Distance Matters

One way to examine Turkey’s quest for multi-dimensional and effective foreign policy is to focus on the development assistance and responses to humanitarian crisis. As poverty, inequality, human resource weakness, economic vulnerability and humanitarian crisis continue to haunt global politics, Turkey, in search of being a global actor, has become involved deeply with such a policy and given a political priority to development cooperation activities and humanitarian assistance. The political will of active engagement with such issues, found positive responses, in less than a decade, and Turkey’s efforts has become subject of numerous praises, particularly in terms of its pace and effectiveness.1

“If I request computers from the UN, they will take months and require a number of assessments. They will spend $50,000 to give me $7,000 of equipment. If I request computers from Turkey, they will show up next week” says Mohamed Nour, the Mayor of Mogadishu, Somalia, in September 2013 when he was asked about Turkish aid to Somalia.2

In January 2013, the President of Somalia, Hassan Sheik Mahmoud, elaborated on what he defined as the features of the Turkish model in Somalia.

“The Turkish model in Somalia is very, very clear… They said we want to do this thing in Somalia, and they do it. They are there. They come there, starting from their top leadership, the prime minister of the country with his family, the rest, deputy prime minister, ministries. There is a deputy prime minister who comes to Somalia every other month just to monitor and see how the projects are going on. They are building or implementing projects that are really tangible ones… They are doing the work there. They are driving their own cars. They are moving the city. They are building. They are teaching. They are – and there are a number of clinics that provide a free service to the people in Mogadishu alone. They are doing the same thing – they started doing the same thing in Puntland and Somaliland… Today Mogadishu is cleaner because of the support of the Turkish. They provided the garbage collection trucks and everything and the city is cleaner today.”3

Neither the President nor the Mayor is alone in praising Turkish aid. Since 2011, virtually all political actors, refugees, representatives of UN, and NGOs from and outside of Turkey have made similar comments. Two years later today, Turkey’s humanitarian aid to Somalia has become one of the most well-known acts that has gained the hearts and minds of people in Africa and elsewhere.4

There are reasons for Somalians to focus on the “being there” aspect of international-humanitarian aid, as almost all urgent humanitarian aid to Somalia for the last 20 years has been coordinated at a physical distance because of “security concerns.” While there is no doubt that security matters, Turkey is not immune from such a concern as, in addition to several other attacks and threats, its embassy was recently subject to a deadly assault.5 Despite the security situation, Turkey has been active in the re-building of Somalia, particularly since August 2011 with the historic visit of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.6Urgent humanitarian aid has developed into a comprehensive program for rebuilding Somalia and Turkey has been defined as the only country “investing in the stability of Somalia unlike other countries waiting for stability to invest.”7 Further, Turkey has also been active to a varying degree in several countries with similar security problems, such as Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, etc.8

While there is no doubt that the effectiveness of international aid suffers from insecure political conditions, such a context is not unfamiliar to aid activities and it cannot be the sole factor to explain the difficulties of international aid. Apparently, what matters more is not simply the physical distance but what can be defined as the affective distance.9

Turkey has managed to contextualize the very meaning of international aid in a way that enables it to move beyond all “distances,” specifically emotional detachment created by the established world-system of nation-states. The receiver is perceived not as “a foreign person in need of help” but as a living individual that witnesses and symbolizes the global injustice and mistaken policies of “other states” dominating the world-system. In this context, international aid has been treated as a natural part of the very meaning of Turkey itself, rather than being a mere result of strategic calculation, political alignment or expression of solidarity. It is what defines the New Turkey as a whole, from domestic politics to its vision of global politics and the self-perception of Turkish political elites. Such a perception can be seen in daily phrases and speeches delivered by the Turkish Prime Minister (PM), Deputy PM’s or NGOs in Turkey.

As poverty, inequality and humanitarian crisis continue to haunt global politics, Turkey has given a priority to development cooperation activities and humanitarian assistance

The mobilization of NGOs, direct involvement of virtually all political-official figures, re-organization of aid institutions and continuous references given to aid organizations are expressions of such political re-writing of aid activities in Turkey. It is this institutional, procedural and political deployment of “affect” that enabled Turkey to cultivate a different form of international cooperation aid that has its own peculiarities, moving beyond the limits of present international aid both in practice and procedure.

The case of Somalia and the success of Turkey is one of many examples but it receives more attention because it is a triggering case that has made the impact and effectiveness of Turkey’s international aid more visible. Furthermore, the case suggests a full framework to examine the distinguishing features of Turkish aid from other similar development cooperation.10 Nevertheless, as of 2013, Turkey has been active in more than 100 countries, ranging from Asia to Africa, the Middle East to Europe and America to the Far East.

So questions remain: What is the political history of Turkish aid? How can the success and distinguishing features of Turkey’s international development aid be explained? Is it simply another example of newcomers to the list of donor countries or is it more than that? How is the link between humanitarian diplomacy and aid maintained in the discourse of Turkish foreign policy? These are crucial questions that need to be answered in order to contextualize Turkey’s foreign aid policies.

“Foreign Aid” and International Politics

Just as Turkey’s humanitarian aid covers more than Somalia, official development assistance (ODA) itself is more than urgent humanitarian aid, which only represents one subset of ODA. Foreign aid simply refers to the flow of materials and resources in cash or in kind from a developed state to developing or less-developed nations.11 However, the form and content of what is considered official aid is as complex as international politics. To resolve such difficulty, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) provided a specific definition of ODA in 1961, which has become standardized and suggests certain criteria to distinguish between different forms of aid as the following:

“…flows to countries and territories on the DAC List of ODA Recipients and to multilateral development institutions which are provided by official agencies, including state and local governments, or by their executive agencies; and each transaction of which is administered with the promotion of the economic development and welfare of developing countries as its main objective and is concessional in character and conveys a grant element of at least 25 per cent.”12

Setting the framework for development aid, ODA includes three subsets of aid as “official development assistance, official aid and other official flows.” The first includes direct or indirect aid to the least or middle developed countries with economic development and welfare as the main objective. The second refers to aid given to multilateral development institutions and developing countries. In terms of reporting, there are certain specific requirements set by ODA eligibility, such as the exclusion of direct military aid and enforcement aspects of peacekeeping forces. The third area refers to aid that is not directly aimed at development or conveys a grant element of less than 25%. In the third framework, all activities including “projects and programs, cash transfers, deliveries of goods, training courses, research projects, debt relief operations and contributions to non-governmental organizations,” as well as humanitarian aid, meets the ODA criteria.13 Despite this clear-cut framework the ODA criteria have remained inadequate to cover all the different forms of assistance, specifically those given through and by NGOs, in parallel to transformations in international politics. In the last two decades, NGOs have developed beyond an “intermediary agent in the delivery of aid” into “a direct agent that delivers and organizes aid” on the ground,14 challenging the established framework of aid organizations particularly since the end of the Cold War.

Alongside the presence of an intense humanitarian discourse in international aid literature, there is a direct relationship between priorities in a nation’s foreign policy agenda and international aid. In other words, “realistically” and carefully crafted national interests, as a general tendency, form states’ policies and priorities on international aid. This relationship, which does not necessarily constitute a negative correlation by definition, has been well documented and the response to the relationship varies. Some have defined this as part of broader and “sinister” national interests and others have taken it as an essential expression of humanity or global responsibility. However, the necessity for aid has never been directly disputed or rejected.

Turkish aid can be contextualized as the overlapping of the geographical expansion of Turkish international assistance and strengthening of aid organizations with the rise of Turkey in the regional and global context. Rather than disputing or rejecting the relationship, Turkey has claimed to relocate the connection between politics and aid activities in a way that allows the relationship to become part of the discussion in forming a responsive new international order. One way to display this is to focus on the history of development assistance politics in Turkey, which will be discussed in the following section.

Relocating Turkey, Reorganizing Institutions

A quick glance at the history of Turkey’s institutions of development cooperation reveals a direct relationship between the strength, depth and variety of aid activities with political and economic stability and the self-defined role of Turkey in global politics. In terms of foreign aid, Akçay divides the Republican period in Turkey into three phases: 1923-1992, 1992-1999 and 1999 to now.15 As well as implying economic-political capabilities, each period reflects the depth and complexity of foreign policy options of Turkey.

The first period covered major parts of Turkey’s history and was mostly characterized by personal and temporary initiatives. Beginning in the mid-1980s, Turkey implemented aid “in parallel with DAC criteria for the first time” and began an official reorganization and planning of aid activities with the formation of the Turkish Cooperation Agency, affiliated with the State Planning Organization.16 However, both the amount and variety of aid has remained weak and there was no centralized institutional organization for the planning, coordinating and distribution of international aid until 1992.17 In this period, Turkey was absent from international aid discussions, aside from its role as a receiver country.

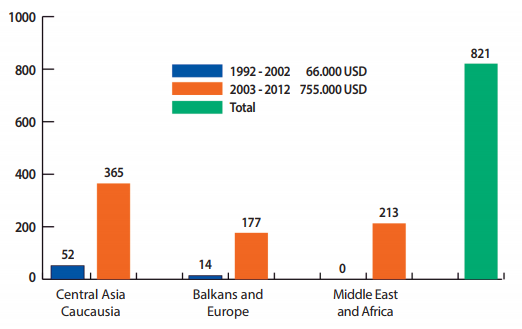

The second period, according to Akçay, began with the founding of the Presidency for Turkish Cooperation and Development Agency (TIKA), also known as the Presidency for Economic, Cultural, Educational and Technical Cooperation (EKETIP), to respond the problem of coordinating aid activities under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1992.18 Despite intentions, there was not much progress in resolving the issues and Turkish international aid during this period was mostly limited within Turkic countries of the Central Asia and Caucasia.19 Furthermore, political instability and economic crises has influenced Turkey’s international aid, which is apparent in the sudden increase in the total amount of aid in 1992, followed by a visible decrease and then irregular rise and decline in subsequent years.

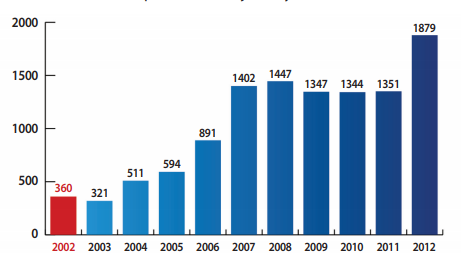

Table 1: Turkey’s International Aid (millions USD) Between 1992 and 200220

Beginning in 1992, due to the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, Turkey was optimistic that it could take an active international role. However, setting aside the discussion of such a role, political instability, economic crises and the lack of institutional structure prevented Turkey from reflecting this ambition in its international aid activities. It remained disorganized and weak both in the amount and geographical scope. Despite all the effort, TIKA had only 12 Program Coordination Office’s (POCs) and activities in merely 28 countries between 1992 and 2002.21

Akçay refers to the year 1999 as the beginning of the third period, as TIKA22 was folded into the Prime Ministry and the State Ministry for Coordination with Turkic Republics and Related Communities was appointed for the organization of all aid activities.23 While the relocation in the bureaucracy enabled TIKA to increase the variety and geographical scope of its activities, the decrease in the amount of aid continued until 2003.

The systematic and structural change in international aid politics began with the rule of the AK Party in November 2002. The governmental transition came with specific references to the role of Turkey in global politics, paving the way for developing a comprehensive cooperation strategy. The increasing role of TIKA in foreign politics, as the aid organization responsible for implementing Turkey’s development cooperation policy, in subsequent years reflects this transition, as well as the expansion of aid activities in terms of area, depth and strength. In other words, the reorganization of development-cooperation institutions and enrichment of capacities is both representative of Turkey’s transformation and a necessary-consequence of the change.

Relocating Turkey in Global Politics: “TIKA is Turkey”24

Turkey has experienced the last decade with discussions on the re-location and re-orientation of Turkey in the global political context. As stated by Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu, the claim is to maintain a transition from Turkey’s role as a “frontier country” of the Western bloc during Cold War and a “bridge country” between the East and the West during the 1990s to become aware of Turkey’s potentialities.25 According to Davutoğlu, Turkey’s role, after 2000, should be defined as “a central country with multiple regional identities that cannot be reduced to one, unified character” in the complex global political order. Turkey is identified both geographically and historically with more than one region and one culture, enabling “the country to play a central countrystatus” and find the capability to “maneuvering in several regions simultaneously.”26

As of 2013 Turkey has been active in more than 100 countries, ranging from Asia to Africa, the Middle East to Europe and Far East

This framing has been followed and realized by three-dimensional transformation in Turkey. Political consolidation and stability combined with an extensive democratization program, multi-dimensional vision of foreign politics and economic success, have been identified as three essential aspects of Turkey’s transformation in the last decade.27 Unlike previous political crises caused by coalitions or weak governments, Turkey has been under single-party rule since 2002. Turkey has witnessed a decisive democratization process with several amendments to the constitution, a referendum and the EU process. Economically, financial stability and large-scale investments enabled Turkey to become the ‘rising star’ in the region, making Turkey the 16th largest economy in the world and 6th biggest in Europe. Furthermore, Turkey paid back all its loans to the IMF in May 2013. In terms of foreign policy, Turkey has become an active stabilizing actor in both regional and global politics, reaching out to new geographies ranging from Asia to Latin America, in addition to increasing activities in Europe and the Middle East. The transformation process has been defined as the transition from the Old Turkey to the New Turkey.28 In short, Turkey has returned to the scene of global politics as a pro-active agent and development assistance organizations and NGOs have been the most active agents in realizing ambitious vision of Turkey.

Turkey has experienced the last decade with discussions on the re-location and re-orientation of Turkey in the global political context

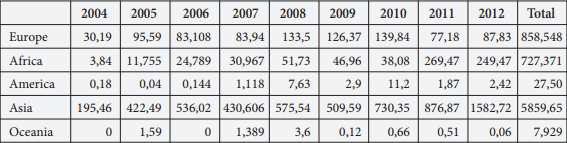

In the realm of development cooperation, the sharp increase in the activities of TIKA is a concrete sign of that transformation. As of September 2013, TIKA has implemented development projects in 110 countries from all continents and has 35 POCs in 32 countries.29 The countries in which TIKA implemented projects, ranging from Asia to Africa, Europe to Latin America and Middle East, displays the depth of geographical scope of Turkey’s aid activities.30 Likewise the number of projects has dramatically increased. The total number of projects rose to 114,47 between 2002 and 2012 from the 2241 projects implemented between 1992 and 2002, a five-fold increase in the average number of projected implemented each year. The total amount of official assistance between 2004 and 2012 (nearly $7.5 billion USD) reflects the systematic priority given to international aid in the New Turkey.31 Figure 1 displays the consistent increase in the number of projects implemented since 2002.32

Figure 1: The Number of Implemented Projects by TIKA (2002-2012)

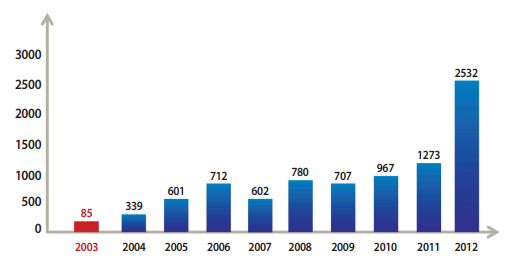

The methodical increase of Turkey’s ODA during this period gained worldwide recognition and the growth in 2011 and 2012 ranked Turkey first among OECD countries in international assistance.33 However, the increase in the amount of ODA has been a characteristic feature of Turkey’s international aid since 2003. Figure 2 displays this tendency.34

Figure 2: Turkey’s Official International Aid Between 2003 and 2012 (millions USD)

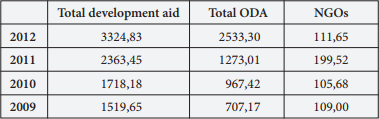

As previously stated, international assistance cannot be reduced to only ODA. Direct investments, urgent humanitarian aid and NGOs are also crucial parts of Turkey’s international aid agenda. Table 2 displays the total amount of development aid (in millions USD) in comparison to ODA since the 2009.

Table 2: Total Development Aid and ODA35

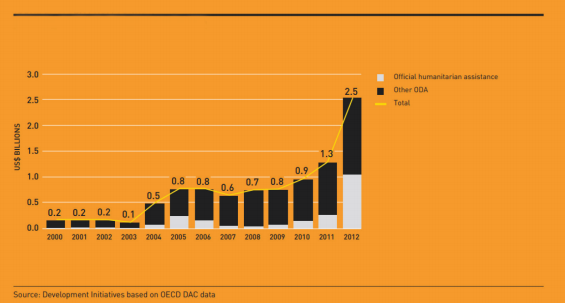

Official humanitarian assistance has been a defining feature of Turkey’s international aid activities. It increased to $1 billion USD in 2012, comprising more than 40% of Turkey’s total ODA. This increase enabled Turkey to become the 4th largest donor in humanitarian assistance and 3rd in generosity relative to Gross National Income, which is maintained by the highest increase of $775 million USD in 2012. Figure 3 provides the most comprehensive and comparative data on humanitarian assistance on a global scale.36

Figure 3: Humanitarian Assistance in Numbers

Nevertheless, the increase in humanitarian assistance is not particular to 2012, as humanitarian assistance has constituted a good portion of Turkey’s ODA since 2005 (see figure 4).37 Furthermore, TIKA has been careful to maintain a broad geographical scope in implementing its projects to refrain from limiting activities to a single region (see Figure 5).

Figure 4: ODA Flows from Turkey Between 2000 and 2012

Figure 5: Regional Distribution of TIKA’s Spending Between 2002 and 201238

A similar tendency can be seen in the regional distribution of ODA between 2004 and 2012 (see Table 3, millions USD)39

Table 3: Regional Distribution of Turkey’s Official Development Aid (millions USD)

In short, Turkey has been characterized in the last decade by a systematic focus on expanding development assistance and humanitarian aid both in geographical scope and variety. As well as the success story of Somalia, Turkey’s policy toward the Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and “open-door policy” toward Syrians since 2011 have been two prominent examples of this process.

Turkey was the first non-Western country to host the 4th UN Conference on LDCs in May 2011. The number of participants reached 10,000 with the involvement of NGOs, 36 heads of state and government, 96 ministers and 66 presidents of international organizations.40 The Conference is one of the most crucial events as it addresses the needs of 48 states, with a combined population of 900 million people, categorized as “displaying the lowest indicators of Human Development Index (HDI) measured in terms of life expectancy, literacy, standards of living and Gross Domestic Products per capita.”41 The Conference ended with the declaration of the “Istanbul Program of Action,” which determined the main pathways for the LDCs global development for the next decade. In addition to the Program, Prime Minister Erdoğan also declared Turkey’s economic and technical cooperation package for the LDCs, providing a framework and specific policies on trade, investment, education, tourism, agriculture, forestry and technical cooperation for assistance.42 It is crucial to note that Turkey pledged to provide $200 million USD annually to LDCs for technical cooperation projects and programs but has already exceeded that pledge by spending $359.91 million USD in 2012.43

The second case, the open-door policy toward Syrians, is another aspect of Turkey’s humanitarian assistance, which has been praised by representatives of several international organizations and NGOs.44 As of January 2014, the number of Syrians in Turkey has reached 700.000, with over 200,000 refugees living in 21 accommodation centers, known as Temporary Protection Centers (TPCs), run by the Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency (AFAD). All Syrians have access to free health services and their major needs, including education, are being met in the TPCs through the coordination of AFAD. Approximately 62,000 refugees have attended educational courses, including primary education and the total number given ambulatory care service has reached 2.1 million. It must be noted that Turkey has spent more than $2 billion USD and only received $140 million USD in external aid since 2011.45

Turkey: Conscience of Global Politics

On September 26th 2013, while speaking at the World Humanitarian Summit of the 68th UN General Assembly, the UN Secretary General praised Turkey’s international assistance and declared that Turkey will host the first World Humanitarian Summit in 2016. The Summit is defined as “a multi-year process, starting next year with regional consultations that will ask all actors to discuss how humanitarian work is conducted, how we can improve delivery for those in need.”46 Turkey’s Foreign Minister welcomed the declaration and defined the Summit as “the most meaningful one to be held in Turkey.” Hosting the first World Summit on Humanitarian Assistance, following the 4th UN-LDC Conference, is another historic milestone that displays Turkey’s key international assistance role. In that sense, Turkey has become an indispensable partner and leading country on a global scale in providing contributions to fight against humanitarian crises, poverty and global injustice.

Turkey’s new role is a consequence of the strategic priority given to international assistance in the last decade and the material success maintained through the activities of official and civil aid organizations. The leading role of Prime Minister Erdoğan has been one of the most constitutive effects in this transition. The majority of aid campaigns, particularly for Somalia, Myanmar and Syria, have been directly launched and followed by the Prime Minister himself. The first announcement of these campaigns was put on the website of the Prime Ministry as an official call to raise awareness of suffering in different parts of the world. In addition to continuous references and support to aid organizations that represent Turkey’s soft power,47 virtually all international forum and summits, such as the UN General Assemblies, Organization of Islamic Cooperation meetings and international conferences, have been used as platforms to increase awareness of the necessity of international assistance to maintain global justice. Certain themes have been continuously referred to in virtually all speeches delivered on these platforms, as well as in domestic politics, including need for justice, links between world order and poverty (UN and leadership failure), need for a new world order, and empathy. 48 Furthermore, in addition to the coordinating function of TIKA, a specific Deputy Prime Minister is appointed to monitor the implementation of each major aid campaign, with participation of all affiliated institutions and representatives of relevant ministries, such as AFAD, Kızılay, the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Education and so on.49

TIKA drills hundreds of water wells across Africa. / AA

TIKA drills hundreds of water wells across Africa. / AA

The most striking theme apparent in all these activities has been the direct reference to the historical, cultural and political values that believed to identify Turkey. Humanitarian assistance has been defined as a natural and indispensable part of Turkey’s identity, rooted in a long historical tradition, which is viewed as paving the way for the foundation of a new global order by reviving the long-forgotten legacy of Turkish identity.

Furthermore, maintaining regional and global stability has been directly associated with development cooperation targeting to reduce poverty and preserve sustainable global development in Turkish foreign policy. In that sense, expanding the geographical scope and increasing the amount and variety of official aid has been an indispensable part of Ankara’s pro-active foreign policy.50 On the one hand, this universal perspective of aid policy has a globalizing effect on both NGOs and official institutions. On the other hand, the policy is a consequence of such a tendency in Turkish foreign policy-makers. These organizations, which previously had limited activities by either focusing on a specific region or on domestic aid campaigns, have made different parts of the world, from Central Asia to sub-Saharan Africa or the Middle East and Europe, part of their daily discussions and activities.51

Expanding the geographical scope and increasing the volume of official aid is an indispensable part of Ankara’s pro-active foreign policy

In that sense, the main theme of the 5th Annual Ambassadors Conference in 2012, “Humanitarian Diplomacy” (HD hereafter), was an expression of Turkey’s position in the international politics. HD, in Turkey’s perspective, meant to be a vision beyond humanitarian aid, aiming at developing “a new language of diplomacy in policy areas related to the future of the whole of humankind”.52 In the final declaration of the Conference, the following reason was given for selecting this theme:53

“Humanitarian diplomacy reflects the compassionate and competent character of the Republic of Turkey and depicts the human oriented nature of our foreign policy which merges our interests with our values. Turkish foreign policy takes human dignity as a point of reference and remains determined to use all its means and capabilities in this direction. In this regard and in light of the historical transformation taking place in our immediate neighborhood, the deliberations in the Conference has confirmed the need for Turkey to continue to implement humanitarian diplomacy in an effective and decisive way in a broad geography stretching from Syria to Afghanistan and Myanmar to Somalia in the forthcoming period. … It was also confirmed that Turkey cannot be indifferent to the developments taking place in the southern and northern basins of the Mediterranean, with which it enjoys special ties stemming from history.”

In his inaugural speech, Foreign Minister Davutoğlu defined HD as a constitutive part of the vision suggested by Turkey, which stemmed from political values embodied by Turkey in global politics. Relying on historical traditions and the cultural heritage of the country, HD is an essential expression of Turkey’s role, identity and quest for justice in international politics. The three dimensions of Turkey’s HD, elaborated by Davutoğlu, policies toward citizens of Turkey, policies toward crisis zones regardless of geographical proximity and policies concerning structures of global order, are representations of such framing of Turkey’s role in the global transformation of international politics.54 First, Turkey’s HD is presented as a model to explain virtually all activities in foreign policy, ranging from visa liberation policy to the opening of new embassies, involvement with humanitarian assistance to maintaining positive civilian-state relations, being pro-active during times of crisis and taking responsibility in international organizations such as UN. Second, it is defined as a framework developed by Turkey to move beyond diplomatic models and humanitarian visions formed by the Westphalian nation-state model.55 This is why Davutoglu defined the essence of Turkey’s national identity as being a “nation-in movement,” enabling Turkey to have a multi-dimensional identity stemming from historical encounters, from the East to the West or from the South to the North. Through this global framing of identity, Turkey’s HD relies on a perspective that does not differentiate between citizens and the people with whom Turkey shares a common history and looks for more inclusive and representative international order, “reflecting the will of all participants”.56 The new formulation suggested in these speeches is defined as a “grand restoration” of identity, culture and political self-perception adjusted to the political space of global politics.57 In that sense the affective-distance created by the Westphalian model of international order is surmounted by a globalized vision derived from re-defining of Turkey’s identity and role.

Turkey’s development cooperation has been established on the basis of re-locating of national-identity, critique of the established world system, re-description of international politics and the march of Turkey into the political space of a globalized world. The material success characterizing Turkey’s official aid and humanitarian assistance is both a consequence and representative of the complex relationship between these themes. Turkey has won the hearts and minds of people through this systematic and dedicated vision of humanitarian aid and official assistance, as it has been treated as the only way to respond to the suffering of others and move towards a just global order.

Endnotes

- In February 2012 the then chairman of OECD/DAC Brian Atwood offered membership to Turkey in the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) and in October 2013, Erik Solheim, the present chairman of OECD/DAC, renewed the invitation, and stated that “Turkey’s steps in Somalia may set an example for other DAC member countries. It would be useful for us to have Turkey on DAC’s executive committee.” http://www.haber7.com/ic-politika/haber/1083599-zenginler-kulubu-turkiyeyi-ikna-etmeye-calisiyor. http://www.tr.undp.org/content/turkey/en/home/presscenter/news-from-new-horizons/2012/05/turkey-is-on-the-way-of-OECD-DAC-membership/

- Kyle Westaway “Turkey is poised to cash in on a stable Somalia.” http://qz.com/124918/turkey-is-poised-to-cash-in-on-a-stable-somalia. September 17, 2013.

- Hassan Sheikh Mahmoud, Speech delivered at CSIS “The Future of Governance in Somalia.” http://csis.org/files/attachments/130117_HassanSheikhMahamud_transcript.pdf. 17 January 2013, pp. 18-19.

- For some readings on Turkey-Somalia relationship see Amal Ahmad, “Understanding Somalia.” http://www.opendemocracy.net/amal-ahmed/understanding-somalia. April 1, 2013. Osman Jama Ali and Mohamed Sharif Mohamud. “Only Turkey is showing solidarity with Somalia’s people.” http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2012/jan/26/un-somalia-crisis. January 26, 2012. Pinar Akdemir. “Turkish aid to Somalia: A new pulse in Africa.” http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2011/08/20118288361981885.html. September 2, 2011. Abdi Ismail Samatar. “A new deal for Somalia: How can it work.” http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2013/10/a-new-deal-for-somalia-how-can-it-work-20131021392150694.html. October 12, 2013. Alpaslan Özerdem. “How Turkey is emerging as a development partner in Africa.” http://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2013/apr/10/turkey-development-partner-africa. April 10, 2013. Ahmed Ali. “Turkish aid in Somalia: the irresistible appeal of boots on the ground.” http://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2013/sep/30/turkey-aid-somalia-aid-effectiveness. September 30, 2013. Julia Harte. “Turkey Shocks Africa.” World Policy Journal. vol. 29 , no. 4, Winter 2012 - 2013, p. 27-38. J. Campbell “Turkeys love affair with Somalia.” http://blogs.cfr.org/campbell/2012/11/07/turkeys-love-affair-with-somalia. November 7, 2012. The distinctive features and the impact of Turkey’s humanitarian assistance toward Somalia has been subject of positive comments with specific references to the success, influence and peculiarities of Turkish policy. The following comments display the general tendency of readings on Turkey’s initiative: “Somalia, a dead country brought back to life, by the Turks”, “They have done differently, to win over the hearts of the people of Somalia.” “One country, Turkey, has responded in a unique manner, demonstrating solidarity with the people of Somalia.” “The Somali people wholeheartedly appreciate this act of bravery and nobility” “What can be learned from the Turkish initiative is that when you provide sincere assistance directly and immediately to those who are most in need, you gain the hearts and minds of the people.” “More than any other country, Turkey has taken on a deeply influential role in bringing Somalia’s situation to international attention.”

- Alongside previous incidents, staff building of Turkey’s embassy in Mogadishu was subject of a deadly attack on 27 July 2013. http://www.aa.com.tr/en/s/208997--c

- Prime Minister Erdogan, accompanied by his wife, children, and a large delegation of ministers, journalists, celebrities and representatives aid organizations, composed of more than 300 people, visited Mogadishu on 29 August 2011 and became the first leader in the last 20 years visiting Somalia. Right after the visit, in November, Turkey has become the first non-African country by reopening the embassy in the city and in March 2012 Turkish Airlines has begun direct flights from Istanbul to Mogadishu, again, became the first major commercial airline in the last 20 years has landed at Mogadishu airport. Since the visit, Turkey have been assisting Somalia in all sectors, from health services to infrastructure and education. A documentary, “Somalia after two years,” provide a complete coverage of Turkey’s projects in Somalia, see http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iM6ZIrNqHHw. The documentary covers all aid activities by the Government and all NGO’s since August 2011. Regarding the security concerns PM Erdoğan has been quite clear: “By re-opening of our Embassy in Mogadishu, we have also showed the world that claims of security challenges cannot be an excuse for delaying assistance” said in September 22, 2011 in his speech delivered to the 66th session of the UN General Assembly, by which the world’s attention is taken to Somalia. http://gadebate.un.org/sites/default/files/gastatements/66/TR_en.pdf

- Abdi Aynte, “Türkiye-Afrika İlişkileri Ankara’da Tartışıldı” http://kdk.gov.tr/faaliyetler/paneller/turkiye-afrika-iliskileriortak-kaderortak-gelecek/124. 07 February 2013. For Turkey’s opening to Africa see http://kdk.gov.tr/sayilarla/afrika-acilimi/11

- TIKAvizyon. “TİKA Faaliyetleri ve Resmi Kalkınma Yardımları,” No.1 (August 2013), p. 4.

- The term “affect” here is used to describe complex set of relationship between actions or behaviors and emotions, values and feelings, the former being characterized and formed by the latter. Minister of Foreign Affairs Davutoğlu referred to “hemhal olmak” (being fellow in emotions and feelings) as one of the defining feature of Turkish humanitarian assistance, which will be discussed in the last section. In such a framework, “affective distance” refers to the relationship maintained between Westphalian system of nation-state and individual-political awareness or blindness toward suffering of “foreigners”. The established forms of politics in the constellation of nation-states create structural obstacles toward nourishing emotions, values or feelings conducive to such awareness on the global scale, with the exception of depoliticizing humanitarian discourse. For related speech by Davutoğlu see http://www.mfa.gov.tr/disisleri-bakani-sayin-ahmet-davutoglu_nun-yeni-atanan-baskonsoloslara-yonelik-hitabi_-28-haziran-2013.tr.mfa

- http://www.mfa.gov.tr/disisleri-bakani-sayin-ahmet-davutoglu_nun-v_-buyukelciler-konferansinda-yaptigi-konusma_-2-ocak-2013_-ankara.tr.mfa

- See all references in endnote 3.

- Engin Akçay, Bir Dış Politika Enstrümanı Olarak Türk Dış Yardımları, (Ankara: Turgut Özal Üniversitesi Yayınları , 2012), p. 7.

- For summarized info on distinguishing features of ODA see OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) “Is it ODA.” OECD Publishing, Paris, 2008, p. 1.

- OECD, (DAC). “Glossary of statistical terms,” OECD, Paris. 2007

- Akçay, Bir Dış Politika Enstrümanı Olarak Türk Dış Yardımlar, p. 16.

- Akçay, Bir Dış Politika Enstrümanı Olarak Türk Dış Yardımları, p. 63

- It must be noted that Turkey is both a recipient of ODA and a donor country and officially Turkey’s international aid programme is launched on June 5th1985 with a “comprehensive aid package worth 10 million USD, destined towards institutional capacity building in Gambia, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Mauritania, Senegal, Somalia, and Sudan.” In the realm of capacity building and technical assistance TAC’s involvement continued until the late 1990s. see http://www.mfa.gov.tr/turkey_s-development-cooperation.en.mfa

- Akçay, Bir Dış Politika Enstrümanı Olarak Türk Dış Yardımları, pp. 65-67.

- EKETIP is proto-form of TIKA founded under ministry of Foreign Affairs has been responsible from development aid with priority given to Turkic countries. It must be noted that alongside TIKA, AFAD (established in 2009, Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency) and Turkish Crescent (established in 1868, the largest humanitarian organization in Turkey) have influential role in realizing Turkey’s international-humanitarian aid, particularly in the case of emergencies. However, TIKA is responsible for implementing Turkey’s development and aid cooperation policy with national actors, international organizations. Further to that TIKA is also accredited to collect and report ODA statistics of Turkey. Therefore telling the story of Turkey’s international aid policy is to tell the story of TIKA. For a brief reading see http://www.mfa.gov.tr/turkey_s-development-cooperation.en.mfa

- Akçay. Bir Dış Politika Enstrümanı Olarak Türk Dış Yardımları. pp. 73-76

- Akçay. Bir Dış Politika Enstrümanı Olarak Türk Dış Yardımları. pp. 73, 76, 79. Until the early 2000 Turkey’s international assistance has suffered from collecting proper data of the amount of aid. Relying on official sources Akçay’s study provide the most comprehensive data beginning from 1990s.

- “TİKA Faaliyetleri ve Resmi Kalkınma Yardımları,” No.1 (August 2013), p. 4.

- Alongside coordination and reporting of development assistance, fighting against poverty, maintaining sustainable development, capacity sharing, technical assistance, cultural cooperation, protecting and restoring cultural and historical legacy of Turkey and capacity building are described as main tasks of TIKA. “TİKA Faaliyetleri ve Resmi Kalkınma Yardımları,” August 2013, p4.

- Akçay, Bir Dış Politika Enstrümanı Olarak Türk Dış Yardımları, p. 78.

- “TIKA is Turkey” is a frequently used phrase by all political elites in Turkey for describing all types of development cooperation, capacity buildings and aid activities of Turkey. The first usage of the phrase is unknown but since mid 2000 it became quite popular from Balkans to the Middle East and Africa. For related stories see http://kdk.gov.tr/haber/bekir-bozdag-ve-cevdet-yilmaz-somalide/226

- www.haberturk.com/dunya/haber/856320-gazzede-insan-olmak www.haberturk.com/dunya/haber/

823798-somalide-turk-mucizesi - Deputy Prime Minister Bekir Bozdağ, in charge of TIKA, told the press that he heard the phrase for the first time from a woman in Macedonia, during an opening ceremony. “When she was asked what TIKA is by her child, she replied: TIKA is restoring our mosques, give scholarship to our children. TIKA is Turkey.” http://www.tika.gov.tr/haber/tika-turkiyedir/457

- Ahmed Davutoğlu, “Turkey’s Foreign Policy Vision: An Assessment of 2007,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 10. No. 1. (2008), pp. 77-80.

- Ahmed Davutoğlu, “Turkey’s Foreign Policy Vision: An Assessment of 2007.” p. 78.

- For a comprehensive reading on the last decade of Turkey in foreign politics see İbrahim Kalın (ed.), 2000’li Yıllar: Türkiye’de Dış Politika. (İstanbul: Meydan Yayıncılık, 2011) and Cemal Haşimi (ed.), 2000’li Yıllar: Türkiye, Avrupa ve Avrupa Birliği. (İstanbul: Meydan Yayıncılık, 2011). The series entitled as “2000’li Yıllar” consists of 10 edited studies covering the last decade of Turkey with different focus, ranging from economy to culture, democratization, law, education, media and political parties and identities. See http://www.2000liyillar.com/kitaplar.htm

- See the firs annual conference of Insight Turkey: Debating New Turkey held in Washington DC in 2010. http://www.insightturkey.com/first-annual-conference-debating-new-turkey/events/173

- “TİKA Faaliyetleri ve Resmi Kalkınma Yardımları,” No.1 (August 2013), p. 4.

- Implemented projects include technical assistance and cooperation, programme assistance, education (training and providing educational materials, school construction and renovation), health sector improvements (hospital construction and renovation, providing medical equipments and materials, surgical operations, vaccination campaigns), water and sanitation, improvement of public and civil infrastructure, cultural cooperation, restoration activities, housing, and agricultural projects (providing equipment and technical support). For a full list of activities see http://www.tika.gov.tr/en/fields-of-activity/2 and for a detailed list countries see TİKAvizyon paper but some of these countries are as following: Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Turkmenistan, Pakistan, Bhutan, Estonia, Romania, Greece, Benin, Bostvana, Cibuti, Ethiopia, Nijer, Hungary, Cuba, Vanuatu, Sierra Lione, Palestine, Egypt, Madagaskar, Mauritania, Togo, Eritrea and etc.

- “TİKA Faaliyetleri ve Resmi Kalkınma Yardımları,” No.1 (August 2013), pp. 6-7.

- “TİKA Faaliyetleri ve Resmi Kalkınma Yardımları,” No.1 (August 2013), p. 6.

- “TİKA Faaliyetleri ve Resmi Kalkınma Yardımları,” No.1 (August 2013), p. 13.

- “TİKA Faaliyetleri ve Resmi Kalkınma Yardımları,” No.1 (August 2013), p. 13.

- The statistics provided by TİKA Presidency and it must be noted that the data refers only assistance met with ODA criterion. Numerous NGOs have been crucial part of Turkey’s humanitarian assistance and several NGOs such as Humanitarian Relief Foundation, Kimse Yok mu, Cansuyu, Yeryüzü Doktorları, Yardımeli, have managed to maintain a global outreach in their activities.

- Global Humanitarian Assistance Report, 2013, p. 4. GHA provides the most comprehensive up-to-date data for global humanitarian assistance. http://www.globalhumanitarianassistance.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/GHA-Report-20131.pdf. It is crucial to note that Turkey maintained such an increase in 2012 despite the worldwide tendency to reduce urgent humanitarian aid.

- Global Humanitarian Assistance Report, 2013, p. 37.

- “TİKA Faaliyetleri ve Resmi Kalkınma Yardımları,” No.1 (August 2013), p. 8.

- “TİKA Faaliyetleri ve Resmi Kalkınma Yardımları,” No.1 (August 2013), p. 15. Then, here it must noted that the perception of Turkey’s international assistance as being concentrated on small number of states such as Pakistan, Syria and Somalia, at the expense of others is mostly related with urgent humanitarian aid. It does not adequately provide a comprehensive picture of Turkey’s policy of international assistance.

- See http://www.ldc4istanbul.org/

- http://www.ldcwatch.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=2&Itemid=27&

lang=en - For Istanbul Declaration see http://ldc4istanbul.org/uploads/IPoA.pdf and for Turkey’s economic-technical package for LDCs see http://ldc4istanbul.org/uploads/special_supplement120511.pdf

- “TİKA Faaliyetleri ve Resmi Kalkınma Yardımları,” No.1 (August 2013), p. 15.

- For some examples www.aa.com.tr/en/news/236474--un-praises-turkey-s-effort-on-syria-refugees

- http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/un-chief-visits-camps-and-praises-turkey.aspx?pageID=238&

nID=36378&NewsCatID=338 - http://english.cntv.cn/program/asiatoday/20130313/100060.shtml

- http://english.sabah.com.tr/national/2013/09/12/pm-erdogan-islamophobia-is-a-crime-against-humanity

- See http://www.aa.com.tr/en/news/233245--turkey-to-host-first-ever-world-humanitarian-summit-in-2016

- see http://www.akparti.org.tr/english/haberler/ak-party-group-meeting-november-23-2010/25713 and http://www.haberturk.com/dunya/haber/661358-stklarla-somaliyi-degerlendirdi

- Recep Tayyip Erdogan. “Tears of Somalia” Foreign Policy. (October 10 2011). http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2011/10/10/the_tears_of_somalia

- For some of these speeches, see http://www.ldc4istanbul.org/uploads/newsletter2.pdf http://gadebate.

un.org/sites/default/files/gastatements/66/TR_en.pdf - http://www.thenewturkey.org/erdogan-a-new-order-of-justice-is-needed/new-world/1317

- http://www.akparti.org.tr/english/haberler/ak-party-group-meeting-november-23-

- http://www.akparti.org.tr/english/haberler/ak-party-group-meeting-october-9-2012/32934

- http://www.haberturk.com/gundem/haber/784951-basbakandan-onemli-aciklamalar

- http://news.gmu.edu/articles/2417

- https://www.afad.gov.tr/EN/HaberDetay.aspx?ID=5&IcerikID=911

- http://kdk.gov.tr/haber/basbakan-yardimcisi-bozdag-ankara-somaliye-2-yil-once-bugun-ses-vermisti/284

- Here it must be noted that in 2011 “Turkey provided development assistance to 131 countries that appear on the OECD/DAC list of aid recipients” and implemented a “demand-driven aid policy.” http://www.mfa.gov.tr/turkey_s-development-cooperation.en.mfa

- See the latest news: “Eid al-Adha campaigns of Turkish foundations and associations attract attention all around the world from Turkey to Asia, Africa, Balkans, and Far East.”

- http://www.aa.com.tr/en/s/241036--turkish-eid-reliefs-reach-over-2-5-million-families

- Ahmet Davutoğlu “Turkey’s Humanitarian Diplomacy: Objectives, Challenges and Prospects,” Nationalities Papers: The Journal of Nationalism and Ethnicity, Vol. 41. No. 6 (2013), pp. 866.

- The conference is one of the most crucial events for Turkey’s foreign policy as being held with the participation of all ambassadors, it functions as a platform to discuss and determine the main strategies of Turkey in global politics. See final declaration of the conference: http://www.mfa.gov.tr/final_declaration_of_the_fifth_annual_ambassadors_conference.en.mfa

- Ahmet Davutoğlu “Turkey’s Humanitarian Diplomacy,” pp. 866-870.

- http://www.mfa.gov.tr/disisleri-bakani-sayin-ahmet-davutoglu_nun-v_-buyukelciler-konferansinda-yaptigi-konusma_-2-ocak-2013_-ankara.tr.mfa

- Ahmet Davutoğlu “Turkey’s Humanitarian Diplomacy,” pp. 868.

- http://www.mfa.gov.tr/disisleri-bakani-sayin-ahmet-davutoglu_nun-yurtdisi-vatandaslar-danisma-kurulu-toplantisi_-17_06_2013.tr.mfa

- http://www.mfa.gov.tr/disisleri-bakani-ahmet-davutoglu_nun-diyarbakir-dicle-universitesinde-verdigi-_buyuk-restorasyon_-kadim_den-kuresellesmeye-yeni.tr.mfa