The March 30, 2014 local elections epitomized the fiercest battle fought in Turkish political history between the government and an anti-government coalition that included a range of legitimate and illegitimate actors from opposition parties to the furtive agents of a phantom “parallel structure” embedded in vital branches of Turkish bureaucracy. A series of momentous events that unfolded between mid-2013 and the eve of Election Day practically turned the March 30 local elections into general elections, as well as a vote of confidence for the AK Party rule and the leadership of Prime Minister Tayyip Erdoğan. The Gezi Park protests, the military coup in Egypt, the increasing disconnect and erosion of trust between the West and Prime Minister Erdoğan, and the December 17 corruption allegations influenced the psyche of leaders, politicians and constituents on both aisles of the political spectrum to the extent that each waged an existential war against the other. By doing so, as will be elaborated in this paper, they appear to have set the wheels in motion—albeit inadvertently—for the AK Party’s electoral victory and contributed to its metamorphosis into a dominant party, the emergence of a “New Turkey,” and unprecedented polarization on all levels of Turkish society.

The December 17 raid on the homes of three cabinet ministers’ sons and a government bank executive on money laundering and bribery allegations not only increased the political tension and polarization in the days leading up to the elections, but also transformed the local elections into a referendum on the place and position of Prime Minister Erdoğan in politics. The AK Party leadership reacted similarly by denying the charges and shifting the blame to a conspiracy to remove Erdoğan, implemented by a “parallel structure” deeply embedded in key state apparatuses, such as the judiciary and police. In his campaign speeches, Erdoğan accused the self-exiled cleric Fethullah Gülen, who resides in Pennsylvania, United States, of contesting his rule through the agents of his religious order (known as cemaat or Hizmet movement in Turkish), who allegedly penetrated vital branches of the Turkish state. A clash between the ruling party and the Gülen movement had already surfaced on two occasions: first, a secret meeting between the Turkish intelligence agency and members of the PKK terrorist organization in 2012 was leaked through Gülenist channels; and second, the government retaliated by deciding to close private tutoring facilities in Turkey, which are a major source of funding for the Gülen movement. Furthermore, Gülen had criticized the AK Party government in a number of instances, such as the handling of the tragic Mavi Marmara raid by Israeli commandos in 2010, the Kurdish question and the Peace Initiative, and the Gezi Park events of last year.

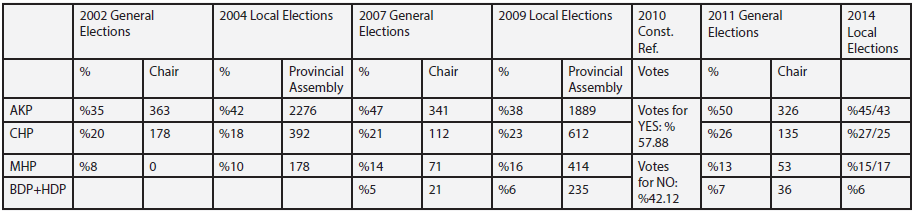

Electoral victories since 2002 have elevated the AK Party to the position of the “dominant party” in Turkish politics

As the elections drew near, attacks against the AK Party leadership increased. The illegal tapping of high government officials’ phones exposed shocking revelations regarding the extent of the government’s seeming involvement in corruption and its interference with fundamental freedoms of expression, press, and enterprise, as well as the rule of law. The AK Party government responded by attempting to consolidate its control over the police and judiciary, suspending or relocating more than 5000 law enforcement officers, as well as the prosecutors who authorized the raids. With the release of more illegal recordings, including deliberations between high-level government officials, the military, and intelligence officers concerning “clandestine operations” in territories adjacent to the Turkish border, the AK Party administration reacted more severely by banning access to Twitter and YouTube. On the other hand, opposition parties based their campaigns on these revelations to taint the legitimacy of the ruling party in their constituents’ eyes. The result was the strengthening of the AK Party’s support, its post-election vow to design a new Turkey in its image, and increased polarization.

The March 30 local elections were therefore the most tense and polarized elections in contemporary Turkish political history vis-à-vis discourse, rhetoric, and the attitude of political leaders toward one another. Nevertheless, the AK Party and, more specifically, Prime Minister Erdoğan have come out as the decisive winners. Fethullah Gülen and his movement have lost. The opposition parties, especially the Republican People’s Party (CHP), on the other hand, did not receive the percentage of votes that they had projected before the elections. This was the third consecutive local election victory for the AK Party—similar to its third general election triumph on June 12, 2011. Although the AK Party appears to have lost almost two million popular votes since 2011, the results reaffirmed Erdoğan’s advent as a strong candidate for the presidential elections and the AK Party for the 2015 general elections. The election results consolidated the electoral hegemony of the AK Party, fortified its rule and governance without strong opposition, increased its power and legitimacy, and maintained the strong leadership position of Erdoğan within his party, as well as in Turkey. It is likely that the AK Party will remain in power until at least 2019. Concomitantly, the “New Turkey” and “2023 Vision,” upon which Erdoğan has structured his electoral strategy, will hail as an achievable reality, rather than a utopia, at a time when our globalizing word is in turmoil and severe crisis. Yet, the New Turkey appears to be a highly polarized and fragmented society along secular, religious and ethnic lines, with a strong leader and weak opposition. This leaves us with a picture that points to risks and uncertainties in the areas of democracy, living together in diversity, and active foreign policy.

Electoral Hegemony and Dominant Party

The AK Party’s rise to the top started with the November 3, 2002 national elections. Eleven years on, the AK Party clings to power ever more resolutely. The consecutive electoral successes of the AK Party since 2002 continue to generate “a political earthquake-like impact” on Turkish politics and modernity. In 2002, the three governing parties that formed a coalition government after the 1999 national election, as well as the two opposition parties, failed to pass the 10 percent national threshold. They were thrown out of parliament and found themselves as the complete losers of the election. The sole winner of the election was the newly created AK Party. By receiving 34.2 percent of the popular vote and with the aid of the undemocratic 10 percent national threshold, the party gained 66 percent of the seats in parliament (363 out of 550 seats) and constituted a strong majority government.1 On July 22, 2007, the election results caused another political earthquake. This time, the ruling AK Party achieved a landslide victory, receiving 47 percent of the vote. This was the largest share for a single party since the elections of 1957 and the second time since 1954 that an incumbent party significantly increased its votes in a subsequent election. Despite a number of serious attempts undertaken by the military, judiciary, opposition parties, the media, and civil society organizations to confront the AK Party’s mode of governance, the July 22, 2007 general elections not only fortified the power of the AK Party government, but also eliminated all attempts to prevent Abdullah Gül from becoming president. Soon after the election, Abdullah Gül became the new president of Turkey.

One of the indicators for the dominant party position of the AK Party is its ability to use the “2023 Vision” as an electoral strategy in a convincing way

A similar electoral victory occurred during the June 12, 2011 general elections; again, with earthquake-like results, the AK Party gained 50 percent of the public’s support in a landslide electoral victory. Moreover, before its third electoral victory in 2011, the AK Party participated in two consecutive municipal elections in March 2004 and March 2009. In both elections, despite the decline of its votes from 42 percent in the 2004 elections to 38.8 percent in March 2009, the AK Party won most of the provincial and greater city municipalities. Furthermore, “the opposition gained little and was divided across many modest to smaller size parties,” and “no single opposition party…gathered the electoral momentum” to present itself as a strong candidate to end the AK Party majority government. The AK Party won its third local election victory in 2014 by increasing its votes up to 43-45 percent. One could add the 2010 constitutional referendum, in which the AK Party had campaigned for the “Yes” vote, to this list as it resulted in 57.88 percent approval.

The success of the AK Party in these seven consecutive elections has been so strong that, as I have suggested elsewhere, it brought about two significant developments in Turkish politics.2

First, the fact that no party in Turkey’s legislative history has achieved electoral results even close to those of the AK Party has yielded the so-called “electoral hegemony” of the party. This not only means that the AK Party will most likely win the coming presidential (August 10, 2014 ) and general elections (June 2015), but also that even the supporters of the opposition do not believe that their parties will win the elections and govern Turkey. The concept of electoral hegemony explains the increasing gap between the incumbent party and opposition parties in terms of their capacity to win elections and govern Turkey. It also sheds light on why such terms as elections, the ballot box, and votes are taken very seriously by the AK Party.

As the 2002, 2004, 2007, 2009, 2011 and 2014 general and municipal election results indicate, as well as the 2010 referendum, the dominance of the AK Party in the electoral process constitutes a kind of electoral hegemony in which the party acts and governs Turkey without a strong opposition.

Moreover, electoral hegemony allows for the continuing growth of the AK Party’s and Prime Minister Erdoğan’s dominance in the political arena and it legitimizes, at least in the eyes of a large portion of the electorate, the association of democracy with the ballot box. Elections for the AK Party go beyond simply being the determinant of who governs Turkey. Since 2002, they have been used not only as a functional vehicle to gain legitimacy, but more importantly, they have contributed immensely to the consolidation and fortification of Erdoğan’s and the AK Party’s power. This has allowed the party to become a “hegemonic governing force,” shaping and reshaping not only politics and democracy but also modernity. In this sense, the concept of electoral hegemony refers to a situation in which the dominance of one party in the electoral process becomes so strong that its power exceeds simply being a strong majority government, it becomes hegemonic over society at large, and other parties and their supporters have no convincing ability to win elections.

Second, as a result of its electoral hegemony, consecutive electoral victories since 2002 have elevated the AK Party to the position of the “dominant party” in Turkish politics.3 Consecutive electoral victories have created a new situation in Turkish politics where, similar to the examples of the Liberal Democrats in Italy and the Social Democrats in Sweden, the AK Party has established a “cycle of dominance” by defeating its opponents, expanding its core social support, enlarging its zone of governance both nationally and locally, strengthening its class, sector, and identity-based societal alliances, and consolidating its constituency. A dominant party has both electoral and governing dominance in a recursive fashion; outdistances its opponents in terms of the extent of its popular/electoral support; creates a societal and global perception that its opponents are weak and unlikely to win elections; and, rather than uncertainty, elections under the existence of a dominant party involve certainty to a large extent with respect to the winner.4 Furthermore, the comparative data show that a party becomes dominant after its third term victory and governing party position.

The AK Party meets all of these benchmarks and it would not be an exaggeration to suggest that its electoral hegemony since 2002 has paved the way to its dominant party position in Turkish politics. Based on its past electoral triumphs, one can expect the AK Party to maintain this trend for the near-future. The outcome of the March 30 local elections, in which the AK Party acquired the power to govern 71 percent of Turkey on a local scale, fortifies and reinforces its dominant party position. It also signals that both the new president, either Erdoğan or Gül, and the new prime minister are likely to hail from within the AK Party in the 2014 presidential and 2015 general elections. This also suggests that Turkey will most likely be governed by the AK Party on both levels until at least 2019. Even if the existing power configuration changes among the opposition parties, the opposition will remain weak and the gap between the incumbent party and opposition parties will remain wide.

A number of conclusions can be advanced at this point:

(a) Unlike the Turkish party system of the 1990s, which was shaped by instability, uncertainty and weak coalition governments due to a high-level of volatility, fragmentation and polarization, the AK Party experience since 2002 has given rise to dominant party rule, strong majority governments, less volatility, and certainty based on consistent electoral victories. This has allowed the government to enact laws, make decisions, and implement policies which it saw as necessary not only to govern Turkey effectively, but also to initiate societal mobilization, leading to an enlargement and strengthening of its alliances and links with society.

(b) At a time when there are severe global challenges and crises in economy, security, food and water resources, as well as energy and climate. These create grave zones of instability. As most societies face uncertainty and ambiguity, the AK Party’s 2023 vision and roadmap appears neither utopian nor unachievable. In fact, one of the indicators for the dominant party position of the AK Party is its ability to use the “2023 Vision” as an electoral strategy in a convincing way. This vision will be used in the upcoming presidential and general elections, as well as in debates about whether Turkey should have a semi-presidential system with a strong president in order to achieve sustainable economic growth, increase its per capita income, and overcome the “middle income trap” to become one of the top ten economies of the world.

(c) Unlike the dominant party examples of Japan, Sweden, and Italy, in Turkish politics, the dominant party position of the AK Party operates with an extremely strong leader: Prime Minister Erdoğan. The AK Party rule in Turkey since 2002 has involved “dominant party + dominant leader formula,” which has functioned effectively thus far and will continue to do so after the March 30 local elections. What is called the “Erdoğan factor,” which includes strong and effective leadership as well as successful political strategy, played a crucial role both in the transformation of the AK Party into a dominant party through electoral hegemony and the ability of the party to differentiate itself from its opponents. Objectively speaking, none of the opposition parties have had a leader like Erdoğan since 2002.

There is in fact a name and a sociology to describe the AK Party’s constant victory, as well as the dialectic between the AK Party and the transformation: The New Turkey

(d) Lastly, the ability of the AK Party to create a strong circle of dominance, as corroborated by many, has stemmed to a large extent from its successful management and governance of Turkey’s transformation process, which has been ongoing for the last two decades. The AK Party’s rule and electoral hegemony are embedded in Turkey’s transformation. While Turkey’s transformation created the possibility for the party to emerge and win the 2002 elections, the party has effectively widened and deepened the transformation process through its successful domestic and foreign policies. The transformation is a multi-dimensional and multi-actor process, felt in each and every sphere of societal relations, ranging from the economy to culture, domestic politics to foreign policy, local to regional and global engagements. The process has also made Turkey more global, more urban and even, in many areas, more European despite the existing stalemate in Turkish-EU relations. It is a complex process involving potential and risks, which requires effective and convincing governance. Unlike the opposition parties, the AK Party since 2002 has been able to respond to the transformation effectively and the more it does so, the more it enlarges its societal support and alliances. Hence, while the transformation led to the AK Party’s electoral hegemony and dominant party position, the dominant party is also consolidating the transformation, that is, “AK Party rule: hegemony through transformation.”5

Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan greets his Justice and Development Party supporters during an election meeting. | AA / Abdülhamid Hoşbaş

Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan greets his Justice and Development Party supporters during an election meeting. | AA / Abdülhamid Hoşbaş

The New Turkey

There is in fact a name and a sociology to describe the AK Party’s constant victory, as well as the dialectic between the AK Party and the transformation: The New Turkey. The transformation is creating a “New Turkey” as an emerging reality. As Erdoğan has put it after the elections, “What has become clear after March 30 is that the New Turkey has won and has come closer to its completion.” The New Turkey entails a new state, a new historic block that includes a new military and judiciary, an emerging and indigenous group of intellectuals, a new stratification with a growing middle class of creative and active communities, and highly urbanized, globalized, Europeanized and dynamic social relations. It is a post-tutelage Turkey in which the civilian government is stronger than the military and the judiciary. The New Turkey is also a post-secular polity where religion is more visible, active, and established, and a post-modern society that consists of new class and identity dynamics. Yet, as will be further elaborated in the next section, the New Turkey is also more polarized and fragmented.

The most critical and pressing problem is the ongoing and unprecedented level of polarization in the political sociology of the country

First, the September 12, 2010 constitutional referendum, and, most importantly, the 2011 general elections ended the tutelary power of military to a large extent. After that, Turkey—in fact, the New Turkey—entered a post-military tutelage era, where the AK Party’s dominant party position became more consolidated. After the March 30 elections, with Erdoğan’s and his party’s uncontested victory vis-à-vis the Gülen Hizmet movement and its alleged “parallel state” in the judiciary and police, the AK Party acquired the chance and capacity to reshape the judiciary in order to eliminate what it considers to be tutelary power mechanisms. In that sense, the March 30 elections have made it possible for the AK Party to complete the transformation of the state and create a “new historic bloc” with a new governing, economic, and intellectual elite. The New Turkey, the political outcome of the AK Party’s electoral victory in Erdoğan’s words, is on its way towards completion.

We are in the process of the “making of the New Turkey” politically, economically, and culturally. The AK Party, with its electoral hegemony and dominant party position, is the main political actor in the process of making the New Turkey, while the new middle class functions as the main economic actor and the new media and think tanks contribute to this process intellectually, and by attempting to manufacture the necessary societal consent and perception for it. Interestingly, in his book, The Making of Modern Turkey (1982), Feroz Ahmad6 has a chapter called “New Turkey,” where he analyzes the process of radical transformation that Turkey underwent after the War of Independence. Ahmad explains the construction of the top-down and state-centric Republican modernity and the efforts of Mustafa Kemal and his followers to establish a new nation state based on secular reason and legal rational authority. Ahmad provides us with a rich historical and political narrative about the making of a New Turkey in the Early Republican era between 1923 and 1930. Ahmad’s account is also illuminating and illustrative for the making of the New Turkey today, insofar as it helps us see that like the 1920s, the 2000s and 2010s involve a transformation and hegemony leading to a new state, historic bloc, middle classes, and modernity, that is, the New Turkey. Furthermore, the March 30 election, as it has been constructed by the power struggle between the AK Party and the Gülen Hizmet Movement, was played out not as a local election, but as a fight for determining who governs Turkey.

These problems cannot be solved through electoral victories. They require a normative and political commitment to democracy

Of course, the process of making the New Turkey is neither spontaneous, nor linear, nor smooth. On the contrary, it involves a power struggle, or a bitter fight for hegemony, among actors with different visions of Turkey and different programs of modernity, which is carried out by a kind of politics that is shaped by a friend-foe relationship. Similar to Ahmad, Resat Kasaba refers to the ongoing hegemonic fight between the two visions of Turkey.

“Turkey has been pursuing a bifurcated programme of modernisation consisting of an institutional and a popular component which, far from being in agreement, have been conflicting and undermining each other. The bureaucratic and military elite that has controlled Turkey’s institutional modernisation for much of this history insists that Turkey cannot be modern unless Turks uniformly subscribe a same set of rigidly defined ideals that are derived from European history, and they have done their best to create new institutions and fit the people of Turkey into their model of nationhood. In the mean time, Turkey has been subject to world-historical processes of modernisation, characterized by the expansion of capitalist relations, industrialisation, urbanisation and individuation as well as the formation of nation-states and the notions of civil, human and economic rights. These have altered people’s lives and created new and diverse groups and ways of living that are vastly different from the blueprint of modernity that had been held up by the elite. Hence, Turkey’s modernisation in the past century has created a disjuncture where state power and social forces have been pushed apart, and the civilian and military elite that controlled the state has insisted on having the upper hand in shaping the direction and pace of Turkey’s modernization.”7

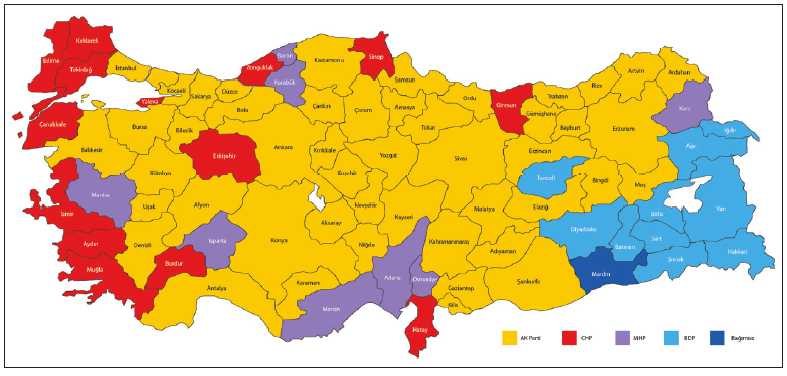

Following Kasaba’s analysis, it is safe to suggest that with the March 30 local elections, the bifurcated program of modernization has almost ended; the society-embedded modernity won over the state-centric top-down modernity; and new political and economic elites have gained the ability to shape the direction of the state and modernity. Rather than a bifurcated modernity, there is a new dominant party with electoral hegemony, able to dictate the state, a new middle classes and a new post-secular or conservative modernity. In this New Turkey, political power is in the hands of the elected government and the military and judiciary are no longer in the position of overseeing politics or possessing tutelary powers; the AK Party is a dominant party with a strong majority government, whose scope of governance covers most parts of Turkey; for the first time since its inception, the CHP is totally excluded from the domain of the stat, has no control or connection with the military and judiciary-based governing elite, and has become a middle class party of New Turkey; the successful peace process and its dominant position in the Kurdish question renders the BDP as a key actor of the New Turkey, capable of initiating an effective opposition to the AK Party; and the MHP is able to maintain its important position among advocates of Turkish nationalism and skeptics of the New Turkey.

Polarization

The New Turkey is not without problems and serious challenges. The most critical and pressing problem is the ongoing and unprecedented level of polarization in the political sociology of the country. Since 2002, every election that the AK Party won resulted in increasing polarization in terms of secularism, ethnicity and religion. The existence of a strong majority government, even of the dominant party, has not strengthened the culture of living together within diversity. On the contrary, as Erdoğan and the AK Party have become stronger, polarization has widened and deepened. The electoral hegemony that has given rise to the dominant party position of the AK party in Turkish politics has also created a polarized Turkey. The New Turkey refers to a dominant party rule or governance within a highly polarized society.

Naturally, polarization has helped Erdoğan to consolidate his constituency and therefore win elections. As an instrumental electoral strategy, he preferred to act in a way that made polarization beneficial to his campaign. However, this strategy comes at a price – strengthening polarization to the point of fragmentation, even division. Turkey has become a highly polarized society with little general trust, creating the risk of becoming a divided society. This is one of the main challenges confronting the New Turkey and its governance by the AK Party and Erdoğan.

Like the March 30 local elections, the 2014 presidential elections and 2015 general elections will increase polarization, as Erdoğan will use polarization to become the first elected President of Turkey. This will be supplemented with the AK Party’s fourth consecutive general election victory. To ensure victory in 2015, Erdoğan has begun to advance a number of legislative reform proposals. One of them is a “single member district” plurality voting, where 550 seats in the legislature are determined by “one candidate for a single seat” or “the winner takes all” approaches. The other is the “narrower and multimember districts” approach, with a 5 percent national threshold. Both systems result in securing electoral hegemony in favor of the AK Party. However, these methods also deepen polarization, as the CHP is squeezed into a small part of the West coast and the BDP into the East and Southeast. As the political map of Turkey below demonstrates, while the AK Party is increasing its seats in the legislature, Turkey’s division into three separate identities is becoming more visible.

Conclusion: Three challenges

However, it should be pointed out that the enduring dominance of the AK Party experience in Turkey has not been without problems or challenges. In addition to polarization, the AK Party rule has not resulted in the consolidation or upgrading of democracy. Instead, it has remained limited and partial, falling short in the areas of rights and freedoms, and the separation of powers, especially between the executive and the judiciary. Freedom House’s most recent Freedom Index reveals that since 2002, Turkey has not graduated from its “partly free” ranking in political rights, civil rights, and press freedoms; on the contrary, numerically its standing has declined. Out of the 7-scale democracy ranking, Turkey’s score has declined from 4/7 to 3/7. Moreover, in the Economist Intelligence Unit’s (EU) Democracy Index, Turkey ranks 88 out of 167 countries as a “hybrid democracy.”

The AK Party’s electoral hegemony and dominant party position has not yielded an effective system of “checks and balances.” Instead, recent debates on presidentialism or semi-presidentialism have indicated that the AK Party and Prime Minister Erdoğan prefer a mode of governance based on the centralized power of the Executive. The problem of normalization, coupled with that of a limited and partial democracy, has increased concern both inside and outside Turkey about the future of Turkish democracy. Whether the AK Party’s rule in Turkey, while carrying out the transformation process, has given rise to the increasing disconnect between the economy and democracy, and produced an “authoritarian Turkey” remains to be seen.

Moreover, recently, especially after the Gezi Protests and the coup in Egypt, a serious problem of trust has emerged between Erdoğan and the West, as well as the international community at large. Although some of the criticisms initiated in the West against Erdoğan seem harsh and unacceptable, it is quite clear that there is a serious problem – a growing disconnect – with the West that confronts not only Erdoğan, but also Turkey’s proactive foreign policy and global image as a model or a source of inspiration for the region. The global turmoil and, in particular, the political crises in Syria, Iraq, Egypt and Ukraine require an active and positive Turkish role for regional and global stability. Turkey, confronted by the problems of polarization, limited democracy and disconnect with the West, is unlikely to play this role.

These problems cannot be solved through electoral victories. They require a normative and political commitment to democracy, the effective system of checks and balances, living together through diversity, and a constructive and soft power based foreign policy. The revitalization of Turkish-EU relations and of the Kurdish peace process are of utmost important in connecting the transformation with democracy, as well as redirecting Turkey’s roadmap towards a culture of living together within diversity rather than polarization and fragmentation, recognizing and implementing pluralism and the entitlement of the other to fundamental rights and freedoms, promoting equal citizenship, and reconnecting with the international community as a constructive soft power. The choice that Erdoğan and the AK Party, as the dominant party in Turkish politics, will make in this respect will determine what kind of “New Turkey” will evolve – hegemonic or democratic.

Endnotes

- Müftüler-Baç, Meltem and E. Fuat Keyman, “The Era of Dominant Party Politics,” Journal of Democracy, 23, (2012).

- Müftüler-Baç, Meltem and E. Fuat Keyman, “The Era of Dominant Party Politics”.

- Gümüşçü, Şebnem, “The Emerging Predominant Party System in Turkey,” Government and Opposition, (2012).

- Müftüler-Baç, Meltem and E. Fuat Keyman, “The Era of Dominant Party Politics”.

- Keyman, E. Fuat and Şebnem Gümüşçü, Democracy, Identity, and Foreign Policy in Turkey, (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2014).

- Feroz Ahmad, The Making of Modern Turkey, (London: Routledge, 1982).

- R. Kasaba, “Introduction”, in R. Kasaba (ed) The Cambridge History of Turkey: Volume (4), (Cambridge: Cambridge University Pres, 2008), p.1.