The United States is in the process of recalibrating its foreign policy priorities and shifting its grand strategy. Since the Obama administration took power in 2008, observers of US foreign policy have expected major policy changes promised during the presidential campaign.1 Obama gave some signals of this change during the first two years of his administration by revitalizing relations with international institutions, and by appealing to the people of the Middle East in order to recover US standing in this part of the world. More importantly, the Obama administration attempted to build a new relationship with China, which has been considered by many the most important peer competitor of the US in the coming decades. In particular, the Strategic and Economic Dialogue meetings that were launched by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Secretary of the Treasury Timothy Geithner intended to establish an infrastructure for a stable relationship between these economic giants.

America’s Pacific Century

Although the Obama administration was in the process of shaping its strategy towards China during this time period, the 2010 midterm elections, in which economic relations with China constituted a major campaign issue for Republicans, accelerated this process. After some new key appointments in the White House and the State Department in early 2011, the administration signaled the preparation of a new US policy towards the Asia.2 With Hillary Clinton’s Foreign Policy article3 and later her policy speech at the APEC Summit meeting;4 this transformation in policy is now formalized and has a name—“America’s Pacific Century.” After focusing on Europe during the Cold War years and having spent the last 10 years in Iraq and Afghanistan, the United States has set up its new strategy with Asia at its center.

The new strategy in the region will be the first comprehensive strategy that the US has adopted towards the Asia-Pacific, specifically China, since the emergence of China as a major player at the global level

This new strategy in foreign policy, often dubbed the“Obama-Clinton doctrine” and considered by some analysts to be long overdue,5 took place as a result of rapid regional transformations in the Asia-Pacific region over the last decade.6 Since the end of the Cold War and the rise of China’s economy in the 1990s, there has been some debate among scholars, observers, and practitioners of US foreign policy regarding the best strategy to deal with a growing China. Those who perceive China’s growth as a threat to US security and economic interests have called for increasing assertiveness in US policy towards China and, in some extreme cases, suggested a form of “containment strategy” throughout the years.7 On the other hand, those who believed that what most now call G-2 can bring peace and prosperity to the region and stability to world politics and economy, defended engagement and partnership with China.8

For both parties, there are sufficiently strong and sophisticated arguments to support their cases.9 The alarmists have often cited China’s increasing military budget,10 (especially its attempt to build a massive navy), uncertainty of its military and strategic intentions,11 human rights violations, copyright infringements, and currency manipulation.Those who foresee an optimistic future have pointed out the co-dependent nature of economies in a globalized world and the possibility of cooperation in some key security issues, such as North Korea.12 Since the Southern tour of Deng Xiaoping and the opening of China to world markets in 1992, Washington has tried to keep a balance between alarmists and optimists. For more than 20 years, US policy makers pursued a complex engagement without abandoning the benefit of doubt. The new strategy in the region will be the first comprehensive strategy that the US has adopted towards the Asia-Pacific, specifically China, since the emergence of China as a major player at the global level.

In the article released during her Libya visit, Clinton reveals her administration’s strategy on Asia by stating that “the future of politics will be decided in Asia, not in Afghanistan or Iraq, and the United States will be right at the center of the action.”13 According to Clinton, the Pacific has become a key driver in global politics while the United States was busy struggling in Iraq and Afghanistan and allocating immense resources to those two wars. She states the necessity on the part of the US to focus on Asia in the next decade to sustain US leadership, secure US interests, and advance its values. For her, the first step of this strategy will be to devise some diplomatic, economic, and strategic means of assuring Asian nations on the US commitment to the region for the foreseeable future. President Obama underlined this message in every opportunity since the announcement of the new strategy and declared that America from now on will be in the Pacific and it will be there to stay.14

Clinton,in her article, also sends a message to the US domestic constituency and politicians who are increasingly raising their voices about the overextension of US forces and the need to focus more on the US economic meltdown and domestic issues, such as education instead of foreign policy. Against these isolationist voices, she responds, “those who say that we can no longer afford to engage with the world have it exactly backward, we cannot afford not to.”15 Clinton argues that this new strategy will be win-win for both the US and its allies. According to her, while the United States, as the only superpower with a network of alliances and no territorial ambitions, will play a key role in providing peace and prosperity in the region, the region will help the United States economically in terms of providing a vast and growing consumer base, and strategically by advancing US interests through countering the proliferation efforts of North Korea and ensuring both military transparency of regional countries and freedom of navigation in the South China Sea.16

In order to achieve these ambitious goals, Clinton put forward a strategy of “forward-deployed” diplomacy, which will include the dispatch of the full range of US diplomatic assets to every country and every corner of the Asia-Pacific region. This strategy will entail six different methods including the following: strengthening bilateral security alliances, deepening working relationships with emerging powers, engaging with regional multilateral institutions, expanding trade and investment, forging a broad-based military presence, and advancing democracy and human rights. Through these different policy initiatives, the United States aims to build a web of alliances and institutions just like the ones that it created across the Atlantic after World War II, including a partnership to promote free trade as well as a security cooperation framework in the region.17

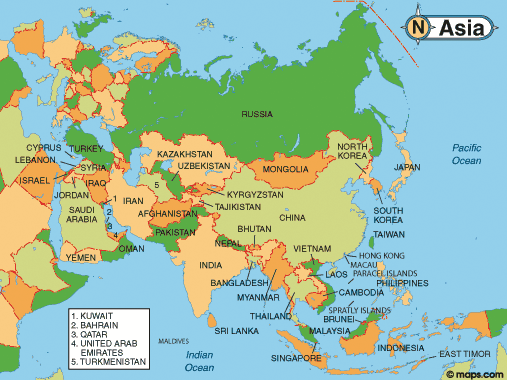

US foreign policy toward the region in the last three months following Clinton’s piece demonstrated that the Obama administration intends to follow through on its rhetoric. Immediately after this article, Clinton visited Central Asian countries, including Uzbekistan and Tajikistan,to discuss regional initiatives, such as the New Silk Road project, and broker a new deal between Uzbekistan and the US on the construction of a GM factory in Uzbekistan.18 In the same period, Secretary of Defense Panetta was touring the Asia-Pacific region and emphasizing the US commitment to maritime security in the Pacific and the freedom of navigation in the South China Sea.19 Following this, both President Obama and Secretary Clinton attended the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation(APEC) forum and gave speeches on the new Asia strategy. In the same week, Obama also attended the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) meeting where a deal worth 20 billion dollars between Boeing and Indonesia was also signed20 and travelled to Australia to officially announce that 2500 Marines will be sent to Australia and US ships will use the port in Darwin.21 President Obama became the first president to attend the East Asian Summit and a couple of weeks later Secretary Clinton paid a historic visit to Myanmar, the first in 50 years.

Transformation of US foreign policy strategy and priorities will also have important repercussions and implications for US policy and involvement in different parts of the world, including the Middle East

In addition to the White House and Obama administration, different branches and institutions of the US government also turned their focus on China and its relationship with the US. In recent weeks, some of these institutions announced new reports on China-US relations. Some of these reports emphasized possible threats to the US interests in the Asia-Pacific region and others focused on venues of cooperation for these two powers in different parts of the world. For example, the Senate Armed Services Committee last month declared that thousands ofUnited States’ warplanes, ships, and missiles contain fake electronic components from China, leaving them open to malfunction.22The US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, an advisory Congressional panel warned aboutChinese military firms and their practices and stated that Chinese cyber intrusions “came at a substantial volume in 2011 and that China has identified the US military’s reliance on information systems as a significant vulnerability.” The commission also warned the US administration about the economic problems between these two countries and more particularly with the unfair trading practices of the Chinese government.23The Office of the National Counter-Intelligence Executive declared that foreign industrial espionage against the US represents a significant and growing threat to the US and indicated China as the most aggressive country in terms of industrial and military espionage.24 A report by the RAND Corporation, which is known for being close to the Department of Defense, also stressed these concerns and underlined the possibility of conflict in the areas of cyberspace and economy between the US and China in the future.25 All of these reports demonstrate that in addition to the policy shift at the administration level, there is also increasing public discussion on the nature of the relationship between China and the US in American society.

This dramatic and historic transformation of US foreign policy strategy and priorities will also have important repercussions and implications for US policy and involvement in different parts of the world, including the Middle East, especially after the US announcement to pull out its troops from Iraq and Afghanistan. Of course, the pullout plan will not result in the total abandonment of the region by the US. Recently Secretary Panetta stressed that the US will continue to play an important role in the security of the Gulf region and the Middle East.26 The Obama administration plans to bolster American military presence in the Persian Gulf after the withdrawal from Iraq in order to respond to a possible security collapse in Iraq or a military confrontation with Iran. The repositioning of combat forces within the region may include new combat forces in Kuwait and a possible expansion of military ties with other members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC).27 Moreover, following the recent report by the UN nuclear watchdog organization, which revealed that Iran had carried out tests “relevant to the development of a nuclear device,”28 the US may devise some military contingency plans in the Persian Gulf. However, Washington’s new foreign and defense policy initiatives highlight a new framework for future US involvement in the region that necessitates further coordination with regional powers. The cuts in the defense budget and a decrease in the number of servicemen will require especially that the US look for possible venues of cooperation with other countries of the region.

Pacific Century and the Future of the US-Turkish Partnership

At this critical juncture of US foreign policy, US relations with Turkey also faces a major transformation. Analysts interpret the recent thaw in bilateral relations, especially in the increased cooperation between these two countries in the Arab Spring, after the crisis-driven year in 2010, as possible grounds for revitalizing the partnership.29 During significant periods of the Arab Spring, the two countries pursued parallel policies and coordinated their efforts to aid the democratization movements in the region.

The West can balance and counterweight China only with the inclusion of Turkey and Russia in the Western camp

In a recent piece, David Ignatius refers to this new working relationship that has been developed throughout 2011, as “one of the most important but least discussed developments shaping this year of change in the Arab world.” According to him, this partnership is actually one of the most important factors that can keep the Arab Awakening from turning into a nightmare. In particular, the rapport between President Obama and Prime Minister Erdogan, which started to develop last year, has played an increasingly important role in the formation of this new phase in bilateral relations and cooperation in the management of events in Egypt, Libya, and Syria.30

In addition to the Arab Spring, the parties also reached a common ground on some other critical foreign policy and security issues. For example, Turkey’s agreement to host the NATO radar system, the US vocal support for Turkey after the recent PKK attacks,31and the US decision to sell three Super Cobra attack helicopters and four Predator UAVs,32 mostly to be used against the PKK, provided significant opportunities to build mutual trust. At this moment, a critical question arises on the possible impact of the American Pacific strategy on the future of this revival of Turkish-American relationship and cooperation. Prominent strategists, such as Zbigniew Brzezinski have been recommending strengthening of this partnership in order to deal with global problems and challenges. They argue that the West can balance and counterweight China only with the inclusion of Turkey and Russia in the Western camp.33 But it will be vital to figure out the nature of this partnership and deepen existing bonds.

An important part of this new period is that the transformation of US foreign policy is coinciding with a period of change in Turkish foreign policy. Turkey is currently attempting to follow a more multilayered and multidimensional foreign policy and trying to connect to the different parts of the world. On one hand, Turkey is playing a more assertive role in the Middle East and abandoning its practice of non-involvement and non-interference in regional politics. On the other hand, it is exploring different opportunities for cooperation in other regions, such as Asia and Africa. Turkish foreign policy makers’ efforts to establish relationships in the Asia-Pacific overlap with US attempts to rejuvenate its relationship with this region.

In recent years, Turkey increased its trade volume with certain Asian economic powerhouses, such as China and Japan,34 and signed numerous bilateral economic relations agreements with these countries. Especially Turkish-Chinese economic relations have strengthened in recent years and trade volume between the two has increased, although this has resulted in a trade deficit on the part of Turkey. Political exchanges have also become more frequent over the last ten years. However, this relationship faced an important challenge during the Chinese crackdown of Uyghur demonstrators, as happened in Urumchi in 2010 when Prime Minister Erdogan blamed the Chinese government for committing genocide in the region.

The overlapping Turkish and American interests in the Asia-Pacific region may serve to consolidate an emerging new partnership by increasing the sensitivity of both of these countries to the economic and political developments in the region

Turkey has increased high level diplomatic exchanges and started to improve its diplomatic relations with other regional powers, including India and Indonesia, which together with Turkey are considered rising powers (as part of TIMBI).35 Bilateral trade witnessed a significant increase in recent years and Turkey is currently negotiating free trade agreements with both of these countries.36 Furthermore, social relations with Indonesia, which have expanded after the earthquake and tsunami in the region in 2004, reached a new high with the annulment of reciprocal visa requirements.37 Turkey also launched initiatives to improve its relations with other countries of the region, including Malaysia, with whom Turkey is negotiating a free trade agreement,38 and with South Korea, which is another state that is expected to challenge the great powers in coming decades.39 Turkey and South Korea signed a joined action plan that covers political, economic, cultural, and security issues of concrete cooperation between 2012 and 2016 and built the infrastructure for a free trade area agreement.40 Although Turkey’s economic and trade initiatives are quite recent and are not comparable with US economic relations with the region, Turkey’s establishment of these ties over a relatively short amount of time shows promise.

The overlapping Turkish and American interests in the Asia-Pacific region may serve to consolidate an emerging new partnership by increasing the sensitivity of both of these countries to the economic and political developments in the region. Turkey and the United States both have strong economic relations with China and both can adopt a posture critical of human rights violations in this country. The use of force by Chinese security forces on demonstrators and its suppression of dissenting groups may not eradicate economic ties, but in every instance, it strains bilateral relations and creates social outrage toward China in Turkey and harsh reaction by rights groups in the US. The US strategy in the Asia-Pacific and Turkey’s coinciding regional foreign policy opening may pave the way for new areas of cooperation and coordination for these countries, especially in terms of economic relations which are considered the weakest link in Turkish-American relations. Thus, the free trade areas that both countries are negotiating in the region can play an indirect role in improving economic ties. In addition, the US, Turkey, and the countries of the region can transform their economic cooperation into political coordination and form partnerships within international organizations.

While the US is rearranging its priorities and relocating its resources towards the Asia-Pacific region, the partnership between Turkey and the US will be vital for promoting shared interests in other parts of the world, such as stability in the Middle East, security of energy pipelines in Central Asia, and improving economic relations with Africa. Particularly, cooperation between the two countries will play a key role in providing support for the countries in the midst of political upheavals and in the post-US withdrawal from Afghanistan and Iraq. In the meantime, the shift in US strategy towards Asia may also open a new window of opportunity for cooperation between the US and Turkey, especially in Africa and Central Asia, by balancing the power of third countries and outweighing them in terms of economic relations with these countries. This partnership, however, will be different than the alliance against the Soviet Union during the Cold War. In its new independent foreign policy and new position as one of the few emerging regional powers in the international system, Turkey aims to follow a more balanced approach with other regional powers and a more multilayered strategy in its relations with individual countries. This will mean a more equal relationship with the US and more willingness on the part of Turkey to become a geostrategic player, game maker, and norm giver in its region, instead of being a geopolitical pivot and a norm and policy taker.41Thus, the new partnership needs to be less hierarchical, more horizontal, and considerate of mutual goals, interests and concerns. If these conditions can be met, the Asia-Pacific opening may help the US and Turkey develop a “special partnership” just as the Arab Spring brought them closer than ever.

Partnership in the Middle East

The doctrinal shift in US foreign policy is taking place in a period when the Arab Spring is shaking the foundations of Middle Eastern politics. The turmoil and uncertainty in the region and the possibility of state failures and civil wars, which can be unfortunate symptoms of some democratic transitions in countries with weak institutions and sectarian cleavages, necessitate closer cooperation between the US and Turkey. These two countries can cooperate in preventing and containing domestic conflicts in multiethnic countries of the region during their transition to democracies and form multinational initiatives to prevent bloodshed. The recent collaboration on Libya and Syria between the US and Turkish governments may create a pattern of cooperation. The reactions of third countries to the economic, political or humanitarian interventions inregional conflicts, such as the Russian and Chinese opposition to sanctions against the Assad regime in Syria, may necessitate a better coordination between the US and Turkey in international forums. Especially, in operationalization of the norm of “Responsibility to Protect,” these two countries need to create a common understanding on the conditions, timing, and strategy of possible diplomatic, economic or military interventions.

The most significant issue area for the partnership in the coming years will continue to be the Arab Spring and its consequences.In recent years, Turkey has gained influence and popularity among the people in the Arab world and is increasingly becoming a source of inspiration for many since the start of demonstrations in the Middle East. Economically, 7.5 percent expected growth in the economy in a period when the global financial meltdown has paralyzed some of the neighboring European countries leaves Turkey as one of the few countries in the world that still can grow and expand its economy.42 Political reforms in Turkey in recent years make Turkey an important source of motivation and inspiration for the democratizing forces in the Middle East.

The assertive foreign policy Turkey pursued before the Second Iraq War and its stance against the Israeli operations in Gaza added to Turkey’s prestige in the region and increased its impact on Arab public opinion. A recent survey compiled by Shibley Telhami of the University of Maryland demonstrated that Turkish Prime Minister Tayyip Erdogan continues to be the most popular leader in the Arab World and Turkey is perceived more favorably than any other country in terms of playing a constructive role in the Arab Spring.43 Moreover, although the Turkish side always cautiously approached the “Turkish model” argument, in terms of political transformation of the Arab world, the concept is becoming increasingly popular among intellectual circles as a viable option for the future of transition.44 In fact, as recently stated by Elias Harfoush:

This is the powerful Turkey on the political, military, and economic levels. It is the Turkey that can stand up to Israel, impose its terms on NATO and represent a successful commercial partner for the European Union. It is also ruled by an Islamic party that deals with the Western parties and Christian blocs from the position of an equal.

This is the model that is being followed by the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and Syria, the supporters of the Nahda in Tunisia, and the Islamists of Morocco and Libya. This is a model that is making Turkey turn “Arab” as never before, even under its Ottoman sultans.45

The US has a considerable amount of clout in Middle East politics, due to its immense economic and military resourcesand it retains a substantial number of troops as well as civilian officials in the region as part of its “civilian surge” strategy in Iraq. However, the US has been suffering fromchronic low standing and public approval in the Arab world. The new Asia-Pacific strategy, which entails the relocation of some resources in the region may stretch US influence further in the Middle East. To cooperate with Turkey, whose soft power is becoming one of its most important assets, may become essential to provide security and stability in the region.

In addition to the Arab Spring, the partnership between Turkey and the US is also going to be vital in Iraq and Afghanistan, particularly after the pull out of a significant portion of US troops from these countries. Turkey and the United States share similar concerns about the future of Afghanistan and many of Turkey’s diplomatic initiatives in the region have goals similar to US objectives, which include protecting territorial integrity of these countries, improving relations between Afghanistan and Pakistan, and increasing its economic integration. Turkey has shown its willingness and commitment to be part of the peaceful resolution of conflicts and fostering cooperation among the nations in the region by hosting a recent meeting of Afghanistan’s neighbors and Central Asian countries in Istanbul and bringing together the leaders of Afghanistan and Pakistan multiple times in Turkey to broker an agreement between the parties.46

Iraq constitutes an important area where the US and Turkey can cooperate in the post-withdrawal period. After Obama’s announcement that the US will pull its troops out of Iraq, Turkey and the United States started to discuss possible security complications and implications of the withdrawal from the region. Turkey is particularly concerned about the security of Northern Iraq, cross-border infiltration of the PKK militants into Turkey in the absence of US forces, and the surveillance of the border region.47 After the October 19th PKK attack, which left 24 Turkish soldiers dead, the administration in Washington as well as senior members of Congress also made statements acknowledging Turkey’s concerns and the possible destabilizing role that the PKK can play in the region.48 At this point, to establish a better coordination and cooperation between the parties in countering terrorism becomes imperative to prevent possible crises in relations due to misperceptions and mistrust. Furthermore, both countries acknowledged the threat that a sectarian conflict in Iraq may pose to the security and stability in the region as well as economic and financial relations of Turkey and the US with the region.

In spite of these areas of cooperation, Turkey and the US still face important challenges in this new partnership on issues such as Iran.49 When combined with the US apprehension over the Iranian nuclear dilemma and the rift between the two countries over the Tehran Declaration of May 2010, the issue becomes more sensitive on both sides. Although parties partially resolved this impasse when Turkey allowed NATO radar systems to be hosted on Turkish territory, and despite a considerable amount of uproar on the Iranian side,50 the issue is still “too nuclear to underestimate.” Increasing concerns about a unilateral Israeli strike to Iranian nuclear facilities, if realized, may especially strain US and Turkey relations. In a period when the US is trying to focus on the issues in the Asia–Pacific, a possible dispute in this issue may result in unintended consequences and spread to other areas of cooperation. As a result, in his last visit to Turkey, Vice President Biden was cautious in describing the situation to journalists. While asking for the implementation of tougher sanctions against Iran, considering the energy dependence of Turkey, Biden said that “the United States and Turkey might disagree ‘tactically’ about sanctions on Iran, but shared the same strategic goal.”51 It is also significant to remember at this point that the US also had disagreements with China and Russia on the issue of Iran and, although Turkey’s policy priorities and concerns do not exactly match the Chinese and Russian positions, there is again a multidimensional relation that both sides will need to balance.

Partnership in Central Asia and Africa

The shift in US foreign policy towards the Asia-Pacific may also pave the way for new venues of cooperation between Turkey and the United States, particularly in Africa and Central Asia. Part of the new Asia-Pacific strategy is to pay more attention to other regions left “unattended”over the last decade and where China has become an important player. Since the late 1990s, China has become increasingly pro-active in Africa and developed very close relations with the leadership of many African nations, including Zambia, Congo and Kenya, mostly because of dire need for natural resources and minerals to provide energy and infrastructure to its booming industry.52 However, aside from intervening in the economies of these African countries by purchasing the mines and signing multibillion dollar infrastructure deals, China has also become a political actor in these countries’ domestic and foreign policies.53In consideration of the increasing assertiveness of Chinese foreign policy in Africa, the US also took some steps to gain a foothold in the region as early as 1998, when Clinton paid a historic visit to Africa. This policy also continued during the Bush administration, which launched ambitious social and economic initiatives in the region, including a multilateral debt relief initiative, which aimed to reduce the burden of highly indebted poor countries, and the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief.54 It has accelerated during the with Obama administration, which launched initiatives such as Feed the Future Program the Global Climate Initiative.55 Recently the Obama administration started to be overtly critical of the Chinese influence in Africa. Secretary Clinton in her last visit to Zambia stated that the Chinese model of economic development and governance should not be a model for Africa and the African renaissance should be more open and depend on good governance.56 Moreover, in addition, to providing security for the ungoverned spaces in Africa and combatting terrorism, the formation of AFRICOM in 2007 was also partly a response to the increasing Chinese engagement in Africa.

During the same time period that the Bush administration launched its major foreign policy programs in Africa, Turkey also started to explore the region and tried to form economic and social relations with African countries.57 The major initiatives on the part of Turkey started only after 2005, which was declared as the “year of Africa” in Turkish foreign policy.58 After this period Turkish foreign policy makers worked actively in the region to increase its diplomatic and economic presence in different African capitals. Since then, Turkish officials have paid high level visits to African countries, brought together their counterparts in summits, and launched important education initiatives, such as exchange programs for African students and development projects through the Turkish Agency for Cooperation and Development (TIKA). Turkish civil society organizations and business associations also initiated different programs to foster economic cooperation between Africa and Turkey. Turkish companies have built a presence on the continent, such as Arcelik, which agreed to buy the South African company Defy Appliances for 327 million dollars. In a recent report by the Financial Times, Turkey was listed together with Thailand, Indonesia, and Saudi Arabia as rapidly rising countries in terms of economic relations with Africa.59

The power vacuum which may arise as a result of the US commitment to the Asia-Pacific region will provide new opportunities for Turkey but may also result in new security threats

Although both Turkey and the US are still far behind Chinese commitment to and influence in the long run they can jointly form projects and initiatives that can complement each other.These programs may entail development and humanitarian assistance programs in African countries, initiatives which would be vital to prevent humanitarian crises as a result of drought and famine, and forming trilateral economic relations with individual African countries, which would allow African countries to diversify their resources and market their natural resources. Moreover, both countries have important interests in providing security, especially in the Gulf of Aden and the Horn of Africa for shipping and preventing maritime piracy. These forms of cooperation would be beneficial to mutual economic interests and, in some circumstances, even serve to balance Chinese dominance in some parts of the continent.

Another region of concern for the US-Turkish partnership in this new era will be Central Asia. Since the establishment of independent states in Central Asia, both Turkey and the US have tried to cultivate close cooperation with this region, but have failed to devise a long term working strategy, leaving the region mostly in the Chinese and Russian spheres of influence. In the 1990s, Turkey failed to reach its ambitious goals in the region and to create a ‘Turkish century’ due to its negligence of regional realities, such as other regional powers including China and Russia, and as a result of Turkey’s limited economic and political resources.60 Although strong economic relations were formed with Central Asian countries and important projects were initiated, especially in the realm of energy cooperation this did not lead to economic integration. Moreover, the existence of historic, religious and ethnic ties with the people of this area did not bring political cooperation. In recent years, Turkey has recalibrated its foreign policy towards the region and initiated a new set of policies, which mainly focus on balancing its relations with other regional powers, including Russia, Iran, China, India and Pakistan, promoting stability and prosperity in the region, and facilitating energy transfer through its own territory, whose outcomes are still to be determined.61

The US also did not have a solid policy regarding the future of the region following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Throughout the 1990s, Washington was particularly concerned about China’s policies in the region. In thepost-September 11th period,the Afghanistan operation was the first eye opener for Washington to move Central Asia higher on the foreign and security policy agenda and a reminder that the region may mean more than energy security. Since then the US engaged with Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan to acquire permission for military bases to provide support lines in its operations in Afghanistan and continued to involve in energy pipeline negotiations. However, although the Tulip Revolution in Kyrgyzstan and the meetings of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization created short term Central Asian fevers in Washington, the US administrations has still not able to devise effective strategies in relation to countries of this region and its policies are mostly energy-focused. As a result, many regional initiatives, such as the SCO and a possible Eurasia Union, which was recently suggested by Putin,62 were put forward by either China or Russia.

In the new Asia-Pacific strategy, the US presence in the region will become increasingly critical due to its proximity to Afghanistan and due to its energy resources. The US administration has put forward initiatives such as the “New Silk Road” to boost north-south trade linking India and Pakistan via Afghanistan to the former Soviet republics of Central Asia.63 In her first trip after the publication of her article in Foreign Policy, Secretary Clinton paid a visit to Uzbekistan and Tajikistan to push forward this initiative.64 Turkey’s recent efforts to be involved in the reconstruction process in Afghanistan and the Istanbul forum that was convened in October 2011 were attempts to be among the game makers in the politics of the region.65

The US and Turkey can also play an active role in political and economic reforms of the countries in this region. The recent democratization movements in Kyrgyzstan and ethnic clashes in the Osh region demonstrated that the transition to a democratic government can be challenging and may need the attention of international actors. Moreover, possible leadership changes in more authoritarian countries, such as Uzbekistan, can also destablize not only that country but also its neighbors due to the intricate demographic structure in the region, which do not always correspond with territorial boundaries. For analysts like Richard Weitz, Turkey’s pro-activism in the region can play a constructive role in the region, especially in regards to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization’s increasing anti-Western stance. According to Weitz, a possible role for Turkey in the SCO may make Turkey a “dialogue partner” and may have a direct impact on the future of the organization. According to him “Washington might see Turkey’s entry as a means to help keep the SCO from moving in an anti-Western direction by diluting Moscow’s and Beijing’s domination of the organization.” This speculation becomes more meaningful in a period when SCO members were planning to expand their influence in the Afghan conflict and started to take steps toward a regional economic cooperation conference on Afghanistan for next year.66 However, it is important to realize that the current pragmatic foreign policy in Turkey does not necessitate the improvement of relations with the US at the expense of relations with SCO members or a Cold War-type alliance or a commitment to protect and promote Western interests and agenda in the region. It will require a careful evaluation and a fine balancing act on the part of Turkey to prevent possible misperceptions of its foreign and security policies.

Conclusion

The new era in US foreign policy, which will bring increasing concentration on the Asia-Pacific region, and particularly on China, will lead to the initiation of new instruments and strategies in US foreign and security policies. This will not only shape bilateral relations between China and the US but also have global implications. These transformations also necessitate revision of the Turkish-US partnership to meet the demands of this new era. Especially at the critical juncture of Middle Eastern politics, the still under-diagnosed US-Turkey “model partnership” needs to be properly defined to include methods for strengthening cooperation in existing and emerging areas.

The power vacuum which may arise as a result of the US commitment to the Asia-Pacific region will provide new opportunities for Turkey but may also result in new security threats. Although Turkey and the US have shared concerns regarding Iraq and Afghanistan, Iran may still be a possible seismic zone in bilateral relations. In case of possible disputes between China and the United States in these areas, Turkey may be obliged to follow a trilateral diplomacy in order to keep its relations workable with both countries. This trilateral diplomacy will be particularly significant in other regions, such as Africa and Central Asia. To promote cooperation in these areas, Turkey and the US need to strengthen their economic interaction and financial and trade volumes, which is miniscule compared to their political and strategic relations.

Although in recent years both countries pursued parallel strategies of using economic statecraft and trade and financial interactions in their foreign policies,67 until today the economic cooperation between Turkey and the United States has remained one of the weakest links in their bilateral relations. Both administrations have taken important steps to improve economic cooperation and to increase the volume of trade, such as the establishment of the US-Turkey Framework for Strategic Economic and Commercial Cooperation, and regular meetings of the Turkey and United States Economic Partnership Commission.68 These ties still, however, need to be strengthened in order to have a full-fledged, stable, and comprehensive partnership in the Middle East and in the Asia-Pacific. The economic relations will need to be fully integrated into the model partnership framework. Finally, since the nature of this partnership will have to be significantly different than the Cold War alliance in many ways, Turkey will continue to take an independent stand and pursue more multi-dimensional and multi-layered relations with different countries. This multidimensional foreign policy, whose misperception was the source of some important crises between the United States and Turkey in the last ten years, will have to be acknowledged in the new era.

The revival of the Turkish-American partnership last year has been a result of mutual respect and understanding on both sides and if both actors want to pursue the relationship in the coming Asia-Pacific decade of the US, these delicate principles need to be observed by both parties. To reinforce binary dialogue and a horizontal relationship while precluding the possible clash of ideas from transforming into crisis and expanding over into realms is a key requirement.Ultimately, Turkey and the US should now prepare for the possible opportunities and problems in this new international system and take strategic revisions into consideration.

Endnotes

- Barack Obama, “Renewing American Leadership,” Foreign Affairs, July/August 2007. http://www.foreignaffairs.com/

articles/62636/barack-obama/ renewing-american-leadership - In the last six months, the most senior official in the White House and member of the National Security Council on Asian affairs, Jeffrey Bader, was replaced by Dan Russel, who is an expert on Japan, and the Undersecretary of State James Steinberg, who was the top name in the State Department on Asian affairs, was replaced by Nicholas Burns, leaving Kurt Campbell, Assistant Secretary of State on East Asian affairs, another expert on Japan, as the most significant person in the State Department. Both Steinberg and Bader were criticized for being ‘soft’ towards China. New York Times. April 2, 2011. “Shake-Up Could Affect Tone of U.S. Policy on China” http://www.nytimes.com/2011/

04/09/world/asia/09diplomacy. html - Clinton, Hillary. 2011. “America’s Pacific Century,” Foreign Policy. Also available at http://www.foreignpolicy.com/

articles/2011/10/11/americas_ pacific_century - Remarks by Hillary Rodham Clinton. “America’s Pacific Century” Available at http://www.state.gov/

secretary/rm/2011/11/176999. htm - See the debate on Clinton’s article. “Debating the Pacific Century,” Foreign Policy http://www.foreignpolicy.com/

articles/2011/10/14/debating_ the_pacific_century?page=full - It should be stated that although the changes in US foreign policy towards Asia also have a domestic dimension. Domestically, the sharp economic downturn in the US since the mortgage crisis and the resulting high unemployment rate made US public opinion extremely sensitive to issues concerning China. The tension between China and the US in the economic realm, especially on US complaints about constant currency manipulation on the part of China, which resulted in a trade advantage for China and off-shoring of a lot of industrial plants to China had been on the agenda in the last congressional elections in 2010 and is currently grabbing the attention of Republican candidates in primaries. Ahead of the 2012 presidential election, the Obama administration is also pre-empting possible criticisms about US non-involvement in the region and being soft on China with a possible diplomatic and economic surge in the region.

- Mearsheimer, John. 2001. Tragedy of Great Power Politics. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

- Brzezinski, Zbigniew. Jan 5, 2005. “Make Money, not War,” Foreign Policy. Also available at http://www.foreignpolicy.com/

articles/2005/01/05/clash_of_ the_titans - For an exchange between Brzezinski and Mearsheimer on China, see the Foreign Policy debate: “Clash of the Titans,” Available at: http://www.foreignpolicy.com/

articles/2005/01/05/clash_of_ the_titans - Jane Perlez, “Continuing Buildup, China Boosts Military Spending More Than 11 Percent,” New York Times, March 4, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/

03/05/world/asia/china-boosts- military-spending-more-than- 11-percent.html - Abraham M. Denmark, “The Uncertain Rise of China’s Military,” Congressional testimony delivered before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, March 10, 2011 http://www.cnas.org/node/5959

- For an overview of the arguments of these two schools, see Xia, Ming. ““China Threat” or a “Peaceful Rise of China”? in New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/ref/

college/coll-china-politics- 007.html - Clinton, Hillary. 2011. “America’s Pacific Century,” Foreign Policy

- Reuters. Nov 17, 2011 “Obama tells Asia, US here to stay,” http://www.reuters.com/

article/2011/11/17/us-obama- asia-idUSTRE7AF32X20111117 - Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Eurasianet.org. Oct 24, 2011. “Uzbekistan: Clinton Visits GM Plant; Activists Say Workers Forced to Pick Cotton” Available at: http://www.eurasianet.org/

node/64362 - New York Times, Oct 24, 2011. “U.S. Pivots Eastward to Address Uneasy Allies,” Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/

10/25/world/asia/united- states-pivots-eastward-to- reassure-allies-on-china.html - Reuters, Nov 18, 2011. “Obama hopes for boost from Boeing-Indonesia jet deal,” Available at http://www.reuters.com/

article/2011/11/18/us-boeing- indonesia- idUSTRE7AH0FL20111118 - BBC News. Nov, 16, 2011. “Obama Visit: Australia agrees to US marine deployment plan,” Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/

world-asia-15739995 - Bloomberg News. Nov 8, 2011. “China Counterfeit Parts in U.S. Military Aircraft,” Available at: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/

2011-11-07/counterfeit-parts- from-china-found-on-raytheon- boeing-systems.html - US-China Economic and Security Review Commission. Nov 2011. Report to the Congress. Available at: http://www.uscc.gov/annual_

report/2011/annual_report_ full_11.pdf - ICIS News “US names China as top industrial espionage agent,” http://www.icis.com/Articles/

2011/11/03/9505317/us-names- china-as-top-industrial- espionage-agent.html - Dobbins, James, David Gompert, David Shlapak, and Andrew Scobell. 2011. Conflict with China: Prospects, Consequences and Strategies for Deterrence. Rand Corporation: Washington, DC.

- Jim Garamone, “Panetta Discusses U.S. Focus on Pacific, Middle East,” Department of Defense News, March 9, 2012, http://www.defense.gov/news/

newsarticle.aspx?id=67481 - New York Times. Oct 29, 2011. “US Plans post-Iraq troop increase in Persian Gulf,” http://www.nytimes.com/2011/

10/30/world/middleeast/united- states-plans-post-iraq-troop- increase-in-persian-gulf.html? pagewanted=all - BBC World News. Nov 18, 2011. “Iran Nuclear: UN voices deep concern over plans,” http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/

world-middle-east-15797177 - Zogby, James. December 4, 2011. “Turkey’s Changing Regional Role,” in Huffington Post.

- Ignatius, David. 7 Dec, 2011. “U.S. and Turkey find a relationship that works,” http://www.washingtonpost.com/

opinions/us-and-turkey-find-a- relationship-that-works/2011/ 12/06/gIQAh5UcdO_story.html? - Bloomberg Businessweek. Dec 2, 2011. “Turkish-U.S. Fight Against PKK to Be Widened, President Gul Says,” http://www.businessweek.com/

news/2011-12-02/turkish-u-s- fight-against-pkk-to-be- widened-president-gul-says. html - Today’s Zaman. 29 Nov, 2011. “US vice president to visit Turkey amid turmoil in region,” http://www.todayszaman.com/

news-264266-us-vice-president- to-visit-turkey-amid-turmoil- in-region.html - Zbigniew Brzezinski, Strategic Vision: America and the Crisis of Global Power (New York: Brass Books, 2012).

- Sabah. Feb. 22, 2012. “Chinese and Turkish relations to further strengthen.” http://english.sabah.com.tr/

National/2012/02/22/chinese- and-turkish-relations-to- further-strengthen - Gladstone, Jack. Dec. 2, 2011. “Rise of the TIMBIs.” http://www.foreignpolicy.com/

articles/2011/12/02/rise_of_ the_timbis? - Economic Times, Jul. 28, 2010. “India, Turkey studying FTA possibilities.” http://articles.economictimes.

indiatimes.com/2010-07-28/ news/27592483_1_trade-pacts- bilateral-trade-turkey - Simandjuntak, Djisman. Apr. 5, 2011. “Giving a tailwind to Turkey-Indonesia relations,” Jakarta Post. http://www.thejakartapost.com/

news/2011/04/05/giving-a- tailwind-turkey-indonesia- relations.html - Borneo Post. March 2, 2012. “Malaysia-Turkey trade may hit US$5 billion after FTA — Mustapa.” http://www.theborneopost.com/

2012/03/02/malaysia-turkey- trade-may-hit-us5-billion- after-fta-mustapa/ - Council on Foreign Relations, March 14, 2012, “Beyond the BRICS.” http://www.cfr.org/global-

governance/beyond-brics/p27648 - NewEurope. Jan. 29, 2012. “Turkey, South Korea to finalise trade deal.” http://www.neurope.eu/article/

turkey-south-korea-finalise- trade-deal - The terms of geostrategic player and geopolitical pivot belong to Zbigniew Brzezinski. The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives. (New York: Basic Books, 1997)

- New York Times, Dec 4, 2011, “For Turkey, Lure of Tie to Europe Is Fading,” http://www.nytimes.com/2011/

12/05/world/europe/for-turkey- lure-of-european-union-is- fast-fading.html?pagewanted=1& _r=1 - Telhami, Shibley. Nov 21, 2011. The 2011 Arab Public Opinion Poll. Presentation at Brookings Institution. Available at: http://www.brookings.edu/

reports/2011/1121_arab_public_ opinion_telhami.aspx - Bloomberg News. Nov 28, 2011. “Syria’s Muslim Brotherhood Favors Turkey Model Over Iran in Plan for Power.” Available at: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/

2011-11-28/syria-s-muslim- brotherhood-favors-turkish- model-over-iran-s-leader-says. html - Harfoush, Elias. November 30, 2011. The Arab Turkey. AlArabiya.Net. http://english.alarabiya.net/

views/2011/11/30/180017.html - Voice of America News, Nov 2, 2011, “Istanbul Meeting on Afghanistan Stresses Cooperation,” http://www.voanews.com/

english/news/asia/Istanbul- Meeting-on-Afghanistan- Stresses-Cooperation- 133104658.html - Hurriyet Daily News, Oct 26, 2011, “US and Turkey mull post-pullout for Iraq,” http://archive.

hurriyetdailynews.com/n.php?n= us-and-turkey-mull-post- pullout-for-iraq-2011-10-26 - Hurriyet Daily News, Nov 7, 2011. “US Senator: Iraq pullout risks Turkey,” http://archive.

hurriyetdailynews.com/n.php?n= 8216iraqi-withdrawal- threatens-turkey8217-2011-11- 07 - Bloomberg BusinessWeek, Dec 5, 2011, “Biden Seeks Turkey’s Help to Keep Up Pressure on Syria, Iran” http://www.businessweek.com/

news/2011-12-05/biden-seeks- turkey-s-help-to-keep-up- pressure-on-syria-iran.html - Washington Post, Nov 26, 2011, “Iran threatens to target NATO missile shield in Turkey if attacked by US or Israel,” h ttp://www.washingtonpost.com/

world/middle-east/iran- threatens-to-target-nato- missile-shield-in-turkey-if- attacked-by-us-or-israel/2011/ 11/26/gIQA1R7jyN_story.html - Al Arabiya News. Dec 5, 2011. “US, Turkey ready to help Syria after Assad; Hamas scales back presence in Damascus,” http://www.alarabiya.net/

articles/2011/12/05/180868. html - The Telegraph, Nov 25, 2011 “China builds its African empire while the ‘anti-colonialist’ Left looks the other way,” http://blogs.telegraph.co.uk/

news/damianthompson/100119769/ china-builds-its-african- empire-while-the-anti- colonialist-left-looks-the- other-way/ - The Economist, Apr 20, 2011. “The Chinese in Africa: Trying to Pull Together” http://www.economist.com/node/

18586448 - Brookings.edu, Dec 2, 2011. “President George W. Bush’s Trip to Africa: Reflections on Foreign Policies toward Africa,” http://www.brookings.edu/

opinions/2011/1202_bush_ africa_kimenyi.aspx - James Butty, “Assessing Obama’s Africa Policy, Looking at 2012 and Beyond,” Voice of America News, January 11, 2012, http://www.voanews.com/

english/news/africa/Butty- Africa-Obama-Second-Term- Kimenyi-11january12-137073473. html - Clinton: China not model for Africa,” Politico44 Blog, June 11, 2011 http://www.politico.com/

politico44/perm/0611/dont_ look_east_34fe2d77-7e7b-4a93- a87e-a34d13cbb87a.html - Davis, Carmel. 2009. “AFRICOM’s Relationship to Oil, Terrorism, and China,” Orbis

- Disisleri Bakanligi. Turkiye Afrika Iliskileri. http://africa.mfa.gov.tr/

turkiye-afrika.tr.mfa - Keyur Patel. “Thailand, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia and Turkey make their mark in Africa,” Financial Times beyondbrics Blog. March 16, 2012. http://blogs.ft.com/beyond-

brics/2012/03/16/thailand- saudi-arabia-indonesia-and- turkey-make-their-mark-in- africa/#axzz1pR3axbcl - Devlet, Nadir. Nov 10, 2011. “Taking Stock: Turkey and the Turkic World 20 Years Later.” GMF On Turkey Series.

- Aras, Bulent. May 18, 2008. “Turkish Policy Towards Central Asia,” The Journal of Turkish Weekly. http://www.turkishweekly.net/

news/55400/turkish-policy- toward-central-asia.html - Reuters, Oct 3, 2011. “Russia’s Putin says wants to build “Eurasian Union,” http://www.reuters.com/

article/2011/10/03/us-russia- putin-eurasian- idUSTRE7926ZD20111003 - Kucera, Joshua, Nov, 25, 2011. “U.S. Plan for a ‘New Silk Road’ Faces a Big Speed Bump: Iran,” http://www.theatlantic.com/

international/archive/2011/11/ us-plan-for-a-new-silk-road- faces-a-big-speed-bump-iran/ 249048/ - Eurasianet.org, Oct 24, 2011. “Uzbekistan & Tajikistan: Visiting Clinton Offers NDN Appreciation, Cautions on Religious Rights,” http://www.eurasianet.org/

node/64366 - Reuters, Oct 30, 2011. “Aiming low at Istanbul meeting on Afghanistan,” http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/

45093867/ns/world_news-south_ and_central_asia/t/aiming-low- istanbul-meeting-afghanistan/# .TuN2tGNFu7s - Weitz, Richard. Nov 11, 2011. “Can Turkey Save Afghanistan?” The Diplomat http://the-diplomat.com/2011/

11/11/can-turkey-save- afghanistan/ - Shortly after publishing her piece in Foreign Policy, Secretary Clinton put forward a new term for the future of US diplomatic endeavors—“economic statecraft.” She asserted that the US would give more weight to economic tools for diplomatic strategies in the coming decades and pursue political goals together with economic ones. Clinton mentioned the Strategic and Economic Dialogue rounds with China and aforementioned “New Silk Road Project” as examples of the use of economic instruments in foreign relations. Turkey has also been utilizing a similar strategy, especially in the Middle East, and pursuing the goal of economic integration in its near abroad for some time. Trade agreements with Middle Eastern countries which were intended to pave the way for the free flow of goods and services and promote peace and stability in the region have been pointed to as some of the most important pillars of Turkey’s new foreign policy strategy.

- VOA News. Oct 2, 2011. “Improving U.S.-Turkish Economic Partnership,” Available at: http://www.voanews.com/policy/

editorials/middle-east/ Improving-Turkish-Economic-- 131385958.html