Mass protests in Maidan, the central square of Kyiv, during the bitter cold winter of 2013-2014, known as ‘Euromaidan’ or ‘Revolution of Dignity’ were non-violent for more than two months. The demonstrations began when, under Russian pressure, former President Viktor Yanukovych abruptly resisted in signing the long promised Association Agreement with the EU. However, when President Yanukovych, reputed for his corruption and authoritarian style, responded to the peaceful protests by violent repression, Euromaidan quickly moved beyond its initial slogans and demanded the president’s resignation. In February 2014, after security forces started to shoot protesters, Ukraine became one of the only countries in the world where a hundred people died “under the EU flags” defending democracy and the European choice. In this context, according to the agreement signed on February 21, 2014, between the opposition and President Yanukovych, the parliament returned to the 2004 constitutional reform and, consequently, combined a parliamentary-presidential form of government. The 2004 constitutional reform had previously been unconstitutionally abolished by President Yanukovych in 2010 and its restoration was among the main demands of the Euromaidan.

Yanukovych violated this agreement: he did not sign it and fled to Russia. Immediately, the early presidential elections were scheduled by the parliament for May 2014. However, prospects for a successful resolution of these domestic problems were threatened by external factors: the annexation of Crimea by Russia (it is the first case of an annexation in Europe occurring since the end of World War II1), and the subsequent Russian military infiltration2 in Donbas (the two eastern regions of the country). The need to quickly elect a legitimate and internationally recognized President and the need to resist Putin’s attempts to split Ukraine largely determined both the spirit of the electoral campaign and its results. Petro Poroshenko, one of prominent ‘Maidan’ supporters, a businessman and the owner of the opposition TV Channel 5, won a clear cut victory in the first round with 54% of the votes.3

No Alternative to Early Parliamentary Elections

First of all, “reset of power” was a popular slogan of the ‘Maidan’ movement. But the new cabinet led by Arseniy Yatsenyuk, one of the Maidan leaders, had to rely on an unstable majority in the Ukrainian parliament (the Rada), elected in 2012 under the previous regime. This majority had to be created with a large number of defectors from the ‘Party of Regions,’ previously headed by Yanukovych. It was clear that the old composition of the parliament no longer reflected the real picture of the public’s attitudes and electoral preferences.

Second, MPs from the previous majority (Party of Regions and the Communists) voted on January 16, 2014, for the so-called ‘draconian laws,’ in a way which violated all the procedures and regulations, as well as the Constitution. These laws sharply restricted independent mass media, civil society activists, think tanks, and NGOs. In fact, it de-facto legalized large-scale repression against all who were opposed to Yanukovych. According to the views of the absolute majority of Ukrainians, these MPs had neither the legal nor the moral right to retain their seats. Thus, the dissolution of the parliament was supported by 60% of the protesters in Kyiv in February 2014.4 Moreover, the anti-democratic nature of the Party of Regions and the Communists was only strengthened when the new facts revealed their support for the Russian-backed separatists in Donbas and the annexation of Crimea.

Finally, early parliamentary elections were favorable for a number of political forces, including the new ones, which were in the process of forming after the Maidan demonstrations. Although Poroshenko, received tremendous support in the presidential elections, to effectively govern, he needed his own majority in the parliament. Once the 2004 constitutional reforms were reinstated, the President, whose powers were limited by the new mixed form of government, was looking to a loyal cabinet formed on the basis of a parliamentary coalition. To obtain this political goal, it was advantageous to have early elections before the President’s popularity had a chance to wane under the pressures and decline owing to the difficult economic conditions in times of war. Still, the problem remained that Poroshenko did not have his own political party. Thus, he had no automatic political and parliamentary majority. He had to negotiate with UDAR (“Strike”), led by Vitali Klitschko - the famous world champion boxer and now mayor of Kyiv as well as other political forces. A new pro-presidential political party called “Petro Poroshenko Bloc” (which UDAR joined) was formed.

A majoritarian system, in this context, is ineffective and unsuitable, as it distorts the real picture of the ideological and electoral preferences of the society

At the same time, a split emerged within ‘Batkivshchyna’ (the ‘Motherland’ party); previously the main force of the opposition to Yanukovych, who imprisoned Yulia Tymoshenko - the charismatic party’s leader, on politically motivated charges. The new wing of the party was now headed by Oleksandr Turchynov and Arseniy Yatsenyuk. They became, respectively, speaker of the Rada and Prime Minister, after Yanukovych was ousted and fled. But they failed to reach an agreement with the party leader Yulia Tymoshenko, who after being freed from prison gained the second place in the presidential contest with only 14%. While pre-term elections were favorable to the new wing of “Batkivshchyna,” the “old” wing was not interested in participating to the process. Tymoshenko perceived that it was more logical to wait it out until the President’s popularity diminishes. Still, all of the presidential candidates during their campaign stressed their support for early parliamentary elections. It was a politically necessary strategy if they did not want to lose the support of the Ukrainian voters, as there was an overwhelming demand for change.

Fully in accordance with Ukrainian Constitution, President Poroshenko called for early parliamentary elections to take place on October 26, 2014.

New Parliament Elected Under the Old Rules

Demand for early parliamentary elections also included a demand for changes in the electoral law, specifically, the establishment of a proportional electoral system with open party lists. During the 2012 elections, Yanukovych decided to abandon the proportional system and replace it by a mixed electoral system: half of the MPs were elected on party slates, while the second half of the MPs were elected in single-mandate majoritarian districts. Majoritarian districts enabled the authorities to manipulate the system in two-ways. First, it made possible the election of latent supporters of the ruling party, as so-called “self-nominated” candidates. Second, such an electoral system opened additional opportunities for falsifications and violations in majoritarian districts, especially rural districts remote from the center where it was much more difficult for electoral observers to control the process. As a result, in 2012, three opposition forces won party slates and collected more than 50% of the votes, while the Party of Regions obtained 30%, and the Communists managed to garner13%. But, a parliamentarian majority was formed by the Party of Regions and the Communists combined, based on the majoritarian MPs.

The type of electoral system only confirms the general rule, well known for researchers of transitional societies: in young democracies a proportional electoral system has an important function of political and ideological structuring both for the society (electorate) and political parties. A majoritarian system, in this context, is ineffective and unsuitable, as it distorts the real picture of the ideological and electoral preferences of the society.

Not surprisingly, changing the electoral system and holding early parliamentary elections were among the main promises of Petro Poroshenko and other democratic presidential candidates. However, this promise was not fulfilled and the old mixed electoral system was kept in place for two main reasons:

First- President Poroshenko wanted to gain the largest faction in the parliament. The most reliable mechanism to achieve this goal was to preserve the majority component of the electoral system as the self-nominated majoritarian candidates connected to the business sector would naturally join the winner in the parliament. In addition, voters were often swayed to choose a certain party list because of the personality or charisma of the party leader. Therefore, the President who enjoyed a high level of popularity expected that his party would benefit from a high degree of support, both in the proportional and majoritarian systems.

For the political parties, a short electoral campaign meant competition, not so much of ideas and programs, but the use of political technologies for the effective mobilization of voters

Second- The need for compromise with the majoritarian electoral system for MPs in the existing “old” parliament. Cancellation of the majoritarian component in the context of Ukraine’s mixed electoral system would have meant that many MPs ran the risk of not being re-elected. Therefore, it was very unlikely that most MPs would vote for a new electoral system. Moreover, democratic factions needed to ensure the loyalty of the majoritarian half of the parliament to pass urgently needed measures. The best example was the ratification of the Association Agreement with the EU in September 2014. To pass the agreement, the democrats needed the votes of former members of the Party of Regions. At the same time, the involvement of Russian regular troops in Donbas in August 2014 meant that unity in the parliament would be essential if urgent and immediate decisions needed to be adopted.

However, maintaining the previous electoral law, which included a mixed electoral system, a 5% electoral threshold, and banning of blocs, was unfavorable for the new parties that had emerged during the Maidan. As a result, “new” faces in politics (civic activists, journalists, experts) decided not to unite under the banner of a new political party that would have represented the new “Maidan party,” as they were not sure to pass the 5% threshold. Instead, they ran on the party slates of more powerful political forces, including the presidential party “Poroshenko Bloc” and the prime-minister’s “People’s Front.”

Wartime Elections: Predictability and New Trends

For the first time in the history of independent Ukraine, elections were held not on the whole territory of Ukraine. The territory of annexed Crimea comprises 5% and the occupied areas of Donbass only 3% of Ukrainian territory. So, the number of seats, which would stay empty (until it would be possible to organize elections in these areas), only represents 27 mandates out of 450. Its main electoral impact on the Parliament was to decrease the electoral base for the Communists and the Party of Regions. However, as 2/3 of Donbas remained under Ukrainian control, this region received representation on both party slates and single-member constituencies.

Ukrainian society’s demand for “new faces in politics” and a “new quality of policy” materialized through “Samopomich” electoral support, which was evenly distributed throughout Ukraine

One of the most important features of this election was the reduction of the electoral campaign to 45 days. Under these circumstances for new candidates, running in single-mandate districts, chances to be elected decreased. For the political parties, a short electoral campaign meant competition, not so much of ideas and programs, but the use of political technologies for the effective mobilization of voters.

One thing was quite predictable: according to all forecasts, pro-European forces won the overwhelming victory, gaining in total almost 70% of the vote. For the first time in independent Ukraine, the Communist Party did not pass the threshold. This party served as the silent “junior partner” of the Party of Regions. Further, the Communist party was viewed by Ukrainian society as Russia’s “fifth column.”

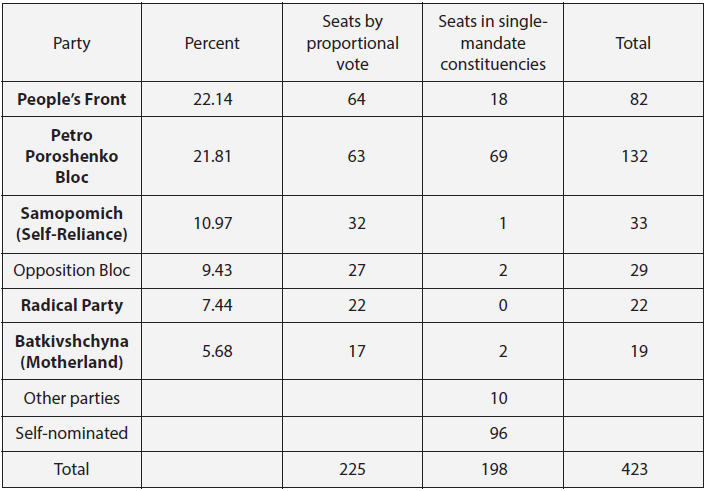

The first and the most important surprise of these elections was certainly the success of the “People’s Front” party, which took first place in the proportional part of the election, receiving 22.14% of the vote, slightly ahead of “Petro Poroshenko Bloc” (21.82%). It happened despite the fact that the Poroshenko Block was the undisputed front-runner of the race during the entire electoral campaign. The “People’s Front” articulated a very straightforward message to their potential voters: “Do you want to see Yatsenyuk as a prime minister? Vote for “PF”! This clear and concise, if not overly simplified, message proved to be very effective during the short electoral campaign.

At the same time, the electoral campaign of the president’s political force was built on the same principles that Poroshenko’s presidential campaign had been built: the need for unity5 and the consolidation of future coalition. However, only, obviously, around the president’s party. Despite a considerable decline in ratings, the “Petro Poroshenko Bloc” formed the largest faction in the parliament. This is true for a number of reasons, such as the majoritarian MPs joining this group (see the table).

Table 1. Result of the Early Parliamentary Elecetions of October 26, 2014

Parties associated with Euromaidan - in bold

Thus, there were two winners of the parliamentary elections: the two “parties of power.” It was a positive sign that in a time of war and economic crisis, Ukrainian voters did not follow populist slogans and trusted those who were in power. It also meant that the monopolization of power by one political force was unlikely; the president and prime minister had to work together.

The second important surprise emanated from a new political reformist force, “Samopomich” (Self-Reliance). This political movement managed similarly to the “People’s Front” to mobilize the voters during a rather short period of time. Until the end of October, “Samopomich” did not obtain more than the 5% threshold in the electoral polls but in the end obtained 11%! Ukrainian society’s demand for “new faces in politics” and a “new quality of policy” materialized through “Samopomich” electoral support, which was evenly distributed throughout Ukraine. It was able to overcome the threshold in all the regions of Ukraine, including Donbas.

Ukrainian Political Nation Consolidated

In general, Ukraine was traditionally a country politically divided between the east and the west. This split was artificially created in the interests of party-politics, as they tried to capture their own electorate. However, this tendency has started to subside. Nevertheless, regional divides still endure. The center and the west of the country support pro-European forces while it’s less the case in the east and south. At the same time, the “Opposition Bloc,” created on the ruins of the Party of Regions, received its main support from the east and south. A more detailed study of regional voting on party slates shows that the south, which traditionally supports Yanukovych, saw the “Maidan” democratic parties beat out the Opposition Bloc and the Communists 2,5 : 1. Even in the east, the “Maidan” parties were ahead of their opponents. These results testify to the fundamental shifts in the political orientations of Ukrainians after Euromaidan7.

Former Ukrainian prime minister and opposition leader Yulia Tymoshenko delivers a speech during a convention in Kiev on March 29, 2014. |AFP / Genya Savilov

Former Ukrainian prime minister and opposition leader Yulia Tymoshenko delivers a speech during a convention in Kiev on March 29, 2014. |AFP / Genya Savilov

The paradox is that despite the war in Donbas, Putin’s aggression actually cemented political Ukrainian identity, notwithstanding the linguistic or religious origins of Ukrainians. Euromaidan confirmed that modern Ukrainian nationalism is a territorial not an ethnic one and “inclusive” rather than “exclusive.” In Maidan, every day started with a multi-confessional common prayer. Russian-speakers and locals from Donbas comprise a substantial part of volunteer battalions fighting in Donbas for the territorial integrity of Ukraine. The results of both presidential and parliamentary elections have also shown that “the heavy focus on right-wing radicals [in Maidan] in international media reports was misleading.”8 In the parliamentary elections The Right Sector secured only 2% (just compare to 25% of the National Front in France during the elections to the Europarliament). The far right elected only 3 MPs out of 450. The nationalist center-right “Svoboda” (Freedom) also did not overcome the barrier.9 And, despite the allegations of the Russian media, no far-right parliamentarians obtained any seats in the government.

Pro-European Coalition Government

Ukrainian Constitution gives 30 days for the formation of a coalition and 60 days for the formation of the cabinet, from the date when the new parliament enters into session. Despite initial trepidations and concerns, a coalition and a cabinet were created within 5 days. Five out of the six political parties that formed the parliament signed the coalition agreement with a detailed program of broad reforms. However, the “Opposition Bloc,” as the successor of Yanukovych’s Party of Regions, was logically not included in the coalition process. The new coalition received 302 seats, which potentially represents a constitutional majority (300 out of 450). Moreover, a broad coalition should prevent the monopolization of power by one political party or faction. Arsenii Yatseniuk kept his place as Prime Minister while Volodymyr Hroisman (Poroshenko Bloc) became the Speaker.

Of course, under the current political configuration, the President, who possesses the largest faction in the parliament, could try to extend his latent powers. In this context, competition between the Prime Minister, on the one hand, and the President, on the other, is potentially possible. However, it is unlikely to take the disastrous turn it had taken after the 2004 Orange Revolution between Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko and President Viktor Yushchenko. There are a number of differences. First, the present economic and wartime context are pushing the President and Prime Minister to work together. Their mutual cooperation is a pre-requisite for Western support and the aid from international financial institutions. Second, alliance with former members of the Party of Regions, known now as the “Opposition Bloc,” with its notorious MPs who supported the ‘draconian laws of January 16th,’ would be politically suicidal for any party of the current coalition.

Establishing an effective and sustainable Ukrainian democracy represents best way to resist the political and military encroachment of Putin’s regime

The coalition based on the ‘Coalition Agreement’ has agreed that European and Euro-Atlantic integration are at the top of Ukraine’s foreign policy priorities. These new foreign policy objectives reflect the dramatic shift in Ukrainian society over the past year. Previously, in Ukraine, supporters of NATO membership were always a minority. However, the non-bloc status adopted under Yanukovych in 2010 did not prevent Russia’s unprecedented economic and information attack against Yanukovych himself in the summer-fall of 2013 when he was about to sign the Association Agreement with the EU. Logically, since the annexation of Crimea, the number of NATO supporters has exponentially grown. According to the November 2014 poll of the “Rating Group,” if a referendum was held, it would be 51% in favor and 21% opposed to joining NATO. Support for EU membership is even higher. In July 2014, 61% of Ukrainians would say “yes,” while only 20% would support joining the Customs Union with Russia10.

The non-bloc status has been cancelled by the new parliament in December 2014. At the same time, there is an understanding among Ukrainian politicians and experts that NATO and the EU membership are not on the agenda right now. The stress now is on developing cooperation with NATO and implementing the recently ratified Association Agreement with the EU. And the best option for that is for Ukrainian government to roll up its sleeves by implementing long-awaited domestic reforms in Ukraine, including fighting corruption, limiting the role of oligarchs, and providing for the judicial reform and the rule of law.

Conclusion

Establishing an effective and sustainable Ukrainian democracy represents best way to resist the political and military encroachment of Putin’s regime. However, Putin’s plans to either control all of Ukraine or at least to split it have so far failed. On the contrary, early presidential and parliamentary elections in Ukraine were held. They were recognized by the international community as free and fair. Candidates of the Yanukovych’s party also participated; although voter support for this party dropped dramatically from 30% to 9.5%. Another development on the electoral scene is that both the far left (the discredited Communists) and the far right did not meet the 5% voter threshold.

The new elections produced an overwhelming pro-European majority even if there are still risks of splits in the coalition. However, for the parties, which stood in Maidan, there is a clear choice: to win together or to lose together. The challenges ahead remain great, as the President and the new government need to conduct unpopular reforms in the context of a war-time economy when Russia continues its efforts to destabilize the fledgling Ukrainian democracy.

Ukraine-EU Association Agreement provides a roadmap for reforms. However, Ukraine deeply needs the international community’s support. Especially, after annexation of Crimea and Russia’s attempts to change territorial borders in the east of Ukraine. The framework for the necessary first steps to finding a solution is provided by the Minsk Trilateral Agreements, signed in early September 2014 by Ukraine, Russia, and the OSCE. The Agreements outline the ceasefire, the withdrawal of foreign mercenaries, illegal military formations from Ukraine, and the OSCE control over Ukrainian-Russian border. At this juncture, the implementation of the Agreements still remains to be seen.

Endnotes

- It was clear violation of the 1994 Budapest memorandum: Ukraine gave up its nuclear arsenal (the third largest in the world) in exchange for “security assurances” and territorial integrity from the US, the UK, and… Russia. On March 27, 2014, the UN Assembly General resolution on territorial integrity of Ukraine was supported by 100 countries, including Turkey, with only 11 – against (including Northern Korea, Sudan, Syria, Bolivia, Cuba, Nicaragua, Zimbabve, Venezuela, and Belarus).

- See, for example, April 1, 2014 Statement of the NATO-Ukraine Commission: (“We, the Foreign Ministers of the NATO-Ukraine Commission, are united in our condemnation of Russia’s illegal military intervention in Ukraine.”) http://www.nato.int/cps/en/

natolive/news_108499.htm; June 14, 2014 NATO Releases Imagery: Raises Questions on Russia’s Role in Providing Tanks to Ukraine http://aco.nato.int/statement- on-russian-main-battle-tanks. aspx; Gen. Philip Breedlove, Supreme Allied Commander, Europe, “Who Are the Men Behind the Masks?”, Apr. 17, 2014 http://aco.nato.int/ saceur2013/blog/who-are-the- men-behind-the-masks.aspx - For more, see, Haran O., Burkovsky P. The Poroshenko Phenomenon: Elections and Challenges Ahead. PONARS Memo No.336, Aug. 2014 (www.ponarseurasia.org/node/

7184) - Maidan –December and Maidan - February: what has changed (www.dif.org.ua/en/

publications/press-relizy/vid- mchi-sho-zminilos.htm) - No. 5 on the party list was Mustafa Cemilev (Qirimoglu), who spent 15 years in Soviet prisons and then was the head of the Crimean Tatar Mejlis for 25 years. After Russia’s annexation of Crimea, several Crimean Tatar leaders, including Mustafa Cemilev, have not been allowed to come to Crimea (as it was under the Soviet Union)! So, the no. 5 of Poroshenko’s list was quite symbolic, demonstrating his block’s solidarity with Crimean Tatars.

- See official results, http://www.cvk.gov.ua/pls/

vnd2014/wp611?PT001F01=910 - Members of the Party of Regions obtained better results in single-mandate districts, as they used traditional schemes to buy votes. This irregular electoral practice further illustrates the need to move towards a proportional electoral system with open party slates.

- See, the public statement prepared by Dr. Andreas Umland, German academic expert on the far right, and signed by forty Ukrainian and Western academic experts. (http://blogs.pravda.com.ua/

authors/haran/52f0b14c4cc77/) - True, in the 1990s, “Svoboda” started as a far right force but by the elections of 2012, it moderated its position and moved towards the conservative center-right.

- For more, see the data from the public opinion polls, conducted by the “Rating Group,” http://ratinggroup.com.ua