Even though they are not the sole forms of organization in a democratic system, as the late French jurist Georges Bourdeau put long ago, political parties constitute the most effective bodies of people’s will. With these features, political parties prioritize the institutions envisioned by the Constitution; and modern democracies without political parties are unthinkable. In this respect, political parties both sustain democracy and owe their existence to democratic systems. For this reason, democratic systems are obligated to provide both a legal and a political ground necessary for political parties to represent people. On the other hand, political parties should not harm this base to which they owe their existence and should not see it as an instrument only to meet the demands of their partisans.

Parties should have a democratic mindset and a democratic behaviour so that they equip the actual system with the requirements of democracy – the rule of law in particular – as a must for the existence of a strong democracy. In this context, political parties, first and foremost, unite people to accede government and while doing so, they must resort to statutory and legitimate means. Such a feature of political parties, at the same time, encourages competition, i.e. elections.

For many political scientists, the relationship between political parties and an election system has been a key area of research in order to understand the type of democratic regime and the nature of political change in a country

It is a rule of thumb for political parties to join elections although some of them refuse to participate in elections, believing that to do so will legitimize regimes (as in the example of the Communist Party of Ireland), or simply believing that elections are not rewarding for long-term objectives. Hence, in order to legitimize the political parties’ which govern a country, elections are as equally indispensable for political mechanisms as political parties are for democracy. In fact, research on election systems have proven that which social, economic, political and cultural trends and demands dominate a society and require political representation, and which political leaders and administrators should be entrusted to put them into practice can be determined only by means of an election system. This is to the extent that, as some of the leading international institutions and research initiatives (e.g., Freedom House, POLITY IV) predicate the existence of political parties on the democratization level of a country’s political system, they also consider whether or not the competition among political parties is fair, just and periodic.

Accordingly, for many political scientists, the relationship between political parties and an election system has been a key area of research in order to understand the type of democratic regime and the nature of political change in a country. All the research in this area commonly refers to the existence of a cyclical relationship between the political party system and the type of political system. Namely, the type of an election system (say, proportional representation) may determine the type of the political party system (multi-party system) which in turn may determine the type of political system in a country. However, the opposite may also be the case: the survival of a certain type of political system may require a certain type of political party system, and that may be achieved by a certain type of an election system. This is the reasoning behind the cyclical relationship.

A large volume of empirical research has been conducted for a concrete clarification of the cyclical relationship between the types of election system, political party system and political system. For example, Amanda L. Hoffman1 examined two basic hypotheses and confirmed the existence of such relations based on the data she obtained. The first hypothesis states that the increase in the number of political parties in a country increases the level of democracy in that country. The second hypothesis states that the countries that use the system of proportional representation have a higher level of democracy compared to other countries that do not implement it. Similar results have been found by other experts, such as Arend Lijphart, Michael Parenti and Pippa Norris2.

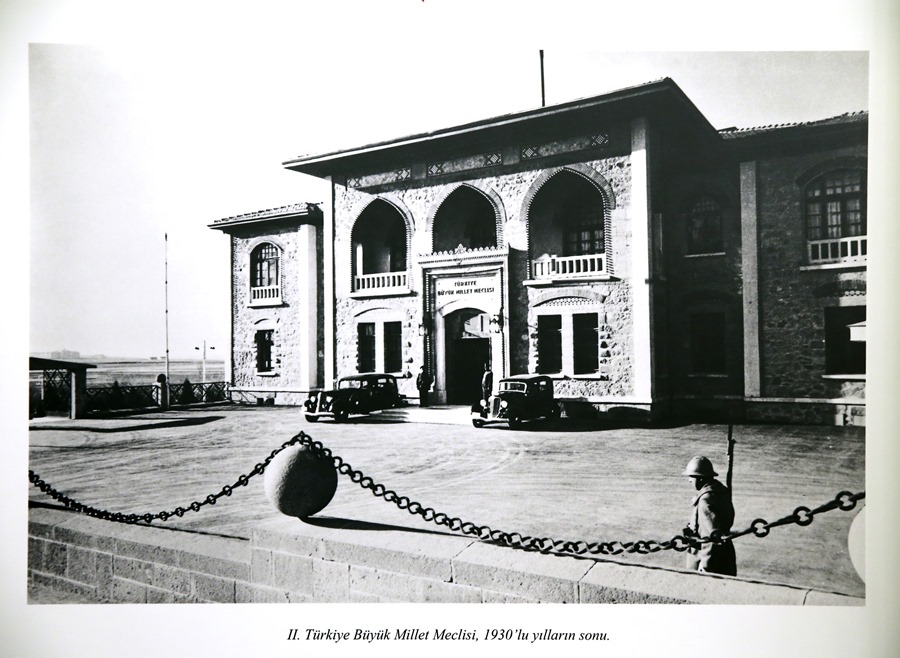

The second home of the Turkish Parliament in the 1930s. | AA PHOTO / RAŞİT AYDOĞAN

The abovementioned cyclical relationship also signals a critical feature for a democracy; that is political representation. In fact, as asserted by the above researchers in particular, the type of election system may also be exclusive rather than inclusive of the social segments in a society. For instance, the proportional representation system which has been implemented by many democracies today improves the legitimacy of a democratic system and enhances democratic standards by including mechanisms of equality, broader participation – that of women and minorities in particular – and a wide range of trends and demands.

The adoption and popularity of universal suffrage has led masses to obtain voting rights; thus, mass parties have joined in political competition despite having different organizational structures

On the other hand, the more apluralist political structure – as an end result of proportional representation – increases the inclusiveness of a democratic system, the more it will increase government instability; and that is a matter of objection. Albeit such an objection has some valid points that cannot be ruled out in some countries; empirical studies, similar to those conducted by Arend Lijphart,3 have proven that the objection is not strong enough to abandon ‘proportional representation’ in many democratic systems.

It has been consequently shown that extending the boundaries of pluralism through the type of election system in a democratic system is not the sole reason for political instability; and infact finding a balance between pluralism and political stability is a merit of mature democracies.

However, to ask the following is also appropriate: is it the factor of broader or narrower boundaries of pluralism (i.e. a comprehensive political representative) that causes instability in a democracy? For instance, Lijphart answers this question in favor of narrower boundaries of pluralism although the findings of studies on political representation and on rights of groups in general – minority rights in particular – differ.

As Florian Bieber4 puts some researchers regard impacts of election systems on political representation as a matter of different arrangements. For instance, some are against the participation of minorities, while others remain “formally” neutral. Some incline to support the competition of minority parties and ensure their participation yet others defend ethnical regionalism.

As purported by the different approaches above, the matter is that the representation of minorities is not the only factor which determines the stability of a democratic regime. Without doubt, stability in a democracy depends on many factors (level of economic development, political culture, etc.) apart from political representation.

The type of political system in a country may be deduced from the way in which minority (group) rights are brought into effect via political representation. In this respect, political scientists examine political systems in two categories: consociational and liberal. The raison d’étre of consociational democracy (for which the leading theorist and advocate is Lijpart) is to reduce the potential political tension that may stem from “lack of democracy”; in particular due to a proportional representation election system, and representation via reinforcement of some political mechanisms (minority veto, autonomy, bloc representation, etc.).

Accordingly, the goal here is to ensure the participation of minority groups in a political process, and consequently, forestall attempts to seek solutions to problems outside parliament. On the other hand, the “liberal” type, from the start, rejects political representation at the group level, and attaches importance to individual rights rather than group rights. In this regard, the “liberal” views political networking – minority based political networks in particular – as a destabilizing factor in a political process and system.

In consequence, the consociational type views broad representation of political groupings as a remedy for lesser democracy which would be caused by the further division of the societies that are already divided due to lack of democracy. The liberal type, on the other hand, claims the opposite: Rights and representation to be granted to political groupings will cause further splintering in already divided societies.

There are many necessary measures to fully implement political representation. Under any circumstances, however, the reduction of these measures to “political” remedies only means to ignore all other factors that cause lack of democracy, the most important of which is the volume of finance owned by those who demand representation. For this reason, without being cognizant of the political economy of parties, we can only see certain dimensions of the lack of democracy, where the parties are the leading actors of elections, the mechanisms materializing representation.

Notwithstanding, some scientists have emphasized that public financing of politics has as many disadvantages as it has benefits. Relevant researches have pointed out that the desire to maintain the advantageous position provided by public finance appears to be a factor preventing the participation of new parties in a political system. On the other hand, the distribution of public finance or state incentives depending on the election success (the percentage of gained votes and number of seats) detracts political parties from their objectives set in party programs and ideological values, and transforms them into catch-all machines, which only aim to gain the highest number of votes5. As a consequence, type-wise Cartel Parties dominate politics6.

As they took the political stage in the western world from the 19th century to the 1950s, political parties were not subject to any legal regulation. However, in the course of the period leading up to World War II, political parties were included in a constitutional framework so as to intercept the re-rise of the single-party dictatorships in Italy and Germany and of fascism. In fact, political parties in Italy (1947) and in Germany (1949) were included within constitutional frames; therefore, they no longer posed a despotic threat to democratic regimes.

Paving the way for constitutional regulation has also introduced the need for legal regulation of financial sources (incomes and expenditures) of parties. Such regulation was introduced in the 1970s. In that period, “financing politics” came under the spotlight due to monetary corruptions and scandals in the political systems of some western countries, including Britain, France, Germany, the U.S. and Japan, and that necessitated legal/constitutional regulations.

That political parties adopt economic aspects in the competition to accede government and view themselves as an economic entity, their voters as customers and the votes they gain as profit; therefore, they reduce masses to consumers to whom they market a “political good”

Without doubt, legal/constitutional regulations in question are not for disciplining parties but providing equality in a political process and a competition, and saving parties from the effects of external financial/monetary factors; therefore, helping them gain autonomy through financial support to be provided by the state/public (On this subject, a study report by Ingridvan Biezen is an eye-opener.)7

Party Typologies and Systems

The first and widely accepted classification in party typologies is with regard to their cadre and mass, introduced by the late Maurice Duverger. Cadre parties, in fact, do not require much effort; their functions are limited to election periods, they are led by a small group of people (influential in election circles), and they do not strive to gain new members. Cadre parties are old-fashioned parties, the foundations of which were laid in parliaments before the principle of universal suffrage was carried into effect.

The adoption and popularity of universal suffrage has led masses to obtain voting rights; thus, mass parties have joined in political competition despite having different organizational structures. Another reason for the emergence of mass parties is that difficulties in financing politics can only be overcome if broader social segments join forces.

However, the number of members is important for mass parties not only for financial concerns, but also for ideology and political belief. Even though, mass parties with these characteristics are a political phenomenon of the 20thcentury, we see different versions of them today, the most dominant typology of which is movement party: the emergence of a political party is based on a movement (national movement, Islamic movement, revolutionary movement, feminist movement, greens, etc.).8 Nevertheless, mass parties have today evolved into a range of types.

Considering a pluralist political system as dangerous, the leaders of the September 12, 1980 coup closed all political parties and banned their chairmen from politics. | AA PHOTO

A significant fact nowadays is that political parties adopt economic aspects in the competition to accede government and view themselves as an economic entity, their voters as customers and the votes they gain as profit; therefore, they reduce masses to consumers to whom they market a “political good” (party’s view and project, etc.). By doing so, political parties, in the end, have affected the formation of three types of parties: catch-all party, business-firm party and cartel party.

Catch-all parties are not strict or strong in terms of organizational structure and ideology, but are governed by a strong leadership. Since the goal is to appeal to various interest groups and segments, they aim to appeal to all voters9. As for the business-firm parties, the leader of the party is, at the same time, the owner of a business firm, and his/her political influence comes from a social network provided by the company. The goal here is to appeal to voters by transforming the leader into almost a pop-culture icon and use the leader’s personal appeal, such as youth, good looks and education level, etc. So much so that, in order to win the highest number of votes, a business-firm party is directed by a talented technical team from outside rather than a group of political volunteers.10

The characteristic of a cartel party appears somewhat different though it is based on the same mentality as the others. The “cartel,” in fact, is a concept in the field of economy and means an implicit or explicit agreement between a collection of otherwise independent businesses that act together as if they were a single producer and thus reduce competition or in a sense, completely end competition.

If such mentality guiding economic activities makes an agreement necessary among predominant parties in political activities, cartel type comes into play. The cartel party type implies a de facto political coalition amongst those parties sharing a common interest. As a matter of fact, behind such a coalition there lies the motive to protect and consolidate vested rights, positions and privilages of the existing parties in the system. In a sense, the cartel type suggests that political patronage is the goal of politics; therefore, symbolizing the intensity of the battle of sharing amongst parties.11

Under the influence of Duverger, numeric criterion had been used for a long time in order to categorize party systems determined by party typologies. Such numeric criterion uses the number of parties in a system and classifies parties in three groups: Single-party, two-party and multi-party systems. Imperfections in Duverger’s classification of political parties (for instance, his suggesting excessively broad and, therefore, meaningless categories containing quite different types such as single-party system) have led to criticisms among some authors that numeric criterion is insufficient. In regards to the typology of party systems today, the most in-depth analytical frame has been developed by the Italian political scientist Giovanni Sartori.12 Quite different from the classical categorization, Sartori identifies seven classes of a party system: one-party system, hegemonic party system, predominant party system, two-party system, limited pluralist party system, extreme pluralist party system, and atomized party system.

Sartori, first of all, makes a distinction at the level of political systems and divides them into competitive and non-competitive. Accordingly, competitive systems have two sub-categories: polarized pluralism and moderate pluralism. The two-party system and predominant party system are the examples of moderate pluralism. Non-competitive systems, on the other hand, contain single-party and hegemonic party systems. Sub-categories of these are: totalitarian single-party, authoritarian single-party, pragmatic single-party and ideological-hegemonic, pragmatic hegemonic party system. Sartori’s typology allows the formation of a conceptual background about party systems. It is appropriate to explain, in a limited fashion, such typology. Sartori, for instance, makes a distinction between type and operation when it comes to a two-party system. Therefore, while we discuss the two-party system in a country, we may either mean that there are two types of parties in that country or that the operation of the party system in that country resembles the operation of a two-party system. However, the impact of third parties should be considered here. Although Sartori seems to accept “three-party system” as a category, he refuses classifications by some authors such as a “two-and-a-half party” system. For Sartori, it will be necessary to talk about a two-party system if a third party, as in Britain, does not affect the operation of a two-party system. The existence of a two-party system depends on the following conditions: (i) The competition for the majority of parliamentary seats must remain between two parties, (ii) One of the competing parties should be deemed successful, (iii) The party winning the majority should form the government, (iv) Rotation should be possible between the governing and opposition parties.

From the point of the above given conditions, Britain, the United States of America, the New Zealand, Austria and Canada take the lead in the implementation of a two-party system. The majority can be won by a slightest difference, or the difference of vote share may be dramatic. If the latter is the case, one of the parties will be able to remain in government for a long time and the possibility of rotation between a government and an opposition will be less likely. If the difference of vote share between two parties is huge, the stronger one will continue to remain in government. In this case, it would be appropriate to examine the Predominant Party system.

National Security Council closed all political parties of the pre-September 12, 1980 coup and banned their chairmen from politics. Three years later, only three “ratified” parties were allowed to join the general election in 1983. The reason was the existence of too many political parties in the pre-September 12 period and perhaps as a result of this, an “extreme pluralist political system” was deemed “dangerous”

According to Sartori, a predominant party system is one where one of the parties in a multi-party system dominates legal and legitimate others and they are the independent rivals of the dominating party. Rotation is out of question for acceding government. Same parties uninterruptedly win elections and have the absolute majority in parliament. The author categorizes countries with a predominant party system according to the dominance period of a predominant party, and includes Turkey in this category (1950-1960; 1965-1973 periods) (without doubt, we should add to this the AK Party government periods from 2002 till today).

Nonetheless, although Sartori includes the hegemonic party system in non-competitive category, one should pay attention to the characteristic of a hegemonic party that, in a way, is reminiscent of a predominant party system. The political reality in a hegemonic party system is that only one party is provided with the opportunity (either nominally or de facto) to govern a country, others are not. In other words, neither a real inter-party competition nor change of power really exists (due to ideological and pragmatic reasons) despite the existence of many parties. This is important at least in terms that a predominant party system may transform into a hegemonic type at a certain conjuncture.

With the restriction on the number of political parties and the 10 percent election threshold, the MGK designed an authoritarian party system by means of electoral engineering

The last category in Sartori’s classification is atomized pluralism. With this, Sartori refers to party systems in Asian and particularly African countries where extremist and polarized pluralism in general exists in a given period of time. Parties in these countries usually oscillate between one-party and multi-party systems. Although Asian and African societies, which have many yet uncrystalized parties, proceed from a one-party system to an extreme pluralist system; they later return to a one-party system from an extreme pluralist system due to the lack of a well developed concept of institutionalization.

Situation in Turkey

The 2nd clause of Article 68 in the 1982 Constitution stipulates: “Political parties are indispensable elements of democratic political life,” and the 1st clause reads: “Citizens have the right to form political parties and duly join and withdraw from them…” As the Constitution states, “Political parties shall be formed without prior permission, and shall pursue their activities in accordance with the provisions set forth in the Constitution and laws.” The 3rd clause of Article 68 implies that political parties shall be subject to a legal framework. The same constitution, however, through some restrictions (in Article 68/4th clause)13 implies that the nature of “political parties being indispensable elements of democratic political life” is not absolute. More correctly, the Constitution allows interpretation of the aforementioned “absoluteness” only to mean that the existence of political parties must dwell on insuring the existence of democracy.

In fact, the 1st paragraph of Article 69 states such an interpretation in a more concrete way: “The activities, internal regulations and operation of political parties shall be in line with democratic principles. The application of these principles is regulated by law.” The provision has been crystalized by the law number 2820, put into force in 1983. Principally, it would be appropriate to shed light on the definition of ‘Party’ and its content as suggested by the Political Parties Law (PPL). This is necessary to be able to understand why political parties and the election system need reforms, and the deficiencies encountered in their operations.

Article 3 in the PPL describes a political party as follows: Political parties in compliance with the Constitution and laws, help the formation of the national will through their overt propaganda and efforts in the direction of party views cited in party programs and bylaws – via local administration and representative elections. Political parties are legal entities that are organized to have countrywide activities and pursue the goal of carrying the country to the level of contemporary civilization within a democratic state and social order.

The provisions stated in the PPL with regards to the description and functions of political parties are the key factors behind the problems that originate from practices of parties and the party system. In fact, research and reviews of leading political scientists in Turkey have clearly exposed the situation. For instance, Professor Ergun Özbudun in his review pays attention to non-system interventions in party structures and changes in party systems; with the military intervention on September 12, 1980 as an extreme example of such a non-system intervention.14

It is useful to recall that the National Security Council (MGK) closed all political parties of the pre-September 12, 1980 coup and banned their chairmen from politics. Three years later, only three “ratified” parties were allowed to join the general election in 1983. The reason was the existence of too many political parties in the pre-September 12 period and perhaps as a result of this, an “extreme pluralist political system” was deemed “dangerous.” To this end, Professor Sabri Sayarı15 in his research brought to attention the leading role of an invisible historical factor in the deeper background: State elites’ motives to design party politics.

Indeed, state elites acted on such motives, an “extreme” example of which was to bring a MGK regime into action. With the restriction on the number of political parties and the 10 percent election threshold, the MGK designed an authoritarian party system by means of electoral engineering. Notwithstanding, as Özbudun points out, a political party shaped by the will of the MGK officials (a two-party or a two-and-a-half party system) did not live long.16In fact, the effective number of parties in the period of 1983-1999 (as of the 1995 elections in particular) and the degree of fragmentation increased, such that between 1995 and 2002 the increase exceeded that of the 1961-1980 period. The number of political parties that should be “factored in” reached seven in the period of 1995-2002.

One of the most critical outcomes of the 2002 election was that center-right parties, as the predominant parties of Turkish politics since 1950, entered a period of fatigue and their votes largely shifted to the AK Party

In line with these developments, Professor Özbudun stated that the rise of the Justice and Development Party (AK Party) in the 2002 election became a turning point and the beginning of radical changes. He further said: “…As a consequence of the 10 percent election threshold, only two parties managed to win parliamentary seats and that helped the AK Party to win the parliamentary majority by gaining two thirds of the total seats (66 percent), the CHP, for the same reason, obtained a substantial over-presentation (32.4 percent). The effective number of parties radically dropped to one and half. One of the most critical outcomes of the 2002 election was that center-right parties, as the predominant parties of Turkish politics since 1950, entered a period of fatigue and their votes largely shifted to the AK Party. The weakening period of the old center-right parties seemed to come to an end in the 2007 and 2011 elections.”

The 10 percent election threshold lowered the effective number of parties to 1.2. With this, the party system in Turkey has entertained a trend of increasing stability, and that was clearly seen in the June 12, 2011 general election. This threshold percentage has subsequently become an important topic of discussion. Those who are involved in the discussion are divided into two groups. One argues that the election threshold will, in fact, restrict the effective number of parties and bring stability into governing while the other group asserts that the 10 percent election threshold will cause under-representation; therefore, harming the pluralism norm of democracy.

Suffice it to say that if “representation” means a change in the percentage of total votes parties win from one election to the other, then technically some political scientists stress that there was no problem with the 2011 election in which the 10 percent election threshold was implemented. For instance, the same four parties which partook in the 2007 elections (AK Party, CHP, MHP, BDP/Independents) joined the 2011 elections. The total percentage of the vote that they gained in the 2007 elections was 87 percent and it rose to 95.5 percent in 2011. According to Özbudun, “It may be interpreted that a four-party system has settled in Turkey and that such a system has added the Grand National Assembly of Turkey’s power of representation compared to the previous period.”

On the other hand, Professor Sayarı in his research published in 2007 states that the fragmented Turkish party system, between 1991 and 2002, began to evolve into a predominant party system with the AK Party’s coming to power in 2002. Indeed, the AK Party did not only win elections consecutively but also gradually increased its votes. These elections prove that Turkey has a predominant party system.

The most important and well accepted corollary of the predominant party system, steered by the AK Party, is political stability. As Sayarı proved in his research, a total of 14 governments were formed from 1983 up until the AK Party acceded the government in November 2002, six of which were one-party governments while the others were coalition governments. The AK Party has been in power since November 2002, in accordance with the D’hondt election system with the 10 percent election threshold and continues to maintain its one-party Government.

The AK Party has been the victim of the political culture of the tutelage which implemented banning of political parties as a guarantee for stability. So, the AK Party has broadened the boundaries of the democratic political system through the Constitutional Referendum in 2011 and through relevant constitutional amendments. The amendments in the Constitution have provided leverage to the AK Party to put a distance between itself and the understanding of the past that “closing parties” would bring stability.

In fact, political parties are exposed to legal/constitutional regulations with the expectation of a universal guarantee being granted in respect of their functions within a democratic system. In other words, legal regulations regarding political parties are considered as a whole set of norms that denote how they will play the game of democratic politics. As the norms, of founding a political party, are set in advance, to know in advance the norms under which a political party would be closed and by which (constitutional) organs, upon their violation, is an expression of the guarantee to prevent political arbitrariness and assure a fair game of politics. Such an understanding is a universal norm in a constitutional state.

At first sight, in line with the above understanding, the decision-making authority to close political parties in Turkey rests with the Constitutional Court, not general courts. In the 1982 Constitution, this authority is stated, in the 5thclause of Article 69, as: “The final judgment for the closure of political parties rests with the Constitutional Court after the Office of Chief Procecutor of the Republic files a suit.” However, considering that the total number of parties closed by the Court to-date is 24, it is doubtful whether legal/constitutional regulations in Turkey provide any “political guarantee” to political parties.

When we consider other countries, we also see impositions for party closures by means of legal/constitutional regulations on political parties, such as17 in Germany, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, India, the Netherlands, Britain, Spain, Sweden, Italy, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland, Portugal, Romania, and Slovakia.

Legal regulations on political parties differ in some of the aforementioned countries. In some countries, parties are regarded as associations functioning in the framework of the Constitution without any other politically specific constitutional provisions. No special legal regulation, such as a “political parties law” exists in other countries; and for instance, parties are addressed under civil code provisions. Organs with the authority to close down parties also differ. The authority to close down parties can rest with either the Constitutional Court, the Government, the Chief Prosecutor the Supreme Court of Appeal or the High Administrative Court.

The reasons to close political parties also differ from one country to another. In Germany and Italy, for instance, Nazism/Fascism and Communism, as a party or trend, with a possible threat of establishing totalitarian regimes, constitutes reason for closing or banning political parties, due to political traumas caused by Nazi and Fascist ideologies in the run up to World War II. As a matter of fact, the Nazi Party in 1949, the German Socialist State Party (Sozialistische Reichspartei Deutschlands) in 1952; and the German Communist Party (Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands) in 1956 were closed by the Constitutional Court. Founded by Mussolini in 1943, the National Fascist Party (Partito Nazionale Fascista) was closed by the Government in Italy. Political parties have been closed for “racism and xenophobia” in Belgium and “separatism” in Spain. For instance, the Batasuna Party (a political proxy of ETA) was closed in 2003 for this reason. A total of 24 parties have been closed in Turkey to date, 11 of which were for “separatism,” four for “anti-laicism” and nine for “imperfect practice of legal formalities.”18

The AK Party has been the victim of the political culture of the tutelage which implemented banning of political parties as a guarantee for stability. So, the AK Party has broadened the boundaries of the democratic political system through the Constitutional Referendum in 2011 and through relevant constitutional amendments

Although they vary, guidelines on dissolution of political parties have been set by the European Commission for Democracy Through Law also known as the Venice Commission, composed of independent jurists, and founded in 1990 by the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe. The Commission conducts research and publishes results on “constitutional status” and “party closing” for member countries, including Turkey. The Commission released its first report, based on a survey, entitled “The Report on Prohibition of Political Parties and Analogous Measures” in 1998. Following this report, the Venice Commission prepared “Guidelines for Prohibition and Dissolution of Political Parties and Analogous Measures” in 1999, and submitted to the Parliamentarians Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) and the Office of Secretary General. The Venice Commission dwells upon the reinforcement of the relation between political parties and democracy.

Conclusion

The word “party” means “piece” in Turkish; and it only becomes perfectly functional if a crystal-clear description of ‘which Whole’ the “piece” belongs to is thoroughly elaborated. The ‘Whole’ composed of its pieces –called political parties– is the ‘Democratic Political System.’ This being the case, a dialectic relation exists among political parties and the political system they function in: the more democratic a political system is, the more democratically political parties will have to function. On the other hand, the higher the eagerness of political parties to function democratically, the more the democratic capacity of a political system will expand.

Endnotes

- Amanda Hoffman, “Political Parties, Electoral Systems and Democracy: A Cross-national Analysis,” European Journal of Political Research, No. 44 (2005).

- Hoffman, “Political Parties, Electoral Systems and Democracy: A Cross-national Analysis.”

- Arend Lijphart, Demokrasi Motifleri, translated by Güneş Ayas and Utku Umut Bulsun, (İstanbul: Salyangoz Yayınları, 2006).

- Florian Bieber, “Seçim Sistemleri ve Orta ve Güneydoğu Avrupa’da Azınlık Partileri,” in Ersin Erkan (ed.), Seçim Sistemleri ve Etnik Azınlıkların Parlamenter Temsili, (İstanbul: BETA Basım, 2010).

- Jonathan Hopkin, “The Problem with Party Finance,” Party Politics, Vol. 10, No. 6 (2004).

- Mark Blyth and Randy Katz, “From Carch-all Politics to Cartelisation: The Political Economy of the Cartel Party,” West European Politics, Vol. 28, No. 1 (2005); Klaus Detterbek, “Party Cartel and Cartel Parties in Germany,” German Politics, Vol. 17, No. 1 (March, 2008).

- Ingrid van Biezen, “Financing Political Parties and Election Campaigns-Guideline,” Council of European Publishing, (December, 2003).

- Ayşen Uysal and Oğuz Topak, Particiler, (İstanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2010).

- Otto Kircheimer, “The Transformation of the Western European Party Systems,” in Joseph La Palombara and Myron Weiner (eds.), Political Parties and Political Development, (New York: West European Politics, 1969).

- Jonathan Hopkin and Caterina Paolucci, “The Business Firm Model of Party Organization: Cases from Spain and Italy,” European Journal of Political Research, No. 35 (1999).

- Petr Kopecky et al., “Beyond the Cartel Party? Party Patronage and the Nature of Parties in New Democracies,” IPSA/ECPR Conference, (Sao Paulo: February, 2011), pp. 16-19.

- Giovanni Sartori, Political Parties and Party Systems, (New York: ECPR Press, 1976).

- Article 68/4 states: “The statutes and programs, as well as the activities of political parties shall not be contrary to the independence of the State, its indivisible integrity with its territory and nation, human rights, the principles of equality and the rule of law, sovereignty of the nation, the principles of the democratic and secular republic; they shall not aim to promote or establish class or group dictatorship or dictatorship of any kind, nor shall they incite citizens to crime.”

- Ergun Özbudun, Türkiye’de Parti ve Seçim Sistemi (İstanbul: İstangul Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları, 2011).

- Sabri Sayarı, “Non-Electoral Sources of Party System Change in Turkey”, in Prof. Dr. Ergun Özbudun’a Armağan, Vol. 1 (Ankara: 2008).

- Özbudun, Türkiye’de Parti ve Seçim Sistemi.

- Beyhan Kaptıkaçtı, et al., “Siyasi Partilerin Kapatılması Konusunda Türkiye ve Bazı Ülkelerdeki Yasal Düzenlemeler,” Turkish Grand National Assembly (TGNA) Research Center, (March, 2008).

- Kaptıkaçtı, “Siyasi Partilerin Kapatılması Konusunda Türkiye ve Bazı Ülkelerdeki Yasal Düzenlemeler.”