Introduction

The imploding political stability and multiplying security threats over a vast geography, from the greater Middle East to Europe’s gates, have set in motion a global tectonic shift.1 A refugee crisis of biblical proportions, the problem of ISIS, increased terrorist attacks targeting urban populations, and the mushrooming of “failed states” in the region suggest no single nation or community is immune from the tightening grip of insecurity around the central tenets of humanity. Turkey is not immune from these challenges and security risks; on the contrary, it is at the epicenter of this global shift. Both its domestic affairs and foreign policy are exposed to these developments. While expectations vis-à-vis Turkey’s role and involvement in the Middle East increase, challenges originating from the Middle East confront Turkey more than ever before. Turkey’s domestic and foreign policy choices will shape not only the future of this region but also the effectiveness of any international, concerted effort for enduring peace and stability.

In order to respond more effectively to these unprecedented challenges and security risks, Turkish foreign policy has been radically reset over the last two years. While its proactive mode of operation since 2002 has remained, its vision, its identity, and its strategy have evolved. The radical reset of Turkish foreign policy since 2015, as will be analyzed in detail throughout this paper, involves a rupture rather than continuity with the 2002-2010/15 “Davutoğlu era.”2 I argue that over the last two years we have been witnessing not only a foreign policy reset but also the emergence of a new Turkish foreign policy whose proactive nature and main principles are shaped by what I call proactive “moral realism,” which combines hard power-based military assertiveness and humanitarian norms.3

In the post-Davutoğlu era, foreign policy in Turkey has emerged with proactive moral realism as its main motto and modus operandi

In the post-Davutoğlu era, foreign policy in Turkey has emerged with proactive moral realism as its main motto and modus operandi. Moral realism should be seen not as a conjectural choice that Turkey has made to respond to security risks; on the contrary, it seems to have the potential to define its foreign policy in the years to come. Unlike the 2002-2010 Davutoğlu era, in which proactive foreign policy articulated soft power coupled with civilizational multilateralism, moral realism is a strategic choice made in order to achieve three goals simultaneously: to maintain proactivism; to continue to promote the primacy of humanitarian norms and moral responsibility to protect human lives; and to respond effectively and assertively to security risks and challenges through hard power.4 Since 2015, with its humanitarian approach to the refugee crisis and its military involvement in Syria to fight against both ISIS and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party and its Syrian counterpart, the Democratic Union Party (PKK/PYD/YPG), Turkey has been able to combine humanitarianism and realism, which I call moral realism. In fact, among the many great and middle power actors involved in Syria and Iraq, from America and Russia to Iran and Saudi Arabia, it is only Turkey that has implemented moral realism in its proactive engagements. As our globalizing world continues to be more crisis-ridden, as geopolitical power games among great actors continue to shape world politics, and as interest rather than norm continues to define state behavior, proactive moral realism seems to endure in defining and shaping Turkish foreign policy and its regional and global engagements.5

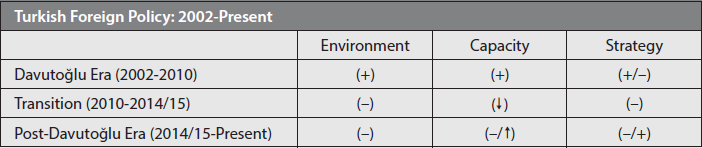

To substantiate this argument, I will map the ways in which foreign policy has evolved since the beginning of the AK Party rule in 2002. In doing so, I will explore continuities and ruptures in identity and behavior. There are three conditions that must be met in order for a country’s engagement in proactive foreign policy to be successful: (a) there has to be a suitable environment for it; (b) there has to be capacity to implement it effectively; and (c) there has to be a formulated strategy. In what follows, I will map the evolution of Turkish foreign policy since 2002 by focusing on these three benchmarks: environment, capacity, and strategy.

Environment: Turkey as a “Pivotal State/Regional Power”

Two decades ago in his influential work The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives, Zbigniew Brzezinski suggests:

Gravely increasing the instability of the Eurasian Balkans and making the situation potentially much more explosive is the fact that two of the adjoining major nation-states, each with a historically imperial, cultural, religious, and economic interest in the region –namely, Turkey and Iran– are themselves volatile in their geopolitical orientation and are internally potentially vulnerable. Were these two states to become destabilized, it is quite likely that the entire region would be plunged into massive disorder, with the ongoing ethnic and territorial conflicts spinning out of control and the region’s already delicate balance of power severely disrupted. Accordingly, Turkey and Iran are not only important geostrategic players but are also geopolitical pivots, whose own internal condition is of critical importance to the fate of the region. Both are middle-sized powers, with strong regional aspirations and a sense of their historical significance.6

Since Brzezinski penned this description of Turkey in 1997, significant changes and transformations in world politics have occurred –from global terror to Arab Uprisings, from human tragedy to failed states, from global economic crisis to global climate change– giving rise to global turmoil and multiple crises of globalization, as well as generating important impacts on foreign policy. Yet, Brzezinski’s diagnostic statement about Turkey, emphasizing both its regional power identity and the importance of domestic stability for the sustainability of this role, has remained true. Turkey has become a ‘geopolitical pivot’ and ‘regional power’ in our globalizing world. It has been initiating a proactive, multi-dimensional, and constructive foreign policy in many areas, ranging from contributing to peace and stability in the Middle East to playing an active role in countering terrorism and extremism, from becoming a new “energy hub.” While acting as an effective humanitarian state aiming at managing the recent refugee crisis, it has been making a significant contribution to the enhancement and betterment of the human condition where development assistance is needed.

Iraqi Prime Minister Haidar al-Abadi meets with his Turkish counterpart Binali Yıldırım in Baghdad on January 7, 2017. | AFP PHOTO

Iraqi Prime Minister Haidar al-Abadi meets with his Turkish counterpart Binali Yıldırım in Baghdad on January 7, 2017. | AFP PHOTO

As a pivotal state/regional power, Turkey’s foreign policy has been dynamic, transforming and modifying based on its environment. Since the September 11, 2001 terror attacks, Turkey has been at the center of global and regional challenges. With its long borders with Syria and Iraq and geographical bridge between East and West, it has been affected by global turmoil. Yet at the same time, it has been seen as a pivot whose role is crucial to tackling such challenges effectively. Significant turning points in this crisis-ridden environment impacted Turkish foreign policy. The September 11 terrorist attacks, the 2008 global economic crisis, the beginning of the Arab Uprisings in 2010, and the increasing power of ISIS in Syria and Iraq since 2014 have produced unprecedented security challenges, forcing Turkish foreign policy to reset itself.

Since 2002, it is possible to analyze and categorize Turkish foreign policy within three periods. The first period starts in 2002 and continues until 2010, in which the environment was framed by the September 11 attacks and American neoconservative global war on terror. Turkish foreign policy was shaped by soft power and active globalization. In this period, the environment was suitable for Turkey’s proactivity –insofar as its ability to balance Islam, democracy and secularism had given rise to an upsurge of interest both regionally and globally. In this period, Ahmet Davutoğlu’s concept of “strategic depth”7 and his civilizational, realist thinking of regional and global relations, coupled with the EU anchor, defined the basic parameters of foreign policy. This period ended with the beginning of the Arab Spring, i.e., the Arab Uprising in Tunisia and Egypt in 2010, where a strong societal demand arose for regime change in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Starting in Tunisia and moving rapidly to Egypt, the ordinary people of these countries organized from the bottom up an effective protest movement demanding the replacement of the existing authoritarian regimes and rentier states with a more democratic, accountable, transparent, uncorrupt, and economic system of governance based on inclusive institutions and equal citizenship. The Arab Uprisings, while initially bringing hope to the region, have instead paved the wave for internal wars, human tragedy and despair. The military coup in Egypt and the internal war in Syria ended the possibility of transformation in the region. Instead the region was taken hostage by power games and self-interest.8 In this period, globalization was confronted by multiple crises, risks and challenges –from economic crisis to climate change, from wars to violence, from poverty to inequality. The Arab Uprisings transformed into internal wars and geopolitical power games at a time of global turmoil and the multiple crises of globalization.9 Turkey was not immune from this radical change, creating a negative environment within which to operate its foreign policy. The period between 2010-2014/5 impacted proactive foreign policy immensely, giving rise to the need for its reset. Yet, this reorganization was not realized until August 2015, in which Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s tenure as prime minister came to a close and he ascended to a new position of power and influence, that of the Turkish presidency. It was further consolidated as the tenure of Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu ended and Binali Yıldırım became both the leader of the AK Party and the new Prime Minister of Turkey.

The September 11 terrorist attacks, the 2008 global economic crisis, the beginning of the Arab Uprisings in 2010, and the increasing power of ISIS in Syria and Iraq since 2014 have produced unprecedented security challenges, forcing Turkish foreign policy to reset itself

Since 2015, the environment has been negative; yet at the same time, Turkey has been able to confront a set of significant security risks. Escalating conflict and instability in the region within the deepening global turmoil made it necessary, if not imperative, to adjust Turkish foreign policy. These unprecedented challenges producing existential threats to the national security of Turkey can be listed as follows: (i) the profound refugee influx and crisis, whose numbers have exceeded six million regionally; (ii) an ongoing war against ISIS, which can be defined as ‘more than a terror organization, less than a state’ –a brutal and inhumane terror organization on the one hand and a self-proclaimed Islamic state; (iii) the ‘failed state’ problem in Syria and Iraq and its widening throughout the MENA; (iv) the intensified geopolitical power games staged by great powers to strengthen their hegemonic positions, to exert their influence and to maximize their interests; (v) the emergence of new forms of war and violence varying from proxy wars to suicide bombers; and (vi) the increasing power of sectarian identity claims widening and deepening the devastating human tragedy to an unimaginable degree.10 These factors have together made the region a space of instability and insecurity, where multiple crises-ridden challenges intersect.

It is the possibility of constructing a state in Syria and Iraq that has constituted the PKK’s primary motive, not the cultural identity rights of the Kurds in Turkey

With its long borders with Syria and Iraq, its pivotal position and its hegemonic power capabilities, Turkey is situated at the heart of these challenges. In particular, the refugee crisis, ISIS, and the failed state problem affect Turkey and its security directly. The refugee influx in Turkey involves almost 3.5 million people. While applying unconditional hospitality to refugees, Turkey needs to provide humanitarian-based governance policies, varying from educational and economic needs to establishing necessary safety and security mechanisms. In doing so, the Turkish state has spent over $25 billion in the last three years; yet, further efforts towards this goal can be undertaken. In addition, the Turkish army has been the most effective and active among the coalition forces fighting ISIS on Turkey’s southern border, as well as in Syria. Not only is Turkey in need of securing its borders against ISIS, it also has fought against it to contribute to regional stability. Turkey successfully initiated “Operation Euphrates Shield,” which began at the end of August 2016, to eradicate the presence and power of ISIS in Syria and Iraq. Yet, the human and social cost of this fight has been very high with many innocent lives have been lost and fear and ontological insecurity have widened as a result of ISIS’ brutal terrorist attacks in Turkey.

It should be noted that both the refugee and the ISIS crisis have been triggered by the failed state problem in Syria and Iraq. Neither Syria nor Iraq is capable of controlling their internal affairs and borders.11 Both are confronted by internal wars, violence and the risk of disintegration. Both are in need of reconstruction and efforts to regain sovereignty. As failed states, they are incapable of and lack the capacity to govern their societies as territorially sovereign actors. While ISIS has been exerting its influence and control in these countries, Syria and Iraq have become a zone of existential insecurity giving rise to a massive flow of refugees.

Moreover, the impacts of these crises and the failed state problem have multiplied and been complicated by two critical domestic challenges, namely the PKK and the July 15 coup attempt. These challenges are designed to destabilize Turkey, to challenge the capacity of the AK Party to govern and provide security for Turkish citizens, and to delimit Turkey’s foreign policy engagements and involvement, especially in the Middle East. Over the last two years, Turkey has witnessed the end of the peace process to disarm the PKK and a window of possibility for a democratic solution to the Kurdish problem and, more gravely, the fast and deadly escalation of terror and conflict. Turkey has been the target of terror attacks not only by ISIS but also by the PKK and its offshoot, the Kurdistan Freedom Falcons (TAK). The PKK has initiated a number of deadly terrorist attacks targeting both civilians and security forces taking in the centers of Ankara and İstanbul. As the debates on these attacks have indicated, it is the possibility of constructing a state in Syria and Iraq that has constituted the PKK’s primary motive, not the cultural identity rights of the Kurds in Turkey. The failed state problem is one of the main factors contributing to the possibility of an independent Kurdish state. It is in this context that the escalation of conflict in Turkey since 2015 is directly related to Syria and Iraq.12

On the night of July 15, 2016, Turkey was shocked by an abrupt, outrageous, and bloody coup attempt organized by the Gülenist Terror Organization (FETÖ). This was an attack not only on President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the AK Party government but the Grand National Assembly and Turkish citizens. It was a shocking attack on Turkey, the diversity of the Turkish people, its democracy and secular modernity. Ultimately, the coup attempt failed; however, an estimated 248 civilians were killed and 1,440 civilians were wounded. Regardless of ethnic, religious, cultural, class and lifestyle differences, Turkish citizens were united against the coup. From political parties to economic actors, from media to civil society organizations, Turks stood strong. As a result, the attempt was unsuccessful. The unity displayed by Turkish citizens should be welcomed and celebrated in the name of protecting democracy over military rule, living together rather than polarization, and opening a window of opportunity for a new constitution based on equal citizenship and inclusive institutions. Nevertheless, post-coup Turkey is at a crossroads in terms of democracy. With what has come to be called ‘the post-coup massive purge’ and the declaration of a state of emergency framing governance today, there is increasing skepticism on the future of democracy in Turkey.

Table 1: Turkish Foreign Policy: 2002-Present

As Table 1 indicates, a crucial strategic choice was made in 2015 to respond to existential security risks, giving rise to a new, proactive foreign policy organized around a set of fresh parameters in terms of capacity and strategy. The Davutoğlu era, with its emphasis on strategic depth, finally ended in 2014/15, and a new foreign policy has begun to emerge that has been shaped by proactive moral realism.

Capacity and Strategy: Proactive Moral Realism

What has changed in Turkish foreign policy since 2002? In what way has the changing environment impacted Turkish foreign policy? How has Turkish foreign policy responded to this changing environment? In other words, what have been the elements of continuity and rupture in the capacity and strategy of Turkish foreign policy?

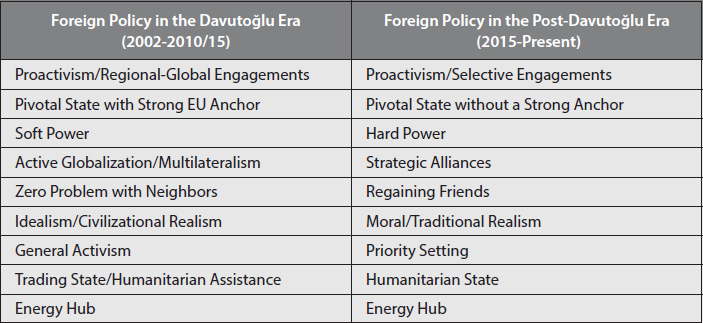

Research on Turkey13 and its proactive foreign policy since 2000 –on which this paper was developed– indicates that there are at least nine areas worth emphasizing in this context.

Since 2002, foreign policy in Turkey was, and continues to remain, proactive and a return to bilateralism, caution, and passive foreign policy of the Cold War years is unlikely. Turkey has been, and likely will continue to be, active, engaging, and assertive both regionally and globally. Yet, while this proactivity in 2002-2010 was more multi-layered, multi-actor, and multi-dimensional, as well as more regionally and globally engaging, the present nature of proactivity seems to be more focused, selective, and globally limited. Today, the nation’s regional and global engagements focus on Syria and Iraq, as well as on Africa, and operate on the basis of the priority of security concerns and humanitarian norms.

Since 2002, the perception of Turkey as a pivotal state/regional power has remained. Despite problems and tensions, Turkey has coexisted with Islam, economic dynamism, modernity, and secular democracy across a largely Muslim population with a dual identity as a Middle Eastern and European country. Its long borders with Syria and Iraq –and its proactive foreign policy has seen it act as a pivotal state/regional power in an uncertain, insecure and globalizing world. Turkey is the only country that can talk both to the ‘West and the Rest’ –to Western leaders and Middle Eastern leaders and to the North and the South. Turkey is also the only country that can play a crucial role in managing the recent refugee crisis and at the same time eradicate or minimize the influence and power of ISIS in the region. This means that even though problems of trust and cooperation have emerged between Turkey and the West in recent years, expectations of Turkey by the West and international community of its role in creating the possibility of return to normality and order in the region has remained. These expectations have increased in 2017 with respect to the war against ISIS.

From the war against ISIS to the creation of order and stability, from managing the refugee crisis to state building, the pivotal role of Turkey was perceived more in security terms rather than in terms of economy, culture, identity and democracy

Turkish foreign policy has undergone a shift from soft power to hard power. Turkish foreign policy between 2002 and 2010 was framed by the use of what has come to be called “soft power.” Turkey’s proactivity was implemented in the areas of economy, culture, identity, diplomacy, humanitarianism and modernity. As a modern nation-state formation with a secular, democratic government, largely Muslim population, dynamic economy and a highly mobile, young and entrepreneurial population, Turkey was a model country or inspiration for the future of democracy, stability, and peace in the Middle East and Muslim world in general. These factors combined with Turkey’s active globalization and proactive foreign policy gave rise to its regional and global perception as a trading state. A deepening relationship with the EU and the beginning of full accession negotiations in the 2000-2005 period, resulted in a positive perception, especially among economic and foreign policy actors, of Turkey as a unique case in the process of European integration with the ability to help Europe to become a multicultural and cosmopolitan model for regional integration. In this reading, Turkey could become a space for the creation of a post-territorial community on the basis of post-national and democratic citizenship and a global actor with the capacity to contribute to the emergence of democratic global governance. Finally, the nation’s active and constituting role in the creation of the alliance of civilizations to challenge the clash of civilization thesis was regionally and globally welcomed. In all areas, Turkey was perceived regionally and globally as a soft power whose role and place in regional and global peace and stability is of the utmost importance. However, since 2010, all of Turkey’s soft power capacities have declined significantly. Instead, in ways similar to Cold War years, Turkey’s hard power capacities have become more visible in bilateral and international talks. From the war against ISIS to the creation of order and stability, from managing the refugee crisis to state building, the pivotal role of Turkey was perceived more in security terms rather than in terms of economy, culture, identity and democracy. Turkey’s military and geopolitical hard power capacities began to draw attention. Turkey’s strategic “buffer state” capacity to contain ISIS, to manage the refugee crisis, and to contain Iran and its regional power aspirations have become more important than its soft power capacities.

In terms of strategic choice, Turkey’s 2002-2010 strategy of active globalization through multilateralism has significantly declined and been replaced by the establishment of, and involvement in strategic security alliances. The deepening of the global turmoil, the increasing regional instability and insecurity in the MENA and the failed state problems in Syria and Iraq, are environmental conditioning factors that have compelled Turkey to adjust its strategic choices to secure its survival in anarchy. Since 2015, especially since the last quarter of 2016, Turkey has found a place at the table of the geopolitical power games through strategic alliance building starting with Russia, the U.S. and Saudi Arabia. The shift from soft power to hard power has emphasized the strategic importance of alliances in foreign policy making.

The main principle of the 2002-2010 period –zero problems with neighbors– ended in 2015 and has been replaced by the policy of regaining friends. As new Prime Minister Binali Yıldırım announced at the end of 2015, “Turkey will make a significant effort to regain old friends and make new friends,” and crucial steps were made to normalize relations with Israel and Russia. The government also made efforts to improve relations with the Gulf region starting with Saudi Arabia and, most recently, with the Trump administration. The bilateral relationship between with Russia seem to have gained momentum in 2017, which has contributed immensely to the success of Turkey’s fight against ISIS and its effort to prevent cantonal state-like development in Syria.

Turkey has not only contributed to global security but also strengthened new human-based norms of democratic global governance

There was also a shift from “civilizationalist realism” in the 2002-2010 period, whose basic principles can be found in Davutoğlu’s elaboration of strategic depth, to “moral realism” in the use of hard power. This new foreign policy and its proactivity is much more security-oriented, prioritizing security concerns over economy and culture. Turkey’s engagement with Syria and Iraq concurs with the traditional realist of international relations, suggesting that in an anarchic environment, states become skeptical of other states’ behavior, thus attempting to increase their hard power in order to secure their own survival.14 Turkey’s Operation Euphrates Shield is an illustrative example of such realist strategic thinking. Since 2015, we have seen the increasing presence of realism in foreign policy making in terms of both discourse and strategy. However, it differs from traditional realism in that it pays scant attention to humanitarian norms and operates by articulating realism with humanitarianism –that is, moral realism. It places a strong emphasis on security and is shaped by realist strategic thinking, by which it becomes proactive and assertive in its regional engagements, with special emphasis placed on morality and the importance of humanitarian norms. It locates itself outside the geopolitical power games played by great and regional powers and legitimizes its proactivity with reference to its efforts to manage the refugee crisis and stop the human tragedy in the region.

There is a significant shift from the “general activism” of the 2002-2010 period to “priority setting” to make strategic choices in terms of regional engagements more realistic and effective. Turkish foreign policy in the post-Davutoğlu era is and will be more about priorities and less about general activism. Moral realism and the use of hard power goes hand-in-hand with priority setting, both of which constitute the growing importance of strategy and making the right strategic choices to achieve the desired outcomes.

The deepening global turmoil and multiple crises of globalization has begun to generate significant challenges to global security and require global solutions. Turkey has made what has come to be known as humanitarian intervention and humanitarian assistance one of the central concerns of its international relations. Since 2002, with soft power and a proactive actor in foreign policy, Turkey has also been a regional and global force in peacekeeping and humanitarian operations. It has become one of the key global humanitarian actors of world politics.15 Turkey has increasingly been involved in humanitarian assistance in different regions of the world, and in doing so it has not only contributed to global security but also strengthened new human-based norms of democratic global governance. Turkey’s civilian humanitarian aid to Palestinians in Gaza, its involvement in Afghanistan, and its recent engagement in Somalia and Sudan are just some examples of peacekeeping contributions in different parts of the world. Turkey’s humanitarian role has increased since 2014/15 as it has provided unconditional hospitality and welcomed innocent civilians who have been forced to leave their homes as the subjects of forced displacement. Home to almost 3.5 million refugees, Turkey is a significant humanitarian actor dealing effectively with the refugee crisis.

Furthermore, although Turkey does not produce oil or natural gas, it has recently begun to act as an energy hub for the transmission of natural gas between the Middle East, the post-Soviet Republics and Europe. An increasing interest in the role of Turkey in global energy politics has emerged. Since 2002, energy has been integral to Turkey’s proactive foreign policy and its regional and global engagements. A country with significant energy dependency on Russia and Iran, it has begun to act as a strategic hub in the arena of energy politics. Moreover, as energy politics and its role in globalization has increased, this energy hub identity has begun to generate significant impacts on Turkish foreign policy, especially with respect to Turkey-EU, Turkey-Russia, and Turkey-U.S. relations.

These nine parameters influence capacity and strategy, delineate continuities and ruptures, as well as highlighting where Turkish foreign policy in the post-Davutoğlu era gains novelty and specificity. They also give meaning to Turkey’s pivotal state/regional power foreign policy identity.

Table 2: Turkish Foreign Policy in the Davutoğlu and Post-Davutoğlu Era

As Table 2 reveals, it is possible to define foreign policy in the post-Davutoğlu era as an emerging reality shaping Turkey’s pivotal state/regional power identity through a set of new capacity and strategy based parameters, namely those of selective proactivity, hard power, regaining friends, moral realism, priority setting, humanitarian state and energy hub. All of these parameters seem to have been chosen rationally in order to strengthen Turkey’s responses to serious regional security risks and unprecedented global challenges. As the environment has become more and more negative, risky and uncertain, Turkey has been compelled to adjust its foreign policy and its proactivity.

Since 2015, with its humanitarian approach to the refugee crisis and its military involvement in Syria to fight against both ISIS and the PKK/PYD/YPG, Turkey has been able to combine humanitarianism and realism

It should be pointed out that Table 2 also reveals that since 2010, Turkish foreign policy has lost a number of very important and valuable qualities that had previously created an upsurge of interest and attraction to Turkey both regionally and globally. While Turkey was perceived as a model, a point of inspiration, or a beacon between 2000 and 2010, unfortunately, all of these model-based qualities have now diminished. Likewise, in the same period, it was also perceived as a significant and successful trading state with its active globalization and multilateral institutional arrangements, as well as economic dynamism and an active, creative and entrepreneurial culture. There is now a significant degree of decline in Turkey’s trading state capacity. Furthermore, Turkey was a promising mediator dealing effectively with regional and global conflicts. There was an UN-based effort to make İstanbul a regional hub for conflict resolution and mediation. This is now frozen. It is true that the deepening of global turmoil and multiple crises of globalization together have generated a negative environment that makes it very difficult to carry these parameters and maintain a soft power capacity. Nevertheless, to revitalize or regain these capacities should be one of the priorities of moral realism. Without such capacity, prioritizing security in foreign policy making might risk sustainability. Decision makers and influencers in Turkey should bear in mind that soft power capacity is of the utmost importance not only in making proactive moral realism sustainable but also in bringing back the positive regional and global image of Turkey. As I have argued elsewhere, unless this is done, there is a risk that Turkey could turn into a buffer state, with its foreign policy shaped purely by security concerns, whose main role is to contain ISIS, refugees, and Iran.16

Conclusion: Articulating Proactive Moral Realism with

Democratic Reform

Our globalizing world is facing multiple crises amidst deepening global turmoil. Responding to these multiple crises is the overall aim of each and every state’s foreign policy. The foreign policy reset to proactive moral realism has been Turkey’s response not only to secure itself vis-à-vis serious regional and global security risks but also to contribute to the creation of a much needed order and stability in the MENA – starting with Syria and Iraq. In doing so, new policies have tried to combine assertive and hard power-based regional engagements with unconditional hospitality. Turkey has reached out to innocent people forced to leave their homes and become refugees to geopolitical power games and offered humanitarian development assistance and aid policies toward Africa and South Asia. Thus, what I call proactive moral realism has begun to emerge as the main motto of Turkish foreign policy in the post-Davutoğlu era. This aims at bringing together (a) hard power and humanitarian norms; (b) selective proactivism and strategic choice; and (c) regaining friends and strategic alliances based on priority setting.

The tenets of a new Turkish foreign policy came to fruition as it simultaneously initiated both its humanitarian policy on the refugee crisis, which meant –unlike the xenophobic European countries’ approach to refugees– unconditional hospitality for almost 3.5 million civilians in its homeland, and its Operation Euphrates Shield against ISIS. The latter also designed to prevent the PKK/PYD/YPG’s attempt to build a cantonal Kurdish state-like entity in northern Syria. On both fronts, Turkey’s moral realism has been successful in its proactive responses and engagements.

Proactive moral realism should be viewed in light of Turkey’s strategic choice to reset its foreign policy in order to adjust to the changing global and regional environment. I have argued in this paper that moral realism has proved to be a correct choice generating outcomes in favor of Turkey’s security, stability, and its national interests. However, for pivotal states and regional powers with middle power capacities to be successful and effective, domestic stability is as important as foreign policy vision. In this sense, I argue that to sustain proactive moral realism, it is imperative to couple it with a much needed democratic reform process at home.17 This will also strengthen Turkey’s fight against the outrageous July 15 coup attempt and terrorism. The stronger Turkey is domestically –through democracy, rule of law, economic dynamism, and living together– the more effective it is in its proactive foreign policy. Herein lies the significance of articulating proactive moral realism outside with democratic reform inside.

Endnotes

- For their valuable contributions to this paper, I would like to thank Megan Gisclon and Cana Tulus.

- For more details, see Bülent Aras and E. Fuat Keyman, Turkey, the Arab Spring and Beyond, (London/New York: Routledge, 2017); E. Fuat Keyman and Şebnem Gümüşcü, Democracy, Identity, and Foreign Policy in Turkey, (Palgrave Macmillian, 2014).

- In writing this paper, I have benefited from in-depth interviews with decision makers and governing elites in Ankara, Berlin, and Brussels in 2015 and since the July 15 coup attempt. The interviews were made within the context of the two projects in which I am involved. Both are organized by İstanbul Policy Center at Sabancı University: (a) “Turkey 2023” (2015-2017) and (b) “Polarization, Consensus and Democracy after July 15th” (2016-2017). Of course, for the arguments and explanations that this paper puts forward, the whole responsibility is my own.

- I have borrowed the term “strategic choice” from Zbigniew Brzezinski, Strategic Vision: America and the Crisis of Global Power, (New York: Basic Books, 2012).

- Bülent Aras, Turkish Foreign Policy after July 15, (İstanbul: İstanbul Policy Center, 2017).

- Zbigniew Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives, (Basic Books: New York, 1997), pp. 124-135.

- For more details, see Ahmet Davutoğlu, Stratejik Derinlik [Strategic Depth], (İstanbul: Küre, 2001), Chapters 2 and 3.

- I have explored the emergence of the Arab Spring and its subsequent crisis in detail in Bülent Aras and E. Fuat Keyman, Turkey, the Arab Spring and Beyond.

- For an adequate account of the negative environment, see Henry Kissinger, World Order, (New York: Penguin Press, 2014).

- Kissinger, World Order.

- For a more detailed account of the failed state, see Zaryab Iqbal and Harvey Starr, State Failure in the Modern World, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2016).

- See David L. Philips, The Kurdish Spring: A New Map of the Middle East, (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2015).

- See endnote 2. I have sorted out these nine parameters, indicating continuities and ruptures between the two periods, by mapping the speeches of decision makers through my in-depth interviews, as well as from the content analysis of articles, columns, and commentaries on Turkish foreign policy since 2015.

- For more details, see John J. Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001). The concept of moral realism resembles Mearsheimer’s concept of aggressive realism. Yet, unlike the latter, Turkish foreign policy’s recent assertive realism places gives attention to humanitarian norms. Moral realism is assertive but not aggressive in that the weight placed on morality gives it specificities.

- Reşat Bayer and E. Fuat Keyman, “Turkey: An Emerging Hub of Globalization and Internationalist; Humanitarian Actor?” Globalizations, No. 9 (2012); I have explored Turkey’s humanitarian state capacity in a comparative perspective in E. Fuat Keyman and Onur Sazak, “Turkey as a Humanitarian State,” POMEAS Policy Paper, No. 2 (July 2014).

- For more details, see E. Fuat Keyman, “Turkish Foreign Policy in the Post-Arab Spring Era: From Proactive to Buffer State,” Third World Quarterly, Vol. 37, No. 12 (2016), pp. 2274-2287.

- For an explanatory analysis of Turkish democracy in recent years, see İlter Turan, Turkey’s Difficult Journey to Democracy, (London: Oxford University Press, 2015).