Located at the geographical intersection between East and West, with both Mediterranean and Black Sea coasts, Turkey has historically been a host country for important population movements. There were several waves of forced (ethnic) movement of populations, as a consequence of the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the following nation-building process in the region of modern day Turkey (emigration of Muslim populations from the Balkans to Anatolia and immigration of non-Muslim minority groups).

In the post-Second world war period, Turkey became a country of emigration. In 1961 a bilateral agreement on labor recruitment between Turkey and Germany was signed. In the following years, similar bilateral agreements were reached with several other European countries (Austria, Belgium, France, the Netherlands, and Sweden).

The direction of migration has reversed between Europe and Turkey. There are now more people emigrating from Germany to Turkey, than people emigrating from Turkey to Germany

Nowadays, things have changed. Turkey is still a country of emigration. But it has also become a country of immigration and transit.1 After the end of the Cold War and the breakup of the Soviet Union, immigration from the region to Turkey increased substantially. A lively cross-border movement with the countries of the former Soviet Union, but also with the Middle East countries, has occurred. And therefore, it faces similar challenges of migration and integration that are characteristic of other areas with strong cross-cultural population movements.2

Revisiting Migration of Turkey

Emigration from Turkey

In the times of the “Gastarbeiter” system of the 1960s until the early 1970s about 800.000 Turkish workers were recruited to Western Europe.3 After the economic turbulences consequent to the first oil crisis, Western European countries stopped the recruitment of non-EC-workers. However, those already working in the European Community (EC) could stay and many were even allowed the right to family reunification. Thus, the number of people with a Turkish background living in the European Union (EU) continued to increase, reaching about 2.74 million in 2008 (see Table 1).

In recent decades, there have been five main types of emigration of Turkish citizens to the EU area: “family-related emigration, asylum-seeking, irregular (undocumented or clandestine) labor emigration, contract-related (low-skilled) labor emigration, and emigration of professional and highly-skilled people.”4

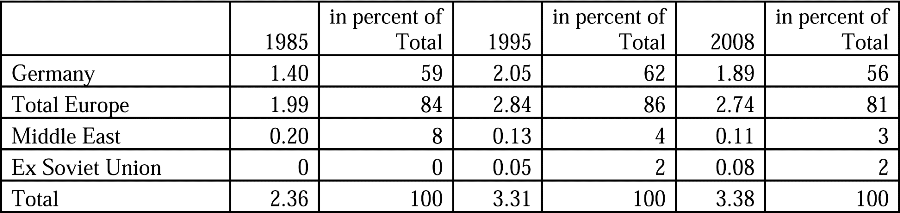

Table 1: Turkish Migrant Stock Abroad in 1985 and 2008 (in million)

Source: Ahmet İçduygu, “Turkey and International Migration,” SOPEMI Report for Turkey, 2008/09. p. 59.

According to Table 1, about 3.38 million people with a Turkish background live outside Turkey today. A 40 percent increase in comparison to 1985. The majority of Turkish migration went to Germany, where today around 1,9 million people of Turkish origin now live.While the total has not changed a lot since the mid-1990s, the geographical distribution has become different. In the mid-1990s, about 86 percent of Turks living abroad were in Europe. This share has declined to about 80 percent today.

Migration flows to Europe are down to 50-60,000 a year. The channel for this type of emigration has overwhelmingly been through family formation or family reunification. As reported by the German Federal Statistical Office (Destatis) on the basis of provisional results, 30.000 people from Turkey immigrated to Germany in 2009 and 40.000 people have left Germany with the destination of “Turkey.” Hence, the direction of migration has reversed between Europe and Turkey. There are now more people emigrating from Germany to Turkey, than people emigrating from Turkey to Germany.5

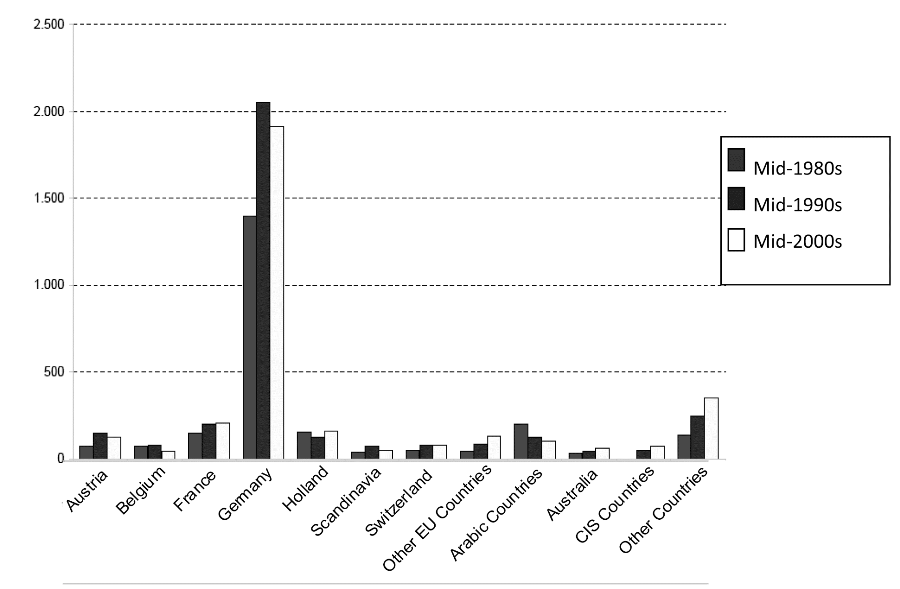

Figure 1: Where have Turkish citizens gone? Turkish Migrant Stock Abroad (in thousands)

Source: Ahmet İçduygu and Deniz Sert, “Türkei,” Focus Migration Länderprofil, No. 5, April 2009, p. 8.

An increased number of Turkish citizens have gone to the countries of the former Soviet Union. However, compared to the total, the emigration flows to close neighboring countries have remained very small. This is also true for the emigration flows from Turkey to the Middle East. Only about 3 percent of all Turkish citizens living abroad have emigrated to the Middle East.

Immigration has become more important in the last decade than ever before. In the recent decade 250.000 people per year have immigrated to Turkey

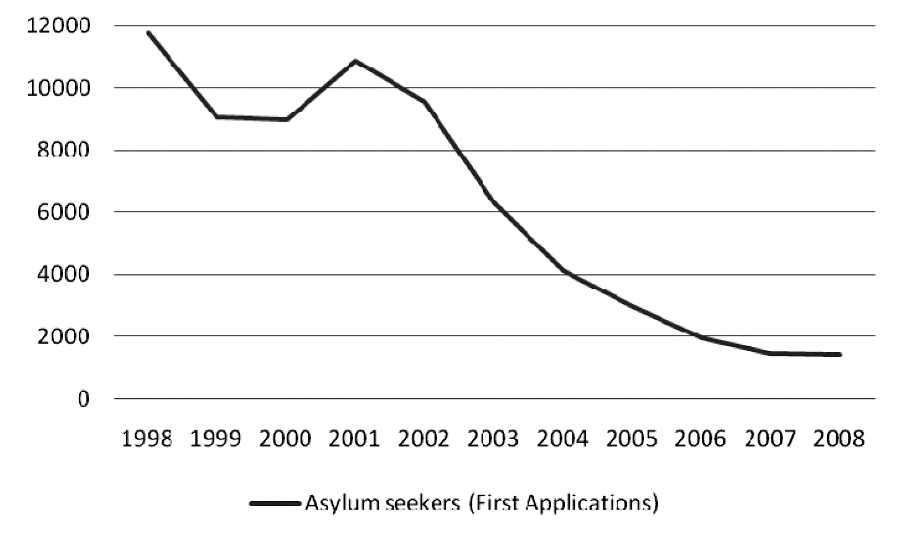

Interestingly enough, the asylum channel, heavily and controversially debated in the EU and especially in Germany in the 1990s, does not play an important role anymore. Just as an example, Figure 2 shows the strongly declining number of asylum seekers of Turkish origin to Germany in the last decade.

Figure 2: Asylum seekers of Turkish origin in Germany 1998-2008

Source: Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge (BAMF).

Immigration to Turkey

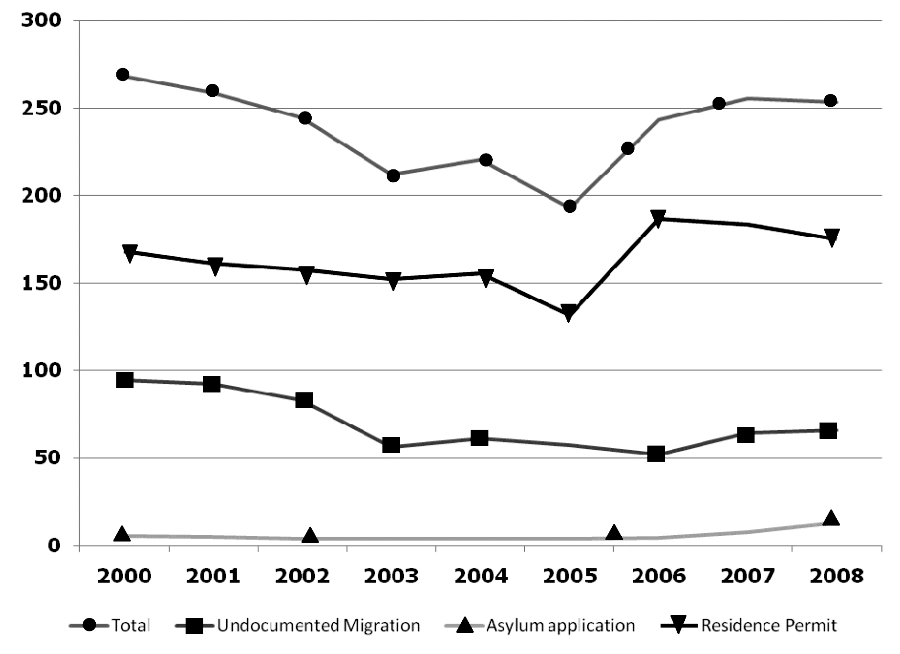

Immigration has become more important in the last decade than ever before. Figure 3 shows that in the recent decade 250.000 people per year have immigrated to Turkey. The data includes some rough estimates of undocumented immigration, including illegal immigration, visa holders who have overstayed their allotted period of stay, as well as those who have crossed the border illegally.

The number of foreign nationals living with an official residence and work permit in Turkey is relatively small (just over 170,000, see Figure 3). However, there are also citizens of countries of the former Soviet Union such as Armenia, Georgia, Moldova, the Central Asian Republics and to a lesser extent Russia and Ukraine, that come to work in Turkey often illegally in the household and tourism sectors. The Turkish visa system allows these people to commute between their home countries and their jobs in Turkey. Furthermore, there are also Turks with dual citizenship from EU countries, especially Bulgaria and Germany, that come to work in Turkey. Aditionally, to these numbers one can include students as well as retirees. Finally, about 30 percent of all migrants arrive as undocumented migrants and remain in Turkey for undetermined length of time.

Figure 3: Immigration Flows to Turkey 2000 to 2008 in Thousands

Source: Ahmet İçduygu, “Turkey and International Migration,” SOPEMI Report for Turkey, 2008/09. p. 43.

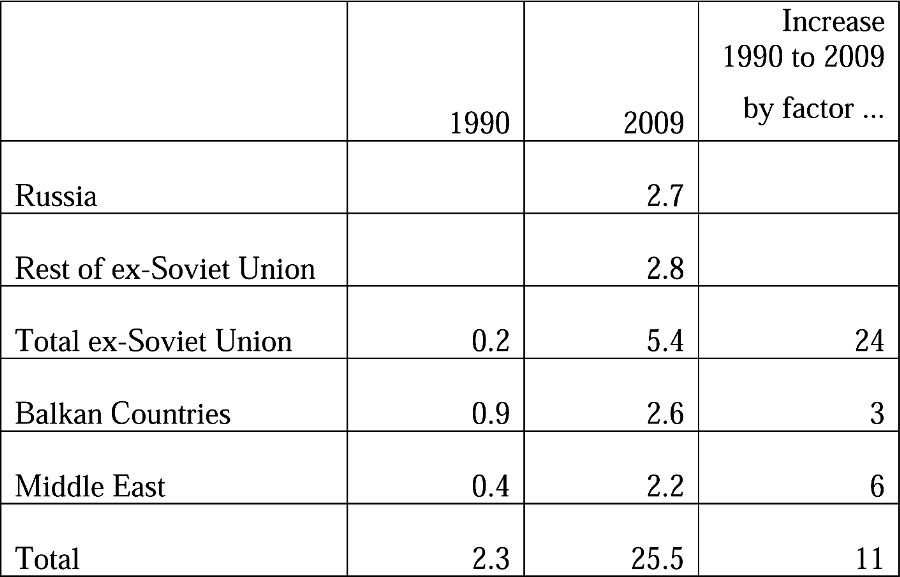

The statistics of immigration to Turkey do not really reflect the whole mobility picture. A clearer picture of the change in migration pattern’s might be assessed based on entry statistics. In 2009, 25.5 million foreigners arrived in Turkey, (see Table 2 ) more than twice the number compared to 2000 and eleven times the number of 1990.6

The largest numbers of entries continue to come from the EU member countries. Tourism is the major force behind Europeans coming to Turkey, yet short business trips from managers and staff members related to international activities of multinational firms as well as the movement of retirees and students increasingly play an important role in this trend.

Table 2: Entries of persons to Turkey, 1990 and 2009 (in millions)

Source: Kemal Kirişçi, Nathalie Tocci, and Joshua Walker, “A Neighborhood Rediscovered (Turkey’s Transatlantic Value in the Middle East).” Washington DC: German Marshall Fund of the United States (Brussels Forum Paper Series), 2010. p. 21.

Source: Kemal Kirişçi, Nathalie Tocci, and Joshua Walker, “A Neighborhood Rediscovered (Turkey’s Transatlantic Value in the Middle East).” Washington DC: German Marshall Fund of the United States (Brussels Forum Paper Series), 2010. p. 21.

Balkan Countries include Albania, Bosnia, Bulgaria, Greece, Kosovo, Macedonia, Romania, and Serbia-Montenegro. Middle East countries include Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Gulf states. Data for ex-Soviet Union for 2009 excludes Baltic States.

Entries from neighboring countries, especially from the areas of the former Soviet Union, have been steadily increasing. They have risen overproportionally by a factor of 24 between 1990 and 2009 (while the average factor for the total of all entries to Turkey was 11). Although most entries from European countries come for leisure purposes, such as holidays and tourism, there are entries of European origin that come for work from Balkans and former Soviet Union. They operate as micro-businesses (often called “suitcase businesses” in Turkey) or are employed as seasonal workers or as private households employees (cleaning, child and elderly care, gardening). Tourism has begun to play a growing role with respect to entries from Russia. With the exception of Iran, entries from the Middle East have been relatively low. But it is likely to increase in the coming years following the recent decision of the Turkish government to lift visa requirements for a number of countries from the Middle East and the Black Sea area.7

While Turkish migration to the EU has declined significantly (due to the fact that Europe has turned into a kind of “fortress”), Turkey has begun to act as a migration hub for the Black Sea area and the Middle East

In sum, Turkey has become a magnet for people from its own neighborhood. The dynamically growing Turkish economy attracts people with all kinds of qualifications and skills as well as citizens from the neighboring countries. While Turkish migration to the EU has declined significantly (due to the fact that Europe has turned into a kind of “fortress”), Turkey has begun to act as a migration hub for the Black Sea area and the Middle East. In addition, this increase of population movement into Turkey is representative of a larger picture, as Turkey often is the first transit step on the way to further destinations in Europe or elsewhere.8

Migration Balance

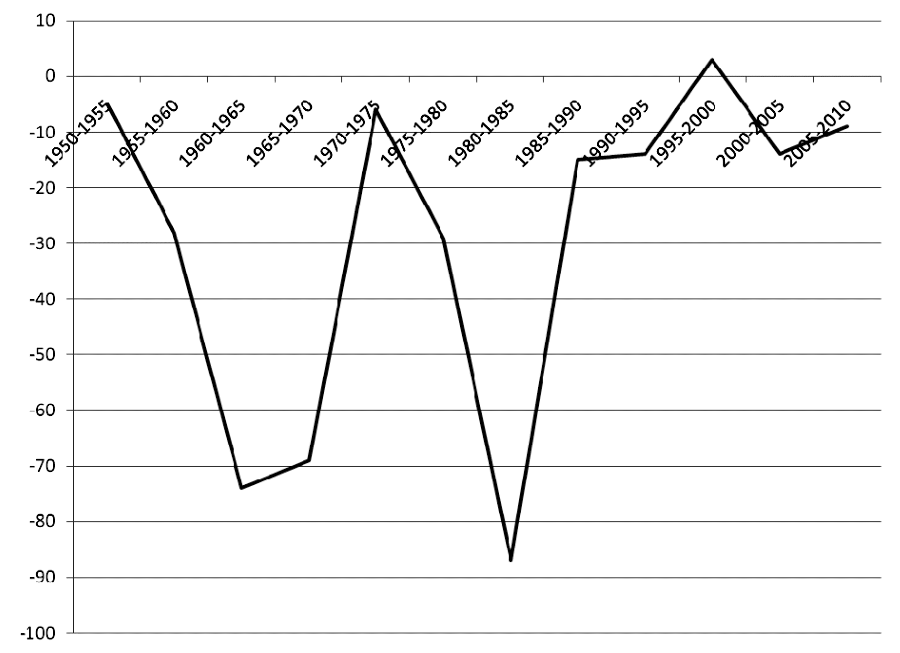

A look at the net migration (i.e immigration minus emigration) figures shows that Turkey has been a typical emigration country for decades (see Figure 4). In the past, its migration balance was negative. At the peak of emigration towards Western Europe, especially Germany, Turkey lost about 70 thousand people per year in the 1960s and in the first half of the 1980s those numbers were even higher. Today, however, emigration from and immigration to Turkey are about equal.

Figure 4: Annual Net Migration Flows (Immigration minus Emigration) for Turkey in Thousands

Source: United Nations: Population Division. Washington 2010. Retrieved January 15, 2011, from http://esa.un.org/UNPP. Annual figure is calculated as average over the period.

Source: United Nations: Population Division. Washington 2010. Retrieved January 15, 2011, from http://esa.un.org/UNPP. Annual figure is calculated as average over the period.

Envisioning a New Emigration Policy for Turkey

Emigration from Turkey: Theoretical Expectations and Empirical Considerations

What will be the potential size of Turkish emigration to the EU (especially to Germany) if Turkey accedes to the EU as a full member? The answer to this question depends on various factors such as the local, national, and global conjectures as well as economic and political conditions. Yet, this article focuses on the two main determinants that are the basis for deciding to migrate from one country to another, namely: individual behavior (i.e. the willingness to emigrate) at the micro level and the size and growth of population at the macro level.

The necessary condition for migration is whether the individual is willing to migrate. Therefore, at the micro level, it is the “individual utility function” that determines the propensity to migrate. The higher or lower the average individual migration propensity is, the higher or lower the potential for migration subsequently becomes.

Individuals compare their own utility levels (which is what they expect to achieve based on their own individual options, financial abilities, and skills) of the actual place where they reside in comparison to alternative locations. Thereby, “utility” is defined in the broadest possible way. It means basically “standard of living.” It contains economic factors (such as income, employment possibilities, purchasing power, and others) as well as non-economic factors (such as seniority, social acceptance, cultural behavior, language, and others).

A useful migration model has to include the possibility of migration flows being determined by relative deprivation (i.e. the motivation to reach a relatively better position within the social ranking of a reference group). In this perspective, the migration decision is an effective strategy to improve a person’s income position relative to others in the person’s reference group. Consequently, this is not an objective standard but a subjective standard, and will differ based on the social- economic position of the migrant and the potential for improvement in the host country.

Furthermore, migration models have to address the problematic issues that family migration poses (or a joint group of migrants and non-migrants) as opposed to individual migration. The decision to migrate is often an intra-group-interaction within a cooperative-game framework9. In this view, migration is a calculated strategic behavior that yields a higher payoff to any of the family members compared to the alternative of not migrating. Within such a framework it becomes possible to consider the issue of what risk the decision to migrate entails. By sending one of its members abroad, the family’s income is more broadly distributed. For some families, therefore, international migration becomes an optimal strategy to increase earning potential and thus reduce financial risk.

Migration models have to understand migration as a process of innovation, adaptation, and diffusion. Why are some individuals quicker to migrate than others? An answer to that question is related to the problem of risk and the possibilities of reducing it. This opens the discussion on why there are lags in the migration process. If relatives, friends or other people from the country of origin have moved to the host country in a previous period, information about the host country will flow back to the place of origin. This information will reduce the uncertainty of subsequent emigration for those remaining behind in the country of origin. So, if potential migrants have knowledge that the host country will offer them an improved quality of life, they will be quicker to migrate to those destinations. This is a potential answer to the question of why some people are more likely to emigrate than others.

Finally, migration models also have to acknowledge that immobility has an economic value. It allows people to use their specifically local know-how to earn income (i.e. mainly in the labor market) and for spending that income. This specific local know-how would be lost in the case of migration and cannot be transferred. New local know-how would have to be gained in the host country. Hence, immobility has a value in itself and explains why most people prefer to stay even if “to go” seems to be an attractive alternative at first glance. Even at second glance, most people value immobility, as it has a higher than expected net present value compared to a move abroad. Consequently, it is a very rational individual behavior to stay. The large majority of people want to live, work, and remain where they have their roots. People prefer the status quo to an unfamiliar or insecure change. The simple elimination of legal impediments to migration is usually insufficient to overcome individual (microeconomic, social, and cultural) obstacles to migration and to ignore the value of immobility.

For a macro analysis of the migration potential, individual behavior has to be transformed into an aggregated function. This is done by taking into account the proportionality of the country of origin’s population size and that of the host country; in addition to other factors such as relative economic prosperity of both countries and the capacity to absorb new migrants. The migration potential is (ceteris paribus) the larger (smaller), the larger (smaller) the population size is.

If we take the most important macroeconomic factors causing migration, we may be able to determine trends in population movements and variations of standard of living between different countries and regions. It would also help to outline expected migration patterns between Turkey and Europe in the next decades.

In the mid-2000s, the population was 82 million in Germany and 70 million in Turkey. Throughout the same period, the population grew by 0.1 in Germany and by 1.5 in Turkey. However, Turkey’s current fertility rate and population growth rates are in decline. Also, in comparison to Germany, Turkey’s population is increasing however this trend will be stabilized in the long run.

In Turkey, the population development might lead to an excess supply of labor while in Germany it might lead to an excess demand for labor. Taken together that will stimulate incentives to migrate from Turkey to Germany.

The EU’s demographic trend is characterized by an ageing problem, low fertility rates, and a decline in the active population – (i.e.: the population of working age). In the mid-2000s, 20 percent of the total population in Germany was over 65 years of age. In Turkey, this ratio remained only at 6 percent. Thus, the youth of Turkey’s population could offset the ageing problem of EU societies in the near future.

Another crucial factor in determining the causes of migration is the contrast in the average standard of living among different countries. Choice of individuals to emigrate based on their increased income earning potentials does not follow a linear function, but instead a logarithmic. This means that there is a stronger propensity for an individual to choose to migrate in the case of larger income gaps, which becomes weaker in the case of smaller income gaps. The propensity for an individual to emigrate may occur long before income generation between the host country and the country of origin have equalized because of a saturation point of migration. Thus, the speed of change is important. It makes a big difference whether the income gap is declining rapidly or not.

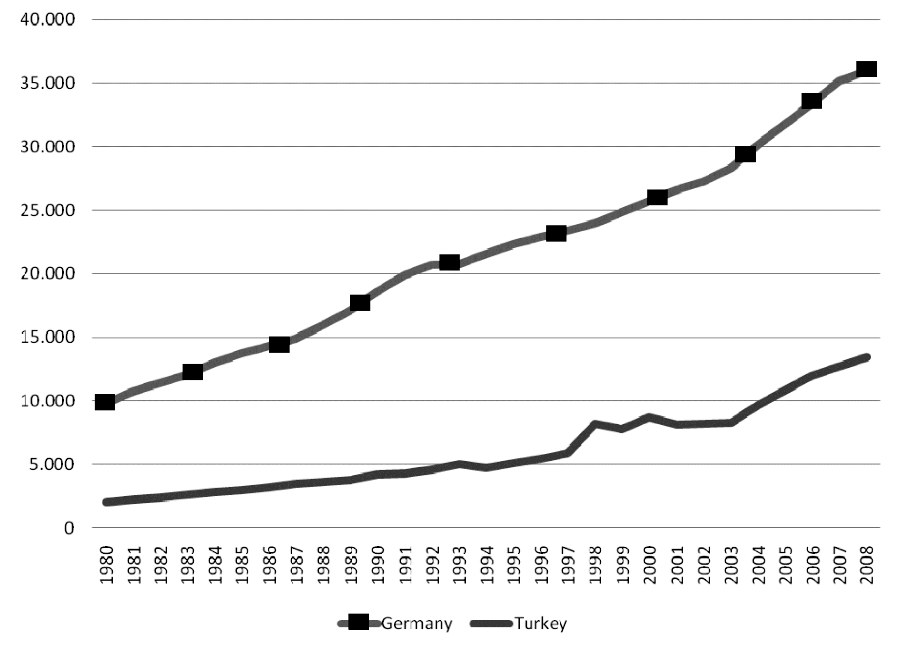

Figure 5 shows the rather wide gap in the average standard of living between Turkey and Germany by comparing the per capita GDP measured in purchasing power parities US-$. The gap has declined. In 1980 the GDP per capita in Turkey reached about 20 percent of the German GDP per capita. Today, it reaches about 37 percent.

Figure 5: Per Capita GDP (in Purchasing Power Parities US-$)* in Turkey and Germany, 1980 to 2008

Data Source: World Bank: World Development Indicators.

* In this figure Purchasing Power Parity US-$ have been used to reflect the standard of living and its difference between Turkey and Germany.

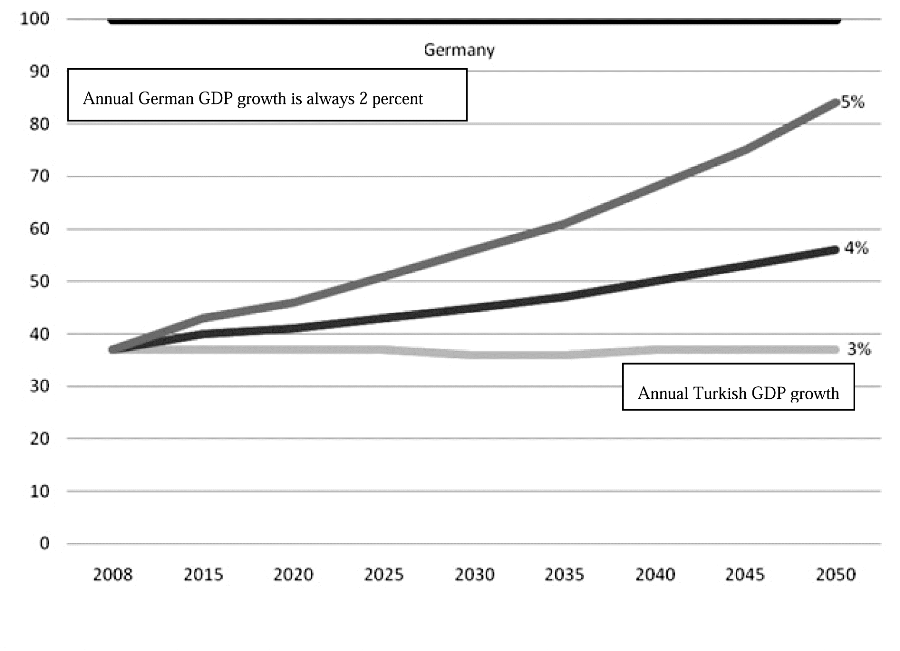

To illustrate how long it may take to catch up, Figure 6 reflects a simple simulation exercise. It is assumed that in the next decades Turkey’s GDP will grow faster than Germany’s GDP. (In the mid-2000s, the GDP per capita was 30.000 Euro in Germany and 6.500 Euro in Turkey).

The simulation shows that under this assumption, the German GDP grows with a constant rate of 2 percent per year while the Turkish GDP has to grow by 3 percent per year to keep the existing gap of the GDP per capita vis-à-vis Germany stable. Turkey requires a more rapid growth of its GDP to compensate for its more rapid population growth. If the Turkish economy grows by 4 percent per year and the German GDP stays at 2 percent per year, the Turkish GDP per capita will reach half the size of the German GDP per capita by 2040. If it grows by 5 percent per year, the 2:1 gap is reached by 2025. The simulation exercise is simply to illustrate how long the substantial gap of the average standard of living will persist between Germany and Turkey. This would be the case even if the Turkish economy grows (much) faster than the German one.

Figure 6: Simulation of the Gap in Per Capita GDP (in Purchasing Power Parities US-$)* between Turkey and Germany, 2008 to 2050 under the assumption of different annual growth rates for the GDP

Data Source: World Bank: World Development Indicators.

* In this figure Purchasing Power Parity US-$ have been used to reflect the standard of living and its difference between Turkey and Germany.

A strong potential for emigration from Turkey to the EU will remain as long as Turkey continues to have a fast growing population, while the EU has a declining and aging population. In addition, the gap between the average standard of living in the EU and Turkey is also a significant factor. This continuing pattern of emigration from Turkey to the EU, in particular Germany and Austria, may be one of the key reasons why the process of Turkey’s admission to the EU has been stalled by certain European countries. They are concerned about applying the right of free movement of labor in the case of Turkish workers. Are these fears justified by theoretical expectations or empirical evidence?

As it is briefly summarized in Box 1, several econometric studies have attempted to estimate the potential for migration from Turkey to the EU. They can be categorized into two groups. One group of studies has used surveys and has evaluated these surveys to conclude on the future trends in migration. Another group of studies has applied econometrical methods to forecast the potential for migration.

While polls and surveys are very popular, they are not very reliable in forecasting the potential for migration. “The intention to migrate” is a complicated concept, which is fairly complex to measure. Due to the subjectivity of the concept and its sensitivity to time, most of the surveys suffer from the absence of clear definitions. One of the main drawbacks of opinion polls and individual surveys is the biased impact of the questionnaire on the flow of answers. Hence, especially when it comes to surveys, the distinction between the “intention” and “act” itself must be clearly underlined. Estimates that depend on opinion pools are used to forecast the amount of expected migration flows.

Econometric models use several approaches to estimate the amount of potential migration. Error correction models test for the equilibrium in the long run in which part of the population has the potential to migrate. Gravity models analyze annual migration potential via various explanatory variables such as stock of existing migrants in the country, income discrepancies, unemployment, and rate differentials etc. Based on earlier migration experiences, extrapolation models are constructed for the purpose of forecasting future trends.

The main methodological difficulty for all of these approaches lies in the fundamental political and institutional change that goes along with possible Turkish accession to the EU. Turkey becoming a member of the EU and being granted the right of free movement for Turkish workers means doubtlessly a unique experience with no historical blue print at all. Thus, if there is a case where the famous Lucas-critique is well applied, it comes with the changes an EU membership for Turkey would generate.10 There are two key questions. First, to what extent can we learn from past patterns to determine future outcomes? And two, how much we can speculate as to the extent of future migration flows from Turkey to the EU when the admission of Turkey to the EU will bring about such fundamental changes; such as going from a system of severe restrictions of the flow of labor to the free movement of labor.

Based on the summary of the existing empirical evidence garnered from all the different studies indicated in Box 1, one thing becomes very clear: The estimates present broadly varying numbers. Figures with respect to volume of potential Turkish migrants from Turkey to the EU range between 0.5 to 4.4 million. It is sufficient to say that there is a lack of agreement on a reasonable interval with a minimum and a maximum value. The range is extensive and it depends on the data sets and methodologies applied. This leads us to question the reliability of numbers obtained.

Box 1: Survey of Different Empirical Studies Estimating the Migration Potential from Turkey to the EU under Free Migration Conditions.

Sübide Togan11 makes a forecast of Turkish migration to Germany under free migration conditions. He concludes that the Turkish immigrant population, which started out at about 2.2 million in 2000 would reach about 3.5 million in 2030, under the assumption of zero restrictions on migration. His findings are confirmed by Harry Flam12.

Arhah M. Lejour, Ruud A. de Mooij and Clem H. Capel13 expect that 2.7 million people will permanently move from Turkey to the EU in the long term. The majority of these people will settle in Germany, where Turks have settled in the past.

Refik Erzan, Umut Kuzubaş and Nilüfer Yıldız14 estimate that net migration from Turkey to the EU-15 over the period 2004-2030 is between 1 and 1.2 million foreseeing a successful accession period with high growth and free mobility starting 2015. According to another scenario under the low growth rates accompanied by non-free movement, emigration flows from Turkey in 2030 will exceed 2.7 million.

By far the highest figure is mentioned by the Osteuropa-Institut in Munich (Quassier), which forecasts (in the absence of transition periods and with full application of free movement from 2013), the long term potential migration from Turkey to Germany will be 4.4 million on the basis of the existing number of Turkish migrant workers as well economic differentials at that date.15

Hubert Krieger and Bertrand Maitre16 predict, assuming a Turkish population stock of all inhabitants of 15 years and older of nearly 48.9 million in 2003, a migration potential of 3.03 million for the general intention and 0.15 million for the firm intention. Using the “basic intention to migrate” criteria, it is predicted that minimum 400.000 Turkish citizens will migrate to EU15 over five years, with a possible accession after 2015.

Forecasting the approximate volume of the potential for migration is a necessary exercise, especially for policy makers. However, such controversial studies are not sufficient. The results of these studies should be approached with a dose of caution and skepticism because the numbers range widely, the quality of the data is poor, and the methodologies applied are unclear and inconsistent. Moreover, the focus of the debate would be more informative and salient to policy makers if it shifted to issues such as the profile of the migrant population, the structure and the dynamics of migratory patterns, the regional distribution of the outflows, the trends and mechanisms behind future potential migration movements, and finally the motivation and triggers spurring migration towards Europe.

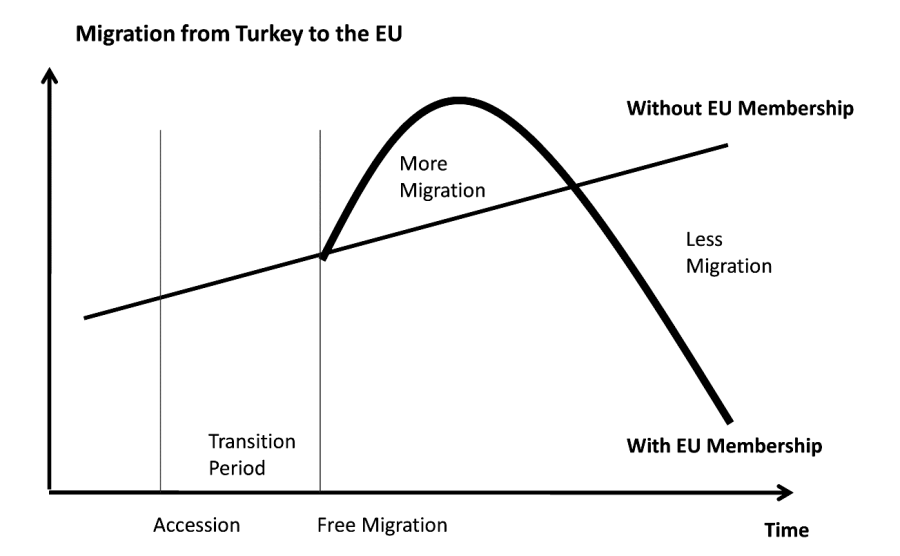

Actually, the question is not: how many Turkish workers would use the right to move freely. The right question is: how many more (or even less) would move compared to a situation with no right of free movement. Erzan et al17 show that if Turkey’s membership process is endangered and a high economic growth cannot be sustained in Turkey, 2.7 million people may seek to emigrate to the EU-15, despite the restrictions on labor mobility. This is even more than in a scenario where Turkey obtains full EU membership and free movement for Turkish workers. Thus, it is not unrealistic to expect, that without full EU membership and free movement of labor, Turkish migration flows towards the EU will reach higher levels. The migration experience after the EU’s opening towards Eastern European countries of the former Soviet block showed that the actual migration flows can be fairly below expected levels, following accession. It might be that something like a migration “hump” will be the most realistic scenario (See Figure 7). There will be an initial increase of migration flows, immediately after the right of free movement is granted. But after a while, it will subside.

Figure 7: The Migration Hump

Source: Martin Philip, Trade and Migration: NAFTA and Agriculture (Washington: Institute for International Economics, 1993), p. 136.

Source: Martin Philip, Trade and Migration: NAFTA and Agriculture (Washington: Institute for International Economics, 1993), p. 136.

What we have learnt from the EU experience in the past is that if labor has the legal right to move freely, this makes people (especially in border areas) more mobile internationally, but it does not in itself induce mass migration from one country to another. People’s social and cultural ties to their local environment are an important obstacle to migration, which has commonly been underestimated from the perspective of theoretical economics and has not been taken into account seriously enough by the structural migration (forecasting) models.

On the macroeconomic level, international labor migration within the common EU labor market has proved to be mainly demand-determined: it usually depends to a major extent on the needs and employment opportunities in the immigration countries. In the EU, trade has reacted much faster and more elastically to economic integration than labor. The removal of formal and informal protectionist impediments led to a strong increase in intra-community trade. The equalization of goods and factor prices expected by arguments of the international economic theory thus materialized through trade rather than through the increased mobility of labor. To an important degree, trade has replaced the economic demand for migration in the EU. In brief: having the option to migrate within a common labor market has turned out to be the most effective anti-migration policy.

Immigration to Turkey

Turkey is an important actor in terms of migration flows due to its geopolitical significance and closeness both to the EU area and MENA (Middle East and North Africa). The possible accession of Turkey to the EU triggered the discussion on migration potentials from Turkey as it stands at the nexus of emigration, immigration, and transit migration.

Immigration from the EU to Turkey

The migration flows from the EU to Turkey will be determined by different factors in the future:

- European retirees will keep migrating to Turkey, particularly to the Aegean and Mediterranean Area, for their retirement life.18

- The return of emigrants to Europe of Turkish origin as well as retiring Turkish migrants (e.g. first generation German-Turks) will also be an increasing part of potential migration flows from the EU back to Turkey. Yet, due to the visa regulations (each individual that carries a valid visa should enter the host country every six months in order to keep the residency visas valid) ; their movements will be categorized as “circular migration.”

- As Istanbul becomes more and more attractive for international business, multinational corporations will continue to set up their headquarters there. Subsequently, this will motivate expatriate workers and professionals to migrate to Turkey for work related purposes.

In addition to foreign professionals, the potential migration of highly-skilled migrants (who are educated in Germany) with Turkish background to Turkey will be significant. Yaşar Aydın 19 in his study analyzing the return migration trend back to Turkey of highly-skilled migrants of Turkish origin, who went through the German education system (from primary school until the college degree), discusses whether this potential migration is a brain drain process, within the “transnationality framework.” In addition analyzing the estimated amount of potential migration from Turkey to the EU, Aydın20 postulates the reasons motivating highly-qualified migrants of Turkish origin to go back on their initial decision to migrate. Among these reasons, the three most important ones are as follows. First, due to the recent developments in the German economy, such as privatizations, increasing unemployment, and shrinkage of social benefits, highly-skilled labor is under the risk of unemployment or underemployment. These economic determinants are among the key factors that influence the confidence of highly-skilled workers in the future of the German economy. Second, highly-qualified workers feel that they run the risk of being at a disadvantage or even discriminated against. For instance, the unemployment rate among the German academics is 4.4 percent, whereas it is 12.5 percent among the academics of immigrant background. Third, in line with the integration of the Turkish economy with the world economy, the Turkish labor market became quite attractive for many highly-skilled German-Turks. The attractiveness of Istanbul, as it is a business or corporate center for many German firms is now preferred over European branches due to social networks and cultural closeness. This in itself also plays a role in return migration decisions. German companies that have branches in Istanbul often prefer highly-qualified German-Turks, who immigrated back to Turkey, hold a blue-card (free to work and reside in both countries), and speak both languages.

It is possible to foresee that illegal migration from the Middle East will remain an issue in the near future - and may even increase due to the latest developments in Turkey’s liberal visa policy

4. Student migration will play a crucial role as well. Because of a common language and a shared cultural heritage, students from the Turkic Republics will opt to come to study in Turkey for their education. This potential for Turkey to temporarily host future students may turn into permanent migration depending on work opportunities once they complete their studies. The Green Card application of 2000 and the Immigration Act of 2005 in Germany, which intended to encourage highly-skilled migration to Germany, provide us with some insights into the future trends of migration policies and tendencies. For instance, according to Heinz Werner,21 the regulation of the Green Card was applied to foreigners who graduated from German universities and polytechnics. Before the implementation of the Green Card, this same group of students had to leave the country after graduation. This change represents the policy intent behind the Green Card, which is to recruit students who are perceived as assets for the future of Germany’s highly-skilled and professional labor force. The ease at which students obtain residency and work permits in the aftermath of their internship process can also be considered as a policy that encourages student migration in the short run, and in the long run, they will be integrated into the highly skilled labor supply.

Immigration from the Middle East to Turkey

Currently, Turkey altered its approach with respect to its own immigration policy, namely: asylum law, visa regulations, illegal migration, and human trafficking. The two main legislations that are under consideration in the area of asylum law are: (1) the 1994 Asylum Regulation, and (2) the 2006 Circular - stipulating asylum procedures and the rights and obligations of refugees and asylum seekers. Even if Turkey is party to the UN Refugees Convention of 1951, it still has not lifted an important geographical limitation, namely that non-Europeans are not granted refugee status. With respect to visa restrictions, since 2005, Turkey is following a liberal visa policy, in which several visa-free agreements were signed with neighboring countries, including: Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, and Russia. The main motivation for Turkey is mainly economic gain from increased integration in the region. Yet, its liberal visa regime brought about a discussion on the ‘construction of a new Schengen area in the Middle East. In line with the EU regulations, Turkey became more proactive in dealing with illegal migration and human trafficking. These recent developments in Turkey’s immigration management triggered discussions of a possible Middle Eastern Union. In this alternative model, Turkey would have the leading role.

Under this framework, it is possible to foresee that illegal migration from the Middle East will remain an issue in the near future - and may even increase due to the latest developments in Turkey’s liberal visa policy. Male migrants will be motivated by job opportunities in construction, tourism, and entertainment - whereas female migrants will often be chosen for domestic services. Labor migration, contract-dependent migration, and marriage migration will be persistent in the near future. However, asylum based migration may decline with Turkey’s full membership to the EU and the potential progress and resolution of the Kurdish issue. There is currently little potential for emigration from Turkey to other Middle Eastern countries22, as many Middle Eastern countries suffer from a poor economy, chronic underemployment, and see a good deal of their own young, qualified and semi-qualified work force have to emigrate to Europe to find jobs or work in the Gulf.

Conclusions

Having become a country of immigration and transit migration, Turkey faces similar challenges of migration and integration that are characteristic of other areas with strong cross-cultural population movements.23

If Turkey accedes to the EU, the Turkish migrant groups, which are the most likely to emigrate to Europe, are those that already have networks in place in Europe and relatives who are already settled there. The number of student migrants (which is already high because of exchange programs) will have a tendency to increase since students tend to integrate more easily because they are younger and they are not confronted with insurmountable language obstacles. With respect to labor migration, migration will take place at every skill level. Emigration and also return migration of highly-skilled Turkish workers from Europe to Turkey will become more significant. Asylum emigration of ethnic groups, which have historically suffered discrimination, may be decreasing because of new EU regulations which will protect their rights within the country of origin. Turkey is now abiding by these stricter EU rules and an increase respect of human rights and cultural rights. Finally, circular migration will be a new form of immigration flow due to freer mobility.

These arguments create expectations for rather strong migration flows. However, there are some other factors that moderate at least partly these expectations. Along with being integrated in the EU, stronger economic growth will substantially improve the average standard of living in Turkey. The removal of obstacles to trade and the integration of international finance markets make trade in goods and services easier. It makes capital and know-how more mobile internationally. Labor migration, thus, becomes increasingly dependent on the progressive liberalization of trade in goods and services and the international mobility of capital.

However, the improvement of the level of the standard of living is not the only factor that influences an individual’s decision to migrate. If people expect that life is going to be better in their home country and that at least their children will have better options they might stay even if they could improve their standard of living by emigrating.

Push and pull factors behind the potential migration are of great importance. With the possible membership to the EU, Turkey should consider looking at these factors in their historical context to find policy solutions to eliminate the pushing factors and improve the pulling ones. As low wages and high unemployment as the main “pushing factors” behind the potential for labor migration, Turkey can develop policy measures to deal with these issues. This, inevitably, requires structural and institutional reforms that also lead to the stabilization of the Turkish economy. Improved living standards, which are closer to the EU average, would decrease the motivation of Turks to migrate towards Europe. This would be a “pulling” factor. EU membership will help to reach this goal. Therefore, EU membership might not provoke more but rather less migration from Turkey to the EU.

One of the most crucial challenges for Turkey in its relations with the EU is illegal migration. Due to its geographical location, Turkey will be under the risk of increasing irregular migration pressure. Kemal Kirişçi 24 emphasizes the increasing importance of managing illegal migration, both as a challenge and as an opportunity, for Turkey in the near future as it has become a transit country. Yet, he postulates that the manner in which “migration” has become securitized by the EU has adversely affected the EU-Turkish relations and generated “mistrust” on both sides. According to Kirişçi 25, the EU feels that Turkey is not doing enough to combat and prevent illegal transit migration and suspects that Turkey has allowed illegal migrants to use its territory to transit to the EU; and there is fear on the Turkish side that the EU intends to use Turkey as a buffer zone for irregular migrants. In his work estimating the impact of the global crisis on the illegal migration and remittances, Erzan26 presents predictions - under different employment and GDP growth rates - that are ambiguous due to the fact that growth in the EU will likely be affected more severely than the peripheral countries.

If it is well managed, the challenge of illegal migration can turn into an opportunity for Turkey to reinvigorate negotiations with the EU. Cooperation and dialogue between Turkey and the EU with respect to illegal migration could have increased security benefits both sides.

The EU intends to control migration, select migrants on a skills-basis, avoid illegal migration, and sign bilateral agreements so as to match market and employer needs with the migrant labor supply.

Turkey, which has been striving a long time to accede to the EU, has recently altered its foreign policy and migration management to improve its relations with its neighbors, especially in the Middle East. This change represents both a challenge and an opportunity for Turkey in its future management of its migration policies. On the one hand, it can be read as a ‘political message’ to the EU, which recently presented this privileged membership as an alternative for Turkey, revealing that there are other options for Turkey in its neighborhood for various integration possibilities and unions. On the other hand, within the EU, Turkey’s liberal visa policy has increased concerns around security issues in relation to border management, since the free entrance of immigrants both from the Middle East and from Russia facilitates the potential for illegal and transit migration to Europe via Turkey.

Endnotes

- Transatlantic Academy, “Getting to Zero: Turkey, its Neighbors and the West,” www.transatlanticacademy.org, Washington DC, (June, 2010), retrieved December 15, 2010, from http://www.

transatlanticacademy.org/ sites/default/files/Getting% 20to%20Zero_0.pdf; Ahmet İç-duygu and Deniz Sert, “Türkei,”Focus Migration Länderprofil, No.5, (April, 2009), retrieved June 20, 2010, from http://www.focus-migration.de/ Tuerkei_Update_04_2.6026.0. html. - Juliette Tolay, “Turkey’s Other Multicultural Debate: Lessons for the EU.” Annual Sakıp Sabancı International Research Award Winning Lecture. Istanbul, June 2010 (mimeo).

- Still the best analysis of the Guest Worker Program is: Philip L. Martin, The Unfinished Story: Turkish Labour Migration to Western Europe, with Special Reference to the Federal Republic of Germany. (Geneva: ILO., 1991); for a more recent and more general analysis of the Guest Worker System see Philip L. Martin, Managing Labor Migration in the Twenty-first Century. (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2006).

- Ahmet İçduygu, “Turkey and International Migration,” SOPEMI Report for Turkey, 2008/09, p. 9.

- German Federal Statistical Office (Destatis): Press release (No.185 / 2010-05-26; Wiesbaden). Levelof immigration into Germany increasing again in 2009. The data include German pensioners (“snow birds”) and also the return of Germans with Turkish background to their country of birth (i.e. Turkey). Thus, the change in the stock of people with a Turkish background living in Germany might not correspond to these flow data.

- These figures contain back-and forth movements, several entries and commuting.

- Kemal Kirişçi, Nathalie Tocci, and Joshua Walker, “A Neighborhood Rediscovered (Turkey’s Transatlantic Value in the Middle East),” Brussels Forum Paper Series. 2010.Washington DC: German Marshall Fund of the United States .

- Refik Erzan, “The Impact of the Global Crisis on Illegal Migration and Remittances: The Turkish Corridor,” CARIM Analytic and Synthetic Notes, 2009/38. Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, Fiesole/Florence (EUI) and Kemal Kirişçi, “Managing Irregular Migration in Turkey: A Political-Bureaucratic Perspective.”CARIM Analytic and Synthetic Notes, 2008/61.,Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, Fiesole/Florence (EUI).

- This concept belongs to game theory and means that the game is between groups of players who are in coalition. Since the game is not between individual players, decisions are made in coordination.

- The Lucas-critique is “that any change in policy will systematically alter the structure of econometric models. ... (This conclusion) is fundamental; for it implies that comparisons of the effects of alternative policy rules using current macro econometric models are invalid regardless of the performance of these models over the sample period or in ex ante short-term forecasting”. Robert E. Lucas, “Econometric Policy Evaluation: A Critique,” Karl Brunner and Allan H. Meltzer (eds.), Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, Vol. 1, (1976), p. 41. The Lucas-critique refers to the level of consistency and invariance over time and space. It is about the correctness of an extrapolation from past migration patterns to expected migration behaviour and it is about the possibilities of applying empirical migration experiences from one area to another. Some scholars try to overcome this fundamental methodological problem by the inclusion of so-called country-specific effects. In most econometric forecasts the country-specific aspects are captured by a country-specific intercept which remains constant over time. However, it remains more than crucial how the country-specific intercept is defined and applied to Turkey that has had no historical experience of free migration to Europe.

- Sübide Togan, “Turkey: Toward EU Accession,” World Economy, Vol. 27, No.7 (2004), pp. 1013-1045.

- Harry Flam, “Turkey and the EU: Politics and Economics of Accession,”CESIFO Working Paper, No. 893. (2003).

- Arhah M. Lejour, Ruud A. de Mooij and Clem H. Capel, “Assessing the Economic Implications of Turkish Accession to the EU.” CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis, No 56. (2004).

- Refik Erzan, Umut Kuzubaş and Nilüfer Yıldız, “Immigration Scenarios: Turkey-EU,” Turkish Studies, Vol. 7. No. 1 (2006), pp. 33-44.

- Commission of the European Communities: Issues Arising from Turkey’s Membership Perspective (Commission Staff Working Document, Brussels SEC (2004), 1202, p.19.

- Hubert Krieger and Bertrand Maitre, “Migration Trends in an Enlarging European Union.” Turkish Studies. Vol. 7, No.1 (2006), pp. 45-66.

- Erzan et al, “Immigration Scenarios:Turkey…,” pp.

- Only in Alanya, the total number of Germans and Dutch is 5000-7000 (Ahmet İçduygu, “Turkey and International Migration,” SOPEMI Report for Turkey, 2008/09).

- Yaşar Aydın, “ Der Diskurs um die Abwanderung Hochqualifizierter turkischer Herkunft in die Turkei,” HWWI Policy Paper, 3-9, Hamburg, 2010.

- Aydın, “Der Diskurs um die Abwanderung…,” p. 10, 11.

- Heinz Werner, “The Current “Green Card” Initiative for Foreign IT Specialist In Germany-International Mobility of The Highly Skilled, OECD Proceedings, 2002, pp. 321-326.

- Egypt, Lebanon and Jordan are skilled and high-skilled labor exporting countries, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Libya, United Arab Emirates are large scale labor importing (high skilled) countries, Algeria is an unskilled labor exporting country and Tunisia, Syria, Iraq, Morocco are self-sufficient countries which are neither importing nor exporting labor power.

- Juliette Tolay, “Turkey’s Other Multicultural Debate: Lessons for the EU.” Annual Sakıp Sabancı International Research Award Winning Lecture. Istanbul, June 2010 (mimeo).

- Kirişçi, “Managing Irregular Migration …,” p. 1, 2.

- Ibid, p.1.

- Erzan, “The Impact of the Global …,” p. 17.