The Relationship between Nation Branding and Humanitarian Assistance

Nation branding is an important concept in today's world; it can be described as an increase in a country's positive recognizability in the world. As a consequence of globalization, all countries must compete with each other for attention, respect, and trust, investors, consumers, donors, immigrants, media, and advantage. It is essential for countries to understand how they are seen by the world.

Branding is not just a singular image or characteristic that helps distinguish one product from others. It is a process which creates a meaningful whole with physical, nonphysical, and psychological or sociological aspects. 1 In general, branding is essential across a large spectrum of economics, finance and marketing, and a key instrument of social science.

According to Anholt, the branding of the nation. 2 Szondi draws our attention to clear categories of national branding. 3 Nation branding supports countries in increasing their prestige; it provides a sense of pride and advantage to a country's citizens and canalizes them to withstand national and global competitiveness. 4 Aim The aim is to create a clear, simple, differentiating idea built around emotional qualities which can be symbolized in a variety of situations. To work effectively, the nation must be embracing political, cultural, business and sport activities. ” 5

Language, literature, sport activities, cultural events and political approaches

Nation branding has been classified into three categories: product-based, national-based and cultural-based. 6 In other words, the nation's branding reveals the national features which belong only to the nation. 7 Dinnie highlights that country branding does not merely promote a country's touristic opportunities, stimulate domestic and foreign trade and investments, and attract international students as part of its economic targets; it also tries to increase the value of a country's chief monetary unit and consolidate its political stability. Together, these efforts lead to an increase in nation building.8 Today, countries use to explain themselves to the world in many ways. Figure 1: They generally use simple and clear images, slogans and marketing techniques.

These images reveal the nation's branding strategies. While some states highlight their flag colors, in other words, their national or political identity, countries such as Maldives and Greece highlight their identity as tourism destinations. While countries are representing themselves, they tend to emphasize their famous features.

Turkey’s slogan, ‘Discover the Potential,’ has not become as famous as Holland’s tulip, or ‘I Love New York.’ Turkey’s prominence derives from such factors as its foreign policy and its leadership claim in the region, which are harder to crystallize into a single image or slogan. Yet, not all branding is about visual image. In his analysis of nation branding, Fan identifies four essential characteristics: public diplomacy, tourism, country of origin and national identity.10 Humanitarian assistance, one form of public diplomacy, matters a lot. In this paper, the main focus will be on the role of national identity in nation branding, and the function of humanitarian assistance in understanding nation branding.

In 2004, Georgescu et al.published a paper in which they describe national identity as multi-dimensional –in other words, a term that cannot be reduced to a simple definition. Moreover, they argue, the nature of national identity can change over time.11 “An ‘identity’ is not a thing, it is a description of ways of speaking about self and the community, yourself and your community and accordingly, it does not develop in a social void, but in relation to manifest forms of existence; ‘identity is a form of life.’”12 In a comprehensive study on this subject, Dinnie reports that national identity plays a pivotal role in nation branding. Strong national identity leads to strong nation branding campaigns because famous or high capacity companies or brands are not enough by themselves. Language, literature, sport activities, cultural events and political approaches contribute to the constitution of national identity, and create the nation brand value of the country.13

Unless there are strategic plans for the foreseeable future, Turkey’s brand value will not increase in the context of the Syrian refugee crisis. If there are to be any such plans, it is likely that TİKA will play a pivotal role

At first view, “brand’’ may be seen as a problematic concept in relation to humanitarian assistance, because the word evokes notions of marketing and trade. So, using the term ‘branding’ in relation to humanitarian assistance seems strange at first. Yet, it makes sense when we recognize that humanitarian assistance aims at moral duty, and at the same time, generates an image of a helpful and generous country in the mind of the public. When aid programs are managed logically, recipient countries develop positive dialogues and relations with the donor country, and the donor country’s image and reputation are affected positively in the eyes of the local, and sometimes global public, and gain the interest of foreign investors and corporations.

Brand Power at Work in Humanitarian Aid: Syrian Refugees in Turkey

The Syrian civil war began in 2011 and is still ongoing. It started with protests against Bashar al-Assad’s government in Deraa, and evolved into a widespread civil war in which more than 480,000 people have died.14 The Syrian refugee crisis has tested many countries, and the attitudes and behaviors of both hosting and transit countries have come under scrutiny, revealing a full spectrum of feelings from hatred to sympathy. For instance, in 2016 a Slovakian soldier shot a Syrian boy while he was trying to enter Slovakia from the Hungarian border. The Independentreported, “It is outrageous that Slovak authorities are shooting at innocent people fleeing war.”15 On the other hand, in 2015 a photographer captured a photo near the German-Danish border, which went viral with such responses as, ‘heartbreaking news’ or ‘touching;’ as a result, Denmark captured hearts with this spontaneous scene. In short, the sum of the images which are formed in people’s mind give us a sense of the relationship between ‘nation branding’ and humanitarian aid (or its opposite).

According to the December 2017 statistics of the UN Refugee Agency, 5,468,281 people have fled from Syria since the outbreak of civil war. 341,268 of them have been registered by the Turkish Government since 2011. 459,134 people are living in refugee camps in neighboring countries, and more than half of them are living in Turkish Refugee camps.16 At the end of the 7th year of the war, the Syrians have become the largest population of forced migration in the world and most of them are hosted in Turkey.17

The Syrian refugee crisis marks a turning point in Turkish foreign and domestic policies in the context of its humanitarian assistance policy and its effects on politics. Nonetheless, it is crucial to stress that in recent years there have been a tremendous number of critics of humanitarian assistance in the literature, who argue that this type of aid can be disastrous as it can create dependency for the receiving countries. However, these critiques and the debate surrounding the topic are for another study’s subject. In this paper, we attempt to clarify how Turkey has shaped its foreign policy in response to the Syrian refugee crisis and to examine what kind of nation brand value the country has created through the humanitarian assistance it has provided in response to this crisis.

Turkish Humanitarian Aid in Numbers

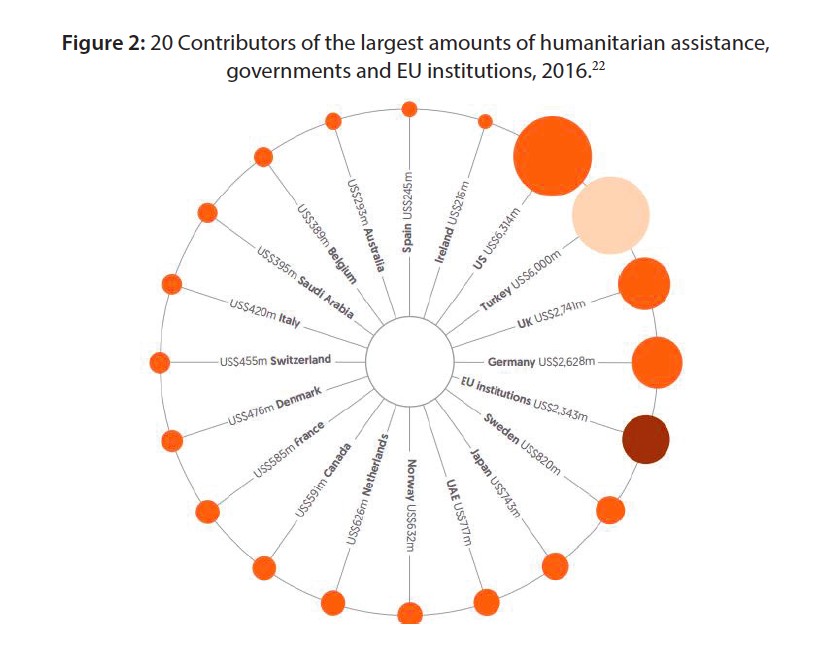

In 2016, more than 65.5 million people were displaced, both internally and internationally. Turkey hosted 4.2 million refugees, internationally displaced people, and asylum seekers in 2016, compared to 3.7 million people in 2015.18 According to the 2017 Global Humanitarian Assistance Report, Turkey has become the second largest donor country with $6 billion in donations around the world in 2016.19 Compared to the previous year’s report, the amount of donation increased 119 percent.20 In 2016, the proportion of humanitarian assistance going to the Syrian people was 99 percent in Turkish territory.

Looking at international humanitarian assistance as a percentage of gross national income (GNI) reveals the significance of humanitarian funding in relation to the size of a donor’s economy and its other spending priorities. Measured this way, when Turkey’s reported contributions are considered against its GNI, it spent 0.75 percent of its GNI in humanitarian assistance in 2016 (up from 0.35 percent in 2015); while the U.S., whose humanitarian assistance percentage of GNI was 0.03, ranked highest according to volume of funding.21

Data from the World Bank shows that Turkey hosts the highest proportion of Syria’s refugee population. The Turkish government is hosting them into two ways: First is the camp area, which houses Syrians under temporary protection (approximately 12 percent of them). The second is non-camp practice, i.e. the rest live in cities in rented or owned homes and most of them work in temporary jobs.23

Simon Anholt’s Good Country Index24 shows the summary of Turkey’s refugee crisis image. The categories of ‘health and wellbeing’ and ‘world order’ are the main indicators of Turkey’s image in the context of the refugee crisis. Turkey’s placement under the title of ‘world order’ is getting better year by year. The category looks at the rates of ‘refugees hosted’ and ‘refuges generated.’ Over time, Turkey’s ranking improved in two ways, dropping from 126th to 39th in the category of ‘world order,’ and raising its ‘health and wellbeing’ ranking from 20th to 22nd to 44th. The latter category includes measures of food aid and humanitarian aid donations.25 Anholt states that the Good Country Index does not merely measure what countries do at home, instead the Index aims to start a global discussion about how countries can balance their duty to their own citizens with their responsibility to the wider world because this is essential for the future of humanity and the welfare of the world.26 He underlines that today, humanity has to face challenges without borders, such as climate change, economic crisis, terrorism, drug trafficking, slavery, pandemics, poverty and inequality, population growth, food and water shortages, energy, species loss, human rights, migration; such global problems can only be addressed through international efforts.27 Therefore, the Good Country Index does not measure countries by ‘how’ they make their contribution, but ‘how much’ they contribute to these efforts.28

In the first years of TİKA’s establishment (1992-2002), the institution had the goal of extending technical support to the newly independent republics of the former Soviet Union in the Caucasus and Central Asia

From the beginning of the Syrian civil war in 2011, Turkey has come into prominence with three nation branding values: truthfulness, global power, and generosity.29 As may be seen in the latest reports,30 Turkey’s image as a generous country has a basis in fact. Turkey has supported the Syrian refugees with both public relief and financial aid. Turkey’s Disaster and Emergency Management Authority (AFAD) has provided biometric IDs for Syrian refugees to offer health and education services. Also, their fingerprints have been taken in case of security issues and other concerns such as access to health service. Yet, critiques have arisen toward Turkey in response to its global power claims. In particular, the visa liberation issue for Turkish nationals in European Union member states scored negative points for Turkey during the refugee crisis. Unfortunately, from the perspective of foreign audiences, visa-free travel for Turkish citizens was acknowledged as a matter of negotiation in discussions regarding the Syrian refugees at the Brussel Summit in 2016. “In exchange for refugees and visa-free travel alliance, EU member states will increase resettlement of Syrian refugees residing in Turkey, accelerate visa liberalization for Turkish nationals, and boost existing financial support for Turkey’s refugee population.”31 This bargain, leveraging the refugee crisis, makes foreign audiences think about Turkey’s truthful image and humanitarian claims.32

However, although Turkey has financially supported the refugees and increasingly shows a tendency to help them in other ways, there are a number of sociological, physiological, economic, and political challenges brewing. Unless there are strategic plans for the foreseeable future, Turkey’s brand value will not increase in the context of the Syrian refugee crisis. If there are to be any such plans, it is likely that the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TİKA) will play a pivotal role. The next section begins by examining TİKA’s structure and its process in general, with special attention to the Syrian refugee crisis period.

TİKA’s Role in Forming Turkey’s Nation Branding Value

Carrying out cooperation projects within the scope of development assistance in more than 140 countries on five continents, TİKA is one of Turkey’s brand engines at both the national and international level. Numerous projects and activities undertaken by TİKA significantly contribute to the positive recognition of Turkey around the world.

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Turkey began to take an active interest in the region, and initiated radical steps in different areas in order to strengthen its bilateral ties with the Turkic Republics of the former USSR.33The first and perhaps most important of these steps was the formation of TİKA, which was established according to the vision of Turgut Özalduring the presidency of Umut Arık in 1992. In January 1992, TİKA was established by means of Statutory Decree No. 480 as an international technical assistance agency under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and was later moved to the authority of the Prime Ministry in 1999.34Turkey thus began to take initiatives, with the help of TİKA, to seize opportunities emerging in the former Soviet basin, and to re-unify with Turkic peoples in the region. During this time, TİKA mainly served as an organization, which could enable activities and coordinate foreign policy priorities.35 Hence, the duties of regulating foreign aid granted by institutions or organizations in Turkey,36 and the establishment of coordination between institutions was given to TİKA by virtue of law No. 4668.37 In addition to these responsibilities, TİKA’s duties are defined in the first article of the law as follows:

Firstly those republics and related peoples who speak the Turkish language, and Turkey’s neighboring states, as well as developing states and peoples and other states are to be offered support by TİKA, and economic, trade, technical, social, cultural, and educational cooperation will be enhanced through projects and programs by TİKA, which operates under the Prime Ministry as its own legal entity.38

TİKA is one of the great powers in the sense of Turkish nation branding and helps uplift the prestige and reputation of Turkey all around the world

In recent years, thanks to its economic development track, Turkey has been taking significant steps with activities involving technical and foreign aid assistance in its region of operation.39 ‘Soft power,’ a concept coined and theorized by Joseph Nye and further developed by Geun Lee, is undoubtedly turned into practice via foreign aid; in this regard, studies have revealed that foreign aid is an important tool for foreign policy in the international system.40 One could argue, then, that TİKA plays an instrumental role in the increase of Turkey’s soft power.

Turkey: “The Most Generous Donor” Country in the World41

TİKA’s activities can be categorized into two different phases: 1992-2002 and 2002-2011. In the first years of TİKA’s establishment (1992-2002), the institution had the goal of extending technical support to the newly independent republics of the former Soviet Union in the Caucasus and Central Asia, and throughout the decade, undertook 2,241 projects. The number of projects undertaken by TİKA between the years 2003 and 2011 almost quadrupled. States for whom the most resources were directed in 2011 were (i) Afghanistan, 20.61 percent, (ii) Bosnia and Herzegovina, 6.76 percent, (iii) Palestine, 5.47 percent, and (iv) Lebanon, 3.89 percent.42 TİKA was renovated by Statutory Decree on October 24, 2011 by the Council of Ministers in order to increase its effectiveness in technical cooperation and coordination. The restructuring of TİKA was published in the Official Gazette dated November 2, 2011, No. 28103,43 and its name was changed from “Turkish Cooperation and Development Administration Directorate” to “Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency Directorate.”44 Baskın Oran notes that the Agency is particularly interested in the restoration of structures in the Ottoman basin that are inherited from the empire.45 This special interest is in line with the ‘historical depth’ understanding of Turkish foreign policy.

Turkey’s nation branding value, in the context of its national identity and its soft power, has been on the rise thanks to TİKA. In general, humanitarian aid may be evaluated in terms of soft power, but mostly has to do with the branding of the nation. While it is clear that the decision to provide foreign aid and forms of complementary cooperation should not be motivated by economic or commercial gains to the donor country, such aid and such cooperation does contribute to nation branding by yielding the country a special place in people’s hearts. As we will see below, TİKA is one of the great powers in the sense of Turkish nation branding and helps uplift the prestige and reputation of Turkey all around the world.

The Justice and Development Party (AK Party) leaders, who ascended to power in 2002, have been particularly interested in TİKA and its budget. The budget allocated to TİKA increased between the years 2003-2013 to almost five times that of the term between 1992-2002, and as of 2011, $1.2 billion in foreign aid was extended to over a hundred countries.46 In 2017, those numbers exceeded $6.4 billion to over 140 different countries.47 Today, those numbers have risen to $8.14 billion to 170 countries; of this amount, $7.2 billion is earmarked for humanitarian assistance.48

TİKA has exceeded its original areas of activity and carries its endeavors to a global level in keeping with the goals targeted by Turkish foreign policy

Kerem Öktem, who compared TİKA to its strongest counterparts in the world, notes that the German International Cooperation Community (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit-GIZ) has a $2.6 billion financial turnover, whereas TİKA tripled this number even in 2011.49 In addition to this, Öktem underlines that TİKA undertakes activities in South and Central Asia, the Middle East and the Balkans, including but not limited to health, education, and agriculture. Furthermore, Öktem emphasizes that in line with the proactive bent of Turkish foreign policy, TİKA’s activity areas extend from Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Kazakhstan, to Kosovo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Lebanon, Palestine, Iraq and Somalia.50 Put differently, Öktem notes that TİKA has exceeded its original areas of activity and carries its endeavors to a global level in keeping with the goals targeted by Turkish foreign policy.

In tandem with the new discourses in Turkish foreign policy, TİKA has undertaken projects in the reconstruction process of Afghanistan, and also plays a role in other areas, such as Africa, where it supplies clean water through drilling wells and constructing water pipes, and helps to remedy the consequences of natural disasters by supplying shelter and food. These activities and projects also help recipient countries in their processes of institutionalization. The technical assistance and foreign aid offered by Turkey to these countries guarantee the establishment of amicable bilateral relations; as the sole goal of an active and multi-dimensional foreign policy, the aim has been to reach the hearts of those countries, beginning with Turkish-speaking nations, and to revitalize relations based on a common historical background and cultural depth.51 TİKA’s activities also include education, trainings, and seminars so that qualified human resources and infrastructure can be further developed. Public officials from the Russian Federation’s autonomous Tatarstan Republic, personnel from the Albanian Export Promotion Agency, and the Uzbekistan Republic’s State Society and Institution Academy experts have all been trained in institutions in Turkey, and as a result of this, TİKA’s activities have also come to help the institutionalization processes in these states. With its projects and activities, TİKA enacts a foreign policy expansion from Central Asia to the Caucasus, to Eastern Europe and Africa, and in this regard may be called Turkey’s “vanguard.”52

As explained above, TİKA has been playing a stronger and more active role in the post-2002 period. Another instance of this is the increase in the number of its Program Coordination Offices, which TİKA increased from 12 in 2002 to 25 in 2011, and to 60 in 2018. As of 2018, TİKA operates in 58 different countries with 60 Program Coordination Offices.53 The President of Benin, Thomas Boni Yayi, visited Turkey on March 13, 2013. His speech during this visit is very meaningful in this regard:

Benin and Africa wish to juxtapose their power with the power of Turkey, and increase Turkey’s power. This I say with regard to petroleum and mine sources. En route to this richness, we also need to adopt the same vision, the same values in political views.54

Such penetration into even the smallest of the states on the African continent may be accurately interpreted as a relinquishment of the chronic patterns of Turkey’s Cold War era foreign policy and its transition from the issues of “high politics” and national interest-centered policies, as the realist theory would suggest, toward more value-centered policies, as the constructivist theory proposes. This is not to say that Turkey has foregone its national interests just because it follows policies in line with the constructivist approach; rather, with its foreign policy making in accordance with the constructivist theory’s understanding, Turkey is beginning to take steps from regional to global policies, and these policies constitute the bases of its African and Latin American openings.55 Hence, TİKA’s role in undertaking policies representative of this new understanding cannot be underestimated.

Ferhadija Mosque in Bosnia and Herzegovina, destroyed by the Serbian forces on May 7, 1993, and later reconstructed with the help of TİKA, was re-opened for worship on May 7, 2016. MIOMIR JAKOVLJEVIC / AA Photo

Put in more poetic terms, one might say that TİKA’s activities are resuscitating the heart that stopped with the fall of the Ottoman Empire. In line with Turkey’s mission to reinvigorate its connections of historical and cultural depth in Turkish speaking countries, TİKA has undertaken the restoration of the Orkhon Inscriptions in Mongolia, the Sultan Sancar Tomb in Turkmenistan, and the Sultan Murad Shrine in Kosovo. Thanks to these restorations, the sites have been re-opened to visitors, and they reflect the common culture, language, and history these countries share with Turkey.56 In a similar manner, TİKA’s activities and aids, such as its support in the reconstruction processes of Afghanistan57 and Iraq,58 serve as a guarantor for Turkey’s foreign policy understanding to the states in Turkey’s periphery. Consequently, TİKA has increased the number of activities and projects it undertakes in line with Turkish foreign policy and has become a significant actor supporting Turkey’s power both regionally and globally. It is by virtue of TİKA that Turkey aids those friendly and culturally related countries and creates a ‘peace belt’59 for Turkey.

With its humanitarian contributions to the world carried out by TİKA, Turkey stands as a beacon of hope for the region and the globe

Nonetheless, as a consequence of the Arab Spring, a civil unrest turned into a civil war in Syria. Therefore, when the first wave of Syrian refugees arrived in Spring 2011, Turkey admitted them. For doing so, since April 29, 2011, TİKA launched “Humanitarian Aid Operations for Syrian Crisis” with the coordination of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Turkey Prime Ministry Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency (AFAD) and the Turkish Red Crescent.60 Since then, Turkey has maintained an emergency response of a consistently high standard and declared a temporary protection regime, ensuring non-refoulement and assistance in 20 temporary protection centers, where an estimated 215,000 people are staying.61

Turkey’s Aid in Numbers

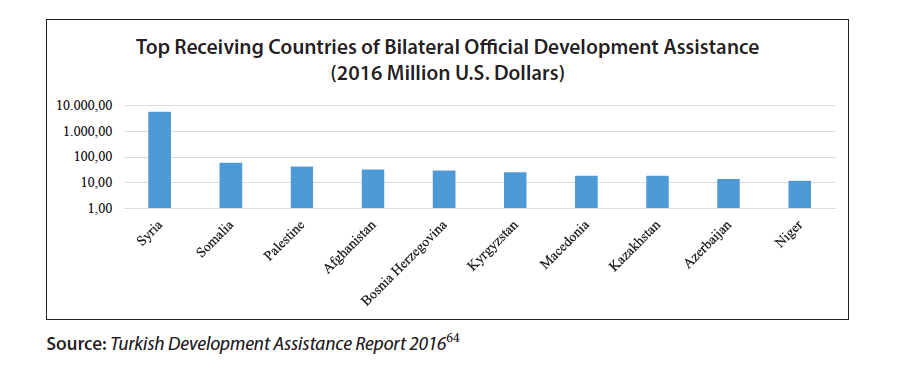

In 2016, Turkey provided $7,943.3 million in foreign aid.62 That figure consists of bilateral development aid, development assistance, and humanitarian assistances. The countries that received the highest amounts of bilateral official development aid from Turkey in 2016 are: Syria ($5,851.23 million), Somalia ($59.63 million), Palestine ($43.12 million), Afghanistan ($32.69 million), Bosnia-Herzegovina ($30.29 million), Kyrgyzstan ($25.39 million), Macedonia ($18.96 million), Kazakhstan ($18.96 million), Azerbaijan ($14.24 million) and Niger ($11.91 million).63

70 percent of Syria’s pre-war population is in need of humanitarian assistance. Through TİKA, Syrian refugees have become one of Turkey’s focus groups for humanitarian aid. Today, Turkey is a safe haven for almost 3.5 million Syrian refugees, who receive the largest share of Turkey’s assistance.

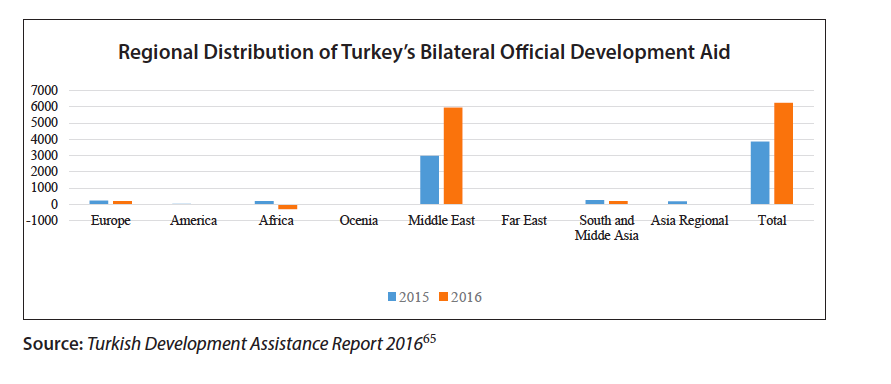

In addition to its support for the Syrian refugees, Turkey has provided foreign aid to many different regions. Between 2015-2016, Turkey nearly doubled the amount of foreign aid it offers. According to TİKA, the following regions receive bilateral official development assistance aid: Europe (2015: $222.9 million; 2016: $190.4 million), North and South America (2015: $19 million; 2016: $6.5 million), Africa (2015: $183.4 million; 2016: $306.2 million), Oceania (2015: $0.2 million; 2016: $0.5 million), the Middle East (2015: $2,988.4 million; 2016: $5,943.2 million), the Far East (2015: $6.1 million; 2016: $13.4 million), South and Middle Asia (2015: $256.6 million; 2016: $191.5 million), Asia Total (2015: $169.3 million; 2016: $0.1 million). In 2015, the total number of aid was $3,845.9 million; in 2016 this figure reached $6,237.5 million.

Conclusion

Since its foundation in 1992, TİKA has always been a major agent of Turkish foreign policy. Its founding purpose was to carry out joint projects and development assistance to the newly independent Turkic states in South Caucasus and Central Asia. Today TİKA operates as a global institution with 60 program offices in 170 different countries around the world. By carrying out its many operations, TİKA’s contribution to humanity amounts to $8.14 billion. In other words, thanks to TİKA, Turkey’s nation branding value and soft power have been on the rise. As one of the most generous countries in the world, Turkey has a special place in people’s minds and hearts as a consequence of its nation branding efforts. Furthermore, it can be seen from the Good Country Index (1.2), which places Turkey 38th in overall rankings, TİKA is one of the great powers in the sense of Turkish nation branding, and supports the prestige and reputation of Turkey all around the world. Despite the difficulties resulting from both external factors (the Syrian Civil War, instability in the Middle East, Balkans and South Caucasus, etc.) and internal factors (the coup attempt, terror attacks, etc.), in recent years, Turkey has not given up helping other countries via TİKA. Instead, as President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan stated in his speech at the TİKA Coordinators meeting: “[Turkey’s] humanitarian diplomacy crowned in the very heart of Turkish foreign policy.”66 In other words, with its humanitarian contributions to the world carried out by TİKA, Turkey stands as a beacon of hope for the region and the globe.

Endnotes

- Jean-Noel Kapferer, Strategic Brand Management: Creating and Sustaining Brand Equity Long Term, (London: Auflage, 1997), p. 2.

- Simon Anholt, Competitive Identity: The New Brand Management for Nations, Cities and Regions, (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007).

- György Szondi, “The Role and Challenges of Country Branding in Transition Countries: The Central and Eastern European Experience,”Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, Vol. 3, No. 1 (January 2007),

pp. 8-20. - Kyung Mi Lee, “Nation Branding and Sustainable Competitiveness of Nations,” Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Twente, 2009.

- Eugene D. Jaffe and Israel D. Nebenzahl, National Image and Competitive Advantage: The Theory and Practice of Place Branding, (Denmark: Copenhagen Business School Press, 2006).

- Ying Fan, “Branding the Nation: What Is Being Branded?” Journal of Vacation Marketing,Vol. 12, No. 1 (2006), pp. 5-14.

- Keith Dinnie, Nation Branding: Concepts, Issues, Practice,(Abingdon: Routledge, 2015), p. 15.

- Dinnie, Nation Branding, p. 17.

- Jasmine Montgomery, “Countries Need Better Logos and Branding than These Identikit Designs,” Digital Arts Online,(April 5, 2018), retrieved June 3, 2018, from https://www.digitalartsonline.co.uk/news/graphic-design/countries-need-better-logos-branding-than-these-identikit-designs/.

- Fan, “Branding the Nation,” p. 6.

- Anamaria Georgescu and Andrei Botescu, “Branding National Identity,” Master Thesis, Lund University, 2004, p. 6.

- Georgescu and Botescu, “Branding National Identity,” p. 6; Michael Billig, Banal Nationalism (Theory, Culture and Society),(California: Sage, 1995), p. 69.

- Dinnie, Nation Branding,pp. 111-112.

- “Death Tools in Syria,” I Am Syria, retrieved December 30, 2017, from http://www.iamsyria.org/death-tolls.html.

- Ashley Cowbun, “Syrian Refugee Shot by Border Guards Trying to Enter Slovakia from Hungary,” Independent, (May 9, 2016), retrived December 30, 2017, from http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/syrian-refugee-shot-by-border-guards-trying-to-enter-slovakia-a7020846.html.

- “Syria Regional Refugee Responses,” The United Nation Refugee Agency, (December 21, 2017), retrieved December 30, 2017, from http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/regional.php#_ga=2.20965769

1.85189626.1514645719-1672854974.1514645719; Monica Pinna, “Dünyaya Örnek Olarak Gösterilen Türkiye’deki Mülteci Kampları,” Euro News, (April 28, 2016), retrieved December 30, 2017, from http://tr.euronews.com/2016/04/28/dunyaya-ornek-olarak-gosterilen-turkiye-deki-multeci-kamplari. - “Syria Regional Refugee Responses.” According to the report, 55 percent of refugees come from Syria (nearly 6 million), Afghanistan (2.5 million), and South Sudan (1.4 million).

- “Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2017,” Development Initiatives, (June 21, 2017), retrieved December 25, 2017, from http://devinit.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/GHA-Report-2017-Full-report.pdf.

- “Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2017,” pp. 17-18.

- “Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2017,” p. 44.

- “Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2017,” p. 44.

- “Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2017,” p. 45. Development Initiatives based on Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC), UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Financial Tracking Service (FTS) and UN Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) data.

- “Turkey’s Response to the Syrian Refugee Crisis and the Road Ahead,” World Bank, (December 2015), retrieved December 5, 2017, from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/583841468185391586/pdf/102184-WP-P151079-Box394822B-PUBLIC-FINAL-TurkeysResponseToSyrianRefugees-eng-12-17-15.pdf.

- Simon Anholt, one of the pioneer academicians of Nation Branding literature, annually publishes an index called “The Good Country Index.” In measuring countries, Anholt takes into consideration their contribution to the common good of humanity. Anholt uses a wide range of data from the UN and other international organizations, giving each country a balance sheet to show at a glance whether it is a net creditor to humankind, a burden to the planet, or something in between. Anholt emphasizes that by doing so, he is not making any moral judgments about countries. Instead, by ‘Good Country’ he means something much simpler, namely “a country that contributes to the greater good of humanity,”

a country that serves the interests of its own people without harming –and preferably by advancing– the interests of people in other countries too. The index compiles data under the headings of Science and Technology, Culture, International Peace and Security, World Order, Planet and Climate, Prosperity and Equality, and Health and Wellbeing. For more information see, https://goodcountry.org/index/results. - This drastic decrease reflects the number of Syrian refugees who received citizenship status from Turkey. After their change in legal status, Turkey’s humanitarian assistance to them could not registered as foreign aid. The European Union and other affiliated international organizations also decreased their humanitarian aid to Syrian refugees living in Turkey.

- Simon Anholt, “The Good Country Index: A New Way of Looking at the World,” retrieved March 20, 2018, from https://goodcountry.org/index/about-the-index.

- Simon Anholt, “Why the Good Country Index?” retrieved March 20, 2018, from https://goodcountry.org/index/your-questions/background.

- Anholt, “Why the Good Country Index?”

- Senem Çevik and Efe Sevin, “A Quest for Soft Power: Turkey and the Syrian Refugee Crisis,” Journal of Communication Management, Vol. 21, No. 4 (April, 2017), pp. 399-410.

- For details see, “Turkish Development Assistance Report 2015,” TİKA,(2015), retrieved March

20, 2018, from http://www.tika.gov.tr/upload/2017/YAYINLAR/TKYR%202015%20ENG/KALKINMA%20.pdf. - Elizabeth Collet, “The Paradox of the EU-Turkey Refugee Deal,” Migration Policy, (March, 2016),

retrieved January 14, 2018, from https://www.migrationpolicy.org/news/paradox-eu-turkey-refugee-

deal. - “Turkey’s Refugee Crisis: The Politics of Permanence,” Crisis Group, (November 30, 2016), retrieved December 27, 2017, from https://www.crisisgroup.org/europe-central-asia/western-europemediterranean/turkey/turkey-s-refugee-crisis-politics-permanence.

- Güner Özkan and Mustafa Turgut Demirtepe, “Transformation of a Development Aid Agency: TİKA in a Changing Domestic and International Setting,” Turkish Studies,Vol. 13, No. 4 (2012), pp. 647-664.

- Law No. 4668, “Türk İşbirliği ve Kalkınma İdaresi Başkanlığının Teşkilât ve Görevleri Hakkında Kanun [The Law on the Organization and Duties of the Turkish Cooperation and Cooperation Agency],” was put into force on the date of its publication in the Official Gazette, Edition No. 24400, dated May 12,

2011, retrieved March 13, 2017, from http://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2001/05/20010512.htm#1. - “TİKA Hakkında,” TİKA, retrieved March 13, 2017, from http://www.tika.gov.tr/tika-hakkinda/1.

- Foreign aid: After World War II, the European countries were suffering from heavy wounds. During the Cold War, the U.S. supported these countries in dressing their wounds. Under the Truman Doctrine and Marshall Aid, the U.S. institutionalized its economic aid models. When TİKA’s structure and missions were organized, the U.S.’s foreign aid strategy and the Japan Official Development Assistance models were used as guidelines.

- Law No. 4668 “The Law on the Organization and Duties of the Turkish Cooperation and Cooperation Agency,” Resmi Gazete, retrieved March 13, 2017, from http://www.tbmm.gov.tr/kanunlar/k4668.html; for information about the duties of TİKA in the Prime Ministry Circular, see http://tika.gov.tr/depo/200511-sayili-basbakanlik-genelgesi.pdf.

- Law No. 4668, “The Law on the Organization and Duties of the Turkish Cooperation and Cooperation Agency.”

- Tuncay Kardaş and Ramazan Erdağ, “Bir Dış Politika Aracı Olarak TİKA,” Akademik İncelemeler Dergisi, Vol. 7, No. 1 (2012), p. 170.

- Hans J. Morgenthau, “A Political Theory of Foreign Aid,” The American Political Science Review, Vol. 56, No. 2 (1962), pp. 301-309.

- For details see, “Turkish Development Assistance Report 2015.”

- “TİKA’s 2011 Annual Report,” TİKA, (2011), retrieved March 13, 2017, from http://store.tika.gov.tr/yayinlar/faaliyet-raporlari/faaliyet-raporu-2011.pdf.

- Law No. 4668, “The Law on the Organization and Duties of the Turkish Cooperation and Cooperation Agency.”

- “TİKA’nın Adı Değişti!” Anadolu Ajansı, retrieved March 13, 2017, from http://www.aa.com.tr/tr/turkiye/16430--tika-nin-adi-degisti.

- Baskın Oran, Türk Dış Politikası Cilt 3, 2001-2012 (Kurtuluş Savaşından Bugüne Olgular, Belgeler, Yorumlar),(İstanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2012), p. 141.

- “TİKA Development Aid Report 2011,” TİKA, (2011), retrieved March 13, 2017, from http://store.TİKA.gov.tr/yayinlar/kalkinma-yardimi/KalkinmaYardimlariRaporu2011.pdf.

- “Türkiye’den 140 Ülkeye 6.4 Milyar Dolar Yardım,” Star, (May 24, 2016), retrieved March 15, 2017, from http://www.star.com.tr/ekonomi/turkiyeden-140-ulkeye-64-milyar-dolar-yardim-haber-1113237/.

- “Cumhurbaşkanı Erdoğan’dan Müslüman Ülkelere Zekât Çağrısı,” TRT Haber, (April 10, 2018), retrieved April 10, 2018, from http://www.trthaber.com/haber/gundem/cumhurbaskani-erdogandan-musluman-ulkelere-zekat-cagrisi-359928.html.

- Kerem Öktem, “Projecting Power: Non-Conventional Policy Actors in Turkey’s International Relations,” in Kerem Öktem, Ayşe Kadıoğlu and Mehmet Karlı (eds.), Another Empire? A Decade of Turkey’s Foreign Policy Under the Justice and Development Party, (İstanbul: Bilgi University Press, 2012), p. 86.

- Öktem, “Projecting Power,” pp. 86-87.

- Kardaş and Erdağ, “Bir Dış Politika Aracı Olarak TİKA,” p. 172.

- “TİKA Faaliyet Coğrafyasını Genişletiyor!”TİKA, (2015), retrieved March 13, 2017, from http://www.tika.gov.tr/tr/haber/tika_faaliyet_cografyasini_genisletiyor-15396.

- “TİKA Hakkında.”

- “Benin Cumhurbaşkanı Yayi, TBMM’de!” (March 13, 2016), Republic of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs, retrieved March 15, 2018, from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/benin-cumhurbaskani-yayi-turkiye_de.tr.mfa.

- For more details regarding that opening see, Erman Akıllı and Federico Donelli, “Reinvention of Turkish Foreign Policy in Latin America: The Cuba Case,” InsightTurkey, Vol. 18, No. 2 (2016), pp. 161-182.

- Öktem, “Projecting Power,” pp. 86-87.

- “TİKA’dan Afganistan’a Eğitim Desteği,” TİKA,(December 16, 2015), retrieved March 13, 2017, from http://www.tika.gov.tr/tr/haber/tika’dan_afganistan’da_egitim_destegi-22315.

- “Irak’ın Yeniden Yapılandırılması Çalışmaları,”Kerkük Vakfı, retrieved March 13, 2017, from http://www.kerkukvakfi.com/arastirmalar.asp?id=53.

- Since providing developmental aid to neighboring regions affects relations positively, it contributes to the ‘peace belt’ that surrounds Turkey, improving Turkey’s security and good relations with neighbors.

- “Turkish Development Assistance Report 2016,” TİKA, (2011), retrieved April 10, 2018, from http://www.tika.gov.tr/upload/2018/Turkish%20Development%20Assistance%20Report%202016/Turkish%20Development%20Assistance%20Report%202016.pdf, pp. 11, 94.

- “AFAD Geçici Barınma Merkezleri Raporu,” AFAD, (June 4, 2018), retrieved from https://www.afad.gov.tr/upload/Node/2374/files/04_06_2018_Suriye_GBM_Bilgi_Notu.pdf.; Erman Akıllı, “Turkey’s Arabian Middle East Policy and Syrian Civil War,” Hitit Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, Vol. 10, No. 2 (December 2017), p. 938.

- Development Turkish Development Assistance Report 2016, ” TİKA , retrieved April 10, 2018, from http://www.tika.gov.tr/upload/2018/Turkish%20Development%20Assistance%20Report%202016/Turkish%20Development%20Assistance%20Report 202016.pdf, p. 11th.

- “Turkish Development Assistance Report 2016,” p. 19.

- “Turkish Development Assistance Report 2016,” p. 17.

- “Turkish Development Assistance Report 2016,” pp. 26-27.

- “President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan spoke at the TİKA Coordinators Meeting,” Sabah , (April

10, 2018), retrieved from https://www.sabah.com.tr/gundem/2018/04/10/cumhurbaskani-erdogan-

.