Since 2000, internal and external developments have forced African leaders to play a more active role in sustaining peace and security in conflict areas and increasing security relations with the EU. Importantly, the establishment of the AU in 2002 and NEPAD in 2001 were historic events for the continent, affecting relations between Africa and the global actors, in particular the EU. The two global actors have developed common security strategies to prevent conflicts and wars and sustain peace and security. The EU foreign and security policy towards Africa has begun to change since the first Africa-EU Summit held in Cairo, Egypt, in April 2000. Previously, the EU’s engagement in Africa had mainly been in terms of trade and aid. During the first Africa-EU Summit, the Cairo Declaration and the Cairo Plan of Action were accepted by both African and European leaders, and a wide range of issues were handled. The Summit played a significant role in changing the EU’s traditional foreign policy towards Africa, and it was the first time the EU, inter alia, had dealt with security issues facing Africa.

In addition, there are other preeminent historical events that influence the EU’s security policy towards Africa, namely the Cotonou Agreement and the European Security Strategy (ESS). The Cotonou Agreement was signed between the EU and the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States (ACP countries) in June 2000, in Cotonou, Benin. It has contributed to the birth of the Strategic Security Partnership between Africa and the EU. Though the Agreement mainly focused on poverty reduction, economic and trade cooperation, and integration of the ACP countries into the global economy, its approach did not constitute an entirely comprehensive security policy towards the ACP countries. In 2005, a revised Cotonou Agreement dealt with international cooperation against terrorism and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction (WMD), followed in 2010 by another revision that brought a different perspective to the EU’s security policy towards the ACP countries, underlining the interdependence between security and development. However, for all its revisions, the Agreement developed a global security policy rather than one specific to Africa. Its most important feature was that the EU linked the security concept with international economic and trade cooperation within the ACP countries.

Economic interests of the EU member states as well as the new global challenges and the emergence of new actors in Africa have played an important role in developing the EU’s security policy in Africa

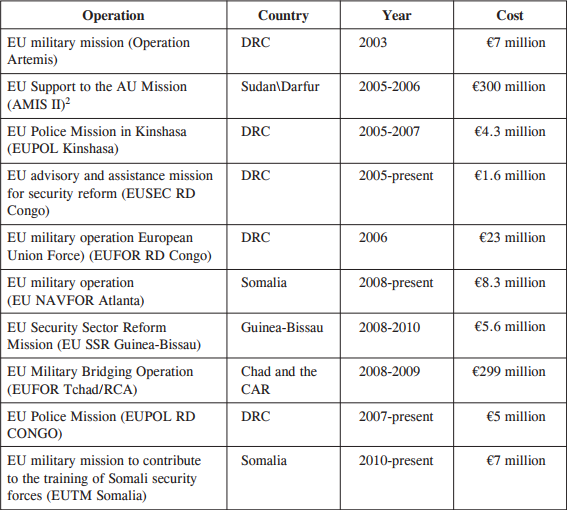

In the history of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) of the EU, the European Council adopted its first common “European Security Strategy” (ESS) in 2003. The title of the ESS was “A Secure Europe in a Better World,” and it identified the key threats facing the EU, defined its strategic goals, and established its political implications towards Europe. The ESS has played a strategic role in increasing security relations between Africa and the EU. One of the most indispensable new security policies of the ESS was that the EU should strengthen its relations with international and regional organisations in order to play a more dynamic role in the maintenance of international peace, security, and stability. The ESS provides the momentum for the establishment of strategic partnership with Africa in the areas of peace and security, intended to: (a) strengthen its relations with African regional and sub-regional organisations in Africa; (b) deal with poverty reduction, the lack of good governance, and the root causes of the conflicts and wars in Africa and (c) use economic, social, diplomatic and political instruments to effectively sustain peace and security in Africa. Since the European Council adopted the ESS in 2003, the EU has begun to get involved more actively in conflict areas in Africa. It has deployed 10 peacekeeping operations in the different parts of Africa since 2003, as table 1 shows.

Table 1: The EU Civilian and Military Operations in Africa1

The EU allocated €300 million for the AU Mission in Sudan in 2005 and 2006. Even though the EU did not authorise a peacekeeping operation in Sudan, its financial and political support played a critical role in strengthening the AU peacekeeping operation in Sudan. The EU’s largest peacekeeping operation in Africa has been deployed in Chad and the CAR in 2008 and 2009. The EU also earmarked €299 million for its peacekeeping mission in Chad and the CAR called EUFOR Tchad/RCA. Importantly, the EU for the first time deployed its own peacekeeping operation in Africa named “EU military mission (Operation Artemis) in the DRC.” The EU Security Sector Reform Mission contributed to sustaining peace and security in Guinea-Bissau in 2008-9. Four of the EU’s African peacekeeping operations are still up and running. While two of them are in Somalia, the others are operating in the DRC. It is important to underline that the adoption of the ESS by the EU members in 2003 was a strategic action for the future of the EU foreign and security policy towards Africa in order to play a more dynamic role in the fields of peace and security. Even though each EU member has different political and economic interests in Africa, the EU members developed a common security policy towards Africa with the ESS.

The EU Foreign and Security Policy in Africa

The EU developed different foreign and security policies according to different regions or countries in Africa. For instance, the EU increased its security relations with the Maghreb countries through the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) in 2004. Likewise, it strengthened its foreign and security relations with the countries in East Africa, including Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kenya, Somalia, Djibouti, Sudan, and Uganda through the Strategy for the Horn of Africa in 2006. And the EU built up special bilateral relations with South Africa through the EU-South Africa Strategic Partnership in 2007.

Since the post-independence era, the EU has continued to pursue its economic interests in Africa through diplomatic means, such as bilateral agreements, conventions and summits

The emergence of the ENP was notable in building up a new security approach towards the Maghreb countries. It was established in 2004 and consisted of 27 EU member states, and 16 EU neighbouring countries, including the Maghreb countries. The fundamental objective was to strengthen socio-economic and political relations with neighbouring countries. It is also among one of the most crucial foreign policy instruments of the EU within the CFSP. The ENP built up two important security policies towards the Maghreb countries, namely to reinforce cooperation among its countries to effectively combat against the new security threats and challenges, and achieve more political involvement in conflict prevention and crisis management. The EU’s economic interests have played an important role in changing the EU’s foreign and security policy towards the region. For example, the EU sold weapons amounting to the value of €343.7 million to Libya in 2009.3 The most important EU members exporting weapons to Libya were France, Italy, the UK, and Germany.

With regard to the EU’s policy towards East Africa, the EU has a strong historical and economic relationship with the countries in East Africa, especially with its geo-strategic location in Africa and internationally. According to the Commission of the European Communities:4

… a prosperous, democratic, stable and secure region is in the interests of the countries and peoples of both the Horn of Africa and the EU. However, an uncontrolled, politically neglected, economically marginalised and environmentally damaged Horn has the potential to undermine the region’s and the EU’s broad stability and development policy objectives and to pose a threat to European Union security.

Thus, the EU adopted a regional strategy towards East Africa in Brussels in 2006, entitled “Strategy for Africa: an EU regional political partnership for peace, security, and development in the Horn of Africa.” Even though making a security policy for East Africa is a challenging task for the EU, for complex reasons that include conflicts and wars in the region, it has been necessary. Consequently, it has developed a special political relationship with the sub-regional organisation in East Africa, which is the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD).

South Africa has also played a significant role in developing the EU’s foreign and security policies in Africa. South Africa has an influential role at regional and international levels in sustaining international peace, security, and stability. It has played significant roles in the establishment of the AU and the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD), and was a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council during the period 2007-2008. Meanwhile, it is a member of the G20, it is the largest trading partner in Africa, and one of the most important trading partners for the EU in the world. Both the EU and South Africa have developed a common security perception, including countering international terrorism, stemming the proliferation of WMD, fighting organised crime, and taking measures to reduce drugs and human trafficking. Though the EU’s main relations with South Africa are based on economic cooperation, in particular through the Trade, Development and Cooperation Agreement (TDCA) signed in 1994 and effective in 2004, cooperation between the EU and South Africa in the fields of peace and security has increased since 2004.

Economic Factors Affecting the EU’s Security Policy in Africa

Europe has deep historical relations with Africa. Indeed, it has social, economic, and political interests dating back to the 15th century. France is the largest trading partner for the African countries within the EU members.5 France was also the largest of the EU’s exporters to Africa, with €20 billion in 2010.6 In addition, Britain7 has special economic, political, and historical relations with South Africa. The total rate of its exports and imports have reached over 40 percent, making it one of the most important commercial partners for the UK in Africa and in the world.8 Africa has been a significant trade market for the UK, particularly South Africa, Nigeria, Kenya, Ghana, Angola, Botswana, Mauritius and Namibia. Germany’s economic interest has recently increased in Africa. For example, it became the largest exporter of conventional weapons to African states between 2003 and 2006, with an amount of $900 million. Meanwhile, its total trade reached €33 billion in 2008. Exporting energy supplies to African states has been one of the most substantial commercial activities of Germany in recent years since 2003.9

Since the post-independence era, the EU has continued to pursue its economic interests in Africa through diplomatic means, such as bilateral agreements, conventions and summits. The 2005 EU Strategy for Africa (2005:2) stated that the EU was still highly dependent on Africa’s natural resources, for instance importing 85 percent of its vegetables, fruits, and cotton from the continent, making it the largest trading partner for Africa.10 Cathelin11 points out that the EU members’ commercial interests undermine the development of the EU’s security relations with Africa. The EU encounters difficulties formulating its security policy, as it oscillates and has to choose between idealism and realism.

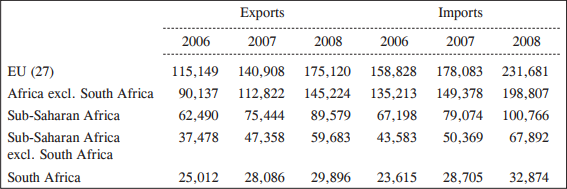

Table 2 (below) shows that the EU has increased its trade volume since 2006 with Africa. While the EU’s exports to Africa in 2006 were 115,149 billion dollars, they increased to 175,120 billion dollars in 2008. However, the global economic crisis has affected the EU’s economic relations with Africa. For example, its exports and imports to Africa dropped in 2009. While the EU’s imports to Africa decreased by 33 percent in 2009 its exports also fell by 10 percent.

Table 2: European Union’s Overall Trade with Africa (2006-2008) (in million dollars)

Source: Adapted from UNCTAD Handbook of Statistics 2009.

External Dynamics Affecting the EU’s Security Policy in Africa

External factors that have an impact on the EU’s security policy towards Africa consist of the new emerging global actors in Africa, the role of global powers, the emergence of a new political climate in Africa, and the 911 terrorist attacks on the USA.

The New Emerging Global Actors in Africa

The appearance of the new global actors in Africa, especially China, India, Brazil, and Turkey, has had an extensive impact on the global powers’ foreign and security policies towards Africa. The new actors’ engagement in Africa has particularly influenced three important areas: (1) political relations between African states and global actors, (2) economic relations between African states and global actors, and (3) relations between the African regional organisations and global actors.

The new actors have actively strengthened their economic and political relations with both African governments and African organisations, such as with the AU, the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD), and the IGAD. Firstly, Africa is of great strategic importance to China’s economic interests, with the latter importing 26 percent of its oil from Africa, with which its total trade reached $72 billion in 2007, and $100 billion in 2008.12 Though China’s total trade with Africa decreased by $91.07 billion in 2009, because of the global economic crisis, it remained Africa’s largest trading partner in 2009. In 2010, China’s total trade with Africa reached $114.81 billion.13

The new actors’ engagement in Africa has particularly influenced three important areas: (1) political relations between African states and global actors, (2) economic relations between African states and global actors, and (3) relations between the African regional organisations and global actors

India has also increased its commercial ties with the African states. Whereas India’s total trade with Africa was $25 billion in 2006-7, it was almost $45 billion in 2010.14 Brazil’s trading relations with Africa have also boomed significantly in recent years; the trade volume reached $26 billion in 2008. While its imports from Africa increased by 39 percent in 2007-8, its exports only increased by 18 percent in the same period.15 Turkey has actively strengthened its economic and political relations with Africa since 2005. While Turkey’s total trade with Africa was $16 billion in 2008, it reached $30 billion in 2010. Furthermore, Turkey has strengthened its political relations with Africa since 2005, opening 15 new embassies in 2010, attaining the current total of 27.16

The importance of the concept of strategic partnership has begun to increase significantly in Africa since 2000. Whereas global actors had no aim to establish a strategic partnership with the continent of Africa until 2000, and they pursued traditional economic and political relations, they have resorted to building a strategic partnership with Africa based on the new actors’ increasing relations. For instance, China declared 2006 as a “year of Africa,” and established a new strategic partnership with the continent. In 2006, Brazil also built a strategic partnership with this continent, followed in 2008 by India. Turkey also announced 2005 as a “year of Africa” and set up a strategic partnership with the continent of Africa.

Against this background, the EU has particularly changed its foreign and security policy towards Africa since 2000, acknowledging 2005 as a “year of Africa,” and adopting the “EU Strategy for Africa” in 2005. Trade and economic relations between Africa and the EU has gained since 2000. While EU exports to Africa were $112 million in 2009, they reached $127 million in 2010, despite the effects of the global crisis of 2007. At the same time, EU imports from Africa have increased, from $112 million in 2009 to $135 million in 2010.17 In parallel with this boom in trade relations, security cooperation between Africa and the EU has risen greatly since 2000. The EU has created different strategic partnership models to consolidate its economic, political, and historical relations with the continent of Africa against the continent’s new emerging global actors. It can be arguably said that the new emerging actors in Africa have strengthened their economic and political relations with Africa. However, the new actors’ involvement in Africa has posed a challenge for the EU’s traditional economic and political interests in Africa. In response to the competition by these new actors, the EU has reinforced its security relations with Africa to keep up its economic and political interests on the African continent.

The Role of Global Actors in Africa

Global powers’ economic and political interests in Africa have influenced the EU’s foreign and security policy towards Africa. Their increasing roles in Africa have undermined the EU’s economic and political interests on the continent of Africa. In particular, the establishment of the United States Africa Command (USAFRICOM) in 2007 was a significant step in reinforcing the USA’s political and economic involvement in Africa. The role of the global actors, in particular the USA, Russia and Japan, has affected political and economic developments in Africa and in the world. These three countries have strong historical, economic, and political relations with the countries of Africa. Therefore, they play a vigorous role in reinforcing the African regional organisations and security fields. For example, the USA established “USAFRICOM or AFRICOM” in October 2007, with the aim of strengthening security cooperation between itself and Africa, and to address together new challenges and opportunities. The USAFRICOM’s main goal in Africa is to maintain the USA’s geo-economic and geo-strategic interests in Africa.18 Most importantly, the USA imports 22 percent of its oil from Africa, and it will reach up to 26 percent by 2015.19

Likewise, Russia has recently consolidated its political and economic relations with Africa. In June 2009, the Russian president, Dimity Medvedev, made an historic visit to Egypt, Nigeria, Namibia, and Angola, during which political and economic relations were strengthened. Particularly, Russia’s high technological power plays a significant role in relations with the African countries, in, for example, an important agreement with Angola the “Angolan National System of Satellite Communications and Broadcasting (ANGOSAT).” The most important Russian companies operating in Africa are Gazprom, Lukoil, Rusal, Sintez, Alrosa, Renkova, and Rosatom. In addition, Russia, as a permanent member of the UN Security Council, plays a pivotal role in the UN peacekeeping operations in Africa.

Japan, meanwhile, as a member of the G8 group also has solid ties with Africa. First, it keeps its political relations with the African states in order to get their support for a non-permanent membership of the UN Security Council. Second, it hosts the Africa-Japan Forum every five years and has opened new embassies in recent years in Africa, including Botswana and Mali. Organising an Africa-Japan Forum every five years and developing its political relations with Africa allows Japan to increase its global power in Africa. Third, it is greatly dependent on outside raw materials, including oil, gas, and metals, and sees Africa as a significant source.20

The new actors’ involvement in Africa has posed a challenge for the EU’s traditional economic and political interests. In response to the competition by these new actors, the EU has reinforced its security relations with Africa to keep up its economic and political interests on the African continent

The global actors have consolidated their political and economic relations with Africa. Despite the global economic crisis of 2008, the EU has continued to increase its international power in African politics, in particular in the fields of peace and security. It can be said that the EU has created new security policies towards Africa based on its own political and economic interests. For instance, the EU established the African Peace Facility (APF) in 2004 with the AU to foster security cooperation between the two continents. Importantly, the EU has deployed 10 peacekeeping operations in Africa since 2003 to maintain peace and security on the African continent. One of the most important aims of the APF is to sustain peace, security, and stability in Africa.

The Emergence of a New Political Climate in Africa

Since 1990, integration movements have increased among the African nations, and more importantly, democratic movements have spread over the continent. After 2000, many African states were transformed from an authoritarian system to multiparty system. In addition, the concepts of democracy, human rights, rule of law, civil society, and transparency have become popular in recent years in Africa. Significantly, the appearance of the new regional organisations in Africa, such as the AU and NEPAD, has brought hope to Africa that it can resolve its structural problems. The significance of the concept of ownership, solidarity, and regional integration has also increased under the new regional organisations in Africa.

With the birth of the AU and NEPAD, the African leaders have begun to play more dynamic roles in resolving their common threats and challenges and creating new opportunities. For instance, the AU deployed peacekeeping operations in Burundi in 2003, in Sudan in 2004, and in Somalia in 2005. Meanwhile, it has also reinforced its political relations with international organisations and global institutions and powers, such as with the United Nations (UN), the World Bank (WB), the USA and the EU. The new changing political climate in Africa has also influenced the global actors’ traditional foreign and security policies towards Africa.

The OAU’s transformation into the AU in 2002 provided the drive to changing security relations between Africa and the EU. The EU has especially strengthened the AU’s security capacity, such as the establishment of the African Peace Facility (APF) within the AU in 2004 and the reinforcement of the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA). Furthermore, the EU has also increased its diplomatic relations with the AU since 2002. According to the Council of the EU, the AU is the most important regional organisation in Africa, making it a strong regional organisation in Africa of great significance to the interests of both Africa and the EU. The security relations between the EU and the AU peaked during the Darfur conflict, with the EU mostly providing financial assistance and diplomatic support to the AU.

The EU has created new security policies towards Africa based on its own political and economic interests. For instance, the EU established the African Peace Facility (APF) in 2004 with the AU to foster security cooperation between the two continents

The 911 Terrorist Attacks on the United States

Countering international terrorism has been one of the most important matters for the international organisations and states since 2000. In particular, the 11 September 2001 attacks on the USA provided Bush and his corporate interests with an opportunity to heighten and capitalise on increased security concerns in the world. The terrorist attack was a significant moment for world history, changing some traditional security approaches of the global powers. New dimensions of the concept of security have appeared and international organisations have become vital to remove the roots of international terrorism. While poverty, injustice, inequality, and discrimination have incited terrorism, so has the concept of security come to include economic, social, political, environmental, diplomatic, psychological, and military dimensions.

The UN Security Council21 highlighted that without international cooperation, international terrorism could not be eliminated. At the same time, international organisations and global powers, including the UN, the EU, the AU, Japan, Canada, and the USA have increasingly paid more attention to conflicts and wars in Africa. They reported that local conflict and wars have created many security challenges and threats for world security, such as international terrorism, drug and human trafficking, political and economic instability, immigration, and poverty. These threats and challenges not only threaten Africa’s security but also international security. International terrorism is one of the most substantial complex global challenges of the new millennium, both unpredictable and incapable of being defeated by one country alone. Therefore, international cooperation appears necessary for international organisations and states wishing to combat it. In particular, working with weak states and organisations has become crucial, as undeveloped countries have the potential to create many security problems for themselves and for the world.

Fighting the new global threats and challenges has been one of the most important priories of the EU’s foreign and security policy towards Africa. In doing so, developing relations with African organisations in the areas of peace and security, including the AU and the ECOWAS, has been a strategic objective of the EU. New global threats and challenges have had a significant impact on the development of the EU’s foreign and security policy in Africa.

The security relations between the EU and the AU peaked during the Darfur conflict, with the EU mostly providing financial assistance and diplomatic support to the AU during the conflict in Sudan

Conclusion

Since the colonial period, Africa has played a strategic role in world politics, as the second largest continent comprising 55 countries with a collective population of over one billion. It provides raw materials for the former colonial powers and therefore plays an important role in their economic development. At the same time, it is one of the most significant continents in the world in terms of natural resources and strategic position. Europe has strong historical, economic, and political relations with Africa. Moreover, throughout the history of colonialism, the former European colonial powers have developed various economic and political relations. This article discussed how the EU’s commercial interests shaped its security policy towards Africa.

The emergence of the new actors in Africa has partially affected the EU’s foreign and security policy towards Africa, in particular its economic interests. For example, China is the fastest growing economy in the world, and has been making deep inroads into African markets, as well as reinforcing economic and political engagement in African countries and organisations. The other new actors have also strengthened their political and economic relations with Africa, as this article explored. This jeopardizes the interests of the EU on the African continent, with its deep historical and economic interests. Africa is a key trading partner for the EU. As an external factor, new global challenges damage the interests of the EU in Africa.

As an important global actor, the EU has deployed 10 peacekeeping operations in Africa since 2003. Four of them are still operating in Africa. These new peacekeeping policies in Africa have increased its global power in world politics. Especially, the EU peacekeeping operations on the African continent demonstrated that the EU remains an important strategic actor, despite the new emerging global actors in Africa. Fighting against international terrorism, immigration problems, and drug trafficking have become among the most important security concerns for EU members. The EU’s security policy towards Africa is driven by somewhat contradictory rationales, characterized by dependence on natural resources and trade with Africa on the one hand and a genuine interest to maintain peace and stability on the continent on the other.

Endnotes

* I would like to thank Prof. Dr. Madeleine O. Hosli and Assoc. Prof. Dr. Kivanc Ulusoy for their valuable comments and critics on this article.

- A. Siradag. Cooperation between the African Union (AU) and the European Union (EU) with regard to peacemaking and peacekeeping in Africa. MA dissertation. Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg (2009), p. 129-130

- AMIS II is known as a civilian as well as military operation of the EU.

- See the Official Journal of the European Union, twelfth annual report according to article 8 (2) of Council common position 2008/944/CFSP defining common rules governing control of exports of military technology and equipment (2011/C 9/01), January 13, 2011, C 9/1, pg. 160-162.

- Commission of the European Communities. EU Strategy for Africa: Towards a Euro-African pact to accelerate Africa’s development {SEC(2005)1255} Brussels, November 12, 2005 COM(2005) 489 final.

- See the detailed report for France’s economic relations with Africa published by EUROSTAT, Revival of EU 27 trade in goods with Africa, STAT/10/178, November 26, 2010.

- Ibid., pp. 1-2.

- See the detailed report for the UK’s economic relations with Africa published by EUROSTAT, Revival of EU 27 trade in goods with Africa, STAT/10/178, November 26, 2010.

- C. Ero. “A critical assessment of Britain’s Africa policy,” Conflict, Security & Development, Vol. 1, No. 2, p. 66.

- T. Cargill. Our common strategic interests: Africa’s role in the post-G8 world (London: Chatham House, Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2010), p. 33.

- Commission of the European Communities. Strategy for Africa: an EU regional political partnership for peace, security and development in the Horn of Africa. Brussels, October 20, 2006 COM(2006) 601 final, {SEC(2006)1307, p. 5.

- M. Cathelin. EU’s Africa Foreign Policy after Lisbon (Conference Report, Brussels, October 18, 2011, Chatham House), p. 5.

- C. Alden, C. & A.C. Alves. China and Africa’s natural resources: the challenges and implications for development and governance (Johannesburg: South African Institute of International Affairs, 2009), p. 3-4.

- http://www.gov.cn/english/official/2010-12/23/content_1771603_3.htm (Accessed October 23, 2011).

- K.J. Voll. Africa and India: from long-standing relations towards future challenges (Brussels: Foundation for European Progressive Studiesi 2010), p. 7.

- Trade Law Centre for Southern Africa (2010). The African trading relationship with Brazil. Stellenbosh: Trade Law Centre for Southern Africa (TRALAC), p. 1.

- Turkey-Africa Cooperation Summit. Solidarity and partnership for a common future, Istanbul, August 18-21, 2008, pp. 1-3.

- See, the report published by the EU, EU-Africa Summit Revival of EU 27 trade in goods with Africa in the first nine months of 2010, STAT/10/178, November 26, 2010, p. 3.

- L. Ploch. Africa Command: U.S. strategic interests and the role of the U.S. military in Africa (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service, 2010), p. 16.

- Cargill, ibid, p. 20.

- Cargill, ibid, p. 29.

- United Nations Security Council. Resolution 1373 (2001) adopted by the Security Council at its 4385th meeting, on September 28, 2001, S/RES/1373 (2001), p. 1.