Introduction

Turkey has vast experience with electoral culture and a rich tradition of party politics. It is possible to trace the country’s familiarity with elections, political parties and the parliamentary system to either 1876 or 1908.1 Although the first and second constitutional periods of the late Ottoman Empire did not continue for a long time, the Republic inherited a notable culture of political parties and elections. It was this legacy that paved the way for the emergence of multiple political circles within the First National Assembly,2which led to the War of Independence, and the Second National Assembly, its immediate successor. While the 1924 Constitution intended to nurture a political system with a multitude of political parties,3 a de facto single-party system was put in place when the Kemalist elites, fearing that political opposition would jeopardize their plans to establish a new state and construct a new national identity, shut down the Progressive Republican Party (Terakkiperver Cumhuriyet Fırkası) in 1925.4 Five years later, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk paved the way for the establishment of the Free Republican Party (Serbest Cumhuriyet Fırka) as a pseudo-opposition party, to make the single-party rule appear more democratic, only to renounce the plan 99 days later in order to prevent the potential political costs of providing an alternative to the ruling party.5

In each election since its establishment, the AK Party has defeated its competitors and has recorded a success that has given rise to an academic debate that claims that the AK Party has gained the status of a dominant party

Although a de facto single-party system was in place between 1923 and 1946, Turkey held regular parliamentary and local elections in accordance with the terms, limits and requirements stipulated by the 1924 Constitution. The country, however, did not transition into a multi-party system until 1946. Meanwhile, it is important to note that the lack of judicial oversight, coupled with open ballots and secret counts in the 1946 elections, postponed the introduction of free and fair elections until 1950 –when the authorities allowed multiple political parties to participate in the race and fostered a competitive electoral environment. With the exception of brief transition periods after military coups, therefore, Turkey has been governed by a parliamentary system since the Republic’s foundation in 1923.

From 1946 onwards, the total of 21 parliamentary elections that took place under the multi-party system allowed only two political parties to win three or more consecutive elections: The Democratic Party (DP, 1946-1960) and the Justice and Development Party (AK Party, 2001-present). The AK Party is the only party in the republic’s history to win five consecutive parlimantery elections, hence forming single party governments, with the exception of a brief period between the June 7, 2015 general elections and the November 1, 2015 repeat election, during which period an AK Party-led caretaker government was in place. In addition, although the DP defeated the Republican People’s Party (CHP) in 1950, 1954 and 1957, the party’s popular support dropped from 58 to 48 percent in 1957 while the main opposition CHP enjoyed an increase from 35 to 41 percent and reduced the margin to roughly 7 percent.6 After the first three elections, held under judicial supervision and according to the principles of secret ballot and open count in the multi-party system’s early years, no political party succeeded in recording three consecutive election victories until the 2000s, and no party in Turkey, except the AK Party, has registered four electoral victories in a row since the advent of the multi-party system, nominally in 1946 and genuinely in 1950.

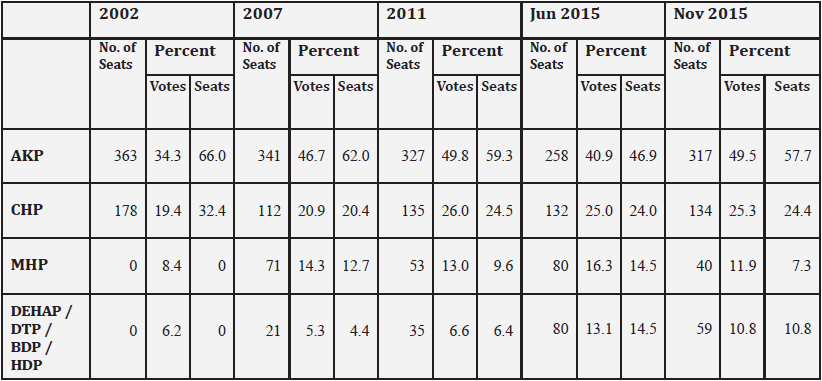

Established in 2001, the AK Party won five consecutive elections in 2002, 2007, 2011, and twice in 2015, and outperformed the DP both by winning more consecutive elections and by steadily increasing its popular support in each election cycle.7 Having won with 34.4 percent in the 2002 parliamentary elections, the party increased its votes to 46.6 percent in 2007, 49.8 in 2011, and 49.5 in the November 1, 2015 parliamentary elections. In contrast with the DP, whose popularity dipped in the 1957 elections, the AK Party, despite a setback in the June 7, 2015 election, today enjoys a steady increase in its popularity while the opposition parties seem unable to improve their records in any significant way, with the exception of the pro-Kurdish People’s Democratic Party (HDP)’s major electoral victory on June 7, 2015, in which it received over 13 percent of the national votes –a figure that was almost twice as much as the pro-Kurdish parties’ traditional electoral performance.8 The main opposition CHP received respectively 19.4, 20.9, 25.9, 25.0 and 25.3 percent of the vote in the five parliamentary elections that resulted in AK Party victories. Putting aside the 2002 election, while the AK Party controls approximately 50 percent of the electorate, the opposition parties compete among themselves for the remaining half.

Three local elections in 2004, 2009 and 2014, two constitutional referendums in 2007 and 2010, as well as the presidential election in 2014 that evolved into an electoral contest between the AK Party and the opposition, would attest to the above analysis, meaning that the AK Party (or the political platform defended by the AK Party) has had a wide lead over its contenders in each of these elections or referandums. In each election since its establishment, the AK Party has defeated its competitors and has recorded a success that has given rise to an academic debate that claims that the AK Party has gained the status of a dominant party, and that the Turkish party system has become a dominant-party system.9 To be sure, the terms dominant party and dominant-party system represent relatively novel concepts for the general public in Turkey. As such, the debate has been largely confined to a small audience that consists of a handful of academics and journalists with an interest in the AK Party’s current and future positions. Despite receiving limited attention from within Turkey, however, these concepts have a vast literature at the international level. The AK Party’s experience in Turkey is a recent addition to this body of the literature.

The existing body of literature about dominant parties largely addresses the following political parties: the Liberal Democratic Party (Japan), the Indian National Congress (India), the Mapai/Labor Party (Israel), the Kuomintang/Chinese Nationalist Party (Taiwan), the Social Democratic Party (Sweden), the Institutional Revolutionary Party (Mexico), the Christian Democratic Party (Italy), the African National Congress (South Africa) and the United Malays National Organisation (Malaysia). The aforementioned political parties have been recognized as dominant parties by virtue of their ability to remain in power for extended periods of time. Only two of them, the African National Congress and the United Malays National Organisation, maintain their position as dominant parties today. The others have been deprived of this status after bowing to their opponents. In other words, the cycle of dominant parties has ended in all countries with the exception of South Africa and Malaysia.10

It is possible to identify certain common themes in the ways in which the large body of literature has analyzed dominant parties, and dominant-party systems in various countries. The emergence of dominant parties, the ways in which they cling to political power as well as the reasons behind their eventual demise are among the common themes. In this sense, it is also possible to identify the factors that facilitate dominant parties’ power as a common theme.11

For the purpose of this article, we will discuss whether or not the AK Party and Turkey have, respectively, evolved into a dominant party and a dominant-party system in light of the AK party’s election victories since 2002.

Conceptual Framework: Dominant Parties and

Dominant-Party Systems

The concepts dominant party and dominant-party system are difficult to separate since they simultaneously come into play during attempts to categorize party systems. In other words, the academic literature on the categorization of party systems often utilizes the two terms together and, not infrequently, almost interchangeably. Both Maurice Duverger’s political science classic, Les Partis Politiques (1993)12 and more recent studies in the same discipline analyze the concepts during their discussions of party systems.

The dominant-party system is a type of party system, which refers a form of classification relevant to the relations between different political parties and the circumstances wherein this relation occurs. Party system can be classified with reference to the number of political parties, openness to competition, the relative power and geographical distribution of electoral support, among others. The most common criterion among these, however, is the number of political parties in a given system. This gauge, which we largely owe to Duverger himself, is still widely utilized to categorize party systems. Duverger’s now-classic assessment, based on the numerical criterion, identified distinct types of party systems such as single-party, Anglo-Saxon two-party, and multi-party.13 It is also important to note that Duverger engaged in discussions about different party systems (i.e. independent parties, alliances, balanced parties, dominant-party systems) that complemented with the above-mentioned categorization.

According to Duverger’s classification, a dominant-party system is based on the “power” criterion. Here, it is noteworthy that the dominant-party system, which emerged in relation to the “power” criterion, tends to complement and unite with party systems with numerical references such as single-party, two-party and multi-party systems. In other words, Duverger emphasized that a given political party could assume the role of a dominant party in both two-party and multi-party systems.14

The assumption of a given political party in either two-party or multi-party systems is associated with power, influence and faith. Here, power refers to the given party being stronger than others, leading its competitors and defeating rivals for an extended period of time. Influence represents a given party’s association with a given time period (being in accordance with zeitgeist of a given period), as well as correspondences between its doctrine, ideas, methods and attitude, and those of the time period.15 Faith, in contrast, refers to the acknowledgement of the party’s superiority and influence over citizens that not only support the party in question but also those who openly express hostility toward it –albeit with some disappointment.16 As such, a given party’s role as a dominant party is closely associated with the popular belief that it is indeed a dominant party. Briefly put, Duverger tends to take into consideration both material and sociological elements in his definition of the dominant party.

The definition of ‘dominant party’ which Duverger presents as part of his classification of party systems, however, has significant gaps and uncertainties. These are not only associated with the sociological element but also extend into his analysis of material factors. Associating power with a given party being stronger than others, assuming a leadership position and remaining superior for an extended amount of time, for example, represents quite an abstract and unclear assessment. What, for instance, is the measure of power in this case? Furthermore, is it enough for a political party to receive more votes than others in order to “lead” its competitors? Finally, what exactly does “an extended period of time” refer to?

The uncertainty which results from the aforementioned questions yields some answers with reference to Duverger. After all, the author did introduce standards for size and leadership. In this sense, he notes that the number of a political party’s parliamentary seats, not the number of its card-carrying members or total votes, must be taken into consideration.17 Moreover, he claims that it might be possible to identify a given political party as a dominant party if and when the party in question succeeds in maintaining an absolute majority over an extended period of time. In other words, Duverger overcomes the unclarity of size and leadership with help from the precondition of controlling an absolute majority of all seats in the legislative chamber. With that said, it is difficult to make the argument that Duverger successfully tackles the uncertainty surrounding the temporal factor. He merely states that a dominant party in a two-party system would not necessarily lose its title if it falls from power as an exception. In other words, he emphasizes the fact that, even if a given party were to lose its absolute majority in the Parliament, it would still be possible to identify a political party that maintains its numerical power for an extended period of time in a two-party system as a dominant party.18 It is nonetheless important, however, to keep in mind that this explanation fails to eliminate the uncertainty hovering over the phrase extended period of time.

A given political party earning the title dominant party in a popular election does not mean that the country has a dominant-party system

Duverger’s definition of the dominant-party system represents a critical point in the field. Even though his work fails to alleviate some of the uncertainties discussed above, it is safe to argue that Duverger’s criteria have created a strong conceptual framework within which future contributors to the dominant party debate have largely operated. Giovanni Sartori, for example, developed a more detailed and deeper analysis of dominant-party systems based on Duverger’s groundwork.19

Sartori’s most general criterion regarding the definition of dominant parties refers to “the party that leads all others in a given polity.” Since “lead” alone would be unclear, however, he introduced a numerical criterion to overcome this problem. Sartori arbitrarily identified the numerical data as 10 percent. In other words, the political party in question becomes a dominant party if and when it leads its closest competitor in any given election by a 10-point margin.20

Studies of party systems tend to utilize the terms dominant party and dominant-party system as largely indistinguishable concepts.21 For a great many authors, the difference between the two terms is merely semantic. These authors tend to concentrate on the majority party to reach untrustworthy conclusions about the nature of the political system. This tendency leads to the assumption that the political system, wherein the dominant party operates, immediately becomes a dominant-party system. In truth, however, there is a need to distinguish the two concepts: Dominant party refers to a type or category of political party. Dominant-party system, however, is a form of party system. A given political party earning the title dominant party in a popular election does not mean that the country has a dominant-party system. For instance, the Democrazia Cristiana in Italy, the Mapai in Israel and the Social Democratic Party of Denmark are all dominant parties. Yet all the aforementioned countries do not necessarily have dominant-party systems.22

Sartori adopts the following distinction to divorce dominant parties from dominant-party systems.23 According to the author, it is possible to identify any party which wins more parliamentary seats than others by a relatively small (i.e. 10 percent) margin as a dominant party. It does not, however, mean that the dominant party’s existence inherently entails the existence of a dominant-party system. To speak of a dominant-party system, many other criteria must be met.

Sartori, much like Duverger, identified seven distinct party systems based on the numerical criterion: single-party, hegemonic party, dominant party, two-party, limited pluralism, extreme pluralism and atomized multipartism.24 Within this categorization, the first three party systems (i.e. single party, hegemonic party and dominant party) resemble Duverger’s single-party system. Similarly, limited pluralism, extreme pluralism and atomized multipartism roughly match Duverger’s multi-party system. Here, the following is rather crucial to note: Sartori includes the dominant-party system within the category of single-party systems with reference to the numerical criterion. When the categorization occurs on the basis of competition, however, the single-party system and the dominant-party system will be categorized separately. After all, one political party accumulates all political power in a single-party system. The existence of another party is absolutely impermissible. In this regard, the single-party system is devoid of competition. In dominant-party systems, in contrast, political parties competing against the majority party are not only allowed to participate in elections but are also legal and legitimate contenders.25 This would mean that the dominant party system, by virtue of openness to competition, clearly distinguishes itself from the single-party system.

Building on Sartori’s theory, we identify just one quality of dominant-party systems: competitiveness, or the de facto and de jure existence of other political parties within the political system. Of course, this criterion alone would be insufficient to identify a given party-system as a dominant-party system. After all, all party systems in Sartori’s categorization, with the exception of single party systems and hegemonic party systems, are open to competition. In this sense, there is need to identify additional criteria in order to distinguish dominant-party systems from the remainder of party systems. One such criterion is the authenticity of victories in competitive elections.26 In other words, the political party in question must hold onto an absolute majority of legislative seats without resorting to election fraud or jeopardizing the fairness of elections.

President of Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, is about to make the opening speech in the first meeting of the 25th term of the Turkish parliament. | AA PHOTO / KAYHAN ÖZER

President of Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, is about to make the opening speech in the first meeting of the 25th term of the Turkish parliament. | AA PHOTO / KAYHAN ÖZER

In determining the necessary conditions for dominant-party systems, Sartori also proposes that the number of legislative seats, in addition to competitiveness and authenticity, be utilized. The political party must not only win elections but also enjoy an absolute majority in the legislative assembly. If a given political party maintains an absolute majority, i.e. one more seat than half of all seats in the legislative branch, for just one term, this would clearly be insufficient to describe the political system as a dominant-party system. The same party must accomplish the same level of support for at least three consecutive terms.27 Only if the political party records such a success can we rightfully refer to a dominant-party system.

Briefly put, Sartori maintains that it would be possible to identify a given country as having a dominant-party system if a given political party manages to control the absolute majority of the legislative branch for at least three consecutive terms as a result of fair and competitive elections. Moreover, Sartori regards domination through coalitions as an impediment to the dominant-party system. The given political party, therefore must, in addition to the above mentioned requirements, also have enough power within the legislative branch to form a single-party government.

Speaking of a dominant-party system first and foremost requires a political party to maintain a notable majority in the Parliament for an extended period of time as a result of victories in elections which meet democratic standards

The above discussion clearly establishes that Duverger and Sartori identified different criteria to identify dominant-party systems. The two accounts, however, have certain points in common: Duverger posits that a sufficient condition of dominant-party systems is for a given political party to control the absolute majority of legislative seats over a long period of time. It is important to note, however, that he added a sociological criterion to his description. Sartori, meanwhile, maintains that the fundamental condition is for a political party to cling to an absolute majority of legislative seats for at least three consecutive terms. It is possible to claim that Sartori developed a clearer theory than Duverger by virtue of making the temporal condition more specific and introducing additional conditions. However, his account does not take the sociological criteria into consideration.

The dominant-party system debate, which has capitalized on the theories of Duverger and Sartori, has been reproduced in a number of more recent studies. For instance, Pempel (1990)28 set forth the following four conditions for the identification of dominant parties: (i) Numerical dominance to control more seats than its competitors. This prevents the identification of second and third parties as dominant parties since the pre-condition of dominant party status involves a majority. (ii) The party must enjoy the advantage of bargaining power. In other words, under normal circumstances, it should assume a position either within a government or during the formation of a government that allows it to effectively negotiate with smaller parties. Furthermore, a given party must assume a position to prevent a government from being formed in its absence even if it does not have a majority in the legislative assembly. (iii) The party must be chronologically dominant in the sense that it should be at the center of political power for not just a few years but throughout a significant time period. (iv) The party must be governmentally dominant. Due to its prolonged presence in central power, the dominant party serves as the implementor of public policies that shape the national political agenda that many would identify as a historic project.29

The leading reason for the overall lack of institutionalization was the closure of parties through the tutelary regime’s direct and indirect interventions

Based on the four elements mentioned above, it is possible to argue that Pempel, like Duverger, views a given party’s control of more seats than others as a necessary condition. In other words, Pempel speaks of majority as opposed to an absolute majority. Moreover, he differs significantly from Sartori in arguing that participation in a coalition government does not jeopardize the party’s position as a dominant party. Thirdly, he adopts a principle similar to Duverger in claiming that dominance ought to remain intact over an extended period of time as opposed to just a few years. In contrast, recalling Sartori’s criterion of three consecutive election victories, Pempel, like Duverger, sets forth an unspecific temporal condition. Finally, he introduces a novel criterion by discussing “governmentally dominant” parties.

It is possible to provide additional examples of attempts to develop criteria to identify dominant parties and dominant-party systems. For example, K. F. Greene (2010)30 sets forth three criteria for dominant parties. (i) Single-party rule represents a threshold of power which would be inaccurately associated with a specific percentage of the vote or parliamentary seats. In contrast, dominance is related to the power of determining public preferences through policies and laws. Absolute dominance over the executive and legislative branches, as well as the impossibility to form a government without the dominant party, form the basis of such power. (ii) Single-party domination implies a temporal threshold which differs according to the observer. This ranges from two elections to 30 or even 50 years, as well as between permanent governments and semi-permanent governments. The most reasonable condition, however, is either four consecutive elections or twenty years.31 (iii) A meaningful election requires competition. It is necessary for opposition powers to form independent political parties and participate in elections. Finally, a meaningful election involves the absence of election fraud that could manipulate election results.32 Two of Greene’s three criteria were also adopted by Duverger and Sartori. In discussing the temporal threshold, Greene, like Sartori, introduces a specific time frame. Meanwhile, his engagement with competitive elections overlaps with Sartori as well. In contrast, Greene’s assessment of the power threshold differs from both Duverger and Sartori. However, Greene has a similar perspective to Pempel in this regard.

Up until this point, we have attempted to draw attention to the criteria that four authors have set forth about dominant party systems. Introducing additional thinkers would not necessarily render the task of identifying common criteria easier.33 In this regard, it would seem that there is no agreed-upon list of criteria that makes it possible for us to speak of dominant party systems. Nonetheless, it is possible to develop certain criteria based on the four approaches we have discussed above. The commonly-featured definition in academic literature is as follows: Speaking of a dominant-party system first and foremost requires a political party to maintain a notable majority in the Parliament for an extended period of time as a result of victories in elections which meet democratic standards.

It is also possible to present the above definition in greater detail: In order to speak of the presence of a dominant party system, i) multiple parties must be allowed to exist in practice and legally, ii) in a competitive election atmosphere, iii) where fair and transparent elections are held, iv) to allow a party to control the majority of parliamentary seats, v) not only for one election cycle but for at least three or four elections or twenty years, vi) rely on not only numerical but also sociological power, vii) control not only numerical but also administrative power, viii) maintain not only numerical power but also the ability to determine societal preferences, ix) make it impossible for other parties to form a government in its absence, x) and finally, maintain its dominance either by forming single-party governments or by positioning itself as an indispensible coalition partner.

Political Parties and Party Systems in Turkey

Turkey has a long history with political parties, which began with the establishment of the Committee of Union and Progress (İttihat ve Terakki Cemiyeti) in 1889. Short of an exact figure, it is possible to estimate that over 300 political parties have been active in the country ever since.34 The military that perpetrated a coup in 1980 outlawed all active political parties at the time, only to allow citizens to form parties three years later. While 79 of the parties that were established between 1983 and 2014 remain active, 11 new parties were founded in 2012 with 10 more becoming the latest to join a long list of parties the following year.35

Although the above figures are indicative of an intense desire for political participation in Turkey, they do not necessarily entail positive implications on the level of institutionalization among political parties. Turkey’s political system, despite 125 years of experience with party politics, has failed to facilitate institutionalization due to a number of factors. The leading reason for the overall lack of institutionalization, however, was the closure of parties through the tutelary regime’s direct and indirect interventions. The inability of political parties to remain active over long periods of time has created ruptures in their tradition and cadres to effectively limit the possibility of institutionalization. The first such rupture took place during the transition from the Ottoman Empire to the Republic. During the republican period, the Kemalist elites monopolized political power by shutting down all parties with the exception of the Republican People’s Party (CHP), and prevented the establishment of new parties until 1946 so that the CHP would serve as the sole political party in the country. However, in the aftermath of the 1946, when the nominal advent of the multi-party system occurred, citing the security of the regime and the state as pretext, military tribunals and the Constitutional Court have often banned political parties they deemed harmful. Since its establishment in 1961, the Constitutional Court has shut down 27 parties with reference to the principles of “secularism” and the “indivisibility of the state.”36 As such, the regime’s security concerns have regularly trumped democratic politics and the people’s right to political participation from the Republic’s foundation onwards.37

President elect, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, congratulating the new leader of the AK Party, Ahmet Davutoğlu, after the first Extraordinary Congress on August 27, 2015. | AA PHOTO / VOLKAN FURUNCU

In this respect, the bans against political parties to which military tribunals and the Constitutional Court have resorted over the years have had a negative influence on the institutionalization of these organizations. As outside interventions rendered it impossible for political parties to remain active over extended periods of time, political parties have simultaneously been unable to perform well or to remain in power for long. As a matter of fact, the only party to achieve a relatively extended period of time in power –prior to the rise of the AK Party in 2002– was the Democratic Party (DP), which won three consecutive elections between 1950 and 1960, when a military coup ousted the party from power. More recently, the AK Party is the only example of a party that has outperfomed the DP by securing enough legislative seats in the 2002, 2007, 2011, and 2015 parliamentary elections to form single-party governments. The party also outperformed its competitiors in the 2004, 2009 and 2014 local elections. Briefly put, the AK Party remains an organization that has won comfortable victories in each election cycle since its establishment.

The main prerequisites for identifying a given country’s party system as a dominant-party system are the existence of a competitive electoral environment and the organization of elections in a fair and transparent manner

Turkey’s constitutions have consistently advocated a multi-party system. In certain time periods, however, single-party and two-party systems have emerged either de facto or as a result of voter preferences. Between 1923 and 1946, for instance, the ruling CHP implemented a de facto single-party system in the country. Following the introduction of a multi-party democracy in 1946, two parties (the CHP and the DP) gained control of the Parliament and ushered in a two-party system for the next four years. In the 1950 elections, the Nation Party (MP) won a parliamentary seat alongside the DP and the CHP to create a multi-party system, which remained intact through all election cycles between 1950 and 2002. It is possible to argue that Turkey largely had a multi-party system during this long period of time, since more than two parties managed to secure representation in the legislative branch in each election year.

The allocation of parliamentary seats between two parties (the AK Party and the CHP) in the November 2002 parliamentary elections, however, engendered a two-party system for the next four years.38 In 2007, 2011 and 2015, in contrast, four political parties secured representation at the legislature. The four-party structure, featuring the AK Party, the CHP, the MHP and various forms of the pro-Kurdish political parties (independent parliamentarians that formed the Democratic Turkey Party (DTP) and, later, the Peace and Democracy Party (BDP), and the People’s Democratic Party (HDP)), restored the multi-party system in the country. The fact that the AK Party won all four parliamentary elections by a comfortable margin over its competitiors ushered in the debate as to whether Turkey has turned into a dominant party system in earnest.39

Turkey: A Case of a Dominant Party System

The main prerequisites for identifying a given country’s party system as a dominant-party system are the existence of a competitive electoral environment and the organization of elections in a fair and transparent manner. Taking into account the parliamentary elections of 2002, 2007, 2011 and June and November 2015, it is safe to claim that Turkey meets both criteria with relative ease.40 Barring aside the June 7, 2015 election, all the aforementioned elections, furthermore, led to the allocation of the majority of legislative seats to a single party.

At this point, it is important to note the following: There is no consensus over the temporal criterion in the discussion of dominant-party systems. Sartori argued that one of the necessary conditions of a dominant-party system was for a political party to control an absolute majority of parliamentary seats for at least three consecutive elections.41 Greene, in contrast, identified the necessary condition as four consecutive elections or twenty years in power. (In cases where a political party has not yet won four consecutive elections, Greene prefers the term proto-dominant party system.42) Based on both Sartori and Greene’s criteria, Turkey already is a dominant-party system.43

Turkey’s General Election Results

As the above table clearly indicates, the AK Party meets Sartori and Greene’s criterion of winning an absolute majority of parliamentary seats, respectively, in three or four consecutive elections. The party claimed 66 percent of seats in 2002, 62 percent in 2007, 59.3 percent in 2011 and 57.7 percent in the November 201544 elections. Notably, the margin between the AK Party’s seats and the main opposition CHP’s share has remained considerably large throughout these election cycles.

In the aftermath of the 2002 parliamentary elections, it was entirely impossible to form a government without the AK Party. Furthermore, the party won enough seats to have no need for a coalition partner in order to form governments in 2002, 2007, 2011 and (November 1) 2015. Although numerically possible, it soon emerged that it was politically impossible to form a government excluding the AK Party in the aftermath of the June 7, 2015 election, a situation which produced a hung parliemanet and led to an early eletion. Therefore, two necessary conditions of the dominant-party system were fulfilled with relative ease.

The AK Party has been the leading actor when it comes to the country’s political agenda. The fact that almost all elections easily turn into a de facto referandum on the AK Party’s political performance and its future projections confirm this point

In order to identify a given political party as a dominant party or to speak of a dominant-party system based on a given party’s election victories over an extended period of time, it is necessary for the party’s power to rest on not only numbers but also sociology. What this criterion of Duverger indicates is that a given party’s numerical power is not sufficient to call it a dominant party. In addition to this, both the party’s supporters and its opponents must acknowledge its power and influence –a criterion which the AK Party also satisfies. Since 2002, the AK Party has been the leading actor when it comes to the country’s political agenda. The fact that almost all elections easily turn into a de facto referandum on the AK Party’s political performance and its future projections confirm this point. Prior to the parliamentary elections, public discourse doesn’t focus on a comparative analysis of different political parties contending visions. Instead, the departure point of both pro and anti-AK Party camps is an almost exclusive focus on the AK Party’s deeds, discourse, and projection.

Moreover, through administrative, legal and constitutional reforms, the party has eliminated the military establishment’s influence over civilian politics.45 Similarly, until recently, a number of political demands and problems that had been long excluded from politics on the basis of ensuring the regime’s future and security, have been resolved through the AK Party’s agency. For instance, the religious-conservative community’s requests for religious education and freedom of attire were addressed.46 Similarly, despite the recent return of the Kurdish issue in its conflictual form, Turkey has never before approached the Kurdish issue through political and civilian lenses to the extent that as it has under the AK Party governments.47

During this entire period, the AK Party was able to overcome challenges through its sustained popular support. An AK Party-spearheaded constitutional referendum that introduced 24 amendments on 12 September 2010, for instance, was approved with 58 percent of the vote. Similarly, the AK Party’s ability to increase its electoral support in each election that followed the structural reforms would suggest that the party rests on a strong social base. A closer examination of several data sets from the most recent local elections on 30 March 2014 reveals what kind of popular support the AK Party enjoys and how widespread its support is. The local election results established that, while the AK Party has a strong presence across the nation, opposition parties have derived support from a handful of strongholds but have been almost non-existent outside these regions. Out of the total 81 provinces, the AK Party won over 50 percent of the vote in 29 cities and broke the 40-percent mark in another 50 provinces. Only in two provinces, Tunceli and Iğdır, did the party receive less than 20 percent of all votes.48 The aforementioned numbers indicate that the AK Party enjoys strong popular support in all parts of the country and receives votes from a large social group.

The fact that almost 5 million people changed the colors of their votes in favor of the AK Party within such a short span of time to overcome the gathering political and economic instabilities confirms the political dominance of the AK Party

This picture was further confirmed in the aftermath of the November 1, 2015 parliamentary elections. In comparision to the results of the June 7 elections, the AK Party increased its votes by almost 9 percentage point, which numerically meant approximately 5 million extra votes within less than six months. More importantly, “this increase did not occur as a result of a certain segment of society flocking into the AK Party’s ranks and files in droves. Instead, the AK Party increased its votes all across Turkey. It gained back a chunk of pious’ Kurds votes which it had lost to the pro-Kurdish HDP in the June 7 elections. It received a significant number of the votes from the Turkish nationalist Nationalist Action Party (MHP), and other small Islamist and nationalist parties. It benefitted from the high-electoral turn-out. It was the winner in all seven geographic regions of Turkey, including the secularist stronghold of the Aegean, and Kurdish nationalist-dominated Eastern and South-Eastern Anatolia.”49

Furthermore, the inability of the opposition to form a government in the aftermath of the June 7, 2015 general elections, wherein the AK Party lost its parliamentary majority for the first time since 2002, and which produced a hung-parliament, illustrated the centrality of the AK Party in Turkey’s political system. Despite the early euphoria and optimism, the public and political opposition soon found out that there was no possibility of forming a government composed of opposition parties solely. All plausible government scenarios necessitated the inclusion of the AK Party as the senior partner. In addition, during the interval period between the June 7 election and the November 1 repeat election, the Turkish public experienced the prospect of economic uncertainty and political instability, as the business of forming a lasting coalition government proved to be untenable, for the first time since 2002. The fact that almost 5 million people changed the colors of their votes in favor of the AK Party within such a short span of time to overcome the gathering political and economic instabilities confirms the political dominance of the AK Party in Turkey.

As the above indicators would suggest, a sizeable social group closely associates their own socio-economic mobilization with the continuation of AK Party rule.50 Furthermore, a number of academic studies confirm that many social groups, which had been economically and politically victimized by the political system in earlier years, regard AK Party rule as an opportunity to compensate for their victimhood and to benefit from the political system.51 The most obvious indications of this situation are embodied in the socio-economic profile of the party’s voter base. With the notable exception of the Kurdish political movement in Turkey, the AK Party represents more members of victimized social groups than all other political parties at the Parliament in particular and the political system in general.52 Analyses of the party’s supporters also demonstrate that it is more representative of the general population than other political parties with regard to education levels and average age, among other key indicators.53

In this respect, the secret to the AK Party’s consecutive election victories has been its ability to signal to a sizeable chunk of Turkish society that the party serves as the main driver of their social-economic mobilization and continues to serve as the leading advocate for their demands and desires. Winning five parliamentary elections, three municipal contests as well as two referendums and one presidential election, clearly indicate that a significant chunk of Turkish society regards the AK Party as the only capable political agent that can deliver a better future.

The situation at hand in Turkey also confirms that what Nur Vergin described as “the union of sociology and politics” to account for the AK Party’s election victories back in 2004 remains a valid explanation a decade later. Vergin identified the secret to the AK Party’s success as its ability to connect with Turkey’s society.54

Another criterion which we introduced to identify dominant-party systems was that the political party in question would not only enjoy influence in terms of numbers but also with regard to administrative affairs. In this regard, it is difficult to claim that the AK Party adequately fulfilled the aforementioned criterion in the immediate aftermath of the 2002 parliamentary elections. In the early years of the AK Party, the existence of a military-led tutelary rendered it difficult for the AK Party to translate its electoral dominance into administrative dominance. Yet, this picture has changed considerably in recent years. Significant progress has been achieved in regard to the elimination of the the political influence of the bureaucratic establishment, a change which has facilitated the ground for the AK Party to control administrative power as well.55 In other words, as the military retreated from the political scene and the previously meddlesome high bureaucracy’s power was curtailed, the AK Party’s power in terms of administrative capability increased significantly.

Our assessment, which takes into consideration nine criteria that we set forth, clearly reveals the following: Adopting both Greene’s four consecutive elections, and Sartori’s,three consecutive elections, position to address the temporal criterion, the AK Party’s consecutive election victories since 2002, coupled with its administrative power, illustrate that the AK Party is a dominant party and Turkey has evolved into a dominant-party system.

Endnote

- The first general elections in the Western sense of the term took place, in the absence of an electoral law, for the purpose of establishing an Assembly of Representatives (Meclis-i Mebusan) in accordance with the Constitution of 1876. The first parliamentary elections that took place according to an electoral law and with the participation of political parties, however, did not occur until 1908. It is possible, though, to argue that local elections date back to an earlier period. For a comprehensive study of the history of elections in Turkey, see Ahmet Yeşil, “Türkiye’nin Seçim Deneyimleri Işığında Temsilde Adalet mi Yönetimde İstikrar mı?” (In Light of Turkey’s Electoral Experiences: Just representation or stable government?), Türkiye Günlüğü, No. 97 (2009), pp. 122-141; M. Ö. Alkan, “Türkiye’de Seçim Sistemi Tercihinin Misyon Boyutu ve Demokratik Gelişime Etkileri” (Turkey’s Choice of Electoral System: Mission and Influence on the Democratic Progress), Anayasa Yargısı, No. 23 (2006), pp. 133-165.

- For more a detailed account of political pluralism in the first National Assembly, see, Ahmet Demirel, 1. Meclis’te Muhalefet: İkinci Grup (Opposition in the First Assembly: The Second Group), (İstanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 1995); İhsan Güneş, Birinci Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi’nin Düşünsel Yapısı (The Ideological Structure of the First Grand National Assembly of Turkey), (Eskişehir: Anadolu Üniversitesi Yayınları, 1985).

- For a better understanding of 1924 Constitution, see Kemal Gözler, Türk Anayasa Hukuku (Turkish Constitutional Law), (Bursa: Ekin Kitabevi Yayınları, 2000, pp. 57-75).

- There is a growing literature on the activities and legacy of the Progressive Republican Party (Terakkiperver Cumhuriyet Fırkası). See, Ahmet Yeşil, Terakkiperver Cumhuriyet Fırkası, (İstanbul: Cedit Neşriyat, 2002); Erik Jan Zürcher, Political Opposition in the Early Turkish Republic: The Proggressive Republican Party, 1924-1925, Leiden, E. J. Brill, 1991.

- The Free Republican Party’s short-lived opposition sheds light on the nature of the regime that was put in place after the Kemalists prevailed over all other contenders during the early republican period. For a detailed account of the party, see Cem Emrence, 99 Günlük Muhalefet: Serbest Cumhuriyet Fırkası, (İstanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2006).

- For details, see: http://tuikapp.tuik.gov.tr/

secimdagitimapp/secim.zul. - Percentage-wise, the AK Party steadily increased its votes in the 2002, 2007, and 2011 elections, Its votes’ share respectively stood as following: 34.3, 46.7, 49.8 percent. But in the June and November general elections of 2015, it had a different experience, while losing almost 9 percentage points in the June 7 election, as compared to the 2011 results, it swiftly recovered them in November 1 election.

- The pro-Kurdish People’s Democracy Party (HDP) significantly increased its votes in the 2015 elections in comparison to previous elections. While it received over 13 percent of the vote in the June 7 elections, its share of the vote dropped to around 10.7 percent in the November 1 election. But the HDP is unlikely to endanger the AK Party’s electoral dominance and single party rule on its own any time soon.

- See Sabri Sayari, “Towards a New Turkish Party System,” Turkish Studies, Vol. 8, No. 2 (2007), pp. 197-210; Meltem Müftüler-Baç and E. Fuat Keyman, “Turkey Under the AKP: The Era of Dominant–Party Politics,” Journal of Democracy, Vol. 23, No. 1 (January 2012), pp. 85-99; Ali Çarkoğlu, “Turkey’s 2011 General Elections: Towards a Dominant Party System?” Insight Turkey, Vol. 13, No. 3 (2011), pp. 43-62; Sebnem Gümüşçü, “The Emerging Predominant Party System in Turkey,” Government and Opposition, Vol. 48, No. 2 (2013), pp. 223-244; B. Esen and S. Ciddi, “Turkey’s 2011 Elections, An Emerging Dominant Party System?” MERIA Journal, Vol. 15, No. 3 (2011), http://www.gloria-center.org/

2011/10/turkey%e2%80%99s-2011- elections-an-emerging- dominant-party-system./; E. Fuat Keyman, “The AK Party: Dominant Party, New Turkey and Polarization,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 16, No. 2 (2014), pp. 19-31; E. Fuat Keyman, “AK Parti: Egemen Parti ve Yeni Türkiye” (The AK Party: Dominant Party and New Turkey), İletişim ve Diplomasi, Special Issue, (2014), pp. 143-151. - For a discussion on the topic see, Kaßner, Malte, The Influence of the Type of Dominant Party on Democracy: A Comparison Between South Africa and Malaysia, Springer Science & Business Media, 2013.

- For discussions about said themes, see: Uncommon Democracies: The One-Party Dominant Regimes, ed. T. J. Pempel, (London: Cornell University Press, 1990); Comparative Democratization and Peaceful Change in Single-Party-Dominant Countries, ed. Marco Rimanelli, (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999); and The Awkward Embrace: One-Party Domination and Democracy, ed. Hermann Giliomee and Charless Simkins, (Taylor and Francis e-Library, 2005).

- Originally published in 1951.

- Duverger’s classification of party systems based on quantitative data and the number of parties active in a given political system has been strongly criticized by a number of academics due to its failure to account for diversity within each group (i.e. single-party, two-party, multi-party), or to consider various sociological elements not associated with quantitative data. For instance, what Duverger identifies as the “single-party” system refers to at least three distinct types of single-party systems: predominant parties, hegemonic parties, and the single-party par excellence. The predominant party system involves a multitude of political parties which represent genuine and independent rivals of the predominant party and compete under equal terms. As such, the system is inherently pluralistic. Meanwhile, hegemonic party systems, while allowing opposition parties to remain active, do not permit them to compete with the hegemonic party on equal ground. Simply put, there is no inter-party competition for political power to change hands. Finally, the third case is the true single-party system where opposition parties exist neither de jure nor de facto. In this regard, it is clear that Duverger’s classification of party systems does not distinguish these various and different manifestations of single-party rule. For a more detailed discussion, see: Ergun Özbudun, “M. Duverger’in “Siyasal Partiler”i ve Siyasal Partilerin İncelenmesinde Bazı Metodolojik Problemler” (The ‘Political Parties’ of M. Duverger and Some Methodological Problems with the Study of Political Parties), Ankara Üniversitesi Hukuk Fakültesi Dergisi, Vol. 21, No. 1-4 (1964), pp. 23-51.

- Maurice Duverger, Siyasi Partiler (Political Parties), tr. Ergun Özbudun, (Bilgi Yayınevi, 1993), p. 398.

- Ibid. p. 298.

- Ibid. p. 399.

- Ibid. pp. 365-7.

- Ibid. p. 398.

- For the purpose of addressing some uncertainties in Duverger’s theory, Sartori’s Parties and Party Systems: A Framework for Analysis (2005) represents one of the main resources available.

- He does, however, make a note here. According to Sartori, quantitative data is necessary but by itself not sufficient to allow for a political party to be identified as a dominant party, since there were over 20 countries and political parties that met the 10-point-margin criterion between the years 1965 and 1972 –a wide range of cases including Iran, Uruguay, Mexico, the Philippines, France and Turkey. At this point, one of the most significant questions to pose relates to whether or not the leadership position depended on election fraud. After all, this question, among other criteria, is of utmost importance for the concept of dominant party. In places with no free and fair elections, it would be more suitable to speak of hegemonic parties, rather than dominant parties. See Giovanni Sartori, Parties and Party Systems, (UK: ECPR Press), 2005, pp. 171-172.

- For an analysis of different definitions of both terms, see Bogaards, Matthijs, “Counting Parties and Identifying Dominant Party Systems in Africa.” European Journal of Political Research, Vol. 43, No. 2 (2004), pp. 173-197.

- Ibid. p. 173.

- Sartori’s approach, for many scholars, sets him apart from other scholars of the dominant party and dominant part system theory. His distinction between these two terms and quantitative clarification of them earned him many disciples in the field. For instance, Matthijs Bogaards argues that Sartori’s counting rules, party system typology and definition of a dominant party are still the most helpful and analytical tools for classification of party systems and their dynamics in general, and of dominant party systems in particular. He then further expounds the advantages of Sartori’s framework of analysis, which he asserts to be fivefold. “First, Sartori’s counting rules are not strictly based on relative size, but on the number of relevant actors in electoral competition and government formation. Second, Sartori’s analysis employs a conception of dominance absent in continuous measures of party number. Third, the distinction between dominant and dominant authoritarian party systems encourages an identification of the nature of dominance. Fourth, dominant party systems are embedded in a typology of party systems. In fact, there are two typologies: one for structured party and one specially designed for Africa’s fluid polities and unstructured party systems. Finally, and decisively, Sartori’s counting rules, his definition of a dominant (authoritarian) party system, and typology of party systems provide a unified and coherent framework of analysis that is sensitive to context and time.” See, Matthijs Bogaards, “Counting Parties and Identifying Dominant Party Systems in Africa,” pp. 173-174.

- Giovanni Sartori, Parties and Party Systems, pp. 171-178.

- Ibid. p. 172.

- Ibid. p. 173.

- Ibid. pp. 174-175.

- T. J. Pempel, “Introduction: Uncommon Democracies: The One-Party Dominant Regimes, in Uncommon Democracies The One–Party Dominant Regimes, ed. T. J. Pempel, (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1990), pp. 1-32.

- Ibid. p. 4.

- Kenneth F. Greene, “The Political Economy of Authoritarian Single-Party Dominance,” Comparative Political Studies, Vol. 43, No. 7 (2010), p. 809.

- The standard/threshold that Greene identifies has a legitimate basis within the author’s theory. Pushing the threshold further up would leave Taiwan’s KMT, an obvious example of authoritarian dominant parties, outside the category. In contrast, lowering the threshold would lead a number of cases, which would make it difficult for the author to suggest that a stable pattern has emerged in association with inter-party competition, wherein parties could be identified as dominant parties. For instance, while it might be tempting to identify ruling parties in various African nations as dominant parties, not enough time has passed to reach a conclusion after one or two election victories. Greene describes such cases, which have yet to reach the threshold for durability, as proto-dominant party systems. See Greene, “The Political Economy of Authoritarian Single-Party Dominance,” p. 810.

- Ibid. p. 810.

- For a study that summarizes the said situation, see: Nicola Louise de Jager, Voice and Accountability in One Party Dominant Systems: A Comperative Case Study of Mexico and South Africa, PhD. Theses, University of Pretoria, (2009).

- To see the whole list of these parties: http://www.tbmm.gov.tr/

kutuphane/siyasi_partiler.html ; http://www.yargitaycb.gov.tr/ belgeler/site/documents/ SPartiler04062014.pdf. - To see the list of parties that were established since 1983: http://www.yargitaycb.gov.tr/

belgeler/site/documents/ SPartiler04062014.pdf. - For a comparative assesment of Turkey’s Constitutional Court and the European Court of Human Right’s approaches to the political parties, see: Sevtap Yokuş, Türk Anayasa Mahkemesi’nin ve Avrupa İnsan Hakları Mahkemesi’nin Siyasi Partilere Yaklaşımı (Turkish Constitutional Court’s and European Court of Human Rights’s Approach towards Political Parties), Yokuş, http://dergiler.ankara.edu.tr/

dergiler/38/288/2629.pdf. - Together with the constitutional amendments that took place in 2010, the range of acts for political parties to be shut down were restricted to a large extent, which made it more challenging to close them down with reference to secularity and the indivisibility of the state. See Ersin Kalaycıoğlu, “Kulturkampf in Turkey: The Constitutional Referandum of 12 September 2010,” South European Society and Politics, Vol. 17, No. 1 (2012), pp. 1-22; Yusuf Şevki Hakyemez, “2010 Anayasa Değişiklikleri ve Demokratik Hukuk Devleti,” (Constitutional Amendments of 2010 and Democratic Legal State), Gazi Üniversitesi Hukuk Fakültesi Dergisi, Vol. 14, No. 2, 2010, pp. 387-406.

- See Sabri Sayari, “Towards a New Turkish Party System,” p. 206.

- Meltem Müftüler Baç and E. Fuat Keyman give a detailed account of the AK Party’s successive successes at the elections between 2002-2012. They do not focus on the difference between ‘dominant party’ and ‘dominant party system,’ yet they shed light on how the AK Party’s successive victories at three elections amount to its being regarded as a dominant party. For the full discussion, see Meltem Müftüler-Baç and E. Fuat Keyman, “Turkey Under the AKP: The Era of Dominant-Party Politics,” pp. 85-99. In other work, Keyman gives a detailed account of the AK Party’s transition from electoral hegemony to dominant party status, and the challenges ushered in as a result of this transition.

- For instance, the Sustainable Governance Indicators (SGI) report authored by Cemal Karakaş, Omar Genckaya, Subidey Togan, and Roy Karadag clearly denotes the 2011 general elections as being conducted in a free and fair manner. See Cemal Karakaş, Omar Gençkaya et. al., Sustainable Governance Indicators: Turkey Report, Bertelsmann Stiftung, (2014).

- Sartori denotes attainment of three consecutive absolute majorites as the key feature of the predominant party system, provided other conditions are met. In responding to the questions “how long does it take for a predominant party to establish a predominant system?” Sartori argues that “three consecutive absolute majorities can be a sufficient indication, provided that the electorate appears stabilised, that the absolute majority threshold is clearly surpassed, and/or that the interval is wide (between first and second parties). Conversely, to the extent that one or more of these conditions do not obtain, a judgement will have to wait a longer period of time to pass.” See Giovanni Sartori, Parties and Party Systems, pp. 175-177.

- Kenneth F. Greene, The Political Economy of Authoritarian Single-Party Dominance, p. 810.

- Of course, we hereby accept that the distribution of votes between parties, which Sartori touches upon, has become stable and the margin of votes/seats between the first and second party (i.e. the AK Party and the CHP) remains considerably large. As a matter of fact, this statement corresponds with the aforementioned study that KONDA conducted in the aftermath of the local elections on March 30, 2014. See KONDA, 30 Mart: Yerel Seçimler Sonrası Sandık ve Seçmen Analizi, (16 April 2014), İstanbul, pp. 1-78.

- As regards the 2015 elections, this article primarily focuses on the outcome of the November 1, 2015 elections, since the June 7 election failed to produce a functioning government, and hence paved the way for the November 1 repeat election.

- To read more on the transformation in Turkey’s civil-military relations, see, Metin Heper, “Civil-Military Relations in Turkey, Toward a Liberal Model?” Turkish Studies, Vol. 12, No. 2 (2011), pp. 241-252; Müge Aknur, “Civil-Military Relations During the AK Party Era: Major Developments and Challenges,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 15, No. 4 (2013), pp. 131-150.

- For instance, in the democratization package announced on September 30, 2013, the government lifted the headscarf ban for public servants. To see the content of the democratization package, see “Government takes steps on headscarf, Kurds, electoral system,” Hurriyet Daily News, http://www.hurriyetdailynews.

com/government-takes-steps-on- headscarf-kurds-electoral- system.aspx?PageID=238&NID= 55393&NewsCatID=338 (last visited 15 May 2014) . - To gain a deeper understanding of the AK Party’s Kurdish policy, see Mesut Yeğen, “The AK Party and the Kurdish Question: Conflict to Negotiation,” January 2014, Al Jazeera Center for Studies.

- See, KONDA: 30 Mart: Yerel Seçimler Sonrası Sandık ve Seçmen Analizi (An Analysis of Polls and Voters after the March 30 Local Elections), (16 April 2014, İstanbul), p. 72.

- Galip Dalay, “AK Party Is Back on Stage with Force and Responsibility,” Al Jazeera, November 2015.

- Galip Dalay, “AK Parti’de Liderlik ve Kadro,” (Leadership and the cadre in the AK Party), Al Jazeera Turk, 6 May 2014, http://www.aljazeera.com.tr/

gorus/ak-partide-liderlik-ve- kadro. - A recent KONDA report, entitled An Analysis of Polls and Voters after the March 30 Local Elections, features various data pointing to this situation. With the exception of the BDP/HDP, the AK Party was more popular among lowest-income voters, lowest-income communities as well as religious Muslims and the Kurds, who had suffered the most aggravated problems under the Kemalist regime, than other political parties that currently have parliamentary seats. See KONDA, 30 Mart: Yerel Seçimler Sonrası Sandık ve Seçmen Analizi, pp. 15-30.

- Ibid. pp. 18-27.

- Ibid. pp. 16-20.

- Nur Vergin, “Siyaset ile Sosyolojinin Buluştuğu Nokta,” (The Point Where Politics and Sociology Meet), Türkiye Günlüğü, No. 76 (2004), pp. 5-9.

- For a more thorough and focalized analysis of the AK Party being administratively more dominant, see Şebnem Gümüşçü, “The Emerging Predominant Party System in Turkey,” p. 227-229.