiscal and communication system, laying the groundwork for the subsequent Russian Empire.

For centuries, Islamic civilization developed in the east of Moscow, primarily around the upper Volga region, prior to the expansion of Muscovy in the 16th century. The Mongol invasion of the Rus’ was followed by the dominance of Turkic-Muslim khanates over the Slavic principalities, a period that would be remembered as the ‘Tatar yoke.’21 This exercise of remembering a period with charged language –that makes an ethnic distinction– has played a significant role in defining the image of Muslims in the minds of Russians.

The Russian victory against the Muslims of Volga region in 1552 shifted the balance of power in favor of Russia, against the Kazan, Crimean, Astrakhan, Sibir Khanates and Nogay horde.22 The invasion of Kazan in 1552 made Islam a domestic issue with the inclusion of significant Muslim-inhabited regions into the Russian state. Russia initially attempted to deal with this issue with forcible conversion, massacre and relocation of communities. 23 When this proved counterproductive, Russia sought to resolve the issue through an imperial divide-and-rule policy. The foundation of Orenburg Spiritual Board24 under Catherine II transformed Russia’s relations with its Muslim subjects. Accordingly, Islam would be deemed harmless and helpful to the state as long as it was practiced under the patronage of the said state. It is noteworthy that Catherine’s aim to market her rule in the West as an enlightened one has affected this move.

The presence of Ottoman Empire as the khalifate that pledged to protect Muslims at its frontiers made members of this community appear more threatening for the Russians.25 This factor pushed Russia to provide a solution to religious heterogeneity within the Empire. From the 18th century on, after observing the failure of oppressive policies, Russia’s treatment of Muslims relented. As such the Russian imperial bureaucracy cooperated with a portion of Muslim ulama to strengthen the bonds between the Empire and its Muslim subjects. This process of collaboration between the Muslim ulama and the Russian state culminated in the foundation of a loyal ecclesiastical structure of Islamic faith. The Orenburg Spiritual Board, founded in 1788 within the framework of this new policy approach of Catherine II, securitized the Muslim who did not practice their religious belief within the framework of the official imperial line.

The Soviet Union had its own securitization narrative vis-à-vis Muslims based on Marxist principles. However, a policy conducted under the guidance of the exclusivist nature of the Marxist doctrine, which considered religion to be the ‘opium of the people,’ would antagonize the Muslims

The Soviet Union had its own securitization narrative vis-à-vis Muslims based on Marxist principles. However, a policy conducted under the guidance of the exclusivist nature of the Marxist doctrine, which considered religion to be the ‘opium of the people,’26 would antagonize the Muslims. The Bolsheviks were aware of this and acted accordingly. Following the October Revolution, the Bolsheviks issued the ‘Declaration of Rights of the Peoples of Russia’ in which they guaranteed nationalities’ self-determination demands.27 In December 1917, the Bolsheviks issued another declaration that directly addressed the Muslim communities as: “All you, feel free to live according to your religious beliefs, your national and cultural institutions are independent and inviolable.”28 By the mid-1920s a relentless campaign against Muslims along with all religions ensued. Thus, by 1930, the waqf29 institutions were swept away,30 more than 10,000 of the 12,000 mosques were closed and over 90 percent of Muslim clergy were banned from performing their duties.31

Despite the Soviet antagonism against all forms of religion, the Soviet state supported the expansion of the reach of the official Muslim institutions in exchange for a call to arms against Nazi Germany.32 This was a significant and critical juncture enabling the Soviet Union to adopt a similar securitization narrative towards Islam with its predecessor Russian Empire. For decades, official Islamic activity could function while any kind of religious activity outside of the official boundaries was subject to punishment and labeled as charlatanism.33

The official grip over religious institutions relented following the demise of the USSR. However, the habit of employing official ulama figures and excluding other Islamic activities survived. Today, there are numerous Muslim religious institutions that continue to play a significant role in religious life across Russia. While current laws do not monopolize state authority over Islamic institutions, there are several limitations the Islamic institutions face to secure their loyalty to the state structure. These institutions play a significant role in maintaining the loyalty of the Muslim communities to the state. In the case of Chechnya and the Crimea, the Kremlin has effectively collaborated with religious authorities to suppress dissentious Muslims.

While current laws do not monopolize state authority over Islamic institutions, there are several limitations the Islamic institutions face to secure their loyalty to the state structure

One can spot certain continuities in Russia’s dealings with its Muslim question. First, the religious difference between the Slavic Orthodox and the Muslim communities has been a defining factor in relations between the Russian state and the communities. More than ethnicity, language and national identity, religious identity impacted the way Muslim communities are treated. Secondly, following the establishment of a Russian state structure, we can observe a tendency to develop a loyal ecclesiastical Muslim community and benefit from them to establish control over the wider community. The Islamic activities and personalities that fall outside of this official lineage have been subject to securitization.

Components of Russia’s Securitization of Islam

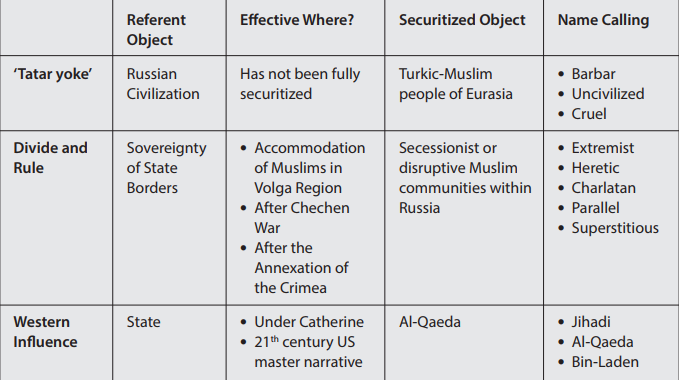

In this part, I examine three salient dynamics in Russia’s securitization of Islam. The first way to securitize Islam has been in the form of seeing Islam as an uncivilized Eastern savagery. The roots of this narrative can be found in the psychological effect of the domination of the Golden Horde over the Slavic principalities across Eurasia. This narrative had an impact on Russia’s imagination of the Muslim peoples of the east of Volga Region. A second narrative stems from the idea of distinguishing within Muslims through institutional arrangements to secure the loyalty of at least a portion of the Muslim population. The Muslims who did not conform to the official boundaries have been called heretical and been subject to judicial procedure. A third narrative stems from the Western influence on Russia.

Russian mogul Kerimov, Mayor of Moscow Sobyanin, Turkey’s President Erdoğan, Russian President Putin, Grand Mufti of Russia Gaynetdin, and Palestinian President Abbas attend the opening ceremony of the Moscow Central Mosque on September 23, 2015. | TURKISH PRESIDENCY / YASİN BULBUL

Russian mogul Kerimov, Mayor of Moscow Sobyanin, Turkey’s President Erdoğan, Russian President Putin, Grand Mufti of Russia Gaynetdin, and Palestinian President Abbas attend the opening ceremony of the Moscow Central Mosque on September 23, 2015. | TURKISH PRESIDENCY / YASİN BULBUL

Impact of Russian Historiography on the Golden Horde of the Russian Narrative on Muslims

Aside from the real impact of the Golden Horde on Russian state tradition, the imprint of ‘Tatar’ rule was by no means positive in the Russian psyche. The popular discourse regarding the rule of the Golden Horde suggests that it prevented the Russians from benefitting from the European enlightenment, pioneered a traditional Oriental despotism in Russia and exploited Russia to the point of leaving it permanently backwards.34 This narrative is used to identify a threat that is against Russian statehood as well as the civilization that accompanies it. The ‘Tatar yoke’ has been part of Russian historiography and narrates how the Golden Horde ruthlessly demolished the Byzantine-inspired Russian Orthodox civilization and replaced it with a highly centralized and totalitarian regime.

The formative narratives of Russian history, as constructed by scholars like Tatischev, Karamzin and Solov’ev, relied heavily upon the old chronicles, which examined the Golden Horde from a religious perspective and saw the rulers as Tatar infidels who sought to harm good Christians.35 As late as the end of the 19th century, Russian intellectuals were fearful of a new Tatar yoke expressing the belief that Mongols would cooperate with the Chinese and enslave Russia.36 The Russian elite’s conceptualization of the Tatar yoke remained almost unchanged until the Soviet era, when state identity underwent a fundamental transformation.37 In August 1944, when historical Tatar hero Idegei appeared in a newspaper article, the Central Committee of the Communist Party, after heated discussions, ruled that the article was anti-Russian thereby put an end to all positive narratives on Tatar-Mongol leaders.38 Under the Soviet Union, the narrative on the Golden Horde and the history of Tatars remained antagonistic.

The accusations of heresy, fanaticism, banditry and terrorism are used to supplement the extraordinary security measures by state apparatuses on various groups of Muslims who fall outside of the political aims of the ruling party

Following the demise of the USSR, Yeltsin’s education policy aimed to dismantle the one-sided centralized communist ideology from textbooks. This attempt brought about a fragmentation of historical discourse. In 2003, it was brought to Putin’s attention that a textbook, recommended by the Ministry of Education, stated Putin’s Presidency was the result of a coup d’etat arguing that he was constructing a police state. Following this incident, Putin met with historians and academicians at Lenin Library and suggested the history should not be discussed on political grounds and emphasized one’s feelings of pride about the nation’s past.39 This incident paved the way for closer government control over textbooks and increased uniformity of historiography.

When the Republic of Tatarstan achieved partial sovereignty under the Russian Federation in the mid-1990s, the discourse became controversial as the nationals of this almost sovereign republic are called as Tatars as well.40 Consequently, Tatar scholars began to challenge the Russian historiography that represented Muslim Tatars antagonistically. While the Tatar historians are divided internally as to how to re-evaluate the period of Golden Horde, they all challenge the discourse of the Tatar yoke. The majority of Tatar historians adopted a position that maintains the Golden Horde has contributed to the modernization of not only the Tatars but also Russians. They have also downplayed the influence of the Mongol aristocracy and emphasized the Turkic identity of the Golden Horde.41 Another group of Tatar historians emphasized the Tatars’ Bulghar identity, which dates to the 10th century Bulghar Khanate. They accepted the cruelties of the Golden Horde and attempted to dissociate today’s Tatars from the Golden Horde. 42 Although Tatar scholars could not realize a revision of the era of Golden Horde in history textbooks through the Ministry of Education, they made significant progress by negotiating with multiple Russian publishing houses which accepted revisions in their history textbooks in order to get a share from Tatarstan’s textbook purchases.43

It can be argued this narrative has not been fully securitized by a Russian authoritative voice. However, the discourse revolving around the heritage of two centuries of Turkic-Muslim rule over Russia has been highly politicized on multiple occasions. Tatarstan’s effort to renew the image of Tatar identity through pursuing revision in dominant historiography and Russia’s ensuing uniformity in history textbooks could be considered within the framework of politicization. The employment of this collective memory within a securitization narrative is contingent upon the tensions between Russia and the Muslims of Volga region. A shift in power relations between the Russian center and Muslim periphery in Volga region can bring about the strengthening of this securitization narrative in the future.

Russia’s Use of the Imperial Policy of Divide and Rule to Securitize Disloyal Muslims

Following the foundation of Orenburg Spiritual Board, the Russian state could incorporate a portion of Muslims into the Imperial structure. Subsequently, the Russian state adopted a habit of considering Muslims that are incorporated through the official channels as trustworthy. The Muslims and the ulama figures who act outside of the officially mandated structure have been called as heretic and punished.

Towards the end of 19th century a religious figure named Bagautdin Vaisov pioneered a revisionist movement against the Orenburg Spiritual Board. The officially sanctioned Muslim ulama prevented Vaisov from gaining real ground with the help of the imperial state authorities. Eventually, the local police in Kazan stormed the building where the followers of Vaisov were barricaded themselves, killing several in the group.44 This incident demonstrates the nature of cooperation between the imperial authorities and the officially sanctioned ulama.

The Soviet Union adopted a tough stance towards any manifestation of religion but eventually adopted a similar securitization narrative during the WWII. Under the Soviet Union, the so-called ‘parallel Islam’ referred to the Sufi Muslim networks that developed on illegal platforms and were often brutally suppressed by the state apparatuses.45 For their part, the official institutions promulgated fatwas46 designed to delegitimize the activities of Sufi orders with the help of a linguistic exercise labeling such activities as “charlatanism” and “fanaticism,” and spreading superstition as well.47

More recently, the Russian Federation adopted a similar stance towards Islamic activities under its domain. The accusations of heresy, fanaticism, banditry and terrorism are used to supplement the extraordinary security measures by state apparatuses on various groups of Muslims who fall outside of the political aims of the ruling party. For instance, Putin has committed to solve the Chechen conflict by eliminating ‘radical Islam’ through protecting and restoring ‘traditional’ Islam. In June 2002, Putin would declare that ‘not all’ Chechens are terrorists.48 Putin further solidified his policy approach by co-opting the former Mufti of the Chechen resistance, Ahmad Kadyrov. Following Ahmad’s murder, Ramzan Kadyrov replaced his father as the head of the Chechen Republic. It is ironic that Ramzan Kadyrov, prone to sharing his extravagant lifestyle with his followers on social media49 and infamous for the human rights records in his statelet,50 fits the image of the leaders of the Chechen resistance. Russia’s securitization narrative that targets figures remaining outside of the official structure can provide an explanation to this dilemma.

The generic image of Chechen fighters during the first Chechen War, as evident in their description in the news, was largely a group of cruel bandits terrorizing the region

The process following Russia’s annexation of the Crimean Peninsula from Ukraine was another manifestation of this securitization narrative. This time, Russia acted quicker than it did in the Chechen case in dividing friends and enemies within the Crimean Tatar community. With the help of Ravil Gainutdin, the head of one of the most influential religious organizations, Russian Council of Muftiates, Russia would soften the stance of the Crimean Tatar Mufti Emirali Ablayev against the Russian occupation.51 On the other hand, the sovereign elected body of the Crimean Tatar Meclis,52 which opposed the annexation of Russia was labeled as ‘extremist’ and persecuted. Because of this securitization, influential members of Meclis were barred from entering the peninsula and their activities forcibly terminated.53

The most solid foundation of Russia’s securitization narrative vis-à-vis Islam is based on the arbitrary division between heretic/parallel/extremist/fanatic and traditional/official/moderate Islam and Muslims in Russia. For the past three hundred years, there have been numerous occasions where Muslims who had fallen outside the Russian bureaucracy were securitized by the central authority. While the securitization language has evolved over time, this distinct quality of Russia’s securitization narrative vis-à-vis Muslims has hardly transformed.

Impact of the Western Discourse on Islam and the War on Terror on Russia’s Securitization Narrative

In this part, I examine the impact of the Western securitization narrative vis-à-vis Islam. Russia’s attempts to modernize in a European way began with the Petrine reforms in the early 18th century. While it was the European navy that allured Peter the Great, his modernization attempts enabled the ideas and attitudes developed in the West to influence Russia as well. Although the experience of Europe with the Muslims was significantly different, Russia has adopted Europe’s narrative of Islam on multiple occasions.

Early examples of such influence can be seen in Catherine II’s correspondence with Western intellectuals. For instance, the Empress was repeatedly encouraged by Voltaire to exterminate the two great scourges on earth: the plague and the Turks and to crush the Ottoman Empire in its weakness.54 The backing of enlightenment philosophers, who shaped public opinion throughout Europe, shaped the image of Muslims in Russia as well.55 In Europe, it was legitimate violence when applied to the Muslims that helped the Empress to appear less of a despot and more enlightened.

Russia adopted the Western securitization narrative during the Chechen uprising as well. The U.S. securitization of Islam in the late 20th century was a watershed move not only for the national security but also for global security –playing a significant role in every major power’s securitization narrative towards Islam. In Russia, securitization on religious grounds would gain ground as well, following the 9/11 attacks when Russia bandwagoned the U.S. security master narrative on Islam.56

Following the dissolution of the USSR, Chechnya declared independence under the name of Chechen Republic of Ichkeria. The ensuing battle between the Russian army and the Chechen forces followed by the Khasavyurt Agreement failed to bring stability to the region. In 1999, groups of Chechen fighters made an incursion into Dagestan and clashed with the police. It is noteworthy that it was later revealed that Russian billionaire Boris Berezovskiy was involved with the financing of the operation and the high-ranking Russian bureaucracy was hardly surprised when the incursion occurred.57 Nevertheless, this incident brought about a decree, from the Duma that associated the Chechen government with international terrorism.58The controversial Moscow apartment bombings on September 4, 1999, paved the path for the escalation of the securitization language. Russian State Duma59 promulgated another decree underlining the threat of terrorism.60 The National Security Concept of the Russian Federation that was promulgated in 2000 delegitimized the Chechen bid for independence and equated their separation efforts with terrorism.61 The generic image of Chechen fighters during the first Chechen War, as evident in their description in the news, was largely a group of cruel bandits terrorizing the region.62 At that point, Chechens’ clan-based social structures are debated within the framework of the image of an infamous Chechen mafia. The sanity of Chechen leaders who directed the insurgency was questioned as well. Prominent Chechen leaders, such as Dudaev and Raduev, were often described as mentally ill or loony.63

Russian official discourse linked the matter of regional insurgency to a global master narrative by magnifying the Islamic identity of the insurgents and their alleged connections with transnational terror networks responsible for the 9/11 attacks

Following the 9/11 attacks, this narrative was transformed within the framework of a U.S.-led global master narrative. The events of 9/11 significantly transformed the way Chechen forces are portrayed. In fact, Putin was the first leader to extend his support to Bush against global terrorism. After the attack, instead of liberally associating Chechen fighters with anything that is abnormal, the news began to represent the fighters with the image of those who were responsible for 9/11. Accordingly, the same forces began to be labeled as jihadis, mujahedeen and were associated with Bin Laden.64 This narrative enabled Russia to market its Chechnya campaign in the West and legitimized Russia’s obstinacy in preventing independence and the disproportionate violence applied by the state.

The transformation of Russia’s security narrative in its effort to counter Chechen resistance makes a clear case for the impact of the Western securitization narrative on Russian securitization narrative vis-à-vis Muslims. Russian official discourse linked the matter of regional insurgency to a global master narrative by magnifying the Islamic identity of the insurgents and their alleged connections with transnational terror networks responsible for the 9/11 attacks.

The consequences of Russia’s borrowing Western securitization narrative have been mixed. On the one hand, as in the case of Chechnya, Russia actively manipulated the Western narrative by dealing with a secessionist movement without any sanction. On the other hand, the securitization narrative of the West vis-à-vis Islam has also transformed the image of Islam and Muslims in Russia as well.

Conclusion

Russia’s encounters with Muslims have taken place through subjugation of the Turco-Mongol rulers, expansion towards the East of Volga region and competition with the Ottoman Empire around the coasts of the Black Sea. Accordingly, Russia has experienced the different faces of Islam and developed different reactions to its experiences. In addition, Russia’s openness to Western influence brought about the transmission of Western narrative of Islam to Russia.

This work provides multiple assessments on Russia`s securitization narrative on Islam. First, Russia`s experience of subjugation under Turkic-Muslim rulers for two centuries created a very deep negative memory which has a potential to be used in a securitization exercise. Second, Russia is prone to securitize a portion of a Muslim community when it expands its territories or influence towards a Muslim-inhabited region. In this type of securitization exercise, the portion of Muslims that do not cooperate with the central authority is at risk of being labeled in a way that suggests this community an illegality and anomaly. Lastly, Russia occasionally benefits from the way Islam is securitized by the West.

Appendix – Russia’s Securitization Narratives

Endnotes

- Commonly known as Catherine the Great.

- Ulama: Originally an Arabic word, ulama means the learned one. It is used to define the group of people who are madrasa graduates handling tasks related to judiciary, education and religious service within Islamic societies.

- Nicholas Onuf, Making Sense, Making Worlds: Constructivism in Social Theory of International Relations, (London: Routledge, 2012), p. 3.

- Nicholas Onuf, The World of Our Making, (Columbia SC: University of South Caroline Press, 1989), p. 2.

- Alexander Wendt, “Anarchy Is What States Make of It: The Social Construction of Power Politics,” International Organization, Vol. 46, No. 2 (Spring 1992), p. 394.

- Anthony Giddens, The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984).

- Alexander Wendt, “The Agent-Structure Problem in International Relations Theory,” International Organization, Vol. 41, No. 3 (1987).

- Alexander Wendt, “Constructing International Politics,” International Security, Vol. 20, No. 1 (Summer 1995), p. 73.

- Harry Gould, “What Is at Stake in the Agent-Structure Debate,” in Vendulka Kubalkova, Nicholas

Onuf and Paul Kowert (eds.), International Relations in a Constructed World, (London: Routledge, 1998), p. 83. - Onuf, The World of Our Making, p. 52.

- Barry Buzan, Ole Wæver and Jaap De Wilde, Security: A New Framework of Analysis, (London: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1998), p. 21.

- Ole Wæver, “Securitization and Desecuritization,” in Ronnie D. Lipschutz (ed.), On Security, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995), p. 54.

- Barry Buzan and Ole Wæver, “Slippery? Contradictory? Sociologically Untenable? The Copenhagen School Replies,” Review of International Studies, Vol. 23, No. 2 (April 1997), p. 241.

- Buzan, Wæver and De Wilde, pp. 23-34.

- Buzan, Wæver and De Wilde, p. 21.

- Buzan, Wæver and De Wilde, p. 36.

- Thierry Balzacq, Sarah Leonard and Jan Ruzicka, “‘Securitization’ Revisited: Theory and Cases,” International Relations, Vol. 30, No. 4 (2016), p. 496.

- Wæver, “Securitization and Desecuritization,” p. 55.

- Thierry Balzacq, “The Three Faces of Securitization: Political Agency, Audience and Context,” European Journal of International Relations, Vol. 11, No. 2 (June 2005), p. 172.

- Buzan et al., Security: A New Framework of Analysis, p. 14.

- The name ‘Tatar’ is originated from the name one of the nomadic tribes of Mongolia, which were subjugated by Chingiz Khan. The name Tatar is mistakenly used by the Russians to define not only the Mongols but also Turkic peoples under Mongol rule. Eventually, the name came to be associated with various types of Turkic-Muslim peoples under the Russian Empire.

- Galina Yemelianova, Russia and Islam: A Historical Survey, (New York: Palgrave, 2002), p. 32.

- Alexander Bennigsen and Marie Broxup, Islamic Threat to the Soviet State, (New York: Routledge, 2011), pp. 24-25

- The official name for this institution can be translated from the original Russian as Orenburg Muslim Spiritual Board (Orenburgskoe Magometanskoe Dukhovnoye Sobranie). In this work I prefer to refer it either as ‘Orenburg Spiritual Board’ or as the OMDS.

- Robert Crews, For Prophet and Tsar: Islam and Empire in Russia and Central Asia, (London: Harvard University Press, 2006), p. 2.

- Karl Marx, “A Contribution to Hegel’s Philosophy of Right: Introduction,” in Joseph J. O’Malley (ed.), Marx: Early Political Writings, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), p. 57.

- Dekrety Sovietskoi Vlasti, Vol. 1 (Moscow: Gosudarstvennoe Izdatel’stvo Politicheskoi Literatury, 1957), pp. 39-40.

- Sobranye uzakoneny i rasporyazheny pravitelstva za 1917-1918, (Moscow: 1942), pp. 91-96.

- Islamic charity organization that play a significant role within the Muslim communities.

- Alexandre Bennigsen and Chantal Lemercier-Quelquejay, Islam in the Soviet Union, (London: Pall Mall Press, 1967), p. 145.

- Aydar Yuriyevich Khabutdinov, Rossiiskie muftii ot Ekaterininskoi orlov do yadernoi epokhi (1788-1950), (Nizhny Novgorod: Mahinur, 2006), p. 52.

- David Motadel, Islam and Nazi Germany’s War, (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2014), p. 175.

- Eren Murat Taşar, “Soviet and Muslim: The Institutionalization of Islam in Central Asia, 1943-1991,” unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Harvard University, 2010, p. 461.

- Charles Halperin, The Tatar Yoke: The Image of the Mongols in Medieval Russia, (Bloomington: Slavica Publishers, 2009), pp. 7-21.

- Charles J. Halperin, “Omissions of National Memory: Russian Historiography on the Golden Horde as Politics of Inclusion and Exclusion,” Ab Imperio, Vol. 3, (2004) p. 132.

- Joseph Yeager, “Elite Russian Conceptions of Tatar Yoke: 1770-1930,” unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Missouri-Columbia, 2007, p. 7.

- Charles Halperin, “Soviet Historiography on Russia and the Mongols,” The Russian Review, Vol. 41,

No. 3 (July 1982), p. 322. - Marlies Bliz-Leonhardt, “Deconstructing the Myth of the ‘Tatar Yoke,”’ Central Asian Survey, Vol. 27,

No. 1 (March 2008), p. 37. - “Prezident porabotal dlya istorii,” Kommersant, (November 11, 2003).

- Tatyana Alyokhina, Leyla Merdieva and Tatyana Shchuklina, “The Ethnic Stereotype of Tatars in Russian Linguistic Culture,” Journal of Organizational Culture, Communications and Conflict, Vol. 20, (2016), p. 229.

- Bliz-Leonhardt, “Deconstructing the Myth of the ‘Tatar Yoke,”’ p. 38.

- Allen Frank, Islamic History and Bulghar Identity Among the Tatars and Bashkirs of Russia, (Leiden: Brill, 1988), p. 136.

- Lauran L. Van Merte, “The Struggle for Russia’s Past: Competing Regional History Institutions and Narratives,” unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Johns Hopkins University, 2008, p. 226.

- Crews, For Prophet and Tsar: Islam and Empire in Russia and Central Asia, pp. 316-318.

- Eren Murat Taşar, “Soviet Policies Toward Islam Domestic and International Considerations,” in Philip Muehlenbeck (ed.), Religion and Cold War a Global Perspective, (Nashville TN: Vanderbilt University Press, 2012), p. 461.

- Religious decree.

- Eren Murat Taşar, “Soviet Policies Toward Islam Domestic and International Considerations,” p. 517.

- John Russell, Chechnya: Russia’s War on Terror, (New York: Routledge, 2007), p. 66.

- Ramzan Kadyrov, Instagram, https://www.instagram.com/kadyrov_95/?hl=en.

- “Like Walking in a Minefield: Vicious Crackdown on Critics in Russia’s Chechen Republic,” Human Rights Watch, (August 10, 2016), from https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/08/31/walking-minefield/vicious-crackdown-critics-russias-chechen-republic.

- “Glava SMR muftiy sheykh Ravil’ Gaynutdin i muftiy Kryma khadzhi Emirali Ablayev prizvali yedinovertsev k splochennosti,” Ofitsialnyy Sait Dukhovnovo Upravleniya Musul’man Rossiyskoy Federatsii, (March 24, 2014).

- The Parliament.

- Natal’ya Raibman, “Verkhovnyy sud Kryma zapretil medzhlis krymskotatarskogo naroda,” Vedomosti, (April 26, 2016).

- Simon Dixon, Catherine the Great, (New York: Harper & Collins, 2010), pp. 202, 206.

- Frank Brechka, “Catherine the Great: The Books She Read,” The Journal of Library History, Vol. 4, No. 1 (January 1969), pp. 39–52.

- Mohiaddin Mesbahi, “Islam and Security Narratives in Eurasia” Caucasus Survey, Vol. 1, No. 1 (2003), p. 6.

- Andrey Babitskiy, “Prichiny napadeniya otryadov Basayeva i Khattaba na Dagestan v avguste 1999-go goda,” Radio Svoboda, (August 2, 2000).

- “O situatsii v Respublike Dagestan v sviazi s vtorzheniem na territoriiu Respubliki Dagestan nezakonnykh vooruzhennykh formirovanii i merakh po obespecheniiu bezopasnosti Respubliki Dagestan,” Postanovlenie Gosudarstvennoi Dumy Federal’nogo Sobraniia Rossiiskoi Federatsii N 4277-II GD, (August 16 1999).

- Lower house of Federal Assembly in Russia.

- “O situatsii v Respublike Dagestan, pervoocherednykh merakh po obespecheniiu natsional’noi bezopasnosti Rossiiskoi Federatsii i bor’be s terrorizmom,” Postanovlenie Gosudarstvennoi Dumy Federal’nogo Sobraniia Rossiiskoi Federatsii N 4293-II GD, (September 15, 1999).

- Vladimir Putin, “Kontseptsiya natsional’noy bezopasnosti Rossiyskoy Federatsii,” Ministerstvo Inostrannykh Del’ Rossiyskoy Federatsii, (January 10, 2000).

- Elena Pokalova, “Shifting Faces of Terror After 9/11: Framing the Terrorist Threat,” unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Kent State University, 2011, p. 102.

- John Russell, “Mujahedeen, Mafia, Madmen: Russian Perceptions of Chechens During the Wars

in Chechnya, 1994-96 and 1999-2001,” Journal of Communist Studies and Transnational Politics, Vol. 18, No. 1 (2002), pp. 77-78. - Pokalova, “Shifting Faces of Terror After 9/11: Framing the Terrorist Threat,” p. 157.