Introduction

“If ‘Darwin prizes’ were to be given to the countries that have best responded to challenging times, Brazil would be the runaway first-prize winner, with possibly Turkey in second place.”2 This statement from The Globalist expressed a widespread perception of the two countries in the period following their joint initiative to broker a nuclear deal with Iran in 2010. While the deal was rebuffed by the permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, and thus never came to be implemented, the initiative of the two “emerging powers” received global attention by political leaders and the media. The joint activism of two countries with traditionally weak economic and political ties, on a global security issue, suggested that the rapid economic growth and social development of middle powers in the early 20th century had implications beyond the economic and trade sphere. The so-called “emerging” powers were seen to be developing shared agendas on global issues, and to be claiming a greater share and a greater voice in issues of global relevance and global governance. More interestingly, the partnership between Brazil and Turkey posed the question whether these “emerging powers” were developing common identities and interests, which could bring former “strangers” on the international scene closer in pursuit of joint goals.

The questions raised by the cooperation between these two emerging powers are inextricably linked to the realization of a rapid transformation of the global order in the 21st century. From multipolar to interpolar and apolar, from post-hegemonic to post-American and to no one’s post-western world, uncertainty about the state of the new global order and the dynamics that govern it permeate academic literature and policy inquiries.3 In this new world order “picking allies, making friends and containing adversaries […] promises to be an unclear, ambiguous and delicate process.”4 With this in mind, and having observed the growing and deepening relations between Turkey and Brazil, whose position in the transforming global order has earned them the titles of “emerging” or “regional” powers, this article will attempt to discern the idea-driven and interest-driven motivations behind the construction of their ties. In doing so, it will aim to produce wider hypotheses about the nature of partnerships and alliances in a system characterized by multipolarity.

The article begins by examining basic assumptions about the “era of multipolarity.” It then offers an overview the fundamental explanations for ally and partner choice according to interest-based realist theory and idea-based constructivist approaches. Following these two theoretical sections, the article provides a historical account of Turkey-Brazil relations in the past decade (2002-2012) with a focus on the years of intense approximation (2010-2012). The final section uses these empirical observations in order to draw conclusions regarding the motivations behind the Brazil-Turkey partnership, on the basis of idea- and interest-based approaches.

Shifting Power: On the Emergence of the Multipolar World

This article will take in consideration two different paradigms: (a) the shift in the configuration of state power in the international system and (b) the –arguably- waning American influence, or post-Americanism. In the majority of the literature, these two processes are often viewed as interrelated and similar.5 Reflection on the future state of the global order began with the end of the Cold War, but gained renewed force with the commodities boom of the 21st century, particularly after the 2008 economic crisis. The crisis, which hit established powers, severely damaging part of their economies, opened space for resource-rich economies with rapid growth to claim more power, more representation and more weight in international affairs. This led emerging powers with economic, political and normative aspirations, such as Brazil and Turkey, to engage in more proactive behavior within the structures of the international system, and to advocate for reforms in the management of global governance.

There is a general consensus that, up until World War I, the dominant model in the international system was that of a multipolar world dominated by tensions amongst the European nations. This period was followed by the rise of the USA, soon to be counterbalanced by the USSR. This led to the bipolar order that characterized the Cold War and largely dominated the second half of the 20th century. With the end of the Cold War, the literature by and large acknowledged the advent of a “unipolar moment.”6

The diffusion of power and the lack of established leadership in the nonpolar system pushes states towards the adoption of diversified external relations, including the creation of alliances and partnerships with a diverse group of “others.”

The end of unipolarity is still an ongoing debate among scholars. While most literature points to increasing globalization in the late 1990s and 2000s as an indication of a diffusion of power, this diffusion is discussed and viewed in diverging ways. Giovanni Grevi of the European Council on Foreign Relations advocates a new form of multipolarity that is infused with the increasing interdependence of the cyber-age. States must rely on each other more than ever in order to attain economic growth, a fundamental form of power in what is coined as an era of “geoeconomics.” This interdependence is perceived as an incentive for continuous –and continuously evolving– relations: for these reasons, Grevi argues that this is the era of “interpolarity.”7 Richard Haass on the other hand, argues that the new multipolarity stems from a move beyond exclusively state-based power politics.8 According to this view, in the contemporary international system, the “G-zero” world, multiple actors possess power and, consequently, there is no space for effective or consistent leadership.9 This over-diffusion of power has led to a system where no single entity has enough influence to control the system -nonpolarity. Indeed, something both Haas and Grevi seem to agree upon is that power (economic or military) and influence are no longer directly correlated.

For emerging countries, both scenarios lead to a world with a greater diffusion of power and a greater level of interdependence, where alliances are created to benefit strategic interests. This has translated into non-traditional partnerships with states and actors besides the U.S., to create checks on waning U.S. power. Uncertainty in an interpolar system has led to an increase in strategic alliances amongst states. In a nonpolar system, alliances are made up of coalitions of state and non-state actors.

Then Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu welcomes then Brazilian Defense Minister Celso Amorim prior to a meeting in Ankara, on August 21, 2013. | AFP PHOTO / ADEM ALTAN

Then Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu welcomes then Brazilian Defense Minister Celso Amorim prior to a meeting in Ankara, on August 21, 2013. | AFP PHOTO / ADEM ALTAN

In his own approach to this debate, Fareed Zakaria also acknowledges the aforementioned shift, but defines American unipolarism much more broadly, beginning at the end of World War I; he thus brands the future system as post-American. Zakaria argues that a number of the here-to-fore relative advantages of the U.S., for example technology, have diffused across the international system due to globalization, while the U.S. becomes increasingly less able to adapt.10 This has led to the “rise of the rest,” a shift in the global order from a hegemonic American system to a post-American system where other countries begin to catch up with the U.S. and new global powers (such as the BRICS) emerge. These powers, in turn, in the manner of rising hegemons before them, witness a continuous increase of their influence and of their capability to exert their interests on the international stage.

Scholarly work and popular media alike have tended to refer to the new rising players as “emerging powers.” However, a consensus has yet to be reached regarding the exact definition of the term. One aspect of these powers is that they are often more influential in their region, thus often attracting the characterization “regional powers,” a term indicating a country’s ability to play a stabilizing role in its own region; willingness to assume such a role; and acceptance by its neighbors as a leader responsible for regional security.11 The ability to exercise power resources regionally differentiates emerging regional powers from “middle” powers. Elsewhere in the literature, the definition of emerging (or rising) powers is less linked to leadership as a security provider and is used more generally as recognition of the rising influence of several countries that have increased their presence in global affairs. One additional aspect attributed to emerging powers is the articulation of a desire for leadership in global governance.12 The term is commonly used to refer to the G20 member countries, thus drawing a direct correlation between GDP and power. It follows, then, that the dividing lines between the terms “emerging,” “middle,” and “regional” powers are often unclear and that the terms are often used interchangeably or in a complimentary manner to indicate a more nuanced understanding of the nature of the country in question, the degree of its regional or global aspirations, its economic affluence and its power resources.

Explaining Alliances and Partnerships in a Multipolar World

The new global order and the end of unipolarity have been discussed at length since the end of the Cold War with varying conclusions during the 1990s. Increasingly after the mid-2000s, the literature concedes to a substantial reduction of the so-called “U.S. hegemony,” with substantial uncertainty about the future of a world without a dominant power. Uncertainty has a negative influence on relationships because it inhibits the creation of trust over iterated interactions. With uncertainty dominant in the system, and the subsequently emerging lack of trust, the need for contractual relations and established institutions becomes necessary in order to create checks or reaffirm commitments as traditional trust-building mechanisms cannot be used. At the same time, the diffusion of power and the lack of established leadership in the nonpolar system pushes states towards the adoption of diversified external relations, including the creation of alliances and partnerships with a diverse group of “others.”

Lai and Reiter define alliance as a voluntary agreement between states in which the signatories promise to take action (such as military intervention) under specific circumstances.13 Summarizing the existing literature on interstate cooperation, the authors argue that these alliances are usually explained according to three major theories: the first one argues that alliances may stem from credible commitments14 and highlights that democracies are more likely to make credible commitments than authoritarian regimes; a constructivist approach would suggest that the basic collective action problems that impede international cooperation can be overcome if actors move away from self-oriented interest, toward a collective oriented conception of interest.15 Another strain of explanations emphasizes the importance of economic interdependence.16

The decision to ally, and the choice of partners, is arguably affected by the exogenous variable which is the international order. As Serfaty (2011) posits, “in a unipolar world, allies are known (and sought) for their willingness, and adversaries are recognized (and defeated) for their capabilities; there is little need for diplomacy, and consensus is asserted rather than negotiated. By comparison, the emerging world order now depends on a geopolitical cartography that is fraught with perplexities and contradictions.”17 With regard to minor powers in particular, Krause & Singer (2001) argue that, given their limited capabilities, multipolarity offers more choice. Unlike during the Cold War, smaller states may now choose to involve themselves on an ad hoc basis in a wide range of security and other commitments.18

The question thus ensues: how and why do states choose and make allies and partners in this uncertain world? Different approaches in International Relations can provide us with distinct insights on this question. Here, we analyze two of them: realism (as interest-based) and constructivism (as ideas-based).

According to realists, and specifically neo-realists, the international system is an anarchical one. States are seen as unitary actors driven by national interests.19 In this hostile scenario, the answer to why states decide to make alliances lies in the feature that stands out most prominently in states’ behavior: interest. Hans Morgenthau argued that members of alliances have common interests based on the fear of other states, while for Stephen Walt, alliances stem from a balance of threat.

Since the world is competitive and material resources scarce, cooperation is unlikely. Under the security dilemma,20 cooperation becomes possible if the gains resulting from this alliance are augmented. Mechanisms such as treaties and law might increase confidence between actors and lead them to cooperation because they make surveillance and monitoring possible.

Thus States may create international law and international institutions, and may enforce the rules they codify. However, it is not the rules themselves that determine why a State acts a particular way, but instead the underlying material interests and power relations. International law is thus a symptom of State behavior, not a cause.21

Power, according to Waltz, is a reflection of a State’s capabilities. If that State is to change the global order, it needs to become a pole in the international structure. In order to become a pole, such State must seek to increase its capabilities, and alliances provide one way of doing so.

From a realist perspective, the relative anarchy of the emerging multi-, inter- or non-polarity entails that a state must rely upon itself for survival; therefore, alliances will only be made where there is mutual self-benefit for both parties involved. The mechanism that ensures trust in this realist form of the relationship is the national interest that is fulfilled by the alliance.

From a constructivist point of view, the response of the state to uncertainty is entirely dependent upon the identity of the state, which includes its conception of “security” and its culture. The decision to create partnerships, alliances or coalitions can be interpreted through the existence or absence of shared meanings, understandings and normative interpretations of the world and the environment between two or more states. As Slaughter writes, referring to constructivists: “These arguments fit under the institutionalist rubric of explaining international co-operation, but based on constructed attitudes rather than the rational pursuit of objective interests.”

The two countries share similar values, principles, aspirations and expectations for a better future in their respective regions and in a world which is undergoing a rapid transformation

As one of the major fathers of constructivism, Alexander Wendt has opened the possibility of thinking of anarchy as having multiple meanings for different actors, based on their own communities of intersubjective understandings and practices. If, then, multiple understandings are possible, constructivism upholds that cooperation is possible under anarchy but that it relies on the understanding of state interests within a particular issue area. “The distribution of identities and interests of the relevant states would then help account for whether cooperation is possible.”22 Cooperation and partnership are largely dependent on the perception of interest, of the issue area and of the identity of the other state. “Sitting down to negotiate a trade agreement among friends (as opposed to adversaries or unknowns) affects a state’s willingness to lead with a cooperative move. Perhaps it would no longer understand its interests as the unilateral exploitation of the other state. Instead it might see itself as a partner in pursuit of some value other than narrow strategic interest.”23

Building on these theories and on Serfaty’s argument that the nature of alliances has undergone a transformation along with that of the global order, the task at hand is to understand how emerging powers –a product of the new global order– engage in the practice of alliance formation, broadly defined to include partnerships, cooperation and bandwagoning. This challenge follows the thinking of Andrew Hurrell who, as early as 2006, criticized neorealist approaches as being written from the perspective of the United States, failing to define what they mean by “bandwagoning” or to explain what determines the choice among the different forms that the alignment with the hegemon might take.24

With regard specifically as to why emerging powers might be compelled to form coalitions, Hurrell puts a strong emphasis on the role of international institutions. These can constrain the powerful through established rules and procedures, and they provide weaker states with political space to build coalitions in order to try to affect emerging norms in ways that are congruent with their interests. Furthermore, international institutions provide weaker states with “voice opportunities” to make known their interests and to bid for political support in the broader marketplace of ideas.

A number of concrete initiatives between the two countries began in 2004, when Brazil’s then Minister of Foreign Affairs, Celso Amorim, visited Ankara

As for the notion that some emerging powers might be heading towards a strategy of “soft-balancing,” Hurrell argues that although not every decision that looks like balancing is in fact driven by balance-of-power motivations, one must bear in mind that the utility of balance-of-power theory is not limited to the cases in which a direct security challenge is detected. Strategic options that raise the cost of unilateral action by the hegemon or render it less legitimate are important, since symbolic action is essential to this concept. In this sense, Brazil´s proposal at the UN of the development of a Responsibility While Protecting, as a revision of the R2P principle, is an example of how emerging powers are slowly becoming more confident in taking part in world policy shaping, and attempting to create control mechanisms on the behavior of traditional powers. At the same time, it also points to the necessity for them to assume responsibility, as they engage in a redefinition of their roles in global and regional politics in the post-Cold War setting.25

Brazil and Turkey: Emerging Partners in a Multipolar World

The two countries share similar values, principles, aspirations and expectations for a better future in their respective regions and in a world which is undergoing a rapid transformation.26

The aforementioned shifts affect Brazil and Turkey, as they are two of the so-called emerging powers, but also as states that have demonstrated significant regional and potentially global influence on the governance of international affairs through regional and international institutions. Serfaty refers to the two as the “new influentials.”27

Brazil and Turkey offer interesting case studies of political and economic development in the decade between 2002 and 2012; together they also offer an original case study in terms of the construction of their bilateral partnership, made official in 2010 – at the height of their economic growth – through the signature of a Strategic Partnership Agreement.

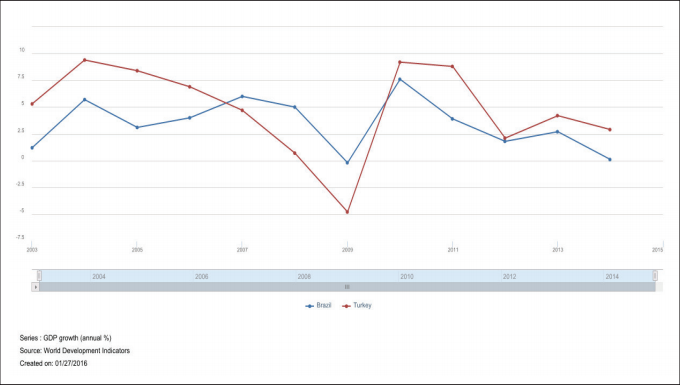

Without doubt the partnership between Turkey and Brazil should be attributed to the fortunate coexistence of a number of decisive variables: while substantially differing in territory, both are big states in their regions, rich in natural resources, with evolving industrial sectors, and with growing economies which fared reasonably well during the economic crisis. The charts below demonstrate the magnitude of the latter factors in the late 2000s, at the peak of their bilateral engagement.

Both Turkey and Brazil represent potentially huge markets, with populations of 75 million and 200 million respectively. The decade between 2002 and 2012 was marked by economic and social progress for both countries: in Brazil over 26 million people were lifted out of poverty during this time and inequality was reduced significantly; in Turkey extreme poverty fell from 13 to 4.5 percent and moderate poverty fell from 44 to 21 percent, while access to health, education, and municipal services substantially improved for the less well-off.28 The decade also offered the two countries multiple opportunities to cooperate on a multilateral level, including their mutual participation in the G20 –the group of leading economies which gained particular prominence in global financial governance as a result of the 2008 economic crisis– and their coincidence as non-permanent members of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) in 2010. Consequently, Turkey and Brazil found complements in each other that led to the strengthening of ties.

A number of concrete initiatives between the two countries began in 2004, when Brazil’s then Minister of Foreign Affairs, Celso Amorim, visited Ankara. Two years later the visit was reciprocated by Abdullah Gül, who at the time was serving as Minister of Foreign Affairs, before assuming the Presidency of Turkey the following year. As a result of these visits and the subsequent intensification of cooperation between the two ministries of foreign affairs, relations between the two countries were advanced through documents such as the bilateral visa waiver agreement (2001), the Agreement on Cooperation in Defense Related Matters (2003), and a series of Memoranda of Understanding in various areas.

In January 2006, Minister Gül’s visit to Brazil spurred the creation of the Turkish-Brazilian Business Council. This regulatory body has members from the Turkish Board of Foreign Economic Relations (DEIK), and members of the São Paulo Federation of Industries (FIESP), from Brazil. The occasion also marked the signing of an agreement providing for the creation of a “High Level Cooperation Committee,” which entered into force on October 8, 2008, after ratification by the Brazilian authorities, and marks the deepening of cultural, political and economic ties between the countries. According to the Briefing Note of the Turkish Embassy in Brazil on August 5, 2011:

The Commission was designed as a mechanism responsible for developing policies and strategies of bilateral common interests of the two countries and cooperation in the fields of economy, trade, science and technology, the arms industry, finance, investment, tourism, culture and political dialogue.29

The exchange of diplomatic visits rose to the highest level with the visit of President Luiz Inacio “Lula” da Silva to Turkey in 2009 and, in the following year, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s visit to Brazil. During PM Erdoğan’s visit, the two states formally proceeded to the signing of the “Action Plan for a Strategic Partnership” (APSP), consolidating the results of their cooperation so far and solidifying their commitment to strengthening bilateral ties.

If personal, high-level friendships among the countries’ leadership were to be identified as the key factor in building the Turkey-Brazil relationship, then the arrival of the Dilma Rousseff administration in Brazil in 2011 would disprove the argument

In 2010, Turkey and Brazil coincided as non-permanent members of the Security Council of the UN and embarked upon an ambitious project to mediate the developing conflict over Iran’s nuclear program. In order to avoid the application of a fourth round of sanctions from the UN, Lula and Erdoğan attempted to reach an agreement with Iran, which denied western accusations regarding its aspiration to develop a nuclear bomb. According to the Teheran agreement, which was signed on the May 17, 2010, Iran would transfer 1200 kilos of enriched uranium (LEU), to neighboring Turkey, where the material would be deposited and continue to be Iranian property. In exchange, the Vienna Group, made up of the U.S., Russia, France and the International Atomic Energy Association (IAEA), would release 120 kilos of combustion necessary for the functioning of Tehran’s research reactor.

It has been argued that the initiative can be explained on the basis of the interests of both countries to contest the global American hegemony and their desire to act as a bridge between the West and East, on one side, and north and south, on the other.30 The action was also interpreted as a sign that the two countries were aspiring to establish their roles as global players. Nevertheless, this coordinated action became the target of both domestic and international criticism. Turkey, a traditional ally of the West and a NATO member, was accused of shifting loyalties, while Brazil was accused of failing to respect international norms.

In the U.S. as well as in Europe, critics of PM Erdoğan and President Lula argued that short-term cooperation with Iran only furthered the objective of gaining more time before a new threat emerged. The Tehran Declaration was rejected by the P5+1. Shortly after, in June 2010, Turkey and Brazil, as non-permanent members of the UN Security Council, voted “no” to UNSC Resolution 1929 imposing sanctions on Iran for failing to comply with previous resolutions concerning its nuclear program, arguing that sanctions undermined the diplomatic approach.

Regardless of its failure to gain approval by the P5+1, the Turkish-Brazilian initiative was interpreted as a profound paradigm shift in international relations: Once common themes in the agendas’ of the two countries were identified and lent themselves to dissatisfaction with the current global governance regime, these emerging countries engaged in cooperation aiming to increase their own participation in regions and issues that have historically been reserved for “Western” decision and policy-making.31

Soon after the Declaration of Teheran, the Turkish Prime Minister visited Brazil. During his visit, the two leaders signed the APSP, on May 27, 2010, consolidating the existing cooperation and reinforcing the commitment to deepening bilateral relations. The document, which has no binding effect, indicated the intention of the signatories to pursue joint projects, and served as a roadmap and basic orientation to the emerging alliance. Moreover, it institutionalized a channel for dialogue at a critical moment for the promotion of joint interests. Thus, the plan promoted cooperation in new areas, from the energy sector, cultural exchanges and education, to energy exploration and R&D. It also provided for annual political consultations at the ministerial level in order to monitor the progress and implementation of its proposals.32

Given the centrality exercised by the Turkish Minister of Foreign Affairs, Ahmet Davutoğlu, in the formulation of contemporary Turkish foreign policy, it is worth mentioning his visit to Brazil in April 2010. Despite past attempts to broaden and deepen relations with non-Western regions, the ascension of the Justice and Development Party (AK Party) and, principally, of Davutoğlu as Minister of Foreign Affairs, gave a new impetus to the shift in Turkish Foreign Policy. Author of the now famous Strategic Depth, Davutoğlu attributes great importance to the geo-strategic location of Turkey and to the status that this location provides Turkey both regionally and globally.33 The AK Party’s foreign policy under Davutoğlu has been conscientious of the structural shifts in the international system triggered by the end of the Cold War and of the subsequent power shift from Europe to Asia and from North to South, referred to in the literature summarized in the introduction of this paper.34Davutoğlu perceives Turkey to be part of a global transformation marked by the ascension of countries with strong economic growth as well as regional and global aspirations. Having witnessed the Turkish ambition for a more significant role in the new global order, the country has shown an increasing interest in previously neglected regions, such as Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America, which has led to the opening of new embassies and the envoy of trade delegations to diverse destinations.35 Davutoğlu’s belief in the proximity between Turkey and the new emerging economies, including the BRICS, reinforces this idea. It is interesting to note that the frequent presence of business people at meetings between Brazilian and Turkish authorities is indicative of the association between the state’s regional initiatives and the search for expansion of economic interests, and thus points to the existence of a mercantile component in the state’s new foreign policy.36

In trying to diverge from a securitization culture and a cautious approach based on hard power, characteristic of the diplomatic tradition of the Kemalist elite, Davutoğlu and the AK Party attributed a significant emphasis on the increased use of economic, political and cultural elements, or rather, soft power, in Turkey’s foreign relationships.37 Davutoğlu’s view of a new global order in progress, is of a more just, multipolar, and participatory world.

For some analysts, the growing interest of Brazil and Turkey in developing modern military technology indicated their will to become less dependent upon foreign equipment, as both countries had significantly increased their participation in military actions abroad in the past few decades

This perception resonates with the world visions of Brazilian foreign policy-makers, and points to constructivist elements in the emerging partnership between the two. Brazil’s South-South agenda, made central in Brazilian foreign policy under Lula, also departs from the vision of a multipolar world where the key to success is diversification of external relations and strong economic growth in order to achieve autonomy and voice (norm-promoting and agenda-setting power) in the international arena.38 The South-South cooperation agenda of the Lula administration is based not only upon obtaining economic benefits, but also the belief in a common identity and in the search for a more just and egalitarian social and economic order, shared by all of its members.39 With regards to cooperation with other periphery states, this view is best expressed through the words of Brazilian diplomat Samuel Pinheiro Guimarães, who stated that the differences and distances between Brazil and other great periphery states, as well as the shared characteristics and common interests, ensure the avoidance of direct competition of interests, and permit the formation of joint political projects.40

If personal, high-level friendships among the countries’ leadership were to be identified as the key factor in building the Turkey-Brazil relationship, then the arrival of the Dilma Rousseff administration in Brazil in 2011 would disprove the argument. As early as October 2011, President Rousseff travelled to Turkey, giving continuity to the strengthening of Turkish-Brazilian relations. While the issue of Iran remained buried in the past, the Rousseff administration and the appointment of Antonio Patriota as Minister of Foreign Affairs on the eve of the Arab Spring, led Brazil to a closer engagement with the Middle East.41 Meanwhile, Turkey was soon to become an “anchor” state in the region. The Brazilian President’s visit was marked by the signature of a joint declaration entitled “Turkey-Brazil: A Strategic Perspective for a Dynamic Partnership,” and by the signing of further agreements for bilateral cooperation in higher education, transportation and justice. At the time, Dilma Rousseff participated in a forum for Turkish-Brazilian business people and expressed Brazilian support for the Turkish position regarding the Palestinian question.42

In the aftermath of the visit, renewed emphasis was given to bilateral cooperation in the area of defense. Cooperation in this area had been initiated in 2003, with the arrival in Brazil of the Turkish Defense Minister, Vecdi Gönül, at the invitation of then Brazilian Minister of Defense, José Viegas Filho. During this visit, the “Agreement on Cooperation in Subjects related to Defense” was signed (August 14, 2003); this agreement came into force in 2007, following internal Brazilian ratification.

The coincidence of “emergence” –a growing economy, stability, and successful social policies– in Brazil and in Turkey acted as a push factor in the depending of their bilateral relations and the nascence of a strategic partnership that included security and defense issues

Turkish Minister of Defense Ismet Yılmaz visited Brazil in May of 2012. In a meeting with his Brazilian counterpart, Celso Amorim, the two discussed the possibilities of a partnership in the industrial production of military equipment. During the meeting it was decided to place a Brazilian military attaché in Turkey and to provide spaces for Turkish military officials in specialized Brazilian military units, such as the Center for Jungle Warfare, in Amazonia. On May 7, 2012, the two ministers signed a letter of intention that expressed the mutual interest in the exchange of experiences and in the development of partnerships in the industrial development of defense. The Brazilian Minister also stated that despite being situated in different geopolitical scenarios, both states had similar defense needs, leading them to pursue the development of modern military projects with national capacity and autonomous technology.43 For some analysts, the growing interest of Brazil and Turkey in developing modern military technology indicated their will to become less dependent upon foreign equipment, as both countries had significantly increased their participation in military actions abroad in the past few decades.44 In their view, the national availability of military technology guaranteed not only strengthened strategic autonomy, but also transformed the countries into potential exporters of sophisticated military technology.45 This interpretation indicates the presence of both idea- and interest-based motivations for the deepening of defense cooperation between the two emerging allies.

Conclusion: Partnership in the Face of Crises

As derived from the above, the coincidence of “emergence” –a growing economy, stability, and successful social policies– in Brazil and in Turkey acted as a push factor in the depending of their bilateral relations and the nascence of a strategic partnership that included security and defense issues. Following 2012, however, a number of those trends have been reversed. In Turkey, the period between 2013 and 2015 was marked by a slowdown of the economy. Election-related uncertainties, geopolitical developments, and concerns over corruption allegations involving the government dampened confidence and weakened domestic demand. After growing 4.2 percent in 2013, the economy slowed to 2.9 percent in 2014. GDP growth in Brazil similarly slowed from 4.5 percent in 2006-10 to 2.1 percent over 2011-14 and 0.1 percent in 2014. In 2015 the country entered a technical recession. Its implications, including the imposition of austere fiscal measures, the reduction of spending,46 the devaluation of its currency, combined with allegations of government corruption, reduced international investor trust in the country. Disenchanted populations in both countries went to the streets in protest against their governments in 2013, leading the respective leaders to refocus their attention on internal policies. In the domain of foreign policy, the turmoil in the Middle East following the Arab Spring and the Syrian conflict led to constraints and dilemmas in Turkish foreign policy with significant implications for its regional powermanship.47 Brazil, on the other hand, has refocused its foreign policy on maintaining a substantial regional role in the face of crises in neighboring Venezuela and Colombia, and political shifts in a number of Pacific Latin American and South American countries. As a result, “both Brazil and Turkey have, more recently, retreated somewhat from the international scene.” 48

The representatives of Turkey, Brazil and Iran hold hands after Iran agreed to a nuclear fuel swap deal in Tehran on May 17, 2010. | AFP PHOTO / ATTA KENARE

The representatives of Turkey, Brazil and Iran hold hands after Iran agreed to a nuclear fuel swap deal in Tehran on May 17, 2010. | AFP PHOTO / ATTA KENARE

Whether the economic and political hardships facing Turkey and Brazil will signify retrogression in bilateral relations remains to be seen. If one adopts the realist understanding of alliances, and Waltz’s assumption that states need allies primarily in order to project more power globally, then the return to a more domestic and regional focus in both countries will substantially reduce national interest in further cultivating the partnership. If, however, engagement so far has led to the creation of shared understandings of the world, as constructivist would have it, then identity rather than interest will maintain the partnership on the agenda.

With that said, a number of doubts can be cast as to whether the shared “identity” between Turkey and Brazil can go deep enough to form the basis of such a tie. Unlike some of Brazil’s BRICS partners, with a strong post-colonial vision of the world and a strong developing country identity, Turkey has a long-standing connection and position in Western institutions such as NATO, is a candidate for EU membership, and has been an OECD member since 1961. In addition, some deep ideological differences have manifested themselves occasionally, for example when, in 2015, the Brazilian Senate adopted a bill referring to the Armenian genocide, a gaffe which led Turkey to recall its Ambassador to Brasilia for consultations.

While the future of Turkey-Brazil relations remains uncertain, the overview of their engagement during the 2000s, and particularly at the height of their economic growth between 2008 and 2012, can offer interesting insights regarding the emerging powers’ coalition-building. Overview has shown, partners are chosen not only because of their instrumental value or due to a long-standing historic relationship, but also because of the possibility that an alliance might help produce systemic shifts in the global distribution of power, rendering it less unequal.49 At the same time, coalitions tend to be more effective if they take place in the realm of political and economic governance, and not in the realm of peace and security issues. Due to the increasingly interconnected nature of the international system in a multipolar world, states are forced to make non-traditional alliances and partnerships, to go beyond typical regional collaborations, and engage with others who share their strategic, economic or political interests. Whether this will continue to be a trend in the future depends on the recalibration of polarities, and on the reshuffling of economic and political power globally, regionally and domestically.

Endnotes

- Simon Serfaty, “Moving into a Post-Western World,” The Washington Quarterly, Vol. 43, No. 2 (Spring, 2011), p. 8, DOI: 10.1080/0163660X.2011.562080.

- Jean-Pierre Lehmann, “The Seven Global Economic Spheres of 2020. What Will the World’s Economic Landscape Look Like in 2020?” The Globalist, January 28, 2011.

- Giovanni Grevi, “The Interpolar World: A New Scenario,” Occasional Paper, No. 79 (June, 2009); Richard N. Haass, “The Age of Nonpolarity: What Will Follow U.S. Dominance?” Foreign Affairs, Vol. 87, No. 3 (2008), pp. 44-56; Thomas P. M Barnett, “The New Rules: Globalization in a Post-Hegemonic World,” World Politics Review, retrieved April 16, 2012, from http://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/articles/11845/the-new-rules-globalization-in-a-post-hegemonic-world; Charles A Kupchan, No one’s World: The West, the Rising Rest and the Coming Global Turn (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).

- Simon Serfaty, “Moving into a Post-Western World,” p. 8.

- Fareed Zakaria, “The Future of American Power: How America Can Survive the Rise of the Rest,” Foreign Affairs Vol. 87, No. 3 (2008), p.18-43; Fareed Zakaria, The Post-American World, (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2009).

- Charles Krauthammer, “The Unipolar Moment,” Foreign Affairs, Vol. 70, No. 1 (2010), pp. 23-33.

- Giovanni Grevi, “The Interpolar World: A New Scenario,” Occasional Paper, No. 79 (June, 2009).

- Richard N. Haass, “The Age of Nonpolarity: What Will Follow U.S. Dominance?”.

- Ian Bremmer, “Welcome to the New World Disorder,” Foreign Policy, retrieved May 14, 2012, from http://foreignpolicy.com/2012/05/14/welcome-to-the-new-world-disorder/.

- Fareed Zakaria. “The Future of American Power: How America Can Survive the Rise of the Rest,”; Fareed Zakaria, The Post-American World.

- Detlef Nolte, “How to Compare Regional Powers: Analytical Concepts and Research Topics,” Review of International Studies Vol. 36, No. 201, pp. 881-901.

- Stefan A. Schirm, “Leaders in Need of Followers: Emerging Powers in Global Governance,” European Journal of International Relations, Vol. 16, No. 2 (2010), pp. 197-221.

- Brian Lai and Dan Reiter, “Democracy, Political Similarity, and International Alliances, 1816-1992,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 44, No. 2 (April, 2000), p. 203.

- George W. Downs, David M. Rocke and Peter N. Barsoom, “Is the Good News about Compliance Good News about Cooperation?” International Organization, Vol. 50, No. 3 (Summer 1996), pp. 379-406.

- Alexander Wendt, “Collective Identity Formation and the International State,” American Political Science Review, Vol. 88, No. 2 (1994), pp. 384-96. See Wendt´s notion of “identification with the fate of the other.”

- Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye, Power and Interdependence, (New York: Longman, 2001).

- Simon Serfaty, “Moving into a Post-Western World,” pp. 7-23.

- Volker Krause and J. David Singer, “Minor Powers, Alliance, and Armed Conflict: Some Preliminary Patterns,” in E. Reiter and H. Gärtner (eds), Small States and Alliances, (Vienna: Physica-Verlag, 2001).

- Kenneth N. Waltz, Theory of International Politics (New York: McGraw Hill, 1979).

- John H Herz, “Idealist Internationalism and the Security Dilemma,” World Politics, Vol. 2, No.2 (January 1950), pp. 157-180.

- Anne-Marie Slaughter, “International Relations, Principal Theories,” in Ruediger Wolfrum (ed.) Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 2.

- Ted Hopf, “The Promise of Constructivism in International Relations Theory,” International Security, Vol. 23, No. 1 (Summer 1998), pp. 171-200.

- Ibid.

- Andrew Hurrel, “Hegemony, Liberalism and Global Order: What Space for Would-be Great Powers?,” International Affairs, Vol. 82, No. 1 (January 2006), pp. 1-19.

- Mehmet Özkan, “Significance of Turkey-Brazil Nuclear Deal with Iran,” Institute of Foreign Policy Studies, University of Calcutta, India (2010).

- Joint Declaration “Turkey-Brazil: A Strategic Perspective for Dynamic Partnership,” Ministério das Relações Exteriores, Assessoria de Imprensa do Gabinete, Nota à Imprensa nº 375, (7 October 2011).

- Simon Serfaty, A World Recast: An American Moment in a Post-Western Order (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2012).

- World Bank Data.

- Embaixada da República da Turquia em Brasília, “Notas Informativas: Relações Bilaterais Entre a República da Turquia e a República Federal do Brasil,” retrieved August 5, 2011 from http://brasilia.emb.mfa.gov.tr/ShowInfoNotes.aspx?ID=128762.

- Özgür Özdamar, “Brazil and Turkey: Transition from Middle to Great Power?” International Studies Association Annual Meeting, Montreal, 2011.

- Oliver Stuenkel, “Have Lula and Erdoğan tamed Ahmadinejad?” Post-Western World (May 17,

2010), retrieved May 17, 2010 from http://www.postwesternworld.com/2010/05/17/did-lula-and-

Erdoğan-tame-ahmadinejad/. - Elena Lazarou, “Regional Powers in Growing Dialogue: The Brazil-Turkey Strategic Partnership and its Implementation,” Global Political Trend Center Brief, No. 2 (May 2011), retrieved from http://www.gpotcenter.org/dosyalar/GPoTBrief_2_MAY2011_ElenaLazarou_EN.pdf.

- Bill Park, Modern Turkey: People, State and Foreign Policy in a Globalized World (New York: Routledge, 2012), p. 107.

- Cengiz Çandar, “Turkey’s ‘Soft Power’s Strategy: A New Vision for a Multipolar World,” SETA Policy Brief 38, December, 2009. In Bill Park, Modern Turkey: People, State and Foreign Policy in a Globalized World (New York: Routledge, 2012), p. 109.

- Ioannis Grigoriadis, “The Davutoğlu Doctrine and Turkish Foreign Policy,” Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP), Working Paper No. 8 (April, 2010). In Park, Modern Turkey: People, State and Foreign Policy in a Globalized World, p. 110.

- Park, op. cit.

- Philip Robin, “The 2005 BRISMES Lecture: A Double Gravity State: Turkish Foreign Policy Reconsidered,” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 32, No. 2 (2006), pp. 207-209 in William Hale, Islamism, Democracy and Liberalism in Turkey: The case of the AKP (New York: Routledge, 2010) pp. 120-121.

- Tullo Vigevani and Gabriel Cepaluni, “A Política Externa de Lula Da Silva: A Estratégia da Autonomia pela Diversificação,” Contexto Internacional, Vol. 29, No. 2 (2007), pp. 273-335.

- Ibid 298.

- Samuel P. Guimarães, “Quinhentos Anos de Periferia,” Porto Alegre: Editora da UFRGS, 1999; In Tulo Vigevani, Gabriel Cepaluni, “A Política Externa de Lula Da Silva: A Estratégia da Autonomia pela Diversificação,” Contexto Internacional, Vol. 29, No. 2 (July/December, 2007), pp. 298-299.

- Guilherme Stolle Paixão e Casarões notes that Brazil’s ties with the Middle East are also inextricably related to the presence of a large Arab-Brazilian community (over ten million people) present in Brazil, most of them of Syrian-Lebanese origin. He also refers to the potentially profitable commercial relations between Brazil and the region. See “Construindo pontes? O Brasil diante da Primavera Árabe,” Ciencia e Cultura, Vol. 64, No. 4, São Paulo, Oct./Dec. 2012.

- “Brasil e Turquia Fortalecem Relação Estratégica em Visita de Dilma a Ancara,” Folha de São Paulo, retrieved October 7, 2011 from http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/mundo/987511-brasil-e-turquia-fortalecem-relacao-estrategica-em-visita-de-dilma-a-ancara.shtml.

- “Brasil e Turquia Estreitam Cooperação no Setor de Defesa,” Defesanet, retrieved May 7, 2012,

from http://www.defesanet.com.br/defesa/noticia/5947/Brasil-e-Turquia-estreitam-cooperacao-no-setor-de-Defesa. - Brazilian involvement in UN peace operations is a specific case in the emerging countries’ search for greater international projection and the ability of the country to bear the costs linked to peace processes, which becomes evident in the case of Brazilian command of the UN Mission to stabilize Haiti (MINUSTAH), initiated in 2004. Brazilian action is part of its diplomatic tradition of participation in policies that it views as promoting international, or national, peace, but also furthers the tacit objective of obtaining a permanent seat on the UN Security Council, and the search for international recognition which is necessary for the status of an emerging power. For more on this, see Rita Santos and Teresa Cravo de Almeida, “Brazil’s rising profile in United Nations peacekeeping operations since the end of the Cold War,” NOREF Report, March 2014. Turkey, in turn, is part of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), in Afghanistan, initiated by a UN resolution in 2001, and whose leadership was transferred to NATO in 2003; Turkey is also a participant in the UN operation in Lebanon (UNIFIL), which it became a part of in 2006. In regard to the operation in Afghanistan, of which Turkey assumed leadership between June 2002 and February 2003, and again between February and August 2005, the discourse adopted to justify Turkish participation was guided, principally, by the existence of common historical ties and a special relationship between the two states (Park, 2012). In Lebanon, Turkish military involvement became more limited once the European states assumed a greater role. However, Turkish engagement has been more visible in the arena of humanitarian aid given to local populations, through intermediaries such as infrastructural projects and other services (ibid. 141). For more information on both countries’ participation in peacekeeping operations, see their peacekeeping profiles at http://www.providingforpeacekeeping.org/2014/04/03/contributor-profile-turkey/ and http://www.providingforpeacekeeping.org/2014/04/03/contributor-profile-brazil/.

- Oliver Stuenkel, “For Brazil and Turkey, a Natural Defense Partnership Deepens,” Post-Western World. (May 21, 2012), retrieved May 21, 2012 from http://www.postwesternworld.com/2012/05/21/for-brazil-and-turkey-a-natural-defense-partnership-deepens/.

- In 2015 Brazil cut its defense procurement funding by 2 billion U.S. dollars.

- For more on this, see Emirhan Yorulmazlar and Ebru Turhan, “Turkish Foreign Policy towards the Arab Spring: Between Western Orientation and Regional Disorder,” Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 17, No. 3 (2015), pp. 337-352.

- Oliver Stuenkel, “Brazil-Turkey: Can the Love Last?,” retrieved from http://www.postwesternworld.com/2013/04/10/brazil-turkey-relations-can-the-love-last/.

- Alcides C. Vaz, “Coaliciones Internacionales en la Política Exterior Brasileña: Seguridad y Reforma de la Gobernanza,” Revista CIDOB, No. 97-98 (2012).