To what extent does the “Turkish vote” matter in German elections? Can one speak of a unified Turkish vote? Is the Turkish minority adequately represented in proportion to its share in the population? What are the mistakes Turkey made in its policy towards Germany’s Turkish minority? What are the implications of the 2009 elections for German-Turkish relations and Turkey’s pursuit of EU membership? What are the future political prospects of Germany’s Turkish minority?

The historic victory of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) in 1998, and the reign of the SPD-Green coalition government under the leadership of Gerhard Schröder between 1998 and 2005, represented the political constellation most favorable to the interests of the Turkish minority in Germany. This was when the historic citizenship reform of 1999 was passed, allowing for an ever increasing number of second and third generation Turkish immigrants to acquire German citizenship. However, the government’s failure to allow for dual citizenship was a major disappointment among the Turkish minority. Ever since 2005, Turks lost political clout with every successive election and government. The Christian Democratic Union (CDU/CSU) victory in 2005, which culminated in the CDU/CSU-SPD coalition government, was a mixed blessing for the Turkish minority in the sense that while the CDU leadership in the government was negatively disposed towards both the Turkish minority in Germany and Turkey’s membership in the EU, the SPD half of the “Grand Coalition” limited the excesses of the Christian Democrats. Following the September 2009 elections and the formation of the CDU/CSU and the liberal FDP coalition government, the Turkish minority in Germany, as well as Turkey in its pursuit of EU membership, can expect more political obstacles and troubles. The FDP, although liberal, is both not nearly as powerful as the SPD to balance the right wing policies of the CDU/CSU and it is not nearly as supportive of migrant interests and is as opposed to a culturalist stance in foreign policy as the SPD has historically been. The FDP has also had a much more tenuous relationship with the Turkish minority than the SPD, the Greens, or the Left party.

Turks’ engagement with German politics began in the 1970s in an indirect fashion through the SPD-affiliated labor unions

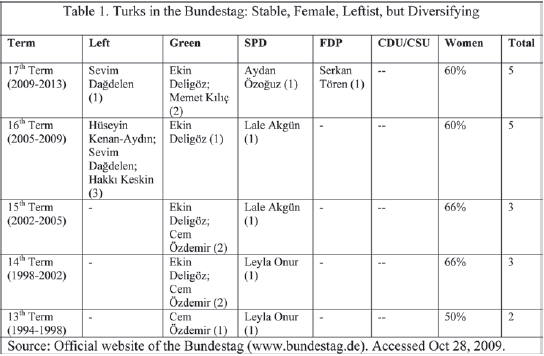

Turks in the Bundestag: Stable, Underrepresented, Female, Leftist but Diversifying

There are certain well-established trends as well as new developments in the representation of the Turkish minority in the German parliament, the Bundestag. In comparing the 17th (new) Bundestag elected in September 2009 with the 16th Bundestag elected in 2005, one sees that the number of members of Turkish background1 is the same: five of the 614 members of the 16th Bundestag (2005-2009), and again five of the 622 members of the 17th Bundestag (2009-2013) are Turkish. This number corresponds to 0.8% of the Bundestag. Considering that the Turkish resident population of Germany is estimated at around 3 to 3.5 million, corresponding to about 3.6% to 4.3% of Germany’s population of 82 million, the number of Turkish parliamentarians is indeed low. At this ratio, between 20 and 27 members of the Bundestag should have been of Turkish descent. However, considering that at most 800,000 (but perhaps as low as 600,000) of the Turks in Germany have citizenship, one can compute that only 1% of the citizenry is Turkish, even if up to 4% of the resident population can be considered of Turkish descent. Based on this adjustment based on “citizenship”, one has to conclude that the proportion of Turks in the parliament corresponds to (or is only slightly lower than) their proportion within the citizenry.

Table 1 demonstrates some important trends. Turks’ engagement with German politics began in the 1970s in an indirect fashion through the SPD-affiliated labor unions, most importantly, the DGB, the Federation of German Labor Unions.2 Until the 1990s, the number of Turks with German citizenship was negligible. This number stood at 8,166 in 1986, corresponding to 0.01%, or one in ten thousand of the Germany citizenry.3 Therefore, in the 1970s and 1980s Turkish immigrants channeled their political activism through labor unions, civil society, and non-parliamentary political forums where they could vote and run for elections without being a citizen. The founding of the Green Party (Die Grüne, “the Greens”) out of the 1960s protest movement and what was known as the “extra-parliamentary opposition” allowed for a breakthrough in Turkish representation and visibility. The Greens did not require German citizenship as a prerequisite for membership and participation, and hence most immigrants, who did not and could not acquire German citizenship, joined the Green Party. As a result, many Turkish political figures such as Cem Özdemir, Ekin Deligöz, Ozan Ceyhun, and Rıza Baran, made their first appearance in the political scene through the Green Party. Prior to the appearance of the Green Party, Turks were exclusively linked to the SPD, and after the appearance of the Greens and their entry into the Bundestag in 1982, Turks were either affiliated with the SPD or the Greens for the next two decades.

Among other factors, the disappointment with the SPD-Green coalition government’s citizenship reform in 1999, which did not allow for dual citizenship, led to further diversification of the political landscape among the Turks, with some joining the successor of the former East German communists, the PDS (Party of Democratic Socialism), which was renamed the Left Party (Die Linke) after its merger with a leftist faction that split off from the SPD led by Oskar Lafontaine. As can be seen, in the previous (16th) parliament (2005-2009), three of the five Turkish members of the parliament, corresponding to 60% of Turkish representation, belonged to the Left Party. The most recent election seems to have carried the diversification of Turkish representation to another level with the liberal FDP having a Turkish representative in the Bundestag for the first time in its history. In short, in the earlier stages of their experience in German politics, Turks were uniformly behind the SPD. This uniformity gave way to a bifurcation with the appearance of the Greens. The reunification of Germany in 1991 and the disappointment with the SPD-Green coalition government after 2000 led to a tripartite reordering of Turkish preferences, with the Left Party claiming a share of the Turkish vote and representation. The elections of September 2009 further augmented this process by adding the FDP as the fourth actor into the German-Turkish political scene.

Evolution of Turkish Representation: Causes of Diversification or Fragmentation?

The political evolution of the Turkish-German vote can be described optimistically as diversification or pessimistically as fragmentation, and there is truth to both descriptions based on different interpretations of the causes. On the one hand, the fact that the Turkish vote and representation are no longer uniformly “captured” by the SPD or the Greens, might provide an incentive for different parties to try to appeal to the Turkish minority’s concerns with new promises and policies. In other words, this could be a symptom of a “competition” to better serve the interests of the Turkish minority. There is some truth to this proposition since the Greens, by taking a much more pro-immigrant stance starting in the 1980s, pushed the SPD to adopt policies that are more responsive to the needs of the immigrants. On the other hand, however, this is only the positive dimension of the diversification story, what one can call a “diversification due to positive competition.” As already suggested above, there was also a process of “fragmentation through disappointment”, whereby Turkish politicians fled from one political party to another because of their disappointment with their current parties. Unsurprisingly, this political flight seems to have been from the center left further to the left. Disappointed with the relative unresponsiveness of the SPD to their demands, Turks sought a solution to their problems in the Green Party, which appeared to be the left-liberal and environmentally sensitive alternative of the SPD, throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Disappointment with the Greens, too, especially in the process of reforming the citizenship law, saw some Turkish politicians moving to the Left Party, which is the successor of the formerly East German Communist Party. This framework explains the growth of the left but leaves the adherence to the FDP mostly unexplained. Perhaps disappointment with the left in part, and the existence of a small, nascent Turkish entrepreneurial class, explains the adherence to the FDP among a small segment of the Turkish-Germans.

Since Turkish political activism in Germany has been exclusively channeled through and targeted towards left-wing political movements and parties, Turkish politicians and activists were directly affected by the fragmentation of the left and the weakening of the SPD

A good example of a politician who went through this process is Hakkı Keskin, one of the most prominent immigrant politicians and civil society leaders since the 1960s. The leader of the Turkish Students Federation in Germany (1968-1971), the president of the Federation of Social Democratic People’s Organizations (1972-1977), and a founder and president of both the Union of Turkish Immigrants (1986-1998) and the Turkish Society of Germany (1995-2005), he has been involved with many forms of Turkish activism from student movements to labor unions, civil society organizations, and political parties. Apart from briefly serving as an expert in Turkey’s State Planning Organization (DPT) during Bülent Ecevit’s term in office in 1979, Keskin owes his entire political career to the Turkish minority in Germany. After decades of grassroots organizing and agitation for immigrant rights as a member of the SPD, Keskin became disillusioned with the SPD’s timidity in the face of the CDU/CSU’s pressures in the process of the citizenship reform and left the SPD after the failure of the government to allow for dual citizenship for the Turks.4 Keskin joined the Left Party in protest and was elected into the Bundestag in 2005. He left German politics with the 2009 elections, and directed his efforts to Turkish politics, becoming a columnist in the Turkish daily Cumhuriyet.

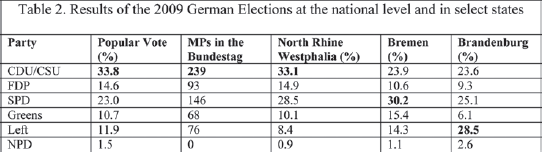

A third perspective on the “diversification” of Turkish representation would see this process as mirroring the fragmentation of the German left over time, in contrast to the relative stability of the right/conservative opinion represented by the CDU/CSU. Indeed, while the CDU/CSU has remained the sole and unchallenged representative of the conservative political scene in Germany, the left has split at least twice since the early 1980s, in the end dividing the leftist vote into three parties, the SPD, the Greens, and the Left. Since Turkish political activism in Germany has been exclusively channeled through and targeted towards left-wing political movements and parties, Turkish politicians and activists were directly affected by the fragmentation of the left and the weakening of the SPD. The first fracture occurred in the early 1980s with the entry of the Greens into the Bundestag, and the second fracture occurred in the early 2000s with the creation of the Left Party. In the 1960s and 1970s, the German political scene was defined by a large conservative party, the CDU/CSU, and a large social democratic party, the SPD, and a small liberal democratic party, the FDP, that became a coalition partner to whichever of the two large parties emerged victorious from the elections. In contrast, at present (2009), while the CDU/CSU and the FDP still remain the uncontested and sole representatives of the conservative and liberal political forces respectively, the leftist political currents, where the Turkish political leadership remains, is split between the SPD, the Greens and the Left. As a result, even though the total vote of the left-wing parties reached 45.6% as opposed to the 33.8% of the CDU/CSU in 2009, the latter emerged as the victor of the election and hence the partner of the liberal FDP, which garnered 14.6% of the vote (Table 2). The novelty of the 2009 election has been the appearance, for the first time, of a Turkish representative in the liberal FDP.

As Table 2 demonstrates, there is significant variation across different regions (Länder) of Germany, with the Left Party and/or the SPD dominating some regions, while the CDU/CSU dominates others. There is no region where the Greens or the FDP dominate. While even North Rhine Westphalia, the state with the largest number of Turks in absolute terms, went for the CDU, the formerly East German state of Brandenburg had the Left Party leading, closely followed by the SPD, with the CDU/CSU only in third place. In Bremen, the smallest city state in Germany (the other two city states are Hamburg and Berlin), the SPD won handily against the CDU, which captured less than a quarter of the vote, and the SPD, the Greens, and the Left together garnered three-fifths of the total vote. Regional variation along ideological lines continues to be an enduring feature of politics in Germany almost two decades after the reunification.

Consequences of Diversification or Fragmentation of Turkish-German Politics: Weakness or Strength?

At a first glance, the diversification of Turkish-German representation can be seen as an obvious blessing for the Turkish community: By preventing the association of Turks with one political party only, as used to be the case with the SPD, such diversification encourages multiple political parties to be attentive and responsive to the needs and demands of the Turkish community. However, as outlined above, the diversification of Turkish representation closely parallels the decline of the SPD, and the decline of the SPD corresponds to a decline in the potential of the immigrants at large and Turks in particular to have a greater influence in government.

However, such diversification might also be representative of the economic, social, ideological, and cultural diversity that is present within the Turkish community, especially as it has developed over the decades. When Turkish immigration to Germany began in 1961, those who immigrated were, by definition, industrial workers, the proletariat, the ideal constituency for the SPD. However, almost 50 years and three generations after the beginning of the worker migration, many Turks are not industrial laborers anymore: Some are small business owners themselves, many others are unemployed, and some have joined the ranks of white-collar professionals, artists, academics, and even state employees. Hence, their socio-economic profile no longer makes them a backyard of the SPD, providing an opportunity for other political parties to recruit from and appeal to the Turkish electorate. For example, Serkan Töre’s election as the first member of the parliament of Turkish origin for the FDP might give voice to the fledgling Turkish entrepreneurial class in Germany.

Representation Gap Persists: Conservative Turks and their Leftist Representatives

The diversification of political representation notwithstanding, another well-established feature of Turkish-German politics persist to this day: Despite being socially conservatives in their attitudes towards many aspects of German society, the Turkish minority is represented by some of the most left-liberal figures in the political spectrum. This is the essence of what I describe as the “representation gap” of the Turkish minority in Germany. The conservative social, cultural, and religious views of the Turkish minority are not expressed by their political representatives. This was most obviously revealed in a controversy over the headscarf in Germany. While the Turkish community by and large opposed the headscarf ban against state employees (such as teachers) in some German states, two of the most prominent Turkish members of the Bundestag, Lale Akgün of the SPD and Ekin Deligöz of the Greens, urged Turkish women to cast away their headscarves, much to the consternation of the Turkish electorate.5 Cem Özdemir (Greens) and Hakkı Keskin (Left) criticized the remarks of Akgün and Deligöz.6

This representation gap is likely to persist as long as the conservative CDU/CSU seeks to benefit from the anti-immigrant views that are widespread in the German public. Rationally speaking, the CDU/CSU has little incentive to reach out to the small Turkish minority at the risk of losing segments of its core constituency to far right parties such as the Republicans and the National Democratic Party of Germany (NPD). Although the NPD received a small, but not insignificant, 1.5% of the vote in the latest elections, it has notably gotten more than 3% of the vote in Mecklenburg-West Pomerania (Angela Merkel’s region) and in Thuringia, and 4% in Saxony.7 Although the NPD is still far from clearing the 5% threshold needed to enter into the Bundestag, along with the far right Republicans (Republikaner), which received 0.4% of the vote nationally, the two far right parties can chip away those voters from the CDU/CSU that have strong anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim, and/or racist views.8

The Greatest Political Obstacle for the Turkish Minority in Germany: Citizenship

The number one priority for Turkey in its policy towards the Turkish minority in Germany should be to help and expedite, and by no means hinder, the naturalization of Turkish residents of Germany, i.e., their acquisition of German citizenship. If the current 600,000 to 800,000 German citizens of Turkish descent were to quadruple to 3.2 million, which could happen if there were a conscious policy to do so, the Turkish minority could be a demographic-political force (at 4% of the national electorate) to be reckoned with in German politics. With 4% of the vote, they could be the difference between winning and losing an election, which could produce governments that are positively disposed towards Turkey’s membership in the EU and the social and economic concerns of the Turkish minority. This has already happened once. In the 2002 general elections, Gerhard Schröder’s SPD received only 9,000 votes more than the combined party list votes for the CDU/CSU (18,484,560 for the SPD as opposed to 18,475,696 for the CDU/CSU combined). In the same election, the SPD’s coalition partner, the Greens, received almost 600,000 more votes and six more seats than the FDP, hence securing a clear SPD-Green majority. However, has the SPD fallen behind the CDU/CSU in the popular vote and/or in the seats it won, the legitimacy of a SPD-led government could have been called into question. In this very close race between the SPD and the CDU/CSU where the difference was less than 10,000 votes, the Turkish-German voters, who already numbered in hundreds of thousands, made a difference by overwhelmingly voting for the SPD and the Greens. According to Politbarometer surveys conducted in late 2001 and 2002, 62% of Turkish-German citizens intended to vote for the SPD, followed by 22% for the Greens, and only 11% for the CDU/CSU, 3% for the FDP, and 3% for the PDS.9 Asked about their preference as to who should lead Germany as its next chancellor, 73% preferred SPD’s Schröder while 17% preferred the CDU/CSU’s candidate Edmund Stoiber.10 In short, one can surmise that if the Turkish-German voters did not so overwhelmingly vote for the SPD and the Greens, or if they did not vote at all, the SPD would in all likelihood have fallen behind CDU/CSU in the 2002 general elections.

The acquisition of citizenship is a sine qua non for the immigrants’ integration and attainment of power in the politics of their new society

Turkey made major mistakes in approaching Germany’s Turkish minority in the past, and it continues to commit some of these key mistakes to this day. The most important of these mistakes concern Turkey’s overall attitude towards the citizenship of Turkish immigrants in Germany. As was mentioned earlier, and as it must be obvious from the outset to anybody with a minimal knowledge of politics in the age of nation-states, “citizenship” is a prerequisite for voting, running for office, and for participating in most political activities and functions in a modern state. As such, the acquisition of citizenship is a sine qua non for the immigrants’ integration and attainment of power in the politics of their new society, and this general rule applies to the Turkish immigrant minority in Germany as well. However, a legal-political peculiarity of the host (German) society played a crucial role in seriously delaying and distorting the integration of Turkish immigrants into German politics and society. Until the coming to effect of a new citizenship law in 2000, passed in 1999, the German citizenship law allowed the naturalization of non-ethnic German immigrants only in the rarest conditions. Even children born in Germany but to immigrant parents were not granted German citizenship. Therefore, the pool of German citizens of Turkish descent was rather limited before 2000, and it is still somewhat small, at 1% of German citizenry, even today.

In 1999, the citizenship law was changed to allow for children born in Germany to immigrant parents who have been legal residents in Germany to acquire German citizenship, if they renounce their Turkish citizenship between the ages of 18 and 23. This law also allowed for the naturalization of immigrants who lived in Germany, fully employed and uninterrupted, for at least eight years, provided that they also fulfill some other prerequisites in addition to any additional conditions that the local state governments may require (e.g., citizenship or language tests, etc.). The new law was a disappointment for the Turkish minority because it expressly prohibited dual citizenship, even though it was a well-known fact that the Turkish immigrants wanted to keep their Turkish citizenship for a myriad of financial, social, cultural and psychological reasons. As a result, in order to acquire German citizenship, Turks have to renounce their Turkish citizenship and be denationalized by Turkey. This fact alone prevented about three quarters of the Turks in Germany from getting German citizenship.

Turkish governments have made many mistakes in the past and present on the citizenship question. First, and most importantly, Turkey made it difficult for Turkish immigrants to renounce their citizenship. In order to acquire German citizenship, Turks have to get a confirmation from Turkish consulates that they are no longer Turkish citizens. However, Turkey made it obligatory for Turkish immigrants in Germany to perform military service, or rather the paid version of it, in order to be released from Turkish citizenship. This requirement could be a major burden for workers, many of whom were unemployed or in low paid jobs, since paid military service entails paying a monetary sum in addition to going to Turkey to perform military duties for three weeks. Therefore, it would be a major improvement if Turkey exempted Turkish immigrants from military service if they want to be released from Turkish citizenship (i.e. if they want to give up their Turkish citizenship for another, in this case German, citizenship).

Turkish-Germans constitute the overwhelming majority of Muslims in Germany, and are by far the largest significant non-Christian population in this country

Alternatively, Turkey could have changed its own citizenship law to make it impossible for anybody to lose his/her Turkish citizenship, in which case the German government would have been obliged to recognize dual citizenship for Turks as it does for Iranians, Greeks, and other immigrants whose home country makes it impossible for them to lose their citizenship under any condition. The reformed citizenship law of 2000 also recognizes this fact, and allows for the dual citizenship of immigrants who are unable to give up their original citizenship. Although this would clearly be the best solution for the citizenship predicament of the Turkish minority, it is clearly more difficult from a political standpoint to change Turkey’s citizenship law to accommodate the needs and interests of the Turkish immigrant minorities abroad.

Finally, Turkish governments in the past could have encouraged the Turkish minority in Germany to acquire German citizenship. This was indeed done by Prime Minister Erdoğan in a visit to Germany but it should have been done much earlier and much more systematically. Moreover, if the Turkish government is honest in desiring the naturalization of the Turkish minority in Germany, it can make the necessary legal changes in Turkey to allow for the Turkish immigrants in Germany to retain their claims to inheritance and social security even after losing their Turkish citizenship in order to acquire German citizenship. Such a reform in Turkish laws would remove the financial incentives that prevent some immigrants from choosing German citizenship. In short, Turkey’s attitude in the past has also contributed to the obstacles preventing the formation of a multicultural society in Germany. However, since our focus in this article is the Turkish resident population in Germany, the larger share of the responsibility falls on the German government. Turkish-Germans constitute the overwhelming majority of Muslims in Germany, and are by far the largest significant non-Christian population in this country. It is also the immigrant group that the German media and politics focus most on, and therefore examining their demands and representation provides us with a good lens through which to examine debates about ethno-religious diversity in Germany.

There are only three Islamic schools in all of Germany, whereas there are 140 Islamic schools in Britain and 48 Islamic schools in Netherlands, both with much smaller Muslim populations

Obstacles to Religious Observance: Mosques, Islamic Instruction, and Headscarves

In their comparisons between France, Germany, and Britain, many scholars such as Fetzer and Soper have concluded that France has been the most restrictive and Britain the most accommodating towards Islamic religious observance, while Germany occupies the middle position between the two.11 Ahmet Kuru, for example, argues that there are 2,400 mosques in Germany, corresponding to 1 mosque per 1,375 Muslims (he considers the Muslim population to be 3.3 million), a ratio that is higher than in France (1 per 2,670) but lower than in Britain (1 per 1,071).12 However, while Kuru counts 2,400 mosques in Germany, mosques with minarets are only a small fraction of that number, and even these few mosques with minarets face a huge opposition from the non-Muslim majority. The most spectacular of such Islamophobic mobilizations occurred against the building of the largest mosque in Germany in Cologne.13 The opposition to the mosque was headed by the local far-right party the Pro Cologne, which holds five of the 90 seats in the city council. Nonetheless, after the controversy captured the attention of the national and international media, the city council approved the building of the mosque, and the DITIB, the Turkish religious organization in charge of raising the funds, began the process of collecting the US$20 million necessary for its building.14

Kuru also noted that there are only three Islamic schools in all of Germany, whereas there are 140 Islamic schools in Britain and 48 Islamic schools in Netherlands, both with much smaller Muslim populations.15 The problem of providing Islamic religious instruction is compounded in Germany by the fact that there is no nationally unified organization for the faith community as a whole and yet there are multiple, competing Muslim organizations in Germany.16 On a similar note, the Alevi community of Germany, unified under the Federation of Alevi Unions in Germany (Almanya Alevi Birlikleri Federasyonu, AABF), made use of this provision, and an “Alevi religion course” (Alevitischer Religions Unterricht) was taught in 30 schools in four German states (North Rhine Westphalia, Bavaria, Baden Württemberg, and Berlin), including the two most populous ones, as of October 2008, and plans were made to introduce it in two other states (Hessen and Lower Saxony) in 2009.17

Political influence of the Turkish minority in Germany still compares favorably with that of Muslim minorities in some of the other European countries

Germany has only been partially accommodating to Muslim women wearing headscarves. Although students are not forbidden from wearing headscarves, many states in recent years have prohibited teachers from wearing headscarves. This restriction is interpreted to apply to civil servants at large.

Concluding Remarks: The Turkish Minority in Germany in a Comparative Perspective

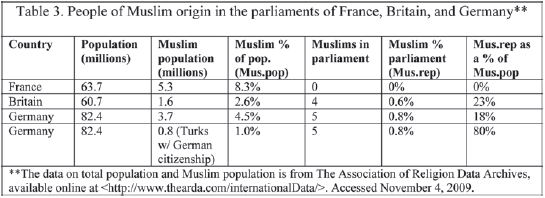

Despite the many shortcomings reviewed above, the political influence of the Turkish minority in Germany still compares favorably with that of Muslim minorities in some of the other European countries. Following a familiar pattern of comparison, if we choose to compare Germany with France in terms of the Muslim minority’s presence in the political arena, we arrive at a surprising result. Although between 5 and 6 million people of Muslim origin, representing 8% to 10% of the total population, live in mainland France, not a single member of the French House of Representatives is of Muslim origin.18 In Britain, out of a group of 645 members of Parliament, a total of four members are of Muslim origin,19 all of them from the Labour Party, representing 0.62% of all members of Parliament.20 There are no Muslim MPs from the Conservatives or the Liberal Democrats, the other two major parties in British politics, and neither from the myriad of smaller parties and independents. In contrast, as has been reviewed earlier, there are five members of the Bundestag of Muslim origin, all of them immigrants from Turkey, distributed across four of the five major political parties in Germany today.

Compared to the political representation, or lack thereof, of Muslim minorities in the French parliament, the story of the German Turks is a remarkable success. Compared to the political representation of Muslims in the British Parliament, the Turkish/Muslim representation in the Bundestag appears to be significant, especially when one considers how small these numbers are. Furthermore, two Turkish members entered into the Bundestag in 1994, which was three years prior to the entry of the first person of Muslim origin, Mohammad Sarwar of Glasgow, into the British Parliament. Most strikingly, the German political scene includes a man of Turkish-Muslim origin, Cem Özdemir, as a co-chair of one of the five major political parties, the Greens, which is still an unimaginable phenomenon in Britain or France. Finally, if we consider that only about 1% of the German “citizens” are of Turkish-Muslim origin, the 0.8% share in the Bundestag seems impressively successful, especially in comparison to France, but also to Britain, where a large majority of Muslims are already citizens and yet fail to secure a representation in Parliament commensurate with their share of the citizenry. In short, provided that they have citizenship, Turkish-Muslims in Germany are likely to achieve political representation commensurate with their population.

Finally, just as the last three decades witnessed Turkish political activism spreading from the SPD to the Greens and the Left and most recently to the FDP, the next decade is likely to witness the appearance of more Turks in the ranks of the CDU, joined by a common concern for the conservation and development of moral values in modern society. This would not be surprising after all, since in both Britain and France it is possible to find candidates of Muslim origin, even if not elected, in the party lists of the right.21 Rachida Dati, who was appointed as the French justice minister by the French President Nicholas Sarkozy, is a case in point.22 Germany’s conservative CDU has included some exceptional German figures who have been sympathetic to immigrant concerns, such as Barbara John, the integration commissioner of Berlin for two decades, and Armine Laschet, the current minister for families, women, and integration in North Rhine Westphalia, the state with the largest immigrant population. It has also included, most recently, politicians of Turkish origin, including Emine Demirbüken-Wegner, who was elected to the Berlin city assembly on the CDU ticket. However, it is only after the CDU/CSU changes its attitude vis-à-vis the Turkish minority in general and Turkey’s EU membership in particular that it can hope to attract a significant share of the Turkish vote and representation. Steady naturalization and growth of the Turkish population in Germany might apply bottom-up pressures to the CDU for such a change of policy.

Endnotes

- Throughout this article, I consider all people with an immigration background from Turkey as “Turks”, regardless of whether they are ethnically Kurdish, Laz, or from another ethnic background in Turkey.

- Sener Akturk, “Redefining Ethnicity and Belonging: Persistence and Transformation in Regimes of Ethnicity in Germany, Turkey, Soviet Union, and the Russian Federation”, unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Political Science, University of California, Berkeley, 2009.

- Christian Wernicke, “The Long Road to the German Passport”, in Deniz Göktürk, David Gramling, Anton Kaes (eds.), Germany in Transit: Nation and Migration, 1955-2005 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), pp.156-159.

- My interview with Hakki Keskin, Bundestag, February 12, 2007, Berlin.

- “Almanya’da iki vekilin ‘başörtüsünü çıkarın’ çağrısına tepki yağıyor,” Zaman, October 17, 2006.

- “Almanya’da iki vekilin …,” Zaman, October 17, 2006.

- <http://electionresources.org/de/bundestag.php?election=2009&land=DE>.

- Unlike the NPD, which has its strongest showing in East German states as mentioned above, the Republicans are much stronger in West German states, and especially in the Catholic-conservative southwest, compared to East Germany. For example, the Republicans received 0.8% and 0.9% of the vote in Bavaria and Baden-Wurttemberg, respectively, twice their national average. As such we can say that the NPD is the far right party of East Germany while the Republicans are the far right party of West Germany.

- Andreas M. Wüst, “Naturalised Citizens as Voters: Behaviour and Impact”, German Politics, Vol.13, No.2, pp.351, Table 7.

- Wüst, “Naturalised Citizens as Voters…,” p.353, Figure 2.

- Joel S. Fetzer and J. Christopher Soper, Muslims and the State in Britain, France, and Germany (Cambridge University Press, 2005).

- Ahmet Kuru, “Secularism, State Policies, and Muslims in Europe: Analyzing French Exceptionalism”, Comparative Politics, Vol.41, No.1, October 2008, p.1.

- Matt Landler, “Germans Split Over a Mosque and the Role of Islam”, New York Times, July 5, 2007; and Anna Reiman, “Far-Right Mobilizes Against Cologne Mega-Mosque”, Spiegel Online International, June 19, 2007. Available online at <http://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/0,1518,489257,00.html>. Last accessed November 5, 2009.

- As of November 5, 2009, only 3 million euros were raised for the mosque. See DITIB - Türkisch-Islamische Union der Anstalt für Religion e.V. < http://www.ditib.de/>.

- Kuru, “Secularism, State Policies, and Muslims…,” p.1.

- Irka Christin-Mohr, “Islamic Instruction in Germany and Austria: A Comparison of Principles Derived from Religious Thought”, CEMOTI, No.33, Jan-June 2002.

- Recai Aksu, “Almanya’da Alevilik Din Dersleri Yayılıyor” (Alevi Religion Instruction is Spreading in Germany), Milliyet, October 11, 2008. As of October 2008, it was taught in 30 schools in these four states.

- The list of members of French parliament: <http://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/tribun/comm3.asp>. Aly Abdoulatifou, the only Muslim in this list, represents Mayotte, a predominately Muslim island that is geographically part of the Comores islands off the coast of Madagascar and Mozambique in Africa, but it is still an overseas territory of France, not part of the French mainland. The figure of 8%-10% Muslim refers to mainland France in Europe.

- Sadiq Khan (Tooting), Khalid Mahmood (Birmingham, Perry Barr), Malik, Mr Shahid Malik (Dewsbury), and Mohammad Sarwar (Glasgow Central). Sarwar, a wealthy businessman from Glasgow, was the first person of Muslim origin to enter into the British parliament in 1997.

- The list of MPs from <http://www.parliament.uk/mpslordsandoffices/mps_and_lords/party.cfm>. Accessed November 4, 2009.

- Hadi Yahmad, “‘Obamania’ Overlooking the European Parliament”, Islam Online, June 3, 2009. Last accessed in November 4, 2009.

- This is truly an unusual and exceptional appointment since there are no members of the parliament of Muslim origin representing mainland France. Dati is not a member of the parliament.