Introduction

The MHP increased its votes by about two million in Turkey’s June 7 general elections and its vote share jumped to 16 percent from 13 percent in the preceding elections. The rise of the MHP can be summarized in a few points. First of all, Turkish nationalism rose as a social reaction to the increasing votes going to the pro-Kurdish HDP; that evidently helped the MHP land on its’ feet. The MHP received votes primarily from youth who voted for the first time, and from electors of other parties. For instance, votes shifted from the AK Party to the MHP to a certain extent, as their party grassroots overlap on some matters. AK Party votes, to a large extent, shifted to the MHP in the western part of the country. The main opposition party CHP lost a substantial number of votes to the MHP as well. There are some specific reasons behind this, rooted in local politics, but there are also more general reasons.1

Indeed, the MHP has become one of the strong actors of the political arena, in large part due to its gradual transformation into a center-right party, the rise of nationalist sensitivities as a reaction to escalating terrorism by the PKK, the revival of nationalist objections to EU-Turkey relations, and the negative economic impacts of the neoliberal globalization process. Most importantly, the AK Party’s way of handling the Kurdish issue played a key role in the MHP’s receiving more votes in June, as it did in the similar context of the general elections of 1999.2

Given the November elections results it may be argued that the MHP unsuccessfully handled its tarnished image as “a Nay-Sayer” party in public opinion and in the media

Despite the MHP’s increasing prominence in Turkey’s political arena, the snap elections on November 1 paid off for the AK Party government when the ruling party surprisingly won a high number of votes against a dramatic decrease in the MHP vote. In the wake of the June 7 elections, Turkey’s agenda was preoccupied by escalating acts of terror and failed coalition talks. The MHP’s attitude, during the coalition talks in particular, resulted in a new label for the party, namely “Nay Sayer,” as the MHP became the target of criticism for evading responsibility during a critical time when the country could not afford a power gap. Indeed, the need for stability and a strong government were underlined and uttered more frequently by the public in the interim between the June and November elections because of the mounting terror incidents. The emergence of such critical problems requiring immediate solutions led to the holding of a snap election [mandated by the Constitution] on November 1 and indirectly led to a decrease in the MHP vote.

It is helpful to take a closer look at these fluctuations in voter choice, first toward, and then away from the MHP, in order to understand the dynamics of the June and November elections, and how the MHP-AK Party rivalry may play out in the future. In the June 7 elections, a substantial number of conservative-nationalist constituents shifted to the MHP as a result of depreciation stemming from the 13-year-old single AK Party government and discontent stemming from some AK Party policies. After all, the cultural grounds to which the AK Party and the MHP appeal largely overlap in terms of some themes and sensitivities. Due to this overlap, some electorates who are not hardline AK Party supporters or not its staunch proponents might have been attracted to the MHP.

In contrast to this, the vote loss the MHP suffered in the November 1 elections mainly stemmed from the elections’ confrontational agenda. In fact, it may be argued that the labeling of the MHP as a “Nay-Sayer” party grabbed public attention. MHP was accused of facilitating the failure of the coalition talks after June 7. In other words, the perception was raised that the unsuccessful negotiations were largely due to the attitude and discourses of the MHP. Such a perception was reinforced when the MHP closed the door to a number of demands and suggestions proposed by the opposition. This situation generated the perception that, in the political arena, the MHP was incapable of implementing any political course, so going against the nature of a political party’s raison d’étre. Given the November elections results, in which the MHP suffered substantial losses compared to June, it may be argued that the MHP unsuccessfully handled its tarnished image as “a Nay-Sayer” party in public opinion and in the media.

While the MHP struggled with these issues of perception on the political front, escalating acts of terror increasingly dominated the agenda in Turkey, and led to urgent demands for stability and a single-party government. Accordingly, under the pressure of these immediate and pressing concerns, the diversity of votes and the resulting political landscape following the June 7 elections lost its desirability for the vast majority of voters. Accordingly, voters with conservative-nationalist sensitivities who chose the MHP on June 7 opted for the AK Party in November, regarding this to be the option for stability in Turkey; the need for stability and unified action clearly emerged as an important reason behind the MHP’s vote loss on November 1.

In order to understand why the MHP failed to provide the electorate with a sense of safety and stability, it is helpful to look at the party’s basis and traditional stances. In regard to its main reference and emphasis, the MHP has built a discourse and political practice on the basis of Turkish nationalism. A chain of discourse themes such as state, security, terror, identity politics, foreign policy, globalization and the economy circulate around the basis of the MHP’s nationalist emphasis and theme. Simply put, the MHP’s hard-core ideology rests on Turkish nationalism and occasionally reflects a Turkish-Islam synthesis. In this regard, since the 1990s, the MHP has experienced –albeit slowly– a certain transformation, characterized by a shift towards the center, while developing political practices and discourses by remaining loyal to its generally stable and fixed political position.

It is possible to interpret this positioning in two ways. At first glance, the MHP’s posture may be qualified as a consistent and sustainable principal attitude. Yet, the fact remains that voters did not flock to this tenet in the interest of stability. At second glance, then, the MHP’s positioning may be interpreted as an insistence on a resistant and persistent stance unresponsive to changing conditions in Turkey and in the world. In its perceived inability to chart a political course for Turkey, the MHP appeared incapable of creating policies appropriate for the changing conjuncture of Turkey’s needs and goals, developments or problems, and seemed lodged in a fixed perception of the world.

As Turkey’s political landscape continues to evolve, will the MHP be perceived as a bastion of nationalistic stability? Or an outmoded relic, clinging to an old dream of national, ethnic unity, which is being replaced by Turkey’s positioning in a new, diverse and global community? How strongly and to what extent voters share the general political stance and discourse of the MHP, which are rooted in the main theme of Turkish nationalism, is another important question.3 The answers of these questions are elaborated in this study.

A Brief History of the MHP’s Ideological Evolution

The process of the MHP’s ideological fermentation dates back to the Ottoman-Republic axis. The MHP emerged as a political entity when its founding-father, the late Alparslan Türkeş, participated in the Republican Peasantry Nation Party (CKMP) during a party convention in 1965.4 His goal was to reorganize the party and to set new objectives according to his own political ideology. In parallel with this, Türkeş was selected as the new chairman of the party at a CKMP extraordinary convention on August 1, 1965. As soon as Türkeş became the chairman of the party, the CKMP adopted a pan-Turkish and anti-communist discourse ornamented with Islamic references. “The nine-light doctrine,” formulated by Türkeş in 1967, was adopted as the principle doctrine and the party’s name was changed to the MHP at an extraordinary party convention in 1969.5 This name change may be read as a development symbolizing a change in the party’s dominant character with the arrival of Türkeş. In other respects, it is possible to say that the MHP has been identified with Türkeş and has become an indivisible whole since then.6

Formulated as “anti-communism” in the party’s development process, the MHP’s mission has been a key element of its development since the late 1960s. The MHP joined the anti-communist struggle in the 1970s with a self-assumed mission of being “a Pro-State Civil Power.” However, the MHP’s mission and self-identification with the state failed due to the March 12, 1971 military intervention in Turkey. The MHP experienced yet another shock due to the September 12, 1980 military coup d’état and the attitude towards the party during the period of the 1980-1982 military government. In fact, the period of the September 12 coup was experienced not as a military takeover that would conform to the imaginations of the MHP’s Ülkücü (Idealist) grassroots, but rather as a period in which the MHP and Türkeş, together with other parties and party leaders, were taken into custody. Although the MHP’s top officials tried to identify with the mission of the September 12 coup d’état with the expression, “the man is in the cell, his ideas are in power” at first, this resulted in an identity and legitimacy crisis among the party grassroots of the Ülkücü Movement. Constructed by the Aydınlar Ocağı (the Heart of the Enlightened) in the post-September 12 period, the doctrine of Turkish-Islamic Synthesis gave body to the main dynamic of the MHP’s ideological mixture. In other words, the determining factor behind the process of change in the Ülkücü Movement’s political orientation and discourse in the post-September 12 period was Islamization.7

The MHP reads the Kurdish issue through the perspective of terrorism and security, and has adopted a discourse of fear as a means of persuasion

In the 1990s and afterwards, the existing pan-Turkism in the MHP corpus was revived by establishing relations with Central Asian Turkic Republics as a State policy, in consequence of the Soviets’ disintegration, PKK terrorism and the Kurdish issue. In this process, the MHP overcame the obstacles associated with the notion of Islamization after 1980. Simply put, it is possible to say that the reactivation of the pan-Turkism genes in the MHP did not mean a total break-up with Islam, but stood out again as a dominating component of identity.8 Following the death of Türkeş, the MHP selected Devlet Bahçeli as its new chairman in 1997. His period of leadership played a critical role in the party’s adoption of a low-key position towards the center. The MHP currently employs an ideological mixture overlapping with the discourses of pan-Turkism, Islamism and, to some extent, Kemalism.9

The Constitutional Referendum on September 12, 2010 offers a source of critical assessment for the MHP’s modus operandi. The structure of the Constitutional Court and of the Supreme Council of Judges and Prosecutors (HSYK), the Supreme Military Council decisions, the establishment of the Office of Ombudsman, and the trial of military members behind the September 12 coup d’état set the content of the referendum process. Conservative-nationalist groups negatively viewed the MHP’s playing ball with the CHP and its nationalist grassroots who led the “Say No” campaign during the referendum process. In other words, the “Say No” campaign for the 2010 Constitutional Referendum was perceived by members of conservative-nationalist groups, some of whom share the MHP’s political and cultural ground, as an attempt to block –through bureaucratic State mechanisms– the legitimate political powers elected by the People.

In brief, one can say that the referendum process predominantly progressed through a dichotomy of a drive for more democratization as opposed to a tutelary regime. The MHP’s attitude along the way was characterized by political maneuvering. Nonetheless, this maneuvering was regarded as a political positioning that partly intersected with the leftist-nationalist and Statist reflex of the CHP due to the highly sensitive content of the referendum, such as democratization reforms, the demilitarization of the system, and indictment of the coup d’état leaders.

As far as the MHP’s “statist reflexes” are concerned, how the party managed the state-society balance during an election campaign for the general elections on June 12, 2011 would give an idea of this aspect of their platform. Conservative actors, including the AK Party, have realized the fact that the MHP is sandwiched between the Kemalist-State and reformist conservatives. Then Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan criticized the MHP for failing to hear the demands of conservatives, and accused it of teaming up with proponents of the Kemalist-State.10 In this regard, it is possible to say that as a result of statist reflexes in several problem areas, the MHP has to some extent made changes in its political attitude and discourse, although it remained aloof to the state in the post-coup period after 1980.

The MHP’s rather perpetual political language and practice clearly surface in the context of the Kurdish issue. All along the line, the MHP has not seen this matter as the “Kurdish issue” at all, nor associated it with an ethnic group’s demands for cultural rights.11The MHP’s approach to the issue could most aptly be summarized as a conjunction of separatism, counter-terrorism, law-and-order, and security.12 The MHP’s securitized discourse and approach to the Kurdish issue seems to be the dominant theme that has been used by the party in political communication strategies in general elections since 2007. A holistic approach to television advertisements, being one of the important instruments of political communication reflecting political languages and codes of political parties, reveals that the MHP reads the Kurdish issue through the perspective of terrorism and security, and has adopted a discourse of fear as a means of persuasion.13

Another characteristic of the MHP’s political language appears in the party’s Statist perspective or discourse, which is used in different problem areas, the Kurdish issue in particular. It is possible to say that MHP-State relations have been a rather obscure, complex partnership. In this regard, the “State” has always occupied a key position among the MHP’s identity components. Although it seems paradoxical, the ideal of one’s serving the State is a distinctive characteristic of MHP’s principle of Idealism. Pro-Islamic political parties are generally positioned at the “periphery”; the MHP, however, reflects an image of a rather State-centered party in the Turkish political spectrum. For that reason, even though the terms of “hardline nationalism” or “Islamism” are central components of the ideological mindset of the party, the term “Statism” better characterizes the MHP.14

The MHP positions itself on a ground of “categorical opposition” to the AK Party, the Kurdish issue and the reconciliation process

The assessments that are made here so far focus on several findings about the codes of the MHP’s political language. Because the “Kurdish issue” intersects with the problem of Turkey’s domestic terrorism, which played such a crucial role in the November 2015 elections in particular, we will now turn to an examination of how the MHP shaped this issue, and other key concerns on Turkey’s agenda, in its campaign discourses. From now on, more specific analyses will follow about the party’s political communication strategies and the political discourse, in particular between the June 7 and November 1 elections.

Method

This study applies the method of content analysis, and examines the MHP’s total of 55 different television advertisements that are archived15 on its official web site for the June 7 and November 1 elections.16 Thematic analysis is used as a method for the analysis of the MHP’s election manifestos prepared for the two elections. The types of messages given in the ads are analyzed. As political communication literature is examined, one will recognize two different ways of categorizing political advertisements: (1) positive and negative advertising17 and (2) thematic and image advertising.18 Along with positive political advertising which praises parties, negative political advertising which criticizes other parties or their candidates is frequently used in political campaigns.19 Moreover, dual categorization is used to differentiate between two, often preferred types of appeal in political ads as it is shown in the table 1: rational appeal and emotional appeal. Lastly, the use of slogans and emblems in the MHP’s political ads are categorized as: slogan and emblem, no slogan, no emblem, or none.

Frequency distribution and cross table analyses are applied in the analysis of data gathered for this study. To maintain reliability, the same content is coded by the writers of this piece at different times and places, and the writers have reached agreement on 90 percent of the data obtained. As part of this research, answers have been sought for some questions such as, “What is the ratio of positive and negative advertisements used by the MHP?”; “What kind of negative ads are mostly used?” “Which topics are focused on political television ads?”; “What kind of persuasion appeal is applied?” and “What kind of images are used?”

The MHP’s “Meaning Map” in the June 7 General Elections

MHP’s election manifesto for the general elections on June 7 is entitled, “Social Repair and a Peaceful Future.” The MHP’s slogan of “Walk with Us Turkey” is used to reach out to electorates. Following the preface, the manifesto begins with a section titled “From the Eclipse of Reason to the Reasonable State,” and continues with an array of sections on the dynamics of the century, the national view, a global power vision for Turkey, an understanding of power and democracy, policies, and building the future. Under the heading of “Policies” are included subheadings such as: Justice, Fight against Corruption, Economic Targets and Policies, Regional Development, Security and Defense Policy, and Foreign Policy.

In the introduction, the MHP identifies its objective of coming to power alone, introduces policies to be implemented in addition to several other objectives such as “economic recovery and revival,” “repair of the State administration and restructuring,” gaining “international prestige and being influential”, implementing “a judicial system faithful to justice,” and providing citizens with “a life with security, law and order, retaliation for attacks against the Unitary National State, and free from terrorism.” A large part of the introduction is allocated to matters that the MHP refers to as the basis of its policies, such as the struggle against “corruption, injustice, corrupted foreign policy, disintegration, separation and treason.” The party calls people to unite under its auspices, by using the slogan, “Walk with Us Turkey.”

In the first section, titled “From the Eclipse of Reason to the Reasonable State,” the MHP uses negative and negating language about the election period and overtly targets the ruling party. As part of this negative descriptive language, the MHP claims that the governing party exploits the national willpower to cover up corruption, injustice and separatism. Again, in the same discourse, the MHP terms the AK Party’s approach to the Kurdish issue as “political concession policies” and draws attention to the fact that the “terrorism issue” has been redefined as an identity issue. In conjunction with these discourses, the MHP also makes allegations against the AK party government and accuses the ruling party of “gradually setting the ground for the elimination of the Turkish Nation.”20

Although the MHP uses rational and positive language in the election manifesto while elucidating the solid promises it intends to deliver in various areas, it clearly adopts a negative attitude reference to AK Party policies, particularly the AK Party’s approach to the Kurdish issue and the “reconciliation process.” In this regard, the MHP positions itself on a ground of “categorical opposition” to the AK Party, the Kurdish issue and the reconciliation process. Indeed, the MHP terms the current political period as an “eclipse of reason,” and describes the future MHP-governed period as a “reasonable State.”

The MHP continues to term the reconciliation process the “treason process”, and claims that none of the objectives declared by the AK Party to the public have been met

As an extension of this matter in the election manifesto, under the heading of security and defense policy and counter-terrorism, the MHP makes negative innuendos about the AK Party’s policies and performance. Accordingly, the MHP promises in the manifesto to end “the understanding of fight putting only terrorism in the center” and “negotiations with terrorism.” In this section, referring to the HDP, the MHP states that “to present terrorists as the people’s representative,” “to voice the demands of terrorists as those of the people,” and “the attempt to create an artificial ground for terrorism through ethnic and religious instigations” are part of the “actions in support of terrorism.”

A more positive language is used in the manifesto under the counter-terrorism section, indicating that the MHP will definitely distinguish who the citizen is, who the terrorist is, who is innocent and who is not. In the manifesto, the MHP also stresses its determination to apply the methods of a State of Law.21 Yet another important but rather specific point is the MHP’s approach to the December 17-25 incidents which have still remained critical to the country’s agenda although they occurred in 2013. The MHP describes the incidents in the context of “corruption, bribery and black-money probes.”22 Other images in political advertisements are used as negative implications to highlight the same issues; thus the MHP aims to refresh voters’ memory of the corruption allegations against the AK Party. The MHP’s principal attitude towards a new constitution and understanding of democracy is also among the critical issues mentioned in the election manifesto. Democracy is viewed not only as a political regime but also as a way of life. Accordingly, the MHP stresses the necessity of finding the broadest ground of consensus for a new constitution, and that the terms of general protection and freedoms should be concentrated rather than general limitations.

As for a new constitution, “One Nation, One State,” “Unitary Structure” and “Turkish Identity” are uncontestable issues for the MHP, which completely opposes a multi-partite nation, collective rights based on ethnicity, granting status to different languages and cultures other than Turkish, the concept of “Türkiyelilik” (being from Turkey as opposed to being Turkish), the replacement of the citizenship bond with the concept of the Turkish nation, education in different mother tongues, and the implementation of a system of self-governing regions. In this context, the MHP disapproves of the presidential system and its derivatives, which have been frequently discussed since the Elections of 2011, stressing that the parliamentarian system is the best regime for Turkey.23

The MHP, on one side, tries to grab voters’ rational attention and emphasizes what they will gain if they vote for the MHP; and on the other side, it weighs in with emotional appeal while trying to persuade electors by fear

In the section entitled “Nation and the National Willpower,” the MHP clearly emphasizes that the legitimacy of political powers is based on national willpower, and that national willpower comes into existence in the National Assembly. Also, the MHP announced that intervention in a democratic regime and into a parliament’s constitutional authorities from the outside, irrespective of the justification and thought, is unlawful and unacceptable. After expressing its understanding of national willpower, the MHP expresses disapproval of the tendency toward authoritarianism on the pretext of national willpower.24

The discussions here about the MHP’s election manifestos for the 2015 general and snap elections expose what kind of a meaning map and political practice the party has in mind for some of Turkey’s problem areas. Given its success in the June 7 elections, its stance clearly struck a chord with a significant number of voters.

The MHP’s “Meaning Map” in the November 1 Snap Elections

The MHP participated in the November 1 snap elections with an updated version of the manifesto prepared for the June 7 general elections. The first thing that attracts attention in the updated manifesto is a change of heading and slogan. The MHP titled the June manifesto, “Social Repair and a Peaceful Future,” but changed it to “A Peaceful and Secure Future” in November. As for the slogan, June’s “Walk with us Turkey” was replaced in November with, “The Future of the Country.” The MHP stressed the “peaceful future” theme in June, and the “trust” theme in November. By looking into these two themes together, one sees that the MHP tried to give a message in the November 1 snap elections that an environment of peace and security in the future of Turkey is achievable with the MHP.

After November 1st elections, MHP for the first time became the fourth party and has to sit at the edge of the parliament, a place where generally the HDP members used to sit. | AA PHOTO / SALİH ZEKİ FAZLIOĞLU

After November 1st elections, MHP for the first time became the fourth party and has to sit at the edge of the parliament, a place where generally the HDP members used to sit. | AA PHOTO / SALİH ZEKİ FAZLIOĞLU

When the introduction is put under a microscope, one can see that the November manifesto is almost identical in outline with that of June. What makes the November manifesto different is that there is an assessment, in the introduction, about the landscape after the June 7 election and in the post-election process. In the scope of this assessment, the MHP stated in the November 1 manifesto that the single AK Party government was ended by electors in the June 7 general elections, and the people’s message for the parties was to reach consensus for a coalition. However, the MHP also stated that Turkey was being pushed into yet another election period because of the “biased” and “destructive” attitude of the President, along with his concerns about the political future and accountability.

In addition, the MHP stressed in the November 1 manifesto that terror had escalated and that the security of the election was under threat, as the State failed to establish authority in some regions, and that Turkey had decided for another election in such an atmosphere. The MHP positioned itself as a party that makes necessary calls in this fragile situation and prioritizes the State and the Nation. In this context, the MHP adopted an incriminating language against the AK Party and the President, blaming them for the general condition of the country.25

In the section entitled, “From the Eclipse of Reason to the Reasonable State,” the “opening” and “reconciliation” processes were overtly described as “processes of treason”; the MHP stressed that these developments had turned into a survival issue for the State and the Nation. A new discourse used in this section seems to be constructed by a reference to statements issued by some AK Party officials and the President. According to this discourse, the MHP stressed in the manifesto that the PKK had exploited the process, termed a “reconciliation bluff,” for armament, munitions and militant pile-up and that the AK Party government had overlooked this fact so as not to harm the process. The same section includes a clear confession on the part of the government and AK Party officials, who had made accusations against the MHP that the reconciliation process had taken a bad turn because of them. The MHP also noted in the document that the “treason” and “separation” characteristics of the reconciliation process are evident; therefore, a new approach is needed for counter-terrorism efforts.26

Further on in the same section, another high point grabs the attention: the MHP reveals its approach towards the coalition issue and related discussions after the June 7 general elections. Accordingly, the MHP read the June 7 election results as a coalition request from voters, and held the AK Party and the CHP responsible for the differences of opinions among the coalition actors. It is also stated that the MHP prioritizes the interests of the nation over those of the party, and that is why it refused to join a possible coalition and did not support a minority government or the scenarios for an election government either; it stands ready to take responsibility for any long-term coalition government only if certain preconditions are met.

In the scope of these preconditions, the “indivisible integrity of the State with its territory and nation”, “consolidation of the unitary structure” and “moral politics” are listed. Despite all these, the MHP states that its political interlocutors could not agree on the idea of coalition and refused the MHP’s demands in advance. In this section of the manifesto, the MHP positions itself against the actors who tried to label the MHP as a “Nay Sayer” in the post-June 7 period. In this regard, the MHP explains that the failure to form a coalition is not their fault. Without explicit reference to any particular party, the MHP implicates others as “political addressees,” “those who cannot digest the coalition idea,” “those who blow up coalition alternatives through any kind of political moves and plots,” and “perception engineers.”27

Although some additions are seen in several sections, as the MHP worked to address the unique concerns facing the Turkish public following the June elections, the November 1 manifesto is almost identical with that of the June 7. For instance, in the November manifesto, the MHP’s first ruling period is entitled, “Building Calm, Repair and the Breakthrough Period.” Under the heading of “Public Administration,” it announces that the manpower needed for State and government reform will be provided through public employment. Again in the same section, the MHP states that civil servants who prioritize the interests of any political entity, ideology or group shall be subject to sanctions without compromise. Another addition to this section is that professional organizations and associations shall not be allowed to take any political and ideological stance. The reason for this is that the MHP regards such partisanship as a deviation from the aim of the associations.28 Considering that professional organizations and associations are part of civil society, this would prevent the aforementioned institutions from taking a stance on social and public issues.

The MHP’s frozen and rooted discourses about the Kurdish issue and the reconciliation process obviously and naturally dominate the political language of the party

In addition to the heading of economic target and policies to the November 1 manifesto, the MHP states that economic problems are gradually increasing while production is decreasing in Turkey. Another noteworthy point in this section is that the MHP believes that markets have been subdued due to Turkey’s failure to form a single party government after the June 7 general elections. The MHP tries to reinforce this claim by comparing dollar exchange rates before and after the election. Through a negative reference to the AK Party, the MHP states that structural reforms could not be undertaken in this period, which has made the economy vulnerable to political risks.

The MHP also added several items about taxation to the November 1 manifesto. Namely, unitary and fair taxation shall be given importance, in line with the principles of confidentiality of income tax and the taxation of individuals according to their financial strengths. In addition, full tax exemption for employees on the minimum wage and partial tax exemption for all others ( the amount of their incomes equivalent to the minimum wage shall be exempted from tax).29 Another addition in the November 1 manifesto addresses the struggle with unemployment. It is stated that the MHP will establish an interrelation between education and employment, and higher education planning will be made accordingly.

To this end, graduates of vocational and higher education systems will be employed, and the MHP will take necessary measures for currently unemployed university graduates to find jobs. Under this heading, the party also states that human capital will be directed to sectors in need of employees, and the education system will be rearranged accordingly.30 With this promise given in the manifesto, the MHP touches on one of the most problematic issues in Turkey, and sends messages to the youth to gain their support. For the solution of this problem, the MHP argues that the education system should be redesigned to meet employment needs, in accordance with employment areas.

Conservative-nationalist voters who are not among the grassroots of any particular party and who mostly preferred the MHP on June 1 changed their minds and voted for the AK Party on November 1 with an expectation of stability

Some discussions and additions under the counter-terrorism heading in the November 1 election manifesto should also be noted. In this regard, the MHP continues to term the reconciliation process the “treason process”, and claims that none of the objectives declared by the AK Party to the public have been met. The MHP terms this process as a “scandal” clearly targeting the national unity; it announced in the manifesto that this scandal will be brought to an end, and that the “treason process” will be completely eliminated. Under this heading, yet another interesting point is that the MHP accuses those civil servants and politicians who do not join in counter-terrorism efforts, or who ignore them in order not to harm the reconciliation process, of being “traitors.” It is stated in the document that the MHP will take legal action against them.31

One last addition to the November 1 election manifesto is about the media. The MHP states that media outlets misinforming people, or publishing or broadcasting biased news for political perception management, will be subjected to legal and administrative punishment. Two opposite terms “pro” and “anti” are used for the media, both of which are also often used in public opinion. The MHP makes an assessment at this point stating that the aforementioned media outlets, rather than adopting an understanding of free and independent media, exploit media power and ignore universal media ethics.32

Consequently, the MHP’s November 1 elections manifesto is identical with that of the June 1 elections except for a few insertions. The former is an updated version of the latter in terms of philosophy, election promises, and statements about the situation in Turkey. Updates or insertions usually work to prove how the MHP is right about the unfolding events in the country. In this context, the party highlights that their evaluations on the reconciliation process in particular, and in relation to this, the party’s approach to counter-terrorism based on security concept are confirmed. There are also a few new promises made in the document. While the MHP may have been banking on consistency as a sign of stability, it is possible that not appearing responsive enough to Turkey’s changing conditions in the interim period, lost them some votes in November.

Comparative Analysis of the MHP’s TV Ads in the June 7 and

November 1 Elections33

During the June 7 general elections period, 58.1 percent of the MHP’s 31 different kinds of television advertisements consisted of positive, and 41.9 percent of negative ads. Apparently, the MHP’s election strategy was to join in the race for a possible single party power, carry its criticisms about the AK Party into its television ads and to try to keep its promises at the forefront. In other words, in its use of media as one of the most powerful political communication instruments, the MHP did not totally invest in negative advertisements, but rather focused on the solid benefits that voters would have obtained under the MHP. During the November 1 snap elections period, however, the MHP focused more on negative ads; 33.3 percent of 24 television advertisements were positive and 66.7 percent were negative ads. Did this turn toward negativity contribute to the MHP’s losses in November?

In both election periods, the MHP designed negative advertisements and built them on implied comparisons. In other words, the MHP implicitly criticized its contenders, or their candidates, during both the June 7 and November 1 elections. In this kind of negative ad, who is criticized and which party is found incapable are left for the audience and the voters to decide. In fact, the MHP applied inference as its main negative election campaign strategy in previous election terms as well; figuring out who or which party was criticized was left to voters to discern.34

In regard to the themes of the political advertisements examined, the MHP mostly used transportation and the economy, both of which have become chronic issues in Turkey, along with the corruption claims made after the December 17-25 operations against the government and the ruling party. The MHP stressed calm and trust in its television ads to lower the tension that had escalated due to these claims. As in the past election periods,35 “national unity” was one of the most important themes used by the MHP in the June 7 elections. On the other hand, 71.4 percent of the MHP’s advertisements on the economy had positive content as opposed to 28.6 percent negative ads. Again, all television ads with the theme of corruption, violence, the coalmine accident, terrorism, and unemployment have negative contents. Democratic rights, justice and equality, social security, health and agriculture are included in the MHP’s positive ad campaigns, all of which reflect on the Turkish people’s gains during the past MHP governments.

As for the November 1 elections period, 60 percent of the television ads with economic content are positive and 40 percent are negative. All of the MHP ads with corruption content are negative ads. Most of the ads on terrorism are also negative (80 percent). Again, in the same election period, the MHP often used themes of corruption, the economy, terror and democratic rights in its television advertisements.

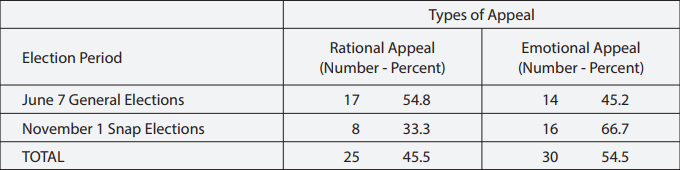

Table 1: Use of Appeal Types According to Election Period

Rational appeal outweighs emotional appeal in these ads, accounting for 54.8 percent and 45.2 percent, respectively, in the MHP’s ads broadcast in the June 7 elections period. As the results clearly reveal, the MHP, on one side, tries to grab voters’ rational attention and emphasizes what they will gain if they vote for the MHP; and on the other side, it weighs in with emotional appeal while trying to persuade electors by fear. In the November 1 elections, the MHP preferred emotional appeal in its television advertisements. Emotional appeal is used in 16 of 24 ads (66.7 percent).

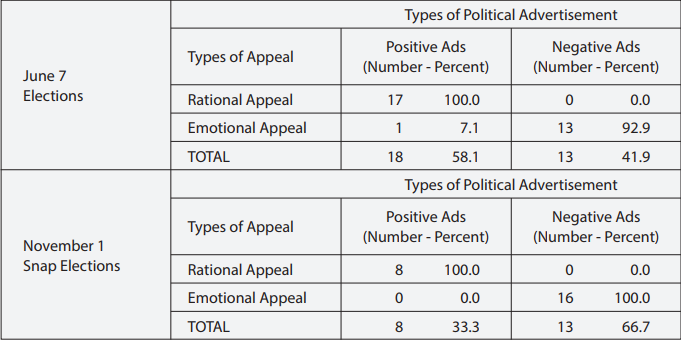

Table 2: Type of Appeal Used According to Political Television Advertisements

The types of appeal used in the ads during the June 7 elections period reveal that all of the ads concentrating on rational appeal are positive advertisements. Again, 92.7 percent of the emotional appeal ads are negative, compared to 7.7 percent positive advertisements. Accordingly, the MHP used rational appeal and engaged the electorates’ minds while reminding voters what they had gained during the past MHP governments, but preferred emotional appeal in its negative ads. Differentiation is observed after the analysis of a Chi Square test (X2= 27.18; df= 1; p< .001). In other words, the types of appeal used in the MHP’s political ads meaningfully differ. The types of appeal used in the November 1 elections period differ (X2= 24.00; df= 1; p< .001). Cross tables are analyzed, and rational appeal dominates all of the positive ads and emotional appeal outweighs negative ads.

Many people bought, to a certain level, the discourse that being a “Nay Sayer” translates into incapability to command and drive a political course

Another finding is that music is used as a key complementary element in all of the television advertisements prepared for the MHP in both elections periods. As is well known, music has a strong social stimulation effect in political campaigns. Music is also critical for political parties or candidates to inform electors, direct their attention to the content of a message, help them easily remember the message given, and encourage them to take a position.36

Compared to other election terms, the leader’s image in MHP advertisements is less visible. In fact, the leader’s photograph or image in advertisements is a complementary element that makes it easier to understand or support the message intended. In political ads on television, a photograph of MHP Leader Devlet Bahçeli walking in a suit is used to create a strong and charismatic leader image, and harmony is intended with the slogan of “Walk with Us Turkey.” In contrast to the June 7 election period, most of the MHP’s political advertisements during the November 1 elections include the leader’s image (66.7 percent). In November, the MHP tried to criticize its contenders on televisions and create a strong leader image by including discourses about what it promised to voters.

Lastly, for the June 7 elections, the party’s slogan and emblem are used together in 41.9 percent (13 ads) of television advertisements, while in 58.1 percent (18 ads) of the ads only the emblem is seen. In the November 1 elections, however, the party’s slogan and emblem are used together to complement the discourse in a major part of 24 ads (91.7 percent).

Conclusion and Discussion

A comparison of the election manifestos indicates that the November 1 election manifesto is simply a partially updated version of the June 7 manifesto. Other than the updates and the insertions, both manifestos are identical as far as their contents and the approaches to the issues are concerned. The first updates, that catch the eye, are a change in the title of the November 1 election to “A Peaceful and Secure Future” and that the slogan of “The Future of the Country” is chosen. To this end, the MHP seems to position itself as the future of the country. The question we pose is: Was the MHP banking on consistency in order to appeal to the public as a stable choice, and repeat its June election win? For this reason, did the MHP appear unresponsive –or not responsive enough– to Turkey’s changing needs between June and November? We will look next at the MHP’s attempts to address the calculus of issues that came to prominence in the interim between the June and November elections.

The problem areas that needed urgent care on Turkey’s agenda, (from the perspective of the voters) could tolerate neither a power gap nor political infertility

Perhaps the most remarkable difference in the November 1 manifesto is how the MHP interprets the situation in Turkey in the post-June 7 elections. Accordingly, the MHP refers to the remarks of the President and the AK Party while it explains the problem of escalating terrorism and the PKK’s stockpiling of resources for an armed struggle during the Reconciliation Process. To put it differently, the MHP emphasizes the role and the responsibilities of the relevant actors in the resolution process and in the post-June 7 elections period as it evaluates the situation in Turkey characterized by escalating terrorism. Therefore, the MHP makes a self-evaluation in the November 1 manifesto about its righteousness and legitimacy in the approach and discourse adopted towards the above problem areas. Another critical point the MHP touches upon in the same manifesto is who should be held accountable for the failure to form a coalition government after the June 7 elections. Accordingly, the MHP implies that, first of all, others tried to create a perception of the MHP and its leader as “Nay Sayers,” and to imply that its “political addressees” are accountable for the failure to form a coalition.

A general assessment would be that the MHP’s frozen and rooted discourses about the Kurdish issue and the reconciliation process obviously and naturally dominate the political language of the party. This principal and dominant discourse based on the MHP’s theme of Turkish nationalism, not only in general but also in the political communication and campaign processes during election periods, becomes the leading theme. The MHP, of course, talks about its concrete performances and policies in the areas of the economy, social rights, justice and public administration, and offers discourses regarding its vision of Turkey and the world, its understanding of power, and topical developments in politics. In this regard, the MHP views the Kurdish issue as a problem area resting on three main arteries including terrorism, separatism, and security, rather than as an identity, ethnic and cultural issue. Therefore, the MHP’s stagnant and rooted discourse on these areas can be coded as a chain of negative and threatening statements about the Kurdish issue, the reconciliation process, the future and the unity of Turkey.

It would be inaccurate to say that the MHP’s entire discourse and attitude on this particular issue is problematic, but it is also wrong to say that the MHP’s discourse and attitude are accurate and valid as a whole. In other words, it would be misleading to adopt a “wholesale approach” to this problematic area, which has been a lasting chronic and painful issue. Instead, a more proper perspective would be gained by multiple readings concentrating on the course of the issue’s development through the historical process, its cyclical character, and the approach and the aim of the involved actors. For instance, it would be examined, as a critical point of reference, whether the HDP, one of the main actors of this problem, aims to satisfy its identity demands and cultural rights through democratic politics on a legitimate political ground or whether it follows the course of a separatist movement. Whether or not the legitimate elected political actors are capable of keeping terrorism and violence at arm’s length arises as a main factor weakening or strengthening political demands, arguments and legitimacy.

Concordantly, the MHP’s way of reading this issue, which is a dominant theme in its discourse and approaches in general, and in election terms in particular, would be evaluated in conjunction with in-depth analyses of the aforementioned points of reference. In the presence of electors, starting with ideological affiliations, both the discourses used by political actors through the medium of various political communication instruments, and the chains of discourses and discussions about the above reference points and their derivatives –both of which are propagated to broad masses by the media– are sharp and clear. However, which dimension of the Kurdish issue gains weight periodically out of its many different dimensions, becomes another critical point. To put it differently, the characterization of the issue in terms of acts of terrorism and the language of violence, instead of demands of rights and identity, shape the language and reflexes of society and politics.

From this viewpoint, this issue is addressed by the MHP as “Social Repair and a Peaceful Future” in the June 7 elections manifesto. Through a cross-reading, even such a naming itself reveals that for the MHP a period of a single party AK Party government means “depression” and “an uneasy future under threat.” Granted, the terms “Kurd” and the “Kurdish issue” are not mentioned in the election manifesto; this is regarded as an issue of terrorism and security by the MHP. In line with this, the MHP views the AK Party’s relevant policies under the Reconciliation Process as “policies of political concession.”

Similarly, the MHP, in both election campaigns, predominantly focused on the corruption claims in the aftermath of the December 17-25 operations against the government. To ease the tension caused by these corruption claims, the MHP emphasized peace and trust in its television advertisements. As negative discourse predominated in the MHP’s television advertisements, with a focus on issues of corruption, violence, the coalmining accident, terrorism and unemployment, a positive understanding is reflected in its advertisements with the themes of the economy, democratic rights, justice and equality, social security, health and agriculture, and the gains for citizens during the past MHP governments. In the light of the aforementioned statements, the MHP would be effective in motivating its grassroots by such a political communication strategy and campaign. However, in order to come to power, it would be more effective for the party to adopt a new political language and strategy that prioritizes change through new discourses and new actors.

While this article has focused on a comparison of the MHP’s electoral discourse in the June and November elections using its electoral manifestos and TV ads, the article has also aimed at shedding light on the question of why the MHP’s electoral results differed in the two elections. Hence, the aforementioned assessments on the election manifesto of the MHP updated prior to November 1 may be identified as the main factors to explain the party’s loss of votes from June 7 to November 1. In fact, it may be advocated that the increasing demands from a substantial part of constituents for stability became critical in Turkey, where acts of terror and relevant political rows have gradually intensified. Thus, the assessment would be that conservative-nationalist voters who are not among the grassroots of any particular party and who mostly preferred the MHP on June 1 changed their minds and voted for the AK Party on November 1 with an expectation of stability. In this regard, terrorism and acts of terror played a determinant role in the vote-shift from the MHP to the AK Party on November 1.

Perhaps as a less effective factor is that the MHP’s attitude –during the talks for a possible coalition, after the failure of talks, and during the formation of an election government– were portrayed as a contradiction with a political party’s raison d’être. In other words, many people bought, to a certain level, the discourse that being a “Nay Sayer” translates into incapability to command and drive a political course. This notion, in fact, became quite compelling for some constituents who had previously voted for the MHP, albeit they were not among the entrenched MHP grassroots. Furthermore, this particular attitude of the MHP during the period of June 7-November 1 created the impression that the MHP, among other opposition parties, remained incapable of coming up with an alternative in the post-June 7 elections arithmetic. The reason is that although the AK Party suffered a vote-loss preventing it from forming a single party government, other political parties also failed to benefit from the AK Party’s loss to find a tangible power alternative. In conclusion, constituents who had withdrawn their votes from the AK Party due to some reservations and cast for the MHP on June 7 had a change of heart once more and ended up voting for the AK Party on November 1. On the other hand, it may also be reasoned that the problem areas that needed urgent care on Turkey’s agenda, (from the perspective of the voters) could tolerate neither a power gap nor political infertility. In sum, a combination of the above factors in varying degrees played a determinant role in the explanation of the MHP’s vote loss in the period of June 7 to November 1.

Endnotes

- Nebi Miş, Ali Aslan, Murat Yeşiltaş and Sadık Ünay, 7 Haziran 2015 Seçim ve Sonrası: Siyaset, Dış Politika, Ekonomi, (İstanbul: SETA, 2015), p. 18.

- Mustafa Altunoğlu, “7 Haziran Seçimi’ne Doğru Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi,” SETA, (2015), retrieved from http://file.setav.org/Files/

Pdf/20150523223619_126_mhp_ analiz.pdf, p. 8. - From a communications perspective, there is critical reservation as to how well the MHP addresses the Kurdish issue, security and terror issues, the reconciliation process, Turkey’s economic policies, and globalization. The picture reveals key indicators to show how well the MHP communicates its messages to voters regarding the aforementioned issues.

- Bülent Aras and Gökhan Bacık, “The Rise of Nationalist Action Party and Turkish Politics,” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, Vol. 6, No. 4, (2000), p. 49.

- Derya Kömürcü and Gökhan Demir, “Nationalist Action Party and the Politics of Dissent,” Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, Vol. 5, No. 8, (2014), p. 553.

- Jacob M. Landau, “The Nationalist Action Party in Turkey,” Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 17,

No. 4, (1982), p. 589. - Tanıl Bora and Kemal Can, Devlet Ocak Dergâh: 12 Eylül’den 1990’lara Ülkücü Hareket, (İstanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 1991), pp. 46, 87-88, 137, 243.

- Mustafa Altunoğlu, “7 Haziran Seçimi’ne Doğru Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi,” SETA, (2015), retrieved from http://file.setav.org/Files/

Pdf/20150523223619_126_mhp_ analiz.pdf, p. 12. - Sultan Tepe, “A Kemalist-Islamist Movement? The Nationalist Action Party,” Turkish Studies, Vol. 1,

No. 2, (2000), pp. 60, 69. - Gökhan Bacık, “The Nationalist Action Party in 2011 Elections: The Limits of Oscillating between State and Society,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 13, No. 4, (2011), p. 178-179.

- Mustafa Altunoğlu, “7 Haziran Seçimi’ne Doğru Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi,” SETA, (2015), retrieved from http://file.setav.org/Files/

Pdf/20150523223619_126_mhp_ analiz.pdf, p. 20. - Ibid, p. 20.

- Hürriyet, Milliyet, Sabah, Zaman. 9/11/13/19/21 July 2007.

- Ziya Öniş, “Globalization, Democratization and the Far Right: Turkey’s Nationalist Action Party in Critical Perspective,” Democratization, Vol. 10, No. 1, (2003), p. 39.

- http://www.bizimleyuruturkiye.

com.tr/index.php?sayfa=9. - Yusuf Devran, “Medya Bağlamında 22 Temmuz Seçimleri,” Seçim Kampanyalarında Geleneksel Medya, İnternet ve Sosyal Medya Kullanımı, Yusuf Devran (ed.), İstanbul: Başlık Publishing Group, (2011), pp. 129, 164. Political advertisement broadcasts were prohibited in Turkey until the recent general elections. Accordingly, the use of radio and televisions in election campaigns are regulated in Articles 52 and 55 in Law No. 298. The aforementioned articles overtly state that political advertisements of political parties are not permitted on private television, but the broadcast of such advertisements on state television shall comply with certain rules. However, Article 31 of the Law No. 6112 on the Establishment of Radio and Television Enterprises, which came into force on February 15, 2011, has been re-regulated as “Media service providers may broadcast advertisements of political parties and candidates during the election period to be announced by the High Election Board, until the time the broadcast prohibitions will start.”

- Lynda Lee Kaid and Anne Johnston, “Negative versus Positive Television Advertising in U.S. Presidential Campaigns, 1960-1988,” Journal of Communication, Vol. 41, No. 3, (1991), pp. 53-64.

- Anne Johnston and Lynda Lee Kaid, “Image Ads and Issue Ads in U.S. Presidential Advertising: Using Videostyle to Explore Stylistic Differences in Televised Political Ads from 1952 to 2000,” Journal of Communication, Vol. 52, No. 2, (2002), pp. 281-300.

- Oya Tokgöz, Seçimler Siyasal Reklamlar ve Siyasal İletişim, (Ankara: İmge Publications, 2010), p. 302; Şükrü Balcı,“Türkiye’de Negatif Siyasal Reklamlar: 1995, 1999 ve 2002 Genel Seçimleri Üzerine Bir Analiz,” Selçuk İletişim, Vol. 4, No. 4, (2007), p. 122.

- The Nationalist Action Party, June 7, 2015 Election Manifesto, retrieved from http://www.bizimle

yuruturkiye.com.tr/usr_img/usr/beyanname/buyuk/beyanname. pdf, pp. 1-22. - Ibid, pp. 228-234.

- Ibid, pp. 74-77.

- Ibid, pp. 55-64.

- Ibid, pp. 55-64.

- The Nationalist Action Party, November 1, 2015 Election Manifesto, retrieved from http://mhp.org.tr/usr_img/

mhpweb/1kasimsecimleri/ beyanname_1kasim2015.pdf, pp. 5-6. - Ibid, pp. 17-19.

- Ibid, pp. 19-23.

- Ibid, pp. 91, 96.

- Ibid, pp. 97, 111.

- Ibid, pp. 179.

- Ibid, pp. 240-241.

- Ibid, pp. 261.

- Most of the MHP’s total of 31 television advertisements for the June 7 general elections were 10-second spots. As the durations of advertisement statics are examined, it is seen that the MHP’s television advertisements last a minimum of 10 seconds and a maximum of 55 seconds, the average being about 15 seconds. The reviewed television advertisements are categorized as follows: 26 ads last 1-15 seconds, 2 ads last 31-45 seconds, and 3 ads last 46-60 seconds. The MHP communicates its messages to its audience mostly through advertisement spots on television, and the party prefers a short yet effective message design strategy in order not to bore its audience. The statistical results of the television advertisements broadcasts for the November 1 snap elections indicate a minimum of 12 seconds and a maximum of 59 seconds spots. Again, in the November 1 election, as in the June 7 election, the MHP preferred short television advertisements. In fact, 18 of a total of 24 advertisements consist of 1-15 second spots.

- Şükrü Balcı and Onur Bekiroğlu, “2007’den 2015’e Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi’nin (MHP) Siyasal İletişim Stratejilerinin Analizi,” in Türkiye’de Siyasal İletişim 2007-2015, İsmail Çağlar-Yusuf Özkır (eds.), (İstanbul: SETA, 2015), p. 105.

- Ibid, pp. 85, 90, 101.

- Nuran İmik Tanyıldızı, “Siyasal İletişimde Müzik Kullanımı: 2011 Genel Seçim Şarkılarının Seçmene Etkisi”, Selçuk İletişim, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 100-103.