Anybody visiting or living in Istanbul, Antalya and certain other places in Turkey will recognize the visible presence of foreigners – e.g., Saudi shoppers, Western business people, African street vendors and Syrian refugees – some of whom do not just visit but also live and work in Turkey. In literature and the media, there are references to German, Dutch, British or Swedish retirees, Russian and Ukrainian businessmen and women, Georgian construction workers, Armenian nannies, Moldovan domestic workers and caretakers, Uzbeks and Kirgiz workers, Nigerian street vendors, African football players, Syrian gardeners, Afghans, Egyptian and Somali shop owners or Azerbaijani and other students. A World Bank report even suggests that at some point after 2007, Turkey – after decades of being a sending country for labor migrants and refugees –became a net immigration country, hosting a comparably small but increasing number of immigrants plus a significant number of refugees. This implies that Turkey, fuelled by economic growth and relative political stability, went through a migration transition from an emigration to an immigration country. Academics were the first to highlight these developments;1 meanwhile, this became widely acknowledged in Turkish policy circles.2 However, the Turkish public is probably less aware of this shift and Western observers are still largely concerned with Turkey’s image as an emigration country. In any case, this paradigm shift is of enormous social, economic and political relevance and is of historical significance.

For Turkey, the increasing international mobility and immigration of non-ethnic Turks or non-Muslims represents a new cultural and political challenge, which requires a fresh approach to studying Turkey and migration as well as innovative political responses. Notably for ‘the West’ and in particular the EU, it is time to rectify the ever more inappropriate perception of Turkey as an emigration country and reconsider the long-lasting fear of a potential ‘flood’ of Turkish migrants. Assessing Turkey’s actual migration situation is thus not only an academic exercise, but also a politically relevant undertaking that contributes to the knowledge base of Turkish domestic politics and clarifies Turkey’s position in the global migration order, which should be relevant to the international relations stakeholder.

During Ottoman times, the Ottoman Empire was a space of migration within the empire as well as of immigration from more distant regions; the arrival of Polish, Spanish, Jewish or Tatar migrants and refugees are only the most prominent examples

This paper thus sets out to explore the level and diversity of immigration to Turkey, notably that of non-ethnic Turks. It also considers some of the socio-politico-economic discrepancies between Turkey, its neighbors and major migrant-sending countries that are usually understood as drivers of migration.

Immigration to Turkey

Modern migration in the territory that is now Turkey went through four historical stages. During Ottoman times, the Ottoman Empire was a space of migration within the empire as well as of immigration from more distant regions; the arrival of Polish, Spanish, Jewish or Tatar migrants and refugees are only the most prominent examples.3 In the early to mid-20th century, during the break-up of the Ottoman Empire and the founding of the Republic of Turkey, it was an immigration country fuelled by population exchanges mostly with Greece and then the immigration of ethnic Turks from other parts of the former empire. From the 1960s to the 1990s, movements in Turkey were dominated by emigration, first of labor migration to the EU which ended in the early 1970s and later the Gulf countries, among others. Although labor emigration continues today, for example, to North Africa or Russia, it is now down to only a few ten thousand. Second, after the 1970s, the so-called guest-worker emigration was followed by family-related emigration, which also continues today, though on lower levels. Third, there was then also forced migration of refugees, but this faded out by the early 2000s. Finally, during the late 20th century, the country slowly turned into an immigration country again.

“Immigration has been an essential and constitutive element since the early days of Turkey’s existence as a nation-state, with international migration to Turkey being almost exclusively constituted of ethnic-Turkish population from bordering countries.”4

The recent period of immigration to Turkey still includes ethnic Turks, either first generation returnees or second generation ethnic Turks from Germany and other so-called guest-worker countries. It is estimated that from the early 1920s to late 1990s, 1.7 million ethnic Turkish Muslims, mostly from the Balkans, moved to Turkey.5 This included 200,000 Turks and Pomaks who were expelled from Bulgaria in 1989 (another 100,000 eventually returned to Bulgaria). In addition, a large portion of the 38,000 Muslim refugees that arrived in the mid to late-1990s from Bosnia and Kosovo and the 17,000 or so Ahiska or Meskhetian Turks from various parts of the former Soviet Union stayed in Turkey.6 Finally, during the emigration period, Turks also returned to Turkey, sometimes after having spent many years abroad. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, an average of 45,000 Turks returned annually from Germany, which dropped to just over 35,000 during the 2000s.7 In recent years, this has also included ethnic Turks who hold foreign nationalities and were born or spent most their lives in other countries. The majority of these more recent ethnic migrants or returnees are 25 to 50 years old and thus still economically active.8 However, the recent period is also characterized by an increasing number of non-ethnic Turkish and/or non-Muslim immigrants arriving in Turkey for various purposes, such as business, employment, education, recreation, retirement and international protection. This paper mainly deals with this category of international, non-ethnic Turkish immigrants.

In migration studies, a distinction is made between flows, inflows and outflows, and migrant stock, meaning the number of foreign-born migrants who reside in a given country. However, national and local data on flows and immigration to Turkey is imprecise and incomplete. The Turkish Statistics Institute (TurkStat) explains that “flow data, immigration and emigration statistics cannot be produced from ABPRS [addressed-based registry] or any other administrative data sources.”9 This is partly due to insufficient record-taking but also to migrants’ often irregular strategies which hinders effective monitoring. Furthermore, “settled foreigners [did] not acquire a residence permit. They can choose to stay in the country having just a tourist visa and it [was] easy to extend the duration of this visa.”10 They are thus not recorded as de facto immigrants but as tourists. The new Law on Foreigners and International Protection (2013) is going to change this and thus will contribute to better statistics. Nevertheless, implementation will take time.

Illegal immigrants are escorted by the officers of Turkey’s Coast Guard Mediterranean Region Command

Illegal immigrants are escorted by the officers of Turkey’s Coast Guard Mediterranean Region Command

as they arrive in Mersin, Turkey on December 06, 2014. | Turkish Coast Guard Command / Anadolu Agency

Migration Flows

The travel of foreigners to and from Turkey has almost tripled over the last decade, from 23 million arrivals and departures in 2001 to around 63 million in 2011; in addition, Turkish citizens made a recorded 23 million journeys. Mobility to and from Turkey increased across all countries, whether it is from or to the UK, Ukraine or South Korea. However, flows from Germany are the highest, with 9.5 million movements, while citizens from Britain, the Netherlands and France account for 5 million, 2.4 million and 2.2 million travelers, respectively. Travel to and from the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) has quadrupled to almost 13 million visitors, while another 5 million from Asian countries, 4 million from the Middle East and Gulf countries, 1.5 million from the U.S. and .9 million from African countries were recorded. Notably flows from Russia have almost quintupled from just 1.5 million in 2001 to almost 7 million in 2011. Indeed, Russia is now the second most important country of origin of travelers. Flows from China have also quadrupled, although it remains low (192,000).11

In contrast, in 2000, there were only 234,111 immigrants in Turkey according to TurkStat, while TurkStat recorded 776,000 foreign-born people in the 2011 Population and Household Survey

A small proportion of these flows represent emigrants from and immigrants to Turkey. According to the World Bank, net immigration – the balance between emigration and immigration - between 2009 and 2013 was +350,000 and up from -50,000 in 2007.12 This suggests that on average 70,000 more people per year immigrated than emigrated. For instance, in 2010, net immigration was supposed to be 62,000, a number that includes work permits holders (11,800 in 2011) and 8,400 new foreign students.13 On the other hand, by the early 2000s, there were fewer than 50,000 people, one-third of which was family-related migration, while the others were students or workers who went to the European Union. In 2011, another 53,800 mostly temporary labor migrants were officially recorded by the Turkish Employment Office (IŞKUR).14 From these numbers, it can be calculated that at least 175,000 people annually enter Turkey to stay for longer periods of time, outnumbering emigration and turning Turkey’s migration balance positive. Other sources claim that even up to “250,000 people …enter Turkey each year with the intention of staying longer, be it for education, employment, or retirement.”15 Finally, there is some overlap between short-term visits on tourist and labor visas and other forms of migration: some short-term visits, notably from CIS countries but also from Africa, are actually one-off or repeated entries for economic purposes, either for suitcase trade or for short-term or seasonal employment, and can subsequently lead to longer stays. Short-term visits can also disguise transnational practices where the traveler actually lives or pursues economic activities in two countries and is thus not a mere visitor.

A specific flow consists of migrants who enter Turkey legally or clandestinely with the intention to move on to an EU country, denoted as transit migrants. However, whilst intending to move on, they often stay for considerable periods of time. Those who entered legally might overstay the limits set in their visa and thus slip into irregularity, some applying for asylum to regularize their status. It is increasingly observed that onward migration is prevented, but also that people realize that there are opportunities in Turkey and thus stay. Hence, transit migration, which is initially considered a migration flow can become part of the migrant stocks, this is another signal of a migration transition. Scope and statistics are considered below in the irregular migration section.

Migrant Stock

In 2000, there were 1,278,671 foreign-born persons in Turkey,16 most of these were assumed to be ethnic Turks; two-thirds were born in one of the top five countries of origin (Bulgaria, Germany, Greece, Macedonia and Romania). By 2010, the total stock of foreign-born persons was assumed to have risen to just over 1.4 million individuals.17 However, as many of these individuals would have acquired Turkish citizenship18 - from 1997 to 2009, 355,865 persons were naturalized19 - they would not be recorded as foreigners. Remarkably, the majority of these individuals are of non-Turkish and/or Muslim background.20

In addition, Turkey has received an increasing number of asylum seekers and displaced persons from many parts of the world

In contrast, in 2000, there were only 234,111 immigrants in Turkey according to TurkStat,21 while TurkStat recorded 776,000 foreign-born people in the 2011 Population and Household Survey.22 Between 2001 and 2004, around 160,000 residence permits were issued annually, which then increased to around 180,000 from 2006 to 2010. Of these, an average of 20,000 permits were issued for the purpose of employment and another 30,000 for studying.23 By 2013, the number of student permits had risen to 50,683.24 In addition, the number of work permits issued by the Ministry of Labor and Social Security increased from around 7,000 in 2004 to 14,200 in 2010 and 32,271 in 2013.25 According to the National Police Records, on 1st March 2007, there were 202,085 foreign holders of residence permits in Turkey.26 According to the 2013 OECD report, this increased to 220,000 in 2011.27 The OECD (2012)28 reports that in 2009, residence permit holders originated from 176 different countries. The greatest number of permit holders were from Bulgaria, Azerbaijan, Iran, Iraq, Russia, Germany, the United States, Former Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Kazakhstan and Greece.

In addition, Turkey has received an increasing number of asylum seekers and displaced persons from many parts of the world. Hence, we must add 66,574 international refugees (2014) from Iraq, Afghanistan, Iran, Somalia and elsewhere to the above figures. By the end of 2014, another 81,000 Iraqis had sought shelter in Turkey.29 From 1997 to 2011, 101,067 people applied for asylum.30 Some of these refugees were displaced a second time, as Iranians came from Iraq, Afghans from Iran and Pakistan or Iraqis from Syria. At the end of 2014, there were also 1.623 million registered displaced persons from Syria, who fall under temporary protection regulations.31 Refugees - because Turkey maintains a geographic limitation on the 1951 Geneva Refugee Convention – are expected to only reside in Turkey temporarily and are designated for resettlement or return if their asylum claim is rejected; thus, their numbers fluctuate. However, asylum procedures, resettlement and return can take a long time. Moreover, return of refused asylum seekers cannot always be enforced and not all refugees can be resettled or will be able to return home, as may be the case for many Syrians. For instance, from 1997 to 2011, 38,071 refugees were resettled, which accounted for only 38 percent of all persons who had applied for asylum in the same period;32 However, it should be noted that many asylum seekers move on to other countries, usually irregularly. In any case, many refugees will be staying in Turkey for longer periods of time and should be considered de facto immigrants.33

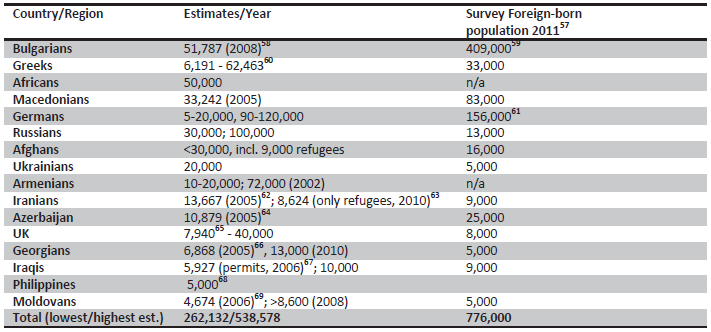

There are several immigrant nationalities that stand out. The estimates of the number of German migrants permanently living in Turkey ranges from 86,374 German nationals in 2000,34 5,000-20,000 in 2013 (according to the German embassy35) to 70,000 in 2010 (according to a German property broker36) or even 90-120,000 in 2012.37 There are assumed to be another 80,000-90,000 EU citizens in Turkey,38 although some sources claim there are up to 40,000 British nationals alone.39 Russian sources refer to 33,000 Russians in Turkey,40 but whether much higher newspaper estimates of 100,00041 are realistic cannot be verified. Moreover, Macedonians were assumed to represent a significant community of over 33,000 in 2005.42 Mat (2012)43 estimates that there are 10,000-20,000 Armenian migrant workers, an overwhelming portion of which are female migrants representing the proverbial “Armenian nanny.” In previous years, Hoffmann44 had estimated the total number of Armenians at 72,000, which probably included the 60,000 Armenian minorities in Turkey. There are also estimates of at least 50,000 Africans, one-third of which migrated from Sub-Saharan Africa, while the others are from northern Africa.45 Further publications suggest there are approximately 30,000 Afghans,46 20,000 Ukrainians47 and 13,000 Georgians48 as well as many smaller groups of migrants.

Immigrants are both dispersed and concentrated across various regions and specific urban districts. Police records imply that in 2008, there were 106,156 residence permit holders in Istanbul, 16,772 in Bursa, 13,832 in Antalya and 12,157 in Ankara.49 Currently, Syrians are mostly concentrated in southern Turkey, whereas 350,000 are estimated to live in Istanbul.50 Russian sources claim that Russian communities live in Istanbul (18,000), Antalya (around 10,000), and Ankara (5,000).51 Similar settlement patterns are reported for Ukrainians.52 Saul (2013)53 argues that there are between 5,000-7,000 migrants from West and Central African from French and English-speaking countries. He asserted that the greatest number of migrants are from Nigeria, Senegal and the DRC, with at least 1,000 migrants each. Salvir (2008)54 suggests that in Istanbul alone there were 8,597 Moldovan migrants in the mid 2000s; of these, 81.5 percent are supposedly women, mostly caretakers and domestic workers.55 Afghans are mostly concentrated in the Zeytinburnu district in Istanbul. Other districts in Istanbul such as Tarlabaşhı and Kumkapı are rather mixed.

Finally, there are also a significant numbers of irregular immigrants in Turkey. For the purpose of this article, they can be distinguished by three main types. First, there are transit migrants who enter Turkey legally but then overstay their visa or enter clandestinely with the intention of moving on to other countries, usually the EU; though they rather stay short periods of time and can often not be considered immigrants. Second, there are long-term, irregular immigrants such as individuals who overstay their visa, clandestine entries, unregistered refugees or rejected asylum seekers, and stranded transit migrants. Third, there are circular or transnational migrants who enter legally either visa-free or on a visa, some of whom may engage in irregular economic activities; these migrants may leave the country within the terms set by their visa but re-enter again or even frequently. Thus, whilst statistically these people are recorded as visitors, they are de facto temporary70 or transnational immigrants. This latter includes business people, (shuttle) traders and (circular) workers alike,71 as well as lifestyle and retirement migrants. Içduygu and Aksel (2012) suggest that due to changes in the migration characteristics of Turkey as well as visa politics and migration legislation, transit migration and the inflow of irregular immigrants have dropped significantly by four-fifths since the early 2000s;72 simultaneously, the “the use of illegal migrant labor is rapidly increasing,” notably in domestic work, construction and agriculture.73

Table 1: Estimates of international ammigrants in Turkey by countr or region

It is difficult to quantify the flow and stock of irregular immigrants. With respect to the numerical dimension, Içduygu and Aksel (2012) note that there were almost 797,000 apprehensions by the police, gendarme and coast guard between 1996 and 2009. Annual apprehensions dropped from 94,000 in 2000 to 34,345 in 2009, and then increased again to 94.045. By 2014, the total number rose to around 1 million. These numbers included the apprehension of inflowing and outflowing migrants at the border and in the country; two-thirds were reportedly transit migrants and one-third were labor migrants, with the largest groups coming from Moldova, Georgia, Romania, the Russian Federation and Ukraine. These were on average 47,000 transit migrants and 22,000 labor migrants per year between 1996 and 2014. However, Içduygu (2008) suggests that over time the balance of transit migration versus labor migrants and/or those who overstay their visa changed and that by the late 2000s, the proportion of immigrant workers and/or others who overstayed their visa had increased to 60 percent of all apprehensions.74 However, in a later report, he suggests the contrary.75 Nevertheless, these numbers only represent those who are apprehended, whilst the total number, including those who remain undetected, is higher. In 2003, Içduygu and Kirisci in separate publications estimated that the total number of irregular immigrants was between 500,000 and one million, but Içduygu has later suggested that the number has since decreased.76 Pusch (2012) suggests that the number of irregular immigrants is several times higher than the 180,000 permit holders.77 This discussion confirms that: (a) a migration transition is ongoing, in which more irregular immigrants chose Turkey as their destination or are compelled to stay as a result of enhanced controls on Western borders; and (b) it can be assumed that the level of irregular immigrants in Turkey is no less than 400,000 and well below the one million threshold.

Finally, the fact that Turkey’s permit holders are from 176 countries implies that Turkey has a hugely diverse immigrant population and is well integrated into the global migration order

According to the various figures discussed in this article, immigrants (1.4 million) constitute 1.93 percent of Turkey’s total population (75 million) using World Bank estimates,78 2.5 percent if taking UN figures,79 4.1 percent if refugees are included (3.2 million), or 4.8-5.3 percent (3.7 to 4 million) if irregular immigrants are added. However, according to the 2011 Population and Housing census, 100,000 of the 3.2 million households surveyed (3.15 percent) identified themselves as immigrants, meaning that they were residing abroad one year prior (which off course includes returning Turks).80 But the census was conducted before the influx of displaced people from Syria and thus seems to roughly coincide with the above calculations. In any case, the proportion of the foreign-born and immigrant population is low compared to countries such as Germany (11.9 percent) or Spain (13.8 percent); only the eastern EU member states have equally low or even lower proportions.81 Furthermore, the proportion of irregular immigrants is similar or even lower than several EU countries. While the irregular immigrant population is 0.53-1.06 percent in Turkey, it accounts for 0.7-1.37 percent in the UK (2009) and 1 percent in Italy (2008), whereas in Germany, it is around or less than 0.5 percent.82 However, the proportion of irregular immigrants to all immigrants (11-19 percent) is high compared to Germany’s 1.5-5.9 percent but similar to Italy’s 15 percent. These figures imply that Turkey does not have a numerically significant problem with irregular immigration, but rather a problem with properly regulating immigration.

Turkey displays a significant propensity to attract different kinds of immigration, as one category is more affluent, another is poorer, and a third consists of forced migrants who, due to their circumstances, may be destitute

Finally, the fact that Turkey’s permit holders are from 176 countries implies that Turkey has a hugely diverse immigrant population and is well integrated into the global migration order. Furthermore, the fact that the majority of naturalized citizens are of non-Turkish and partly non-Muslim background illustrates a certain diversification of Turkey’s population. While this diversity is lower in scale than in other immigration countries, its breadth is nevertheless similar to the diversity found in many other OECD countries such as Germany or the UK.

Determinants of Migration to Turkey

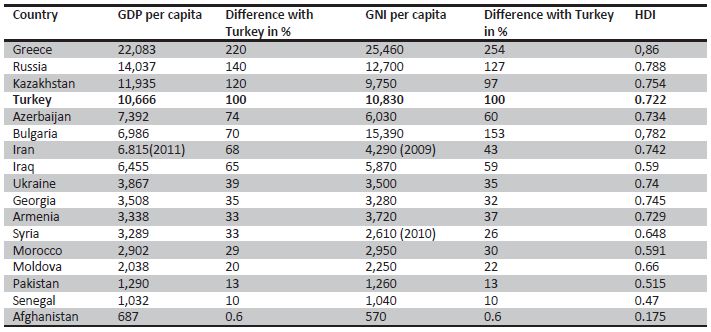

There are four main drivers of international migration: (1) political unrest; (2) economic disparities; (3) social forces such as chain migration and migration networks further fuelled by migration industries; and (4) individual ambitions, aspirations and perceptions. Related to this are macro-level structures, represented by migration systems and meso-level structures such as migration networks. Moreover, politico-legal opportunities and constraints shape migration flows.83 Of the 16 regional and sending countries, only three have higher GDPs and GNIs per capita than Turkey – Greece, Russia and Kazakhstan – whereas all others have significantly lower GDPs and GNIs per capita (see table 2).

Table 2: GDP and GNI per capita in $ and HDI, Turkey compared with its neighbors and some relevant sending countries (2012)84

A photograph from the meeting of International Migrants Day which is organized by the Directorate General for Migration Management in Ankara, 18 December 2014. | AA / Halil Sağırkaya

A photograph from the meeting of International Migrants Day which is organized by the Directorate General for Migration Management in Ankara, 18 December 2014. | AA / Halil Sağırkaya

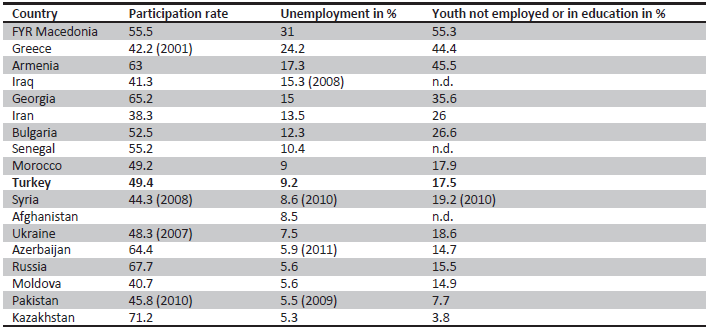

There are also significant discrepancies in the economic participation rate; it is lower than Turkey in eight countries in the region. Furthermore, total unemployment rates as well as youth unemployment rates between Turkey, its neighbors and other sending countries differ significantly; eight out of 17 countries have higher unemployment levels and nine have higher youth unemployment rates than Turkey.

Table 3: Unemployment and participation rate (figures for last available year)85

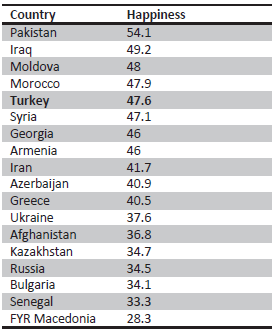

In addition, 13 of the countries in Turkey’s neighborhood display lower levels of happiness, while only four display a higher happiness index (see table 4). However, these figures are not entirely convincing, notably the high-level of happiness in Syria and Iraq, which contradicts intuitive assumptions and are now outdated anyway.

Table 4: Happiness Index86

Furthermore, Turkey has introduced a rather liberal, though complex, visa regime.87 So far, Turkey offers visa-free entry or issues a nearly condition-free e-visa to citizens from 55 countries. Citizens from other nations who already hold another OECD country visa are exempted from Turkish visa requirements or can obtain an e-visa. Thus, for many it is easier to enter Turkey than the EU, which further increases its attraction. This mobility is also facilitated by the rapid and continuous expansion of the Turkish Airline flight network; there are currently over 200 destinations in 105 countries. This expansion is driven by the idea “that we first have to connect Turkey to the rest of the world…a strategy that was initiated by top management and endorsed by the Turkish government… to improve our import/export economy and our relations with other countries.”88 Hence, it is a strategic decision to facilitate economic growth and improve Turkey’s international relations, which entails greater cross-border mobility. Finally, migrants already in the country generate what is called a migration network effect, meaning that they attract or facilitate further migration.89

If Turkey’s economy continues to grow while remaining politically stable, the country is likely to continue to attract immigration

In any case, macro-level factors, such as GDP, GNI, unemployment and the happiness index, suggest that Turkey offers better economic opportunities than most of the other countries in the region. However, it is meso- and micro-level factors, such as the social and human capital of potential migrants, the availability of legal migration channels and travel infrastructure that bring about actual migration.

Conclusion

Turkey is situated in or near regions of great economic and political disparity and volatility; it is in reach of the affluent but illiberal Gulf countries, poor republics in the Caucasus and Central Asia, troubled post-communist countries around the Black Sea, the war zones of the Middle East and unstable North African nations. On the macro-level, Turkey displays characteristics that are attractive to many citizens in these countries who see migration as an opportunity to improve their situation, as well as to citizens from more affluent nations for whom Turkey offers better living conditions and better value for their money. Thus, in structural terms, Turkey displays a significant propensity to attract different kinds of immigration, as one category is more affluent, another is poorer, and a third consists of forced migrants who, due to their circumstances, may be destitute. This is reflected by real but still comparably low levels of immigration from many countries in the region. If Turkey’s economy continues to grow while remaining politically stable, the country is likely to continue to attract immigration. Each different type of migrant – affluent or poor, high or low-skilled, European or non-European, Muslim or non-Muslim, permanent or temporary, regular, irregular or refugee, men or women, young or old – represents specific policy challenges. However, understanding of immigration in Turkey remains rather scarce and sketchy. Notably, we do not know the exact number or dispersal of immigrants across the country, migrants’ skills, education levels and economic performance, the economic, fiscal or social impact on Turkey or their (transnational) relations with their countries’ of origin. This calls for a comprehensive research program.

Endnotes

- Kemal Kirişçi and Ahmet Içduygu, both quoted in this article, highlight this shift for over a decade; for an overview see Juliette Tolay, “Discovering Immigration into Turkey: The Emergence of a Dynamic Field”, International Migration (2012, doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.2012.

00741.x). - As reflected in Directorate General of Migration Management, Migration (Ankara: DGMM, 2014).

- An excellent recent article by Basak Kale, “Transforming an Empire: The Ottoman Empire’s Immigration and Settlement Policies in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries”, Middle Eastern Studies vol 50, no 2 (2014) p. 252-271 reconstructs the immigration policy of the Ottoman Empire and thus the conditions under which immigration took place. Also see Kirişçi, Kemal, Turkey: a transformation from an emigration to an immigration country (Washington: Migration Policy Institute, 2003).

- Ahmet Içduygu, “A Panorama of the International Migration Regime in Turkey”, Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales, vol. 22, no. 3 (2006), p. 14.

- Ahmet Içduygu and Kristen Biehl, “Türkiye’ye Yönelik Göçün Değişen Yörüngesi”, Ahmet Içduygu (ed), Kentler ve Göç: Türkiye, İtalya, İspanya (Istanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları, 2012), p. 9-72.

- Kemal Kirişçi, Turkey: a transformation from an emigration to an immigration country (Washington: Migration Policy Institute, 2003).

- Barbara Pusch and Julia Splitt, “Binding the Almancı to the homeland – notes from Turkey”, Perceptions, vol. 18, no. 3 (2013), p. 129-166.

- Helen Baykara-Krumme and Bernhard Nauck, “Familienmigration und neue Migrationsformen. Die Mehrgenerationenstudie LineUp”, Aytac Eryılmaz and Cordula Lissner (eds.), Geteilte Heimat-50 Jahre Migration aus der Türkei (Essen: Klartext, 2011), pp. 136-146.

- Letter from TurkStat to the author, 21/1/2015; also see Ahmet İçduygu and Sule Toktaş, Yurtdışından Gelenlerin Nicelik Ve Niteliklerinin Tespitinde Sorunlar. Türkiye Bilimler Akademisi Raporları, 12 (Ankara: Türkiye bilimler akademisi, 2005).

- International Strategic Research Organization/ Uluslararası Stratejik Arastirmalar Kurumu (ISRO/USAK), Integration of settled foreigners in Turkey with the Turkish community: issues and opportunities (Ankara: ISRO, 2008), p. 6.

- Turkish Statistics Institute (TURKSTAT), Arrivals in Turkey by nationality, 2001-2011 (Ankara: Turkstat, 2011).

- World Bank, Net migration (Washington: World Bank, 2013), retrieved 13/7/2014 from http://data.worldbank.org/

indicator/SM.POP.NETM - OECD, Turkey, in International Migration Outlook 2012 (Paris: OECD, 2012), p. 278-279.

- Ahmet Içduygu, Zeynep G. Göker, Lami B.Tokuzlu and Seçil P. Elitok, Turkey, Migration Profile (Florence: Migration Policy Centre, 2013), retrieved 12/7/2014 from http://www.

migrationpolicycentre.eu/docs/ migration_profiles/Turkey.pdf - Ahmet Evin, Kemal Kirişçi, Ronald Linden, Thomas Straubhaar, Nathalie Tocci, Juliette Tolay and Joshua Walker, Getting to zero. Turkey, its neighbours and the West (Washington: Transatlantic Academy, 2010).

- State Institute of Statistics (SIS), 2000 Census of Population Social and Economic Characteristics of Population (Ankara: State Institute of Statistics (SIS), Printing Division, 2003).

- World Bank, Turkey, Migration and Remittances Factbook (Washington: World Bank, 2010),

retrieved 12/7/2014 from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTPROSPECTS/ Resources/334934-1199

807908806/Turkey.pdf - The ‘first citizenship law [or Nationality act] of Turkey was accepted in 1928. It was based on ius sanguinis but complemented by a territorial understanding. The second citizenship law from 1964 maintained the ius sanguinis principle [nationality by decent and thus ethnicity] and allowed for ius soli [nationality by residence] to prevent statelessness. …This law was amended many times [transforming] the law into an inconsistent patchwork. In 2009, a new citizenship law, Law No. 5901 – henceforth the Citizenship Law [Türk Vatandaşlığı Kanunu], was legislated in order to eliminate the inconsistencies’, see Zeynep Kadirbeyoğlu, Country report: Turkey, EUDO Citizenship Observatory (Fiesole: European University Institute, 2012), p. 1.

- See Ahmet Içduygu and Damla Aksel, Irregular Migration in Turkey (Ankara: IOM, 2012) , retrieved 14/7/2014 from http://www.turkey.iom.int/

documents/IrregularMigration/ IOM_Report_11022013.pdf - Ibid.

- Turkish Statistical Institute (TurkStat), Immigration 1995-2000 (Ankara: TurkStat, 2007), retrieved 15/7/2014 from http://www.turkstat.gov.tr/

PreIstatistikTablo.do?istab_ id=167 - TurkStat, Population and Housing Survey 2011 (Ankara: TurkStat, 2011), retrieved 20/9/2014 from http://www.turkstat.gov.tr/

PreIstatistikTablo.do?istab_ id=2050 - From Içduygu and Aksel, Irregular migration in Turkey”.

- OECD, [draft] Report on migration in Turkey (2014), given to author by the lead author Ahmet Içduygu.

- Ibid; Ministry of Labor and Social Security, Labour Statistics, Work Permits of Foreigners Statistics (2012) (Ankara: CSGB, 2012), p. 174-194, retrieved 10/102014, http://www.csgb.gov.tr/

csgbPortal/ShowProperty/WLP% 20Repository/csgb/dosyalar/ istatistikler/calisma_hayati_ 2012 - International Strategic Research Organization/ Uluslararası Stratejik Arastirmalar Kurumu (ISRO/USAK), Integration of settled foreigners in Turkey with the Turkish community: issues and opportunities (Ankara: ISRO 2008), p. 6.

- OECD, “Turkey”, OECD, International Migration Outlook (Paris: OECD, 2013), p. 3002-3.

- OECD, “Turkey”, OECD, International Migration Outlook (Paris: OECD, 2012), draft version, this figure was omitted from the print version.

- UNHCR, 2015 country operations profile – Turkey (Ankara: UNHCR 2014), retrieved 15/2/2015 from http://www.unhcr.org/pages/

49e48e0fa7f.html - Içduygu and Aksel, “Irregular migration in Turkey”.

- UNHCR, Syria regional refugee response (Ankara: UNHCR, 2014), retrieved 20/2/2015 from http://data.unhcr.org/

syrianrefugees/regional.php - See Refugee Council of Australia, 1993-213, rsmt, (2013), retrieved 11/7/2014 from http://www.refugeecouncil.org.

au/doc/1993-2012-Rsmt.xlsx - The UN definition of an immigrants is a person who resides in another country for 12 month or more.

- State Institute of Statistics (SIS), “2000 Census of Population Social and Economic Characteristics of Population”.

- German Embassy, Deutsche in der Türkei (Ankara: Deutsche Botschaft, 2013), retrieved 10/7/2014 from http://www.ankara.diplo.de/

Vertretung/ankara/de/04__ Aussen__und__EU__Politik/ Bilaterale__Beziehungen/ deutsche__in__der__tuerkei. html - Türkei-Objekte, Immobilienrecht (2010), retrieved 10/7/2014 from http://www.tuerkei-objekte.

com/ - Bianca Kaiser, “50 Years and Beyond: The ‘Mirror’ of Migration - German Citizens in Turkey”, Perceptions vol. 17, no. 2 (2012), p. 103-124, though her figure also includes ethnic Turks of German nationality.

- Kaiser, “50 years and beyond”.

- The Telegraph, “Britons with homes in Turkey could have residency cancelled” (The Telegraph, 2015), retrieved 17/2/2015 from http://www.telegraph.co.uk/

expat/expatnews/11383927/ Britons-with-homes-in-Turkey- could-have-residency- cancelled.html - Russia beyond the Headlines (RBTH), Amid Turkeys unrest Russians torn by conflicting emotions, (RBTH, 2013), retrieved 9/7/2014 from http://rbth.co.uk/

international/2013/06/17/amid_ turkeys_unrest_russians_torn_ by_conflicting_emotions_27141. html - See Hürriyet, “White Russians demand return of Turkish church” (Hürriyet Daily News, 21/5/2013), retrieved 10/7/2014 from http://www.bne.eu/system/

files/dispatch-pdf/2013-05-21/ 9c50-210513%20BNE%20TKY.pdf, p. 18 - IOM, Migration to Turkey, a country report (Geneva: IOM, 2008).

- Fazila Mat, Armenian migrants in Turkey: an all-female story (Rovereto: Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso, 2012).

- Tessa Hoffmann, Armenians in Turkey today (Brussels: Armenian Associations in Europe, undated, probably 2002), retrieved 9/2/2013 from http://www.armenian.ch/gsa/

Docs/faae02.pdf - Mahir Şaul quoted in International Business Times (IBT), “As Erdogan meets with Obama Africans in Turkey face racism, discrimination” (IBT, 2013), retrieved 9/7/2014 from http://www.ibtimes.com/

erdogan-meets-obama-africans- turkey-face-racism- discrimination-1265037 - Estimate by Esra Kaytaz, PhD researcher at Oxford University on Afghans in Turkey, this number includes around 9,000 refugees.

- Embassy of Ukraine in the Republic of Turkey, Ukrainians in Turkey, (Ankara: Embassy of Ukraine, 2012), retrieved 9/7/2014 from http://turkey.mfa.gov.ua/en/

ukraine-tr/ukrainians-in-tr - Tamar Shinjiashvili, Recent Migration Tendencies from Georgia (Princeton: Princeton University, 2010), retrieved on 20/2/2015, http://epc2010.princeton.edu/

papers/100642 - ISRO/USAK, “Integration of settled foreigners in Turkey with the Turkish community: issues and opportunities”.

- Interview with Istanbul municipality, 9/1/2015.

- RBTH, “Amid Turkeys unrest Russians torn by conflicting emotions”.

- Embassy of Ukraine, “Ukrainians in Turkey”.

- Mahir Şaul, African immigrants in Turkey, Istanbul (Illinois: Illinois University, 2013), retrieved 7/7/2014 from http://faculty.las.illinois.

edu/m-saul/projects.html - Mihail Salvir, Trends and Policies in the Black Sea Region: cases of Moldova, Romania and Ukraine (Chișinău: Institute for Development and Social Initiatives Viitorul, 2008).

- Oleg Galbur, Report referring to analyze the phenomenon of migration of Moldovan population, including health professionals (Chisinau: 2011), retrieved 10/7/2014 from http://old.ms.md/_files/11543-

Report%2520refering%2520to%2520the%2520migration.pdf - Compiled from the sources quoted in this article or given in the table; numbers are not comparable as they were collected or estimated in different years.

- TurkStat, ”Population and Housing Survey 2011”.

- See ISRO/USAK, “Integration of settled foreigners in Turkey with the Turkish community: issues and opportunities”.

- Most are ethnic Turks and have naturalized.

- Ahmet Içduygu and Deniz Sert, Country profile: Turkey (Bonn: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, 2009); IOM, Migration in Georgia, a country profile (Geneva: IOM, 2008).

- Figure includes Germany-born Turks.

- IOM, “Migration to Turkey, a country report”.

- Advocates for Human Rights (OMID), Report on the situation of Iranian refugees in Turkey (Berkeley, CA: OMID, 2010), retrieved 10/7/2014 from http://www.omidadvocates.org/

uploads/2/4/8/2/2482398/ report_on_the_situation_of_ iranian_refugees_post_june_ 12th_one_year_later.pdf - Içduygu and Sert, “Country profile: Turkey”.

- ISRO/USAK, “Integration of settled foreigners in Turkey with the Turkish community: issues and opportunities”.

- IOM, “Migration in Georgia”.

- Içduygu and Sert, “Country profile: Turkey”.

- Independent Balkan News Agency (IBNA), Turkey’s new minorities: 3.000 Russians and 5.000

Filipinos, (IBNA, 2013), retrieved 19/7/2014 from http://www.balkaneu.com/turkeys-minorities-3-000-

russians-5-000-filipinos/ - Içduygu and Sert, “Country profile: Turkey”.

- The UN recommends defining people staying three month or more but less than 12 month as temporary migrants.

- See Ahmet Içduygu, Rethinking irregular migration in Turkey (CARIM paper, Florence: RSCAS, 2008).

- Içduygu and Aksel, “Irregular Migration in Turkey”.

- Ahmet Içduygu, Zeynep Göker, Lami Tokuylu and Secil Elitok, “Turkey”, Phillip Fargue (ed), EU neighbourhood migration report 2013 (Florence: EUI, 2013), p. 246.

- Içduygu, “Rethinking irregular migration in Turkey”.

- Içduygu and Aksel, “Irregular Migration in Turkey”.

- Ahmet Içduygu, Irregular Migration in Turkey (Geneva: International Organization for Migration, 2003); Kirişci Kemal, “The Question of Asylum and Illegal Migration in European Union-Turkish Relations”, Turkish Studies, vol. 4 no. 1 (2003), o, 79-106 and Içduygu, “Rethinking irregular migration in Turkey”.

- Barbara Pusch, “Bordering the EU: Istanbul as a Hotspot for Transnational Migration”, Seçil Paçacı Elitok and Thomas Straubhaar (eds), Turkey, Migration and the EU: Potentials, Challenges and Opportunities (Hamburg: Hamburg University Press, 2012), p. 167–197.

- World Bank, “Net migration”.

- United Nations, Migrant stock (Washington: UN Population Division, 2013), retrieved 10/3/2013 from http://esa.un.org/unmigration/

TIMSA2013/Data/subsheets/UN_ MigrantStock_2013T3.xls, - TurkStat, Type of the Locality One Year Prior to the Reference Date and Type of the Locality of the Migrated Population at the Time of the Survey, 2010-2011 (Ankara: TurkStat, 2013), retrieved from 9/9/2014http://www.turkstat.

gov.tr/PreIstatistikTablo.do? istab_id=2057 - UN, “Migrant stock”.

- Data on irregular immigration in the EU was retrieved from the EU-funded project website Clandestino http://clandestino.eliamep.gr/

- So far see, for instance, Stephen Castles, Hein de Haas and Mark J. Miller, The Age of Migration (Houndsmill: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

- World Bank, GDP per capita (Washington: WB, 2012), http://data.worldbank.org/

indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD/ countries; World Bank, GNI per capita, Atlas method (current US$) (Washington: WB, 2012), http://data.worldbank.org/ indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD/ countries; UNDP, Human development index (Washington: UNDP, 2012), http://hdr.undp.org/en/data/ map/, all retrieved 10/3/2014. From New Economics Foundation, Happy planet index (NEF, 2013), http://www.happyplanetindex. org/data/, retrieved 10/3/2014. - Compiled from ILO, ILOSTAT (Geneva: ILO 2012), http://www.ilo.org/ilostat/

faces/home/statisticaldata?_ afrLoop=887184525929904&_adf. ctrl-state=1cior8u7oo_4; UN, Youth unemployment rate (Washington, UN, 2012), http://data.un.org/Data.aspx? d=MDG&f=seriesRowID%3A630, all retrieved 10/3/2014. - New Economics Foundation, “Happy planet index”.

- Cf Meral Acikgöz, this volume.

- Business Travel New, Interview: Turkish Airlines Director Of Corporate Agreements And Marketing Oğuz Karakaş (6/3/2014), retrieved 12/7/2014 from http://www.businesstravelnews.

com/Business-Travel/Interview- -Turkish-Airlines-Director-Of- Corporate-Agreements-And- Marketing-Oguz-Karakas/?ida= Airlines&a=trans - Douglas Massey, “Understanding Mexican migration to the United States”, American Journal of Sociology, vol. 92, (1987), p. 1372-403.