Introduction1

After the end of the Cold War and with the adoption of “Vision 2023: Turkey’s Foreign Policy Objectives,” Turkish foreign policy and diplomacy towards the Balkans changed. Consequently, Turkey began to play a proactive and mediating role in the Balkans, skillfully utilizing shared geography, history, economics, and culture. In 2009, initial steps were undertaken towards the adoption of trilateral relations between Turkey, Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina. This tripartite diplomatic model was a step forward in enacting of new trilateral relations and a multi-dimensional model to tackle a number of regional problems. Turkey encountered a multi-polar world, whose changing security, political, and economic realities could be addressed more successfully by means of a trilateral relations model.2

Turkey had already adopted a trilateral relations model elsewhere; for example, Turkey-Russia-Iran, Turkey-Afghanistan-Pakistan, Turkey-Poland-Romania, Turkey-Azerbaijan-Georgia, and Turkey-Azerbaijan-Iran.3 Nonetheless, the limited number of research studies on trilateral relations inhibits a proper understanding of Turkey-Serbia-Bosnia and Herzegovina political, economic, trade, and cultural relations. Thus, a proper analysis of the main declarations, agreements, and official statements is inevitable for determining to what extent trilateral relations as a diplomatic model has been successful. In particular, such an analysis would reveal how trilateral relations at the presidential, ministry of foreign affairs, and ministry of economy and trade levels contributed to political, diplomatic, economic, and trade trilateral relations between Turkey, Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Trilateral Relations at the Presidential Level

Turkish foreign policy has significantly changed in the past few decades. The 1990s changes to the world order and Turkish internal political dynamism contributed towards a much more proactive and dynamic foreign policy. These developments went hand-in-hand with Turkey’s ever-increasing population, its geopolitical and geostrategic position, resources, economic growth and development, its political continuity and stability, and its military power. “Turkish Strategic Vision 2023” projected the country as a great power with a global character and effective external relations.4 In this regard, since the 1990s, Turkish involvement in the Balkans has been on the rise. The turning point of greater Turkish involvement in the Balkans, especially in Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, began after the signing of the İstanbul Declaration in 2010.5 The President of Turkey, Abdullah Gül, the President of Serbia, Boris Tadić, and the President of Bosnian Presidency, Haris Silajdžić, accompanied by their foreign ministers, met on April 24, 2010, in İstanbul at the first trilateral relations meeting at the presidency level. This historic meeting, which resulted in the adoption of the İstanbul Declaration, opened the door for much more dynamic tripartite relations between Turkey, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia.6

The first trilateral meeting at the presidential level led to the opening of a new page in relations between these countries. At first, the leaders of Turkey, Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina had to counter long-standing historical animosity and mistrust. Therefore, the initial beginnings of relations emphasized questions of peace, reconciliation, prosperity, stability, and territorial integrity. The major outcome of the first meeting was a regional reconciliation process and Serbian recognition of the territorial integrity and sovereignty of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Serbian President Tadić clearly stated, “Serbia would not undertake any steps that would destabilize Bosnia and Herzegovina, nor would it challenge its borders and its integrity, which would endanger the stability in the region.”7 Since 2010, Serbian leaders, often under political pressure from Bosniak state-officials, have made official statements, repeatedly, that they recognize the territorial integrity and sovereignty of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Thus, the meeting was “a turning point” and “a new beginning” in Serbia-Bosnia and Herzegovina diplomatic relations.

Thus the first trilateral meeting, as one of the most important diplomatic events in the Balkans, positioned Turkey as a key mediating power that had the primary goal of bridging Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina and strengthening cooperation among the constituent peoples

Consequently, President Silajdžić, with the other members of the Bosnia and Herzegovina presidency, visited Belgrade, and Serbian President Boris Tadić participated in the 15th anniversary of the Srebrenica genocide. Then, the Serbian National Assembly also passed the decision and apologized for the ‘crimes’ (not genocide) committed in Srebrenica.8 Thus the first trilateral meeting, as one of the most important diplomatic events in the Balkans, positioned Turkey as a key mediating power that had the primary goal of bridging Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina and strengthening cooperation among the constituent peoples, i.e. the Bosniaks, Serbs, and Croats in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Finally, this meeting also strengthened the position of Turkey as a key power that used proactive diplomacy to promote the Western Balkans’ integration into the EU and NATO, with the support and appreciation of the EU countries and Brussels.9 Actually, the first trilateral meeting was a diplomatic boost for the upcoming EU-Western Balkans Summit in Sarajevo on June 2, 2010.

The second trilateral meeting at the presidential level was organized on April 26, 2011, in Karađorđevo in Serbia; it was attended by then President of Turkey Abdullah Gül, President of Serbia Boris Tadić and Presidents of the Bosnian tripartite Presidency Nebojša Radmanović, Željko Komšić, and Bakir Izetbegović. The meeting was held at the time when local Bosnian Serb politician Milorad Dodik was threatening with the referendum on the judicial system. However, the trilateral meeting again articulated the territorial integrity and sovereignty of Bosnia and Herzegovina.10 In this regard, Serbian President Boris Tadić restated his remarks from the first trilateral meeting Bosnian territorial integrity and sovereignty: “Serbia will never back a referendum in Bosnia that would lead to the division of Bosnia and question its territorial integrity and entirety.”11 Similarly, Turkish President Abdullah Gül repeated, “Turkey is employing utmost efforts to strengthen that cooperation and see all Balkan countries under one EU and NATO umbrella.” Overall, the second trilateral meeting focused on peace, reconciliation, detachment from the 1990s bloody conflict culture and mentality, the centrality of the Western Balkans, the region’s common future in the EU, and NATO integration.12

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan speaks at the Turkey-Serbia Business Forum in Belgrade on October 10, 2017. MURAT KULA / AA Photo

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan speaks at the Turkey-Serbia Business Forum in Belgrade on October 10, 2017. MURAT KULA / AA Photo

On May 14-15, 2013 in Ankara, President Gül hosted Serbian President Tomislav Nikolić and Presidents of the Bosnian tripartite Presidency Nebojša Radmanović, Željko Komšić and Bakir Izetbegović. Besides (re)affirming Bosnian territorial integrity and sovereignty, this meeting also articulated Bosnia-Serbian relations in particular and regional cooperation in general. The presidents also adopted the Ankara Summit Declaration in which they underlined the Western Balkans’ prosperity and the common future of the region based on European values, democracy, rule of law, and cultural pluralism.13 They also declared that trilateral relations as a mechanism should be used as an institutional framework for regional cooperation. This meeting also significantly articulated fostering further economic, cultural, educational, scientific, energy, infrastructure, transportation, sports, and tourism cooperation. With the adoption of the “Declaration on Economic and Commercial Cooperation” at the ministries of economics and trade, economics and trade relations between Turkey-Serbia-Bosnia and Herzegovina were articulated alongside the earlier focus on reconciliation, peace, dialogue, and territorial integrity and the sovereignty of the Balkans states. Actually, the main motto of the summit was “Building the Future Together.”14

Although the Ankara Summit Declaration set the next trilateral meeting for 2014 in Sarajevo, it was postponed to 2018, as different political issues contributed to the decline of trilateral meetings at the presidential level in the following years. In particular, Serbian President Tomislav Nikolić made a strong stand against then Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s remark: “Kosovo is Turkey and Turkey is Kosovo.” However, trilateral meetings at the level of the ministries of economics and trade and the ministries of foreign affairs took place regularly from 2014-2018.

On January 29, 2018, in İstanbul, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan hosted Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić and Bosnian Presidency Member Bakir Izetbegović. Renewed trilateral meetings at the presidential level took place after five years, with an agenda similar to those of the above-mentioned three meetings. The three presidents again reiterated the territorial integrity and sovereignty of Bosnia and Herzegovina. However, Serbian President Vučić strongly articulated the position of the Republika Srpska under the Dayton Peace Agreement, stating, “all we ask from the Bosniaks is to make Serbs in Bosnia feel safe and –just as we do not question Bosnia’s territorial integrity– we ask them to treat Republika Srpska the same.”15

Building upon these positive developments, from 2010 to 2013 tripartite relations between Turkey, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia contributed to regional cooperation, and the EU and NATO integration processes

In the Western Balkans, Serbia was given a chance to play a much more active role in the process of reconciliation, peace, and stability, especially among the Bosniaks and Serbs. Besides the focus on the relationship between Serbs and Bosniaks, the three presidents also agreed on infrastructural and transportation projects, such as linking Sarajevo and Belgrade through an inter-connecting highway, which will be financially supported by Turkey. This meeting was organized at the time of the peak of bilateral relations between Turkey and Serbia; their trade volume exchange in 2017 surpassed €1 billion. Between 2017-2018, there were a number of bilateral meetings between the presidents of Turkey, Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina. On a number of occasions, Serbian President Aleksander Vučić and President of the Bosnian Presidency Bakir Izetbegović visited Turkey. On October 10, 2017, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan visited Belgrade and on May 20, 2018, he paid a visit to Bosnia and Herzegovina.16 These meetings indicate that these countries effectively used both trilateral and bilateral relations.

Trilateral Relations at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Level

Turkey-Serbia relations began to improve in 2009 when Turkish President Abdullah Gül visited Serbia after a lapse of 23 years. In the same year, a Defense Cooperation Agreement and a Free Trade Agreement were signed. Turkey used the platform of the South East European Cooperation Process (SEECP) for the actualization of a mediating role in the Western Balkans. However, the major breakthrough was made after Turkey, Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina decided to institutionalize their relations, and as a result, signed the Trilateral Consultation Mechanisms on October 10, 2009, at the level of the Ministers of Foreign Affairs.17 Trilateral relations at the presidential level and at the level of the ministry of foreign affairs contributed to mutual diplomatic recognition between Turkey, Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, which led to the opening of embassies in Sarajevo, Belgrade, and Ankara. Another positive development was the signing of a visa-free agreement between Turkey, Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, which contributed significantly to the development of the tourism industry and trade between these countries. Because of the adoption of the Trilateral Consultation Mechanisms in 2009, three meetings at the ministry of foreign affairs level were organized in October, November, and December, respectively.

From 2010 to 2013, nine meetings were organized at the level of ministers of foreign affairs. During this period, Turkish Minister of Foreign Affairs Ahmet Davutoğlu actively engaged his counterparts from Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Ministers of Foreign Affairs from Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina included Vuk Jeremić, Sven Alkalaj, and Zlatko Lagumdžija. It is important to mention that in 2013, two more Trilateral Consultation Meetings of the Ministers of Foreign Affairs of Turkey, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia were organized on May 8, 2013, and September 24, 2013.18 During this critical period from 2009-2013, the ministries of foreign affairs were addressing questions of regional cooperation, good neighborly relations, economic cooperation, and EU and Euro-Atlantic integration. Such meetings were also important for setting the agenda of the Trilateral Meetings at the presidential level on May 14-15, 2013, in Ankara.

Although on June 10, 2014 and on December 28-29, 2015, Ahmet Davutoğlu visited Belgrade at the invitation of Serbian Minister of Foreign Affairs Ivica Dačić, relations between Serbia and Turkey continued under the shadow of President Nikolić’s strong stand against Erdoğan’s remarks on Kosovo and his apparent withdrawal from trilateral meetings. However, trilateral relations were re-established from 2015 to 2018. Two meetings were held at the ministry of foreign affairs level on September 29, 2015, and on September 23, 2016, in New York. Ministers of Foreign Affairs Ivica Dačić, Feridun Hadi Sinirlioğlu, Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu, and Igor Crnadak also used the opportunity to revive trilateral meetings on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly.19 They reaffirmed the significance of the Trilateral Consultation Mechanisms, and agreed that cooperation should be extended to parliaments, diplomatic academies, and universities. Foreign ministers and political directors should develop specific areas of cooperation, especially for the envisioned Trilateral Business Forum.

In 2017, there were two trilateral meetings of the Foreign Ministers of Turkey, Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina. They meet on September 21, 2017, in New York and on December 6, 2017, in Belgrade.20 The ministers of the three countries reinforced their common foreign policy objectives and a strong commitment to EU full membership, and underlined their economic cooperation and increasing trade exchanges in comparison to previous years. For instance, Minister Dačić noted that in 2017 trade in goods between Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina increased 15 percent, while between Serbia and Turkey increased 12 percent.

Due to the signing of trade agreements, Turkish-Serbian-Bosnian Herzegovinian diplomatic, trade, and cultural relations have been rapidly developing

Another outcome of these two meetings was the establishment of a joint trade representative office of Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina in İstanbul. Finally, these meetings also gave birth to the initial idea of building a Belgrade-Sarajevo highway. The trilateral meetings at the ministry of foreign affairs level offered an opportunity for opposition political parties among Serbs in Bosnia and Herzegovina, especially predominantly Serb political parties under the Alliance for Change, to position themselves as constructive in building Serbian-Turkey relations. These parties, under the leadership of Serb President of the Presidency Malden Ivanić and Minister of Foreign Affairs of Bosnia and Herzegovina Igor Crnadak, could get closer to the Serbian leadership, and gain support for their plight against the majority Dodik’s party SNSD coalition in Republika Srpska.

Trilateral Relations at the Ministry of Economy and Trade Level

Although the ministries of economy and trade from Turkey, Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina were involved in trilateral relations from 2009, their much more systematic involvement began in 2013. Ministers of Economy and Trade Nihat Zeybekçi, Zafer Çağlayan, Rasim Ljajić, and Mirko Šarović have been very active in fostering economic and trade relations between Turkey, Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Thanks to their active foreign policy, on May 15, 2013, the Trilateral Balkan Summit and Turkey-Bosnia and Herzegovina-Serbia Business Forum was organized in Ankara. This institutional activity led to the adoption of the “Declaration on Economic and Trade Cooperation between Bosnia and Herzegovina, Republic of Turkey and Serbia.” The ministers also agreed to establish the Joint Commission on Economic Cooperation between Turkey, Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina (Trilateral Trade Committee) to present a joint appearance on third markets.21 The aim of the Committee is to provide a forum for the “exchange of information and experiences on issues of multilateral trade agreements, regional cooperation and trade policies, promotion of foreign investment and opportunities for cooperation between the three countries in different sectors regarding economic priorities, research opportunities and encouragement of economic cooperation in third markets.”22

The ministries of economy and trade intensified their relations from 2015 to 2017. The Trilateral Trade Committee between Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Turkey was held in Ankara on August 17-18, 2015, and in Belgrade on October 19, 2015. These two meetings contributed to the adoption of a Mid-term Program on Cooperation and an Action Plan. Then, on October 20, 2015, a Trilateral Forum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Turkish, and Serbian Entrepreneurs was organized in Sarajevo. This trilateral forum focused on Turkish foreign direct investments, which then stood at $80 billion. The ministers of economy and trade argued that in the following years, Turkish foreign direct investments in the Western Balkans, including Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, should increase. The ministers, along with 82 businesspersons from Turkey, Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, emphasized significant opportunities in the energy, transportation and communication sectors with a focus on the proposed Belgrade-Sarajevo highway. One of the major outcomes of this meeting was the opening of a joint trade and tourism branch office of Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina in İstanbul. In addition, Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina may use Turkish trade branch offices in 160 countries around the world.23

Trilateral relations also played a significant role in Turkish foreign direct investments in Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, countries that have gradually become desirable investment destinations for Turkish companies

On October 26-27, 2016, the Trilateral Turkey-Serbia-Bosnia and Herzegovina Trade Committee and Trilateral Business Forum were held in İstanbul. The Trilateral Business Forum was hosted by the Foreign Economic Relations Board (DEİK). The Forum brought together more than a hundred companies in the field of agriculture, food, livestock, energy, transport, logistics, and the automobile industries. Some of the companies included Delta Agrar, Victoria Group, Victoria Oil, Krušik, Agropapuk, Bosphorus Hotels Serbia, Transporti Man Market, Bimal dd Brčko, GUMA-CO doo Bugojno, Promo d.o.o Donji Vakuf, Poljorad doo Travnik, GAMEHA doo Sarajevo, Menprom doo Tuzla, Dukat doo Tešanj, Heyoti doo Sarajevo, SOHO Wintech PVC doo Sarajevo, Sarajevo International doo Sarajevo, Radić doo Gradiška, Elker Prijedor, and Natron Hayat. Minister Zeybekçi made a clear statement: “the more joint investments, production and trade we achieve, the more significant the meetings of the presidents of our countries will be.”24 This statement implies that trilateral relations flowed downwards from the presidential and ministry of foreign affairs to the ministries of economy and trade, thus being much more actualized in terms of Foreign Trade Agreement realization and enlargement. The ministers argued that trilateral relations should consider foreign direct investments in energy, communication and transportation, tourism, agriculture, and livestock farming.25 Finally, the ministers of economy and trade used this opportunity to celebrate the official opening of the Serbian-Bosnian Open Trade Office in Turkey.

From 2017 to present, the Trilateral Trade Committee between Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Turkey took a backseat to bilateral relations and occasional bilateral visits of ministers of economy and trade. For instance, on October 10, 2017, the Serbia-Turkey Business Forum was organized in Belgrade with the participation of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić, and Ministers of Trade from Turkey and Serbia Nihat Zeybekçi and Rasim Ljajic. This Forum also brought together more than 200 companies from Serbia and Turkey.26 Similarly, since 2017, the ministers of economy and trade of Turkey and Bosnia and Herzegovina have held several high-ranking bilateral meetings in Sarajevo and Ankara.

Trilateral Relations: Political, Economic, and Trade Prospects and Challenges

Tripartite relations between Turkey, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia started because of a political and diplomatic initiative, especially after the adoption of the İstanbul Declaration. Almost all trilateral meetings at both the presidential and ministry of foreign affairs levels have articulated peace, reconciliation, prosperity, stability, territorial integrity, and regional cooperation. The first phase of trilateral relations was especially successful because of several factors: the adoption of the Trilateral Consultation Mechanism, the establishment of diplomatic relations between Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, the opening of embassies in Sarajevo, Belgrade, and Ankara, the first state-level exchange of visits between Sarajevo, Belgrade, and Ankara, the adoption of the Srebrenica Resolution by the Serbian Parliament, and the participation of Serbian President Boris Tadić and Aleksander Vučić in the commemoration of the Srebrenica genocide. This period was indeed a breakthrough in diplomatic relations between Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Turkey. Building upon these positive developments, from 2010 to 2013 tripartite relations between Turkey, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia contributed to regional cooperation, and the EU and NATO integration processes.

In terms of political and diplomatic accomplishments, trilateral relations have also faced several drawbacks. First, although peace, reconciliation, and territorial integrity were at the center of trilateral relations, Serbia made no clear stand on the Srebrenica genocide, crimes against humanity, or its overall involvement in the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Peace and reconciliation were well-intentioned diplomatic initiatives, yet they lacked a proper strategic plan for tackling questions of peace, reconciliation, and justice. In fact, the Trilateral Relations Mechanism could have been used as a platform to strengthen the already active role of international and local courts in tackling crimes against humanity. Second, the trilateral relations emphasized respect for the territorial integrity of Bosnia and Herzegovina, without considering a clear position vis-à-vis the entity of Republika Srpska within Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Turkey and Bosnia and Herzegovina have historical and diplomatic relations rooted in deep historical and cultural ties. Such ties are institutionally maintained through the International University of Sarajevo, Yunus Emre Institute, and TİKA

In fact, during the last trilateral meeting at the presidential level in 2018, Alexander Vučić equated the territorial integrity of Bosnia and Herzegovina with the territorial integrity of entity Republika Srpska. Thus, the trilateral relations failed in tackling the border dispute between Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, primarily by omission; this question was not on the agenda of any of the meetings from 2010 to the present. Third, the three countries greatly differ on the Kosovo question, which in 2013 caused a significant disruption of tripartite relations between Serbia, Turkey, and Kosovo. Trilateral relations could have been used to integrate Turkey and Bosnia and Herzegovina as mediating countries in the Kosovo-Serbia dispute. Moreover, the trilateral relations failed to determine a clear position on the presence of Russia in the Western Balkans, as the three countries developed different preferential relations with Russia because of the U.S. and EU pressures. Serbia and Turkey have a much more pro-Russian foreign policy while that of Bosnia and Herzegovina is rather neutral.

Although trilateral relations strongly supported EU and NATO integration, in the past several years, Serbia has changed course and adopted a resolution of neutrality. Actually, thanks to Turkish support as a NATO member, on April 22, 2010, in Tallinn, NATO granted the Membership Action Plan (MAP) to Bosnia and Herzegovina.27 However, Serbia’s newly developed position greatly affected NATO-membership oriented countries in the Western Balkans, including Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, and Montenegro, and the NATO aspirations of Bosnia and Herzegovina began to be seriously questioned by Serb politicians in Bosnia and Herzegovina, who have been following Serbian policies. Finally, although Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina gave full support to Turkey after the July 15, 2016 coup d’état attempt by the FETÖ terrorist organization, specific political, diplomatic and legal activities were not made a part of the trilateral relations agenda.

Trilateral relations gave significant impetus to the signing of bilateral trade agreements between Turkey and Serbia. As early as in 2003, Turkey ratified a Free Trade Agreement with Bosnia and Herzegovina. In 2009, Serbia and Turkey signed the Free Trade Agreement, which significantly contributed toward trade exchange. On January 30, 2018, Turkey and Serbia ratified new a Free Trade Agreement on the customs-free exports of meat, oil, and bakery related products from Serbia to Turkey.28 Thus, due to the signing of trade agreements, Turkish-Serbian-Bosnian Herzegovinian diplomatic, trade, and cultural relations have been rapidly developing. These relations were coupled with Turkish GDP growth that reached its climax in 2010 (9.2 percent) and 2011 (8.8 percent).

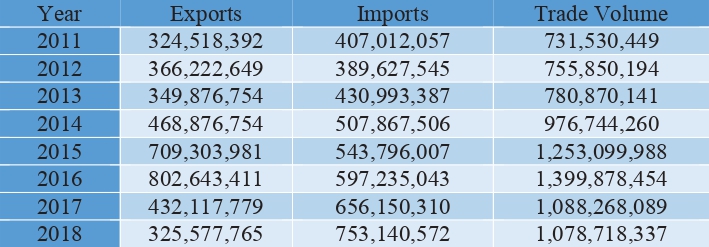

Trade exchange between Turkey, Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina significantly increased because of trilateral relations.29 In 2011, Bosnia and Herzegovina exported 324,518,392 BAM in products to Turkey and imported 407,012,057 BAM in products from Turkey. However, in 2018, Bosnia and Herzegovina exported 325,577,765 BAM and imported 753,140,572 BAM in products from Turkey. In 2011, the trade volume between Turkey and Bosnia and Herzegovina stood at 731,530,449 BAM while in 2018 it stood at 1,078,718,337 BAM.30 Thus, the Daily Sabah newspaper rightly pointed out:

the bilateral trade volume between Turkey and Bosnia-Herzegovina was calculated at $71.6 million in 2003 when FTA took effect. Since then, the bilateral trade volume has increased by nine-fold and reached $617.6 million. Last year (2017), Turkey’s exports to Bosnia-Herzegovina were $348.7 million while the value of imports from the county stood at $269 million.31

Table 1: Bosnia and Herzegovina and Turkey: Exports, Imports, and Trade Volume in BAM

Source: Foreign Trade Chamber of Bosnia and Herzegovina32

Trade exchange between Turkey and Serbia has increased tremendously in the past eight years.33 Certainly, the improved economic and trade relations were a direct result of trilateral relations and the diplomatic initiatives of both the Turkish and Serbian governments. Since 2013, Turkey began to perceive Serbia as one of the most important Western Balkans countries in terms of economics, trade, and security.

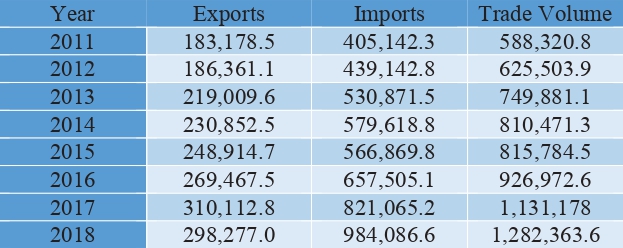

Table 2: Serbia and Turkey: Exports, Imports, and Trade Volume in USD

Source: Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia34

The above table clearly indicates a significant increase in trade exports and imports from 2011 to 2018. For example, in 2011 the total trade volume between Serbia and Turkey was $588,320.8 million while in 2018 it was $1,282,363.6 billion –a more than 50 percent increase in a span of seven years.

The above table also affirms the role of trilateral relations in bilateral trade relations between Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. For instance, in 2011, the total trade volume between Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina was 3,756,680,182 BAM, while in 2018 it was 3,979,404,388 BAM.

Table 3: Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia: Exports, Imports, and Trade Volume in BAM

Source: Foreign Trade Chamber of Bosnia and Herzegovina35

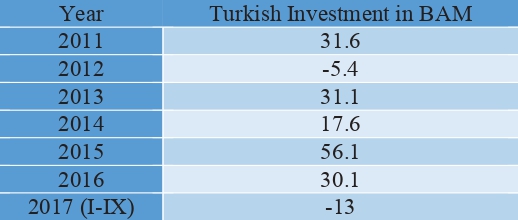

Trilateral relations also played a significant role in Turkish foreign direct investments (FDI) in Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, countries that have gradually become desirable investment destinations for Turkish companies. Since 2009, Turkey has gradually become an important economic and trade actor in the Balkans, including in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which Turkish companies consider a desirable investment destination.36 As early as 2009, Bosnia and Herzegovina received $61 million in Turkish foreign direct investment, while in 2015, they received €32.1 million in Turkish foreign direct investment.

Table 4: Turkish FDIs to Bosnia and Herzegovina in BAM

Source: The Central Bank of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Annual Report 201737

Table 5: Serbian FDIs to Bosnia and Herzegovina in BAM

Source: The Central Bank of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Annual Report 201738

Some of the leading Turkish companies in Bosnia and Herzegovina include Kastamonu Entegere-Natron-Hayat (paper company), Soda Sanayii-Soda Lukavac (chemical enterprise), Cengiz İnşaat (construction), Sezer Group (agriculture), and T. C. Ziraat Bankası-Turkish Ziraat Bank Bosnia.39 The Turkish government in cooperation with the Ziraat Bank and BBI Bank in 2012 approved credit in the amount of €100 million for the process of sustainably returning displaced people. In 2014, a new credit line of €50 million was introduced for “soft-loans” intended as credit for small and mid-sized companies in tourism, agriculture, and trade. Ziraat Bank offered loans to small and mid-sized companies for the realization of new projects and investments and to help decrease the rate of unemployment. In Serbia, more than 70 Turkish companies have a total investment volume of $113 million, mainly in textiles, food, communication, tourism, banking, and manufacture and construction. Turkish investors have made significant investments in the textile industry. Dzinsi, Birleşik, Jeanci, and Aster companies have their textile factories in Leskovac, Nis, Lazarevac, and Leban. Teklas Company, one of the leading Turkish manufacturers of car parts, opened a new plant and invested $711.35 million. In 2015, Halkbank acquired a 76 percent share of Čačanska Banka.40 According to Hürriyet Daily News, in 2017, there were 454 registered Turkish companies in Serbia.41

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, Turkey has also made investments in culture, education, and media. In this regard, it is worth mentioning investments by the Sarajevo Education Development Foundation (SEDEF), the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TİKA), and the Foundation for the Development of Relations with Bosnia and Herzegovina (BIGMEV). BIGMEV officially started its work in 2010, and began strengthening inter-state relations with Bosnia and Herzegovina. Its mission is to increase the number of Turkish investments in Bosnia, and strengthen trade from Bosnia to Turkey.

Turkey’s Vice President Oktay (C) and the Chairman of the House of Peoples of BiH Izetbegović (3rd R) attend the opening ceremony of 10th Sarajevo Business Forum on April 17, 2019. M.FATİH OĞRAŞ / AA Photo

Turkey and Bosnia and Herzegovina have historical and diplomatic relations rooted in deep historical and cultural ties. Such ties are institutionally maintained through the International University of Sarajevo, Yunus Emre Institute, and TİKA.42 Yunus Emre Institute, through its cultural centers in Sarajevo, Mostar, and Fojnica, has been fostering the cultural ties with Bosnia and Herzegovina mostly through language courses, seminars, conferences, concerts, art exhibitions, and literature nights. Because of such cooperation, famous Turkish singers, artists, writers, and actors have visited Bosnia and Herzegovina and participated in numerous projects and activities. Also due to the initiatives of the Yunus Emre Institute, children in elementary and primary schools in Zenica, Mostar, Sarajevo, and Bihac are currently learning the Turkish language as an elective course. TİKA has accomplished more than 700 projects in Bosnia; these include the restoration of the “Ferhadija Mosque” in Banja Luka, the “Mehmed Pasha Sokolovic Bridge” in Visegrad, the “Emperor’s Mosque” in Sarajevo, the “Old Bridge” in Mostar, and the “Blagaj Dervish House” in Blagaj-Mostar. In this regard, TİKA has contributed not only to cultural sustainability but also to the tourism sector in Bosnia and Herzegovina.43

Trilateral relations contributed to the signing of a large number of bilateral agreements on economic and trade cooperation between Turkey, Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, which in effect have created opportunities for investments in the tourism industry and other related industries

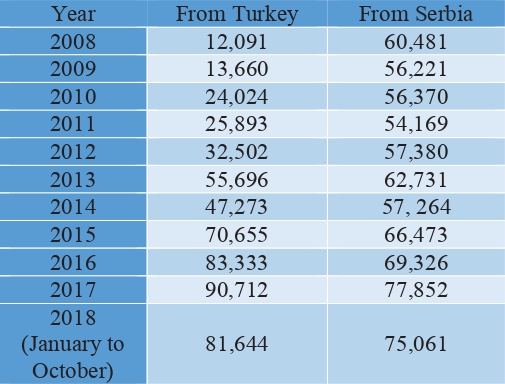

According to data obtained from the Agency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina, tourism between Turkey, Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina has significantly improved. Trilateral relations focusing on communication and transportation between Turkey, Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina have increased frequent flights between Sarajevo, Belgrade, and İstanbul. According to the table below, the number of visitors from Turkey traveling to Bosnia and Herzegovina has increased tremendously.44 In addition, trilateral relations contributed to the signing of a large number of bilateral agreements on economic and trade cooperation between Turkey, Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, which in effect have created opportunities for investments in the tourism industry and other related industries. Then, trilateral relations gradually led to the abolition of visas for citizens of Serbia, Turkey, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, which made traveling easier.

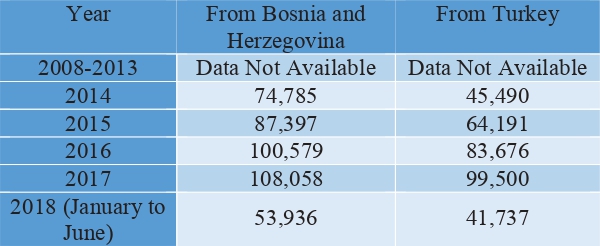

Table 6: Tourist Arrivals to Bosnia and Herzegovina

Source: Agency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina45

Table 7: Tourist Arrivals to Turkey

Source: Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Republic of Turkey46

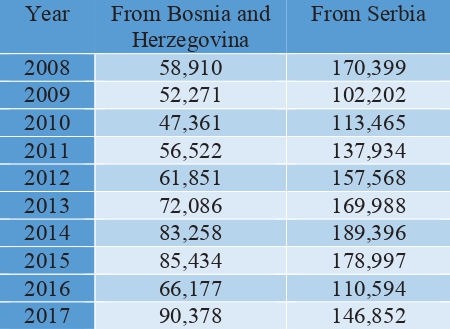

Table 8: Tourist Arrivals to Serbia

Source: Ministry of Trade, Tourism and Telecommunications47

Conclusion

The research paper at hand has attempted to examine to what extent trilateral relations as a model has been successful and how different actors at the presidential, ministry of foreign affairs, and ministry of economy and trade level have fostered proactive foreign policy and diplomacy. Have trilateral relations contributed toward more effective political, diplomatic, and economic and trade relations between Turkey, Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina? A chronological analysis of 2009-2018 tripartite diplomatic relations clearly indicates progress in terms of tackling questions of peace, reconciliation, prosperity, stability, and regional cooperation. At an early stage, trilateral relations promoted a culture of peace between Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, and constructive dealing with past and recent historical tragedies. From high-level state officials exchanging visits in 2009 and 2010 and the opening of embassies, trilateral relations from 2013-2018 emerged as an institutional platform for economic, trade, cultural, scientific, energy, infrastructure, transportation, and tourism cooperation between Turkey, Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The research clearly indicates that adopted declarations, agreements, models, mechanisms, and business summits and forums moved Turkey, Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina from mere discussions of peace and reconciliation to a phase of economic and trade cooperation. Thus, in comparison to trilateral relations at the presidential level, the ministries of foreign affairs and ministries of economy and trade were much more proactive and dynamic. These ministries adopted declarations and agreements, held summits and forums, and established commissions, programs, and action plans.

Furthermore, this research provided a significant assessment of trilateral relations in terms of contributions and drawbacks. The drawbacks noted here could be of significant use for upcoming trilateral relations agendas that should include hot questions such as tackling crimes against humanity, territorial integrity, the Serbia-Bosnia and Herzegovina border dispute, mediation of the Kosovo-Serbia dispute, the Russian position in the Balkans, NATO, FETÖ, and others. Finally, in order to assess the successfulness of trilateral relations, the research provided clear indicators of trade exchanges, foreign direct investment, the engagement of Turkish companies in Serbia and B&H, cultural exchanges, and tourism exchanges between Serbia, Turkey, and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Endnotes

- Part of this paper was presented at the 3rd International Research Congress on Social Sciences, International Balkan University, Skopje, North Macedonia, September 05-08, 2018.

- See the theoretical discussions on the trilateral relations model in Jan Hallenberg and Hakan Karlsson, Changing Transatlantic Security, (London and New York: Routledge, 2006), pp. 1-18.

- See, “Press Release Regarding the First Trilateral Meeting of the Ministers of Foreign Affairs of Turkey, Azerbaijan and Georgia,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Turkey, (June 5, 2012), retrieved from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/no_-155_-05-june-2012_-press-release-regarding-the-first-trilateral-meeting-of-the-ministers-of-foreign-affairs-of-turkey_-azerbaijan-and-georgia.en.mfa; “Turkey-Afghanistan-

Pakistan Trilateral Summit Was Held in Ankara,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Turkey, (February 13, 2014), retrieved from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/turkey_afghanistan_pakistan-trilateral-summit-

was-held-in-ankara.en.mfa; “Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu Hosted the Sixth Turkey-Azerbaijan-Iran Trilateral Foreign Ministers’ Meeting,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Turkey, (October 30, 2018) retrieved from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/turkiye-azerbaycan-iran-uclu-isbirligi-toplantisi_en.en.mfa; “Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu Hosts the Trilateral Meeting of Ministers of Foreign Affairs of Turkey, Poland and Romania,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Turkey, (April 19, 2019), retrieved from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/sayin-bakanimizin-turkiye-romanya-polonya-uclu-d%C4%B1sisleri-bakanlari-toplantisina-katilimi.en.mfa; “Joint Statement by the Ministers of Foreign Affairs of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the Russian Federation and the Republic of Turkey on Syria,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Turkey, (April 28, 2018), retrieved from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/joint-statement-by-the-ministers-of-foreign-affairs-of-the-islamic-republic-of-iran-the-russian-federation-and-the-republic-of-turkey-on-syria-moscow_en.en.mfa. - Nevenka Jeftić-Šarčević, “Zapadni Balkan u Projektu Turske Strate.ške Vizije,” Međunarodna Politika, Vol. 62, No. 4 (2010), pp. 691-714; Ziya Onis, “Multiple Faces of the New Turkish Foreign Policy: Underlying Dynamics and a Critique,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 13, No. 1 (2011), pp. 47-65.

- “Relations with the Balkan Region,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Turkey, retrieved from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/relations-with-the-balkan-region.en.mfa.

- Žarko Petrović and Dušan Reljić, “Turkish Interests and Involvement in the Western Balkans: A Score-Card,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 13, No. 3 (2011), pp. 160-165.

- “Turkey: A Factor of Regional Stability,” Helsinki Bulletin, No. 64 (May 2010), retrieved from http://helsinki.org.rs/doc/HB-No64.pdf .

- “The National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia (RS Official Gazette, No. 14/09 – revised text),” National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia, (March 1, 2010), retrieved from http://www.parlament.gov.rs/upload/archive/files/eng/pdf/2010/deklaracija%20o%20srebrenici%20ENG.pdf; Aslı Fatma Keltikli, “Turkey and the Western Balkans During the AKP Period,” Avrasya Etüdleri, Vol. 44, No. 2 (2013), pp. 95-96.

- Petrović and Reljić, “Turkish Interests and Involvement in the Western Balkans: A Score-Card,” pp. 159-172.

- Bulent Sarper Ağır and Murat Necip Arman, “Turkish Foreign Policy towards the Western Balkans in the Post-Cold War Era: Political and Security Dimensions,” in Demir Sertif (ed.), Turkey’s Foreign Policy and Security Perspectives in the 21st Century: Prospects and Challenges, (Boca Raton, Florida: Brown Walker Press, 2016), p. 158; Keltikli, “Turkey and the Western Balkans During the AKP Period,” p. 96.

- “Turkey: A Factor of Regional Stability.”

- Hajrudin Somun, “Turkish Foreign Policy in the Balkans and ‘Neo-Ottomanism:’ A Personal Account,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 13, No. 3 (2011), pp. 33-41; Marija Mitrovic, “Turkish Foreign Policy towards the Balkans: The Influence of Traditional Determinants on Davutoğlu’s Conception of Turkey-Balkan Relations,” GeTMA Working Paper, No. 10 (2014), pp. 39-57; Dimitar Bechev, “Turkey in Balkans: Taking a Broader View,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 14, No. 1 (2012), p. 141.

- “Ankara Summit Declaration,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Turkey, (May 15, 2013), retrieved from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/ankara-summit-declaration-adopted-at-the-conclusion-of-turkey-_-bosnia-herzegovina-_-serbia-trilateral-summit_-15-may-2013_-ankara.en.mfa; Dodje Pavlovic, “The Future of the Trilateral Cooperation among Bosnia and Herzegovina, Turkey and Serbia,” in Current Turkey-Serbia Relations, (İstanbul: SAM, 2015), pp. 20-21; Erhan Türbedar, “Turkey’s New Activism in the Western Balkans,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 13, No. 3 (2011), pp. 139-158.

- Birgül Demirtaş, “Reconsidering Turkey’s Balkans Ties: Opportunities and Limitations,” in Ercan Gözen Pınar (ed.), Turkish Foreign Policy: International Relations, Legality and Global Reach, (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), pp. 136-143.

- “Erdogan Vows to Help Build Serbia-Bosnia Hightway,” Balkan Insight, (January 29, 2018), retrieved from https://balkaninsight.com/2018/01/29/turkey-s-erdogan-promises-to-help-build-serbia-bosnia-highway-01-29-2018/.

- Maja Zivanovic, “Tight Security Surrounds Turkey’s Erdogan in Serbia,” Balkan Insight, (October 10, 2017), retrieved from https://balkaninsight.com/2017/10/10/high-security-measures-follows-erdogan-s-visit-to-serbia-10-09-2017/.

- Adam Balcer, “Turkey as a Stakeholder and Contributor to Regional Security in the Western Balkans,” in Ebru Canan Sokullu (ed.), Debating Security in Turkey: Challenges and Changes in the Twenty-First Century, (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2012), p. 228; İnan Rüma, “Turkish Foreign Policy towards the Balkans: Overestimated Change within Underestimated Continuity,” in Zeynep Özden Oktav (ed.), Turkey in the 21st Century: Quest for a New Foreign Policy, (London and New York: Routledge, 2016), pp. 144-145.

- “Press Release Regarding the Visit of H.E. Mr. Ahmet Davutoğlu, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Turkey, to Bosnia and Herzegovina on the Occasion of the Trilateral Consultation Meeting of the Ministers of Foreign Affairs of Turkey, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Turkey, (May 7, 2013), retrieved from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/no_-129_-7-may-2013_-press-release-regarding-the-visit-of-h_e_-mr_-ahmet-davuto%C4%9Flu.en.mfa; “Turkey-Serbia-Bosnia and Herzegovina Foreign Ministers Meet in New York,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Turkey, (September 24, 2013), retrieved from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/turkey_serbia_bosnia-and-herzegovina-foreign-ministers-meet-in-new-york.en.mfa.

- “Dacic: Serbia Is Partner to UN Members Striving for Peace,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Serbia, (September 30, 2014), retrieved from http://www.mfa.rs/en/press-service/daily-news?year=2015&month=9&modid=62.

- “Dacic: Serbia Is Partner to UN Members Striving for Peace.”

- “Decleration on Economic, Trade Cooperation of Serbia, BiH, and Turkey Signed,” Ministry of Trade, Tourism and Telecommunications of Serbia, (May 14, 2013), retrieved from http://mtt.gov.rs/en/releases-and-announcements/declaration-on-economic-trade-cooperation-of-serbia-bih-and-turkey-signed/.

- Foreign Trade Chamber of Bosnia and Herzegovina, retrieved from http://www.mvteo.gov.ba/publication/read/sarovi%C4%87--ljaji%C4%87-i-%C3%A7a%C4%9Flayan-potpisali--deklaraciju-o-ekonomskoj-i-trgovinskoj-saradnji-izme%C4%91u-bosne.

- Foreign Trade Chamber of Bosnia and Herzegovina, retrieved from http://www.mvteo.gov.ba/publication/read/trilateralni-sastanak-bih--srbije-i-turske-unaprijedio-saradnju.

- “Representatives of the Turkish, Serbian and Bosnian Business Community Hold Trilateral Business Forum in İstanbul,” Foreign Economic Relations Board, (October 26, 2016), retrieved from https://www.deik.org.tr/press-releases-representatives-of-the-turkish-serbian-and-bosnian-business-community-hold-trilateral-business-forum-in-istanbul.

- “Serbia,” Republic of Turkey Ministry of Trade, (September 6, 2018), retrieved from https://trade.gov.tr/free-trade-agreements/serbia.

- “Serbia, Turkey Sign Agreements to Boost Trade,” Balkan Insight, (October 10, 2017), retrieved from https://balkaninsight.com/2017/10/10/serbia-turkey-sign-agreements-to-boost-trade-10-11-2017/.

- Keltikli, “Turkey and the Western Balkans During the AKP Period,” p. 98.

- “New Trade Agreement Signed Between Serbia and Turkey,” Republic of Turkey Ministry of Trade, (January 30, 2018), retrieved from http://mtt.gov.rs/en/releases-and-announcements/new-free-trade-agreement-signed-between-serbia-and-turkey/.

- Pavlovic, “The Future of the Trilateral Cooperation among Bosnia and Herzegovina, Turkey and Serbia,” pp. 141-144.

- “IZVOZ: Turska 2011,” Foreign Trade Chamber of Bosnia and Herzegovina, retrieved from http://komorabih.ba/vanjskotrgovinska-spoljnotrgovinska-razmjena/?drzava=Turska&godina1=2018&po_drzavi=PRIKA%C5%BDI; http://komorabih.ba/vanjskotrgovinska-spoljnotrgovinska-razmjena/?drzava=Turska&godina1=2011&po_drzavi=PRIKA%C5%BDI.

- “Erdoğan’s Visit to Stimulate Investments, Trade with Bosnia,” Daily Sabah, (May 23, 2018), retrieved from https://www.dailysabah.com/economy/2018/05/24/erdogans-visit-to-stimulate-investments-trade-with-bosnia.

- “IZVOZ: Turska 2018,” Foreign Trade Chamber of Bosnia and Herzegovina, retrieved from http://komorabih.ba/vanjskotrgovinska-spoljnotrgovinska-razmjena/?drzava=Turska&godina1=2018&po_drzavi=PRIKA%C5%BDI.

- Mustafa Çakır, “An Economic Analysis of the Relationship between Turkey and the Balkan Countries,” Adam Akademi, Vol. 4, No. 2 (2014), pp. 79-82.

- “Country of Destination Rank/Origin, by Value of Exports/Imports,” Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia, (February 6, 2019), retrieved from http://data.stat.gov.rs/Home/Result/170401?languageCode=en-US.

- “IZVOZ: Srbija 2018,” Foreign Trade Chamber of Bosnia and Herzegovina, retrieved from http://komorabih.ba/vanjskotrgovinska-spoljnotrgovinska-razmjena/?drzava=Srbija&godina1=2018&po_drzavi=PRIKA%C5%BDI.

- Çakır, “An Economic Analysis of the Relationship between Turkey and the Balkan Countries,” pp. 82-85.

- “Annual Report 2017,” The Central Bank of Bosnia and Herzegovina, (2017), retrieved from https://cbbh.ba/content/DownloadAttachment/?id=8ed74fba-a1b4-4e51-951c-f835556f9970&langTag=en

- “Annual Report 2017.”

- Mehmed Ganic and Azra Brankovic, Bosnia and Herzegovinian’s Commercial and Economic Relations with Turkey: The Status of BiH’s Economy and Recommendations for the Future, (Sarajevo: IUS, 2016), pp. 50-65.

- Muhidin Mulalic and Ahmed Kulanic, “Perceptions of Turkish Cultural Diplomacy in Bosnia and Herzegovina,” in Muhidin Mulalic, Nudzejma Obralic, Almasa Mulalic, and Emina Jeleskovic, (eds.), Education, Culture and Identity: The Future of Humanities, Education and Creative Industries, (Sarajevo: IUS, 2016), pp. 494-508.

- Keltikli, “Turkey and the Western Balkans during the AKP Period,” pp. 100-102.

- Muhidin Mulalic, “Higher Education in Bosnia and Herzegovina: A Path towards Economic Development,” in Yücel Oğurlu and Ahmed Kulanic (eds.), Bosnia and Herzegovina: Law, Society and Politics, (Sarajevo: International University of Sarajevo, 2016), p. 188.

- Elif Nuroğlu, “TİKA and Its Political and Socio-Economic Role in the Balkans,” in Muhidin Mulalic, Hasan Korkut, and Elif Nuroglu (eds.), Turkish-Balkans Relations: The Future Prospects of Cultural, Political and Economic Transformations and Relations, (İstanbul: Tasam Publication, 2013), pp. 279-298.

- “Poslovne Statistike: Turizam,” Agency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina, retrieved from http://www.bhas.ba/index.php?option=com_publikacija&view=publikacija_pregled&ids=3&id=16&n=Turizam.

- “Poslovne Statistike: Turizam.”

- “Number of Arriving-Departing Visitors, Foreigners and Citizens,” Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Republic of Turkey, retrieved from http://www.kultur.gov.tr/EN-153018/number-of-arriving-departing-visitors-foreigners-and-ci-.html; “Bordr Statistics, 2017,” Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Republic of Turkey, retrieved from http://www.kultur.gov.tr/Eklenti/59409,border-statistics-2017xlsx.xlsx?0.

- Ministry of Trade, Tourism and Telecommunications of Serbia, retrieved from http://mtt.gov.rs/sektori/sektor-za-turizam/korisne-informacije-turisticki-promet-srbija-kategorizacija/; Ministry of Trade, Tourism and Telecommunications of Serbia, retrieved from http://mtt.gov.rs/download/VI%20-%202018.doc.