Introduction

External voting denotes procedures which enable some or all electors of a country who are temporarily or permanently abroad to exercise their voting rights from outside the national territory.1 The term is used interchangeably with absent voting, absentee voting, external enfranchisement, diaspora voting or out-of-country voting. Many countries enable external voting through general provisions in their electoral laws. Additional regulations on its implementation are often administered by legislatures or electoral commissions.2 Postal voting, e-voting, voting by proxy, voting in diplomatic missions or military bases, or other designated places are main options utilized by home states. Countries either choose one of these options or use different combinations of them.3

External voting has emerged as a field of research in the last two decades due to many intertwined factors. First of all, growing cross-border migration has produced populations that are excluded from politics in both their home countries and their countries of residence. Many countries of origin have tried to develop some means to grant them political rights and secure their political participation. More than 115 of the world’s 214 countries have allowed external voting for nationals abroad.4 Recent additions include Ecuador (2008), Egypt (2011) and Libya (2012). In many other countries, that have no system of placing ballot boxes abroad, non-residents are able to vote if they fly to their country of origin such as in Lebanon, India, Zimbabwe, Israel, and Malta. So, granting external voting rights has virtually become a worldwide practice and an international norm. Meanwhile, the interest of migration scholars in transnational political participation has intensified and greatly contributed to knowledge on external voting practices. Existent scholarship provides general explanations for external voting introduction by emphasizing that contextual, country specific factors concerning the history and nature of the relationship between home states and emigrants usually influence its initial introduction and nature of systems.5

Voting at customs and on diplomatic mission grounds remained, and the necessary regulations for this option were brought into force in May 2012 by law before the 2014 Presidential Elections

The arguments supporting external voting are related to the democratic principle of universal suffrage. It is considered that external voting guarantees the political rights of the citizens. It increases political participation given the fact that citizens living abroad are excluded from political life in their host countries and increasingly demand to exercise their right.6 Their participation makes the home country’s political system more inclusive and enhances its legitimacy. Thus, external voting is approached as a critical contribution to democratization.7 Furthermore, it can be viewed as a reflection of government’s political/pragmatic intention to maintain close ties between emigrants and home states.8 As Lafleur notes, external voting is a part of broader diaspora policies in which states develop external citizens mainly to benefit from emigrants as a source of support.9 Some other home state motivations’ include the symbolic acknowledgement of emigrants’ contribution to the home country, the presence of a party which sees political advantage in doing so and emigrants’ campaigning for its introduction.

Arguments against the introduction of external voting are related to territoriality of citizenship rights and difficulties in managing the process, as well as the possibility of low-turnout versus higher cost compared to in-country voting. A traditional republican position conceives polity as something that is drawn by territorial and membership boundaries. Voting rights is an exclusive privilege of citizens who are present in the polity, in other words, requiring residency inside the state territory.10 It is argued that those individuals who bear the consequences of their electoral decisions should be entitled to vote. In the cases of countries who have a huge number of external voters, if they are long term non-residents, their preferences might be decisive and binding for citizens residing inside the state territory. Domestic public may consider such a high political impact over their life as illegitimate. For example, it may be the case that the pattern of political support among external voters differs significantly from that among domestic voters as observed in Yugoslavia in the 1995 election.11 Another counter argument emphasizes that external voting implementations involve many technical and administrative problems. They may challenge the main principles of elections, including the organizing of free and fair elections, the transparency of voting procedures, the freedom and fairness of party competition, and the problem of judicial review of elections held abroad.12 Furthermore, cost per vote is higher outside the country, and it is higher when the population is widely dispersed.13 Another challenge is the assignment of external electors to electoral districts. It is politically very important as it largely decides the extent to which external voters can influence domestic politics.14

As a middle ground, Rainer Bauböck introduces the stake holder citizenship approach. He proposes that external voting should be granted to temporary absentees and conflict-forced migrants, but should be ruled out for generations born abroad because the latter category has no stake in their parents’ countries of origin. In terms of representation, he is in favor of reserved seats for emigrants in parliament because it may diminish the impact of external voting where it could otherwise overwhelm domestic self-government.15

Despite advances in scholarship on external voting, few studies16 so far have tried to explain why emigrants take part in home country elections abroad. It is important to understand, citizens’ motivations and expectations for casting their vote in an election of a country where they no longer reside permanently, given the fact that an extra-territorial location changes the way in which citizens build a relationship with their home state.17 Additionally, host states’ concerns and responses to external voting might be decisive for its implementation. The following study may provide some insight to fill the gap in the literature. As a late comer, Turkey joined the countries that implemented the external voting system in 2014 with its first presidential election. The three interrelated research questions driving this study can be summarized as follows: What are the motivations and the expectations underlying Turkish migrants’ voting abroad? To what extent do emigrants’ perceptions about citizenship, nostalgia, or demand for active involvement in homeland politics play a role in their participation? What do emigrants think about host states’ approach to their voting and the after-effects of voting in their country of residence?

This paper first attempts to shed light on the background to and implementation of external voting, then moves onto analyze the driving forces for emigrants to cast their vote. Host countries’ responses and concerns will be examined by focusing on Germany which hosts nearly 1.5 million Turkey’s electorate. The article will end with some tentative conclusions.

External Voting Experience of Turkey

Turkey has a population of over 75 million, with emigrants constituting around seven to eight percent. A considerable number of these hold Turkish citizenship, making them external voters. According to the 2014 official records, there are 52,692,841 registered voters within Turkey and 2,789,726 registered voters residing abroad, constituting five percent of the total electorate in Turkey.18 Two and half million (85.8 percent) of registered voters abroad reside in eleven Western European countries. There are reportedly around 1.5 million Turkish citizens eligible to vote in Germany, 600,000 in France, 450,000 in the Netherlands, 270,000 in Austria and nearly 200,000 in Belgium.19

The first provision for external voting was placed on the agenda by the Constitutional amendment introduced by the coalition government on July 23, 1995. In principle, this granted Turkish citizens abroad the right to vote at general elections and referendums. However, it required additional provisions in electoral legislation in order to determine applicable measures for voting abroad. In the mid-1990s, public discussions continued about the importance of external voting and possible applicable measures without finalization. The head of the Supreme Board of Election Committee (SBE) proposed voting by mail. Voters residing abroad have been in favor of a mail option due to its lower cost and its practicality, and they made their voices heard through printed media.20 The necessary legal provision determining the applicable measures was not introduced until 2008. Nevertheless, voting at custom gates at airports and border crossing points some time before the election dates were made available to emigrants. The number of people who were able to vote remained limited. The amount of votes cast were only five to seven percent of eligible overseas voters.

In 2008, five new articles on ‘Voting methods and general principles of voters abroad’ were added to the Election Law.21 Voters abroad were allowed to cast votes in general and presidential elections as well as in referendums. The law states that: the SBE consulting with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs decides whether voting at ballot boxes, at customs, by mail, and e-voting would be used according to the conditions of the host country. The Constitutional Court annulled the voting by mail option in the same year after an application by the main opposition party, the Republican People’s Party. It was claimed that voting by mail contradicts the principles of secrecy and independence in elections and is against the Turkish Constitution.

The main prerequisite for citizens to be able to vote was to register on the citizens’ abroad electoral roll either at diplomatic missions or at population registration offices

Online voting has been found to be very complex. Hence voting at customs and on diplomatic mission grounds remained, and the necessary regulations for this option were brought into force in May 2012 by law before the 2014 Presidential Elections with the collaboration of the SBE, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Justice and the Presidency of Turks Abroad and Kin Communities.22

The presidential election was critical due to its being the first election in which the president is elected by the direct votes of citizens instead of being elected by deputies.23 Moreover, it was approached as an initial stage for adopting a presidential system. Candidates for presidency were nominated after securing the support of at least 20 deputies, with each deputy only permitted to support one nominee. Parliamentary parties and parties that jointly received at least ten percent of the votes in the last general elections were able to nominate one presidential candidate. Three candidates were nominated by political parties: Recep Tayyip Erdoğan by the Justice and Development Party (AK Party, Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi), Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu jointly nominated by Republican People’s Party (CHP, Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi) and Nationalist Action Party (MHP, Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi), and Selahattin Demirtaş by the People’s Democracy Party (HDP, Halkın Demokrasi Partisi). The final candidate list was published on July 11, 2014 and due to its late announcement, there was a very tight timetable for external voting which started just 20 days after the publication. One District Electoral Board was established in Ankara to co-ordinate the activities of 1,186 out-of-country Ballot Box Committees.24

The main prerequisite for citizens to be able to vote was to register on the citizens’ abroad electoral roll either at diplomatic missions or at population registration offices by declaring the address of their residence some time before the vote. Only information available after 2012 in Turkish diplomatic missions was able to be used in the preparation of the electoral rolls. Thus, the large majority of overseas voters needed to first check the list from the SBE’s web site in the given time period and then register to be able to vote. The second prerequisite was to make an appointment within a five day period via the SBE web site. When emigrants were not able to do so, they were given an automatic appointment time by the electronic system. There was much confusion in advance both about registration and the appointment system, raising the criticism that many of the procedures were complex and poorly planned.

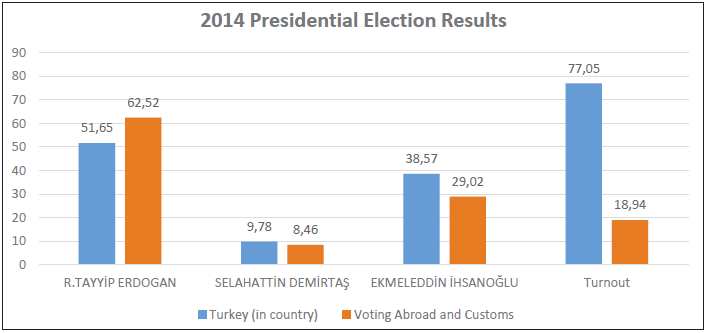

Ballot boxes were placed in 54 countries where more than 500 Turkish citizens reside. Citizens could cast votes there from July 31 to August 4 2014. They were also able to use ballot boxes placed at 42 border crossings from July 26 to August 10. The voting process was thus completed one week before the election held in Turkey. In Germany, 496 ballot boxes were placed at stadiums and fair grounds in seven cities, Berlin, Dusseldorf, Frankfurt, Essen, Hanover, Munich, and Stuttgart. Similarly, Turkish citizens were able to cast votes in six cities in the United States and France, three cities in Australia, Austria, Azerbaijan, two cities in the Netherlands and Belgium, and one city in the United Kingdom. National and local authorities there provided public security personnel. The cost of the election was covered by the Turkish state. Overseas ballots were returned and counted in Ankara and ballots cast at border crossings were counted by their assigned district electoral boards.25 Despite all the bureaucratic and logistical hurdles, a number of citizens abroad did cast their votes. Election results were as following:

In this first implementation, the voter turnout remained very low. Only 8.29 percent of citizens abroad cast their votes outside Turkish national territory and 10.6 of them cast their votes at custom gates (giving a total of 18.9 percent). The actual impact of external votes on the overall results was only 1.3 percent.27 However considering that Erdoğan received 51.79 of total votes, even the slight contribution of external votes helped him to secure his victory. Overall 67 percent of cast votes in European countries went to Erdoğan.

Citizens Abroad and External Vote

The Turkish government was motivated by a number of reasons when introducing the external vote. First of all, it sought to meet the demands of emigrants regarding their political rights, which they had been voicing since the mid-1970s. According to Euro-Turks-Barometer 2013, prepared by Hacettepe University28, citizens abroad are interested in casting votes for Turkey’s elections and 74 percent of them noted that they would go to the ballot box if they were given external voting rights. Secondly, Turkey tried to include citizens abroad in the polity through granting them political rights, thus, to consolidate democracy by embracing a more inclusive citizenship approach. Thirdly, the government party had expected to gain votes for its candidate in the critical election in which a simple majority was necessary to be elected as the President. Political analysts and scholars expected that Erdoğan might enjoy relatively stronger support from voters abroad, even receiving around 50 to 65 percent of all votes.29 Strengthening this expectation was the fact that, in the 2011 general elections, the AK Party had received 59 percent of the votes cast at customs gates.

Turkey tried to include citizens abroad in the polity through granting them political rights, thus, to consolidate democracy by embracing a more inclusive citizenship approach

As studies demonstrated, the larger parties, and particularly the party in power, have a clear advantage in mobilizing their supporters abroad.30 Turkish political parties, through sister associations abroad, mainly imitated campaign strategies used in Turkey including the organization of rallies for party leaders, door-to-door campaigning, and distribution of brochures. They informed citizens about the election procedures, directed respective deputies who came to meet the constituency, organized activities to get voting appointments and even in some cases organized transportation to bring people to voting stations.31 Civil society organizations established by emigrants in Western European countries affiliated with the government party like Avrupalı Türk Demokratlar Derneği(UETD), presented the election as ‘an opportunity to have a better common future with Turkey,’ while those affiliated with opposition parties presented the election as a last opportunity to ‘save Turkey from entering an undemocratic path.’ However, it was not clear why voting was important for citizens abroad given the fact that nothing concrete could be promised to them. Considering the more symbolic value of the presidency in the Turkish political system, the possible winner could not offer emigrants any political gain. For instance, the AK Party proposed a new vision for Turkey 2023 as a democratic, prosperous and leading country and mentioned the importance of citizens abroad in achieving this ideal. But, there is not a single sentence about citizens abroad in Erdoğan’s 81-page 2014 Presidential Election Vision Document. Furthermore, there was no clear timetable to introduce reserved seats for external voters that might make external voting more meaningful. So, it is puzzling that emigrants wanted to vote in an election of the home country where they no longer reside. Many of them do not have the intention to return therefore what do they expect to gain out of voting?

Methodology

This study utilizes qualitative research methodology. The main data was drawn from the field work in Germany, selected because almost half of the eligible Turkish voters abroad reside there.32 The data was collected from three complementary sources to understand the voters’ expectations, motivations, and concerns about participating in the homeland elections in their host country. First, participatory observations and interviews33 were administered during the actual voting process in Dusseldorf, the most crowded election district abroad in the 2014 Presidential Election. A total of 10 semi-structured interviews were conducted with ballot box observers of parties and voters between 31 July and 4 August 2014, the period when Turkish citizens in Germany were able to cast votes. Interviewees were asked the following questions: Did you ever cast a vote before and if so where?; What is the importance of voting abroad?; What do you expect from voting and from the Turkish state?; How can voting contribute to your life in Germany and your ties with the homeland? The number of questions remained limited and responses were not recorded due to the chaotic environments surrounding the electoral stations. Instead, notes were taken and transcribed as soon as possible. The second data source is semi-structured in-depth interviews with the stake-holders and actors involved in the voting process abroad. The stakeholders are those individuals, groups and organizations that have an interest or ‘stake’ in voting. Primary stakeholders are representatives of the electoral management body (in this case staff of embassies and consulates), representatives of Turkish political parties (activists from party affiliated associations), election monitors (non-partisan observers), electorate (individuals, representatives of civic associations, and politicians representing emigrants in Germany) and the media (journalists). Keeping these stakeholders in mind, fifteen interviews were conducted before and after the election days over a month, in different cities of Germany including Cologne, Dusseldorf, Duisburg and Frankfurt. The sample included two serving consulate generals (of Dusseldorf and Cologne), one civil servant, two Turkish politicians serving in German parties, four party activists, two journalists, representatives from two emigrant NGOs, one academician and one migration expert. They were asked the same questions stated above and additional questions regarding the concerns of German authorities and public. This set of interviews was audiotaped. All interviewees have an emigrant background from Turkey; hence interviews were conducted in Turkish. No overt question had been devised, concerning the interviewees’ voting choices. The third data source is composed of press reports, political party papers, election related documents publicized by emigrant associations, newspapers published in Germany and Turkey between May 20 and August 20, 2014, both in Turkish and German; web sites, online civil society forums related to elections, and TV programs targeting citizens abroad. All interviews were transcribed and text analyzed using content analysis to identify and describe themes which closely connected to the research question of why citizens abroad vote for the homeland election and what are their concerns with regards to their country of residence. Content analysis was adopted by identifying specific themes such as citizenship, belonging, homesickness, Turkishness, benefits, representation rights, German sensibilities, German concerns, etc. as categories. The texts –interview transcripts, news, media accounts, and articles of columnists- were coded according to these categories. Results were interpreted with the objective of answering research questions and entering into dialogue with the findings of existing studies.

Two factors that drive emigrants to vote are the symbolic dimension of citizenship rights as well as the desire to have a voice in Turkish politics that can be identified as electoral political participation

In technical terms, the sample from field work in Germany is a convenient, exploratory rather than an explicative one. It cannot be assumed to be fully representative of all hosting countries and emigrant voters,34 but it is useful to provide important insights given the fact that little data is readily available on the political behavior of emigrants from Turkey and the position of hosting countries. Participatory observation and interviews could not build on any random sampling criteria, as it only involved subjects who were interested in voting abroad rather than all emigrants. This same objection is also valid for the most empirical research on migrants’ political participation.

Understanding of External Voters’ Motivations and Expectations

Political science literature on electoral behavior analyzes driving forces dictating one’s vote and political choices. While the first fundamental question of the literature is why some citizens vote while others do not, the other main question is why citizens cast their vote for a certain party or a candidate, in other words what are the factors influencing voters’ electoral preferences. Hundreds of articles, chapters, and books have been published to answer various versions of these questions, testing existing hypotheses and developing novel models/theories. Although, it is obviously beyond the scope of this article to provide a comprehensive review of the literature on political behavior, some basic findings will be briefly addressed below in so far as they concern the main focus of this article, the external voting.

The well-known simple equation explaining individual’s voting turnout behavior presumes it is a function of voter’s motivation to vote, his or her ability to vote, and the difficulty of the act of voting.35 In this equation, motivation refers to desire and intention to vote. It can come from various sources including: voter’s strong preference for one candidate/party over other competitor(s), voter’s belief that voting is a responsibility and/or obligation and pressure from voter’s family, friends, social groups and associations. The ability to vote is related to having legal eligibility, capacity, and information required to cast a ballot. Difficulty refers to aspects of external conditions such registration procedures, distance of polling stations and availability of information about candidates. Further studies have advanced this equation by elaborating existing factors and proving the importance of others. Joshua Harder and Jon A. Krosnick review these factors by grouping, including demographic factors (education, income, occupation, age, gender, mobility, residency, race), social and psychological factors (neighborhood characteristics, marriage, participation in civic organizations, trust, group solidarity, sense of political efficacy, civic duty, habit, patience, genetic), characteristics of a particular election (strength of a candidate preference, similarity in terms of policy preferences, negative advertisement, closeness in race, campaigning) and the cost of registering a vote.36 These factors may also play a role in external voting but, to the best knowledge of the author, there has not yet been an academic publication on the topic. For instance two important recent studies, of Boccagni, and Boccagni and Ramirez, question the motivation and expectations underlying emigrants’ electoral participation of Ecuadorians abroad without explicitly consulting with the electoral behavior literature, rather these studies remained in the terrain of migrant transnationalism literature. Boccagni’s study on electoral participation of Ecuadorians in Italy in the 2006 presidential elections suggests that emigrants’ involvement was mainly driven by the patriotic-homesick drives, rather than strictly political expectations.37 In a more comprehensive study using the survey data on Ecuadorean voters, from nine cities in seven countries during the 2008 constitutional referendum, it is found that “electoral participation from abroad displays, even within the minority of real voters, a deeply ambivalent attitude towards the homeland, whereby nostalgia and patriotic identification go hand in hand with suspicion and disenchantment about Ecuadorean politics and the future prospects of the country.”38

The exploration of Turkey’s first external voting experience reflects both symbolic and active dimensions of citizenship

An examination of voting preferences has been the second main focus of electoral studies. These studies mainly emphasize three sets of factors: social factors such as socio-economic and demographic characteristics; psychological factors such as party identification; rational choice such as utility maximization inspired by economists. However, the models constructed within electoral studies have failed to examine external voters’ political behaviors mainly because of two reasons. Firstly, external voting rights are a relatively recent phenomenon and secondly, classical electoral studies have primarily used surveys conducted with voters residing within the borders of a certain country, not with voters residing outside of the country.

Nevertheless, migration studies, particularly the scholarship on political mobilization of immigrants and ethnic minorities, have been interested in understanding the political choices of migrants particularly in host countries. Within this literature, recently, the research strand on immigrant political transnationalism has emphasized the political participation of emigrants in home country elections. To the best knowledge of the author, these two bodies of literature, electoral studies and migration studies have rarely been combined except for a few studies such as the study of Lafleur and Sanchez-Dominquez on Bolivia’s external voting in the 2009 presidential election.39 Lafleur and Sanchez-Dominquez address the question of what variables influence the electoral behavior of citizens voting in home country elections by consulting with classical theories of electoral studies and migration literature and by utilizing the survey data collected from Bolivian external voters who participated in the polling stations abroad.40 Scholars reached four conclusions about political choices of emigrants. First, “external voters are likely to continue to have voting behavior similar to that of non-emigrants with the same background after they migrate.” Second, “voters abroad were not necessarily aware of the position of political parties on the left-right political continuum or did not find it to be a relevant scale to assess.”41 Third, as most external voters seem poorly informed about the election, they are not able to act as interest-driven voters. Lastly, “involvement in ethnicity-based associations has been demonstrated to have an effect on emigrants’ involvement in host and home country politics.”42 Although these findings are insightful, the lack of survey data impedes the testing of similar hypotheses in the case of Turkey’s first external voting experiences.

Similar to different case studies emphasizing external voting, the findings of the research on Turkey’s external voting experience in Germany shows that there are diverse factors driving emigrants who register as voters from abroad to make use of their external voting rights. Two factors that drive emigrants to vote are the symbolic dimension of citizenship rights as well as the desire to have a voice in Turkish politics that can be identified as electoral political participation.

The idea of symbolic relevance of external voting has not been addressed within the literature on political behavior because this literature has not been interested in understanding the motivations and expectations of external voters in going to the ballot box and/or casting votes for a certain party as explained above. Thus, there is a need to conceptualize the emigrants’ political behavior, mainly drawing from the migration studies literature. The concept of ‘symbolic meaning of citizenship’ is used by Dorothy Schneider and Sune Laegaard to indicate different citizenship status of immigrants and diversifications in the perception of themselves as well as those of host states.43 It states that “citizenship means something different for native born and naturalized citizens.” Drawing on theoretical understanding of external voting,44 this phrase can be adopted for emigrants in a way that citizenship may mean something different for citizens residing abroad and those living in national territories, regarding their political ties with the homeland.45 For citizens abroad, as Boccagni and Ramirez point out there is a widespread perception among emigrants that the external vote is a fundamental citizenship right, whatever the electoral stake.46 Emigrants may feel a personal sense of civic duty by believing that they have a moral obligation to participate in politics, at least to vote in an election. Even if voting is not compulsory, some emigrants prefer to cast a vote due to their conviction about the relevance of the vote for citizenship as well as the perception of voting as a social norm. These can motivate citizens abroad to go to the polls although voting may not bring any tangible benefits to them. More specifically, even though citizens abroad have economic, political, or social ties with the home state, they are not proper subjects regarding individual rights and governmental obligations. The President and/or government of the home country, put in place by an electoral system, would not show equal concern for citizens living inside its own jurisdiction and those living within another sovereign territory, thus the latter do not have equal status with the former.47 Hence, exercising the right of citizenship by going to the ballot box has different meanings for emigrants –mainly symbolic– nevertheless it is still important and valuable.

The concept of political participation implies the active dimension of citizenship; however, no definition is universally accepted.48 It simply refers to a range of activities that “has the intent or effect of influencing different levels of a political system and/or government action”49 The range of activities takes two main forms. First is direct electoral participation (in other words conventional form), such as voting or running for election. Second is the non-electoral participation (less conventional forms), such as joining protests, demonstrations, sit-ins, hunger strikes, boycotts, signing a petition, membership in association etc. Emigrants tend to involve in the politics of their origin country by using some of these forms jointly in accordance with the host country and emigrant community characteristics. Voting abroad is rightly categorized as a way of electoral participation.

The exploration of Turkey’s first external voting experience reflects both symbolic and active dimensions of citizenship. These dimensions, as discussed below, were raised by voters when they were asked about their motivations and expectations. The comments of voters, whom the author had a chance to talk to at the polling station in Dusseldorf, on 30 June 2014, point out the symbolic dimension of citizenship. An old woman stated that “we feel we are citizens, thanks to God.” Another woman added: “I came here in 1972, I have never voted, never in customs, this is my first voting experience.”

One German Greens deputy who is a Turkish emigrant and naturalized as a German citizen summarizes the meaning of voting by pointing out the crux of the issue in the following terms: “The right of electing and being elected is a fundamental right. It is a problem that has not been given to us until today.”50

One commentator noted:

Even if the impact of our voting is minimal, I want to exercise my voting right. The Turkish state gets our money through passport fees and compulsory military service fees. These kinds of fees return back to citizens within Turkey because they benefit from state services. What about us? The Turkish state has to provide some services to us. Casting a vote is important for me because of that. At least, we are not treated as outsiders after 40 years.51

It was emphasized by a columnist how voting is a democratic citizenship right: “In a globalized world which has become a big village, people are able to influence developments in faraway places. It is a serious defect and injustice for citizens abroad to be excluded from political processes in their motherland... it is a democratic right.”52

According to one politician, voting is a way of being a real citizen, being involved in politics, and a way to raise their demands. He noted that: “First of all we felt ourselves to be first class citizens. We had this right theoretically, but not practically… When problems are fixed, we will be active in Turkish politics. We will raise our problems effectively and assertively via our deputies, bringing positive results. Voting is a beginning.”53

One diplomat interviewed added that

People have been not able to exercise their fundamental political right neither in Turkey nor in Germany for almost 52 years. They have some demands and they want to participate in governance. The main road of participation is casting their votes, thus they can voice their demands, because they have become a very important asset for politicians.54

Some experts interviewed had high expectations for the benefits of voting, adding that:

Citizens here became very important for politicians. In the past politicians came here, listened to emigrants, they said ‘what a pity’, then they left without taking any action. But, right now, they will not be able to be elected without the approval of emigrants. Thus, emigrants assertively will able to voice their demands and expectations. In a short time, we will see its direct benefits like the decreasing of passport fees.55

An exceptional way of mobilizing the expatriate vote and emphasizing its importance is to set aside parliamentary seats for expatriates according to their density, as being applied in France, Italy, Portugal, Colombia, and Tunisia.56 There has been increasing demand and expectation for creating extraterritorial districts and to have separate representatives for emigrants in the Turkish parliament. Those interviewed saw representation as the natural consequence of having voting rights.

External voting management requires home states to negotiate with host states in order to decide many critical issues to administer elections abroad

One diplomat said that “the most important expectation is the granting of the right to represent in the next election.”57 The president of the UETD, Süleyman Çelik, pointed out that “if the participation was higher, it would be easier to get representation rights later, otherwise the doors will be shut down.”58 Similarly, one expert answered the question about why immigrants, particularly third generation, are interested in the Turkish election as follows: “I personally know many people who want to become candidates, if parties target the electorate here; they need to choose candidates here as they know the constituency better than those appointed from Turkey.”59

Although many emigrants believe in the importance of external voting and approach it as a democratic right, there are serious concerns about the influence of possible election campaigns in host countries and their relationship with the host country. Those in Germany particularly voiced their concerns. Many experts and politicians interviewed also shared the fear that voting in Turkey’s elections may negatively influence the political integration of immigrants. They state that Turks in Germany in general are apolitical and many of those who are politically active are interested in Turkish, rather than host country politics.60 Moreover, interviewees compared and contrasted the two countries’ political cultures, and shared the observation that Turkish politics is very sensational and polarizing, while German politics is more stable and less polarizing. One journalist clarifies how external voting may influence the integration issue, by criticizing Turks in Germany. He says that: “Germans do not oppose immigrants there getting interested in Turkish politics, but the degree is important. Often emigrants do not try to contribute to the solution of problems in Germany…We will neglect our real problems here if we behave like this, if we bring Turkey’s problems and conflicts here. This will harm our common future here.”61

Almost all interviewees shared their concerns about the risk of socio-political polarization and bringing problems into the host country. This concern is fed by the fact that historically tensions among various political/ideological factions in Turkey (Sunnis versus Alevis; Turkish nationalist versus Kurdish nationalist; secular versus conservative; pro-Erdoğan versus anti-Erdoğan), have been directly reflected among the immigrant communities from Turkey.

Hosting States’ Concerns about External Voting

External voting management requires home states to negotiate with host states in order to decide many critical issues to administer elections abroad. Generally, respective diplomatic missions and foreign ministries from the countries of origin carry out these tasks and become responsible for the coordination of external voting programs. The home state’s role is confined to being facilitator rather than that of organizer. However, there are no consistent policies, practices or standards to guide host states in this realm. They may refuse the requests due to reasons ranging from the lack of legal base to concerns about sovereignty, security and politics.62 For example, until 1989 Switzerland refused to allow foreigners to vote in foreign elections on its soil or some European countries refused Bosnians’ demands to cast their vote in the 1996 Bosnia and Herzegovina election. Host states may be more eager to allow elections if there is an international advocacy and pressure, support for an identified political cause of the eligible electors they host, or sympathy for a particular religious or ethnic group.63 Even in the case of acceptation, they tend to carry very limited responsibilities and ask home countries to take serious security measures.

Countries hosting migrants from Turkey are not exceptional in terms of their unwillingness to allow a foreign country’s political activities on their soil. The main host countries, Germany, Austria, and the Netherlands, had concerns about public security. They could not directly reject the demand for external voting because of European Union norms. Germany is the most concerned as it hosts the most populous migrant Turkish population.64 In fact, the fear of its sovereignty being violated is not voiced by German authorities rather it is concerned about public security during the actual voting process. Considering the form of voting, namely by person-vote, Turkish embassy and consulate grounds were not adequately spacious to place ballot boxes. Some other public facilities like fair grounds, sport stadiums and similar premises had to be reserved as polling sites making public security an issue. Furthermore, the past experience of German authorities dealing with political activities and clashes of different ideological/political immigrant groups from Turkey, specifically Turkish versus Kurdish nationalists groups due to conflict in the homeland, necessitated extra security measures to be taken by German public authorities. Prior to the prospective voting, the Turkish authorities were asked to take additional security measures. As a compromise and to assure Germany, the Turkish authorities chose to limit the number of polling stations to seven and introduce both online registration and an appointment system. A certain level of standardization in these procedures was provided in all hosting countries. Thus, election authorities on the whole diverged from the administrative activities within Turkey, where there is no appointment system and polling stations are very accessible. These measures made the actual process very difficult for those who are not used to the internet and reside far from polling stations. According to the author’s observation and conducted interviews, these are the main reasons that led to a low turn-out.65

In the 2015 Parliamentary election on June 7, citizens abroad were able to cast votes over a longer period and the number of polling stations was increased

Another reason for Germany’s uneasiness stems from the fact that foreign electoral campaigns in host countries raised questions about the loyalty of immigrants. One ambassador explained the problem clearly: “There is a competition between Turkey and Germany in receiving the attention of Turks here. Germany wants Turkish immigrants to be interested in German politics here, while Turkey wants to sustain ties with emigrants. In fact, voting will increase Turks’ sensibilities about Turkish politics.”66

In common with many other host countries, Germany dislikes the relocation of Turkish homeland politics in its soil. German authorities believe that Turkish immigrants and politicians bring Turkey’s problems into Germany. In general, experts, diplomats and NGO representatives emphasize the importance of voting while giving reminders of Germany’s sensibilities and apprehensions. They did not want to agitate the German authorities and public. For example, after the visit of former Prime Minister, current President Tayyip Erdoğan to Cologne, the North Rhine-Westphalian (NRW) Minister for Integration Guntram Schneider said that “it is not acceptable that Erdoğan repeats the role of the President in NRW, Prime Minister of the Turks in NRW is Hannelore Force and not Mr. Erdoğan… NRW is the wrong place for Erdoğan’s campaigning.”67 Meanwhile, the German federal government warned Erdoğan to speak cautiously and stated its expectation for a “responsible and sensitive event.”68

One of the Turkish interviewees, who is the general secretary of a civic association established by conservative Turks in Essen Duisburg, stated that “Erdoğan was considered to be involving himself in German domestic politics, by addressing Turkish immigrants and their problems there.”69 Compounded with Erdoğan’s bitter criticism of Germany in many occasions, such rallies aggravated existing concerns. German politicians and journalists made comments about how these kinds of massive manifestations proved that the election atmosphere in Turkey was carried to Germany.70 It has been stated that “the Turkish elections abroad would harm the German public’s attitude to Turks. Germans started to question why Turks transfer their absurd and unethical conflicts to our country.”71 Similarly, Öztürk writes in his column that “A negative political language used by Turks may enhance the thesis of populist groups about the impossibility of living together in Germany. Also, it may lead to some political tensions. If tensions appear in the streets, it will not be easy to explain it to others in Germany.”72

These perceptions are not independent from bilateral relationships between Germany and Turkey. Tense relationship between the two countries, starting two years prior to the election period, is observable although relations had been in a good shape in the first ten years of the AK Party rule. The German media’s growing anti-Erdoğan stance related to his perceived “authoritarian tendencies” worsened with some violent reactions to the Gezi protests that turned into nation-wide anti-government demonstrations. In particular, the high level popularity of former Prime Minister Erdoğan among Turks living in the country led to questions about the integration and allegiance of immigrants. Erdoğan is a very popular politician for many emigrants originating from Turkey, particularly for Islamists and conservative Turks in European countries. The popularity of Erdoğan among immigrants manifested in crowded rallies attended by more than twenty thousand Turkish immigrants in European cities, such as Cologne, in May 2008 and in 2014. Conversely there were also massive anti-Erdoğan protests. German media and politicians seem to believe that the interest in homeland politics is common among German Turks, even those who no longer hold Turkish nationality, although the interest in German politics for these same people is limited. It is reported that “the reception for guests to Turkish politics in Cologne is more emotional than all the combined German party political rallies of previous years.”73 When, in 2008, posters referring to Erdoğan as “our prime minister” were hung everywhere, and he made a speech giving some controversial messages about integration, the German public/media criticized him for harming the integration of Turkish immigrants. Such a situation make Germans question the immigrants’ allegiance and belonging to the community of the host country.

The Turkish state has tried to invest more in both emigrants and co-ethnic communities abroad

Erdoğan’s visit to Cologne in May 2014 intensified discussions although formally Erdoğan came to give a speech for the 10th anniversary of a Turkish NGO, European Democratic Union (UETD) that is seen to be strongly affiliated with the AK Party. The mayor of Cologne Jürgen Roters advised the Prime Minister to cancel the visit. Then, the German newspaper Bild, in its online version published an open letter with the headline of “You Are Not Welcome and You Are Not Wanted Here” in both German and Turkish by criticizing Erdoğan for his authoritarian policies and involvement in alleged high-level corruption in Turkey.74

Due to all the aforementioned reasons including the risk of polarization, Germany’s uneasiness and different political cultures, there are some immigrant NGOs and journalists who, even though they agree that voting is a democratic right, feel that emancipation from Turkish politics and its agenda is vital.75

A Note about the External Votes at the 7 June Election and the 1 November Snap Election

In the 2015 Parliamentary election on June 7, citizens abroad were able to cast votes over a longer period and the number of polling stations was increased.76 For example, ballot boxes remained open for 23 days at 13 polling stations in Germany,77 unlike the more restrictive implementation in 2014 when 7 polling stations had been available for only four days. Moreover, it was realized that the online appointment system had led to serious hurdles in the previous election; therefore this procedure was totally eliminated. All of the new arrangements in the 2015 election facilitated the emigrant’s electoral political participation. Accordingly, turnout rate increased from 8.2 to 32.5 percent. A total of 918.302 citizens abroad cast votes at the polling stations worldwide, while 482.743 votes were cast in Germany alone.78 While the AK Party took 50.4 percent of votes, HDP stood as the second party with the 20.4 percent. Accordingly, addition of the external votes changed the number of deputies shared by parties in some provinces. While these votes brought two deputies to the AK Party in Izmir and Amasya respectively, it shifted one deputy from the MHP to the HDP in Kocaeli.

Turkish expatriates went to the ballot box for the snap parliamentary election of November between 8 and 25 October.79 This time, as the political parties realized the importance of external votes, they intensified their campaigns abroad. All major parties organized rallies and visits to Western European cities. Moreover, the AK Party prepared an Election Manifesto for Citizens Abroad, while both AK Party and HDP provided transportation facilities to their potential constituents in Germany.80 It seems that parties with a strong organizational structure and affiliated networks of associations abroad were able to reach more external voters on the eve of elections.

In terms of results, the turnout rate of the external votes at the 1 November snap election increased from 32.5 to 45 percent with 1.285.108 valid votes.81 The distribution of votes by each party varied across host countries. According to non-official results82 the AK Party increased its external votes from 50.4 percent to 56.2 percent which makes it the only party that was able to increase their votes abroad. Overall, the AK Party secured five seats, with external votes which were over 50 percent of cast votes in Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, France and Austria –countries where more than 75 percent of external voters reside. Not surprisingly and in accordance with domestic votes, there was not much difference in the percentage of votes received by the main opposition, the CHP. A slight decrease of 0.4 percent was observed by CHP (from 16.3 percent to 15.9 percent) whereas there was bigger change in the pro-Kurdish HDP and the MHP’s votes (7.1 percent). The HDP gloried in the previous parliamentarian elections as the second party abroad and despite a slight decrease from 21.4 percent to 18.1 percent in November, this position was maintained. In fact in the second election it is considered that external votes helped the HDP critically pass the threshold (of 10 percent) with 10.8 percent of total votes cast. In this context, survey studies examining the electoral behavior of Turkish citizens abroad may shed light on the similarities and differences not only between the voting preferences of external and domestic voters but also of between external voters across countries.

In terms of the argument presented in this article regarding the concerns of host countries, the November snap election provides important insights that necessitate further scholarly research. For example, the letters sent by the AK Party to the voters in Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium sparked a diplomatic crisis between authorities of Netherlands and Turkey. It is even reported that the Netherlands plan to put the issue on the agenda of the Organization of Security and Cooperation in Europe on the basis of electoral independence.83 Furthermore, the leaders of extreme right parties in the host countries, such as Geert Wilders, of Partij van de Vrijheid in the Netherlands, used the Turkish voters’ voting preferences towards the AK Party to marginalize them and further his anti-immigrant discourse.84 Therefore, it can be presumed that external voting may receive substantial attention in the host countries and may spark some discussions on migrant integration.

Conclusion

In the last decade Turkey has sought to maintain her ties with the Turkish community abroad by introducing many rights and institutions in a context for which remittances have not been so far been critically important to the Turkish economy. The Turkish state has tried to invest more in both emigrants and co-ethnic communities abroad. External voting is one of the latest initiatives to target those who have left Turkey, but have retained Turkish citizenship. It is of the utmost importance as a considerable number of them (two and half million) do not hold political rights in the hosting countries due to their own preferences, conditions or the lack of dual citizenship rights, as in Germany.

The growing literature on external voting has rarely addressed the motivations of emigrants to vote in homeland elections and the concerns of hosting countries. The analysis developed in this article displays two main motivations and expectations of emigrants, namely the symbolic meaning of exercising a citizenship right and desire for electoral participation in Turkish politics. First of all, emigrants preferred to cast their vote with the motivation of exercising a citizenship right that was not available to them for a long time both in their home and host country. They have a conviction that voting is a fundamental citizenship right although results would not bring them material or specific benefits; this was defined in this article as a symbolic dimension of citizenship. It could be claimed that the motivation of civic duty matters, because voting for the Turkish election made emigrants feel like citizens and demonstrated belonging as well as loyalty to the political sphere of Turkey against the fact that voting is not an obligatory civic responsibility for them (non-voters could not be sanctioned). The second finding is that voting provided them with an opportunity for political participation as well as to reveal their potential connectedness to domestic political life and its political institutions although they do not reside within the borders of the country anymore. Some external voters seem to perceive voting as a tool for involvement in Turkey’s politics rather than considering it as simply a citizen’s right. These results partially differ from the findings of the few studies that questioned why citizens abroad go to the ballot box. In the case of Turkish emigrants’ initial experience, the homesickness theme was not recalled by emigrants. Although political expectations are not very rigid they are still a more relevant source of motivation. Moreover, concerns of Germany about the Turkish election resemble other host countries, such as Canada that perceives external elections of France on its soil as a foreign interference.85

To conclude, Turkey’s experience with voting abroad continues to improve, as observed in worldwide examples, even given the fact that designing and implementing a mechanism for external voting carries many dilemmas and a level of complexity, this form of political participation may transform home and host country politics. The issue of external voting will receive further attention not only from stake-holders such as political parties, migrant associations, electoral bodies but also from scholars of political science, comparative politics and migration studies in the near future.

Endnotes

- Nadja Braun and Maria Gratschew, Voting from Abroad: The International IDEA Handbook, (Stockholm: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance; Mexico City: Federal Electoral Institute of Mexico, 2007), p. 8.

- Dieter Nohlen and Florian Grotz, “The Legal Framework and an Overview of Electoral Legislation,” in Voting from Abroad: the International IDEA Handbook, (Stockholm: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance; Mexico City: Federal Electoral Institute of Mexico), p. 68.

- For more information see “The History and Politics of Diaspora Voting,” (December 16, 2014), retrieved from https://www.

overseasvotefoundation.org/ files/The_History_and_ Politics_of_Diaspora_Voting. pdf. - See Braun and Gratschew, Voting from Abroad: The International IDEA Handbook, p. 3.

- For recent studies about external voting see Michael Collyer, “A Geography of Extra-territorial Citizenship: Explanations of External Voting,” Migration Studies, Vol. 2, No. 1 (March, 2014), pp. 55-72; Robert Smith, “Contradictions of Diasporic Institutionalization in Mexican Politics: The 2006 Migrant Vote and Other Forms of Inclusion and Control,” Ethnic and Racial Studies, Vol. 31, No. 4 (2008), pp. 708-741; Michele Lafleur, “Why Do States Enfranchise Citizens Abroad? Comparative Insights from Mexico, Italy and Belgium,” Global Networks, Vol. 11, No. 4 (2014), pp. 481-501; Alexandra Delano, “The Diffusion of Diaspora Engagement Policies: A Latin American Agenda,” Political Geography, Vol. 41 (2014), pp. 90-100; Laurie Brand, “Arab Uprisings and the Changing Frontiers of Transnational Citizenship: Voting from Abroad in Political Transitions,” Political Geography, (2013), retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/

science/article/pii/ S0962629813001169, pp. 1-10. - Henry Rojas, “A Comparative Study of the Overseas Voting Laws and Systems of Selected Countries,” Development Associates of Occasional Paper, No. 17 (2004), retrieved November 17, 2014 from http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/

PNADA596.pdf. - “Voting from Abroad,” Aceproject, (December 08, 2014), retrieved from https://aceproject.org/ace-en/

topics/va/host-country-issues/ host-country-issues. - Brett Lacy, “Host Country Issues,” in Voting from Abroad: the International IDEA Handbook, (Stockholm: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance; Mexico City: Federal Electoral Institute of Mexico), p. 131.

- Jean-Michel Lafleur, “The Enfranchisement of Citizens Abroad in a Comparative Perspective,” Paper presented at the Conference Political Rights in the Age of Globalization, University of St. Gallen, 19 September 2013.

- Rainer Bauböck, “Expansive Citizenship: Voting Beyond Territory and Membership,” Political Science and Politics, Vol. 38, No. 4 (January 2005), pp. 683-687.

- See Nohlen and Florian Grotz, “The Legal Framework and an Overview of Electoral Legislation,” p. 72.

- Nohlen and Grotz, “The Legal Framework and an Overview of Electoral Legislation,” p. 67.

- Jeremy Grace, “Challenging the Norms and Standards of Election Administration: External and Absentee Voting,” IFES, (2007), retrieved November 17, 2014 from http://www.ifes.org/~/media/

Files/Publications/White% 20PaperReport/2007/593/IFES% 20Challenging%20Election% 20Norms%20and%20Standards% 20WP.pdf, pp. 35-58. - See Nohlen and Grotz, “The Legal Framework and an Overview of Electoral Legislation,” p. 69.

- Rainer Baubock, “Stakeholder Citizenship and Transnational Political Participation: A Normative Evaluation of External Voting,” Fordham Law Review, Vol. 75, No. 5 (2007), p. 2394.

- As an exception see Jean-Michel Lafleur and Maria Sanchez-Dominquez, “The Political Choices of Emigrants Voting in Home Country Elections: A Socio-Political Analysis of The Electoral Behavior of Bolivian External Voters,” Migration Studies (2014), pp.1-27; Paolo Boccagni and Jacques Ramirez, “Building Democracy or Reproducing ‘Ecuadoreanness’? A Transnational Exploration of Ecuadorean Migrants’ External Voting,” Journal of Latin American Studies, Vol. 45, No. 4, (2013), pp. 721-750; Paola Boccagni, “Reminiscences, Patriotism, Participation: Approaching External Voting in Ecuadorian Immigration to Italy,” International Migration, Vol. 49, No. 3 (2011), pp. 89-98.

- See Collyer, “A Geography of Extra-territorial Citizenship: Explanations of External Voting,” p. 68.

- See the official website for further details: http://www.ysk.gov.tr/ysk/

content/conn/YSKUCM/path/

Contribution%20Folders/HaberDosya/2014CB-Kesin- GumrukYurdisi-Grafik.pdf?_ afrLoop=

22656611625189210. - For more info see: http://www.todayszaman.com/

news-350260-pm-as-candidate- for-president-may-receive- half-of-overseas-vote.html. - Ali Kılıçaslan, “Sözünde Durmayanlar, Utansınlar,” [Shame on Those Who Did Not Meet Their Promise] and ‘Yine Seçim Hakkı’ [Again, the Right of Voting], (1997).

- See Law Number 5749, Article 10, Seçimlerin Temel Hükümleri ve Seçmen Kütükleri Hakkında Kanunda Değişiklik Yapılmasına Dair Kanun [Law Regarding a Change in the Fundamental Principles of Elections and Ballot Boxes] and Law 298, Article 94/A Seçimlerin Temel Hükümleri ve Seçmen Kütükleri Hakkında Kanun [The Fundamental Principles of Elections and Ballot Boxes], (13 March 2008).

- See: http://www.ytb.gov.tr/index.

php/yurtdisinda-oy-kullanma. html. The official link to the law: http://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/ eskiler/2012/05/20120518-3.. htm. - See the constitutional amendment of 2007 (Amendment 21/10/2007-5678/2) stipulated popular elections for the office of the president, the first to be held in 2014.

- OSCE/ODIHR Report, “OSCE/ODIHR Limited Election Observation Mission Final Report,” (21 August 2014) retrieved from http://www.osce.org/odihr/

elections/turkey/126851? download=true. - See OSCE/ODIHR Report, 2014

- See the related info on http://www.ysk.gov.tr/ysk/

faces/HaberDetay?training_id= YSKPWCN1_

4444005790&_afrLoop=457755354627734&_ afrWindowMode=0&_afrWindowId= dpkm594z3_

1#%40%3F_afrWindowId%3Ddpkm594z3_1%26_afrLoop% 3D457755354627734%26training_ id%3DYSKPWCN1_4444005790%26_ afrWindowMode%3D0%26_adf.ctrl- state%3Ddpkm594z3_35. - See the official website for further details: http://www.ysk.gov.tr/ysk/

content/conn/YSKUCM/path/ Contribution%20Folders/ HaberDosya/2014CB-Kesin- GumrukYurdisi-Grafik.pdf?_ afrLoop=22656611625189210. - Murat Erdoğan (ed.), “Euro-Turks Barometer,” Hacettepe Migration and Politics Research Center, (2013), retrieved December 14, 2014 from http://www.hugo.hacettepe.edu.

tr/ETB_rapor.pdf. - “PM as Candidate for President Pay Receive Half of Overseas Vote”, Todays Zaman, 11 September 2014.

- IDEA, 2007, p. 106.

- Yunus Ülger and Tuncay Yıldırım, “Hafta Sonu Bereketi,” Sabah Online, retrieved August 02, 2014 from http://sabah.de/haftasonu-

bereketi/. - Almost 3 million immigrants originated from Turkey reside in Germany and 1.383.040 of them have Turkish citizenship and are eligible voters. Remaining former Turkish citizens only hold German citizenship, mainly because Germany forbids dual citizenship. Turkey ensures all citizenship rights of many emigrants who renounced Turkish citizenship to acquire German citizenship by granting them a special status and identification card, called blue card holders. Although there has been an expectation about those having blue cards would able to vote, they were not allowed to do.

- Survey can be another possible data collection method and complementary method, but it emerged as too challenging, because it is costly, necessitating working with a research team and making many arrangements in advance. Even, for interviews and participatory observations, the author faced difficulty and waited a month to get official permission to access electoral stations.

- Most researchers acknowledge that accessibility of data on voters residing abroad is often limited. Accordingly, collecting quantitative and qualitative data is costly and complex to do because of the dispersion of voters in different countries (See Lafleur, and Sanchez-Dominquez, 2014, p. 2). Turks residing abroad cast their votes in person at polling stations abroad or custom gates, which, in contrast with the modality of postal voting, allows for exit poll surveys with emigrants. Thus, the quantitative data is not available.

- Anthony Downs, An Economic Theory of Democracy, (New York: Harper & Row, 1957).

- Joshua Harder and Jon A. Krosnick, “Why Do People Vote? A Psychological Analysis of the Causes of Voter Turnout,” Journal of Social Issues, Vol. 64, No. 3 (2008), pp. 525-549.

- Boccagni, “Reminiscences, Patriotism, Participation: Approaching External Voting in Ecuadorian Immigration to Italy.”

- Boccagni and Ramirez, “Building Democracy or Reproducing ‘Ecuadoreanness’? A Transnational Exploration of Ecuadorean Migrants’ External Voting,” p. 748.

- The focus of their research is to understand the political preferences of emigrants, not really answer main question of this article which is why did citizens abroad cast vote? Their findings may inspire further studies addressing the factors influencing the preferences of external voters of Turkey but not allow for comparison or drawing hypotheses at this stage.

- 40. Lafleur and Sanchez-Dominquez, “The Political Choices of Emigrants Voting in Home Country Elections: A Socio-Political Analysis of The Electoral Behavior of Bolivian External Voters,” p. 21.

- Ibid., p. 21.

- Ibid., p. 22.

- Dorothee Schneider, “Symbolic Citizenship, Nationalism and the Distant State: The United States Congress in the 1996 Debate on Immigration Reform,” Citizenship Studies, Vol. 4, No. 3 (2000), pp. 255-273; Sune Laegaard, “Naturalization, Desert and the Symbolic Meaning of Citizenship,” in Ludvig Beckman and Eva Erman (eds.), Territories of Citizenship, (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), pp. 40-59, p. 56.

- See Rainer Baubock, “Stakeholder Citizenship and Transnational Political Participation,” Fordham Law Review, No, 75 (2007), pp. 2393-2447; Rainer Baubock, “The Rights and Duties of External Citizenship,” Citizenship Studies, Vol. 13, No. 5 (2012), pp. 475-499.

- For a detailed discussion see Ayhan Kaya, “Transnational Citizenship: German-Turks and liberalizing citizenship regimes,” Citizenship Studies, Vol. 16, No.2 (2012), pp. 153-172.

- Boccagni and Ramirez, “Building Democracy or Reproducing ‘Ecuadoreanness’? A Transnational Exploration of Ecuadorean Migrants’ External Voting,” p. 731.

- Baubock, “The Rights and Duties of External Citizenship,” p. 476.

- Carole Jean Uhlaner, “Political Participation,” in N. Smelser and P. Baltes (eds.), International Encyclopedia of the Social Behavioral Sciences (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2001).

- Sidney Verba, Kay Lehman Schlozman and Henry Brady, Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), p. 38.

- Authors’ interview with Arif Unal, 30 July 2014, Köln, Germany.

- “Yurt Dışındaki Oylar Neyi Değiştirir,” Radikal, 18 August 2014.

- Şefik Kantar, “Gurbette İlk Seçim,” Türkses, No. 254 (2014), p. 16.

- Printed interview with Ekrem Ozdemir, CHP Berlin Birliği Başkanı, Zaman, 4 August 2014 p. 5.

- Author’s interview with A. T., 29 July 2014, Dusseldorf, Germany.

- Author’s interview with H. E., 30 July 2014, Cologne, Germany.

- Mark Choate, “Sending States’ Transnational Interventions in Politics, Culture, and Economics: The Historical Example of Italy,” International Migration Review, Vol. 41, No. 3 (Fall 2007), pp. 728-768.

- Author’s interview with A. T., 29 July 2014, Dusseldorf, Germany.

- UETD web site. retrieved July 23, 2014 from http://uetd.info/?p=1140.

- Author’s interview with Y. U., 4 August 2014, Essen, Germany.

- Author’s interview with F. B., 5 August 2014, Frankfurt, Germany.

- Author’s interview with A. K., 30 July 2014, Cologne, Germany.

- Lacy, “Host Country Issues,” p. 149.

- Kathleen Newland, “Refugee Protection and Assistance,” in P. J. Simmons and Chantal de Jonge Oudraat (eds), Managing Global Issues: Lessons Learned, (Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2001).

- According to Turkish authorities, one of the main reasons for the delay of external voting implementation is that Germany that did not allow Turkish immigrants to vote in its soil. However, this claim was refuted by some migration experts with whom the author conducted interviews.

- After the election, German media provided news about the problems encountered in the appointment system. Although some Turkish authorities accused Germany of imposing appointment system, German news did not mention this allegation and associated problems with Turkey’s inadequate planning and the lack of postal voting option. German media seems be pleased by the low- turnout.

- Author’s interview with A. T., 29 July 2014, Dusseldorf, Germany.

- “Deutsche Politiker wollen Erdogan-Auftritt in Köln verhindern,” Zeit Online, (May 16, 2014).

- “Almanya’dan Erdoğan Geçti” Zaman Almanya, (May 25, 2014).

- Author’s interview with M. G., 29 July 2014, Duisburg, Germany.

- Author’s interview with A. T., 29 July 2014, Dusseldorf, Germany.

- Cihan Sendan, “Türkiye Cumhuru ve Başkanı 2014,” (June 05, 2014) retrieved from http://berlinturk.com/index.

php/component/k2/item/40687- türkiye-cumhuru-ve-başkanı- 2014.html#sthash.75tLgTBg.dpuf . - Cem Öztürk, “Almanya Türkleri ve Seçme Hakkı,” Türkses, No. 254 (August 2014), p. 7.

- “Deutsche Politiker wollen Erdogan-Auftritt in Köln verhindern,” Zeit Online, (May 25, 2014).

- Bild, Front Page, (May 25, 2014).

- Author’s interview with M. G. 30 July 2014, Duisburg and author’s interview with Y. U., 4 August 2014, Essen, Germany.

- The article is written before June 7 and November 1 Elections that it why it presented a short analyses of the recent elections. The lack of survey and interview data impedes further analysis on the main research question of the article.

- In total, the number of polling stations increased from 51 to 111. See “Yurtdışı Seçmenler,” retrieved August 13, 2015 from http://www.ysk.gov.tr/ysk/

faces/HaberDetay?training_id= YSKPWCN1_4444010952&_afrLoop= 310926101649607&_ afrWindowMode=0&_afrWindowId= dfjwx3w98_37#%40%3F_ afrWindowId%3Ddfjwx3w98_37%26_ afrLoop%3D310926101649607% 26training_id%

3DYSKPWCN1_4444010952%26_afrWindowMode%3D0%26_adf.ctrl- state%3Ddfjwx3w98_49. - “Yüksek Seçim Kurulunun 2015/1415 sayılı kararı,” retrieved August 13, 2015 from http://www.ysk.gov.tr/ysk/

content/conn/YSKUCM/path/ Contribution%20Folders/ SecmenIslemleri/Secimler/ 2015MV/B.pdf. For distribution of votes by country see http://secim.aa.com.tr/ YurtDisiENG.html. - Citizens abroad were able to cast votes until 25 October at embassies and consulates abroad as well as until November 1 at polling stations on custom gates.

- “İşte AKP’nin Yurtdışı Seçim Beyannamesi,” Sabah, retrieved November 07, 2015 from http://www.sabah.com.tr/

gundem/2015/10/09/iste-ak- partinin-yurtdisi-secim- beyannamesi; “Partiler Yurtdışı Oyları

için Nasıl Çalışıyor,” BBC, ( 22 October, 2015), retrieved November 07, 2015 from http://www.bbc.com/turkce/haberler/2015/10/151022_ yurtdisi_oylar. - “Gümrük Genel Sonuçları,” TRT, retrieved November 07, 2015 from http://www.trtsecim.com/

yurtdisi.html#/?sandikKodu= 9999. - “Yurtdışı Oyları Nasıl Dağıldı?,” Sabah, (November 6, 2015), retrieved November 6, 2015 from http://www.sabah.com.tr/

galeri/turkiye/yurtdisi- oylari-nasil-dagildi/52. - “AKP’nin Seçim Mektubu AGİT Gündeminde,” BBC, (October 22, 2015) retrieved from http://www.bbc.com/turkce/

haberler/2015/10/151022_akp_ mektup_agit; “Hollanda’dan AKP’nin seçim mektubuna resmi kınama,” (October 31, 2015), retrieved November 07, 2015 from http://www.bbc.com/turkce/ haberler/2015/10/151031_ hollanda_mektup_kinama. - “Hollandalı Siyasetçi Wilders: AK Parti’ye Oy Verenler Ülkenize Gidin,” Haberler.com, (November

02, 2015), retrieved November 9, 2015 from http://www.haberler.com/hollandali-siyasetci-wilders-

ak-parti-ye-oy-7838616-haberi/. - Ricard Zapata-Barrero, Lorenzo Gabrielli, Elena Sánchez-Montijano and Thibaut Jaulin, “The Political Participation of Immigrants in Host Countries: An Interpretative Framework from the Perspective of Origin Countries and Societies,” Research Report Position Paper INTERACT RR2013/07, (2013), retrieved August 12, 2015 from http://interact-project.eu/

docs/publications/Research% 20Report/INTERACT-RR-2013-07. pdf.