Among the several challenges caused by immigration to nation-states, the issues of citizenship and integration stand out as some of the most important. Increasing active civic participation is of crucial value for the democratic development of contemporary Europe. Whether we focus on the individual and the value of face-to-face contact or we focus on the role of the organization as a state-citizen mediating institution in strengthening democracy, both types of engagement have an effect on the processes of integrating immigrants into the host society. Participation in civil society through voluntarily organizations and associations can thus be considered a key factor for the functioning of civil society.

Furthermore, organizational engagement can be a vehicle for active citizenship and may lead to resistance towards constraining notions of national identity, integration and excluding structures as it can create a platform for new types of claims making and identity positions.

Organizational activities do not take place in a vacuum but are situated in a particular structural framework and context. Lise Togeby argued that it is the political institutions of the host country (and the model of inclusion) rather than its cultural traditions that are decisive for immigrant behavior and civic engagement.1

The organizational language of the host state will reflect the organizational patterns of immigrants in the given state

An often-mentioned example is Soysal’s analysis of different Western European incorporation regimes.2 She sees these models (corporatist, statist and liberal) as providing a framework for incorporation: “Turks in Sweden are organized differently than Turks in France or Switzerland”3, she claims and further states that:

Migrant organizations, in turn, define their goals, strategies, functions, and level of operation in relation to the existing policies and resources of the host state. They advance demands and set agendas vis-à-vis state policy and discourses in order to seize institutional opportunities and further their claims. In that sense, the expression and organization of migrant collective identity are framed by the institutionalized forms of the state’s incorporation regime.4

Both earlier and later research has come to the same conclusions: the organizational language of the host state will reflect the organizational patterns of immigrants in the given state. In the article I take this theoretical discussion as my backdrop for understanding the Turkish organizing processes in a Danish context and look first at the institutional arrangements and integration and the citizenship model prevailing in Denmark, and secondly at the collective Turkish organizing processes within this structural framework and at the dynamics of social participation and agency. Before beginning the discussion, I begin with an overview of the demographics of the Turkish migration to Denmark in order to contextualize the discussion. The material for this article consists of policy documents, documentation from Turkish organizations and interviews that were conducted while writing my PhD thesis.5 The Danish case consisted of 22 interviews with members of Turkish organizations and an analysis of documentation from 33 organizations. All interviews were conducted in Danish. Most of the organizations were receptive towards the study, although religious organizations were more difficult to establish contact with. Most of the informants can be characterized as young, which probably explains why language did not provide a barrier. This would most likely not have been the case if the informants had been older. The dissertation also includes the cases of Sweden and Germany. The study in Sweden followed a similar data collecting process whereas the German case necessitated the use of interpreter.

Before beginning the analysis, it is necessary to clarify the category ‘Turkish’. When referring to Turks I regard the term Turks as a general category of people within/from Turkey, which includes Kurds, Alevis and other regional self-identifications such. Likewise, I include persons born in the host country with Turkish parents. The category of Turk expresses the most common self-identification among my respondents – when people identify themselves as Kurdish or Alevi it will be mentioned explicitly. The same regards the typology of organizations. Thus, the term is used from a pragmatic perspective to make the text more readable instead of making all possible reservations every time members from the different Turkish and Kurdish communities are mentioned.

Turkish Migration to Denmark: The Demographic Profile

In Denmark the Turks amount to close to 58,200 immigrants and descendants, which account for 12% of all foreigners in the country and makes it the largest minority group in the country.6 Turks started arriving in Denmark in the early 1970s as part of the guest-worker program, but contrary to popular belief, the actual program only existed for two months in the autumn of 1973 when 2,485 and 2,000 persons were given work permits, while in the previous years there was no regulation and control. In November 1973, the guest-worker program was suspended due to the economic recession following the first oil crisis. By that time 6,173 people with Turkish origin were living in Denmark. Although the official end to immigration has been upheld since (with some exceptions), several people have been given access to the country mainly via family reunification. Turkish migrant workers have hence brought their families to the country, and later their children have to different degrees maintained the ties to the home country by finding spouses from back home. The rules for reunification have been tightened considerably over the years, but nonetheless people still arrive legally from the traditional guest-worker countries, although in limited numbers. Besides these flows Denmark has accepted a small number of political refugees from Turkey seeking political asylum. From 2000 to 2005, Denmark received 112 applications of which nine were granted.7 All of these were Kurdish political activists, as were the majority of previous asylum seekers.

While the first generation of Turkish migrants are now going into retirement and a fairly large share became marginalized on the labor market years ago, the descendants — and especially the females — are on a general level showing large upward mobility when it comes to labor market participation and educational achievements. Taking the 25-29 age group as an example, the employment rate for native Danes is 84% for males and 79% for females. Among the Turkish migrants (i.e. people having entered via family formation schemes, etc.) 73% of the males were in employment compared to only 44% of the females; however, among the descendants in the same age group the levels were 70% for male descendants and 67% for females.8 Looking at the naturalization rates, persons with Turkish origin constituted the largest numerical group acquiring Danish citizenship in 2006. Of the immigrants 47% have been naturalized while 64% of the descendents have been.9

The Danish immigration policy since the mid-1980s has developed from being a labor market-regulative policy influenced by economics to focus primarily on aspects of socio-economic integration

Turks are a present part of Danish society and live all across the country although most live in urban areas. The majority, roughly 70%, live in council housing.10 These residential patterns have spurred the ongoing debates on segregation (in Danish the term is ‘ghettoization’) and called for action to ‘normalize’ the population. The terms ghetto or parallel society are deeply problematic as we talk about extremely diverse neighborhoods with more than 80 national groups represented but ‘Danes’ are a minority in these areas which legitimizes such notions no matter the prevailing diversity. However, nowhere in Denmark are there areas resembling Kreuzberg/Neukölln in Berlin or North Brabant in Rotterdam with their highly visible Turkish everyday life in streets and commercial venues. Vesterbro and in particular Istedgade in the heart of Copenhagen and some parts of Nørrebro likewise in Copenhagen do have many Turkish shops and restaurants bearing names such as “Little Konya” or “Istanbul” as well as visible Turkish social clubs; nonetheless, it is a very limited mark on the urban environment compared to elsewhere in Europe.

Categorizing this minority groups as ‘Turks’ is also somewhat generalizing as this group in reality comprises people with different ethnic origins such as Kurds, Alevis and other regional self-identifications including Circassians, Laz and Assyrians. Ethnic boundaries are only one division however. There are several other divisions within the Turkish minority group: ethno-political between Turks and Kurds; political between nationalistic right-wing and left-wing groups; religious between Sunnis and Alevis and between a secular Turkish state and religious communities abroad (for example, the Diyanet vis-à-vis the Milli Görüş). Furthermore, there is a variety of party political fractions that also are active outside Turkey, which opens up for the transnational perspective. Finally, the ongoing discussions and speculations about the possible Turkish membership of the EU provide an interesting backdrop that have consequences for both the self-understanding among the Turkish communities in Europe and potentially have an effect on transnational activities as well as the organizational form.

The Political and Institutional Framework: Danish Integration and Immigration Policies

Until the end of the 1970s Denmark had an extremely homogeneous population. Traditionally Denmark never considered itself a country of immigration, due to, at least until recently, rather moderate immigration flows plus it being a small country and having a strong sense of national identity.

The Danish immigration policy reflects a tendency that can be traced in other European countries as well. The initial response to the labor migrants, in terms of integration, was to do nothing at all. Nobody, including the migrants themselves, expected them to reside permanently in Denmark and thus no steps were taken in regards to integration. The involved actors and institutions were primarily equivalent to the present Ministry for Employment, The National Directorate of Labor and local labor market agencies rather than specialized immigration agencies. However, the official end to migration also paved the way for a long-term immigration policy when parties on the left started talking about equal opportunities in the labor market for all nationalities and that people should be allowed to preserve their cultural background. As history has showed, the labor migrants did not return home nor have they repatriated to any large degree later on. On the contrary, they have used the right to be united with their families, which has created the need for a pro-active policy of immigration and strategy of incorporation.

The concept of integration was part of the political agenda in the early 1980s, first discussed by the Social Democratic government and later taken over by the Liberal/Conservative government with their political immigration policy from 1983 where it is stated that “the integration of immigrants in the Danish society is the main purpose of the politics of immigration”.11

Until January 1, 1999 the immigration law was decentralist, organized with The Danish Refugee Council as the main actor as it was responsible for housing and introduction to the Danish society after the refugees had received residence permits. People arriving via family reunifications were not part of this program. Integration became a core concept in these years, both in political considerations and publications and in the public discourse. The government’s white book Integration from 1997 presented a number of suggestions for coherent integration legislation.12 The preceding work and discussions included various NGOs and immigrant organizations active at the time. However, when Thorkild Simonsen from the Social Democrats was appointed internal affairs minister the report was put to rest and instead the Danish Act of Integration was introduced and implemented on January 1, 1999.

Although it included some of the suggestions from Integration, it generally has a tougher line in regards to integration. Looking more closely at the content of the law its foundation is a formal (legal) and substantial (social) citizenship perspective.13 The act aims at securing equal treatment and equal opportunities for all. However, as discussed, the law did not provide equal treatment as immigrants received lower public payments than native Danes. Second, immigrants (like Danes) had to be financially self-supporting.

Consequently, the Danish immigration policy since the mid-1980s has developed from being a labor market-regulative policy influenced by economics to focus primarily on aspects of socio-economic integration. The reason behind this focus can be found in the economic situation prevailing at the time. When the Danish economy went through times of decline and the labor market itself faced structural changes two problems occurred: first, the need for unskilled labor that the immigrant workers had been engaged in was diminished, and secondly a prevailing concern of rising unemployment rates set against the maintenance of an expensive welfare state. Some of the steps taken with the workfare policies were aimed at different groups, for example youth unemployment in the early 1990s and later repeated in the 1990s targeting immigrants. The key terms were self-sufficiency and autonomy. But the focus on socio-economic integration inevitably leads to a shift of burden towards the individual immigrant, where integration first and foremost becomes the responsibility of the individual. This neo-liberal tinge is convergent with the political and ideological development across Europe.14

Integration, Self-sufficiency and ‘Quid Pro Quo’

In 2001 Denmark changed governments and the Liberal and Conservative parties took over, strongly supported by the right-wing nationalist-orientated Danish People’s Party. The latest major developments in the Danish integration policy came with the implementation of the program En ny chance til alle (A New Chance for Everybody) from 2005 and with government strategy paper Noget for noget (Quid Pro Quo) in 2004. The first was targeted directly at immigrants and descendants while the latter was a program aimed at all residents in Denmark but in reality has the most severe consequences for ethnic minority groups. These programs were also the basis of the policy in 2009 but have been amended in different, often more restrictive, ways since. The primary focus has been to keep people in employment in order to be able to secure welfare services. The immigration- and integration policy is based on four sub-themes: To integrate the immigrants that already reside in the country before we accept newcomers; elf-sufficiency is both the means to and goal for integration; ‘Quid pro quo’: extra efforts should be rewarded and lack of effort punished; Consensus on the core values of society.

The focus on socio-economic integration inevitably leads to a shift of burden towards the individual immigrant, where integration first and foremost becomes the responsibility of the individual

The first policy theme centers on the relationship between integration and immigration. The main claim is that “we must integrate the ones that already reside in the country”. Like in other European countries, this points to a conflation of immigration and integration policies. Tougher integration policies become an instrument for restricting or discouraging immigration and indirectly serve as a mechanism for selecting the “best and the fittest” among the immigrants.15

Secondly, integration is defined as being “active participation on the labor market and contributing to the welfare state”. This economic framing becomes obvious when it is stated that “the government will work target-orientated towards foreigners becoming an active resource for the Danish society”.16 The keys to this goal lie in education and better proficiency in Danish. The problem and obstacle is located within the immigrants and they should take the first steps towards integration. The argument rests on the premise that the incentives for working have disappeared due to high social benefits, which therefore have to be changed in order to make it worthwhile to take a job. A reason for this could be lack of motivation and incentives but other reasons could also be barriers to the labor market, such as structural discrimination, ideas which are not mentioned in the paper.

The first two themes are related to the third theme, quid pro quo, which says that extra efforts should be rewarded and a lack of effort punished. In the government’s integration strategy this line of reasoning is put forth as the “will to integration – contract and consequence”, “we shall fight clientalization and show respect by posing demands” and “contracts of integration”. This line of thought is based on the government program Noget for noget from 2004 that holds the principle that extra effort should be rewarded and the opposite punished. The quid pro quo principle can be recognized in the integration policy. Non-citizens can get permanent residency much faster by showing good behavior and ”successful integration”, but the tendency is that it is exactly the extra effort that becomes the norm in order to obtain the same rights and recognitions as the majority.17

The last policy theme constitutes the grid of the overall discussion that integration should lead to a specific form of national identity. This policy theme in the age of globalization stresses homogenization as well as the Western forms of liberalism and the need to reassert the core values of society, the main opponent being Islamic values that rightly or wrongly are seen to clash with Western values. These values, which are political not ethical values, enforced newcomers through a repressive form of liberalism.18

In sum, we have a situation where issues of integration and immigration in the 1980s were discussed and defined mainly by labor market interests. In the 1990s the Social Democrats initiated a development of tougher demands of integration which was taken over and strengthened further by the Liberal-Conservative government and not least by the Danish People’s Party, which supported the coalition in the parliament. The Danish People’s Party is especially defined by a very restrictive approach to immigration and integration which it is has succeeded in keeping on the political agenda. Voters in Denmark still today are easily mobilized around these issues and they continue to hold high salience in electoral campaign and political discourse. The anti-immigration discourse and tough approach to integration have indeed become hegemonic in the sense that the Social Democratic and left-wing opposition actually articulates the same discourse. The only real opposition today is the social-liberal party (Radikale) and a small party on the far left (Enhedslisten).

Turning attention to the models of incorporation, various subsidy and other incentive structures are used to encourage organizational participation. In relation to this there has been a strong focus on individual inclusion as the Danish state has never encouraged immigrants to organize along ethnic or religious lines. Nor is there any juridical and political allowance for minority rights based on a minority status. This provides a strong explanation for the particular organizing processes taking place. While many immigrant organizations take the name of the home country, there are few collective national associations (as is the case in Sweden for instance). While there is a strong tradition of corporation across organizations, strong umbrella organizations are absent and the state has not encouraged immigrants to pursue them. In general, the government and relevant ministries have a weak tradition for including immigrant organizations in the decision-making processes. Since 1998 this has solely been done in the forum of the Rådet for etniske minoriteter (REM, the Council for Ethnic Minorities) and on the odd occasions when the prime minister has invited selected persons to a summit or at the yearly ”Integration Day” hosted by the Ministry of Integration.

The Danish state nonetheless has a wide-ranging system for supporting voluntarily organizations of which two types are central, namely the funding for setting up and running costs administrated by the local authorities (but with funds allocated from the Ministry of Welfare) to start up and run organizations. A minimum criteria of 50 members and an existence for over one year must be fulfilled to receive the funds. Most of the long-running ethno-national organizations mentioned in this article were supported while the recently established ‘diversity’ organizations and young professional networks were not.

The other important funding possibility is the funds controlled by the Ministry of Integration. These funds are exclusively reserved for projects dealing with integration, sub-divided into seven groups that all-in-all had €21.5 million for allocation in 2007. At the same time the government cut back funding for NGOs working on ethnic equality and antidiscrimination more broadly. The focus seems especially to be on projects that can guide the immigrants into the labor market.

Both types of funding require a high degree of professionalism and a specific organizational structure. The demands of professionalism have created a situation where immigrant and Danish organizations as well as labor market institutions, labor unions and political institutions compete for the same funds. Very few of the immigrant organizations have any funds for salary, which makes it a difficult and demanding task to go through the application process and afterwards the evaluation process.

Consequently, I argue that the Danish model comprises elements from corporatist, statist and liberal patterns of incorporation. For at least the last decade the liberal influences have been predominant, however. This would indicate a greater sphere for variety, but the reality is conformity and convergence in the organizing processes. Immigrant organizations in Denmark are generously funded compared to other countries, but the subsidies are coupled to the hegemonic discourse of integration. So although they have other choices, the immigrant organizations are positioned in a field that promotes a high degree of adaptation in the general organizing processes. The structures outlined in the previous sections are believed to have an impact on the collective organizing processes and the next part of the analysis looks further into how.

Turkish Collective Organizing Patterns in Danish Society

There is no accurate knowledge on the exact number of immigrant organizations in Denmark as such; organizations and associations receiving support from municipal or central level will be registered, but as the subsidies are allocated from various more or less transparent sources there is more than one register. Therefore, accurate information on the number and share of Turkish organizations does not exist either. A database on immigrant organizations done by Flemming Mikkelsen, a researcher on social movements, shows that Turkish organizations constitute a large share of the immigrant organizations, which indicates that Turkish immigrants for a start are not underrepresented when it comes to establishing organizations. Out of the 770 organizations listed in the database almost 150 are listed as Turkish (or Kurdish), but a large number of the total (almost 200) are trans-ethnic organizations or do not pay attention to ethno-national backgrounds as such, which means that Turks could also be members of these organizations. Most (Danish) research tends to agree that Turks have a high level of organizational activity compared to ethnic minorities in general though; the same tendency goes for political participation.19

Generally speaking, I found four main types of organizations to be dominant: ethno-national organizations (ENO), religious organizations (REO), trans-ethnic umbrella organizations (TUO) and recently, the young professional networks (YPN). Some organizations overlap these broad categories. This typology is constructed on the basis of the organizations’ own self-definition derived through interviews and/or aims descriptions in documentation. These self-definitions again were generalized and described in terms known from the literature on social movements. The category of religious organization intersects with other categories as some organizations would state that besides working with ethno-national issues religion also was an important aspect. Religion in general turned out to be a contested marker as some organizations would say of the other that ”they were too occupied with religion” or some persons would say that the ”the Alevis are too liberal”, etc. Religion has also been a driving force for establishing new organizations – either as a response to lack of religious representation as the case of Danish Muslim Immigrant Organization (DMIO) (see Table 1.), or as a response to society’s sweeping generalization as all newcomers being Muslims as the case of the Alevi organizations shows. An interview with FA from an Alevi organization illustrates the latter position when he states that:

All those who have come from Turkey are called Muslims … we would not put up with that. So we started our own association [Pirder, the local branch of the Alevi organizations] to show that we are different or rather profoundly different and we obviously also wanted to do integration work. We would like our people to be talented and resourceful for society […] How can you put it – to take matters into one’s own hand instead of waiting for the world or the authorities to take action.20

The oldest organizations generally have the most members and make no differences between Kurds, Turks and Alevis while the youth organizations have the highest level of activity. In the following table I have listed the most prominent Turkish (in the broadest sense) organizations in Denmark. Some of these organizations go several years back as for instance the Anatolsk Kulturforening was established in 1977 and Fey-Kurd in 1976 while the Foreningen ONE was established only in 2007.

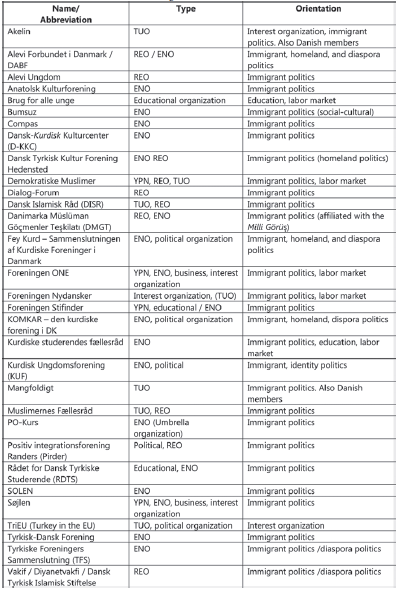

Table 1. List of Turkish organizations and associations in Denmark

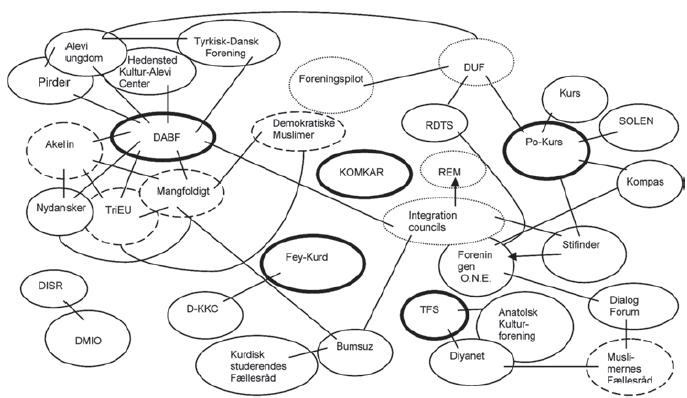

Turkish organizations in Denmark are, like the general organizational landscape, characterized by fragmentation. In Figure 1, I attempt to map the interlocking links between the different organizations. We see that for instance Kurdish organizations have fewer interlocking ties with other organizations than for instance the Alevis. The figure shows that Alevi organizations have been very active and have dense horizontal network ties to other Turkish organizations as well as vertical ties to authorities and mainstream organizations. Kurdish organizations oppositely have much less ties and the same can be said of religious organizations in opposition to the Turkish-Diyanet Foundation of Denmark (the Diyanet) such as DMIO.

Figure 1. Interlocks between selected Turkish organizations, trans-ethnic organizations and intermediating Danish institutions in 2005-2008

Note: Borders with large dot and dash lines indicate a trans-ethnic organization. *** dotted borders indicate Danish institution (e.g. Foreningspiloterne). Bold border indicates umbrella organizations.

Joining an organization is for many members first and foremost a social activity.21 People get together not to change society but to be together with other people. Several organizations have indeed protested against being labeled as politically orientated organizations, as one consequence of that has been the loss of economic support. Membership of this type of organization does not exclude members from joining other more political organizations. This type of organization will have a high level of voluntarism where most funds come from member fees and a closed structure in the sense that it mainly speaks to specific families or hemşehri a low level of outward communication and will rarely feel the need for detailed websites or newsletters.

The particular Danish system of incorporation points to a contradiction as it formally incorporates immigrants as individuals but de facto or indirectly encourages immigrant organizations to organize in ways that can secure representation of the different groups living here in the channels for consultative participation, which basically has meant organizing along ethnic lines.

Political climate and situation in Turkey (more generally in the homeland) also play an important part in the organizing processes and create political and religious cleavages among the Turkish immigrants in Denmark

The discursive structures have framed the immigrant political issues in a problem-based restrictive way that has had a clear impact on the organizing processes and on the immigrant political discourse. This has made certain types of claims seem possible and others less favorable. The institutional and discursive structures are conflated, which delimits the scope of strategies and action available for the immigrant organizations. My argument here is that the combination of existing substantial rights and a closure towards immigrant identity politics has created a situation where immigrant organizations display a large degree of adaptation that at the same time discourages claims to extend the field for negotiation. However, this does not mean that immigrants are left without autonomy and agency, but rather that their organizational profiles and activities are guided in specific directions where the organizations learn how to take advantage of the possibilities that are perceived to be open to them. The question of influence divides the members of the organizations. One member of the now defunct Council of Minority Youth Committees CMYC) for instance stated that “I don’t think that much can be achieved through the organizations. I mean, we don’t have any influence in reality”22 while another interviewee, MA, who has been active in a range of different organizations, in contrast told me in regards to access to the media that “we got an influence that perhaps was bigger than we were entitled to”.23

The overall organizing processes are influenced by at least three different factors. Firstly, the specific opportunity structures have on the one hand created a situation where the organizations articulate various discourses and pursue different types of claims but in reality follow the same trajectories and subsequently converge in their actions. This is especially visible in the neo-liberal turn adapted either consciously or unconsciously by very different organizations, for example the Foreningen ONE, the Foreningen Nydansker, and the Demokratiske Muslimer, making labor market issues an important part of their activities. The youth organization Stifinder for instance describes it own aims in the following way:

We – as entrepreneurs and leaders of the association STIFINDER – are a group of academics still under studies; the majority is born and bred in Denmark and the rest born in Turkey. As integrated students we want our share [persons taking higher educations] of the population to increase. We therefore have an aim of providing guidance to youths, with the purpose of enhancing educational work, and provide information about the possibilities that exist in the Danish educational system and on the labor market and thereby enlarge their horizon and enhance their motivation for further education.24

On the other hand, the organizations do not necessarily utilize the possibilities that actually do exist. The Danish electoral system offers good possibilities of listing and entering the local city councils, but rather few organizations pursued such goals on a collective level. Furthermore, I will argue that political entrepreneurship is important and points to agency but at the same time can be seen as a response to closed structures. Basically, it can be a tool to achieve social recognition in a society with few openings.

Secondly, the conflation of the political and discursive opportunity structures influences the organizing processes. The present openness for a secular reconfiguring of Muslim identity indisputably gains a lot of support from a broad political spectrum while orthodox Muslim identity is given few possibilities. Likewise are projects and discourses aiming at (in a progressive rhetoric) liberating or emancipating women, for example by entering the labor market or (in a prejudiced/negative framing) helping them transcend perceived repressive family patterns. The same goes for projects and organizations working against forced marriages, etc. However, what seemingly is a discourse of equality has an underlying twofold aim – to enhance self-sufficiency (and hence ease the ‘burden’ on the welfare state) and to prevent radicalism.

The structural position in the host society is not the only influencing factor; the political climate and situation in Turkey (more generally in the homeland) also play an important part in the organizing processes and create political and religious cleavages among the Turkish immigrants in Denmark. This is the third factor. The immigrants arriving from Turkey were both Turkish and Kurdish – the majority Sunni Muslims and a large minority Alevis. However, these internal differences mattered less as all were first and foremost workers and part of a working class proletariat. After the military coup in 1980 political and ethnic cleavages were widened and antagonisms between left-wing and right-wing and Turkish (ultra-)nationalists and Kurds blossomed and were also transplanted to Denmark. These disputes have diminished today where I found that, for instance, Kurdish factions are working together; however, new cleavage lines also have appeared. Despite having many vertical ties, Alevi organizations for instance have increased their distance from Sunni Muslim organizations. Alevis subsequently applied to be become a “recognized belief system” independent from other religious, most notably Muslim, groups. Their application was successful and Alevi organizations were officially given the status of a recognized belief system by the Church Ministry in 2007. The Alevi organization wrote in the press release announcing the new status that “As Alevi belief system and community have to this date not experienced problems in relation to living out our religion or opposition or conflicts in regards to being integrated into the Danish society”.25 But in interviews with members of the different Alevi organizations, the informants emphasized that they, especially after the cartoon crisis in 2005, did not want to be taken as Muslims.

Comparing Turkish organizations with Muslim organizations indicate that Turks on a general and at least a discursive level are very interested in promoting processes of integration and to some degree assimilation

The cartoon crisis deserves to be discussed on a more general level however. When the culture editor of Jyllands-Posten commissioned the cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad and chose to print them on September 30, 2005, nobody could imagine what would happen afterwards.26 Turkish organizations in general (with some exceptions such as the Milli Görüş and/or Fethullah Gülen-related organizations) have a relaxed relationship to religion in a Danish context where most religious questions are left to the Diyanet also present in the country. Comparing Turkish organizations with Muslim organizations indicate that Turks on a general and at least a discursive level are very interested in promoting processes of integration and to some degree assimilation27 but I will also claim that generational aspects may be what matters as Pakistani and Somali youth organizations express attitudes very similar to the Turkish youth.28

However, the crisis somewhat disturbed or changed that relationship. The crisis conditioned a change of perception towards Muslims in general, which first meant that such were regarded with skeptics and later had the unexpected outcome that people started differentiating between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ Muslim which of course can regarded as a productive outcome.29 The problem is, however, that the distinction is ‘slippery’ and also that Turkish Muslims afterwards were questioned and had to position themselves within this dichotomy.

This new religious positioning is perhaps easier to investigate on an individual level as several of my informants for the first time had to make utterances and even public statements about their own religiosity. One of my informants states that:

I must admit that this is the first time that I have been out and have been this active in relation to religion and integration in general because the other activities we had were also promoting integration but they rested more on a mixed perspective. This is the first time I am member of an organization that only consists of ethnic or how shall I put it new Danes with the common denominator that they have a Muslim background of this or that type.30

This organization was the Democratic Muslims which entered the organizational landscape exactly because of the new possibility structures as well as a potential chance to reposition one self – either out of necessity or of own free will. My informant YA later tells me that when she decided to go into politics, she was asked by a journalist what her “father felt about her living on her own and entering politics”. Despite being active in the organization loosely described above, she defines her relationship to religion as “I mainly consider myself a democrat and Islam probably plays as small a role in my daily life as it [religion] does in yours”. Other Muslim organizations later criticized the Democratic Muslims as they created an unfair gap between Muslim groups by buying into the public pressure for making public confessions on being democratic minded if one is a Muslim.

On a general level the crisis had an immediate impact on Turkish organizations as they almost all had to take public positions on the crisis – and for some, for example Alevi organizations, this presented a possibility to make a demarcation to religious orthodoxy — but after a while the crisis stopped being discussed to the same degree and today it is very much discussed in relation to so-called radicalization and terrorism which most often does not include the Turks. On an individual level, however, the crisis had an impact as some of my informants have felt the political climate worsen and for some this has meant reflecting about staying in Denmark or moving elsewhere. Speaking about the personal impact of the crisis one interviewee, MK, told me that:

Believe me, it cannot be explained by words… how much it has changed me and I consider how much hasn’t it changed for others, it is … how can I explain it? OK, if we say that this glass is Danish culture and this glass Turkish culture, then I was everywhere, I was in the middle and I had perhaps created a new culture for myself from these two and it went really really well … but after all that happened is it as if everything is separated again, separated the culture I had created and now I am stuck in the middle and considering which way to jump … I guess this is the best way to describe it and I think it is extremely sad.31

Leaving aside the cartoon crisis and returning once again to the overall mode of incorporation the conclusion is that the seemingly liberal Danish approach is not altogether liberal. A purely liberal approach would aim to create equal opportunities for all in order to enhance the individual’s chances of self-support, but the relatively weak antidiscrimination efforts, direct and institutional/structural, do not live up to this goal. Neither would I expect to find intermediating institutions like integration councils. Liberal approaches would also be expected to be much more decentralized, as for instance in the UK, than is the case in Denmark. Instead, the Danish approach contains elements of corporatist, statist and liberal approaches by having liberal goals of self-sufficiency and self-responsibility but at the same time making use of social and top-down control. This is perhaps best illustrated with initiatives as the integration tests, integration contracts and increased requirements for naturalization.

The Danish approach contains elements of corporatist, statist and liberal approaches by having liberal goals of self-sufficiency and self-responsibility but at the same time making use of social and top-down control

The Danish system in this sense is hard to define. On the one hand there is a general openness for immigrants organizing collectively as anybody is free to establish associations, etc. This provides a good setting for bottom-up activities in civil society, but on the other hand, subsidies are being allocated in accordance with a narrow definition of integration and thus controlled from the center.

As Togeby has argued, I will also claim that Danish society is closed in regards to opportunities for immigrants.32 Although the legislation aims at providing equal opportunities, the reality remains that it is much harder for immigrants to gain social status through the normal channels. Still today while Denmark is de facto multicultural society, immigrants are underrepresented in the higher strata of society, although some groups have shown strong social upward mobility. To overcome this dislocation two options for social recognition then seem to be available, that is either through political entrepreneurship or by entering the ‘integration industry’ (for example, integration workers, counselors, etc.). After responsibility for facilitating the integration process was moved to the municipalities a large number of jobs in the integration area have been established at different levels, interpreters, neighborhood programs, language schools, social workers, at municipal level, ad hoc projects and so on. A large share, if not most, of such positions are occupied by people with an immigrant background. The problem seemingly is that many people have ended up in this occupation as it has been their only possibility for a career. This opportunity rests on the dubious premise that immigrants necessarily know what is best for other immigrants. Also, a large share of my informants presently belongs to this category or had done so previously. One informant, YA, had just submitted a master’s thesis for a university degree and still had (self-perceived) bleak expectations about ending in such a position as the only offers YA had received so far was of this kind. For others, however, it can as mentioned be a site for gaining access to the political channels.

Several of my informants are or have been active in mainstream political parties. Nine had been listed for municipal elections and three had been elected. Three were candidates in the 2007 national election and two were elected to the parliament. Several had previously been active members of integration councils in different municipalities. The high number definitely indicates that participating in established political channels can be an outcome of being active in civic organizations. In the interviews it also became clear that neither opportunism nor pure altruism were the driving forces. Instead the given persons had experienced the limitation of immigrant organizations’ influence on the political decision-making and took their experiences and network a step further up the social ladder.

Conclusions

The impact of the integration and citizenship regime stands as a major internal influence on the organizing processes. Another influential factor is that even non-citizens in most ways enjoy substantial rights in most regards, which arguably have suppressed and diminished much of the claims making we find in other national settings which provide less extensive rights. This is also an explanation for a general organizational decline in both new organizations and activities. What could be expected is that the claims making would be directed towards issues and areas where non-citizens and immigrants do not have access to the same entitlements as citizens, but this is not happening to any extent either. Again, I will point to the political opportunity structures having an identifiable impact but very much on the discursive level. The issues deemed important for many of the immigrant organizations are the same issues highlighted by the government and Ministry of Integration, for example employment, gender equality, female participation, etc. Saying so does not mean that these issues are not important for the Turkish immigrant organizations, but it is striking to see how they have gained hegemony in the organizational discourse also.

Organizations would stress the empowerment aspect or emancipatory perspectives, but the end goal is the same: getting immigrants on the labor market. The interesting finding is that the incorporation of this discourse is happening across the organizations and religious, cultural, student and ethnic organizations strive towards the same goal. This discursive convergence can perhaps also explain why there is less ideological strife between the different fractions within the Turkish minority groups in a Danish context.

Consequently, there is outspoken convergence in the understanding of integration in Danish society among the different organizations, but the divergence occurs and becomes visible especially when looking at transnational engagements and identification. The other important cleavage structure is centered on religious categories and what can be identified as a discursive shift from being guest workers to being ethnic minorities to being, externally, Muslims vis-à-vis Danish society and, internally, democratic Muslims vis-à-vis extremists/orthodox/fundamentalist/radicals.

Moreover, I conclude that the internal differences on one level have decreased in terms of open struggles, although the internal variation remains rather widespread reflecting the ethnic, generational, and religious diversity. On another level, the differences have become more pronounced and especially the Alevi organizations’ formal application of not being considered as a Muslim minority group has sparked this tendency where it reflects a distinction transplanted from Turkey.

Endnotes

- Lise Togeby, “The Political Representation of Ethnic Minorities: Denmark as a Deviant Case”, Party Politics, Vol. 14, No.3 (2008), pp. 343-361.

- Yasemin Nuboğlu Soysal, Limits of Citizenship: Migrants and postnational Memebership in Europe (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994).

- Soysal, Limits of Citizenship…, p. 85.

- Soysal Limits of Citizenship…, p. 86.

- Martin Bak Jørgensen, “National and Transnational Identities: Turkish Organizing Processes and Identity Construction in Denmark, Sweden and Germany”, unpublished PhD thesis, AMID, Aalborg University, 2009.

- Danish Statistics, “Population in numbers” (Copenhagen, 2009).

- Dansk Flytgningehjælp, Tyrkiet – landerapport (København, 2005).

- Nyt fra Danmarks Statistik, “Kvindelige efterkommere indhenter kønsforskelle”. Nr. 528 December 17, 2007.

- Danmarks Statistik, “Danske statsborgerskaber er ulige fordelt blandt udlændinge” (www.statistikbanken.dk/bef3, 2006).

- Ministeriet for Flygtninge, Indvandrere og Integration, Årbog om Udlændinge i Danmark 2005 (København, 2005), p. 133.

- Redegørelse af 12.4.1983. Integration (København, 1983).

- Betænkning nr. 1337/1997. Integration (København, 1997).

- Lov nr. 474 af 1. juli 1998. Integrationsloven.

- Carl-Ulrich Schierup, Peo Hansen & Stephen Castles, Migration, Citizenship, and the European Welfare State – A European Dilemma (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006).

- For example María Bruquetas-Callejo et al, “Policymaking related to immigration and integration. The Dutch Case”. IMISCOE Working Paper: Country Report WP-15, 2005.

- Regeringen, En ny chance til alle – regeringens integrationsplan (København, 2005), p. 5.

- Regeringsaftale, Noget for noget (København, februar 2004).

- Christian Joppke, “Beyond National Models: Civic Integration Policies for Immigrants in Western Europe”, Western European Politics, Vol. 30, No.1 (2007), pp. 1-22.

- Togeby, “The Political Representation…”

- Interview with FA, August 2006 – Alevi Forbundet i Danmark.

- Jose C. Moya, “Immigrants and Associations: A Global and Historical Perspective”, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, Vol. 31, No.5 (2005), pp. 833–64.

- Interview with BG, August 2008 - CEMYC.

- Interview with MA, September 2006.

- The quotation is taken from Stifinder (www), ”Formål”, 2008. The website is now defunct.

- DABF, ”Pressemeddelelse Alevierne er nu godkendt som trossamfund i Danmark”, DABF, 5.11.07.

- See Lasse Lindekilde, Per Mouritsen & Richard Zapata-Barrero, ”The Muhammed cartoons controversy in comparative perspective”, Ethnicities, Vol. 9, No.3 (2009), pp. 291-313.

- See for instance Lene Kühle, Moskeer i Danmark (Århus: Univers, 2006).

- Andreas Relster, “‘Så kan det være de vågner og vi får svar’”, Information, January 8th 2010.

- Jørgensen, “National and Transnational Identities…”

- Interview with YA, September 2006 – Social Democratic Party amongst other affiliations.

- Interview with MK, September 2006 - Søjlen.

- Togeby, “The Political Representation…”