Introduction

One of the most vital factors for the EU to achieve its desire to expand the integration process from its original field of economics to other areas, and ultimately to reach its ideal of a fully-fledged union, is sufficient support and loyalty from the populace of member and potential member states. Consequently, what people in member and candidate states think about EU-related issues, and how they position the EU in the context of their own world –that is to say their orientation toward the EU– is a critical matter. In the case of a country such as Turkey, which has been waiting at the EU’s door for quite some time, and has been the subject of perhaps the most discussions on whether or not it should be a member, the matter of the Kurds becomes one that specifically needs to be addressed.

One of the most important priorities concerning EU membership at the national level in Turkey is the rights and freedoms of the Kurds living in Turkey. Since the Kurdish people are critically positioned both in terms of Turkey’s internal dynamics and its relationship with the EU, the Kurds own orientation toward the EU is a matter that needs to be assessed specifically and separately from that of the overall general public.

Based on a comprehensive study carried out in Turkey’s southeast cities where the Kurdish populace mainly resides, this paper seeks to analyze the type and extent of Kurdish orientation toward the EU in that part of the country.1 It consists of three sections; the first section conveys how people’s orientation toward the EU, emerged as a necessity and how this was addressed theoretically. The second section offers information on Turkey’s EU accession process and the place of the Kurdish question within it, and describes both the relevant literature in Turkey and parameters of the present study. Finally, a detailed analysis of the Kurdish orientation toward the EU, based on the findings from our study, is presented in the final section.

Orientation toward the EU: Historical Background and Content

The European cooperation movement that embarked in the 1950s was elite-driven and based on an understanding of gradual progress; by the late 1960s, it had achieved significant economic gains in terms of establishing a customs union and providing prosperity to member state populations. Due in part to this success –and in accordance with its initial understanding– the political elite, academics, and other relevant circles became increasingly more vocal in the early 1970s to both deepen the cooperation movement in the financial domain, and expand it to non-financial areas. While matters related to deepening and expanding this integration process were being discussed during this period, another related issue that inevitably came to the fore was the public opinion about the process itself; what member state populations thought about the EU project, and how their support could be increased. This was because more advanced integration would be possible only if member state populations cared about and backed the EU, and ultimately converged at a common understanding of being European.

In the case of a country such as Turkey, which has been waiting at the EU’s door for quite some time, the matter of the Kurds becomes one that specifically needs to be addressed

At the Paris Summit2 held in October 1972, which was the first summit held by the nine-member EU, a resolution was made to further boost political cooperation, while the need to ensure that citizens were more actively included in the process and held a positive orientation toward the EU was also emphasized.3 From then on, discussions concerning public opinion and people’s orientation toward the EU continued hand in hand with efforts to create a broader common identity and sense of belonging on the one hand, and increase the EU’s democratic outlook on the other. These matters gained momentum specifically after the 1990s, and the issue of how people justified being for or against the EU –not only in member states but candidate states as well– was often on the public agenda. The fact that Eurobarometer surveys were administered to gauge people’s views on matters related to the EU in member states from 1973 onwards, in central and eastern European countries from 1990 onwards, and in all candidate nations from 2001 onwards can be considered a clear reflection of the EU’s objective to take public opinion into consideration. Other examples include the fact that members of the European Parliament have been elected by the public since 1979, and that referendums are the preferred choice when it comes to any critical steps the EU plans to take. In addition, knowing people’s orientation toward the EU is especially important in candidate nations so as to ensure that the accession process runs smoothly.

The issues described above in terms of the EU praxis have been extensively addressed in academic circles. The focal point of all the discussions and studies concerning the peoples’ orientation toward the EU basically comes down to one single question:4 What are the expectations underlying people’s support for the EU? In general, two main groups of expectations have emerged from these discussions. The first is that people’s orientation toward the EU –for or against– is shaped on the basis of economic-utilitarian expectations. The second group extends beyond personal utilitarian expectations, and concerns being for or against the EU on the basis of mostly abstract-idealist gains or losses. Let us now take a more in-depth look at these two groups of expectations.

Kurds desire to get to know the EU and learn about relevant developments, yet are aware that they are unable to meet this desire due to various reasons, and thus believe their level of knowledge is low

Due to human nature, it makes sense that people think about personal and familial prosperity first and foremost, and act according to various financial expectations. Consequently, it is understandable that people hold and even prioritize certain utilitarian-economic expectations that shape their orientation toward the EU. The utilitarian-economic expectations that Ronald Inglehart –a leading name often referred to in issues concerning orientation toward the EU– calls “materialist values,” which are exemplified in efforts to seek financial prosperity and physical safety,5 can be found in Niedermayer and Westle’s6 frequently cited orientation typology, and many other studies as well.7 As we noted earlier, the first objective of the European integration movement was to offer citizens of member states certain gains in the economic domain so that they felt closer to the movement,8 and ultimately arrived at common identity characteristics resulting from the cooperation based on these gains.9 In fact, some have even examined orientation toward the EU directly in terms of economic expectations, based on the idea that European integration focuses on economics first and foremost, and unlike nation states, lacks a strong foundation in terms of an abstract-idealist orientation.10

Although a utilitarian-economic orientation may be what is rational, expected, and even necessary to a certain extent in terms of ensuring public support for European integration, there is also a need for a type of orientation that is not based on loss-profit calculations and perhaps offers a stronger bond than a reversible utilitarian-economic orientation. At this point, abstract-idealist support emerges not simply on the basis of certain financial expectations, but by including evaluations of emotional-spiritual gains and values.11 Determining the drivers of an abstract-idealist orientation is not as easy as determining the drivers of a utilitarian-economic one, because detecting and measuring these drivers is rather difficult. Instances where people develop expectations on the basis of national sovereignty or culture, or on the basis of values such as peace and democracy instead of economic gains, could be considered examples of being for or against an idealist stance.12 The approach that Inglehart13 conceptualizes as “post-materialist values,” which include such concerns as caring for human rights, the freedom of expression, political participation, etc., can be considered another way to explain the idealist orientation.

Undoubtedly, the level and context of people’s support or opposition toward European integration can be shaped not only by economic or value-based expectations, but also by many other parameters, as argued in the literature: class partisanship and support for national government,14 national identity,15 the role of national elites,16 perceived cultural threat,17 media coverage about the EU,18 and so on. However, the predominance and robustness, foremost of utilitarian and then of idealist expectations, is notable across the relevant literature.19 Moreover, the idealist orientation covers some of the aforementioned parameters, such as national identity, cultural threat, etc.

Representatives of Turkey and the European Union held a High-Level Political Dialogue meeting in Brussels, on July 25, 2017. AHMET GÜMÜŞ / AA

The concept of orientation toward the EU is actually more comprehensive than attitudes of simply being for or against the EU. We believe that Niedermayer and Westle’s20 typology of orientations best illustrates just how broad this issue is. According to these authors, people first have to be interested in and know about a political object (in this case, the EU) in order to be able to assess that object on the basis of certain economic or non-economic expectations and arrive at a certain attitude. This neutral orientation or initial psychological involvement as termed by the authors is the first level where interest in (awareness of) and knowledge about the EU begins to form. Inglehart also emphasizes the same thing when he notes that high political awareness and political communication –which also includes knowing about EU related issues– were skills that were a prerequisite to supporting the EU. He argued that people who were highly aware of and more knowledgeable not only discussed EU-related matters more, they even gradually began to assess these matters from a European perspective.21

Parenthetically it can be added that apart from neutral and evaluative orientations, there is a further mode of orientation in Niedermayer and Westle’s22 typology, namely that of “behavioral intentions,” which refers to “all actions which might be taken with different degrees of subjective probability” regarding the EU. However, most of the usual activity types in this circumstance, for example voting in the European Parliament elections, signing a petition to the EU institutes, applying to the Court of the EU, joining an EU-related demonstration, are not practicable for people in Turkey and, thus, there is no need to take this mode into account.

Kurds residing in eastern and southeastern Anatolia are highly or at least partially interested in the EU, but lack life experience in staying in an EU country and are insufficiently informed about the EU

To summarize, orientation toward the EU is first and foremost a concept that describes people’s levels of awareness and knowledge about the EU. In addition, it emphasizes the state of being for or against the integration process and the EU, on the basis of various utilitarian-economic or idealist expectations. One of the necessary factors to further the European integration process is for citizens of member or candidate states to be favorable in their orientation toward the EU. Although it is normal for favorable orientations to be shaped primarily by utilitarian-economic expectations, an orientation based on stronger and more permanent idealist expectations needs to gain hold among the citizens of member and candidate states if the EU project is to expand and be sustained.

The EU Membership Process, the Kurdish Question, and Public Opinion

Turkey’s EU accession process began in July 1959, when Turkey applied for associate membership, and it has continued to the present day at fluctuating speeds, while always ranking high among items on the nation’s agenda. Ever since 1999, when Turkey became a candidate and was observed more closely in terms of EU harmonization on the basis of the acquis communautaire, (the accumulated body of European Union law and obligations) resolving problems related to the rights and freedoms of the Kurds in Turkey has been one of the main headings in this process. The beginning of the problems related to Kurds is based on the understanding of Turkey as an ‘ethnically homogeneous nation’ –one of the founding principles of the Republic established in 1923– as a result of which even the fact that Kurds have separate ethnic identities was ignored for a long time. The Kurds have revolted against such politics of denial and suppression or tried to resist them in other ways, over the years, causing ethnic tensions to rise and fall since the birth of the Republic. From the mid-1980s through much of the 1990s, the dominant picture in terms of the Kurdish question was that of continued armed conflict, especially in Turkey’s eastern and southeastern Anatolian regions where the Kurds primarily reside; this conflict was accompanied by severe loss of life and property.

This bleak picture became relatively less dominant, and significant steps were taken toward resolving the problems related to the Kurds, during the few years between December 1999, when Turkey was awarded EU candidate status, and October 2005, when the negotiation process began. With the harmonization reforms undertaken during this period, advances incomparable to past efforts were realized in the granting of a number of political and cultural rights and freedoms to the Kurds. Meanwhile, the EU kept the issue always on the agenda, thanks primarily to annual reports. After 2005, the reform process in Turkey began to slow down and the process of negotiations almost came to a full stop due to various reasons. In terms of the Kurdish question, a new era of conflict has recently arisen –perhaps even more severely than before. However, although Turkey’s relationship with the EU is currently not very hopeful, EU membership –of critical importance in Turkey’s longstanding overall paradigm that concerns its standing among modern Western nations– is still a valid objective. This is why it is still crucial to know people’s orientation toward the EU in Turkey and develop policies accordingly, given that Turkey is a nation at the negotiations level, which could be likened to a final bend in the road to membership. Moreover, what Kurds think about the EU and the point Turkey has reached in its membership process are also vital, due to their key function in terms of both Turkey’s internal dynamics and its relationship with the EU, as was briefly summarized above. Accordingly, we will attempt to analyze the Kurdish orientation toward the EU in this paper, on the basis of a comprehensive research study carried out in nine provinces in Turkey’s southeast region. Before moving on, however, it will be useful to briefly touch on the current state of the relevant literature on this issue in Turkey, and on the parameters of the present study.

The first studies that addressed what people in Turkey thought about the EU began to emerge in the 1990s, but were very limited in terms of both scope and number.23 Due to the political circumstances of the time, it was not really possible to address Kurds as a separate subgroup in these early studies. From the 2000s onwards, publications that took the public opinion about the EU or EU-Turkey relations into account gained noticeable momentum. It must be said that in the majority of these studies, analyses were carried out on the basis of Eurobarometer data;24publications based on independent field studies remained relatively limited in number. The field studies that did emerge overcame the problem of addressing the Kurds as a separate subgroup, distinguishing them on the basis at least of certain indirect questions, such as political party membership or language spoken.25

While over 60 percent of the Kurds supported EU membership, only 25.8 percent found the EU trustworthy, and only 17.4 percent thought the EU was fair and sincere in its treatment of Turkey

In recent years, a few studies have emerged on the Kurdish orientation toward the EU, where Kurds were directly the subject matter. All of these studies, however, addressed a specific group of Kurds and examined, for instance, the EU orientation of university seniors26 or those with at least a university degree.27 It should also be noted that all these studies were carried out only in one or few cities. In contrast, all Kurds over the age of 18 constitute the subject matter of the field study that informs this paper. A comprehensive 25-question survey was administered to 650 randomly selected Kurdish individuals in nine provinces through face-to-face interviews. 650 samples were distributed to these nine provinces taking their population into account: Şanlıurfa (145), Diyarbakır (112), Van (91), Mardin (80), Batman (59), Ağrı (54), Bitlis (31), Siirt (29), and Şırnak (49). We selected these provinces because these are the ones where Kurds mainly reside, and where the political and social presence of the Kurdish issue shows itself more. For example, with the exception of Şanlıurfa, all the selected provinces were the places where the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (Halkların Demokratik Partisi, HDP) came first in the November 2015 parliamentary elections (the party also gained almost one-third of the votes in Şanlıurfa). Although there were four other provinces in the same context, due to some hindrances, i.e. budget constraints and safety risks, we were unable to survey Muş, Iğdır, Tunceli and Hakkari, and we determined that the selected nine provinces were representative enough geographically. Considering all these factors, it could be said that our study is the first of its kind and that consequently, our paper will make significant contributions to the literature.

Our fieldwork was conducted in August and September of 2016 by a five-person research team. In some local areas, we collaborated with academic colleagues to reach respondents. The fieldwork had been planned to start in mid-July. However, Turkey was exposed to a serious military coup attempt on July 15, 2016. Thus, we had to postpone some of our trips for a few weeks. Apart from this postponement, the survey was pursued as planned.

The Turkish language is widely known and used among the Kurds. Therefore, the survey was prepared and conducted in Turkish. However, in case of needing translation into Kurdish on some rare occasions, the language was not an obstacle to carry on interviews because four of five researchers, as well as the local colleagues, were ethnically Kurdish and had dual native languages, Turkish and Kurdish. The other researcher was ethnically Turkish. Although we found our respondents mostly in city centers, sometimes we also visited some rural areas and small towns on our route.

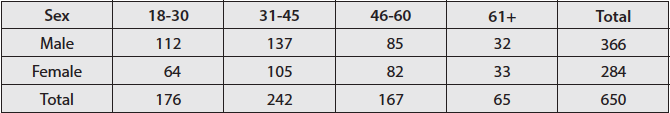

Table 1 shows the age and sex distribution of the respondents. Educational level was another parameter used to establish the respondents’ profiles. While over 12 percent of the participants had no graduation from any school, which confirms the high illiteracy rate of the region,28 almost 27.5 percent of those surveyed had graduated from primary school, and 40 percent from secondary school. A little over one-fifth of participants had at least a university degree.

Table 1: Distribution of the Respondents by Age and Sex

Kurdish Orientation toward the EU

Interest in and Knowledge about the EU

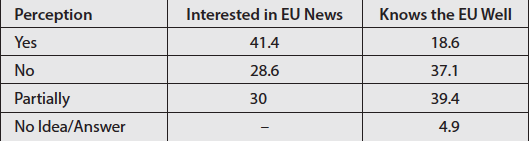

The first phase in analyzing Kurdish orientation toward the EU involved addressing the Kurds’ interest in and knowledge about the EU, i.e. their level of awareness. We believe that the point at which to initiate this awareness analysis is the point people situate their interest in and knowledge about the EU in the context of their own perceptions (Table 2). In other words, are people interested in the EU, do they think they know the EU well enough? When survey respondents were asked whether they were sufficiently informed about the EU, less than one-fifth (18.6 percent) said ‘yes,’ 37.1 percent said ‘no,’ and 39.4 percent said they were somewhat informed about it (the remaining 5 percent said ‘no response’). Meanwhile, when asked whether they were interested in news about the EU, a significant number of the participants (41.1 percent) said ‘yes’ and 30 percent said ‘somewhat.’ The remaining 28.6 percent stated they were not interested in news about the EU.

Table 2: Self-Perception of EU Awareness (%)

As these figures show, most of the respondents thought they were insufficiently informed or only partially informed about the EU. Nonetheless, over 70 percent were either partially or very interested in news about the EU. What can be deduced from these findings is that Kurds desire to get to know the EU and learn about relevant developments, yet are aware that they are unable to meet this desire due to various reasons, and thus believe their level of knowledge is low. For even among those who stated an interest in EU-related news, only 32.3 percent of the respondents considered themselves as being sufficiently informed.

Respondents were asked to rate their self-perceptions on EU awareness, i.e. how well do they actually know the EU, how informed are they about it? To provide some background, from the start, the EU has aimed to help citizens of member and candidate states get closer and get to know one another, and to this end, put into effect many tools geared to encouraging travel to EU states and enhance orientation toward the EU. Meanwhile, means of transportation have recently significantly increased, and cities in eastern and southeastern Anatolia have witnessed important infrastructural gains in terms of both overland and air travel. Finally, according to estimates, there are over one million diaspora Kurds in Europe, most having migrated from Turkey.29 Given that the Kurds are a people with strong family bonds, it is likely that respondents know people who could offer them assistance, if not accommodation, in EU countries. Yet a great majority of Kurds (almost 92 percent) had never been to an EU country, not even for a short stay. Of those remaining, 3.8 percent had visited one country, 1.4 had visited two countries, and only 3.1 percent had visited more than two countries. In other words, their relationship with the EU landscape has remained extremely limited in physical terms. Women’s mobility was especially low (2.6 percent). The fact that only a very few among the young population had visited EU countries (1.8 percent) despite having the option to benefit from educational and youth programs, indicates that these programs have yet to become fully accessible in Kurdish cities. Although it might seem the most likely option to associate the low rates of EU country stays mainly with financial difficulty, the fact that this rate continues to remain low among those who are financially well-to-do shows that the community still maintains its traditional, closed structure; even among respondents who earned over 5,000 TL a month, 91 percent had not stayed in an EU country.

Given that the membership and reform processes have lost their past momentum and no serious change seems forthcoming in the near future, Kurds presently feel somewhat disappointed in the EU

To assess their level of knowledge about the EU, respondents were asked two questions that are often cited in the relevant literature. The majority of the respondents answered the visual question on recognizing the EU flag correctly (about 88 percent). Yet this rate is low compared to the rate of correct answers currently given in EU countries (98 percent).30 When asked how many members the EU presently had, close to 93 percent of the respondents gave the wrong answer, despite the fact that for years, membership to the EU has been Turkey’s most important foreign policy route.31 Compared to the rates of correct responses given in EU member states and in Turkey overall (68 percent and 45 percent, respectively) in the Eurobarometer study32 conducted around the time of our field study, a correct response rate of 7 percent among the Kurds is clearly very low.

To summarize, Kurds residing in eastern and southeastern Anatolia are highly or at least partially interested in the EU, but lack life experience in staying in an EU country and are insufficiently informed about the EU. Consequently, we should note right at the start that their subjective evaluations of the EU and their views on being for or against it were decided on the basis of a limited awareness of the union.

Subjective Orientation toward the EU

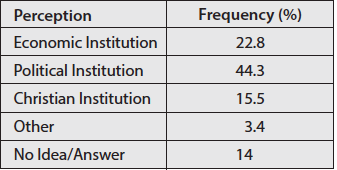

To uncover how Kurds evaluate the EU, and which of their expectations play a role in shaping their subjective orientation to it, we tried to shed light on the issue by asking more and more varied questions. First, we made an effort to determine what type of institution the EU was in the eye of the respondents (Table 3). Many viewed the EU primarily as a political institution (44.3 percent). The rate of respondents who saw the EU mainly as an institution with economic objectives trailed very far behind, at 22.8 percent. The fact that only 15.5 percent of the respondents said the EU was a Christian institution first and foremost indicates that Kurds did not corroborate the oft-discussed argument that the EU is a Christian club and that this is the true obstacle to Turkey’s full membership. While some 3.4 percent offered different answers on the primary feature of the EU, 14 percent said they had no idea on the matter.

Table 3: The Primary Perception of the EU by the Kurds

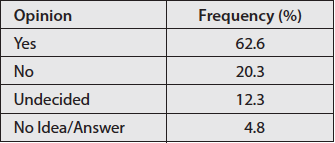

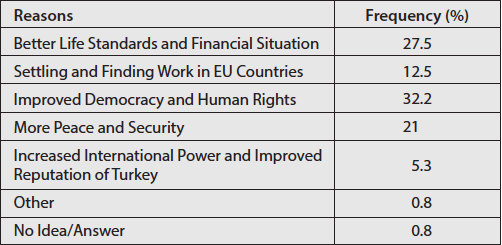

The fact that the EU was viewed as a structure that comes to the fore primarily with its political and economic objectives could perhaps offer some ideas about the underlying justifications concerning their orientation to the EU. In fact, the results that emerged when asked about the two most important reasons they would say either ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to membership in a hypothetical EU referendum overlap to some extent with views on the type of institution the EU is. Before moving on to the reasons provided by the respondents, let us look at their views on the referendum (Table 4). While the majority (62.6 percent) said they would vote to join the EU if a referendum was held tomorrow, 20.3 percent were against it, and 12.3 were undecided (the remaining 4.8 said they had no idea). When national averages are taken into account, where support for joining the EU is very low (39 percent), and some 26 percent is against it,33 it becomes clear just how high the rate of support is among the Kurds.

Table 4: Kurdish Support for a Hypothetical EU Referendum

Respondents who would vote ‘yes’ in the referendum were asked to provide the two most important reasons that formed the basis of their decision;34 of them, 27.5 percent said their life standards and financial situation would improve, and 12.5 percent said opportunities to settle and find work in EU countries would increase. In other words, utilitarian-economic expectations were found to influence decisions to support EU membership by 40 percent. However, 32.2 percent said democracy and human rights would improve, 21 percent said peace and security would increase, and 5.3 percent said Turkey’s international power and reputation would improve. Accordingly, idealist expectations comprised some 58.5 percent of the total. Those who offered no reasons for their choice or gave no answer were less than 2 percent.35

Table 5: Most Important Reasons of ‘Yes’ Voters

It is usually quite normal for people –especially those from a low socio-economic background– to prioritize economic expectations in their desire to join the EU. This kind of utilitarian orientation is easily observable in many different countries.36 However, the fact that idealist expectations are this high, in the foreground even, for Kurds, is linked entirely to the special conditions under which they live. Yearning for democracy and human rights on the one hand, and peace and security on the other, it is a direct reflection of the conditions Kurds find themselves in. As is the case with many different ethnic minorities that wait in vain for their state to take constructive steps in terms of democratic and cultural rights and freedoms,37 the Kurds also clearly support EU membership with hopes of embracing various rights and freedoms that they have long been demanding and fighting for. When the pursuit of peace and security, brought on by the recently renewed conflicts, is added to the picture, it becomes apparent why even Kurds with the lowest of incomes prioritize idealist expectations; in households with monthly incomes less than 1,000 TL, 29.4 percent of the respondents cited expectations related to democracy and human rights, and 20.6 percent hoped for more peace and security, while 31 percent cited improved life standards, and 8.6 percent noted the possibility of settling and job opportunities in EU countries. Apparently, observations that the EU is primarily a political institution, and citing politics-laden idealist expectations more than average in support of membership, complement one another.

Meanwhile, the narrow 20 percent who said they would vote ‘no’ in the referendum justified their choice mostly on the basis of utilitarian-economic reasons: Some 27 percent said economic resources would be handed over to foreigners, 17 percent said agriculture and small industry would suffer harm, and 11 percent said unemployment would rise. However, through idealist reasons, still 27 percent said national identity and culture would weaken and 13 percent said national sovereignty would weaken. Other responses and those who did not answer constitute 4 percent of the sample.

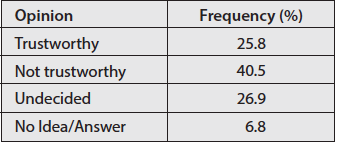

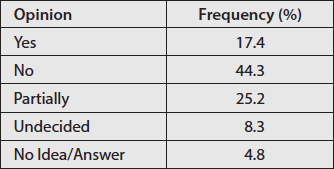

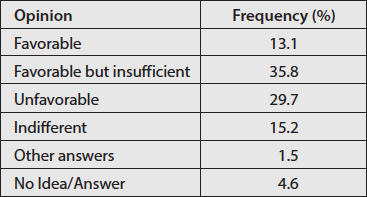

The Kurds’ responses to three questions that were asked one after the other –‘Is the EU a trustworthy institution?’ (Table 6), ‘Is the EU fair and sincere toward Turkey?’ (Table 7) and ‘What is your view of the EU’s approach to the Kurds in Turkey and their probable problems?’ (Table 8)– paint quite an interesting picture: While over 60 percent of the Kurds supported EU membership, only 25.8 percent found the EU trustworthy, and only 17.4 percent thought the EU was fair and sincere in its treatment of Turkey. The fact that 40.5 percent did not see the EU as a trustworthy institution, close to 27 percent were ‘undecided’ and nearly 7 percent said they had ‘no idea,’ shows that there is a serious problem related to trusting the EU. Similarly, the fact that 44.3 percent thought the EU was unfair and insincere in its treatment of Turkey, 25.2 percent said ‘partially,’ 8.3 percent were ‘undecided’ and 4.8 percent had ‘no idea,’ confirm this problem. Moreover, nearly one-third of the respondents (29.7 percent) found the EU’s approach to Kurds and their probable problems unfavorable, and 15.2 percent said the EU was ‘indifferent.’ Of the respondents, 35.8 percent found the EU’s approach favorable but insufficient. Only 13 percent said the EU was favorable in its approach to Kurds and their problems.

Table 6: The Trustworthiness of the EU

Table 7: Fairness and Sincerity of the EU toward Turkey

Table 8: Approach of the EU to the Kurds

These results shed light on the Kurdish people, who have serious trust concerns when it comes to the EU and who are not really all that satisfied with how the EU specifically approaches their situation, but who still support EU membership. This paradoxical outcome can be interpreted in a number of different ways: First, the Kurds are aware that the largest reforms ever to occur in the history of the Republic –in terms of the national population in general and their own rights and freedoms in particular– took place during the first half of the 2000s, within the framework of the EU membership process; so under the influence of that era, they still support joining the EU. During that time, it can be said that Kurds were more interested in and supported the EU much more than today.38 This interest and support was so clear that in the words of an expert who monitored performance related to contacting EU institutions and advocating for their rights, many Kurds were acting as though they were EU citizens.39 However, given that the membership and reform processes have lost their past momentum and no serious change seems forthcoming in the near future, Kurds presently feel somewhat disappointed in the EU. This change of attitude from a pro-EU position to an in-between one among the Kurds began after 2005, and may be attributed to certain reasons, i.e. the designation of the PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) as a terrorist organization by the EU institutes and the Kurds’ skepticism about the effectiveness of the EU’s influence on Turkey to continue EU reforms.40

While the Kurds are somewhat distrustful and skeptical toward the EU, they continue to support EU membership or remain undecided about it due to past gains

When respondents were asked when Turkey might become an EU member, almost two-thirds (65.1 percent) said ‘never’ while 19.2 percent noted that this would not happen for at least ten years. Those who said between five and ten years were at 6.3 percent, while only 2.2 percent thought EU membership could be achieved in less than five years. These percentages indicate just how hopeless Kurds feel concerning the EU membership process, while their responses to whether the EU was fair and sincere in its treatment of Turkey –discussed above– illustrates that they hold the EU at least partly responsible for this. As it is, after observing a series of developments ranging from the conditions demanded of no other country up to that point in the Negotiation Framework, to some member states making Turkey’s membership conditional on holding a referendum, there are some in Turkey, both Turks and Kurds alike, who hold a perception that from 2005 onwards, the EU has been applying double standards to Turkey and has intentionally slowed down the process.41

Consequently, while the Kurds are somewhat distrustful and skeptical toward the EU, they continue to support EU membership or remain undecided about it due to past gains. However, it must be said that it is not only the EU they hold responsible for no longer having faith in the membership process. When asked how they evaluated the Justice and Development Party’s (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AK Party) EU policies (the party has been in power since November 2002) 37.5 percent said ‘inadequate,’ while 30 percent found it somewhat adequate. One-fifth of the respondents (21.4 percent) found the policies adequate, and respondents who were undecided or had no idea made up 11 percent of the sample.

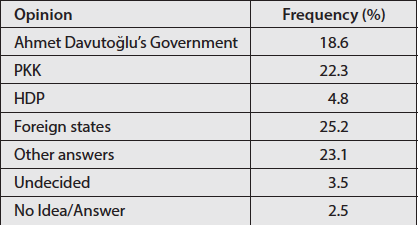

The fact that the Kurds continue to strongly support EU membership despite their lack of trust in the EU and their unfavorable views concerning the EU’s attitudes toward them, may have another explanation: the great hopelessness felt toward the state and their own representatives due to the armed conflict that has recently intensified once again, and the fact that the resumption of the conflict resolution process remains ever elusive. These factors propel the EU to the forefront despite all else. In fact, when respondents were asked who was primarily responsible for the conflicts that started off once again in June 2015, Kurds were observed to feel confused and disorganized, which is a reflection of the distrust and despair they feel toward all the parties of the conflict (Table 9). While 18.6 percent of the respondents primarily held the Justice and Development Party government responsible, 22.3 percent said the PKK, and 4.8 percent said the HDP which follows the PKK, was responsible. A quarter of the respondents (25.2 percent) held foreign states responsible, while another quarter (23.1 percent) gave open-ended answers to this question. Most of the open-ended answers accused both the government, and the PKK and the HDP. Some 6 percent were undecided or gave no response.

Table 9: Who is Responsible for the Conflicts of Recent Date?

Another piece of data that can be considered evidence of why Kurds have no hope in domestic politics and still see the EU as a source of hope despite having trust concerns is this: While 26.5 percent of the Kurds think the possibility of a new peace process is impossible, 44.2 percent think this is a low possibility, and less than one-fourth (23.1 percent) feel hopeful that a new process will begin. The remaining 5 percent consists of respondents who are undecided or have no idea about the issue. Taking all this data into consideration, it could be said in summary that for the Kurds, who have no trust in domestic actors either, the EU seems to be playing the role of a lesser evil.

The perception that it is impossible, or at least very difficult, for a country situated in the Islamist-Eastern basin to adapt to the democratic and liberal values of Europe, is still prevalent in the minds of many EU citizens, as a result of which they oppose Turkey’s membership

Another explanation for the paradoxical attitude in the Kurds’ orientation toward the EU could be this: Although the expectations of the Kurds can be found in an idealist framework on an axis of rights, freedoms, and peace, in this context, the EU plays a more instrumental role. In other words, the pursuit of rights and security is the real deal, and EU membership is a means to this end. Yet EU membership can also become less important for the Kurds, if they think they can meet their expectations through other means. In fact, when Turkey’s foreign policy alternatives were listed in our survey and respondents were asked which option was the most profitable, EU membership was still the most frequently repeated answer –but at a reduced rate of 47.5 percent compared to ‘yes’ answers of the referendum question. 21 percent of the respondents thought the most profitable way would be to unite with Islamist countries, 10.3 percent thought to unite with Mesopotamian countries, and 12.9 percent wanted Turkey to remain a neutral country. So while Kurds might be suspicious of the EU’s trustworthiness, and perhaps even think that the EU fails to specifically focus on their problems, they still see the EU as a valid gateway that leads to the freedoms and peace they long for.

Among other buildings, the PKK militants destroyed the historical Kurşunlu Mosque in Diyarbakır, southeast of Turkey, in 2015. It was subsequently restored by the Turkish government. DURSUN AYDEMİR / AA

In addition to all these explanations about subjective orientation, examining the referendum question in terms of age, gender, and educational criteria, certain points come to the fore: Noticeable differences did not arise in the age groups from 18 to 60; support for membership was in the range of 60-66 percent in all groups. Among those above 60 years of age, however, support for EU membership dropped to below 50 percent (49.2 percent). In addition to the fact that the elderly tend to be more resistant to change, this can also be explained by the fact that they have observed the unending story of the EU membership process for a longer time. While about 65 percent of all participants said ‘never’ in response to the question of when Turkey might become an EU member, this rate climbed to 84 percent in the age group above 61.

Among Kurdish women, support for EU membership is around 55 percent. Although this percentage is much higher than the overall national average, it still falls behind that of Kurdish men (68 percent). Compared to men, women are much more undecided (8 percent and 17 percent, respectively). Education might be a parameter that can help explain why women support the EU less. The validity of the positive correlation between education level and support for the EU is accepted in the literature.42 Results from our study also confirm this correlation. While support for the EU from respondents with little to no schooling was at 41.2 percent, it was 59.2 percent among primary school graduates, and 65.3 percent among high school graduates. Among Kurds who hold a university degree, 74.8 percent said they would vote ‘yes’ in a referendum on EU membership. Women’s education level in predominately Kurdish cities is much below national averages, as clearly evinced by the official statistics of the state.43 From this point of view, it seems reasonable to deduce that women support the EU relatively less than men on the basis of differences in education.

Conclusion

Turkey traditionally ranks above all others in terms of countries whose membership is not at all desired by EU citizens. Opposition to Turkey’s membership is largely influenced by a perception of differences based on values, i.e. idealist reasons.44 In other words, the perception that it is impossible, or at least very difficult, for a country situated in the Islamist-eastern basin to adapt to the democratic and liberal values of Europe, is still prevalent in the minds of many EU citizens, as a result of which they oppose Turkey’s membership. Meanwhile, our study shows that the group of people within Turkey that wishes to join the EU the most, and who base that wish on idealist expectations, is the Kurds (at least those Kurds who live in the southeast part of the country). Taking note of and monitoring any changes in the orientation analyses of a group of people who are from a country least desired to become a member on idealist grounds, yet who desire EU membership the most, again on the basis of idealist reasons, could be important in terms of both the EU and Turkey, as is explained below.

While Kurds might not evaluate the EU, and ultimately, their orientation toward it, on the basis of having sufficient knowledge, they do so, on the basis of their own needs and expectations

Regardless of whether the subjective orientation of the Kurds toward the EU was for or against, one important and concrete finding we can note right at the start is that this orientation is based on low education levels, and consequently, that it did not emerge through a healthy process of knowledge, definition, and evaluation. Even so, this does not mean that the Kurdish orientation toward the EU has no meaning. While Kurds might not evaluate the EU, and ultimately, their orientation toward it, on the basis of having sufficient knowledge, they do so, on the basis of their own needs and expectations. Taking into account how much space their peace- and rights-based needs and expectations occupy within the whole, it is important to know where they situate the EU in meeting these needs and expectations. In a candidate country currently in the middle of the negotiations process, the fact that a group of people who support the EU on an idealist basis have recently become less enthusiastic about the EU, and even assumed a more suspicious stance, could be considered a serious warning to the EU about reviewing its own policies.

The fact that the orientation outcomes put forth in this paper constitute a warning for Turkey as well may be explained as follows: While the EU reform process came to a halt after 2005, no progress has been made in the peace process at the national level despite numerous attempts since 2009 either, leaving the Kurds dissatisfied and disillusioned concerning their longstanding quest for rights and freedoms. To prevent even more destructive social disintegration, demands for peace and democracy must be met either through internal dynamics, or by accelerating the EU harmonization process once again.

An additional recommendation that might be gleaned from our study is to create channels that impart correct information concerning public interest and reduce lack of knowledge. Lack of knowledge not only creates a serious gap between the political elite that shapes the EU’s membership strategy and the public, but also prevents the public from engaging in the process more constructively. In the likelihood that Turkey becomes an EU member, Kurds will become the residents of the most eastern edge of an expanded EU; thus we believe that keeping track of their thoughts and ideas about the EU regularly and in detail will become a necessary academic undertaking.

Endnotes

1. The research was supported by the Mardin Artuklu University Scientific Research Projects Unit with the Project number MAÜ-BAP-16-İİBF-04.

2. Although the EU’s first expansion, which involved Britain, Denmark, and Ireland, officially began on January 1, 1973, these countries attended the Paris summit as though they were EU member states.

3. Commission of the European Communities, “The First Summit Conference of the Enlarged Community,” Bulletin of the European Communities, Vol. 5, No. 10 (1973), pp. 9-27.

4. Liesbet Hooghe and Gary Marks, “Calculation, Community and Cues: Public Opinion on European Integration,” European Union Politics, Vol. 6, No. 4 (2006), pp. 419-443.

5. Ronald Inglehart, The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles Among Western Publics, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977).

6. Oscar Niedermayer and Bettina Westle, “A Typology of Orientations,” in Oscar Niedermayer and Richard Sinnot (eds.), Public Opinion and Internationalized Governance, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), pp. 33-50.

7. Alasdair Smith and Hellen Wallace, “The European Union: Toward a Policy for Europe,” International Affairs, Vol. 70, (1994), pp. 429-444; Matthew J. Gabel, “Public Support for European Integration: An Empirical Test of Five Theories,” The Journal of Politics, Vol. 60, No. 2 (1998), pp. 333-354; Gary Marks, “Territorial Identities in the European Union,” in Jeffrey Anderson (ed.), Regional Integration and Democracy, (Boulder: Rowman and Littlefield, 1999); Lauren McLaren, Identity, Interest and Attitudes to European Integration, (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006).

8. Rainer M. Lepsius, “The Ability of A European Constitution to Forge A European Identity,” in Stelio Mangiameli and Hermann-Josef Blanke (eds.), Governing Europe under a Constitution, (Berlin: Springer, 2006), pp. 23-37.

9. Richard K. Herrmann and Marilynn B. Brewer, “Identities and Institutions: Becoming European in the EU,” in Richard K. Herrmann, Thomas Risse and Marilynn B. Brewer (eds.), Transnational Identities: Becoming European in the EU, (Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 2004), pp. 1-22.

10. Matthew J. Gable, Interests and Integration: Market Liberalization, Public Opinion, and European Union, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1998).

11. Niedermayer and Westle, “A Typology of Orientations,” p. 49.

12. Lauren Mclaren, “Explaining Opposition to Turkish Membership of the EU,” European Union Politics, Vol. 8, No. 2 (2007), pp. 251-278.

13. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution.

14. For explanation and testing of these parameters, see, Gabel, “Public Support for European Integration: An Empirical Test of Five Theories.”

15. Sean Carey, “Undivided Loyalties: Is National Identity an Obstacle to European Integration?,” European Union Politics, Vol. 3, No. 4 (2002), pp. 387-413.

16. Hooghe and Marks, “Calculation, Community and Cues.”

17. Lauren McLaren, “Public Support for the European Union: Cost/Benefit Analysis or Perceived Cultural Threat?” The Journal of Politics, Vol. 64, No. 2 (2002), pp. 551-566.

18. Rens Vliegenthart, Andreas Schuck, Hajo G. Boomgaarden and Claes H. De Vreese, “News Coverage and Support for European Integration, 1990-2006,” International Journal of Public Opinion Research, Vol. 20, No. 4 (2008), pp. 415-439.

19. Gabel, “Public Support for European Integration: An Empirical Test of Five Theories”; McLaren, “Identity, Interest and Attitudes to European Integration; Hajo G. Boomgarden, et al., “Mapping EU Attitudes: Conceptual and Empirical Dimensions of Euroscepticism and EU Support,” European Union Politics, Vol. 12, No. 2 (2011), pp. 241-266.

20. Niedermayer and Westle, “A Typology of Orientations.”

21. Inglehart, The Silent Revolution.

22. Niedermayer and Westle, “A Typology of Orientations,” p. 50.

23. For a review of these early studies, see: Özgehan Şenyuva, “Turkish Public Opinion and European Union Membership: the State of the Art in Public Opinion Studies in Turkey,” Perceptions,Vol. 11, (2006), pp. 19-32.

24. For examples: Ayşe Güneş-Ayata, “From Euro-scepticism to Turkey-scepticism: Changing Political Attitudes on the European Union in Turkey,” Journal of Southern Europe and the Balkans, Vol. 5, No. 2 (2003), pp. 205-222; Ayten Görgün, “What Turks Think of Europe?,” in Richard T. Griffiths and Durmuş Özdemir (eds.), Turkey and the EU Enlargement, (İstanbul: İstanbul Bilgi University, 2004), pp. 29-46.

25. For examples, Ali Çarkoğlu, “Who Wants Full Membership? Characteristics of Turkish Public Support for EU Membership,” Turkish Studies, Vol. 4, No. 1 (2003), pp. 171-194; Ali Çarkoğlu and Çiğdem Kentmen, “Diagnosing Trends and Determinants in Public Support for Turkey’s EU Membership,” South European Society and Politics, Vol. 16, No. 3 (2011), pp. 365-379; Michael F. Wuthrich, Murat M. Ardağ and Deniz Uğur, “Politics, Cultural Heterogeneity and Support for European Union Membership in Turkey,” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, Vol. 12, No. 1 (2012), pp. 45-62.

26. Hakan Samur and Behçet Oral, “Orientation of University Seniors from Southeastern Turkey to the European Union,” European Journal of Social Sciences, Vol. 5, No. 2 (2007), pp. 186-205.

27. Hakan Samur and Turgut Demirtepe, “Kürtlerin Avrupa Birliği’ne Yönelimi: Düşük Bilgi Düzeyi, Yüksek İdealist Beklentiler,” Uluslararası İlişkiler, Vol. 12, No. 48 (2016), pp. 55-76.

28. See, Turkish Statistical Institute Database, retrieved from http://www.tuik.gov.tr/

29. Bahar Başer, Diasporas and Homeland Conflict: A Comparative Perspective, (London: Routledge, 2015).

30. “Standard Eurobarometer 83: European Citizenship,” European Commission, (Spring, 2015), p. 83.

31. While 28 was the correct answer, respondents who said 27 were also included in this percentage.

32. “Standard Eurobarometer 85: Public Opinion in the European Union/Annex,” European Commission, (2016), p. 80.

33. “Standard Eurobarometer 85: Public Opinion in the European Union/Report,” European Commission, (2016), p. 72.

34. Respondents may simultaneously select one economic and one idealist expectation. As a result, the percentages here reflect not the number of people who hold utilitarian or idealist expectations, but the rate at which the expectations were repeated.

35. The 20 percent who said they would vote no in the referendum justified their choice mostly on the basis of utilitarian-economic reasons: Some 27 percent said economic resources would be handed over to foreigners, 17 percent said agriculture and small industry would suffer harm, 11 percent said unemployment would rise, 27 percent said national identity and culture would weaken, and 13 percent said national sovereignty would weaken; other responses and those who did not answer constitute 4 percent of the sample.

36. Burcu A. Bayram, “It’s the Economy, not European Identity: The Effect of European Identity and Economic Considerations on Public Support for EU Membership in Turkey and Central and Eastern European Countries,” Alternatives-Turkish Journal of International Relations, Vol. 14, No. 2 (2015), pp. 16-28.

37. Michael Keating, “The Minority Nations of Spain and European Integration: A New Framework for Autonomy?,” Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1 (2000), pp. 29-42; Richard Haesly, “Euroskeptics, Europhiles and Instrumental Europeans: European Attachment in Scotland and Wales,” European Union Politics, Vol. 2, No. 1 (2001), pp. 81-102.

38. Çarkoğlu, “Who Wants Full Membership? Characteristics of Turkish Public Support for EU Membership.”

39. Bahar Rumelili, Fuat Keyman and Bora Isyar, “Multilayered Citizenship in Extended European Orders: Kurds Acting as European Citizens,” Journal of Common Market Studies, Vol. 49, No. 6 (2011), pp. 1295-1316.

40. Ali Balcı, “The Kurdish Movement’s EU Policy in Turkey: An Analysis of a Dissident Ethnic Bloc’s Foreign Policy,” Ethnicities, Vol. 15, No. 1 (2015), pp. 72-91.

41. Kemal Kirişçi, “The Kurdish Issue in Turkey: Limits of European Union Reform,” South European Society and Politics, Vol. 16, No. 2 (2009), p. 342.

42. Thomas Risse, “Social Constructivism and European Integration,” in Antje Wiener and Thomas Diez (eds.), European Integration Theory, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), p. 170.

43. See, Turkish Statistical Institute Database, retrieved from http://www.tuik.gov.tr/

44. Katinka Barysch, “What Europeans Think about Turkey and Why?,” Centre for European Reform Essays, (September 25, 2007), retrieved May 20, 2016, from https://www.cer.org.uk/sites/