NATO’s military strikes on Libya, under UN Security Council Resolution 1973, to dislodge the Gaddafi regime is widely viewed as the “watershed moment” in the short history of the “responsibility to protect” doctrine, commonly referred to as R2P. Ardent supporters of this doctrine claim that the use of military force against Gaddafi to save Libyan lives was in line with the original spirit of R2P; the doctrine, they further claim, came of age with the defeat of Gaddafi forces through NATO’s bombings. However, despite what the supporters argue, NATO’s intervention in Libya has seriously undercut the R2P doctrine itself.

A critical look at how R2P was applied to Libya points to a political episode full of contradictions, giving rise to serious questions as to whether the use of force was consistent with the original R2P report, developed by the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS) in 2001, and whether the appropriate stipulations in related relevant documents, such as the 2005 UN World Summit Outcome Document and the 2009 report of the UN secretary-general, Implementing the Responsibility to Protect, were observed. A more serious question is whether NATO succeeded in protecting the civilian population or if it killed more Libyans by bombing civilian sites and cities held by Gaddafi forces.

If R2P had come of age in Libya, it has certainly seen a tragic death with the Security Council’s inability to initiate actions on Syria

After Libya R2P has stalled; it has not been used in Syria or Yemen where more egregious crimes against humanity were and are being committed. If R2P had come of age in Libya, it has certainly seen a tragic death with the Security Council’s inability to initiate actions on Syria. The Council’s inaction has come as no surprise and was not a shocking development. As a liberal humanitarian doctrine, R2P mixes up humanitarian causes with realpolitik on the global stage, promotes Western warmongering under a humanitarian umbrella, and ends up committing the very crimes against humanity that the doctrine purports to stop. This commentary examines the R2P-inspired military intervention in Libya, and specifically argues that the death of the R2P doctrine in Syria was made inevitable by Western abuses in Libya, and that the doctrine is doomed to a bleak future.

Responsibility to Protect: The Doctrine

The R2P doctrine is premised on the idea that sovereign states not only have the primary responsibility to protect their peoples, they also have a collective extra-territorial responsibility to protect populations from mass atrocities everywhere. If a particular state is unable or unwilling to stop or avert large-scale human sufferings resulting from internal armed conflicts or government repressions that state loses its sovereign immunity to external interference in order to protect its people. The ICISS report suggests three main types of responsibilities to protect: prevention, reaction, and rebuilding after intervention. It emphasizes prevention—that is addressing the root causes of internal strife that puts humans at risk—as “the single most important dimension” of R2P.

The controversial part of the ICISS report is its elaborate discussions on where and how military interventions to protect humans may be warranted and executed. It sees military intervention as a last resort in cases where large-scale loss of life and “ethnic cleansing” are threatened or actually occurring (Article 4.19 of the ICISS report). External intervention to avert such grave situations can be undertaken only after all diplomatic and non-military avenues to peacefully resolving the humanitarian crisis have been exhausted (Article 4.37). Article 6.14 places the burden of responsibility for R2P military intervention issues with the UN Security Council, while at the same time recognizing the Council’s democratic deficiencies and “institutional double standards”. The ICISS report thus hinges more on peaceful strategies to resolve impending humanitarian crises than supporting foreign armed interventions to fix foreign problems.

Clearly then, the theoretical significance of the R2P doctrine lies in initiating a paradigm shift from the hotly debated right of intervention, promoted in the 1990s by the concept and practices of humanitarian intervention in such places as Kosovo in 1999, to an obligation to intervene. Article 2.4 of the ICISS report says: “We prefer to talk not of a ’right to intervene’ but of a ‘responsibility to protect’”. The report also re-conceptualizes sovereignty by reframing the traditional concept of state sovereignty to the idea of individual sovereignty. A state is thus seen as nothing but a collective political unit created and owned by its citizens. The debate then shifts from state sovereignty, as guaranteed by the UN Charter principle of non-intervention in the domestic affairs of member states (Article 2.7) to how to protect the individuals in states from atrocities and promote individual sovereignty. If state sovereignty is misused to justify atrocities against citizens, the international community can therefore invoke individual sovereignty to protect citizens from large-scale killings, tortures and repressions.

The ICISS report, however, fails to uphold its universal humanitarian mission, principles, and procedures. In terms of the application of R2P, it discriminates between rich and poor, weak and powerful states. Article 4.42 of the report excludes the five permanent members and other great powers where the obligation to intervene would not apply even if all the conditions for intervention were satisfactorily met. The great powers are free to treat their citizens in any way they like but not the weaker powers who must comply with the R2P norm to protect. The report is also narrowly focused on targeting the governments as the perpetrators of mass atrocities and violators of human rights. There are actors other than states that commit crimes against humanity. Armed rebel groups in the Congo and Sierra Leone are widely known for their crimes against humanity, including killings, tortures and rapes. In addition, armed groups can provoke the government into a military crackdown in order to trigger external humanitarian intervention. This is exactly what happened in Kosovo in 1998 when the Kosovo Liberation Army used violence to deliberately provoke reprisals by the Serbian government that finally drew in NATO intervention forces in support of their cause of independence.

The UN General Assembly debated the R2P doctrine in its 2005 World Summit. Reactions to the doctrine varied. The non-aligned countries viewed it as a sophisticated political and diplomatic tool of the West to legitimize military intervention in non-Western countries. India’s then ambassador to the UN, Nirupam Sen, characterized it as an ideology of “military humanism”. John Bolton, the US ambassador to the UN at the time, rejected the idea of any legalobligation to respond to mass atrocities and insisted on retaining US freedom to decide when and where to take actions on humanitarian crises. Nevertheless, General Assembly members unanimously endorsed the R2P doctrine in the World Summit Outcome Document but in a much diluted version. The obligationto intervene, promoted by the ICISS report, was reinterpreted as a moral responsibility to intervene.

From 2001 to 2011, R2P remained dormant; it was not invoked with regard to situations in Darfur, Gaza or Somalia despite evidence of war crimes and crimes against humanity

Articles 138 and 139 in the World Summit Outcome Document declare the international community’s collective responsibility to protect peoples from the four crimes of genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity through diplomatic, humanitarian and other peaceful means in keeping with Chapters VI and VIII of the UN Charter. Article 139 speaks of collective action through the Security Council under Chapter VII should peaceful means fail and the government in question is unable or unwilling to stop the aforementioned four crimes. It makes no explicit reference to the use of force as the first step in changing a regime or unseating a government that violates human rights or commits mass atrocities.

Yet, a clear strategy outlining the steps to stop the crimes of genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity was lacking. The 2009 report of the secretary-general, “Implementing the Responsibility to Protect” suggested three specific pillars, drawn from the World Summit Outcome Document, to guide R2P implementation measures. The first pillar is the responsibility of individual states to protect their peoples from all types of gruesome crimes. Whenever a state manifestly fails to discharge its protection responsibilities, the international community steps in as the second pillar. The responsibility of the international community is only to encourage and assist the failing state to carry out its protection responsibilities better. The third pillar is about collective responses under the UN Charter to bail out the failing state(s) in a “timely and decisive manner”.

The UN member states debated the secretary-general’s report in July 2009; they accepted the idea of implementing R2P but there was no agreement on the legal nature of the concept at the international level. The conclusion from the debates was that every state had a legal responsibility to protect its own citizens but that there were no legally binding obligations to protect citizens of other states beyond its borders. The original version of moral responsibility to protect, as put in the 2005 World Summit Outcome Document, was retained.

From 2001 to 2011, R2P remained dormant; it was not invoked with regard to situations in Darfur, Gaza or Somalia despite evidence of war crimes and crimes against humanity committed by internal and/or external parties. The Security Council reaffirmed its support for R2P for the first time in Resolution 1674 adopted in April 2006, which lent its support to Articles 138 and 139 of the World Summit Outcome Document. Two permanent members of the Council –China and Russia—and three non-permanent members—Algeria, Brazil, and the Philippines—expressed reservations but Resolution 1674 was passed unanimously. Actions against the four crimes of genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity were expected as a result, but what followed was simply humanitarian negligence by the Security Council.

In February 2009, the World Council of Churches called upon the international community to invoke R2P to stop Israeli war crimes against Palestinians in Gaza, but the call went unheeded; and was ignored by the Security Council while some permanent members wrongly sought to justify their abuses in the name of R2P. The US attempted to misappropriate R2P in 2003 to give a humanitarian gloss for its invasion of Iraq; Russia claimed that its 2008 war against Georgia was to stop genocide by the Georgian troops and was thus a necessary R2P action; and France urged the Security Council to invoke R2P to allow forcible delivery of humanitarian aid to the victims of Cyclone Nargis that devastated Myanmar in 2008. All three cases were roundly condemned and rejected by the international community. The developing countries became more and more skeptical about the real purposes behind the R2P doctrine.

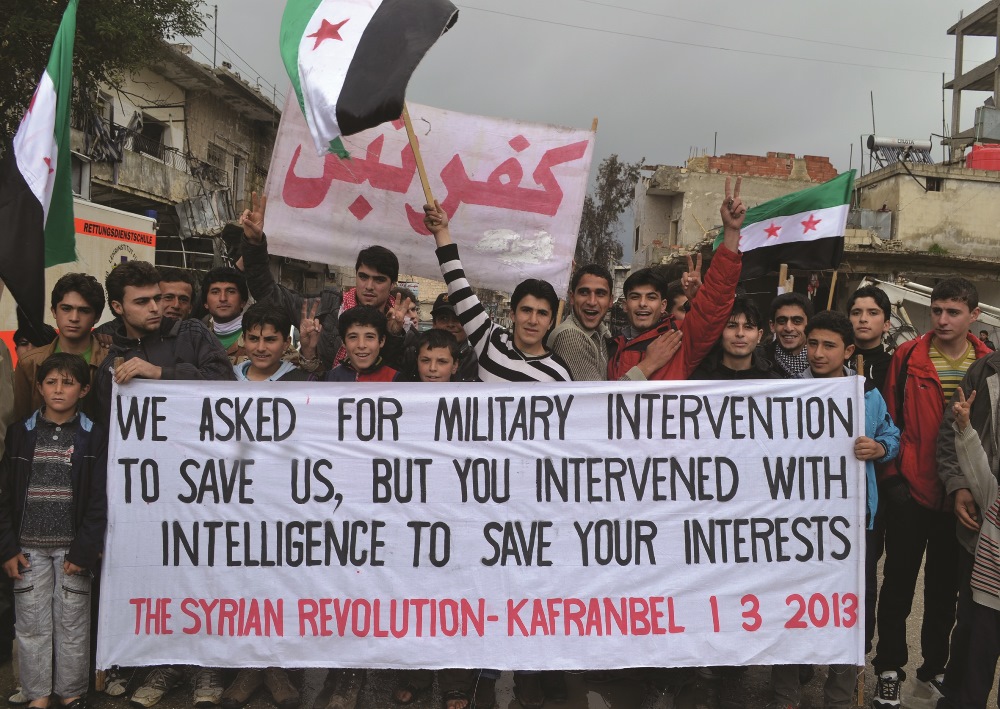

A handout picture shows Syrian anti-government protesters holding a banner against the international community’s reluctance to arm rebel forces. | HO / SHAAM NEWS NETWORK / AFP

A handout picture shows Syrian anti-government protesters holding a banner against the international community’s reluctance to arm rebel forces. | HO / SHAAM NEWS NETWORK / AFP

R2P and the Arab Spring

The Arab Spring brought R2P back on the international stage in February 2011. The popular uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt created no serious international concerns to intervene. In Libya, anti-Gaddafi revolts, however, turned violent at a faster pace. The Security Council quickly adopted Resolution 1970 on February 26, 2011, just ten days after the revolts broke out in Benghazi in eastern Libya. The resolution warned Gaddafi of the consequences of using force against civilians and imposed an arms embargo on Libya. After a short gap of only three weeks, the Council approved another resolution, Resolution 1973, on March 19, 2011, to create the legal context for military intervention against Gaddafi government, with abstentions from China, Russia, Brazil, India, and Venezuela. The new resolution established a ‘no-fly zone’ over Libya and approved “all necessary measures” to protect Libyans. NATO’s humanitarian air operations started shortly after Resolution 1973 was passed, which lead to the death of Gaddafi and the bringing down of his government on October 20, 2011.

The way the Security Council reacted so quickly to the Libyan situation surprised many people as equally or more appalling human sufferings in Bahrain, Syria and Yemen were ignored for an unexpectedly long time. It took nearly a year for the same Council to pass a resolution on Yemen (Resolution 2014 of October 21, 2011) that called for no R2P actions but for a Yemenis-led political reconciliation process. The obvious question is: Why was the Gaddafi government targeted rather so quickly by a Security Council led by the US, the UK and France?

Condoleezza Rice, the former US National Security Advisor and Secretary of State, once branded Gaddafi a model “modernist dictator”. In the wake of the 2003 US invasion of Iraq, Gaddafi agreed to dismantle his weapons of mass destruction program and went into the Western fold. Although relations between the Gaddafi regime and the West eased after 2003, he still was a dictator and not that dependable of an ally. The removal of Gaddafi from power, the West concluded, would open up Libya as a huge market for oil and investments. France, the US, and the UK started targeting Gaddafi forces after they had reached oil deals with the anti-Gaddafi National Transitional Council (NTC).

The toppling of Gaddafi in October 2011 was apparently a success for R2P, but viewed critically it has done irreparable damages to the R2P doctrine in, at least, three distinct but interrelated ways: the quick resort to military force, the double commission of war crimes and crimes against humanity, and the morally and ethically unacceptable post-intervention Western policy towards Libya.

The toppling of Gaddafi in October 2011 was apparently a success for R2P, but viewed critically it has done irreparable damages to the R2P doctrine

Force was no doubt used against the Gaddafi government with an astonishing speed. And that was in clear violations of relevant provisions in the ICISS report, the 2005 World Summit Outcome Document and the 2009 report of the secretary-general. The ICISS report recommends the use of force only as a last resort, after all political, diplomatic and non-military measures to prevent atrocities against civilian populations have been used and exhausted. Military force can be used only in “extreme and exceptional cases” (Article 4.10). There must be concrete evidence that the case is really extreme and that it requires international collective actions. It is disputable how Libya became an extreme case so quickly, while Darfur, Somalia, Syria or Yemen has not. A similar position of exhausting all non-military means before intervention was taken by UN members in the 2005 World Summit Outcome Document (Articles 138 and 139). The second pillar of the 2009 report of the secretary-general—the responsibility of the international community to assist the state in question—was also skipped.

The African Union initiated a reconciliation process between the Gaddafi government and the rebel NTC in April 2011. France, Britain and the US did everything to effectively sabotage the reconciliation process. On April 15, 2011 British Prime Minister David Cameron, former French President Nicolas Sarkozy, and the US President Barack Obama published a joint worldwide op-ed rejecting Gaddafi from playing a part of any future arrangement in Libya, though they said their objective was not to unseat Gaddafi by force. That put them in the position of being the actual deciders in Libya with the NTC playing a secondary role. Not only that, France supplied arms to the NTC-backed rebel fighters in clear violation of Resolutions 1970 and 1973 that imposed an arms embargo on all parties in Libya. The ultimate objective was, indeed, a change of regime in Libya. This prompted Hardeep Singh Puri, India’s ambassador to the UN in 2011, to brand NATO as the “armed wing” of the Security Council, dedicated not to protect civilians in Benghazi but to overthrow the government in Tripoli.

R2P has been largely discredited by Western abuses in Libya, the immobility of the Security Council over Syria, and the Council’s bizarre indifference to Bahrain and Yemen

Gaddafi forces were accused from the beginning of committing war crimes and crimes against humanity. Nobody would defend what Gaddafi did to his own people, but the realities on the ground were much exaggerated. According to one estimate, some 100 Libyans were killed before the rebels took up arms but tens of thousands died after NATO had started its bombing campaigns. Libyan casualties resulting from NATO bombings have been well reported by Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, the BBC, and the New York Times. The casualty figure, according to the BBC, was between 2,000 and 30,000. This clearly proves that NATO actually committed war crimes and crimes against humanity in Libya. So the application of R2P in Libya tragically resulted in the double commission of crimes—the simultaneous killing of Libyan civilians by the Gaddafi forces and by the so-called protector, NATO.

No less ominous was how the Security Council and NATO overlooked the atrocities and crimes committed by NTC rebel forces. The international media also failed to report the crimes. Independent investigations by Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and the International Commission of Inquiry on Libya, set up by the UN Human Rights Council, found rebel fighters guilty of conducting arbitrary arrest, torture and unlawful killings. The rebels burnt down almost the whole city of Tawergha, near Misrata, and killed many of the black African residents of the town on the ground that they had supported Gaddafi during the civil war. Some 53 Gaddafi supporters were summarily executed in Sirte. Neither the Security Council nor NATO has launched any investigation to probe the rebels’ crimes and bring them to justice.

NATO left Libya after Gaddafi was killed, leaving behind a NTC plagued with internal divisions and unable to address serious issues of national reconciliation and unity. The security situation deteriorated sharply and Libya descended into a hell of lawlessness with 125,000 armed militias who have continued to control different parts of the country and clash against each other. The central government is often helpless. Individual armed brigades have detained more than 8,000 pro-Gaddafi supporters who have remained outside the control of the central authority, which clearly lacks an internal security infrastructure of trained prosecutors, committed police force and judicial staff to try the perpetrators of crimes. Post-Gaddafi Libya has been struggling hard to maintain itself with little or no help from the interveners or the international community. The responsibility to rebuild Libya in the post-intervention period was forgotten.

Post-Libya Intervention

The abuse and misuse of Resolution 1973 by Western interventionists in Libya has produced two major impacts on international relations, namely a breakdown of great power consensus on R2P achieved through the resolution, and a strengthening of the suspicions by the majority Asian, African and Latin American countries that R2P is a new cover for Western neo-imperial domination and liberal warmongering.

The breakdown of consensus on R2P post-Libya has seen its manifestations in the Security Council over Syria. Two issues that sharply divided the permanent members of the Security Council were the West’s policy of regime change in Libya, and taking side with the rebel fighters. Instead of abiding by the mandate of Resolution 1973, NATO acted as the air force of the anti-Gaddafi rebels and bombed the civilian population. It looked more like a NATO war against the Gaddafi government. China and Russia, who have obvious strategic and commercial interests in Syria, used such abuses to defeat two Security Council resolutions on Syria. Power politics has come to its full play at the costs of human sufferings in Syria. Some 70,000 Syrians have already been killed and hundreds of thousands have been displaced and made refugees in neighboring countries while the great and regional powers have been trying to protect and promote their deep-rooted respective interests. The West and the Arab League are seeking a Syria militarily and diplomatically cut off from Iran, Russia highly values Syria as a long-term defense equipment buyer and for maintaining naval presence in the Syrian Mediterranean sea port of Tartus, and Iran is determined not to let the Bashar Al-Assad government fall as that has the potential of seriously disturbing the regional strategic balance against Tehran.

The credibility of the Western R2P interveners is also at stake here. Apart from their abuses in Libya, the US and the UK fought an illegal war in Iraq from 2003 to 2011 that killed, maimed and wounded nearly a million Iraqis. It made many states and peoples around the world suspicious about their real motives behind seeking Security Council resolutions to facilitate intervention in Syria after what happened in Libya. Equally important to note has been the West’s indifference to the gruesome human costs of the Arab Spring in Bahrain and Yemen. There have been no efforts to condemn, let alone for Security Council actions to halt, the killings and tortures of pro-democracy activists by government forces in these two countries. Interestingly, Bahrain hosts the headquarters of the US Fifth Fleet and Yemen’s Ali Abdullah Saleh has extended all-out cooperation to Washington’s fight against al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. The standard R2P policy of the West then looks like this: take off those who oppose, accommodate those who comply, even if the latter group happens to be brazen dictators and notorious violators of human rights.

Clearly, R2P has been largely discredited by Western abuses in Libya, the immobility of the Security Council over Syria, and the Council’s bizarre indifference to Bahrain and Yemen. The hidden policy of regime change in Libya has, in fact, killed the R2P doctrine. Additionally, changes in the global power structure, manifested in the ongoing shift of global economic and financial power from the North to the South, and the gradual emergence of multiple centers of powers (from the G7 to the G20, for example) coupled with a relative US decline has meant that the West has limited maneuverability to undertake R2P actions in the future. Liberal humanitarianism will continue to appeal to our collective human conscience to alleviate the sufferings of fellow humans at home and abroad, but it is doubtful whether there will be any more Libya-type humanitarian military intervention in the years and decades to come.