Fifteen years ago, South America witnessed a remarkable example of how regional diplomacy can help a country overcome a profound political crisis. Polarization and consequent tensions regarding Venezuela’s political direction grew in the years after Hugo Chávez’s election in 1999. They spiked in 2002, when a group of businessmen and military leaders staged a short-lived coup d’état. Chávez returned to power within forty-eight hours. Governments in the region not only condemned the move, but also closely followed the situation and pressured both the Venezuelan government and the opposition to re-establish a dialogue in the coup’s aftermath. Brazil’s President Fernando Henrique Cardoso advised Chávez to grant leading opposition figures involved in the plot amnesty, arguing that including all factions were crucial to promote a broad national dialogue. When oil workers went on strike against Chávez in late 2002, Cardoso provided the Venezuelan government oil shipments to avoid an economic collapse. Under President Lula, who took office in January 2003, Brazil continued to play a key role in helping its neighbor overcome polarization, leading the group “Friends of Venezuela,” consisting of several Latin American governments. President Lula insisted on including the United States and Spain in the group, which helped bring the government and the opposition together.

Entirely dependent on oil exports, both presidents Chávez and Maduro had used high oil prices to finance social programs, which reduced poverty but could not be sustained in a more adverse macroeconomic scenario

Brazil’s move proved crucial as it convinced the opposition to seriously engage in the debates. Lula may have been a left-wing president, but he was still seen as a legitimate and relatively impartial mediator by the center-right opposition in Venezuela. The United States’ inclusion was particularly remarkable considering Washington’s controversial and unhelpful role during the 2002 coup –contrary to Venezuela’s South American neighbors– the U.S government seemed to signal cautious support to Pedro Carmona, who had led the coup attempt, during his 48 hours in power. At the time, Brazil understood that an eclectic grouping with the representation of all sides of the ideological spectrum was necessary to be credible in Venezuela and jointly exert pressure to avoid a violent confrontation.

Ten years later, violent confrontation yet again emerged in Venezuela. Polarization had never been fully overcome but worsened considerably in 2014, when large-scale anti-government demonstrations shook the country. More than 30 protesters died during the clashes, and more than 1,500 were detained. In 2016 and 2017, protests and repression reached new dimensions, and the government adopted a more explicitly authoritarian strategy, sidelining the opposition-dominated parliament, and imprisoning a growing number of opposition figures. This scenario was accompanied by a profound economic crisis, the result of years of mismanagement and excessive public spending during years of high commodity prices. Entirely dependent on oil exports, both presidents Chávez and Maduro had used high oil prices to finance social programs, which reduced poverty but could not be sustained in a more adverse macroeconomic scenario. When oil prices halved from over $100 per barrel to around $50, the Venezuelan government paid the price for its previous largesse. With the government unable to pay for imports, price controls were imposed, which led to dramatic product shortages, severely affecting the poor, who were unable to obtain even basic goods on the black market. As a consequence, a significant part of the population no longer had access to three meals a day, a plight that continues today. Public hospitals across the country lack even basic medicines. Looting of supermarkets has become more common. People with chronic diseases that require medication are forced to emigrate if they want to survive. With the world’s worst-performing economy and the highest inflation rate on the planet, oil-rich Venezuela is sliding ever deeper into an economic catastrophe from which the country will take years, if not decades, to overcome.

Amid the political and economic crisis in Venezuela, opposition activists and riot police clash during an anti-government protest in Caracas on July 4, 2017. | AFP PHOTO / JUAN BARRETO

Amid the political and economic crisis in Venezuela, opposition activists and riot police clash during an anti-government protest in Caracas on July 4, 2017. | AFP PHOTO / JUAN BARRETO

Why have governments in the region been unable to halt Venezuela’s decline, contrary to their positive influence in 2002 and 2003? There are four reasons why regional diplomacy failed.

First of all, the situation in Venezuela has deteriorated dramatically, and can no longer be compared to the problems present fifteen years ago. While there was a near equilibrium of forces between government and opposition, power is now concentrated almost exclusively with the government and the armed forces. Today, there is growing evidence that Nicolás Maduro’s gamble of creating a constituent assembly has paid off. The opposition is weak and divided, and the armed forces are reaping unprecedented riches by controlling the distribution of food and medicines, having little interest in changing the status quo. With many disillusioned citizens migrating to Colombia, Brazil, the United States, Argentina and Spain, and violence against protesters continuing unabated, the days of mass protests are unlikely to return in the near future.

Secondly, while Brazil was able to stand out as a mediator in 2002 and 2003, the Lula government increasingly acted, along with Argentina, as one of Chavismo’s key defender in multilateral fora, even at a time when Venezuela’s government was showing increasingly authoritarian tendencies. Policymakers in Brazil and Argentina were shamefully silent when Hugo Chávez, temporarily empowered by high oil-prices, slowly dismantled his countries’ democracy. Juicy contracts for Odebrecht and other construction firms helped Brazil’s national champions strengthen their role in the region. The internationalization of Brazilian capitalism became a trademark of Lula’s regional policy, and Venezuela became a key part of it. Chávez’s commitment to protecting democracy, Lula’s advisors privately recognized, was limited, but the economic interests at stake were just too great to risk losing an important client. At one point, Venezuela’s secret service found out that a large Brazilian construction firm had donated money to both Chávez's party and Venezuela’s opposition ahead of an election. Furious, Chávez is said to have threatened to expel the company from the country, and it took Lula’s personal intervention to solve the matter.

In 2012, former President Lula actively campaigned for the incumbent Hugo Chávez, which generated fierce criticism from opposition figures. As a consequence, Brazil was increasingly –and rightly– seen as a partial actor with limited legitimacy to help Venezuela overcome internal polarization. This fundamental reality did not change when Dilma Rousseff was impeached in 2016 and Temer assumed office. While the Venezuelan opposition viewed the change in a positive light, President Maduro decided not to recognize the Temer administration, which, he rightly suspected, would change course vis-à-vis Venezuela.

Governments in South America were unable to play a constructive role because of their economic influence in Venezuela declined at the expense of extra-regional powers. Today, the four most influential actors in Venezuela are China, the United States and Russia while Cuba still holds significant political influence

Thirdly, Brazil’s political crisis, which emerged in 2013 but reached unprecedented levels in 2014, helped generate a regional power vacuum. Lower commodity prices not only affected Venezuela, but Brazil and many other South American countries, where lower growth rates led to a decline in governments’ approval ratings and political instability, forcing governments to focus on internal matters. In Brazil, the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff led to polarization, and the Temer government was embroiled in corruption scandals from very early on. With extremely low approval ratings, foreign policy was relegated to the sidelines of the public debate, and the Temer government early on struggled to be recognized by several countries in the region, including Bolivia. Under these circumstances, building regional consensus to help Venezuela overcome the crisis seemed increasingly unlikely.

Finally, governments in South America were unable to play a constructive role because of their economic influence in Venezuela declined at the expense of extra-regional powers. Today, the four most influential actors in Venezuela are China, the United States and Russia while Cuba still holds significant political influence. Diplomatic attempts to help Venezuela restart a dialogue –among others by Spain’s former Prime Minister José Luiz Rodriguez Zapatero– failed because they did not recognize Beijing’s key role as President Nicolás Maduro’s largest and most stalwart financial supporter. China as a political actor can no longer be left out of the search for solutions to Venezuela’s profound political and humanitarian crisis. With the government in Caracas now essentially a pariah regime and several leading Venezuelan officials no longer able to travel abroad due to international drug trafficking charges, Chinese investments have translated into tremendous political and economic influence.

Opposition leaders have continuously promised to review the terms of Chinese loans, if they ever assume power, after Maduro adopted a series of questionable legal maneuvers to sign accords without congressional approval. Remarkably, these deals with China are no longer included in the yearly budget, making it impossible for the media or opposition politicians to assess them.1 Over the past decade, China has lent over $60 billion to Venezuela, most of which it pays back with oil shipments, and none of which includes policy conditions. The support does, however, provide privileges for Chinese companies in key sectors of the Venezuelan economy such as automobiles, telecommunications, appliances, and oil drilling, according to reports. A factor that is likely to further increase worries in China that a change of government in Venezuela would expose Beijing to the legal quagmire of having to renegotiate its deals.

Last year, when the Venezuelan government came relatively close to defaulting, Caracas pocketed half a billion dollars from the Russian state-run company Rosneft, which increased its stake in the Petromonagas joint venture. It is now one of the key investors in energy in Venezuela.

As Marianna Parraga and Alexandra Ulmer recently wrote for Reuters,

Rosneft currently owns substantial portions of five major Venezuelan oil projects. The additional projects PDVSA is now offering the Russian firm include five in the Orinoco –Venezuela’s largest oil producing region– along with three in Maracaibo Lake, its second-largest and oldest producing area, and a shallow-water oil project in the Paria Gulf, the two industry sources told Reuters. In a separate proposal first reported by Reuters last month, Rosneft would swap its collateral on 49.9 percent of Citgo –the Venezuelan owned, U.S.-based refiner– for stakes in three additional PDVSA oil fields, two natural gas fields and a lucrative fuel supply contract, according to two sources with knowledge of the negotiations.2

Yet the Russian-Venezuelan partnership goes far beyond oil. As Thomas O’Donnell points out, “Between 2012 and 2015, Russia sold $3.2 billion in arms to Venezuela, making it the number-two buyer of Russian arms globally during that period. And in October 2014, Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro pledged another $480 million to purchase 12 Sukhoi-30 jetfighters and to upgrade existing Sukhois in the Venezuelan fleet.”3

In addition to economic gains, however, Russia’s strategy also assures Venezuela’s support at multilateral meetings and on the international stage in general at a time when Moscow continues to suffer from diplomatic isolation. An episode two years ago makes this clear. On May 9, 2015, Russia celebrated its victory over Nazi Germany 70 years earlier with the biggest parade of its kind since the collapse of the Soviet Union. The event, however, took place on the midst of a delicate geopolitical moment, with most Western leaders –including Barack Obama, David Cameron and Angela Merkel– declining the invitation to join the festivities due to Russia’s controversial role in Ukraine. Russian diplomats urged leaders from around the world to come right until the final days before the event, signaling how much a strong international presence meant to Putin who wanted to show his population that he was not isolated on the international stage.

At the same time, the United States’ influence in Venezuela is shrinking. In July, U.S. President Donald Trump promised “strong and swift economic actions,” should Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro go through with the July 30 vote to select delegates to the constituent assembly. Indeed, after the creation, the United States began to adopt economic sanctions that will hurt the Venezuelan economy. Those, however, who hope for swift U.S. action –for example, in the form of an oil embargo– are profoundly mistaken about its effects. Supporters of such a move argue that the havoc caused by broad sanctions would quickly lead to Maduro’s ouster, setting the stage for a return to democracy. Yet with the Venezuelan government desperately in need of foreign culprits for the country’s economic woes, a U.S. oil embargo would provide the ideal excuse for Maduro.

As is the case with Cuba, being the target of the U.S. sanctions tends to cause the so-called “rally ‘round the flag’” effect, increasing the government’s approval ratings and lending more credibility to the claims that the real cause of Venezuela’s problems is foreign meddling.4 With the armed forces already in control of national food distribution, those in power would not only earn even more money –due to even greater scarcity– but also use the increased scarcity to literally starve opposition strongholds, adding to the tremendous suffering of Venezuela’s population. It would also poison U.S.-Latin American relations for years to come, negatively affecting many other areas of cooperation. Targeted sanctions against a few individuals close to the Maduro administration, like those announced in July, are likely to be more effective and less harmful to the population.

With the Venezuelan government desperately in need of foreign culprits for the country’s economic woes, a U.S. oil embargo would provide the ideal excuse for Maduro

The sanctions announced by the U.S. government against Venezuela in August have already begun to complicate the South American country’s financial situation, but they are unlikely to lead to its ninth default since 1902. The new restrictions prohibit U.S.-American citizens and companies to trade new Venezuelan bonds, making it harder for PDVSA (Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A., the Venezuelan state-owned oil and natural gas company) to refinance its debt burden. Yet the sanctions fall short of a full embargo, which would have a far more profound effect on the Venezuelan economy, almost certainly causing social instability and severe product shortages until Caracas would find alternative buyers of the 700,000 barrels of oil it sells daily to the United States. What the sanctions do achieve, however, is further consolidation of Chinese and/or Russian influence in Venezuela.

All this explains why the region has been unable to influence events in Venezuela, and why Maduro can be expected to remain in power for now. In fact, the greatest threat to his rule does not come from the political opposition, but from the armed forces. Maduro’s capacity to hold on to power despite economic trouble can also be explained by the fact that decision-makers in Caracas operate according to a clear –and effective– set of principles.

Indeed, Maduro and his predecessor Hugo Chávez have long been aware of the fact that high-profile ruptures of democratic order –such as imprisoning all antagonistic politicians at once– risks mobilizing and unifying the domestic opposition as well as governments in the region. So, when the need to crack down on dissent or opposition arises, Maduro has opted for an incremental, two steps forward and one step back approach that has allowed him to effectively outfox the normative frameworks established to preserve democracy in Latin America.

For example, the decision in April to bar opposition leader Henrique Capriles from running for president in 2018 is consistent with this strategy. It was also on display when Venezuela’s Supreme Court usurped the functions of the democratically elected National Assembly. After an international uproar, fully expected by government officials, Maduro asked the courts, which he controls, to back off.

What many international observers overlooked, however, was that Maduro had still achieved his primary goal, as the back and forth left in place comprehensive new powers for Maduro to sign oil deals for Venezuela’s state-run oil company without approval by Congress. The President now has the autonomy to launch new joint ventures with foreign firms, or to sell the country’s oil fields, which contain the world’s largest proven reserves. It is a crucial tool in the regime’s increasingly desperate battle for survival. Last year, for example, the government pocketed half a billion dollars from the Russian state-run company Rosneft, which increased its stake in the Petromonagas joint venture.

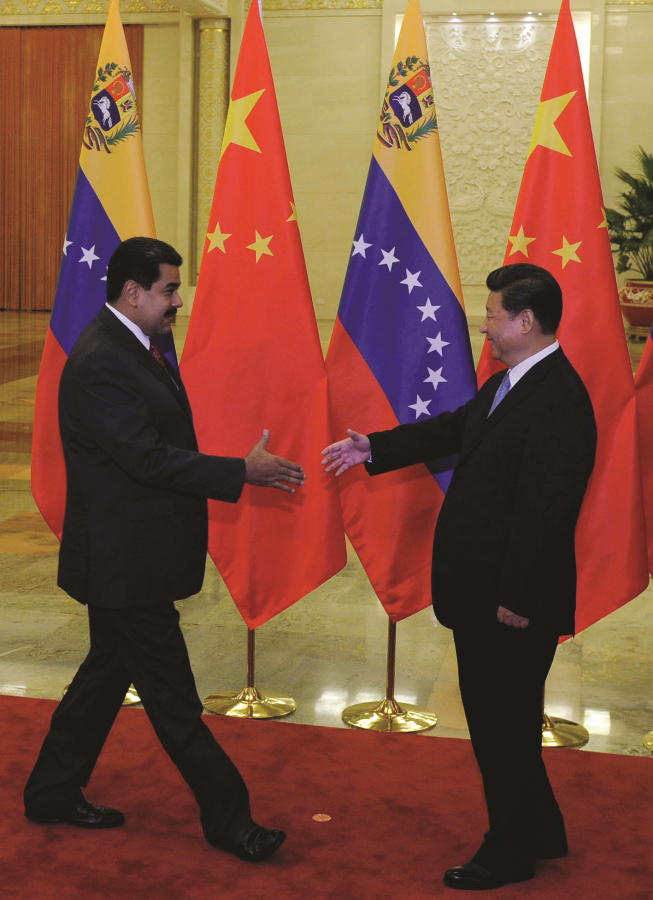

Chinese President Xi Jinping meets with Venezuela’s President Nicolas Maduro upon his arrival to Beijing before China’s huge military parade in September 2015. | AFP PHOTO / PARKER SONG

Chinese President Xi Jinping meets with Venezuela’s President Nicolas Maduro upon his arrival to Beijing before China’s huge military parade in September 2015. | AFP PHOTO / PARKER SONG

After barring Capriles from public office for 15 years, protests ensued. The government subsequently made a small concession and allowed regional elections to go ahead. This was not a sign that Maduro’s main concern is growing international pressure. Rather, it points to Maduro’s clear belief that holding free and fair elections would almost certainly lead to Chavismo’s defeat at the polls. That, in turn, would result in the prosecution of a sizeable number of current political and military leaders for involvement in drug trafficking, corruption or human rights abuses. Renewing Chavismo by temporarily allowing another party to take over is not an option.

Today, many international analysts suggest that the end of Chavismo will inevitably be the starting point of a process of economic and political recovery of the country. Yet not only is the end of Chavismo likely, but it is also an excessively optimistic view based on a simplistic assessment of a country that whose ailments are far more numerous and complex than Chavismo alone. This should not be understood as an implicit show of support for President Maduro’s continued hold on power. Quite to the contrary, it seems fairly obvious that any kind of recovery, both economic and political, can only be led by Maduro’s successor. In addition to the economic collapse, the current government is directly responsible for countless political prisoners and hundreds, probably thousands of people who have needlessly died as a result of the lack of even basic medicine in Venezuela’s public hospitals.

Yet overcoming Chavismo alone will only be the first step in a far longer and complicated process that requires changing not only how elites relate to the rest of society, but also how society as a whole views the role of the state in the economy. As any historian can point out, Venezuela’s deep problems –most of them related to the country’s obscene oil wealth and its economic dependence on it– precede the rise of Chávez, and there is little to suggest that any future, post-Chavismo government, can solve them easily. That explains why a surprising amount of Venezuelans wants Maduro to go, but many are surprisingly skeptical about whether the opposition will do a much better job.

Even if an anti-Chavista politician were to succeed Maduro, he or she would still depend on the support of Chavistas both on the bureaucratic and the political level

Paradoxically, however, even if an anti-Chavista politician were to succeed Maduro, he or she would still depend on the support of Chavistas both on the bureaucratic and the political level. Chávez and Maduro have merged state and party to such a degree that no neutral technocrats are left, and purging anybody who sympathized with Chávez or Maduro would leave the country entirely dysfunctional. That means that, should Maduro fall, a witch hunt must be avoided at all costs –actually, behind closed doors, the opposition admits that transition may involve giving a broad and generous amnesty– keeping most public employees in place.

Reducing human suffering across the country by delivering medicine, vaccines and food will not only limit refugee flows, but also help Brazil and Colombia manage the growing public health crises in their respective border regions

For the region, this means two things. First of all, Venezuela will be a long-term patient, and as such, foreign ministries in the region must adopt a long-term strategy when it comes to dealing with the country. This, however, could generate unforeseen tensions. Brazil, for example, will try to avoid any post-Chavismo government turning into a staunch U.S. ally, similar to Colombia, as this would increase U.S. influence in South America far more than Brasília would like.

Secondly, given that a meaningful dialogue between the government and opposition is highly unlikely at this point, regional governments should limit their goals to helping Venezuela deal with the humanitarian crisis. Brasília, Bogotá, Buenos Aires and other regional governments should therefore lead an international effort to put pressure on the Maduro government to allow the delivery of basic medicines to hospitals across the country. Addressing the humanitarian crisis is not only morally compelling, but remains very much in the regional governments’ national interests: the longer the problem festers, the greater the risk of civil strife in Venezuela, which could create instability on a regional scale. It will also worsen the refugee crisis, with up to 800,000 Venezuelans in Colombia5 and more than 20,000 in Brazil.

A survey conducted last year by Datincorp, a pollster based in Caracas, found that 57 percent of all Venezuelans said they want to leave the country, up from 49 percent in May 2015.6 While fixing a broken economy is a challenge, convincing the young and educated to come back in a few years will be harder still, with its politics chronically unstable and a well-organized and receptive diaspora in places like the United States and Argentina, many will never return. A brain drain is the worst possible scenario for an economy that is desperately trying to reduce its dependence on oil and diversify into other industries and services.

Reducing human suffering across the country by delivering medicine, vaccines and food will not only limit refugee flows, but also help Brazil and Colombia manage the growing public health crises in their respective border regions. For now, the Maduro government has rejected any kind of aid, as it would imply recognizing the gravity of the crisis. One way to deliver aid could to invest in so-called “parallel diplomacy,” and incentivize the establishment of channels of communications between Brazilian and Venezuelan armed forces as well as between the Church, who might receive and distribute humanitarian aid. Another option would be to deliver aid to Cuba, which could pass it on to Caracas.

Accepting humanitarian aid is tricky for any government, even authoritarian ones, because it is an obvious acknowledgment of severe economic policy failures (particularly in Venezuela’s case, as the crisis cannot be blamed on a bad harvest). And yet, convincing a country to accept humanitarian aid is far easier than successfully mediating between an authoritarian government and the opposition, which generates uneasiness about sovereignty. It is the least Brazil and the region can do after having greatly benefited from Venezuela’s bonanza for years and having let down its people.

Endnotes

- Ricardo Hausmann, “Venezuela’s Economic Collapse Owes a Debt to China,” Financial Times, (January 20, 2015), retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/

6f6436a2-a0ae-11e4-8ad8- 00144feab7de. - Marianna Parraga and Alexandra Ulmer, “Special Report: Vladimir’s Venezuela - Leveraging Loans to Caracas, Moscow Snaps Up Oil Assets,” Reuters, (August 11, 2017), retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/

article/us-venezuela-russia- oil-specialreport- idUSKBN1AR14U. - Thomas O’Donnell, “Russia Is Beating China to Venezuela’s Oil Fields,” Americas Quarterly, (January 2016), retrieved from http://www.americasquarterly.org/content/

russia-beating-china-venezuelas-oil-fields. - Moisés Naim, “Así Podría Salvar Trump a Maduro,” El Pais, (July 23, 2017), retrieved from

https://elpais.com/elpais/2017/07/22/opinion/1500736448_801513.html. - Manuel Rueda, “Venezuelan Refugees Strain Colombian Border Towns,” Americas Quarterly, (May 17, 2017) from http://www.americasquarterly.org/content/

venezuelans-seek-refuge-neighboring-countries. - Jim Wyss, “Almost 60 Percent of Venezuelans Say They Want Out,” Miami Herald, (September 9, 2016), retrieved from http://www.miamiherald.com/

news/nation-world/world/ americas/venezuela/ article100931647.html.