Introduction

The year 2021 has been so far a busy year for Turkey’s growing Africa policy. Over 10 African leaders and heads of state, including the Ethiopian Prime Minister, Sudan’s Sovereign Council chairman, and the African Union Commission chairperson, have visited Turkey. Reciprocally, in October, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has visited the three West African countries of Angola, Nigeria, and Togo where he also met with leaders of Burkina Faso and Liberia. In the same month, the Turkish metropolis İstanbul hosted the 3rd Africa-Turkey Economic and Business Forum that brought together around 2,000 participants, including representatives of 45 African countries, regional economic communities, and private sector representatives from both sides. The Forum, as well as Erdoğan’s recent Africa tour, were preparations for the 3rd Turkey-Africa partnership: a high-level gathering in İstanbul featuring heads of state and government from African countries and Turkey, representatives of regional economic communities and international organizations.

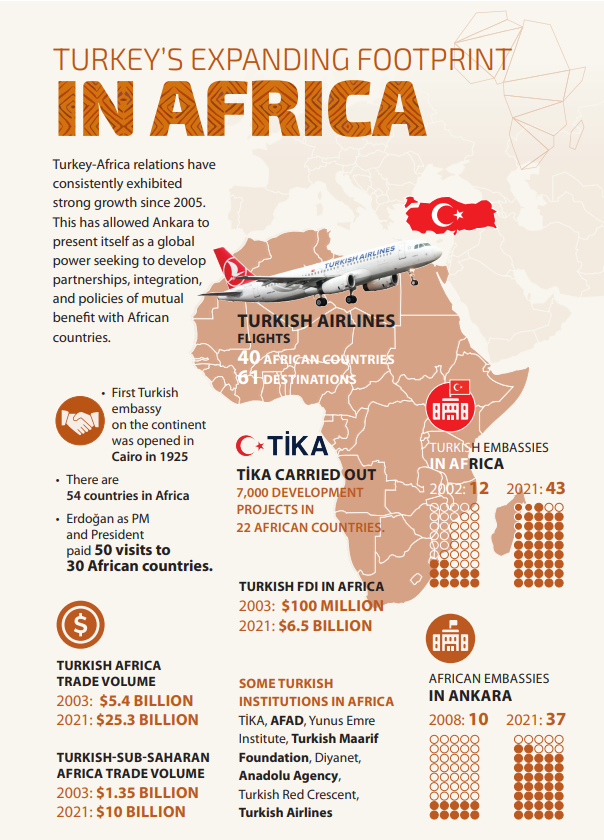

These are reflections of Turkey’s deepening ties with Africa. Turkey-Africa relations have consistently exhibited strong growth since Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AK Party) came to power in 2002. Trade has reached $25 billion, Turkish Airlines flies to more destinations in the continent than any other airline and Ankara has 43 embassies across the continent. Moreover, the number of African embassies in Ankara is now 37, compared to 10 in 2008. Turkey presents itself as a global power-driven by an ‘enterprising humanitarian’ foreign policy that is seeking to develop partnerships, integration, and policies of mutual benefit with African countries and reverse what Turkish officials call remnants of colonial policies and exploitation by the West. In response, however, there is a tendency among critics of Turkey’s renewed engagement with Africa to accuse Ankara of pursuing an aggressive neo-Ottoman agenda –often characterized as ‘anti-western’ and ‘pan-Islamism’– in Africa.

What is driving the evolving Turkey-Africa partnership and what is Turkey trying to achieve in Africa? In addressing this question, this commentary focuses on four dimensions: An overview of Turkey’s Africa initiative, a wide assessment of the Turkish engagement objectives on the continent, a discussion on African agency in the growing Turkish-African relations context, and a look at the future perspectives. These four dimensions help contextualize Turkey’s rising influence in Africa, with particular reference to Sub-Saharan Africa, and the role of African governments and African non-state actors in shaping and determining the nature of the renewed Turko-African relations.

Tracing the ‘Afro-Eurasian State’ in Africa

Turkey has a long-term commitment to increasing its influence in Africa. The momentum of the current Turko-African relations began during the 1960s- also known as Africa’s decade of decolonization. In 1968, Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia paid a state visit to Turkey, which was reciprocated by President Cevdet Sunay the following year. By recognizing the newly independent African countries and supporting the decolonization process, Turkey wished to establish economic and political relations with Africa. As a result, Ankara has opened diplomatic missions in several African countries, including Ethiopia, Nigeria, Kenya, and Senegal. Turkey’s ties with Sub-Saharan Africa, however, largely remained neglected in the following two decades due to the 1974 Cyprus crisis and a host of domestic political realities, including economic difficulties, repetitive military coups, and the rise of the PKK-led separatist movement.

Africa again featured Turkish foreign policy in the final years of the last century. In 1998, the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs adopted the Africa Action Plan –a set of diplomatic, political, economic, and cultural programs designed to introduce Turkey to Africa and set the tone for a renewed Turkish activism in the Sub-Saharan region. The implementation of this ambitious plan was hindered by coalition government problems; and the 2000-2001 economic crises characterized by lower growth rates, higher interest rates, and a wave of capital outflows. Nevertheless, the plan was restored once the short-lived liquidity crisis was over and the current ruling AK Party came to power in 2002. In the following two decades, successive AK Party-led governments pursued an ambitious strategy for engagement with individual African countries and the continent as a whole. The 1998 plan was refurbished in 2003 with the initiation of the strategy for developing economic relations with Africa. However, the declaration of 2005 as the ‘year of Africa’ could be considered the turning point of Turkey’s Africa policy and officially set the stage for Ankara’s expanding Africa footprint characterized by increasing trade and investment, increasing diplomatic presence, consistent high-level visits, and Turkey-Africa partnership summits.

While the practical rationale and an assessment of Turkey’s Africa policy achievements are discussed in the next section, it is paramount to theorize Ankara’s renewed engagement in Sub-Saharan Africa –a region historically considered as a faraway periphery ‘full of problems, hunger, diseases, and civil wars’ among Turkish policymaking circles.1 Although there might be several concepts to explain Turkey’s return to Africa, I use the end of the Cold War and the emerging power theories to contextualize Turkey’s renewed interest in Africa. Both concepts provide reasonable explanations for the extensive engagement of Turkey, which recently started to describe itself as an ‘Afro-Eurasian state,’ with the African continent.2

The collapse of the Soviet Union and the subsequent end of the Cold War in the early 1990s has had major repercussions for global and regional politics as the states tried to adjust themselves to the change in the world order. The new international realities resulting from this dramatic change has forced Turkey –a country whose geography straddles between Europe and Asia– to go on what Ziya Öniş calls ‘a search of identity’ foreign policy.3 The emergence of newly independent states in Central Asia and the proliferation of ethnonational conflicts in the Balkans and the Caucasus coupled with the disappearance of security concerns mainly posed by the Soviet Union provided Turkey with an opportunity to adjust to the post-Cold War global context. As a result, Turkey has reacted to the prevailing international system by assuming more ‘activist and assertive’ foreign policies in regional and global issues.4 Consequently, Ankara devised an activism-based course of action, looking simultaneously to the West and East, intended to define Turkey’s position in the post-Cold War global order. The new Turkish foreign policy has focused on generating soft power through Turkey’s history, geography, and identity. This has led to, among other things, Turkey’s improved relations with Middle Eastern countries and the establishment of closer links with regional bodies including the Organization of the Islamic Cooperation. Although Africa did not initially feature in this new activism, the continent has received significant attention in 1997 when the European Union blocked Turkey’s efforts to assume official candidacy mainly due to issues with Cyprus and neighboring Greece. This has fueled the 1998 Africa Action Plan adoption which called for developing political, economic, and business ties with Sub-Saharan Africa. Subsequent AK Party-led governments since 2002 have initiated what is known as a ‘multidimensional’ foreign policy and focused on diversifying Ankara’s relations with Africa via trade and investment, diplomacy, and humanitarian initiatives.

By recognizing the newly independent African countries and supporting the decolonization process, Turkey wished to establish economic and political relations with Africa

The post-Cold War international system has seen the development of the emerging power theory in global politics and economy. Although the ‘emerging power’ term remains vaguely defined in the international relations theory, there is a general consensus in academia that the country could be considered as an emerging power if it undertakes the process to expand its political and economic power faster than the rest. A key characteristic of emerging power states is that they generally have a lower level of development and democratization exposure and tend to assume semi-peripheral roles in global affairs. These states, according to Alden and Vieira, also view the post-Cold War international system with concerns on the global power hierarchy and actively seek to challenge “the position and assumptions of the leading states in the global North.”5 A NATO and G20 member, Turkey can be classified as an ‘emerging middle power’ defined as “the ability to oblige other states to take actions that they would not otherwise have taken and to resist pressure to do so from other states.”6 Buğra Süsler concurs with this definition and argues that “while Turkey is not a great power, it has considerable ability to act independently, resist pressure from great powers, and exert influence as a regional actor.”7 It is worth mentioning that Turkey’s impressive economic growth in the period 2002-2010 is credited for contributing to its foreign policy assertiveness and eventually providing it with an emerging middle power status. In the context of Africa, Turkey can be classified in this category because Ankara pursued an ambitious foreign policy towards the continent in the last two decades and it seeks regional and global influence, in which relations with Africa play an important role.

Drivers of Turkey’s Foray to Africa: 2002-Present

Several practical reasons explain the unimaginable progression of Turkey’s Africa policy under successive AK Party-led governments since 2002. These include the need to discover new economic opportunities in the Sub-Saharan region and present itself as a relevant regional and global actor different from traditional western players on the continent. This section is an assessment of key practical drivers of Turkey’s growing footprint in Africa, with particular reference to the Sub-Saharan Africa region.

Turkey is determined to promote its development model which combines economic development with humanitarian assistance by exporting it to Africa. Following the declaration of 2005 as ‘the year of Africa,’ Turkey has launched several initiatives that made Ankara a strategic partner in continental and regional organizations, such as the African Union and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, almost half of whose 57 members are African states. However, Turkey’s 2011 humanitarian intervention in Somalia and its subsequent state-building projects in the country have deepened Turkey’s influence in Africa, resulting in the emergence of the Turkish development and humanitarian aid model in the academia, alternatively known as ‘Ankara Consensus.’ Federico Donelli notes that this model, “which is both an alternative approach to African sustainability problems and a useful political discourse to foster Turkish ambitions as an emerging global power” could “explain the peculiar set of prescriptions that Turkey promotes in sub-Saharan Africa based on its own development experience that could be considered a mix between democratic liberalism (Washington consensus) and authoritarian capitalism (Beijing consensus).”8 Regarding Africa, the Turkish policymakers extensively use narratives of Global South solidarity often noting that what differentiates the Turkish model is ‘our focus on mutual respect.’9 Furthermore, the model burnishes Turkey’s anti-colonial rhetoric, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, by fashioning Turkey as ‘Africa’s friend and development partner’ which is against colonialism, imperialism, and other forms of exploitation. The anti-western discourse in Turkish public diplomacy towards Africa helps Ankara act as a counterweight against colonial powers, such as France and other European powers.

While Turkey is not a great power, it has considerable ability to act independently, resist pressure from great powers, and exert influence as a regional actor

Besides, the Turkish model contributes to Ankara’s assertive foreign policy to challenge the current global order. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan of Turkey is known for advocating for United Nations reform, arguing that the UN Security Council has failed to ensure global peace and justice. He has coined the phrase ‘The World Is Bigger than Five’ –a reference to the five UN Security Council members. In his recent book A Fairer World Is Possible, Erdoğan argues that the “UN Security Council is one of the main reasons for existing injustices around the world. The five permanent members are countries from Asia, Europe, and Americas, but there is no representation for African interests.”10 During his most recent Africa tour, the Turkish leader said the existing global injustice ‘will encircle Africa’ and asked African states to join Turkey in calling for comprehensive UN reform.11 From this perspective, the promotion of the Turkish development model in Africa is a strategic state policy to galvanize the support of the 54-strong African states to Ankara’s demand for a fairer world.

Source: Compiled by Insight Turkey, data provided by the author.

Source: Compiled by Insight Turkey, data provided by the author.

Through its engagement with Africa, Turkey seeks to uncover new economic opportunities. As previously mentioned, Turkey’s trade volumes with Africa reached $25 billion in 2020 –a fivefold increase from $5 billion in 2003– while trade volume with the Sub-Saharan region increased tenfold in the last decade. Turkey has been able to maintain its trade volume with Africa during the pandemic and is vying for the Africa Continental Free Trade Area in a bid to claim a bigger share of the African market. Currently, Turkey has joint business councils with 45 African countries, of which 40 are in the Sub-Saharan region.

By deepening trade ties with Africa, Turkey seeks to establish new markets for its manufactured goods in the continent. Turkish goods are slowly becoming popular among the African consumer markets because they are generally of a higher quality than Chinese products and are more competitive than European goods in terms of price. Turkey is also looking to find African markets for its construction industry. Turkish construction companies have already undertaken significant infrastructure projects in the continent, such as East Africa’s largest indoor sports facility in Rwanda, a 336 km high-speed railway in Tanzania, a 400 km railway in Ethiopia, and a 51 km-long railway project in Senegal, which is the first in the West African nation. The volume of infrastructure projects implemented by Turkish companies in Africa has reached over $71 billion, of which $19.5 billion is in the Sub-Saharan African region. Compared to Chinese rivals, the Turkish construction companies are praised for their willingness to transfer technology, increased flexibility in terms of letting the host country manage the projects and using English as a working language.12 Moreover, Turkish Airlines is another sign of Turkey’s increasing trade ties with Africa. With 61 destinations across the continent, the Turkish flag carrier currently flies to more African destinations than any other airliner, making the region more connected to the world.

Another possible explanation for Turkey’s deepening ties with Africa is the need to find a market for the Turkish defense and armaments industry. Turkey is currently home to seven of the world’s top 100 defense companies. With increased prestige, the Turkish defense and armaments industry is gaining attention from around the world and Africa is no exception. Turkey-produced defense equipment, such as armored vehicles and weapons, has been sold to several African countries, including Senegal, Kenya, and South Africa. In an attempt to open up markets for its armaments industry, Ankara has inked bilateral agreements with five Sub-Saharan African countries to cooperate in the production, procurement, and maintenance of defense and military equipment. This category includes the widely praised Turkish drone program, which has recently aroused African interest in the face of security threats in many parts of the continent. So far, it has been confirmed that Tunisia and Morocco have officially agreed on deals with Turkey, worth $80 and $69.6 million respectively, for the acquisition of several dozens of the Bayraktar TB2 unmanned drones. It has also been reported that Ethiopia recently placed orders for Turkish drones. Moreover, media reports allege that the promotion of the Turkish defense industry, especially the evolving drone program, topped President Erdoğan’s recent Africa visit.13 As a result, Angola and Nigeria have reportedly requested the purchase of Turkish-made unmanned aerial vehicles. Without much fanfare, the Turkish armed drones have become prestigious after their successful use in several conflicts, such as Libya, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Syria. It is no surprise that Africa is a region that Ankara considers an important destination for its drone sales.

President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan of Turkey is known for advocating for United Nations reform, arguing that the UN Security Council has failed to ensure global peace and justice

Finally, Turkey’s growing engagement with Africa is an extension of Ankara’s domestic politics. Following the failed 2016 coup attempt, Ankara has pursued an ambitious role in eradicating the worldwide influence of the Fetullah Terror Organization (FETÖ), which has been accused of masterminding the unlawful act to overthrow the Turkish government. Since then, Turkish leaders have been strongly pushing African countries to clamp down on the many FETÖ-affiliated schools and business networks. Consequently, the group has been slowly losing influence in the continent with the closure of dozens of its schools and the apprehension of some of its members by the Turkish government. So far, the Turkish Maarif Foundation, which was set up following the defeated coup to coordinate overseas Turkish schools, has acquired 216 FETÖ-linked education premises in 19 African countries. Furthermore, several African countries have either expelled the group members from their territories or extradited them to Turkey. Therefore, Turkey’s involvement in Africa features the fight against the Gülen Movement in Africa, making the continent more important for Turkish policymakers.

African Agency in the Turko-African Relations

The literature on external actors in post-Cold War Africa tends to focus on ‘the new scramble for Africa’ often portraying the continent as weak. By emphasizing Africans’ willingness or ability to negotiate political and economic projects, this section challenges simplistic analysis of African states as passive actors in the evolving Turkey-Africa relations. By doing so, African efforts in shaping Turkey-Africa ties are categorized into three main strategic policy areas.

African countries have used their agency at multiple levels of engagement and negotiation to attract Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and increase their bilateral trade with Turkey. Over the past two decades, African governments have been able to secure Turkish investment in the continent, which is currently about $7 billion. The main target sectors for Turkish investment in the continent are construction, textiles, household goods, mining, agro-processing, and electronics. Ethiopia is a case in point by attracting $2.5 billion –the largest Turkish FDI in Sub-Saharan Africa. Currently, more than 225 Turkish companies operate in Ethiopia and employ over 20,000 local workers.

Turkey’s involvement in Sub-Saharan Africa is not short-term activism, but it is likely to develop deeper over the next few years through trade, investment, political and diplomatic cooperation

The second strategic agency effort, in which African political actors have been exercising influence vis-à-vis their partnership with Turkey, has been to diversify economic and political partners to reduce dependency. African governments have sought to develop new political and commercial ties with Turkey over the years while maintaining ties with traditional western powers. The African Union granted Turkey observer status in 2005 and strategic partner in 2008 with the first-ever Turkish-Africa Cooperation summit taking place in İstanbul in the same year, where representatives from 50 African countries attended. These have paved the way for more Turkish political and economic involvement in Sub Sahara Africa, primarily through increased foreign missions, regular high-level visits, and establishing Turkey-Africa cooperation summits. With these engagements, African countries seek to capitalize on the Turkish economic activities that support “the African Union’s Agenda 2063 for ensuring inclusive growth and sustainable development of the continent” and at the same time tactically reduce dependency on traditional western actors and China.14

Finally, some African countries are using their engagement with Turkey to fuel their state-building process, and to some extent, secure the transfer of Turkish know-how. Somalia is a country that greatly benefited from Turkey’s Africa involvement. Turkey undertook its largest overseas humanitarian operation in 2011 to tackle a crippling famine that was devastating Somalia. Following the successful alleviation of the famine, the Somali government turned the Turkish involvement into a force to fuel its post-conflict state-building process. Consequently, Turkish transport infrastructure, hospitals, and schools have proliferated throughout the country in addition to Turkish personnel training of Somali security forces. The Turkish projects in Somalia are praised for their tangibility, respect for national ownership, and deploying staff to the field, despite the threats to security mainly from ISIS affiliate al-Shabaab terrorist group. Recently, some other Sub-Saharan African countries showed interest in the Turkish state-building projects in the form of security, peace-building, and mediation initiatives. These include Sudan who accepted a Turkish mediation offer to end its border dispute with Ethiopia15 and Angola who requested the Turkish drones during Erdoğan’s recent visit, in which he said Turkey will share its expertise in the security sector.16 All these symbolize the seriousness with which African politicians view Turkey and most importantly how African countries have been astute in their engagements with Ankara in terms of exercising leverage in the evolving Turkish-African partnership.

Looking Ahead

The current Turkey-African relations trajectory will likely continue for the foreseeable future. I argue that Turkey’s involvement in Sub-Saharan Africa is not short-term activism, but it is likely to develop deeper over the next few years through trade, investment, political and diplomatic cooperation. These will certainly allow Turkey to continue presenting itself as a reliable and alternative partner to former colonial powers, as well as China and Russia, on the continent.

As many African countries are facing conflicts and security threats by non-state armed actors, a particular area to watch is the proliferation of the Turkish defense and armaments industry to the continent. Of particular relevance in this context is Turkey’s drone program that has aroused the interests of African leaders after its recent successful use in international conflicts. Although Turkey currently does not rival the U.S. and China in Africa, it is safe to assume that Turkey’s security push in Africa will face competition from traditional European powers. This will be more evident if Ankara decides to develop security ties with the Sahel region –a traditional French sphere of influence. Unlike the Horn of Africa where Turkish security involvement does not present challenges from the extra-regional actors, the Sahel could turn into a point of contention should Turkey decide to be present militarily in former French colonies, such as Mali and Niger. Media reports emerging in mid-2020 alleged that Turkey and Niger had concluded a defense agreement that grants Ankara a military foothold in the country and includes plans for Turkish personnel to train and support Nigerien troops fighting Boko Haram and other militant groups.17 Despite these, however, one cannot disregard the possibility of Turkish-French cooperation in Sub-Saharan Africa to curb China’s growing influence in the region.

Furthermore, Turkey’s domestic situation warrants a closer watch in the next few years with regard to Ankara’s Africa policy. An impressive economic performance between 2000 and 2010 has greatly contributed to Ankara’s deepening engagement with Africa, especially the Sub-Sahara region. However, economic woes in the past decade primarily due to the Syrian civil war, the 2016 coup attempt, the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the ongoing currency crisis have all contributed to slowing economic growth in recent years. Although not presenting an immediate challenge, these factors could potentially contain Turkey’s growing footprint in the African continent.

Endnotes

1. Chigozie Enwere and Mesut Yılmaz, “Turkey’s Strategic Economic Relations with Africa: Trends and Challenges,” Journal of Economics and Political Economy, Vol. 1, No. 2 (2014), p. 221.

2. “Turkey’s Erdogan Pivots to Africa for Trade,” Africanews, (October 28, 2021), retrieved from https://www.africanews.com/2021/10/28/turkey-s-erdogan-pivots-to-africa-for-trade/.

3. Ziya Öniş, “Turkey in the Post-Cold War Era: In Search of Identity,” Middle East Journal, Vol. 49, No. 1 (1995), pp. 48-68.

4. Kemal Kirişçi, “The End of the Cold War and Changes in Turkish Foreign Policy Behaviour,” Foreign Policy, (November 29, 2016), retrieved, from https://foreignpolicy.org.tr/the-end-of-the-cold-war-and-changes-in-turkish-foreign-policy-behaviour-kemal-kirisci/.

5. Chris Alden and Marco Antonio Vieira, “The New Diplomacy of the South: South Africa, Brazil, India and Trilateralism,” Third World Quarterly, Vol. 26, No. 7 (2005), p. 1077.

6. William Hale, Turkish Foreign Policy since 1774, 3rd , (London: Routledge, 2013), p. 1.

7. Buğra Süsler, “Turkey: An Emerging Middle Power in a Changing World?” LSE Ideas, (2019), retrieved from https://lseideas.medium.com/turkey-an-emerging-middle-power-in-a-changing-world-df4124a1a71f.

8. Federico Donelli, “The Ankara Consensus: The Significance of Turkey’s Engagement in Sub-Saharan Africa,” Global Change, Peace & Security, Vol 30, No. 1 (2018), p. 58.

9. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, “Turkey: Africa’s Friend, Compatriot and Partner,” Al Jazeera, (June 1, 2016), retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2016/6/1/turkey-africas-friend-compatriot-and-partner.

10. “In His New Book, Erdogan Says the UN Needs to Be Reformed for Global Justice,” TRT World, (September 6, 2021), retrieved, from https://www.trtworld.com/magazine/in-new-book-erdogan-says-the-un-needs-to-be-reformed-for-global-justice-49755.

11. “Erdoğan Calls for a Fairer World, Urges Africa to Act Together,” Daily Sabah, (October 18, 2021), retrieved from https://www.dailysabah.com/politics/diplomacy/erdogan-calls-for-a-fairer-world-urges-africa-to-act-together.

12. “Laying the Tracks: The Political Economy of Railway Development in Ethiopia’s Railway Sector and Implications for Technology Transfer,” Global Development Policy Center, (February 8, 2021), retrieved from https://www.bu.edu/gdp/2021/02/08/laying-the-tracks-the-political-economy-of-railway-development-in-ethiopias-railway-sector-and-implications-for-technology-transfer/, pp. 1-25.

13. “Erdogan Tours Gulf of Guinea with His Military Procurement Team,” Africa Intelligence, (October 15, 2021), retrieved from https://www.africaintelligence.com/central-and-west-africa_diplomacy/2021/10/15/erdogan-tours-gulf-of-guinea-with-his-military-procurement-team,109698781-gra.

14. Gökhan Ergöçün, “Turkey-Africa Economic and Business Forum Releases Joint Declaration,” Anadolu Agency, (October 21, 2021), retrieved from https://www.aa.com.tr/en/africa/turkey-africa-economic-and-business-forum-releases-joint-declaration/2399207.

15. “Sudan Accepts Turkey Mediation Offer to End Disputes with Ethiopia,” Middle East Monitor, (September 20, 2021), retrieved from https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20210920-sudan-accepts-turkey-mediation-offer-to-end-disputes-with-ethiopia/.

16. “Angola Requested Turkish-Made UAVs, Armored Carriers,” M5 Dergi, (October 18, 2021), retrieved from https://m5dergi.com/defence-news/erdogan-says-angola-requested-turkish-made-uavs-armored-carriers/.

17. “Turkey Forges Military Pact with Niger, Libya’s Neighbour,” Middle East Monitor, (July 25, 2020), retrieved from https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20200725-analysis-turkey-forges-military-pact-with-niger-libyas-neighbour/.