Events in the Middle East, and the wider region, continue to unfold at a dizzying pace. The war in Syria continues unabated. Russia has now intervened militarily to prop up the government of Bashar Assad. Iran is ramping up its military involvement in the conflict. In Iraq, the U.S.-trained army has collapsed, deep sectarian divisions remain, and the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) controls large swaths of both Iraqi and Syrian territory. Libya has fallen into anarchy. Slightly further afield, the Taliban are resurgent in Afghanistan, and President Obama has been forced to do a U-turn on his pledge to withdraw all U.S. military forces –except for a residual force of 1,000 troops to protect the American embassy in Kabul– from that country by the end of his term in January 2017. The spillover from the conflicts in Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, and Libya is washing over Europe in the form of a massive stampede of refugees. In short, regional turmoil is at a fever pitch, and it seems that Washington’s Middle East policy has reached a dead end.

What explains the failure of America’s policy in the region, and where should the U.S. go from here? My argument is that the regional turmoil fundamentally stems from the George W. Bush administration’s disastrous decision to invade Iraq in March 2003. Compounding the problem, President Barack Obama’s policy has been contradictory and ambivalent. President Obama rightly concluded that the United States needs to extricate itself from the two wars started by his predecessor. He has resisted calls from his critics to step-up U.S. military involvement in the Syrian civil war, and has tightly limited –“no boots on the ground”– the American contribution to the campaign against the so-called Islamic State. At the same time, although his instincts have been to wind down the American military role in the region, when pressed by hard-liners in the U.S. foreign policy establishment, he has often lacked the courage of his convictions. For example, the 2011 Libya intervention, the 2009 “surge” and recent U-turn in Afghanistan, and the reinsertion of U.S. military forces into Iraq in response to the rise of ISIL. When it comes to strategy, there is a good deal of evidence that Mr. Obama favors what is called “offshore balancing,” which will be explained in more detail below. However, his inability to hold firm to his preferences in the face of pressure from the U.S. foreign policy establishment means that the United States has probably has lost its best chance to come to terms with the intractability of the Middle East’s conflicts, and the inevitable failure of U.S. attempts to stabilize, and/or democratize the region.

By invading Iraq, in one fell swoop the U.S. both created a power vacuum in Bagdad that was filled by Iran, and sparked the Sunni/Shia civil war

The George W. Bush Administration’s March 2003 invasion of Iraq unhinged an already volatile region. The administration went to war to attain regime change in Baghdad, and to trigger a benign domino effect that would democratize the Middle East. The administration’s policy was shaped by the neo-conservative mantra, echoed by liberal hawks, that a muscular U.S. foreign policy –based on military power, and the promotion abroad of American ideology– could transform the Middle East. It was the vision of regime change, the export of democracy, and Washington’s own hubris-drenched imperial ambitions that plunged the United States into the geopolitical cul-de-sac in the region, in which it now finds itself. The Bush administration’s Iraq goals were pipe dreams. Any policymaker with a sense of history –not least the Vietnam debacle– should have known that American attempts to impose democracy at the point of a gun invariably end in failure.

Iraq was not about 9/11 –there was zero connection between Saddam Hussein and al-Qaeda– and it was not about “Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMDs),” of which there were none. We know –and it ought to have been known at the time to Bush administration officials– that Washington’s articulated rationales for the war were false. Had the Bush administration allowed the United Nations weapons inspectors to complete their work, the fact that Iraq had no WMD’s would have become obvious. Similarly, notwithstanding the administration’s claims to the contrary, Saddam Hussein posed no threat to U.S. allies and client states in the region. Iraq had been weakened by years of sanctions, and was effectively hemmed in by American military power. The truth, as the so-called Downing Street memos make clear, is that at least a year before the invasion the Bush administration had decided to use military force to overthrow Saddam Hussein. As British intelligence warned London in July 2002, “Bush wanted to remove Saddam, through military action, justified by the conjunction of terrorism and WMD.” The British also noted that the administration’s “case was thin. Saddam was not threatening his neighbors and his WMD capability was less than that of Libya, North Korea, or Iran.”

There were plenty of warnings –which the Bush administration willfully brushed aside– that an invasion of Iraq would have catastrophic consequences. For example, before the war an independent working group co-sponsored by the Council on Foreign Relations and Rice University’s James A. Baker Institute for Public Policy warned that, “There should be no illusions that the reconstruction of Iraq will be anything but difficult, confusing, and dangerous for everyone involved.” The working group also warned that “The removal of Saddam... will not be the silver bullet that stabilizes” the Middle East.

In the same vein, a February 2003 study written by two U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute analysts debunked the administration’s notion that American troops would be greeted as liberators by the Iraqis. Rather, the War College analysts stated:

Most Iraqis and most other Arabs will probably assume that the United States intervened in Iraq for its own reasons and not to liberate the population. Long-term gratitude is unlikely and suspicion of U.S. motives will increase as the occupation continues. A force initially viewed as liberators can rapidly be relegated to the status of invaders should an unwelcome occupation continue for a prolonged period of time.

The authors highlighted the probability that U.S. occupation forces would find themselves facing guerilla and terrorist attacks - or even a large-scale insurrection. The report also stressed that “the establishment of democracy or even some sort of rough pluralism in Iraq, where it has never really existed previously, will be a staggering challenge for any occupation force seeking to govern in a post-Saddam era.” Ethnic and sectarian tensions, the authors noted, not only would constitute a formidable obstacle to Iraq’s democratization, but also could lead to the break-up of a post-Saddam Iraq. The authors’ –prophetic– bottom line was that, “The possibility of the United States winning the war and losing the peace in Iraq is real and serious.”

The U.S. intelligence community also counseled the administration to refrain from going to war, and forecast that if did invade, the United States would face a “messy aftermath in Iraq.” The intelligence community also believed that a postwar Iraq “would not provide fertile ground for democracy; would witness a struggle for power between Sunnis and Shiites; and would require ‘a Marshall Plan-type effort’ to rebuild the nation’s economy.” Collectively, these prewar analyses were prescient. But an administration driven by a “faith based” belief in the efficacy of American power, and blinkered by a messianic foreign policy ideology, ignored the warning signs.

By invading Iraq, in one fell swoop the U.S. both created a power vacuum in Bagdad that was filled by Iran, and sparked the Sunni/Shia civil war. The Bush administration midwifed the birth of ISIL. The U.S. not only toppled Saddam Hussein. It also destroyed the institutions of the Iraqi state, and upended the sectarian political balance, which from the end of World War I (the beginning of the modern Iraqi state) had been tilted in favor of the minority Sunnis. This destabilization created the opening for a bitter internecine conflict between Iraq’s Shiite and Sunni populations. By 2007 the conflict had become so severe that the Bush administration decided to “surge” additional troops to Iraq to end the strife.

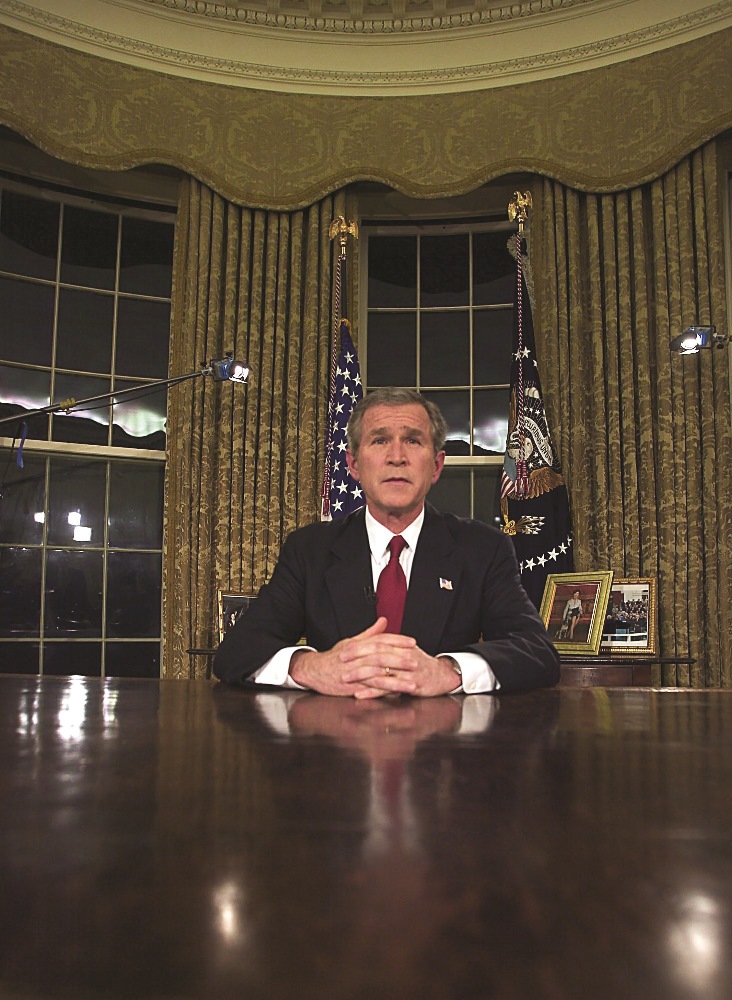

Then, U.S. President George W. Bush addressed the nation late 19 March 2003 in Washington, DC and announced he had launched war against Iraq. | AFP PHOTO / LUKE FRAZZA

Then, U.S. President George W. Bush addressed the nation late 19 March 2003 in Washington, DC and announced he had launched war against Iraq. | AFP PHOTO / LUKE FRAZZA

To be sure, the surge did reduce sectarian strife in Iraq. By no means, however, did it end it. More important, notwithstanding the assertions of leading Bush administration officials that the surge was a “success,” it failed to achieve the administration’s overriding objective. This, as President George W. Bush stated, was to buy time to foster political reconciliation between Iraq’s Sunni’s and Shiite populations. This reconciliation never happened. Iraq remained polarized and unstable. Under the leadership of then Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki, the Shiites consolidated their power internally, and aligned externally with their natural ally, predominately Shiite Iran. Consequently, Iraq’s Sunni population remained alienated politically from the Shiite-dominated regime in Baghdad, and resentful of their displacement from power. It was disaffected Sunni’s –including many former officers in Saddam Hussein’s army– who formed the backbone of ISIL.

When ISIL burst on the scene seemingly out of nowhere, the architects and executors of the George W. Bush Administration saw –and seized– and opportunity to revise history. There is a historical parallel. After their defeat in 1918, Germany’s military leaders denied that the Allies had prevailed on the battlefield. Rather, they said, the German Army had been “stabbed in the back” by disloyal elements on the home front. In a similar vein, Bush administration apologists claimed that by fumbling away the American “victory” purportedly won by the 2007 surge, the Obama administration bore sole responsibility for the emergence of ISIL because, allegedly due to its precipitous withdrawal of U.S. combat forces from Iraq.

By raising the hopes of the anti-Assad forces that the U.S. would intervene on their behalf, the Obama administration caused an intensification of the Syrian civil war

This argument was disingenuous. It was the 2003 invasion, and subsequent occupation, of Iraq that created the conditions for ISIL’s emergence. Indeed, ISIL’s rise demonstrated that Iraqi Sunnis were unwilling either to accept the diminishment of the political power they wielded under Saddam Hussein, or to be ruled by a Shia regime in Baghdad. Even more, the narrative constructed by Bush administration apologists overlooked two crucial facts. First, U.S. forces were withdrawn from Iraq in 2011 pursuant to the terms of a 2008 status of forces agreement that the Bush administration itself had negotiated with the Iraq regime. Second, Mr. Obama was prepared to keep a residual force of American combat troops in Iraq for several years. However, Washington was unable to reach agreement with Baghdad to this effect, because the Maliki regime wanted the Americans out of Iraq. Simply put, the claim of Bush administration apologists that fruits of its “victory” were thrown away by the Obama administration is nonsense.

ISIL’s summer 2014 seizure of large swaths of Syrian and Iraqi territory, and its grisly murders of two U.S. citizens, had two effects. First, it served to thrust Iraq back onto center stage of the Washington foreign policy debate. Second, it underscored the linkages between the situation in Iraq and the Syrian civil war. Neoconservatives and liberal hawks alike began beating the drums for a significant ramping up of U.S. military involvement in both Iraq and Syria. Falling back on the time-tested tactic of threat inflation, neocons, Republican politicians, and key members of Mr. Obama’s own foreign policy team tried to steamroll him into intervening in Syria’s civil war, and militarily re-engaging in Iraq. Hawkish elements in the U.S. foreign policy establishment –including Secretary of State John Kerry and then-Defense Secretary Chuck Hegel– deliberately and cynically stoked war fever by luridly and hyperbolically over-hyping the menace posed by ISIL, which some of them described as an “existential threat” to the United States. To believe otherwise, they said, was delusional.

Apparently, then, many U.S. Middle East experts must have been deluded, because few of them bought into the claim that ISIL posed any kind of imminent threat to the U.S. As the New York Times reported on 10 September 2014, “American intelligence agencies have concluded that it [ISIL] poses no immediate threat to the United States.” Speaking to the nation, President Obama conceded that the U.S. has “not yet detected specific plotting against our homeland.” The reason ISIL was not an “existential” threat to the U.S. ought to have been apparent to anyone with an ounce of strategic sense. ISIL cannot focus on the United States because it is surrounded by hostile forces, and it must focus on its “near” enemies in order to consolidate its grip on the territory constituting its self-declared “state.”

With respect to Syria and Iraq, Mr. Obama’s report card is mixed. On the plus side, at least until now, he has successfully resisted the calls of U.S. hawks for direct American military intervention in Syria’s civil war. However, in the wake of Russia’s military intervention in Syria, the numerous residual Cold Warriors in the U.S. foreign policy establishment have renewed their calls for Washington to assert itself militarily in Syria. Similarly, despite pressures from leading figures in the American military –notably the recently retired Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Martine Dempsey– for a stepped up American role in the fighting in Iraq, Mr. Obama has carefully kept U.S. troops out of harm’s way. American forces are confined to training, and providing intelligence and logistic support to the Iraqi military. Rightly eschewing calls for American boots on the ground, Mr. Obama decided that the United States would focus on supporting the Iraqis, and rely on air power to strike ISIL.

On the negative side, in August 2014 Mr. Obama unwisely declared that Bashar Assad had to “go.” This was a mistake on several levels. First, it overlooked the fact that U.S. choices in the Middle East are not between good and bad –democracy and tyranny– but rather between awful and worse. The Obama administration apparently learned nothing from its reckless decision –in the midst of the so-called Arab Spring– to pull the rug from underneath the former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak. Authoritarian rulers may not be good but they are preferable to power vacuums that will create space that can be occupied by jihadists and radical Islamists. Second, by raising the hopes of the anti-Assad forces that the U.S. would intervene on their behalf, the Obama administration caused an intensification of the Syrian civil war. As former State Department official Anne-Marie Slaughter said, given the Obama administration’s reluctance to use U.S. military power to remove Assad, Washington erred in issuing an ultimatum that he had to give up power. “If we’re going to get people’s hopes up when we’re not willing to do more,” she said, “we need to be honest about that and maybe it’s better to remain silent.” Third, by demanding Assad’s ouster, the Obama administration limited its options to achieve a diplomatic settlement in Syria. As Bookings Institution scholar Bruce Jones put it, “If you call for Assad to go, you dramatically drive up the obstacles to a political settlement. If you’re not insisting on him leaving there are more options. If you say Assad must go as the outcome of a settlement he has the existential need to stop that settlement.” It was a mistake to lay down a marker –or draw a “red line”– that Washington was not prepared to enforce.

Where should the U.S. go from here? The first thing that is needed is a realistic appraisal of the situation. The U.S. has no good options in Iraq and Syria. Air power alone can neither “defeat” nor “degrade” ISIL. Given the Mr. Obama’s decision –a correct one– not to commit American forces to land warfare in Syria and Iraq, Washington has been forced to rely on regional proxies –“moderate” anti-Assad Syrian rebels, the Iraqi army, and Iraqi and Syrian Kurds (YPG)– to provide the needed ground forces fight ISIL. The efficacy of this strategy, however, is doubtful. Most fundamentally because as Financial Times correspondent Roula Khalaf has observed, true moderates among the Syrian rebels are few and far between. Indeed, to the extent these “moderates” exist at all, it is primarily in the febrile imaginations of foreign policy mavens in Washington. Certainly, there are no effective Syrian moderates fighting in that nation’s civil war. The recent humiliating failure of U.S. backed Syrian “moderate” forces –trained by the United States at the cost of $500 million– is dramatic proof. Splintered among various factions, the Syrian rebels have no unified command or strategy. It is the most extreme among them who have been the most successful militarily, and they are interested primarily in fighting Syrian President Bashar Assad –not ISIL. That is to say, their objectives do not coincide with Washington’s.

The Obama administration has pinned its hopes in Iraq on the notion that the supposedly “more inclusive” government of the new prime minister, Haider Abadi will be able to rebuild Iraq’s military capabilities

The notion that the U.S. can call into existence credible Iraqi military forces is equally far-fetched. The Iraqi army –rebuilt at a cost to the U.S. of $25 billion– collapsed in the face of an ISIL onslaught in 2014. Key cities –including Mosul, Ramadi, Tikrit, and Falluja– were overrun by IS forces. To date, the Iraqis have been unable to retake these cities. Moreover, such military successes as the Baghdad regime has had have been won by Iraqi Kurdish Peshmerga forces, and by Shiite militias –which are closely linked to Iran– and not by regular Iraqi army units. The Obama administration has pinned its hopes in Iraq on the notion that the supposedly “more inclusive” government of the new prime minister, Haider Abadi will be able to rebuild Iraq’s military capabilities. There is no reason to believe this will happen, however, because the Sunni/Shia divide is too deep, and the foundations on which a unitary Iraqi state can be built have been shattered.

In contrast to his actions, it is evident that Mr. Obama’s instincts are to extricate the United States from the quagmires of Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan. But his opponents have kept up the pressure on him to expand the American role in these conflicts. He has given into that pressure even if only half-heartedly. He thus bears a good deal of the responsibility for the fact that he has not been able to stay the course and end the American military involvement in these wars –something that was supposed to have been the foreign policy capstone of his administration. Mr. Obama’s summer 2014 statement, which lacked a strategy to deal with ISIL, gave his opponents and opening, which they seized to fuel the interventionist fire. The irony is that Obama, in fact, did –and does– have a strategy for dealing with ISIL (and Afghanistan). That strategy is what security studies scholars call “offshore balancing.” In a nutshell, as an offshore balancer the United States would stay out of the Syrian and Iraqi –and Afghan– conflicts militarily, and shift the responsibility to regional powers for containing, or rolling back, ISIL and the Taliban.

The risks of deeper U.S. involvement in these conflicts are clear. Obama’s policy will further entangle the United States in the complex politics and rivalries of a region that American policymakers –even (or especially) the so-called experts– can neither understand nor control. The U.S. will be sucked deeper into a vortex of geopolitical, ethnic, and religious conflicts. Geopolitically, the crisis in Iraq and Syria reflects the competition for regional influence between Iran and Saudi Arabia –not to mention Russia’s interest in ensuring the survival of the Assad regime. Moreover, the Arab states upon which the Obama strategy depends, are divided between those that support political Islam and the jihadists (openly or tacitly), and those that don’t. Obama’s policy will put the United States squarely in the middle of these multi-layered regional rivalries.

Offshore balancing is a far better way of dealing with ISIL than the Obama policy –or the even more hardline policies advocated by his critics. Rather than being an existential threat to the United States, ISIL is itself existentially threatened. No great, or regional, power supports it. All of the major regional powers –Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Syria– and Russia want to see ISIL contained or defeated. However, the regional powers have competing as well as parallel interests, and each wants to pursue its own individual political agenda while doing as little as possible to stop ISIL. Each prefers to buck pass to the United States –and secondarily to the other regional powers– to do the heavy lifting of confronting ISIL. For these reasons, the U.S. orchestrated coalition against ISIL is fragile.

This is unsurprising. The Middle East being what it is, America’s allies are at best allies of a kind –the kind that play both ends against the middle. For example, earlier this year Turkey finally agreed to allow the United States to use the Incirlik airbase to conduct strikes against ISIL, and also agreed to commit its own military forces to the campaign against ISIL. However, it is evident that Turkey’s strategic priority is not to attack IS. Rather, Ankara’s overriding objectives are to force Assad from power, and to strike at the predominately Kurdish PKK which has waged a long-running, intermittent insurgency against the Turkish government. In addition to attacking the PKK, Turkish aircraft also have bombed the Syrian Kurdish forces (YPG) which have been the main U.S. proxy forces battling ISIL in Syria. Similarly, Saudi Arabia is a feckless ally. The Saudi’s have their own ties to the jihadists –whom they view as a useful in waging a proxy war against Iran. Moreover, Saudi Arabia’s Wahhabi brand of Islam is a powerful motivator for anti-Western jihadist fighters in Syria (and elsewhere in the region).

Air power alone can neither "defeat" nor "degrade" ISIL.

As long as they believe that the United States will take care of ISIL, the regional powers have every incentive to free-ride and minimize their own commitments, costs, and risks, while pursuing their own agendas. The Obama Administration policy thus had created a strategic version of moral hazard. After all, ISIL is a threat to its neighbors, not to the United States. Washington’s policy should be to compel the regional powers to step up to the plate, and take full responsibility for defeating or containing ISIL. When they realize that America is not going to ride to their rescue, the regional powers will have no other choice but to do so because their own survival will be on the line. A similar dynamic is at play in Afghanistan, where Russia and China fear a northward Islamic extremist thrust that will menace their respective interests in Central Asia. The American (and NATO) military presence in Afghanistan means that Moscow and Beijing are able to stand back while the U.S. shields them from the dangers of radical Islam.

The wisest American strategy is to pivot away from the Middle East. The burdens of fighting ISIL –and the Taliban– should be borne by those whose security is most at risk. This includes not only Turkey, but also Iran and Russia. Members of the U.S. foreign policy establishment who are aghast at Russia’s intervention in Syria are suffering from a bad case of strategic myopia. Instead of fearing Russian, or Iranian, involvement in this conflict, American policymakers should welcome it. Far better for them –rather than the United States– to pay the cost in blood and money exacted by the thankless, futile, and impossible task of attempting to stabilize the Middle East.

Barack Obama was on the way to becoming America’s first offshore balancing president, and was –more or less– successfully pursuing that strategy. He moved to extricate the U.S. from futile wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Obama placed America’s Middle East conflicts in a wider strategic perspective. Against the background of China’s rapid rise, and America’s own fiscal and economic crisis, he rightly asked what is the sense of borrowing money from China to fight in the Middle East at a time when U.S. power is in relative decline. He understood that America’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan –and a potential war in Syria– would have the same effect of weakening U.S. power that the Boer War had for Britain at the beginning of the 20thcentury. Far more than the American foreign policy establishment, Mr. Obama seemed to understand the tectonic geopolitical and economic shifts that have brought the unipolar era of American dominance to an end. Regrettably, however, Mr. Obama has lacked the fortitude to stick to his strategic guns. In his remaining time in office, it is likely –though not certain– that he will follow his new course of limited American engagement in Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan. His successor, however –whether former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton or one of the crop of Republicans seeking that party’s presidential nomination– will be far more hawkish. By not liquidating these costly and unwinnable conflicts during his term, Mr. Obama has made it likely that his successor will plunge the U.S. more deeply in the region’s geopolitical morass.