Introduction

The recent June 7th and November 1st general elections in Turkey let us witness a great change in the electoral decisions of the Turkish public in a time span as short as five months. The incumbent AK Party received 40.87 percent of the overall valid votes in the June elections –a 9 point fall

compared to its performance in the previous general elections of 2011. With these results, the AK Party lost its privilege to form a single party government for the first time since 2002. The party had come to power with the 3 November 2002 general elections and had increased its votes for the following two general elections in 2007 and 2011. Hence, the June elections of 2015 were extraordinary for the public, who were used to seeing the AK Party’s easy wins in terms of the distribution of parliamentary seats and the consolidation of its dominant party position over time.1Following the June 2015 elections, the incumbent AK Party and the main opposition party CHP could not conclude their coalition negotiations successfully and the Parliament called for a snap election while an interim election government was formed to govern the country. Only five months after the June elections, the AK Party increased its votes to 49.5 percent in the snap elections of November 1st, 2015 by increasing its votes by 9 points with an increase of about five million votes. What caused such a radical shift in the electoral behavior of the voters? What led those five million voters to swing their votes and choose to vote for the AK Party?

The economy was a central issue of the June elections whereas its primacy was shadowed by rising security and identity-related issues preceding the November elections

This article compares the role of the economy in Turkey’s June and November general elections. It argues that the two elections, in terms of the context in which they were carried out in and the determinants of their results, differ to a great extent with regard to the economic factor. This difference played a great role in the results of the June and November elections. In a nutshell, while the Turkish economy was generally on a downward trend in the atmosphere of the June elections, some indicators, such as current account balance, improved slightly, and some other indicators, such as the growth rate, improved beyond expectations before the November elections. Such improvements, together with the inability of the parties to form a coalition government in the interim period, were efficiently “spun” by the AK Party’s campaign for the November elections, which portrayed the party as the only realistic choice for economic stability in the country. In other words, the AK Party was the first, if not the only, choice for voters who wanted to see a functioning government, which for conjectural reasons, had to be a single party government. As the AK Party significantly increased its emphasis on the economy (and further, focused more on improving citizens’ individual economic situations and less on macroeconomic indicators), the economy is a significant explanatory factor for the party’s loss of votes in the June elections and for its comeback in the November elections.

With regard to the differences between the two elections in terms of the economy, it should be noted first, that the economy was a central issue of the June elections (especially for the opposition parties) whereas its primacy was shadowed by rising security and identity-related issues preceding the November elections.2 Second, while Turkey’s macroeconomic indicators were largely unpromising prior to the June elections, the growth rate rose higher than expected soon before the November elections. The growth figures, with the help of the AK Party and mainstream media’s presentation of them, revived the public’s optimism regarding the AK Party’s current economic performance.3

The final striking difference between these two elections with regard to the economy appeared in the electoral campaigns of the incumbent AK Party vis-à-vis the opposition parties. Prior to the June elections, the AK Party had resisted the appeal of the populist electoral promises of the opposition parties and, instead, had stressed financial discipline and budgetary concerns in its electoral campaign. In fact, the economy was not even at the center of the AK Party’s electoral campaign for the June elections, as the party emphasized other issues that were not directly within the realm of economics. Most prominent among the AK Party’s promises was the proposed shift to the presidential system from the country’s long-standing parliamentary system.4 Nevertheless, the party stayed quiet on this promise and turned back to the economy in its November electoral campaign. Moreover, the party even joined the opposition parties by not only stressing economic stability but also promising further redistributive policy changes that would favor low and middle income groups. I argue that these three differences between the June and November elections played a great role in the AK Party’s electoral victory in November.

The Picture of the Turkish Economy Before the June and November Elections Respectively

The economy seems to be among the main determinants of June 7 electoral results, if not the primary one. It seems that (a) the erosion of the post-2001 Turkish economic miracle in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, (b) the increasing emphasis of the opposition parties on the economy in their electoral campaigns, and in turn, (c) the electorate’s search for new alternatives to the AK Party to improve Turkey’s national and their own individual economic wellbeing significantly shaped the June 7 electoral results.

The post-2001 Turkish economy has often been referred to as a success story.5 While one side of this story has to do with the radical changes in the economic structure of the country, the other side involves giant public investments and social policies that favor greater numbers of citizens than ever before. With regard to the structural changes, the once-fragile banking system, which was one of the major reasons behind Turkey’s 2001 economic crisis, was reformed, together with the entire financial system of the country, after the AK Party assumed governance in late 2002.

While structural changes tend to be felt by the public over longer periods and only indirectly, the AK Party also carried out a number of policies that touched individual voters directly. A major example of these policies, as seen in Figure 1, was the expansion of social assistance programs both in kind and quantity during the AK Party years. Even the critics of AK Party’s social assistance programs, such as conditional cash transfers, acknowledge the role of such programs in diminishing poverty.6

Figure 1: Turkey’s Public Social Spending as a Proportion of its GDP7

With regard to public investments, particularly in the national infrastructure, the AK Party governments could reach millions of voters, as these investments became concrete evidence for the AK Party’s performance in the national development of the country. In the post-2002 period, Turkey’s highway network has increased by more than 15,000 kilometers; the number of airports has doubled to 50 in the country, and finally, “new, upscale housing complexes and shopping malls seem to flank every major city.”8

With regard to public investments, particularly in the national infrastructure, the AK Party governments could reach millions of voters, as these investments became concrete evidence for the AK Party’s performance in the national development of the country. In the post-2002 period, Turkey’s highway network has increased by more than 15,000 kilometers; the number of airports has doubled to 50 in the country, and finally, “new, upscale housing complexes and shopping malls seem to flank every major city.”8

The housing venture was particularly important amongst the infrastructure projects. According to the State Planning Organization,9 the construction sector, with over 200 sectors connected to it, is the locomotive engine of Turkey.10 Besides its macroeconomic role in pushing the growth rates up, the construction sector was also important for maintaining the AK Party’s electoral support base among low and middle income families. Turkey’s Housing Development Administration (TOKİ), which constructed 43,145 housing units in the 19 years prior to the AK Party’s rise to power in 2002, completed the construction of half a million houses from 2002 to 2011.11 Given that over 80 percent of TOKİ’s construction projects are designated for middle and low income groups with long-term, low-interest and affordable payment plans,12 the AK Party’s housing policy has benefited millions of people and had the chance of attracting those millions’ votes. The question thus becomes, why didn’t the positive electoral impact of these policies endure for the AK Party in the June 2015 elections?

Despite the AK Party’s longstanding social assistance programs and giant infrastructure and construction projects, the 2008 global financial crisis, the shortage of hot money to float to the developing world, and changing domestic parameters that raised questions about long-term stability in Turkey, gave rise to a number of concerns over the future of the Turkish economy. Turkey prior to the June elections seemed to be caught in the middle income trap like many other countries at its level of economic development.13Turkey could not escape from the global slowdown of growth rates in the post-2008 period; estimates anticipate a growth rate slightly over 3 percent for 2015.14 Given that the electorate tends to decide which party to vote for by looking at the recent past rather than contemplating longer periods, the 2015 growth data seems to be more striking when compared to the previous year. While Turkey’s growth rate was 4.87 percent in the first quarter (January-March) of 2014, the figure fell to 2.5 for the same period of 2015 just before the June elections.15 In other words, the overall electorate’s freshest memory of the country’s economic trajectory was filled with slowing growth rates, rather than the better growth figures of the preceding years. Even if growth rates seem to be abstract for ordinary citizens and many may not even follow the news on the recent growth data, the economic growth rate is palpable due to growing or shrinking industrial production, consumption, investments, etc. all of which make up the overall growth rate.

While the voters were not particularly satisfied before the June elections due to the reasons outlined above, the post-election period showed them that the economic future appeared likely to be much worse due to the inability of the parliament to form a coalition government

The slowing growth rate was not the only problematic indicator as the June elections approached. While Turkey’s gross domestic product per capita has hovered around $10,000 since 2010, the country’s unemployment rate raised to 11 percent, once again a double digit figure and inflation rate started to increase after years of low inflation under the consecutive AK Party governments.16 As shown in Table 1, such a picture brought about serious concerns in the eyes of the electorate –not just about the sustainability of Turkey’s economic development strategy with its three pillars (low interest rates, high-profile infrastructure projects, and speedy residential development)– but also about their own individual economic situations.17

Table 1: Turkey’s Annual Macroeconomic Indicators18

Such changes in the macroeconomic figures of the country had their microcosms in the daily lives of individual consumers, workers, and investors in Turkey. As the Adil Gür Research Company, which had the closest estimates of both the June and November electoral results, indicated months before the June elections, that the public’s response to the question “what is Turkey’s most important problem?” would be about 55 percent economy and poverty. Unemployment was the second most popular response, which was followed by the Kurdish question and terror. The same research also pointed out that the people’s perception of the AK Party’s success was on the decline.19 As the June 7 elections approached, the AK Party’s power of persuasion in the form of its economic promises had eroded in the eyes of some, if not many, voters. Economists estimated that the AK Party would be the central player in Turkish politics for another term, as long as a reasonably large portion of voters were satisfied with their economic condition.20While the voters were not particularly satisfied before the June elections due to the reasons outlined above, the post-election period showed them that the economic future appeared likely to be much worse due to the inability of the parliament to form a coalition government.

The general perception about the AK Party’s economic policy performance and the prospects of its alternatives changed in the aftermath of the June elections. As shown in Table 2, while the growth rate was as slow as 2.5 percent for the first quarter of 2015, the figure rose to 3.8 percent (0.7 points above expectations) in the second quarter. To many analysts’ surprise, the growth rate rose even higher and reached 4 percent in the third quarter (July-September). What made the third quarter results distinguishable is that while the growth rates of the first two quarters of 2015 were lower than the corresponding growth rates of the previous year, the third quarter’s growth in 2015 surpassed –in fact, more than doubled– the growth rate of the same time period one year ago. In accordance with the available research,21 this positive change in the growth figures, with its reflections in the daily lives of millions, seems likely to have rekindled the public’s hopes for the AK Party government’s economic performance once again.

Table 2: GDP Data in Quarters, 3rd Quarter: July-September 201522

The inability to form a coalition government after the June elections indicated another AK Party single party government as the only realistic solution to address the ongoing government problem

Another indicator of national economic performance is the current account deficit, which is the chronic problem of the country. Interestingly, the current account deficit figures were also in decline in the summer of 2015. Due to the falling rates of crude oil in the world markets and the shrinking cost of Turkish imports, the current account deficit data for the summer of 2015 came in smaller than the previous year’s figure.23 According to the Central Bank of Turkey’s data just before the elections, the current account deficit for October 2015 fell by 2.176 million USD compared to the same month of the previous year. As seen in Figure 2, Turkey’s current account deficit narrowed to 5.44 percent of gross domestic product in the third quarter of 2015. The figure was 5.74 in the previous quarter of 2015, and it was 5.91 in the same quarter of the previous year. Nevertheless, it should be stated that such a minor improvement in the current account balance of the country is far from a remedy to the country’s longstanding current account deficit problem.

Figure 2: Turkey’s Current Account Deficit to its GDP24

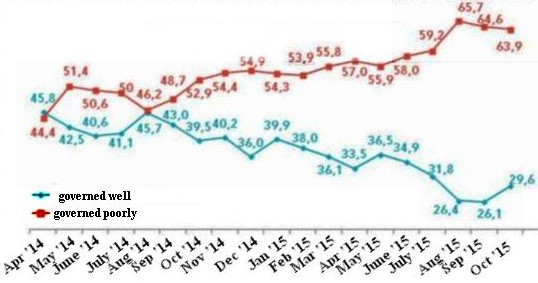

It seems that despite the speedy depreciation of the Turkish lira vis-à-vis the USD and Euro between the June and November elections (shown below in Figure 4),25 lack of a significant improvement in current account balance,26 and other major figures from the steady unemployment problem to inflationary pressures, particularly the increasing growth rates consecutively in each quarter of 2015, once again, made the AK Party a credible and capable economic policy maker in the eyes of the electorate. As shown in Figure 3, the public’s general opinion about the AK Party government’s economic policy performance was in decline prior to the June elections, whereas the general opinion about the AK Party-led interim government’s economic policy performance was on the rise as the November elections were approaching.

While the AK Party kept its promises within a reasonable range, the opposition parties were quite enthusiastic about promising big increases to the minimum wage and other social and economic benefits

Figure 3: “Do You Think the Economy is Recently Governed Well or Poorly?” Overtime Graph for April 2014-October 201527

It seems probable that the electorate saw the AK Party as the planner of the success in matters such as economic growth, while viewing the opposition parties as responsible for failure in matters such as the depreciation of the Turkish lira during the five-month period between the June and the November elections. Why the AK Party got the credit for the good indicators such as economic growth, and the opposition parties got the blame for poor indicators such the falling rate of the Turkish lira (shown in Figure 4) is a major sign of success for the AK Party’s electoral campaign strategy. The inability to form a coalition government after the June elections indicated another AK Party single party government as the only realistic solution to address the ongoing government problem. Such a situation fit perfectly with the AK Party’s electoral campaign, which portrayed the party as the only capable actor to settle and maintain economic and political stability in the country.

Figure 4: 2015 USD/TL Parity with Post-election Days of June and

November Elections Specified28

The Economic Policy Promises of Effective Political Parties in Their 2015 Electoral Campaigns

The economy was a major battle zone of electoral competition preceding the June 7 elections. All the major parties dedicated a great amount of airtime to economic issues in their election declarations, their statements to the press, in their speeches to the masses during electoral rallies, and in their various written or visual campaign tools. The main controversy with regard to the economy during the campaigns for the June elections occurred between the incumbent AK Party and the opposition parties. On the one hand, the AK Party stressed that the economy was on good terms and that the country needed another term of single party rule for the endurance of political and economic stability, which was allegedly the necessary condition for economic progress. On the other hand, the opposition parties throughout their electoral campaigns argued that the overall economic performance of the country was in decline and needed a radical transformation and reform process to be led and governed by a new government with a fresh perspective on economic matters. In a nutshell, the incumbent and opposition parties depicted two radically different pictures of the country’s economic situation.

Another difference between the incumbent AK Party and the opposition parties has to do with their attitudes with regard to so-called economic populism. While the AK Party kept its promises within a reasonable range, the opposition parties were quite enthusiastic about promising big increases to the minimum wage and other social and economic benefits (to be discussed below) that would affect a great portion of the society.

Another difference between the AK Party and the opposition parties involves their prioritazion of different economic issues. While the AK Party stressed continuing large-scale infrastructure investments, the opposition parties emphasized the allegations against the government such as corruption and misuse of public resources. This brings us to an anomaly with regard to the electoral campaigns of the opposition parties. While the opposition parties fundamentally differed and disagreed in all policy areas, from the identity question to foreign policy,29 they were quite in agreement with regard to their proposed economy agendas. Both the content and the tone of the opposition parties were quite similar in terms of their economy-related promises.

The AK Party presented its 63-page long economic program for the June elections under the title of “Stable and Strong Economy - İstikrarlı ve Güçlü Ekonomi,” which was the election motto of the party. The party placed the notion of stability at the center of its entire electoral campaign and promised continuing economic stability, growth, and further investments in large scale infrastructure projects from gigantic new airports, to bridges to connect Asia and Europe. The party’s main strategy was to remind the electorate how bad the overall economy had been, prior to the AK Party years. Both the public statements of AK Party politicians and the campaign tools of the party stressed extremely high inflation (shown in Figure 5) and interest rates, and the poor infrastructure of the years preceding AK Party rule.

Figure 5: Real and Projected Inflation Data during the AK Party Years30

Given the post-2008 Turkish economy’s loss of its miraculous achievements with the decreasing growth rates, fluctuations in inflation and unemployment rates, the erosion of the Turkish lira with respect to the USD and Euro, and the high current account deficit, the AK Party also felt the necessity to promise the electorate further structural reforms to overcome the emerging and fast-growing economic problems of the country. One such goal was to increase the share of the production and manufacturing sector in the overall GDP and, in turn, decrease the country’s dependency on imported products. As the inflation rates once again reached double digit numbers, the AK Party promised to stick to stable monetary policies to deal with the relatively high inflation rates compared to the inflation targets. As a direct result of Turkey’s increasing imports, the current account deficit has been the biggest challenge to the consecutive AK Party governments since 2002. Therefore, in addition to increasing local production, the party also promised to develop measures to increase the saving rates within the country in order to deal with the current account deficit problem.

With the June elections, for the first time, the opposition parties stopped focusing on “fictitious” and abstract discussions around the future of laicism in Turkey. Instead they focused on positive messages mostly in the realm of the economy

While the AK Party acknowledged the deep problems of the economy, such as the current account deficit, and stressed the need for boosting local production and creating internationally recognized brands, placed less emphasis on problems related to the distribution of existing wealth, which was at the center of the opposition parties’ electoral campaigns. While criticizing the AK Party government’s alleged mismanagement of macroeconomic matters, the opposition parties paid much greater attention to the question of distribution. One prominent example of this division between the incumbent and opposition parties involves the promises given with regard to the minimal wage. The CHP, the MHP, and the HDP, all promised to make big increases to the minimum wage. While the MHP promised 1400 TL as the new monthly minimum wage if they were to take over the government, the CHP increased the bid to 1500 TL and the HDP to 1800 TL in their electoral declarations for the June elections.

The opposition parties also addressed another widely-known problem of the Turkish economy: the growing number of contract workers who are employed by sub-employers and have no long-term job security, employer paid health insurance, or pension guarantee. The number of contract workers is declared to be 1 million 300 thousand31 and the real figures are estimated to be even larger than what the official numbers indicate. All three major opposition parties promised the electorate to end the contract workers’ system. They all promised to provide contract workers with job security and social security with the provision of long-term positions starting with public jobs.32 The opposition parties gave further promises to greater masses from expanded conditional cash transfers to the elderly, students, and low and no income families, to subsidized fuel for the agriculture sector. In fact, such redistributive policies and other assistance programs to the low and middle income groups tremendously increased both in size and kind during the AK Party years,33 but the opposition parties further promised to increase the amount and kinds of the aid and also to establish a universal assistance program, which, they promised, would be entirely need-based and free from any kind of bias or vote-buying.

The AK Party, during its campaign for the June elections, called the critiques and electoral promises of the opposition parties populist, and presented itself as a disciplined, serious, and responsible party that does not pursue short-term electoral policies over long-term national economic interests. The party politicians and former party leader President Erdoğan often stated that the opposition parties know that they cannot win the elections and take over the government, therefore they feel free to be quite generous in their electoral promises.34 In its election declarations, the AK Party made it clear that “we have never pursued populism in the economy and will never do so. We will not deviate from fiscal discipline and will implement our monetary policies decisively.”

In the June elections, the opposition parties, CHP, HDP, and MHP, all included significant names in their candidates list, indicating who would take charge of the economy, should they win the elections and form the next government.35 With the June elections, for the first time, the opposition parties stopped focusing on “fictitious” and abstract discussions around the future of laicism in Turkey. Instead they focused on positive messages mostly in the realm of the economy. The most prominent amongst those was the CHP’s ‘Center Turkey Project,’ which aimed to build a “mega city” in Central Anatolia between 2020 and 2035 to serve as an international production and logistics center. According to the CHP program, this project would contribute to the Turkish economy with a value of 147 billion USD annually and create 2.2 million new jobs in the country.36

A shift toward the economy with more positive messages and greater promises became a major factor in the AK Party’s electoral victory in November

Millions of voters turned away from the incumbent AK Party and toward the opposition parties because of their positive economic messages and generous economic promises to individual voters in the June elections. Following its disappointment with the June results, the AK Party radically changed its campaign strategy. With such a lesson in mind, the AK Party redirected its November electoral campaign and increased the tone of positive economic messages and relevant promises for individual voters for the November elections. The most concrete example of this shift can be seen in the AK Party’s promises regarding the minimum wage. While the party did not join the opposition parties in their bid to increase the minimum wage in its June campaign, and in fact blamed them for being populist, it did promise to increase the minimum wage to 1300 TL in its November campaign.37 The party also targeted young voters, who are the primary victims of the surge to double-digit unemployment rates. Given that the AK Party was not successful in attracting young voters compared to the other parties in the June elections, the party paid greater attention to young voters during its November elections campaign.38 The AK Party promised to support young entrepreneurs by providing them unconditional credit for their projects. Soon before the November elections, party leader and Prime Minister Davutoğlu also stated that his party would increase scholarships for the students and erase the general health insurance debts (genel sağlık sigortası) of unemployed young people. Such promises are seen as the party’s greatest economic promises in its history.39

In a nutshell, as shown in Table 3, the AK Party took a lesson from the June electoral results and found its economic promises for the June elections weak. In its November campaign, the party dropped its emphasis on grand political projects, such as a shift to the presidential system, from its electoral campaign. The party stressed financial and budgetary discipline less, and made more generous promises. Such a shift toward the economy with more positive messages and greater promises became a major factor in the AK Party’s electoral victory in November.

Table 3: The Differences Between the Incumbent AK Party’s and the Opposition

Parties’ Economic Promises in the June 7 and November 1 Elections

The Effect of the Economy on the Electoral Results

The June 7 elections were arguably affected by the economy to a greater extent than previous elections.40 In fact, to nobody’s surprise, electoral results are often heavily determined by the overall economic situation of the country; the economy is even argued to determine the electoral results with almost mathematical precision.41 When the AK Party first came to power as a newly-formed fresh party in the aftermath of the November 2002 elections, the severe economic crisis of the previous year had swept away the major parties of the previous coalition government by leaving the Democratic Leftist Party (DSP), the MHP, and the Motherland Party (ANAP) under the 10 percent electoral threshold and hence out of parliament. As argued by Çarkoğlu and Yıldırım,42 public evaluations concerning the economic policy performance of the AK Party remained steadily high and even improved over time, which led to the party’s increasing electoral support during its successive electoral victories.

The positively changing economic figures, particularly the increasing economic growth rate, together with the AK Party’s turn to the economy in its electoral promises led the voters to turn their faces to the AK Party once again in the November elections

Turkey’s next major economic crisis, which occurred in 2008 and this time was global in scale, led the AK Party’s votes to drop to 38.39 percent with a 3.5 point loss in the 2009 local elections. A severe shake to the Turkish economy in the following years made a similar loss inevitable for the 2015 elections. According to Çarkoğlu and Aytaç’s survey research,43 56 percent of the electorate thought the economy was the most important problem of the country. While the economy has always been a concern for the electorate, an even more important finding of this study tells us what distinguishes the June 7 elections from the previous elections with regard to the electorate’s attitude about the economy and political parties. Accordingly, while in previous elections the electorate thought that only the incumbent AK Party could help mitigate the deep economic problems of the country, this time the opposition parties were more strongly viewed as the solution for Turkey’s economic problems.

According to the major public polls, the Turkish electorate felt a downward trend in their individual economic situations, and consumer confidence levels continued to fall in the last five months preceding the June 7 elections.44 In their analysis of the local and parliamentary elections from 1950 to 2004, Akarca and Tansel conclude that Turkish voters take the government’s economic policy performance into account but do not look back beyond one year.45 Apparently this finding proves true for the June 7 elections as well.

As discussed above, the growth data improved in the third quarter and its impact was felt in daily economic encounters. Such a positive change seems to have played an important role for the AK Party’s comeback in the November elections. But even more importantly, the interim period between the two elections, with its increasing terror attacks, failure to form a coalition government, and boiling international politics, increased the public’s doubts about the future of the Turkish economy if the AK Party could not form a single party government.

Conclusion

This article has outlined the economic context of the June and November general elections based on a descriptive analysis of the macro-economic indicators, an analysis of the major parties’ electoral strategies with regard to the economy, and insights from the public poll data on people’s economic expectations. Hence, the article has attempted to outline the economic context of the two elections without falling into the trap of economic reductionism.

In the light of the discussion in this article, it can be concluded that the downward trend in some economic indicators prior to the June elections led millions of voters to turn their preferences away from the incumbent AK Party toward the opposition parties. The opposition parties focused on the economy more than they did in the past, not only criticizing the government but also stressing their own economic agendas, and sending positive messages to the electorate in their June electoral campaigns. As the elections of November were approaching, it seemed that all was quiet on the economic front. While the Turkish lira continued to sink to a record low against the USD and the Euro, the economy seemed to be far from the front pages of the papers. The PKK ending of the two and half year ceasefire and the rising conflict between the state security forces and the PKK silenced the economy debates. Nevertheless, the electorate seemed to need a strong government in such a shaky environment to keep the economy on a good or at least steady track. The positively changing economic figures, particularly the increasing economic growth rate, together with the AK Party’s turn to the economy –not only in terms of macro-economic policy promises but also in economic policy suggestions that directly touch individual citizens’ lives– in its electoral promises led the voters to turn their faces to the AK Party once again in the November elections.

Endnotes

- That being said, the party’s electoral victories were only easy in terms of the electoral results vis-a-vis the other parties. During and in the aftermath of the electoral processes, on the other hand, the party had pretty tough times. It once even came close to being banned by the Constitutional Court in 2008 and escaped that fate by only one vote in the Constitutional Court (5 members of the 11-member Court voted for the closure). For a discussion of the AK Party’s dominant party role, see M. Müftüler-Bac and F. Keyman, “The Era of Dominant-Party Politics,” Journal of Democracy, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2012), pp. 85-99; and H. Ete, M. Altınoğlu, and G. Dalay, “Turkey under the AK Party Rule: From Dominant Party Politics to the Dominant Party System,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 17, No. 4 (2015).

- For a detailed analysis of the differences between the two elections with regard to the identity question, see T. Köse, “Kurds, Alevis and Conservative Nationalists: Identity Dynamics of the June and November 2015 General Elections of Turkey,” Insight Turkey,Vol. 17, No. 4, (2015).

- For instance, Ali Babacan, who was in charge of the economy during most of the AK Party years after 2002, stressed that the political uncertainty after the June elections was influencing Turkey negatively but as the November elections came closer, the economy improved again under the AK Party-led interim government. He explained this improvement with reference to the general expectations about the stabilizing effect of the upcoming November electoral results. See “Babacan: Son Bir Ayda Pozitif Ayrıştık,” Habertürk, (27 October 2015), retrieved 27 December 2015, from http://www.haberturk.com/

ekonomi/borsa/haber/1145358- babacan-son-1-ayda-pozitif- ayristik. - Even if it is commonly called a parliamentary system, in fact, Turkey’s current system seems to be closer to a semi-presidential one, as argued by E. Özbudun “Presidentialism vs. Parliamentarism in Turkey,” Policy Brief 1, (2012).

- For instance, amongst many others, economist Taner Berksoy calls Turkey’s post-2001 economic trajectory, particularly with respect to its position vis-à-vis the IMF, a “rare success story.” See “Turkey as

a ‘Success Story for the Troubled IMF,” Hurriyet Daily News, (27 December 2015), retrieved 27 December

2015 from http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkey-a-success-story- for-the-troubled-imf.aspx?page

ID=238&nid=47180. Economy analyst Alexandra Jarosiewicz, while cautioning about the future trajectory, acknowledges that “Turkey’s economy has become synonymous with success and well-implemented reforms.” See, “Turkey’s Economy: A Story of Success with an Uncertain Future,” OSW, 6 November 2013, retrieved 27 December 2015 from http://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/osw-commentary/ 2013-11-06/turkeys-economy-a- story-success-uncertain-future . The post-2001 economic miracle started with Kemal Derviş’s policies prior to the AK Party rule and is developed further by the AK Party after the 3 November 2002 elections. - Critics focus on concerns about the rise of possible clientalistic linkages, such programs’ instrumental role in bolstering conservative social policies, particularly about approved gender roles and regional imbalances. For an evaluation and critical perspective on conditional cash transfers in Turkey, see C. Bergman and M. Tafolar, “Combating Social Inequalities in Turkey through Conditional Cash Transfers (CCT)?” Paper submitted for the 9th Global Labour University Conference, Inequality within and among Nations: Causes, Effects, and Responses, 15. -17.05.2014, Berlin School of Economics and Law, available at http://www.global-labour-

university.org/fileadmin/GLU_ conference_2014/papers/ Bergmann_Tafolar.pdf, retrieved 25 December 2015; and A.Y. Elveren and S. Dedeoğlu, 2000’ler Türkiye’sinde Sosyal Politika ve Toplumsal Cinsiyet [Social Policy and Gender in Turkey in the 2000s], (İstanbul: İmge Kitabevi Yayınları, 2015). - Social Expenditure Database (SOCX), OECD, available from http://www.oecd.org/social/

expenditure.htm, retrieved 3 January 2016. - Daniel Dombey, “Six Markets to Watch: Turkey,” Foreign Affairs, Vol. 11, (11 August 2015), retrieved 24 December 2015 from https://www.foreignaffairs.

com/articles/turkey/2013-12- 06/six-markets-watch-

turkey. - DPT- Devlet Planlama Teşkilatı, “Dokuzuncu Kalkınma Planı, 2007-2013: İnşaat, Mühendislik - Mimarlık, Teknik Müşavirlik ve Müteahhitlik Hizmetleri Özel İhtisas Komisyonu Raporu,” Yayın, No: 2751, ÖİK: 698, (Ankara: DPT, 2007).

- For a critical perspective on this construction-led approach, see O. Balaban, “The negative effects of the construction boom on urban planning and the environment in Turkey: Unraveling the role of the public sector,” Habitat International, Vol. 36, No. 1 (2012), pp. 26-35.

- For the data, see: http://www.toki.gov.tr/

kurulus-ve-tarihce, retrieved 14 December 2015. - See: http://www.toki.gov.tr/

AppResources/UserFiles/files/ FaaliyetOzeti/ozet.pdf, retrieved 14 December 2015. - The middle-income trap, according to Breda Griffith. See, “Middle-income Trap,” Frontiers in Development Policy, Raj Nallari, Shahid Yusuf, Breda Griffith, Rwitwika Bhattacharya (Eds.), World Bank, 2011, pp. 39-43. Here, Breda refers to a situation whereby a middle-income country fails to accomplish its transition to a high-income economy due to reasons such as rising costs and declining competitiveness. For a discussion of the middle income trap, see S. Aiyar, et al. “Growth Slowdowns and the Middle-income Trap,” International Monetary Fund Working Papers, No. 13-71, (2013); and H. Kharas and H. Kohli, “What Is the Middle Income Trap, Why Do Countries Fall into It, and How Can It Be Avoided?,” Global Journal of Emerging Market Economies, Vol. 3, No. 3 (2011), pp. 281-289.

- The IMF has dropped its estimates for Turkey’s growth rate in 2015 from 3.4 to 3.1. See http://www.bloomberght.com/

haberler/haber/1763983-imf- turkiyenin-2015-buyume- tahminini-dusurdu, retrieved 11 August 2015. - http://www.tuik.gov.tr/

PreHaberBultenleri.do?id=18728 , retrieved 11 December 2015. - The inflation rate of 6.16 percent in 2012 was the lowest inflation rate in Turkey since 1968.

- For the numbers, see D. Dombey, “Turkey: A Flagging Growth Story,” Financial Times, 18 May

2015, available at http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/692061c0-f988-11e4-ae65- 00144feab7de.html#axzz3i

W6zg2gK, retrieved 11 August 2015. - Adapted from M. Eğilmez, 2015, “AKP’nin Ekonomide 12 Yılı,” retrieved 23 December 2015 from http://www.mahfiegilmez.com/

2015/04/akpnin-ekonomide-13- yl.html. Inflation data corrected with the TCMB data on http://www.tcmb.gov.tr/wps/ wcm/connect/efc2fbcc-ca6e- 4573-9f90-4d7a13fa1f45/ RemarksG09_12_2015.pdf?MOD= AJPERES, retrieved 24 December 2015. Bold rows indicate the parliamentary election year. - http://www.internethaber.com/

sonuclari-bilen-adam-adil- gurden-muthis-tahminler- 751724h.htm, retrieved 15 December 2015. - Cem Başlevent and Hasan Kirmanoğlu, “Economic Voting in Turkey: Perceptions, Expectations, and the Party Choice,” Research and Policy on Turkey, Vol. 1, No. 1 (2015).

- For instance, Ali Akarca argues that voters place more weight on growth than inflation in their voting decisions. See, A. Akarca, “Inter-election vote swings for the Turkish ruling party: The impact of economic performance and other factors,” Equilibrium, Vol. 6, No. 3 (2011), pp. 7-25.

- Turkish Statistical Institute, Data on Gross Domestic Product, III. Quarter 2015. See: http://www.tuik.gov.tr/

PdfGetir.do?id=18730, retrived on 14 December 2015. - According to the Central Bank data for October 2015, just before the elections, the deficit for October 2015 fell by 2.176 million USD compared to the same month of the previous year.

- Translated from the Central Bank of Turkey figure available at http://www.tcmb.gov.tr/wps/

wcm/connect/TCMB+TR/TCMB+TR/ Main+Menu/Para+Politikasi/ Interaktif+Grafikler/Cari+ islemler+dengesi. - The USD/TL parity rose from 2.75 on the election day of June 7 to 2.85 on the election day of November 1st. It was highest on September 14th with a value of 3.06.

- Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey Report. See: http://www.tcmb.gov.tr/wps/

wcm/connect/

8ae2c7c6-bea2-4bbf-9a9f-2ce620d011df/ODRapor_20152. pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CACHEID= ROOTWORKSPACE8ae2c7c6-bea2- 4bbf-9a9f-2ce620d011df, retrieved 14 December 2015. - Translated from Metropoll Research Company’s public poll figure, available at https://pbs.twimg.com/media/

CRa6pSgU8AI-51r.jpg. - Adapted from Bloomberg’s 2015 USD/TL parity table with minor modifications. See Bloomberg, (23 December 2015), retrieved 23 December 2015 from http://www.bloomberg.com/

quote/USDTRY:CUR. - For the CHP, see Yusuf Gökmen and Tanju Tosun, “November 1 Elections and CHP : An Evaluation on Political Deadlock,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 17, No. 4 (2015); for the MHP, see Şükrü Balcı and Onur Bekiroğlu, “The Nationalist Action Party (MHP) in the General and Early Elections on June 7 and 1 November, 2015,” Insight Turkey Vol. 17, No. 4 (2015); for the HDP, see Vahap Coşkun,, “HDP Torn Between Violence and Politics,” Insight Turkey Vol. 17, No. 4 (2015); For a comparison of all the major competing parties in the June and November elections with regard to their take on the identity question during the electoral process, see Köse (2015).

- See http://www.tcmb.gov.tr/wps/

wcm/connect/efc2fbcc-ca6e- 4573-9f90-4d7a13fa1f45/ RemarksG

09_12_2015.pdf?MOD=AJPERES, retrieved 14 December 2015. - As of July 2014, the Minister of Labor and Social Security Faruk Çelik declared the total number of contract workers to be 1.361.673. Accordingly, while over 755 thousand of those workers are employed in the public sector, over 606 thousand are employed in the private sector. See http://www.milliyet.com.tr/1-

36-milyon-taseron-calisiyor- gundem-1975085/, retrieved 11 August 2015. - This promise can be seen in the election declarations of the respective parties, e.g., CHP June 2015 election declaration, p. 77; MHP June 2015 election declaration, p. 83; HDP June 2015 election declaration, p. 35.

- Social spending rose from 1,376 TL in 2002 to 18,216 TL in 2011 during the AK Party years. See

UNICEF, “Turkey Office Social Policy Unit, Policiy Paper on Improving Conditional Cash Transfers

Programme in Turkey,” (2014), Policy paper available at http://sosyalyardimlar.aile.gov.tr/data/

5429198a369dc32358ee29b9/Policy_Paper_on_Improving_ Conditional_Cash_Transfers_ Programme_in_Turkey.pdf, retrieved 24 December 2015. For a contrary perspective of the Turkish welfare system critisizing the commodification of the system, see Şule Şahin and Adem Y. Elveren, “Gender Gaps in the Individual Pension System in Turkey,” in Saniye Dedeoglu and AdemYavuz Elveren, eds. Gender and Society in Turkey:The Impact of Neoliberal Policies, Political Islam and EU Accession. Vol. 4, (IB Tauris, 2012). - Source: http://haber.stargundem.com/

siyaset/1473753-kuru-siki- atip-tutuyor.html, retrieved 11 August 2015. - For example, the CHP nominated Selin Sayek Böke, who was the head of the Economics Department at Bilkent University and had worked with the IMF as an economist and served the World Bank as a consultant. The MHP also nominated an important economy figure in the June elections. The MHP’s Uşak candidate Durmuş Yılmaz was the former head of the Central Bank of Turkey. The HDP’s economy figures, on the other hand, were mostly union leaders and union representatives. The AK Party increased the number of its prominent economy figures in the November elections. Most prominent among them was Ali Babacan, who was primarily in charge of the economy during the consecutive AK Party government years from 2002 to 2015, but was not nominated in the June elections due to the party’s three-term limit for its deputies. Babacan’s joining with other prominent economy figures such as Mehmet Şimşek and İbrahim Turhan significantly increased the AK Party’s image with regard to its economic policy capabilities. For a sample of international investors’ positive comments on Babacan’s return, see Isobel Finkel and Onur Ant, “Routed by Market, Turkey Puts Ousted Policy Guru Back on Bench,” Washington Post, (22 September 2015).

- For a discussion of the CHP’s positive economy messages in the June elections, see E. A. Bekaroğlu, “7 Haziran Seçimlerinde CHP: Sosyal Demokrat Popülizm?,” in Araftaki Seçim: Türkiye’de Siyasi Partiler ve Seçim Kampanyaları, edited by E. A. Bekaroğlu, (İstanbul: Vadi, 2015), pp. 107-158.

- AK Parti 1 Kasım 2015 Genel Seçimleri Seçim Beyannamesi: Huzur ve İstikrarla Türkiye’nin Yol Haritası, p. 115.

- More than a quarter of the MHP and HDP voters in the June elections were between the ages of 18 and 28. This age-group’s support for the AK Party was 5 points lower than the party’s vote share. While

AK Party’s voters over the age of 44 constituted 43 percent of the party’s votes, the same ratio was only 31 percent for the MHP and HDP. See, “7 Haziran Sandık ve Seçmen Analizi,” KONDA, (18 June 2015), p. 61. - For example, the popular news portal T24 used this phrase in its headline: “AKP, Tarihinin en Büyük Ekonomik Vaatlerini 1 Kasım için Yaptı.” See T24, (4 October 2015), retrieved 23 December 2015 from http://t24.com.tr/haber/

akpnin-secim-beyannamesi- bugun-aciklaniyor,311746. - Erdal Tanas Karagöl and Nergis Dama, “Partilerin Vaatleri Seçim Sonuçlarını Nasıl Etkiler?,” SETA, (2015).

- Ali T. Akarca, “Analysis of the 2009 Turkish Election Results from an Economic Voting Perspective,” European Research Studies Journal, Vol. 13, No. 3 (2010), pp. 3-38; Ali T. Akarca and Aysit Tansel, “Social and Economic Determinants of Turkish Voter Choice in the 1995 Parliamentary Election,” Electoral Studies, Vol. 26, No. 3 (2007), pp. 633-647.

- Ali Çarkoğlu and Kerem Yıldırım “Election Storm in Turkey: What do the Results of June and November 2015 Elections Tell Us?” Insight Turkey, Vol. 17, No. 4 (2015).

- Ali Çarkoğlu and Selim Aytaç, “Public Opinion Dynamics Towards June 2015 Elections in Turkey,” http://www.aciktoplumvakfi.

org.tr/turkiye_kamuoyu_ arastirmasi2015.php. - “Yavaşlayan Ekonomik Büyüme Seçmeni Etkiler Mi?,” BBC, (29 May 2015), retrieved 11 August 2015 from http://www.bbc.com/turkce/

ekonomi/2015/05/150529_secim_ ekonomi_gs2015. - Ali T. Akarca and Aysit Tansel, “Economic Performance and Political Outcomes: An Analysis of the Turkish Parliamentary and Local Election Results Between 1950 and 2004,” Public Choice Vol. 129, No. 1-2 (2006), pp. 77-105.