The sailor rushing from one seaport to the next, transmitting information and news, and the journalist, who, despite undergoing various pressures and difficult conditions, thinks of nothing but the public interest, and struggles to convey the news to people eager to exercise their right to obtain information, may still be the role models of many idealistic journalists today. Yet the media sector’s political, social and legal relationships are quite different from –and more complex– than those found in the early days of journalism. On an individual level, we still undoubtedly come across idealistic journalists who are motivated beyond professionalism to pursue news stories and contribute to society’s right to access news and information. These individuals clearly contribute to democratic processes. On the other hand, the media’s relationships with politics and the economy have changed in accordance with its growth as an industry. With this change, unfortunately, the media has departed from its initial idealism. As a result of this departure, a substantial part of media studies literature today examines the aforementioned relationships, which continuously deepen.1

It is possible to see a similar course of development in the Turkish media industry. The media in Turkey is not independent of power relations in respect to its sources and impacts. Indeed, it does not show any sign of becoming independent in the near future. Beyond any doubt, there are too many methods power holders use to put pressure on the media. When the course of media in Turkey is reviewed, two methods stand out: (1) the direct and physical repression of government control, and (2) indirect and non-physical repression by the ideological framework which surrounds the media and the government alike.

Freedom of the media is generally depicted as a luxury which is easily sacrificed before the ideal and necessity of the “survival of the state,” specifically the constituents of the state which have been determined by the westernization ideal of the Kemalist ideology

In the discussions about the freedom of the media in Turkey, there are adequate studies on the first type of repression, i.e. direct and physical repression by civil or military powers in the government.2 However, the literature that focuses on non-physical and indirect pressure by ideological power, which also surrounds or besieges governments, is insufficient; the reasons for this will be explained subsequently. Despite this, the issue of freedom of the media in Turkey cannot be discussed by excluding the democratization of media perspective, which requires a focus on the non-physical and indirect pressure of official ideology in Turkey. As long as the debate on the freedom of the media in Turkey disregards the democratization of the media, it cannot expose mainstream Turkish media’s political role as a supporter of official ideology. As a result, this inadequate perspective reduces the media freedom issue to a dichotomy with “idealist media” on one side and “degenerate politicians” on the other.

This study will take the above factors into account and discuss freedom of the media and media-politics relations in Turkey by concentrating on the democratization of the media perspective. For this purpose, priority will be given to an analysis of the conditions through which “journalists” come to the fore as a sociological group and an industry in Turkey. Next, for a better understanding of the democratization of the media perspective, the relations between the media sector and the ideological and abstract power that surrounds the media sector –as it once surrounded the civil governments in Turkey– will be discussed. In the conclusion, the current state of the issue of freedom of the media as a structural problem in the country will be addressed with reference to media-politics relations and the democratization of the media perspective.

Before answering the basic questions of this study, a particular point on the method used in this research should be clarified. To support the arguments put forward here, ten interviews were conducted with media professionals in order to have expert opinions from different areas of the sector, such as publishing, journalism, and broadcasting. Some parts of the interviews are directly quoted in this study, while others laid the foundations for the paper’s infrastructure. Since the discussion on the freedom of the media in Turkey has been excessively politicized, in order to have relatively unbiased opinions independent of political considerations, the anonymity of the experts interviewed was guaranteed –their names, therefore, will remain unknown.

The Historical Framework of the Democratization and Freedom of the Media in Turkey

According to Orhan Koloğlu, author of The History of the Press from the Ottomans to the 21st Century, a book frequently cited in media literature which narrates the course of the media in Turkey in the early years of the Republic, the efforts to fully control all types of news circulation under Turkey’s single party regime between 1923 and 1946 were legitimate, because the press was the only way to gain the support of society.3 Unfortunately, Koloğlu’s definition of legitimacy is not uncommon in the course of discussions over the history of the media and freedom of the media in Turkey. Freedom of the media is generally depicted as a luxury which is easily sacrificed before the ideal and necessity of the “survival of the state,” specifically the constituents of the state which have been determined by the westernization ideal of the Kemalist ideology. On the other hand, depending on the political conjuncture, freedom of the media has been regarded as an integral part of achieving a “level of contemporary civilization” in Turkey – especially when it is serviceable for defending the basic principle of Kemalist official ideology. For example, Zeynep Burcu Vardal lists the repressive judgments of legal regulations, such as Takrir-i Sükûn (Law on the Maintenance of Order) and the Press Law, both of which were enacted by the Kemalist single-party regime between 1923-1946. Then they are legitimized by underlining the fact that these legal regulations were inevitable in times of “the totalitarian and authoritarian regimes in Europe” and that they were thus warranted by circumstances. Moreover. Vardal criticizes, the repressive implementations of the Democratic Party (founded in 1946) –which ended the Kemalist single-party governments by winning the 1950 elections– with the declaration that “the mission of the press is to enlighten people when necessary, not to side with the government.”4

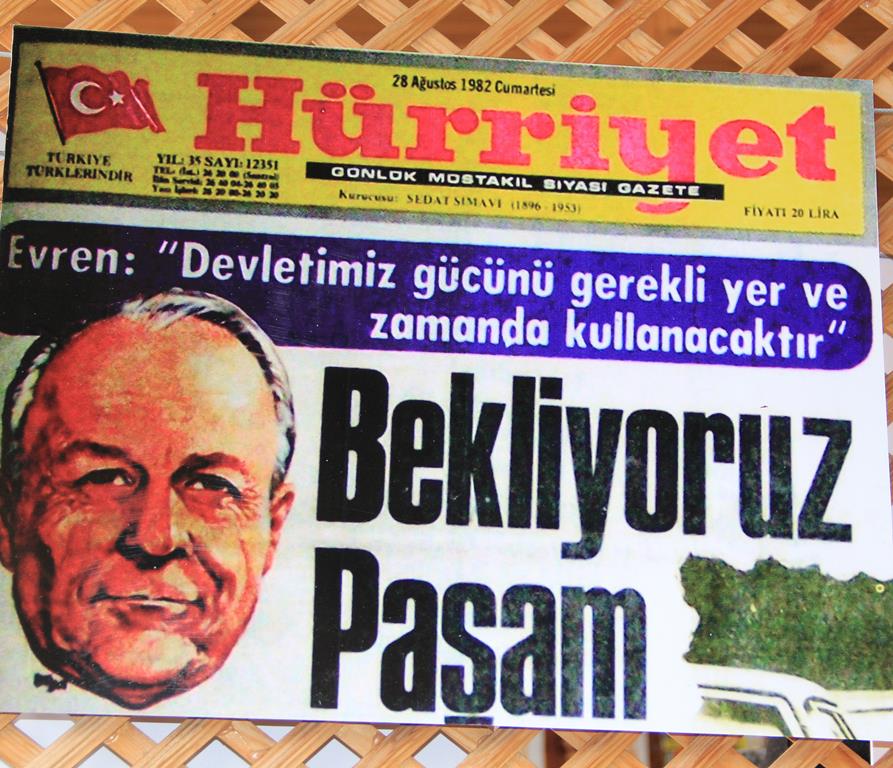

Hürriyet's headline on August 28 1982 addressing Kenan Evran ( the leader of the 1980 military coup) " We are waiting for you General"

Hürriyet's headline on August 28 1982 addressing Kenan Evran ( the leader of the 1980 military coup) " We are waiting for you General"

For a long time, the freedom of the media has been discussed in a uniform manner. The reason the concept of freedom of the media in Turkey has been so easily stretched and twisted is related to mainstream journalism’s socio-political position with respect to its roots. According to Şerif Mardin, social positions in Turkey are determined historically by political processes5 that depend on having access to the state mechanism, not by economic processes that depend on production and share-holding, as in Europe. In this social segregation of traditional masses and pro-modernization elitists, journalists side with the latter who are historically in favor of modernization.6 Considering that journalists, too, like other segments of society, are affected by their historical, cultural and ideological camps,7 it is possible to say that they look at the issue of freedom of the media through the eyes of Kemalist modernization ideology. Thus, the Kemalist single-party government’s pressures on the media are legitimized, even by journalists, by arguments such as “warranted by the conditions of the period,” whereas the practices of the Democratic Party, which represented the traditional masses against the modernizing elitists of the single-party government, are described as “the black days of the freedom of the media.” For example, Sina Akşin, a well-known and frequently-cited scholar of Turkish political history, claimed that although it had many undemocratic actions in the spheres of media, politics and universities,8 Turkey under the rule of the Kemalist single party regime was more democratic than it was during the period of multi-party democracy that started with Democrat Party in 1945.9

From the beginning, Kemalist ideology has given intellectuals, including journalists, two primary and complementary tasks, one of which was the duty of intellectuals towards the state. According to this, intellectuals are accountable to the state for the internalization of reforms and for aiding in the country’s aim to catch up with contemporary civilization. The second duty of the intellectuals was towards the people. This is described by their directive, “to enlighten people” in the following statement, which criticizes the media policies of the Democratic Party government: “The duty of the press is not to side with the government, but to enlighten people by criticizing the government if necessary.”10 According to these two complementary tasks, intellectuals must side with the state in the objective of modernization and in order to elucidate the virtues of the Kemalist regime to the people, who are not yet mature enough to understand the virtues of the new regime and the ideology of modernization.11

The expression “to enlighten” in the above statement is not coincidental and refers directly to “the ideology of enlightenment” in harmony with the spirit of the ideology of Kemalist westernization. When compared to the transcendental and virtuous ideal of enlightenment, which is represented by elites inclusive of journalists, freedom of the media becomes an easily stretchable, twistable and insignificant detail in the aforementioned examples. Moreover, the ideal of enlightenment demarcates the limits of politics as well as those of the media.

Historic Hegemonic Block and the Media as Intellectuals

An analysis of the nature of political power in Turkey allows the discussion of issues relating to freedom of the media to be factually grounded. Power relations in Turkey are not similar to those in a typical democratic regime. Power relations and political reflexes in the single-party period (1923-1946) continued after Turkey had adopted a multi-party political system, while the armed forces and the judiciary, in this period, set de facto obstacles to prevent the formation of a democratic regime. Political parties, as the most important component of the political sphere in a democratic regime, faced attempts at party closure by the high judiciary, and elected governments faced military interventions –coup d’états and memoranda– at different times since the 1960s.12 The military and bureaucratic tutelage over the political system in Turkey restricted the spheres of civil society and the media alike. The military and civilian bureaucracy, a clique of intellectuals with a mission to carry the torch of the Kemalist revolution, and the camp of capitalists who emerged as a result of the attempts to build national capital since the early years of the Republic, controlled the power domain in Turkey and formed a “historic hegemonic bloc,”13 to use the terms of Antonio Gramsci’s theoretical understanding. The ideal of Kemalist westernization constitutes the ideology of this hegemonic bloc; within it, journalists undertake the task of “intellectual and moral leadership.” Gramsci describes intellectuals not according to their capabilities, such as thinking and reaching analytical conclusions, but according to their contributions to building and maintaining hegemony.14 The function of journalists in modern Turkey, from this perspective, conforms with Gramsci’s description of the intellectual.

Correspondingly, in the history of modern Turkey, power is not concentrated in the domain of political parties and governments, but is found in the oligarchy which consists of the bureaucracy, capital holders and intellectuals. The powers that restrict the domain of the media and draw red lines have not been those elected to power by the people through democratic channels, but are rather a product of the bureaucratic oligarchy or the “historical hegemonic bloc” who regard themselves as being above politics and as regime custodians. On the other hand, the majority of the media, in conformity with their role in providing “intellectual and moral leadership,” has not crossed these red lines and has seen no harm in continuing their efforts to support the status quo. It is, therefore, difficult to say that the media in Turkey has been in opposition to the status quo represented by the armed forces and high judiciary. On the contrary, the media has supported military interventions and sided with the powers in favor of the status quo when they confronted powers in favor of change.15 When the media was in conflict with existing governments, it called upon the armed forces and high judiciary to intervene. The media in Turkey has supported the appointed against the elected and the bureaucracy against politicians, and simultaneously has managed to link this into the scope of “media opposition” and “freedom of the media.” For instance, the media overtly stood against the coalition government during the process of the February 28, 1997 post-modern coup,16 which was the second to last of a chain of military interventions in Turkey –the last one being the electronic memorandum of April 27, 2007. In this process, the media supported the military against the political authority by promoting the narrative of protecting and favoring the fundamental principles of the Republic. In actuality, this led to briefings by military staff to journalists at the General Staff Headquarters regarding the direction of their publications.17

The reflexes gained by the media throughout history have played a role in its attitude. During the single-party period, in media-power relations, the former was the “directed” and the latter was the “director.” The media was perceived as a body that must provide ideological support to the regime; the state retained the major information channels, and the activities of the media were, in a legal frame, subject to tight control by official institutions. In the long-term, those prevented the media from expressing opposition to the official ideology of the state and to the actors representing the state. In times of anti-democratic interventions in politics, the media adopted a position in favor of the state, rather than in favor of “society.” The support offered by the mainstream media journalism to the tutelage system has become an extension of the state’s ideological demands in Turkey.

The Turkish media faced complete restriction and strict supervision as news and commentaries were adapted to the conditions of coup periods. Nor was official supervision of the media limited to the single-party or military coup periods. During the Cold War period, for instance, this pressure manifested in the form of “anti-communism.” In the anti-communist political environment of the time, the state noticeably pressured the media, justifying this pressure as the control of “communism propaganda.” One of the journalists journalist who was interviewed for this study described the situation vividly: “At some places, the interpretations of prosecutors and judges were stretched, depending on the individual in charge, and publishing a sentence like ‘steel production in the Soviet Union increased 10 percent’ was considered communist propaganda. Such applications of the law have taken place in Turkey. These can happen when you change limits from an objective domain to a subjective one. For instance, you could not say ‘poverty is increasing;’ it was considered communist propaganda (too).”

Perhaps due to the restrictions on the activities of the media, mainstream Turkish media did not take any political stance against the coups in the post-coup periods, and frequently highlighted the military’s interventions in politics as an act of salvation

A subject that has been ignored in discussions on freedom of the media in Turkey is the years-long restrictions on book publishing. In Turkish political culture, books have been seen as a communication medium with the possibility of carrying “toxic ideas” and for this reason, the state has constantly tried to keep book publishing under its control. “Burning books” was the most radical form of the state’s efforts to block “toxic ideas” during the periods of extraordinary political interventions.

As one publisher interviewed for this study puts it, “Burning a book is not seen only in Hitler’s Germany. A countless number of books were burnt in Turkey as they were not found proper according to the understanding of the official ideology.” For instance, the ban on a total of 453 books since 1949, including the works of prominent figures both in Turkey and in the world, such as Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin, Said Nursi and Nazım Hikmet, was only lifted in 2012.18 Publishers were held accountable for sending their books to prosecutors in order for them to check whether they posed a threat to the “indivisible unity of the State and the Nation.” The state’s “toxic publication” phobia reveals its understanding of propaganda. According to this understanding, when a thought is shared with the public via any communication channel, it has an immediate effect on its audience. For this reason, from the point of view of the official ideology, the circulation of “toxic publications” must be blocked. With time this turned into a reflex, and the legislature has served the aforementioned purpose.

The Mainstream Media and Military Interventions

Perhaps due to the restrictions on the activities of the media, mainstream Turkish media did not take any political stance against the coups in the post-coup periods, and frequently highlighted the military’s interventions in politics as an act of salvation. Turkish mainstream media continued to contribute to the promotion of the military as the “protector of the regime,” “society’s most reliable institution,” “one of the biggest and most effective armies,” and a power center “respectful to democracy.”19 During an interview for this study, a journalist described this period as follows: “The press could not criticize any of the military’s decisions and plans for years. Besides, it was necessary for the press, the mainstream media in particular, to obey the military’s rules. One of the most recent and striking examples of this is the February 28 (1997) Process. This was, to a large extent, a media operation and it was an embarrassing period for the media. Although not its duty, the General Staff gave briefings to universities and the media. It is a disgrace. When the military issued a memorandum to the government, it was backed by the media. The military gave directives to media representatives.” In the same period, the Hürriyet Daily, known as the admiral ship of mainstream media in Turkey, shared the military’s gratitude to Hürriyet for its support to the February 28 Process with its readers. As Hürriyet wrote İsmail Hakkı Karadayı, the Chief of the General Staff, congratulated Hürriyet and said “I congratulate you all. You are making a good service. You are writing very beautiful things. I am saying this sincerely. Your observations are very good and you reason very well.”20

One of these themes, and, therefore, one of the most important obstacles that freedom of the media faces in Turkey, is the “culture of fear” which has developed across the historical continuum

The official ideology that has dominated the political culture in Turkey since the establishment of the Republic is one of the biggest obstacles to freedom of the media. Media in Turkey has remained within the sphere formed by the official ideology and has carried on activities and played a role in spreading this ideology. The media has fulfilled this role by reproducing the themes which form the backbone of the official ideology whose aim is the enculturation of the people in Kemalist modernization.

Fear of the State

One of these themes, and, therefore, one of the most important obstacles that freedom of the media faces in Turkey, is the “culture of fear” which has developed across the historical continuum. The culture of fear, shaped in parallel with the official ideology, has had an impact on the language and the content of the news in the media. Fears –which will be discussed further in this paper– were kept alive by different media and news stories about how unfounded these fears are have faced many difficulties in the publishing process and in trials after publication.

The history of the media in Turkey abounds with many examples of such situations. A journalist, interviewed for this study, portrays the situation as follows: “İsmail Beşikçi was dismissed from university for writing the book, The Order in Eastern Anatolia. He stood trial and faced decades of imprisonment. But what he had written was simply that there were Kurds in the East and they, as any other people, had the right to live. The pious were also in trouble for years. They were labeled as reactionary bigots because they wanted to live according to their religious beliefs. They were repressed. The press has been repressed as well.”

The fear of “separatism” takes the lead among the fears created in Turkey’s political culture; at this point, the Kurdish issue, labeled the “South-East issue,” takes center stage in all discussions. Another journalist, while recounting how he was imprisoned for using the word “Kurd” in the 1970s, said there were times when it was impossible to come across the word “Kurd” other than in the expression “Kürtçü” (pro-Kurdish), which was used as an insult, and that if the word “Kurd” was used in any sentence, it was subjected to investigation by judicial authorities. According to the same journalist, “The legal system in Turkey does not work independently; it is not a power in itself, and acts according to the general policy of the state. To say, ‘There is a Kurdish issue,’ ‘There are grave inequalities,’ ‘Religion is being neglected,’ were grounds for being prosecuted until the 1990s. There even was a problem if you said ‘Kurd.’ Kurds in Iraq were named ‘Peshmerga’ in order not to say ‘Kurd.’”

According to another journalist, who is an academic, the Constitution of September 12 and the coup regime are the main reasons behind the existing problems of freedom of the media. Turkey experienced a de facto relaxation in terms of freedom of the media –although not in legal terms– during the period of the first Motherland Party (ANAP) government (1983-1987). Shortly after, however, struggles with the PKK caused the government to set new red lines for the press and “terrorism crimes” became a further obstacle for the freedom of media. As the Articles 141, 142 and 163 of the Constitution, which had culminated in grave violations of freedom of expression in the past, were abolished in 1992 “communism propaganda” was no longer a media offence. The “Kurdish issue,” i.e. the rising political, legal and cultural demands made by Kurds, and the terrorist attacks of the Kurdish Workers Party (PKK), has been a priority of the Turkish state since 1992, and the media has been expected to act sensitively towards the issue, and even to support the security policies of the state by reducing the Kurdish issue to an issue of public order and terrorism.

Along with the fear of separatism, throughout the history of the Republic there has also been the “danger of religious reaction.” In the 1990s in particular, when a conservative party was elected to power, the repressive effect of the “danger of religious reaction” increased in society in general and especially in the media. In this period, for the first time in the history of the Republic, a political party which expressed itself through Islamic references was elected as the government. The Welfare Party (RP) formed a coalition government with the True Path Party (DYP) in 1996. The RP was regarded as illegitimate by the powers in favor of the status quo that represented the official ideology, and the military seized power. Through the process, which is called the February 28 (Post-Modern Coup) Process, powers backing the official ideology launched a political mobilization utilizing the concept of “religious reaction.” The media became a leading element and through contributions that helped build the myth of the danger of rising religious reaction –on occasion by even fabricating news– it played a key role in the overthrow of a democratically-elected government. In this setting, the Refah-Yol coalition government was toppled and the RP and its successor the Virtue Party (FP) were closed down. Nonetheless, a new political party, the Justice and Development Party (AK Party) –breaking away from this political tradition– came to power in 2002. Turkey’s reforms for its accession to the European Union (EU) were accelerated and restrictions on the media loosened. A journalist interviewed for this study commented that Turkey has experienced a positive course of events in terms of freedom of the media in the last decade as a consequence of the struggle of the Kurds and Sunni Muslims against Kemalism; however, he asserts that this has not been sufficiently reflected in the media.

Without any doubt, freedom of the media can find its place only in a regime that respects social and political democracy; within this scope, the completion of the democratization process in Turkey presents itself as the most critical precondition for the media to be able to begin to act freely

The “culture of threat” targeting journalists must be stressed as one dwells upon the political dimension of freedom of the media in Turkey. This culture can be described as an unlawful attempt at intimidation. As part of the established culture of fear in Turkey, the “attempt of intimidation” against media members is one of the most important ways of controlling the media. The news magazine Nokta under the editor-in-chief Alper Görmüş affected Turkey’s political course by publishing “diaries” of a coup attempt against the AK Party government. Following the publication, the Office of Military Prosecution issued a search warrant for the investigation of the magazine’s headquarters. The owner of the magazine announced that “he no longer had the power to publish the magazine due to the ongoing smear campaign” and closed it down.21 Many journalists are threatened by individuals who claim to be officials and as a result they self-censor their work. Those who are not adequately aware of the atmosphere of political tension and struggle, and the positions of political actors in Turkey, presume that such threats come from the government, and overlook the leading role of the cliques that organized the coup attempts against the government after 2002.

It is misleading to look at the “issue of freedom of the media in Turkey” only via the perspective of the power relation between politicians and the media

Without any doubt, freedom of the media can find its place only in a regime that respects social and political democracy; within this scope, the completion of the democratization process in Turkey presents itself as the most critical precondition for the media to be able to begin to act freely. Besides the tangible physical benefits of assuring freedom of the media, one must not overlook the intangible transcendental benefits for society. Freedom of the media, thus, becomes the most critical indicator of democratization. Freedom of the media, however, cannot be achieved without freedoms of religion, conscience, association, and expression. International institutions, such as the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) and the Parliamentarians Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE), emphasize that freedom and independence of the media is the primary indicator of a democratic society.22

Who Threatens Turkey’s Free Internet?

As freedom of the media in Turkey is being discussed, one of the critical points that must not be ignored is the ban on Internet access. Turkey banned the access to the internet in 2007 when YouTube was blocked following a court order against libelous videos of Turkey’s founder, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.23Access to YouTube was blocked for about two and a half years and the ban was lifted only after a company purchased copyrights of the aforementioned videos and removed them from the internet.24

During the same period, denial of access was imposed on the entire YouTube website via both its domain name and IP address. Following legal and technical improvements with the passage of time, now only specific contents are blocked and bans are implemented on (suspicious or alleged) URL addresses while the rest of the site enjoys free access. In addition, arbitrary bans have been eliminated. According to Law No. 5651, internet-related crimes are currently classified under the categories of sexual assault, promotion of drug use, gambling, profanity, prostitution, procurement of materials that are hazardous for one’s health, and offenses against Atatürk. The course of discussions over the rulings on access bans is informative as it reveals the actors, traditions and mentalities restricting freedom of the media in Turkey. In 2014 and 2015, partial bans issued by court orders on URL addresses for supporting terrorism were categorically criticized by the media and other related parties as instances of the oppression of freedom of the media; in 2007, however, the 2.5-year ban of YouTube on account of insulting Atatürk was subjected to only meager criticism.

Distortion of Turkey and Erdoğan's image by Wikileaks and Stratfor reflected in the headlines of Taraf newspaper.

Distortion of Turkey and Erdoğan's image by Wikileaks and Stratfor reflected in the headlines of Taraf newspaper.

In an interview for this study, statements by a legal expert on Internet Technology (IT), who is also a board member of a sector organization related to the Internet access regime in Turkey, clearly indicate that the bureaucratic tutelage in 2015 was one of the biggest obstacles to freedom of the media in Turkey: “Contrary to general belief, one of the most widely used pleas for bans on Internet access in Turkey today are insults to Fethullah Gülen, not to Atatürk or the president. With his countless numbers of lawyers, Fethullah Gülen takes action to block access to news content criticizing him on the Internet. In fact, the same petition is used from one court to the other in a different city until a judge who is a member of a Gülen group is found to decide on the issue.”

Even after the recent improvements, the restrictions on access to the Internet in Turkey still exhibit the limits of freedom of the media. However, as seen in the examples above, the official ideology, lateral sub-state organizations and bureaucratic groups pose greater threats to freedom of the media than politicians and norms of supervision.

Conclusion

For a democratic state administration and society, freedom of the media carries a symbolic meaning and weight. Normatively, the political sphere which has legislative and executive powers in hand stands to gain the utmost advantage by applying restrictions on freedom of the media through laws and state apparatuses. For this reason, when it comes to restrictions on freedom of the media, politics as a source of power and politicians as actors become the prime targets of attention.

If freedom of the media in Turkey is viewed from a government control perspective, there are still some restrictive areas such as the material and moral damage suffered by many journalists as a result of lawsuits and the repressive mindset in the field of law, which is still effective despite recent reforms. The Justice and Development Party is frequently accused by its opponents of forming an authoritarian single-party regime. However, the general election on June 7, 2015 stood witness to the fact that the AK Party’s political power can be diminished by voters. Nonetheless, the structural problems of freedom of the media still persist. As seen in the example of the 2015 elections, the ways and directions that elected politicians use their power can change by democratic methods, as their power can be delimited or taken away completely. Still, it is incomparably more difficult to determine and control the indirect and abstract power centers than to check and control the media and elected politicians.

For this reason, it is misleading to look at the “issue of freedom of the media in Turkey” only via the perspective of the power relation between politicians and the media. The more comprehensive and profound problem areas for the freedom of media in Turkey do not come from the sphere of elected politicians but from the sphere of the hegemonic power of the Kemalist official ideology. It restricts the powers of elected political forces in Turkey as it restricts the media and spans across cultural, ideological and economic planes. Therefore, besides being independent from the power of politics and protected against it, media in Turkey should also be independent, neutral, freed and protected from the official ideology and the hegemonic power. For this reason, the discussion of freedom of the media in Turkey should include the democratization of the media perspective as well as the freedom of the media perspective.

Endnotes

- For examples of the relationship between the media, the economy and politics see Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky, Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Media (New York: Pantheon Books, 1988); A. Raşit Kaya, İktidar Yumağı: Medya, Sermaye, Devlet (Ankara: İmge Bookstore, 2009).

- For this perspective, see Hıfzı Topuz, II. Mahmut’tan Holdinglere Türk Basın Tarihi (İstanbul: Remzi Bookstore, 2003).

- Orhan Koloğlu, Osmanlı’dan 21. Yüzyıla Basın Tarihi (İstanbul: Pozitif Publications), p. 114.

- Zeynep Burcu Vardal, “Türkiye’de Basın Özgürlüğü ve 2003 Yılı Sonrası Uygulamalar,” unpublished dissertation, Institute of Social Sciences, İstanbul University, (2014), pp.116-129

- Şerif Mardin, “Center-Periphery Relations: A Key to Turkish Politics?” Daedalus: Journal of American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Vol. 102, No. 1 (1973), pp. 169-190.

- Nilgün Gürkan, Türkiye’de Demokrasiye Geçişte Basın (1945-1950) (İstanbul: İletişim Publication, 1998), p. 67.

- Gürkan, Türkiye’de Demokrasiye Geçişte Basın (1945-1950), p. 67.

- Sina Akşin, “Atatürk Döneminde Demokrasi,” Ankara Üniversitesi Siyasal Bilgiler Fakültesi Dergisi, Vol. 47, No. 1 (1992), p. 247-249.

- Akşin, “Atatürk Döneminde Demokrasi,” p. 251-252.

- Zeynep Burcu Vardal, “Türkiye’de Basın Özgürlüğü ve 2003 Yılı Sonrası Uygulamalar,” p. 129.

- For this perspective of the relationship between intellectuals and the Republic, see Ahmet İshak Demir, Cumhuriyet Dönemi Aydınlarının İslam’a Bakışı (İstanbul: Ensar Neşriyat, 2004), pp. 49-58.

- “Timeline: A history of Turkish Coups,” Al-Jazeera, (April 2012), retrieved from http://www.aljazeera.com/news/europe/2012/04/20124472814687973.html.

- Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 2005), pp. 57-58.

- Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, p. 9.

- It is possible to read the performance of the press during the coup periods through the material published in newspapers. For this perspective, see Hayati Tek, Darbeler ve Türk Basını. (Ankara: Elips Books, 2007).

- “Manşetlerdeki 28 Şubat/Darbeye Giden Yolda Medyanın Rolü,” SDE, (February 2013), retrieved from

http://www.sde.org.tr/tr/newsdetail/mansetlerdeki-28-subat-darbeye-giden-yolda-medyanin-rolu/

3257. - İsmail Çağlar, “Good and Bad Muslims, Real and Fake Seculars: Center-periphery Relations and Hegemony in Turkey through the February 28 and April 27 Processes,” Unpublished Dissertation, Leiden University, Department of Turkish Studies, (2013), p. 60.

- “453 Kitap Artık Yasak Değil”, Sabah, (December 6, 2012), retrieved from http://www.sabah.com.tr/kultur_sanat/2012/12/06/453-kitap-artik-yasak-degil

- For the position of the press, see L. Doğan Tılıç, Utanıyorum ama Gazeteciyim: Türkiye’de ve Yunanistan’da Gazetecilik (İstanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2009), pp. 313-319.

- Alper Görmüş, Büyük Medyada Ergenekon Haberciliği (İstanbul: Etkileşim Publications, 2011), pp. 218-219.

- For the story of “the coup diaries” and the news magazine Nokta under editor-in-chief Alper Görmüş see Alper Görmüş, Büyük Medyada Ergenekon Haberciliği, pp. 63-112.

- Denizhan Horozgil, “İfade ve Basın özgürlüğü Çerçevesinde Soruşturma Evresinde Yayın Yasakları Üzerine Bazı Tespit ve Değerlendirmeler,” Hacettepe University Faculty of Law Magazine, Vol. 2, No. 2 (2012), p. 149.

- “Youtube’a Erişim Engellendi,” Haber Türk, (2008), retrieved from http://www.haberturk.com/ekonomi/medya/haber/51956-youtubea-erisim-engellendi.

- Murat Tumay, “Denetim ve Özgürlük İkileminde İnternet Erişimi,” SETA Analysis, No. 113 (2015), p. 12.