Introduction

Although the origins of the concept of feminism are not very old, feminist ideas date back to the Ancient Greek and Chinese civilizations. Christine de Pisan’s Book of the City of Ladies, published in 1405 in Italy, expressed many ideas of feminism by arguing for women’s political action and right to education. Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, written after the French Revolution, is regarded as the first modern feminist text. In the mid-19th century, the women’s movement became a major focus of interest and women made more efforts to win the right to vote. In this period, called first-wave feminism, women managed to gain this particular right and assumed that they would win all the other rights as well.1

In post-Cold War Europe, religion and gender relations have been at the heart of many transformative processes, including migration, cultural pluralism, bioethical debates, and demographic change, which creates challenges for theories of secularization. There are contradictions between the right to lead a religious life and women’s rights conceived as equality between genders. Feminist research has often neglected religious women, while research on religious inclusion has neglected women. Since the beginning of the 21st century, scholars and policymakers have begun to advocate for collective state approaches to religious pluralism and to apply policies tackling religious and gender inequalities.2

Debates on gender take on a new dimension in the context of the principle of laïcité. In the case of France, it is necessary to speak of collusion between feminist discourse, discourse on laïcité, and discourse on the Republic as the French paragon of emancipation. In fact, the public debate which led to the construction of a close relationship between laïcité and the equality of the sexes, which must be protected from any intrusion of cultural difference, became institutionalized in the work of the Senate delegation on women’s rights.3 Several feminist scholars, including Patel,4 Badinter,5 and Varma, Dhaliwal, and Nagarajan,6 argue that the French understanding of laïcité is the best way to achieve gender equality. They argue that granting political power to religious organizations enshrines gender inequality through state support for religious-cultural practices that harm women (e.g., female genital mutilation, polygamy, forced marriage, a ban on contraception and abortion) and ensures state funding for fundamentalists posing as moderates. Other researchers, such as Reilly and Toldy,7 believe that the concept of laïcité is a bad political solution for religious people because it excludes them from the political and public sphere; for example, by withholding funds for social and educational services based on religious affiliation, by prohibiting the wearing of religious symbols in public space or by prohibiting ‘religious arguments’ in political debates.

Muslim women themselves, both French and migrant, appear not only as symbols of ‘the oppression of women in Islam,’ but also as the main threat to gender equality, allegedly accomplished in Europe

Gender equality and the emancipation of women are thus brought into the debate as to if they were factual realities in European societies. Muslim women themselves, both French and migrant, appear not only as symbols of ‘the oppression of women in Islam,’ but also as the main threat to gender equality, allegedly accomplished in Europe. In the instrumentalization of the argument of equality, the appeal to the principle of laïcité serves to stigmatize ‘the practices of the veil’ and to exclude the veiled Muslim women from republican institutions. In spite of ideological differences in Europe, there is a unanimous consensus between left and right politicians on the need to ‘save veiled women oppressed by Islamic rule’ and, more specifically, by men close to them.8 Some French feminists, such as Caroline Fourest, continuously argue that there is no gender equality in Islam, and depict the veil as a symbol of oppression for Muslim women. For them, Islam contradicts the principle of laïcité in which the veil has no place in the public sphere. In the French press, the weekly Marianne magazine comes to the forefront in terms of endorsing such arguments very frequently, assisting in the reproduction of anti-Muslim rhetoric in France.9

Gender equality is interpreted as an effective norm of Western modernity that Islam is called upon to respect. The normative interpretation of gender equality thus founds the distinction between ‘the modern nation’ and ‘backward’ Muslims.10

From time to time, Muslim women are placed at the center of French public debates where they are targeted due to their way of life. The burkinis or sports hijabs they wear are demonized, they are forbidden to wear the veil when accompanying their children on school trips; the anti-veil discourse thus, somehow legitimizes different forms of discrimination against Muslim women.11 In fact, the ‘veil business’ in France goes well beyond the realm of school. On the extracurricular playing field, in private nurseries, on public beaches, in sports competitions –in other words, in everything and everywhere that involves a public presence– the veil, as a sign visible and recognizable to the eyes of all that its wearer adheres to the Muslim faith, is forbidden. Within the context of France’s prohibitive legislative, administrative and regulatory arsenal, wearing the veil or any other sign reminiscent of the veil and the fact of being a practicing Muslim woman –‘declared’– appears as evidence against her capacity for responsibility, professional and sporting competence or the ability to take care of her children or those of others, etc.

To mention a few examples, the ‘Baby Loup’ case began in 2008 when an employee working at a private nursery was required to remove her burqa.12 Later in March 2010, Ilham Moussaïd, an activist wearing the veil, became a legislative candidate in Vaucluse on the far-right New Anti-Capitalist Party’s (NPA) list, which sparked controversy and criticism; Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the leader of a far-left party, stated that a veiled woman could not ‘represent everyone.’ Therefore, it is ‘a mistake’ to present a veiled woman in a public election. In October 2010, a law prohibiting the concealment of the face, implicitly targeting the wearing of the burqa or niqab, was passed. A year ago, the President of the Republic affirmed before a Congress meeting in Versailles that “the burqa is not welcome on the territory of the Republic.”13 He thus contributed to formally establishing punitive rhetoric targeting veiled Muslim women. In 2012, Luc Châtel, then Minister of National Education, signed circular prohibiting veiled women from accompanying their children on school outings. Finally, in 2016, the ‘Burkini affair’ broke out, in reference to the various municipal decrees published during the summer to ban from public beaches the wearing of this swimsuit covering the entire body of Muslim women.14

According to the Stasi Report, the principle of laïcité had a double requirement: state neutrality on the one hand, and protection of freedom of conscience on the other

This study aims to explore anti-veil and anti-burqa laws in the French public sphere. Methodologically, it uses discourse analysis of content provided by mainstream feminists. Most of the academic research on this topic is written in the French language. In this respect, the present analysis contributes to English-language scholarship and to anti-veil discussions in France.

Gender, the Public Sphere and Laïcité

Laïcité and the Public Sphere

Laïcité has been a central theme of public debate for the past twenty-five years in France, and in French-speaking Belgium and Quebec. The ‘French-speaking’ aspect of this debate is not due to chance; the idea of ‘laïcité refers to a universal problem (the relationship between religion and politics in a given society) but has taken on a specifically French form that has influenced some countries in the same ‘linguistic-cultural’ sphere. One might think that the debate on laïcité is the translation, within the framework of this “French-speaking cultural area,” of the debate on ‘identity,’ which has crossed all of Europe since the end of the Cold War. The disappearance of the Eastern Bloc and the resurgence of national identities in the context of capitalist globalization enabled the redefinition of ‘we’ vs. ‘others,’ which concerns not only Europe but the whole Western world.15

In December 2003, the Stasi Commission responsible for reviewing the concept of secularity widely extended its application. According to the Stasi Report, the principle of laïcité had a double requirement: state neutrality on the one hand, and protection of freedom of conscience on the other. The difficulty of translating the principle of laïcité into law was explained by the tension between these two poles –the neutrality of the secular state and religious freedom– which were in no way incompatible but nonetheless potentially contradictory.16

Two years later, the celebration of the centenary of the 1905 French law on the Separation of Church and State in France relaunched the debate on laïcité, which was no longer of interest only to specialists in various disciplines (history, law, philosophy, sociology) but also to a wider public audience. Laïcité has been widely discussed in France for the past fifteen years, particularly after Muslims became more visible in the French public sphere. Indeed, very different conceptions have been proposed, sometimes leading to different, even opposite, consequences. Everyone interprets laïcité freely according to their situation, needs, or demands.

The multitude of studies devoted to tackling laïcité, in fact, has blurred this notion instead of clarifying it. Laïcité has never been a simple and clear idea, easily understandable and applied in practice. Rather, it keeps being used as a vague and flexible concept with extensible and variously interpretable content. The term laïcité itself is actually very confused. It refers either to the separation of the state from religion or to the state’s neutrality in religious matters. But the concept of laïcité has been ‘enriched’ by attributing a more substantial content to it and giving it a very broad extension. This is a general trend that has been expanding over the past fifteen years, to the point of becoming dominant and even exclusive. It consists of using the term laïcité to refer to diverse notions more or less linked to it but certainly different from it, such as freedom of conscience and religion, tolerance, pluralism, equality, democracy, etc. A positive content and a concrete aspect are also attributed to laïcité so as to make it attractive and mobilizing. However, while claiming to defend and promote laïcité, this approach is likely to ignore, transform or even dismiss it surreptitiously.17

Maclure and Taylor make a distinction between two models of laïcité depending on the place given to religion in the public sphere. While the rigorous republican model (France) insists on a strict separation between the state and religion by restricting religious affiliations to the private sphere, the more flexible and open liberal pluralist model perceives laïcité as a political form of governance that must find an ‘optimal balance’ between respecting citizens’ moral equality and respecting their freedom of conscience. Thus, the republican model expects individuals to be neutral and avoid displaying any religious symbol in the public sphere; the pluralist liberal model demands neutrality only from institutions, not individuals.18 Liberal laïcité is, therefore ‘welcoming’ to religious beliefs and considers that religious beliefs are individual rights and, as such, cannot be penalized. As for republican laïcité, it adheres to the principle of separation and neutrality, but it adds an element: a form of hostility in principle toward religious belief. From this point of view, one could say that ‘religious belief’ is more ‘tolerated’ than accepted: it is not legitimate to prohibit a belief as such, but it is legitimate to suspect it a priori; the ideal defended by republican laïcité remains that of a world without religion.19

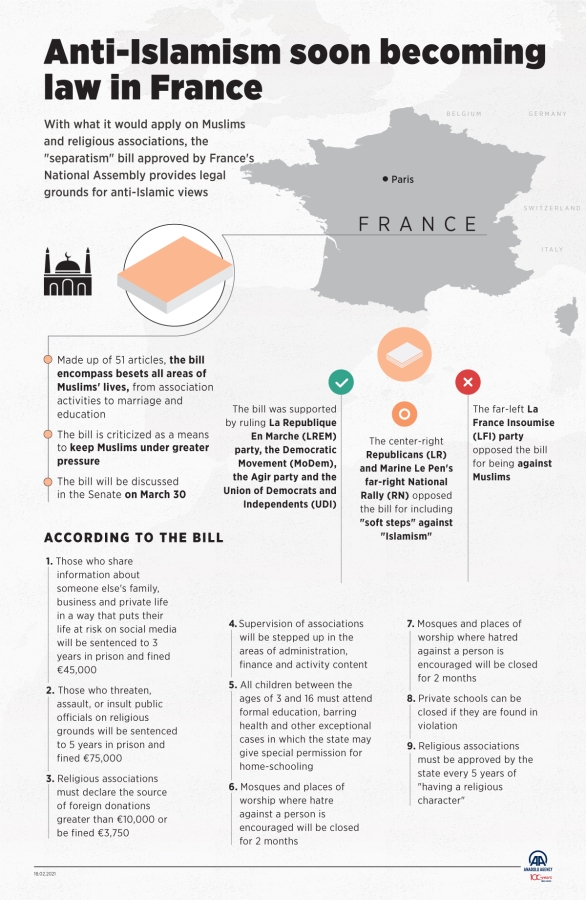

“Anti-Islamism Soon Becoming Law in France” infographic summarizes what it would apply to Muslims and religious associations through the ‘separatism’ bill approved by France’s National Assembly. MAIMAITIMING YILIXIATI / AA

The two conceptions view the question of the private or public sphere differently. In liberal laïcité, the idea that religion is a private matter is entirely contained in the principle of separation and neutrality. Religion is not ‘in’ the ‘public sphere,’ in the sense that the state can neither endorse religion nor differentiate between citizens on the basis of religion. The ‘public sphere’ is what imposes itself on everyone; it is namely the sphere of public authority. But republican laïcité considers everything that is done in public, that is to say, anything ‘in public,’ with the knowledge of others, to be ‘public.’ As Jean Baubérot points out, it thus confuses the ‘private’ sphere with the ‘intimate’ sphere. To confine religion to the private sphere thus defined can, then, amount to suppressing all freedoms of expression. Because by definition, expressing yourself is a public act. Speaking only when you cannot be seen by others is obviously not freedom. The freedom to express yourself in your cellar is quite simply the prohibition against expressing yourself. On this point, republican laïcité, in its radical forms, contradicts Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which says that everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion; this right implies the freedom to change religion or belief, as well as the freedom to profess one’s religion or belief alone or in common, both in public and in private, through education, practices, worship and achievement rites.20

Colonial Mentality, Gender Questions, and Visibility

The Emancipation of Women and the Heritage of Colonialism

In France, the “defense of laïcité” in the name of women’s rights, which has crystallized in the debate around the question of the veil, dates back to the 1990s. Feminism and religion can be considered incompatible, even antagonistic, particularly in a state that wants to be ‘secular,’ although there are many individuals and groups that claim to be both religious and secular. France’s pro-secular posture, however, seems to be applied more strictly to certain religions than others, to Islam in this case, to the detriment of Muslim women.21 Early feminists questioned the distinction between the public and private spheres. The private sphere, idealized by the notion of home, denigrates and endangers women in part by isolating them and submitting them to the control of men, including through domestic violence. Raia Prokhovnik states that feminist critics view the public-private divide itself as “the source of the oppression of women.”22 This dichotomy has ancient roots in Western thought as a binary opposition that is used to subsume a wide range of other important distinctions. According to Joan Landes, feminists did not invent the vocabulary of the public and the private which, in ordinary language and political tradition, are intimately linked. The term ‘public’ suggests the opposite of ‘private’: concerning the people as a whole, the community, the common good, things open to view, and things accessible and shared by all. Conversely, ‘private’ means something closed and exclusive.23

Despite the absence of expression at the institutional level, the growing demand to eradicate the visibility of Islam, in Europe or elsewhere, not exempted from sometimes revolutionary political influences cannot go unnoticed

European modernity, as asserted in the 20th century, is described essentially as a product of the separation between church and state: European countries built their idea of modernity by relegating religion and the sacred to the private sphere. The exclusion of religion, as a cornerstone of public relations, has ensured the rights of individuals, including women. According to this interpretation of modern Europe, Muslims represent a potential danger through their publicly displayed religious practices, such as the wearing of the veil for women, and invade public space, the dominant territory of the secular state. Despite the absence of expression at the institutional level, the growing demand to eradicate the visibility of Islam, in Europe or elsewhere, not exempted from sometimes revolutionary political influences cannot go unnoticed.24

Scott has shown that, with regard to France, the introduction of a gender perspective in the analysis of discourse on the headscarf makes it possible to indicate the way in which colonial representations of difference are still at work in public policy.25 It is a question, according to Scott, of articulating conquest, colonization, and struggles for independence with the most current forms of discrimination and inequality to show that the Islamic headscarf has always been a political emblem and that it continues to represent the conflict between France and its own colonial past, embodied today by diversity. According to Françoise Verges,26 there is Franco-centered feminism that is itself imbued with certain colonialism. This feminism reenacts the ‘civilizing mission’ of colonization by seeking to impose a Western lifestyle on all women and refusing to address the senselessness of race.

This testimony refers to the idea that feminism too can ‘imbibe’ ethnocentric and racist conceptions as soon as it locks itself in a model of liberation that it ‘imposes’ on all women, without taking into account their specific positions in social relationships (being black or white in a Western country differentiates the type of oppression experienced). According to Fabienne Brion, the “question of women in Islam,” as expressed in positions taken on wearing the headscarf, serves above all to legitimize the domination of Westerners over Muslim populations.27 The perception that makes Muslims ‘barbarians’ who mistreat their wives becomes a process of affirming the superiority of European culture.

But the introduction of a gender perspective in the cross-analysis of the debates on the headscarf in France also allows us to question the specific modes of contemporary ‘racialization’ of European citizens, residents, and migrants –believers or not, practicing or not– as well as the modalities of legitimation of the headscarf.28 Indeed, rather than questioning the aftermath of colonialism and decolonization or the historical continuity of colonial stereotypes, discourse on the headscarf questions the modes of hierarchical differentiation of individuals, bodies, and sexualities –modes that colonialgaze, as a look at the other, is capable (or not) of reactivating or exacerbating in a postcolonial context. Adopting a gender perspective, then, makes it possible to deconstruct the presuppositions of discourse on gender equality in French controversies. The presumption that the autonomy and emancipation of women is a fait accompli in Western societies and the headscarf would harm them are some examples. The fallout from such a systematic association between Western modernity and equality on the implementation of integration (or even assimilation) policies is supplanting equality policies.29

In France, public and political debates on Islamic scarves and veiled Muslim women formulate the diversity between Islam and Christianity in terms of a hierarchical dichotomy. On the one hand, the ‘uncivil’ practice of a backward ‘religious formation rooted in an essentially patriarchal and unequal and therefore inferior tradition’ (Islam); on the other, a ‘superior’ culture, synonymous with both ‘civilization’ and ‘modernity’ (Christianity). On the one hand, Islam, which veils ‘its’ wives; on the other, the emancipation of women and gender equality as ‘fulfilled’ realities in Western Jewish and Christian modernity. Gender equality presents itself as the cornerstone and the building block of this dichotomy. While the rhetoric of ‘the emancipation of women’ has contributed in the past to legitimizing conquest and colonialism;30 it is today redeployed within the framework of a neocolonial discourse according to which gender domination is the exclusivity of minority religions and ‘cultures’ defined as pre-or anti-modern, thus concealing the inequalities of sex, gender, and sexuality that persist in European societies.31

Muslim Visibility: Threat to French Laïcité?

In the construction of the veil as a major political and social problem, as a ‘threat to laïcité’ or to the French way of life according to its detractors, the veil itself ends up becoming a floating signifier that can take other forms, like that of the bandana, the long skirt, the over-covering swimsuit, etc. However, the different cases of the veil are part of a longer period that does not begin in 1989, but during the colonial period when France claimed to be a Muslim power and a place where a fringe of French Algeria invested the French women of generals of the secret armed organization, Organisation Armée Secrète (OAS) on the task of ‘freeing’ Algerian women from their veil; it is also a question of showing how the rewriting of the history of French laïcité in a discourse of gender equality has contributed to nationalization of feminism, otherwise known as fémonationalisme.32 In the French context, there are at least two historical moments in which Muslim veils were major centers of interest: the colonial project to unveil Algerian women and the contemporary debate around young Muslim girls wearing the veil in schools. The crucial question then remains: “What has the veil come to mean in the contemporary French context so that there is recourse to a law aimed at excluding it from public schools?”33

In France, public and political debates on Islamic scarves and veiled Muslim women formulate the diversity between Islam and Christianity in terms of a hierarchical dichotomy

In France, feminists in favor of the 2004 law prohibiting the headscarf in schools justify their position at times in the name of the principle of laïcité (i.e., wearing the headscarf constitutes an attack on laïcité) and sometimes in the name of the principle of gender equality. These arguments are explicit in a petition addressed to then-President Jacques Chirac and published by Elle magazine, in which they asked for a law that not only reaffirms the principle of laïcité by prohibiting visible religious signs in the public sphere and clearly giving those responsible for these public services the legal means to enforce the principle of gender equality. These arguments also remind readers that the Islamic veil refers to discrimination against women. It is thus specified that it can be a question of prohibiting the headscarf in the street, if necessary, given that France is a nation that respects two principles: laïcité and the equality of the sexes.34

Thus, from its origin as a ‘school question,’ laïcité transformed into a ‘global question’ on republican cohesion and the future of ‘French’ citizenship. But this change was not carried out without ambiguity.35 As aptly put by Balibar36 “the school space provided the privileged place for the implementation of the utopias of citizenship.” In fact, the school engaged little in the rhetoric of gender equality, but rather that of citizen equality, until 2003. As such, we can say that 2003 marks a turning point in the discourse of the scandal speech: gender equality comes into play in a way that certainly had been prepared for in 1989 by the participation of two ‘historic’ feminists in the drafting of “the Munich” of the Republic,37 but which was not yet formulated clearly as a national standard. From the law of 2004, it will no longer be only the veil that is the subject of meticulous regulation, but anything that can be a substitute symbolically, like bandanas, whose length will be measured in establishments; skirts, of which we will also measure the size; and pants in sports competitions such as beach volleyball.

School is the hotspot of laïcité. It is where laïcité remained in conflict at a time when the laïcité of the state and the nation seemed to be appeased and reconciled

In addition, the marketing of burkinis and hijabs by major universal brands such as D&G or H&M is qualified as irresponsible by Minister for Women’s Rights Laurence Rossignol. For her, there is no doubt that these brands are about “the promotion of the confinement of the body of women.” Referring to the concept of ‘voluntary servitude’ to support her words, she stated: “There are women who choose, there were also American Negroes who were for slavery.” This position is shared by the feminist philosopher Elisabeth Badinter, who believes that one cannot wear the veil and defend equality between women and men.38

Feminism, Emancipation, and Discriminations

The Veil

Religion is often characterized by the French left as being in itself alienating (‘the opium of the people’), the liberation of people under its ‘grip’ becoming an essential element of any progressive project of emancipation.39 The case of Islam is a barometer of the changes that have recently taken place in the West, as regards a certain ‘deprivatization’ of religion. In France and Belgium, there is a desire for political control of Muslim associations and mosques on their territory. In the case of French laïcité, a delicate history of managing the threshold of the ‘visibility’ of religion has marked this model until today, against a background of mistrust with a view to safeguarding ‘public peace.’40 The news still risks reducing laïcité to a specific subject, such as ‘visible’ religious symbols, more specifically the ‘scarf.’ But laïcité was reduced to a completely different problem two decades ago: that of public subsidies to private educational establishments under contract.

School is the hotspot of laïcité. It is where laïcité remained in conflict at a time when the laïcité of the state and the nation seemed to be appeased and reconciled. The conflict over secular education, continuing to bring former Catholic and secular adversaries into confrontation, continued until recently, since the last major demonstration on public school, concerning the Falloux law, dates from 1994. However, the conflict over secular school and private school, which lasted many decades, seems to have been forgotten very quickly, as if there had been consensual laïcité41 before Islam.

Discussions around scarf in France is the result of media and political construction which began a few months earlier, notably through the publication in Le Quotidien de Paris, on June 13, 1989, of an article by Ghislaine Ottenheimer describing the problems posed by the wearing of headscarves by young students from Épinal in their school, which was not something novel. As Jean Baubérot points out, a presentation brochure from the Gabriel-Havez college in Creil, published a few months earlier, showed a photograph of several students wearing the veil. Two of the three girls (who would be excluded under the current law) had worn a scarf since their entry into college, without this having posed any major problem up to that point.

Protest against the proposed ‘Anti-Separatism’ bill, still to be approved by France’s National Assembly, following an amendment that would ban the wearing of Muslim headscarves for those under the age of 18. in Paris, France on April 9, 2021. SAM TARLING / Getty Images

Protest against the proposed ‘Anti-Separatism’ bill, still to be approved by France’s National Assembly, following an amendment that would ban the wearing of Muslim headscarves for those under the age of 18. in Paris, France on April 9, 2021. SAM TARLING / Getty Images

In other establishments in the Creil basin, similar situations would not give rise to such media coverage. The explosion of the case was undoubtedly linked to the will of the principal, Ernest Chénière, whose political commitments were to the right of the right, and who transformed his position into an electoral argument in the short political career he soon began. Furthermore, the interest of the French media appeared from the start of the school year. On October 3, an article appeared in the regional daily newspaper, Le Courrier Picard. The controversy swelled quickly: The next day, October 4, it was on Liberation’s headlines: “Wearing the Veil Strikes laïcité at the Middle School of Creil.” A report in which Ernest Chénière and the father of the young girls speak was broadcast on the main public TV station. The entire national press took it in stride. The settlement of the situation of the Creil schoolgirls did not definitively resolve the question of the scarf –far from it. From 1990 until the law of February 2004, similar cases would appear, causing more or less debate and reaction.42

From the very first ‘veil affair’ of 1989 to this day, debates on the law regarding religious signs at school and the Islamic veil, in particular, have occupied a large place in the French political media space. A real digest of political meanings and facilitator of controversies43 reveals the internal tensions in feminisms that are reluctant or opposed to the integration in their discourses and practices. This reflects the close relationship between colonial history, on the one hand, and the struggles and definitions of feminism, on the other. The veil was in fact constructed as an anomaly within the Republic, a religious sign that would widely offend the common sense of gender equality and laïcité as a constitutive value of the West.44

As expressed in the Stasi report, problems arose with real acuteness on the school grounds. In a partially closed environment, the students must learn and live together in a situation where they are still fragile, subject to external influences and pressures. The functioning of the school should enable them to acquire the intellectual tools intended to ensure their critical independence in the long term. Therefore, reserving a place for the expression of spiritual and religious convictions was not obvious. The report also recalled that within the school grounds, with the exception of private educational establishments, the reconciliation between freedom of conscience and the requirements of the neutrality of the public service was delicate. The veil affair, together with all of its media dimensions, was the symbol of this development. When the question surfaced for the first time in 1989, the political authorities, faced with an outburst of passions, preferred to seize the Council of State. The government had only asked the State Council to rule on the rule of law at a given time. In addition, the context was significantly different from what we know today. The evolution of the terms of the debate over several years makes it possible to measure the rise in power of the problem.45 The ban on headscarves in schools was enacted in 2004, on the grounds that religious symbols are against laïcité.

The ban on headscarves in schools was enacted in 2004, on the grounds that religious symbols are against laïcité

Since 2004, this debate has crystallized around the veil and the Muslim religion, which have become the new symbols of patriarchal oppression and the clerical threat in the public space (in politics and the media). Presented as inherently demeaning, the veil was first used by the self-proclaimed defenders of laïcité to form a ‘republican’ camp claiming to oppose the grip of ‘religions’ on the public sphere, but generally focusing on Islam. Dividing the feminist movement, the veil revealed the complexity of the religious question in a supposedly ‘neutral’ public space. Nested in relationships of gender, race, and class, religion cannot be understood as a one-dimensional phenomenon. Laïcité presented itself as being more effective in a society where punishment, prohibition, and exclusion are inseparable from a humanist policy aiming to ‘save’ veiled women. In other words, it is in the name of feminism that veiled women are punished for this paradox that emancipation goes through an ‘unveiling.’ The veil is also associated with signs of exogenous male domination, reduced to the cultural specificity of Islam, only to the false conscience of these women who would be wrong in finding their salvation in religion rather than in allegiance to the dress codes of republican neutrality. As a result, the reason why feminists have taken up the issue (namely women’s clothing and the idea of supposed restraint in this area and a patriarchal disciplinary device) is also the reason why we are going to exclude young girls from school: namely the emancipation of women.46

The arguments of politicians on the need for such a measure are based on the theses advanced by some feminists who see in the veil not only the oppression of women but also as a symbol of the impossibility of fighting for women’s rights.47 In fact, feminists are divided into three main groups on this discussion: While some of them endorse the law, some other feminists who are numerically weaker are against it. The third group, who compromise the majority of feminists, remain undecided. Those opposing the law believe that the Muslim population in France has already been stigmatized and discriminated against by indirect means (e.g., the non-engagement of a person whose name is Arabic-sounding), their rights attached to French nationality are refused and they are otherized due to ‘their cultural difference.’ They also stipulate that the law is racist and, as such, reinforces the stigmatization of Muslims; they add that it actually sanctions girls and not their fathers or brothers who would force them to wear the headscarf. Above all, they protest against laws that attack the body, the mind, and the soul of women.

Tensions centered around the scarf affair in France have largely crossed national borders for the last 20 years. The French conflict seems to serve as a backdrop for feminists from other countries to analyze their own practices toward Muslim migrants and immigrants.48 The 2004 law was conceived as a ‘feminist’ or anti-sexist law –as the means by which France could combat the oppression of women in one of its last entrenchments– in its Muslim communities and in its suburbs (despite the absence of any reference to gender or gender equality in the text of the law). Relying on the construction of a link between Islam and gender oppression, arguments in favor of the law may have blurred the distinction between French-style laïcité (and French national identity in which laïcité is supposed to occupy a central place) and gender equality. Through opposition to the oppression of women in the guise of the Islamic veil, French society ostensibly reiterates its commitment to gender equality (which some commentators take for granted).49

It is as if differences between ‘them,’ i.e., veiled Muslims, and ‘us’ is an obstacle to the progress of ‘Western civilization’ rather than a modality of the functioning of modern power. Inequality, heteronomy, and sexual violence are apprehended in debates on the wearing of the headscarf as symptoms of an incomplete modernization, as elements linked to underdevelopment, to backward or residual attitudes and mentalities with cultural resistances to modernity –rather than as systematic power relations constituting modernity. However, the analysis of the terms in which the dichotomy between Islam and Christianity is formulated in the debates on the headscarf reveals the lasting power not only of the social and political but also the epistemic effects of the historical construction of difference over contemporary discussions around “identity, culture and national and European values.”50 Scott51 emphasizes gender equality as the founding principle of the French Republic and the British Monarchy as a way of illuminating the colonial paradigm of the ‘clash of civilizations:’ those who do not share this principle are not only different, they are inferior as well. The inassimilable quality of being Muslim therefore goes hand in hand with its incompatibility with the principle of gender equality.

Even in cases where the young women insist on the personal nature of the choice to wear the veil, their acts are attributed to bad faith, which does not allow the existence of authentic freedom

Implicitly, the position in favor of the veil law supposes that veiled women cannot have their freedom of conscience, since their autonomy as agents and their subjectivity are mutilated by forms of religious or community oppression; they are ‘de-subjectified.’ Even in cases where the young women insist on the personal nature of the choice to wear the veil, their acts are attributed to bad faith, which does not allow the existence of authentic freedom.52 In this context, parents are also accused of forcing students to veil. But the question about the headscarf issue in school is not that children are influenced by their parents’ choices. Indeed, all children may be influenced by their parents’ choices, as they are influenced by their classmates, teachers, and, most of all, the internet. The question here, rather, is why this influence of parents and living environments is declared problematic only when the discussion has to do with the Muslim headscarf?53 So, the ‘French laïcité’ elaborated in this research poses a major problem. By considering religion as automatically alienating and its believers, especially female believers, as oppressed people who should be ‘saved,’ laïcité appears in the eyes of many as an instrument of discrimination against a specific religion rather than as a principle of state neutrality.54

The Burqa

Women of Muslim faith in burqas or niqabs constitute a minority within Islam. However, it arouses excitement in Western societies to circulate in a public space with a covered face. French and Belgian legislators intervened by adopting a general prohibition rule, despite the reluctance of the bodies consulted on the question as to the legal conformity of such a measure with regard to international law and constitutional law. Thus, French Law no. 2010-1192 of October 11, 2010, prohibiting the concealment of the face in public space and the Belgian law of June 1, 2011, aiming to prohibit the wearing of any clothing totally or mainly hiding the face, introduced a new criminal law provision into these countries’ respective legal systems.55

The question of integration, naturalization, and citizenship is strongly linked to cultural assimilation, meaning assimilation into the national culture. The decision of the Council of State of June 27, 2008 approved the refusal to grant French citizenship to a fully veiled (niqab, burqa) Moroccan national is a case in point. The argument advanced was that of the ‘non-assimilation’ of the person in question due to a radical practice of his own religion incompatible with the essential values of the French community, in particular, with the principle of gender equality.56

Face veiling has become a hot topic and has been covered widely by the media. It has prompted every citizen to speak out with or without any knowledge of the terrain, a situation reminiscent of the controversy over the veil at school a decade earlier, which was to lead to the veil ban in 2004.”57 In France and more generally in Europe, the burqa represents a manifestation of so-called ‘radical Islam,’ which is perceived as one of the primary threats to Western society. It generally refers, in the Western collective imagination, to both terrorism and the mistreatment that Islam supposedly reserves for women. Its appearance in Europe has provoked hostile reactions pointing to the full veil as proof of the impossibility of integrating immigrants of Muslim origin and, more generally, of the incompatibility of Islam with the Republic and the values of democracy. In France, the garment was the subject of a controversy launched in June 2009 by Nicolas Sarkozy declaring that the burqa is not welcome on French territory.58

France also triggers debates about the veil and burqa in other European countries and encourages them to deal with veil issues of Muslim women within the paradigm of cultural racism

According to Emanuel Levinas, there is a lack of citizenship for those who hide their faces from others. He speaks of the woman in a burqa as a descendant of immigrants, having not completed her integration process yet, thus bringing up the question of living together. He states that there are limits to this recognition of particularisms, even in the private sector. He focuses on traditional cultures in which there is statutory inequality or rather assumed inferiority of women. In this context, the burqa is mentioned right after female circumcision as a practice deemed to be contrary to individual freedom and citizenship values.59

In addition to the external threat associated with ‘Islamic terrorism,’ then, the burqa poses an internal threat that would tend to flout the fundamental principles that form the basis of liberal democracies. The full veil, thus, refers to a form of religiosity conveying values incompatible with these liberal values, or even ‘hostile’ to the ‘essential values’ of society, both terms used by the French Council of State in its decision of June 27, 2008. Signifying a negation of democratic principles and undermining the principle of laïcité, the full veil would thus reflect a rise in communitarianism and a refusal to integrate into the political community. The social construction of ‘the burqa problem,’ both by the media and by political actors, legitimized the entry of this question into the political field. Thus, a practice that only corresponds to an epiphenomenon of the transformations of contemporary religious practices found itself apprehended by the nation as a foreign body, against which it was necessary to fight. The full veil as a cultural object refers to the question of the integration of populations from immigrant backgrounds. When the burqa is considered to be the bearer of values incompatible with the essential values of a democratic society, its wearing is interpreted as a rejection of the principles that lie at the foundation of the political community.60

The controversy over the burqa continues to this day. As had been the case earlier for their veiled co-religionists at schools, women in the niqab started to be dispossessed of their subjectivity in French public discourse. They have rarely been presented as autonomous subjects, but rather as women incapable of constituting themselves as subjects in their social relationships. Their social reality has been largely concealed; they are the subject of caricature projections that are strongly anchored in French public opinion.61 For supporters of the laws prohibiting the veil and burqa in 2004 and 2010, ‘liberating women,’ was a recurring theme during the debates in the Assembly that preceded the passing of these two laws.

Another imagined grip that supporters of the law seek to break is that of a fanatic imam who would manipulate Muslim women. The burqa is cited as the exacerbated manifestation of Muslim communitarianism, posing a threat to ‘national identity.’62 The burqa, thus, joins the other visible symbols of Muslim religiosity in the public space that create controversy, such as mosques, minarets, the veil, halal rays in supermarkets or Islamic banks, all figures of rejection associated with an imaginary invasion. Immigrants are the subject of several fantastical representations of which the demographer Hervé Le Bras63 sets out the characteristics: this fear of foreign invasion is intimately linked to the colonial adventure, the factors of which it reverses, with “a transformation of emigration into colonization and the perception of immigration as an invasion.” Because of their visibility in the common public space, women in burqas are pointed out as bad citizens, refusing republican values.64 Tévenian emphasizes that:

it is neither voluntary servitude, nor alienation, nor confinement, nor physical inconvenience, nor self-shame, nor masking of the face, nor the concealment of the hair that poses a problem –since all this is perfectly tolerated, even encouraged, when one stays in a white and Western frame. What is problematic is precisely the non-white and non-Western character of the veil (hijab) or niqab.65

Conclusion

Questions about the dress of Muslim women in the French public space continue to depict the controversy as an opposition between those who act for freedom of religion and those who demand a neutral space. The place of religion in the public sphere is debated in the name of French republican principles. Thus, the concept of laïcité continues to remain at the epicenter of those debates and controversies examined in detail in this study. Although it designates the separation of religion and state and the neutrality of the latter, the concept of laïcité remains very confused both in description and application.

In the French case, there is a liberal laïcité in which religion is not a problem, since it is a question of neutrality not for individuals but for institutions. As for republican laïcité, freedom of religion and conscience in the public sphere remains a subject of discussion. The distinction between public and private domains is also defended by feminist thinking, which makes laïcité a weapon for the emancipation of women. Indeed, as this research argues, the visibility of Muslim women is contested in the name of laïcité by some feminists who prioritize ‘Western and white’ by ignoring the rights of all other women. Additionally, the discourse of France’s colonial past is also present in the attitudes of feminists toward women of Islamic affiliation. In this regard, the headscarf or any other piece of clothing of a Muslim character is seen to be problematic. In line with the civilizing and racist missions of the past colonial thought, some feminists who exclude not only Muslims but also black, African, or other minority groups still work not for diversity, but for a unity imposed by an ethnocentric ideology. As a result, emancipation based on Western lifestyles becomes the watchword of a feminist discourse where the headscarf finds no place. Having shed light on the French case, this study also emphasizes that the position of certain feminists with regard to the headscarf became clearer with the appearance of the ban on the headscarf in certain schools at the end of the 1990s and particularly with the introduction of the law in 2004. The discriminatory approach of hierarchical differentiation, minoritization, marginalization, and disapprobation of some Western feminists toward the Islamic veil is also found in the attitude toward the burqa and the niqab. Both are banished from the public sphere for the same reasons.

To conclude, the visibility of Muslim women in the French case is seen as a threat to democracy, integration, citizenship, and emancipation. In fact, Muslim women are discriminated against in the name of laïcité and freedoms. Feminist positions that use laïcité as an argument run the risk of developing an ethnocentric vision of sexism and the emancipation of women. Within a wider framework, it can be argued that the French case is presented as an example to other countries, especially European ones and Belgium in particular, for protecting the rights of Muslim women. Nevertheless, it actually is the opposite. Under the name of ‘emancipation,’ France discriminates against Muslim women rather than integrating them into the French public sphere. By doing so, France also triggers debates about the veil and burqa in other European countries and encourages them to deal with veil issues of Muslim women within the paradigm of cultural racism.

Endnotes

1. Andrew Heywood, Siyasi İdeolojiler, translated by Levent Köker, (Ankara: 2013), p. 235.

2. Kristin Aune, Mia Lövheim, Alberta Giorgi, Teresa Toldy, and Terhi Utriainen, “Introduction: Is Secularism Bad for Women?” Social Compass, Vol. 64, No. 4 (2017), pp. 2-4.

3. Chantal Jouanno, “Rapport d’Information,” SÉNAT, Session Ordinaire de 2016-2017, 101 (November 3, 2016), retrieved January 5, 2021, from https://www.senat.fr/rap/r16-101/r16-1011.pdf; Hourya Bentouhami, “Les Féminismes, le Voile et la Laïcité à la Française,” Socio, Vol. 11, (2018), p. 119.

4. Pragna Patel, “Multi-Faithism and the Gender Question: Implications of Government Policy on the Struggle for Equality and Rights for Minority Women in the UK,” in Liz Kelly, Yasmin Rehman, Hannana Siddiqui (eds.), Moving in the Shadows: Violence in the Lives of Minority Women and Children, (London: Routledge, 2013), pp. 41-58.

5. Élisabeth Badinter, Fausse Route, (Paris: Odile Jacop, 2003).

6. Rashmi Varma, Sukhwant Dhaliwal, and Chitra Nagarajan, “Why Feminist Dissent?” Feminist Dissident, İnaugural Issue, Vol. 1 (2016), pp. 1-32.

7. Reilly and Toldy quoted in Kristine Aune et al., “Is Secularism Bad for Women: La Laïcité Nuit-Elle aux Femmes?” Social Compass, Vol. 64, No. 4 (2017) pp. 3-4.

8. Nacira Guénif-Souilamas, “La Fin de l’Intégration, la Preuve par les Femmes,” Mouvements, 3, No. 39-40 (2005), pp. 152-153.

9. The official website of Marianne, retrieved May 8, 2021, from https://www.marianne.net/magazine/10-mai-1981-10-mai-2021-40-ans-les-40-trahisons-de-la-gauche.

10. Maria Eleonora Sanna, “Ces Corps qui ne Comptent pas: Les Musulmanes Voilées en France et au Royaume-Uni,” Cahiers du Genre, Vol. 50, No. 1 (November 2011), pp. 117-118.

11. Léonard Faytre, “Islamophobia in France: National Report 2019,” in Enes Bayraklı and Farid Hafez (eds.), European Islamophobia Report 2019, (İstanbul: SETA, 2020), p. 293.

12. Myriam Hunter-Henin, “Religion, Children and Employment: The Baby Loup Case,” International and Comparative Law Quarterly, 64, No. 3 (July 2015), pp. 717-731.

13. Bentouhami, “Les Féminismes, le Voile et la Laïcité à la Française,” p. 119.

14. Bentouhami, “Les Féminismes, le Voile et la Laïcité à la Française,” p. 120.

15. Marc Jacquemain, La Laicité et les Libertés, (Belgique: ULg, 2016), pp. 1-2.

16. Alexandre Piraux, “Extraits du Rapport de la Commission STASI sur la Laïcité,” Pyramides, 8, (2004), pp. 107-136.

17. Maurice Barbier, “Pour une Définition de la Laïcité Française,” Le Débat, 134, No. 2 (2005), pp. 129-141.

18. Niraja Gopal Jayal, “Religion, Secularism and the State,” Global Center for Pluralism, (April 2017), retrieved December 22, 2020, from https://www.pluralism.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/NirajaJayal_Secularism_EN.pdf, p. 2.

19. Jacquemain, “La Laicité et les Libertés,” pp. 5-6.

20. Jacquemain, “La Laicité et les Libertés,” pp. 6-7.

21. Louisa Acciari, “Féminisme et Religion, Entre Conflits et Convergences. Le Cas des Femmes Syndicalistes au Brésil,” Contretemps, (October 16, 2012), retrieved January 11, 2021, from http://www.contretemps.eu/feminisme-et-religion-entre-conflits-et-convergences-le-cas-des-femmes-syndicalistes-au-bresil/.

22. Ronnie Cohen and Shannon K. O’Byrne, “‘Can You Hear Me Now… Good!’ Feminism(s), the Public/Private Divide, and Citizens United,” UCLA Women’s Law Journal, 20, No. 1 (November 2012), p. 39.

23. Cohen and O’Byrne, “‘Can You Hear me Now... Good!’” p. 43.

24. Diana Tasini, “Le Voile des Femmes Arabes, Point de Division Entre Espace Public et Religiosité,” Philonsorbonne, Vol. 8, (2014), pp. 189-190.

25. Scott quoted in Sanna, “Ces Corps qui ne Comptent pas,” p. 114.

26. Vergès quoted in Séverine Kodjo-Grandvaux, “Françoise Vergès: “Les Droits des Femmes sont Devenus une Arme Idéologique Néolibérale,”” Le Monde, (February 17, 2019), retrieved December 10, 2020, from https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2019/02/17/francoise-verges-les-droits-des-femmes-sont-devenus-une-arme-ideologique-neoliberale_5424588_3212.html.

27. Brion quoted in Patricia Roux, Lavinia Gianettoni, and Céline Perrin, “Féminisme et Racisme: Une Recherche Exploratoire sur les Fondements des Divergences Relatives au Port du Foulard,” Nouvelles Questions Féministes, 25, No.1 (2006), p. 91.

28. Étienne Balibar, “Le Retour de la Race,” Mouvements, 50, No. 2 (2007), pp. 162-171.

29. Sanna, “Ces Corps qui ne Comptent pas,” pp. 114-115.

30. Eleni Varikas, Les Rebuts du Monde: Figures du Paria (Paris: Stock, 2007), p. 112.

31. Sanna, “Ces Corps qui ne Comptent pas,” pp. 113-114.

32. Bentouhami, “Les Féminismes, le Voile et la Laïcité à la Française,” pp. 118-119.

33. Alia al-Saji, “Voiles Racialisés: La Femme Musulmane dans les Imaginaires Occidentaux,” Les Ateliers de l’Éthique, 3, No. 2 (September 2008), p. 41.

34. Roux et al., “Féminisme et Racisme,” p. 88.

35. Jean Baubérot, “La Laicité en Question,” IFRI, (December 2004), retrieved February 2, 2021, from https://www.ifri.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/pp12bauberot.pdf, pp. 2-4.

36. Balibar quoted in Bentouhami, “Les Féminismes, le Voile et la Laïcité à la Française,” p. 119.

37. Joan Wallach Scott, “The Veil and the Political Unconscious of French Republicanism” The Institute Letter (Summer 2016), retrieved May 26, 2021, from https://www.ias.edu/ideas/2016/scott-veil-in-france.

38. Carole Boinet, “Pourquoi la Question du Voile Divise-t-elle les Féministes?” Lesinrocks, (April 8, 2016), retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://www.lesinrocks.com/2016/04/08/actualite/actualite/question-voile-divise-t-feministes/.

39. Acciari, “Féminisme et Religion, Entre Conflits et Convergences.”

40. Solange Lefebvre, “Les Religions, Entre la Sécularité et la Participation à la Sphère Publique,” in Solange Lefebvre (ed.), La Religion dans la Sphère Publique, (Montreal: University of Montreal Press, 2005), pp. 378-380.

41. Jean Baubérot, “La Liaicté en Question?” pp. 1-16.

42. Hervé Le Fiblec, “La Laïcité: Un Principe Progressiste?” IRHSES, 38 (February 2017), pp. 5-6, retrieved January 25, 2021, from http://www.irhses.snes.edu/PDR-no-38-La-Laicite-un-principe-progressiste.html, pp. 5-6.

43. Nilüfer Göle, Musulmans au Quotidien, (Paris: La Decouverte, 2015), pp. 155-156.

44. Bentouhami, “Les Féminismes, le Voile et la Laïcité à la Française,” p. 117.

45. Piraux, “Extraits du Rapport de la Commission STASI sur la Laïcité,” pp. 107-136.

46. Bentouhami, “Les Féminismes, le Voile et la Laïcité à la Française,” pp. 119-120.

47. Christine Delphy, “Antisexisme ou Antiracisme? Un Faux Dilemme,” Nouvelles Questions Féministes, 25, No. 1 (2006), pp. 60-65.

48. Roux et al., “Féminisme et Racisme,” pp. 84-86.

49. Al-Saji, “Voiles Racialisés,” p. 42.

50. Joyce Marie Mushaben, “More than Just a Bad Hair Day: The Muslim Head-Scarf Debate as a Challenge to European Identities,” in Holger Henke (ed.), Crossing Over: Comparing Recent Migration in the United States and Europe, (New York: Lexington Books, 2005), p. 185.

51. Scott quoted in Sanna, “Ces Corps qui ne Comptent pas,” p. 114.

52. Al-Saji, “Voiles Racialisés,” p. 42.

53. Jacquemain, “La Laicité et les Libertés,” p. 11.

54. Acciari, “Féminisme et Religion.”

55. Sofia Vandenbosch, Cachez ce Voile que Je ne Saurais Voir: Les Lois Anti-burqa: De l’arrêt de la Cour Constitutionnelle à l’arrêt de la Cour Européenne des Droits de l’Homme, (Belgique: Ulg, 2016), retrieved December 17, 2020, from https://orbi.uliege.be/bitstream/2268/200481/1/Cachez%20ce%20voile%20que%20je%20ne%20saurais%20voir.pdf, pp. 1-2. It may be interesting to revisit these laws in the context of the pandemic COVID-19 once the latter will be over.

56. Sanna, “Ces Corps qui ne Comptent pas,” pp. 123-124.

57. Camila Arêas, “Les Nominations de ‘l’Affaire du Foulard’ dans la Littérature en Sciences Humaines et Sociales: Enjeux Socio-politiques de l’Argumentation Scientifique,” Argumentation et Analyse du Discours (2016), retrieved January 19, 2021, from https://journals.openedition.org/aad/2240.

58. For an overview of the arguments against the full veil in the controversy that started in 2009, see, Dominique Schnapper, “Le Port du Voile Intégral en France: Une Épreuve pour l’Ordre Démocratique,” in David Koussens and Olivier Roy (eds.), Quand la Burqa Passe à l’Ouest: Enjeux Éthiques, Politiques et Juridiques, (Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2013), pp. 79-87.

59. Agnès De Féo, “Les Femmes en Niqab en France,” Socio, Vol. 11, (2018), pp. 141-142.

60. David Koussens and Olivier Roy, “Introduction Pour en Finir Avec la ‘Burqa?’” in David Koussens and Olivier Roy (eds.), Quand la Burqa Passe à l’Ouest, (Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2014), pp. 8-9.

61. Raphaël Liogier, Le Mythe de l’Islamisation. Essai sur une Obsession Collective, (Paris, Seuil: Points Essais, 2012), pp. 35-55.

62. Fabrice Dhume, Communautarisme: Enquête sur une Chimère du Nationalisme Français, (Paris: Demopolis, 2016), pp. 50-52.

63. Hervé Le Bras, “L’Invention de l’Immigré,” (La Tour d’Algues: l’Aube, 2012), pp. 13, 17.

64. De Féo, “Les Femmes en Niqab en France,” 143-144.

65. Pierre Tévanian, Dévoilements: Du Hijab à la Burqa, (Paris: Libertalia, 2012).