Introduction

The holy region, Islamicjerusalem (Bayt al-Maqdis), and the city at its heart –today known as Jerusalem (al-Quds)– has been significant from time immemorial: religiously, historically, and geopolitically. Following centuries of peace and harmony, amongst the three monotheistic religions during the Mamluk and Ottoman periods, the region has been in turmoil since December 1917 when British rule began, with no successful formula for the implementation of a fair coexistence, sustainable peace, and just stability. Many resolutions and peace initiatives were declared related to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict even before the Zionist state was established in 1948. Zionist occupation only increased the polarization of, and problems for, the region and its inhabitants. There are many resolutions declared by the United Nations that are accepted as the international law applying to the status quo of Jerusalem; the position of al-Aqsa Mosque and the holy places; the state of Palestine and the two-state solution; the borders drawn pre-1967; Israeli settlements; and the right of return for Palestinian refugees. But none could be implemented due to the Israeli occupation and the United States’ unequivocal support for Israel.

Undoubtedly, one of the most important factors that make the region important is al-Aqsa Mosque. To Muslims it is the first qiblah, the Second Mosque ever built on earth, and one of Islam’s three holiest places. Generally, access to mosques is solely for Muslim prayer, as is the case in churches and synagogues for their followers. While Makkah and Medina are exclusive, Islamicjerusalem is inclusive according to Islam, non-Muslims are permitted to move freely within the city, but this does not apply to Islam’s holiest site in the region, the al-Aqsa mosque. This was particularly so after the crusade in 1099, which desecrated the al-Aqsa Mosque over a period of eighty-eight years and turned the mosque’s structures into churches, residences, warehouse and stables. Following the Muslim liberation, and particularly during the Ottoman and Mamluk periods, non-Muslims were generally not allowed entry to al-Aqsa Mosque.1 When Muslims arrived in the holy city in the seventh century, the Mosque area had been empty for at least 500 years according to archaeological and historical accounts. This is evident in the Madaba mosaic map of the holy land, dating from before the Muslims conquered the holy city during the reign of Caliph Umar in 637CE.2 Even the Western Wall of al-Aqsa Mosque had no significance in Jewish practices until the Ottoman period. This was all due to change with the British and Zionist occupations.

After Israel occupied the city in June 1967, Jordan and Israel agreed that the Islamic Waqf would have control over the inside of the holy site, while Israel would control external security. Non-Muslims would be allowed onto the al-Aqsa Mosque compound during visiting hours but would not be allowed to pray in the compound. However, in recent years, many pro-Temple religious Zionists have increasingly entered the inner circle of Israeli political leadership and have tried to modify the status quo. The al-Aqsa Mosque constitutes a sixth of the old city, and symbolically it is at the heart of the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians. This was the case even during the British occupation of Palestine, where many revolts took place due to encroachment over parts of al-Aqsa Mosque, namely al-Buraq Wall.

President Erdoğan said that the plan disregards Palestinians’ rights and attempts to legitimize Israel’s occupation and that the plan proposing to leave Jerusalem to Israel is never acceptable

The 45th and current President of the United States of America and billionaire, Donald Trump, has declared a plan that he introduced as the ‘Middle East peace plan’ or the so-called ‘deal of the century’ with the Prime Minister of Israel, Benjamin Netanyahu, in the East Room of the White House on January 28, 2020. The Palestinians, the UN, the EU, the Arab League, and almost all other political actors in the world rejected and criticized the plan. This study aims to examine how al-Aqsa Mosque is defined in the plan and could the plan pave the way for full Israeli sovereignty and control over this Muslim holy site?

Trump’s Middle East ‘Peace’ Plan, The Deal of the Century

It must be noted that the Zionist client-state was created to serve Western interests in the region; the idea of it precedes Jewish Zionism and was the brainchild of Christian Zionism.3 This is enforced by United States politics, an example of which is the former U.S. Vice President Joe Biden making it clear that, “As many of you heard me say before, were there no Israel, America would have to invent one.”4 The first step Trump took was U.S. recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of the Israeli state on December 6, 2017.5 Although rejected by the majority of world leaders, the U.S. vetoed a motion in the United Nations Security Council, in which 14 out of its 15 members condemned Trump’s decision.6 Despite international objection, the U.S. went ahead, moving its embassy to Jerusalem on May 14, 2018.7 Following which, Trump presented on January 28, 2020 his Middle East peace plan as the ‘Deal of the Century’ in a 181-page document named “Peace to Prosperity, A Vision to Improve the Lives of the Palestinian and Israeli People,” promising to keep Jerusalem as Israel’s undivided capital. Palestinians were lured to accept this plan with a $50 billion new investment over 10 years with Arab Gulf money.8 As such, Israel and the U.S. are putting forward a unilateral plan deciding on the permanent status of Jerusalem and Palestine.

The Palestinian Authority and Palestinian political parties such as Hamas, as well as the UN, the EU, the Arab League, and almost all the rest of the political world, have rejected and criticized the plan. Whereas the United Arab Emirates, Egypt and Bahrain fully supported the plan in official statements, Saudi Arabia gave contradictory statements playing on both sides. This shows the extent of Arab States’ hypocrisy and negligence over the issue of Palestine in recent times. Turkey, on the other hand gave a clear, definitive, and sharp response against this plan. President Erdoğan said that the plan disregards Palestinians’ rights and attempts to legitimize Israel’s occupation and that the plan proposing to leave Jerusalem to Israel is never acceptable. Moreover, Turkey did not only give a written statement, it voiced the issue in international platforms.

While much of the current political discussions are focused on the plan’s annexation of the Jordan Valley and the West Bank, there is not enough discussion over the appropriation of al-Aqsa Mosque

Changing the Status-Quo of Jerusalem

Under international law, al-Quds/East Jerusalem, together with the West Bank are occupied territories since 1967 and from which Israel should withdraw, as established in many UN resolutions.9 However, Israel contends these readings and emphasizes that it possesses rights over these territories. One thing that Trump’s plan agrees with, and unequivocally suggests, is that a ‘united’ Jerusalem would be the eternal capital of Israel and would remain an undivided city. However, in doing so, it suggests that some part of the West Bank can be internationally accepted as the capital of a ‘future’ State of Palestine. There is an absurd point in the document about what and where al-Quds is. It is explained that the sovereign capital of the State of Palestine should be in a section of East Jerusalem located in the areas east and north of the existing separation barrier, including Kafr Aqab, the eastern part of Shuafat and Abu Dis, and “that could be called al-Quds or another name as determined by the State of Palestine.”10 The proposed Palestinian state would not include any part of the historic or political areas of Jerusalem falling within the current separation barrier, which contains the Old City and al-Aqsa Mosque and the areas where most East Jerusalemites live. The suggestion that another site, village or town can actually be given this centuries old name of al-Quds, shows how one-sided this plan is in its aim of appeasing the Israeli side with a reckless disregard and belittling of the Palestinians and Muslims. This is clearly changing the status quo and is a violation of international law.

According to this plan, ‘undivided Jerusalem’ including its places of worship and holy places, especially the al-Aqsa Mosque, will be under the sovereignty of Israel, giving it the task of safeguarding these holy sites and guaranteeing freedom of worship. Although it claims that the status quo is to be maintained, the plan rejects Palestinian sovereignty over al-Aqsa Mosque/ Haram al-Sharif. 11 While much of the current political discussions are focused on the plan’s annexation of the Jordan Valley and the West Bank, there is not enough discussion over the appropriation of al-Aqsa Mosque.

The “Old City” region of East Jerusalem, the occupied capital of Palestine, and the surrounding area of the city walls hosts cultural heritage important to many peoples, February 18, 2020. MOSTAFA ALKHAROUF / AA

The “Old City” region of East Jerusalem, the occupied capital of Palestine, and the surrounding area of the city walls hosts cultural heritage important to many peoples, February 18, 2020. MOSTAFA ALKHAROUF / AA

The Current Status of Al-Aqsa Mosque

Al-Aqsa Mosque with its ancient walls is a 35-acre (142,000m2) area of land in the eastern part of the Old City, known by some as al-Haram al-Sharif (the Noble Sanctuary). It houses hundreds of monuments built by Muslim rulers after the Muslim conquest in the seventh century, such as al-Jami’ al-Aqsa (with the silver-domed structure dating back to a small structure built by caliph Umar and later rebuilt during the Umayyad period), the Dome of the Rock (with its golden dome and also constructed by the Umayyads in the heart of the al-Aqsa Mosque), and the Dome of the Chain, amongst other structures. The Mosque’s compound has been the most disputed piece of territory in the Holy Land since Israel occupied eastern Jerusalem, including the Old City, in 1967, together with the West Bank and Gaza Strip. However, the conflict over it dates even further back, before the establishment of Israel, and particularly during the British occupation, during which Zionists aimed to control parts of the western wall of the al-Aqsa Mosque, namely, al-Buraq Wall.

For Muslims, the compound hosts one of Islam’s three holiest sites: the ancient al-Aqsa Mosque reconstructed in the seventh-century is considered to be the first qiblah (the place where Muslims turn to during their prayers) of Prophet Muhammad and the place from which he ascended to Heaven. Further, it is believed to have been one of two centers of monotheism from time immemorial, before Judaism and Christianity. Jews claim that it is the site where Biblical Jewish temples once stood, thus Jewish law and the Israeli Rabbinate forbid Jews from entering the compound and praying there as it is thought to be too holy to tread upon. Al-Aqsa Mosque’s Western Wall, known as the ‘Wailing Wall’ to Jews, is claimed to be the last remnant of the Second Temple without any historic or archaeological evidence, while Muslims refer to it as al-Buraq Wall and believe it is where the Prophet Muhammad tied al-Buraq.12 An International Commission investigated the issue of al-Buraq wall after the Buraq Uprising in 1929 and published its findings in 1930. The Report of the International Commission on al-Buraq/ Western Wall concluded that the ownership of the wall and the proprietary rights to it, belong solely to the Muslims and forms an integral part of the Haram al-Sharif area, which is Waqf property. The commission’s report was approved by the League of Nations in 1931. However, in June 1967, Israel took full control of al-Buraq Wall and destroyed the Maghariba Quarter adjacent to it with all its Waqf properties. There were also suggestions by the Israeli army’s chief rabbi, Shlomo Goren, to blow up the Dome of the Rock13 and destroy the area of al-Aqsa Mosque.

For Muslims, the compound hosts one of Islam’s three holiest sites: the ancient al-Aqsa Mosque reconstructed in the seventh-century is considered to be the first qiblah of Prophet Muhammad and the place from which he ascended to Heaven

Since 1967, non-Muslims, including Jews, were allowed entry to the site during visiting hours, but would not be allowed to pray there. However, a Jewish religious ban on entering the whole site of al-Aqsa Mosque was issued by the Chief Rabbinate of Israel and a sign was placed at the al-Aqsa’s southwestern entrance, the Maghariba Gate, warning that according to the Torah it is forbidden to enter the area. However, rising Temple movements, such as the Temple Mount Faithful and the Temple Institute, have challenged the religious ban on allowing Jews to enter the site of al-Aqsa Mosque, and challenged the Israeli government’s position on banning Jewish prayer inside the mosque. They have gone even further and proposed reconstructing a ‘Third Jewish Temple’ in the site. Such groups were on the fringe of Israeli society in the past, but today are backed by members of the Israeli government, though it ostensibly claims an ambition to maintain the status quo of the compound.14 Today, Israeli Occupation forces allow groups, some in the hundreds, of Jewish settlers who live in occupied Palestinian land, to storm the al-Aqsa compound under police and army protection, heightening Palestinian fears of an Israeli takeover of the compound.15

In 1990, the Temple Mount Faithful announced that it would put a cornerstone for the ‘Third Temple’ in place of the Dome of the Rock. This led to an uprising and a massacre in which 21 Palestinians were killed by Israeli occupation forces inside the mosque.16 In 2000, Israeli politician Ariel Sharon stormed the holy site accompanied by some 3,000 Israeli soldiers and police, intentionally repeating Israeli claims to the area in light of then-Prime Minister Ehud Barak’s U.S.-brokered negotiations with Palestinian president Yasser Arafat, which included discussions on how the two sides could share Jerusalem. Sharon’s entrance to the al-Aqsa Mosque compound set off the Second Intifada, in which more than 3,000 Palestinians and some 1,000 Israelis were killed.17 Today, Israeli soldiers and police enter al-Aqsa on a daily basis; they have even established a police station within the mosque since 1967 that is stationed at the Ottoman Janbulat Zawiyah, north of the Dome of the Rock.

Al-Aqsa Mosque Enclave in Trump’s Plan

The document, in its section on “Jerusalem’s Holy Sites,” starts by mentioning how Israel, after the Six Day War in 1967, took upon itself the responsibility of protecting all of the city’s holy sites and the document lists 31 of them, starting with the “Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif, the Western Wall.” The rest of the list is composed of 17 Christian sites and 13 supposedly Jewish ones and only mentions with regards to Islam, “the Muslim Holy Shrines,” without naming a single mosque or an Islamic monument from the hundreds of Islamic structures within the old city.18 This is besides listing and making up the names of Jewish sites which have no holiness in Judaism, as shown in a study by an Israeli NGO.19 It thus presents the city as being of Jewish character while undermining the real character of the city. Even the wording “Temple Mount,” followed by “Haram al-Sharif,” clearly suggests the narrative being presented. The document then commends Israel for doing what previous rulers have not done: “Unlike many previous powers that had ruled Jerusalem, and had destroyed the holy sites of other faiths, the State of Israel is to be commended for safeguarding the religious sites of all and maintaining a religious status quo.”20 Immediate previous powers include the Jordanian, British, Ottomans and Mamluks and for over a millennium of Muslim sovereignty, no destruction of churches or synagogues took place.21 In reality, it is factually established that after the Zionist occupation in 1967, Israel had, in the first few days, destroyed next to al-Buraq Wall two mosques, a Zawiyah and a Madrasah, together with the whole of the Magaribah Quarter in an archaeological crime. 22 The biased narrative is clear from the outset of the document. This section will try to delve into the position and future of al-Aqsa Mosque according to this plan.

Significance of the Site of Al-Aqsa in the Plan

The name ‘al-Aqsa Mosque’ is mentioned only twice in the document, once in quoting Quran 17:1 regarding the Night Journey. The second is in reference to one of al-Aqsa Mosque’s structures, al-Jami al-Aqsa (with the silver dome), in relation to Israeli tolerance, stating that: “Each day, Jews pray at the Western Wall, Muslims pray at the al-Aqsa Mosque and Christians worship at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.”23 This reduced the meaning of al-Aqsa Mosque to one single building within the Mosque’s compound, as is apparent from the use of the term Haram al-Sharif together with Temple Mount for the whole compound. However, it is known that the whole of the 35-acre walled area is holy for Muslims and all of it is regarded as part of al-Aqsa Mosque. 24 In a status report presented to the UNESCO by Jordan and Palestine, it is stressed that “al-Aqsa Mosque” and “al-Haram al-Sharif” are identical terms and defines it as constituting “144 Dunums (= 144,000 m² - with lengths of 491 m west, 462 m east, 310 m north and 281 m south).”25

In the document, the whole area of al-Aqsa mosque is named “Temple Mount/ Haram al-Sharif.” Historically, the term al-Haram al-Sharif was first used to refer to the whole of the al-Aqsa area during the Ayyubid period after it was regained from the crusades. This was to emphasize the sacredness of the whole area.26 The term continued to be used during the subsequent Mamluk and Ottoman periods and until the mid-19th century, non-Muslims were not permitted into the mosque’s compound. The first known exception was made by order of the Ottoman Sultan in 1862, during the visit of the Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII.27

The text of the plan describes the importance of the al-Aqsa Mosque in terms of the 3 religions. Obviously, it starts with the Jewish connection with this site. The document clearly takes the official Israeli perspective on the issue of the importance of Jerusalem and al-Aqsa to Jews and presents it as fact. The focus of the text is on the area it contends as constituting the site of al-Aqsa Mosque compound. It starts with the biblical name “Mount Moriah” and makes the link to the Biblical Abraham, implying that he is the start of the Jewish connection, although Judaism was not founded for another half a millennium. It then gives the narrative of the first and second temples and stresses that it is the holiest site for Judaism.28 Such narrative is based on unfounded ideas, disputed even by Israeli Jewish archaeologists as fiction. The text tries clearly to present that Jews are connected with this site and always yearned for it. As for Christianity, the document does not make any link with the site of al-Aqsa Mosque whatsoever, yet stresses the Christian importance of the city and its churches. When it comes to the Islamic connection, it starts with quoting Quran 17:1, that it was the qiblah only for a short period in Madinah, and then moves to questioning the importance of al-Aqsa Mosque to Muslims.29 Whereas it tries to show that it is the Holiest site for Judaism, it states that it is ‘only’ the third holiest site in Islam. This inaccurate proposition is an attempt to undermine the importance of the site to Muslims. In actual fact, it is one of Islam’s three holiest sites and the argument that it is the third is to implicitly push the idea that it is the holiest place for Judaism. The text then moves into presenting an Orientalist argument that it became an alternative Hajj center as part of Muslim rivalry. This view has not been seen as historically acceptable, since pilgrims from Syria continued to make pilgrimage during the Umayyad period, and Caliph Abd al-Malik bin Marwan who built the Dome of the Rock, also visited Makkah for the pilgrimage.30 This disregarded view was presented in the text as a view shared and accepted by the Muslim world.

In reality, two billion Muslims were restricted access to their holy site, whereas prior to the Zionist occupation, Muslims would visit it from the four corners of earth

The Position and Future of Al-Aqsa in the Plan

The text of Trump’s plan claims rights to al-Aqsa Mosque in line with the Zionist project and the Jewish narrative, which is clear in the text of the document. While sometimes trying to sound objective, the rest of the text reveals the real intentions of the plan. At the outset, it states that this is a very sensitive matter but moves onto pay lip service and claims that Israel has kept Jerusalem open and secure and it should remain open to all.31 In reality, two billion Muslims were restricted access to their holy site, whereas prior to the Zionist occupation, Muslims would visit it from the four corners of earth. Discussion on the inclusiveness of Jerusalem is, in theory, applaudable and is something that is accepted Islamically, but in practice this has not been the case. It pushes the idea of a ‘united Jerusalem’ with one single sovereignty together with inclusivity, but given Israel’s track record on freedom of worship for Muslims and Christians, this is clearly not the case.

This approach is of direct importance to the position of al-Aqsa Mosque in the plan and raises the questions of how it can be accessible to all in a manner that is respectful to all. The issue here is the contested holiness of an already existing Mosque: Of how Israel can respect the holiness of the Mosque when it encroaches upon it. Although calling for the continuation of the same governance regimes that exist today and the maintaining of the status quo over al-Aqsa Mosque compound, in practice the plan is suggesting a major change to this. The site of the al-Aqsa Mosque, referred to in the document as Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif, is currently supervised by Jordan’s Islamic Waqf following the 1967 War. According to an unwritten 1852 Ottoman-era regulation and system, known as the status quo, only Muslims can pray at the site, while non-Muslims are only allowed entry as visitors or tourists.32 This status quo has been tweaked a few times, with the occupation in 1967 and the loss of al-Buraq Wall and Israeli control over the gates of the mosque. The second change occurred in 2000, when Ariel Sharon stormed the mosque with over 1,000 soldiers. The third was with the order of Israeli officials of the exclusion of Muslim worshippers out of the mosque to make Jewish visitors more comfortable.33 The fourth is with the closure of al-Aqsa Mosque for two weeks in 2017 and the sealing off parts of the mosque from Muslim access. However, the plan suggests a major change in terms of full Israeli sovereignty, which would change the status quo entirely and would no longer be practicable.

The text is quite contradictory in that although it calls for the status quo to be maintained, it proposes in practice three main changes: it would “undo the centuries-old system completely: transferring the site to Israeli rule, rescinding Jordan’s custodianship over it and ending the ban on non-Muslim prayer.” This seems like an attempt to end Jordan’s Islamic Waqf administration and end Muslim control of the mosque compound, particularly since it describes Israel as a custodian of Jerusalem’s holy sites.34

The plan is disguised behind a benevolent vision of inclusivity and freedom of worship, but when it comes to the practicalities, it reveals the real intentions of changing the status quo. It calls for access to al-Aqsa Mosque for Jews, people of other faiths and the liberation of worship at the Holy site, stating:

Jerusalem’s holy sites should remain open and available for peaceful worshippers and tourists of all faiths. People of every faith should be permitted to pray on the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif, in a manner that is fully respectful to their religion, taking into account the times of each religion’s prayers and holidays, as well as other religious factors.35

Although initially trying to talk in general terms of all holy places, it specifies the al-Aqsa Mosque compound on this matter. There is no interest in Muslims or Christians praying in each other’s places of worship. The compound is mentioned only in terms of it being a place where Jews would like to officially commence prayer. The plan suggests that there ought to be independent worship at the mosque’s compound in an attempt to make a major change to the historical status quo, even as the document states that it should be maintained. It goes further in suggesting an Israeli proposition discussed in the Knesset of allowing different times for Jewish and Muslim worship, which would in turn mean separate times and spaces during religious holidays in particular. This would enforce and legitimize Israel’s changes to the status quo, particularly with regards to the temporal division of the mosque, and would give it the green light to cross the line into the spatial division.

For some years, Israel has progressively allowed and provided for Jewish prayer and forced greater limitations on the Waqf’s independence. Growing numbers of religious Jews have visited the al-Aqsa Mosque, many of whom are part of Temple movements. These activist groups are pushing for political support of Jewish prayer at the mosque, as well as full Israeli control over it, with the ultimate purpose of building a “Third Temple.” Temple activists have already been adopting the plan’s language to argue for doing away with the non-Muslim prayer ban. Students for “Temple Mount,” for example, initiated a media campaign within two days of the plan’s release, named “The Time Has Come: Sovereignty and Freedom of Worship at the Temple Mount for Jews Now!,” citing the Trump plan’s declaration in support of Jewish prayer.

The proportion of Israelis who identify themselves as religious Zionists is not more than 25 percent in Israel but they have become the pillar of the state of Israel and now represent the hegemony

David Friedman, the U.S. Ambassador to Israel, in trying to clarify the plan, said that no forced alteration of the current status quo over al-Aqsa Mosque would take place. In a special Briefing on January 29, 2020, he was asked if today’s status quo would change, and if Jews will be allowed to pray on the Sabbath, Christians on Sundays and Muslims on Friday, and in certain areas or even buildings created on the Mount for Jewish and Christian prayer beside the Muslim mosque? He started by acknowledging that some people have found the plan “contradictory to the status quo,” and he explained that, “the status quo, in the manner that it is observed today, will continue absent an agreement to the contrary.” Thus, any change would only take place after an agreement of all the parties.36 His explanations claim that no change would take place without agreement, yet the whole plan has no agreement from the Palestinian side, which has officially rejected it outright. His statement is rather vague as, “the status quo, in the manner that it is observed today” is not the historic status quo and is already deviating from the historical arrangement in both Jordanian and Palestinian eyes. Israel has substantially changed the status quo, and in fact, already allows low-profile Jewish prayer and imposes restrictions on Waqf activities inside the mosque.37 Thus, the “manner that it is observed today” would include all current Israeli changes and possibly future ones. Accordingly, Israel will want to achieve more on the ground before any negotiations commence with a new de facto situation on the ground.

Changes in Israeli Society over Al-Aqsa

The issue of building a Temple over al-Aqsa compound was considered taboo in Israeli society, and although many aspire to it, they await divine intervention. Yet with the occupation of the Holy City in 1967, the army’s chief rabbi, Shlomo Goren, wished to blow up al-Aqsa Mosque. An attempt was made by a Christian-Zionist in 1969, causing much damage to the mosque’s southern building, al-Jami al-Aqsa, but other attempts failed. Discussion of the issue was on the fringes of Israeli society only a few decades ago, and it was not discussed publically in political circles. Religious Zionism shied away from the issue until the past decade, but today it has become one of the most signiÞcant voices within that community.38 The rising Temple movements entering Israeli politics have now turned the discussion into mainstream debate.

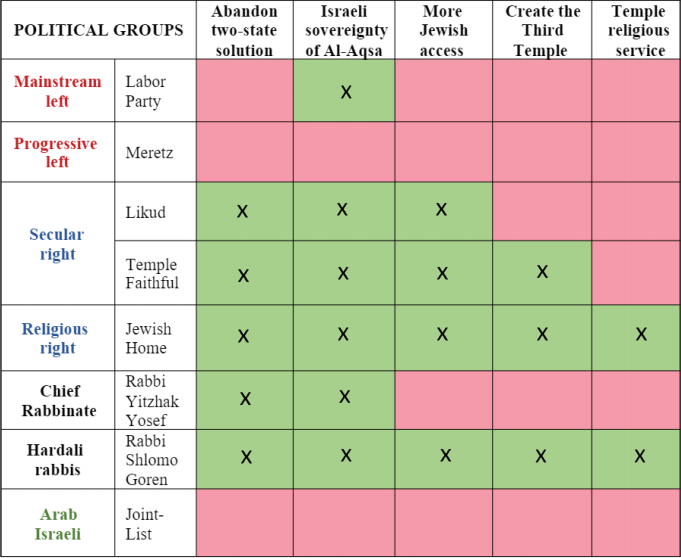

The proportion of Israelis who identify themselves as religious Zionists is not more than 25 percent in Israel39 but they have become the pillar of the state of Israel40 and now represent the hegemony.41 Many pro-Temple religious Zionists have actually entered the inner circle of Israeli political leadership. These people come from national-religious parties that are mighty allies of the ruling Likud. Former Minister of Construction, Uri Ariel, from the Jewish Home party, for instance, has on numerous occasions violated the status-quo by praying in the al-Aqsa Compound and stated his support for the creation of the Third Temple.42 Additionally, the Minister of Education, Rafi Peretz, made a statement that “the Temple Mount had no religious significance to Muslims.”43 Additionally, the then minister of Jerusalem and Diaspora Affairs, Naftali Bennett has made a suggestion in 2014 for the potential enhancement of Israeli sovereignty over al-Aqsa compound and broader Jewish access to it.44 Rabbi Yehuda Glick, an influential pro-Temple religious Zionist, often featuring in the news due to his controversial countless visits to the al-Aqsa site, has even become part of the Likud and a Member of the Knesset.45 Pro-Temple groups have gained considerable power in the Israeli government and Knesset in recent years. Judging by their comments in the news, their views are radical and indicate that they are willing to do everything to erect the so-called Third Temple. In a study on positions of Israel’s Political Groups on the al-Aqsa Compound, Lukman shows that the majority of Israeli parties maintain that the al-Aqsa Mosque Compound must become fully under the sovereignty of Israel. Only the progressive left and Arab-Israeli parties rejected any change to the status quo (see Table 1 below).

Table 1: The Positions of Israel’s Political Groups on the Al-Aqsa Compound

Although the Labor Party wishes for full Israeli sovereignty, it rejects the attempt to push for wider Jewish access to the al-Aqsa Mosque’s Compound, as does the Chief Rabbinate for religious reasons. This is because the ultra-Orthodox community is divided on this matter: the majority follow the Chief Rabbinate religious ruling that prohibits Jewish visit and prayer at the compound. Some Jewish Rabbis have even blamed Jews who enter al-Aqsa for the escalation of violence and in sparking more turmoil and that it is ‘strictly prohibited’ to enter the site. However, some circles of national Orthodox (Hardali/Hardalim) Rabbis who follow militant-messianic rabbis, such as Shlomo Goren, encourage visits and prayer at al-Aqsa Mosque.47 The Likud party, although pushing for full sovereignty and more access for Jews, does not go to the extent of supporting calls to build the Third Temple and stays detached on the issue, though some members do support it publically. However, the Temple Mount faithful,48 an established political movement, actively advocates for the building of the Temple.49 As can be seen from Table 1, the majority among Israeli parties from Right-wing parties, the ultra-Orthodox, as well as the mainstream left, seek full Israeli sovereignty over al-Aqsa Mosque Compound.

Palestinian Islamic Jihad Executive Khaled al-Batsh (2nd R), Hamas official Khalil al-Hayya (4th L), al-Fatah movement leader Imad al-Agha (4th R) and representatives of other groups attend a meeting organized to determine a joint national plan against Israel’s annexation plan in Gaza City, on June 28, 2020.MUSTAFA HASSONA / AA

Palestinian Islamic Jihad Executive Khaled al-Batsh (2nd R), Hamas official Khalil al-Hayya (4th L), al-Fatah movement leader Imad al-Agha (4th R) and representatives of other groups attend a meeting organized to determine a joint national plan against Israel’s annexation plan in Gaza City, on June 28, 2020.MUSTAFA HASSONA / AA

Latest Changes

Israel has publicly stated that it upholds the status quo, and Trump’s plan suggests the same, yet it also proposes for a temporal division of al-Aqsa Mosque which Israel had already been applying, even before Trump’s announcement of his plan. The Mosque’s compound would thus become a shared place for prayer. In the current arrangement, Israeli occupation forces would restrict Muslim access in the morning (7:30 a.m. to 11:30 a.m.) and during another time slot in the afternoon, throughout which they would allow Jewish settlers entry to the mosque. Ostensibly, there is a ban on Jewish prayer inside the Mosque, however, in practice, this prohibition is no longer enforced. Israeli police have allowed low-profile prayer as well as discreet study of religious texts and the conducting of rites of passage, while restricting open and loud prayers to some extent. Gilad Erdan, Public Security Minister, who is responsible for police policies at al-Aqsa Mosque, echoed this publicly and has openly encouraged ongoing Jewish prayer. He is quoted to have said at numerous occasions as follows:

The status quo on the Temple Mount since 1967 is unjust, and this injustice should be corrected so that Jews will not only be able to visit the Mount, but also to pray there. The Temple Mount is the holiest site for the Jewish people, while it is only the third-holiest site for Muslims. It is imperative to act so as to allow Jews to pray there as well, but this should be achieved by means of political arrangements, rather than by force.50

Trump’s plan and the clarification of Ambassador Friedman echo Erdan’s wordings. While stating that change should be through political agreement, Erdan is already enforcing changes on the ground without agreement.

Israel has recently increased the number of deportation orders banning influential Muslim figures from entering al-Aqsa Mosque, including the Imam of al-Aqsa Mosque, Shaikh Ikrime Sa’eed Sabri

New developments are playing on the contradictory articles of Trump’s plan, in which the status quo should be maintained, while at the same time Jewish prayer and access should be granted. Israel is already altering current arrangements and enforcing its interpretation with new facts on the ground in fulfilling Israeli sovereignty over the site. Currently, Muslims within the mosque compound are forcefully being confined to the closed buildings of al-Aqsa Mosque during the storming of settlers or are even kicked out of the mosque or imprisoned. Previously, Muslims would pursue the settlers around the mosque and try to emphasize the Muslim presence through raising their voices with takbir (chanting “God is Great”), but this is no longer possible and anyone attempting to confront the settlers will be arrested and issued with a ban from entering the mosque as they are not ‘peaceful worshippers.’ In addition, the role of the Islamic Waqf is being restrained, with Muslim guards not being allowed to accompany settlers or film them while conducting religious rituals or committing aggression inside the mosque. This would open the way for full Jewish services inside the mosque by clearing the path of the settlers from Muslim guards and worshippers who were seen as the hurdle in implanting this. Thus, Israel has recently increased the number of deportation orders banning influential Muslim figures from entering al-Aqsa Mosque, including the Imam of al-Aqsa Mosque, Shaikh Ikrime Sa’eed Sabri.

Israeli forces have also stepped up their attempts to prevent the Waqf Authority from carrying out any renovation or restoration on the Mosque compound or structures, arresting the director of Reconstruction Committee at al-Aqsa Mosque, Bassam al-Hallaq, numerous times, in an attempt to endorse full Israeli sovereignty over the mosque. Israel has also started encroaching on the role of the Waqf in the restoration of the site, such as the external walls, particularly the southern western wall. Recently it has been revealed that Israeli authorities are using the cover of renovation to make physical changes inside the underground level of the mosque, an issue reported to UNESCO, which was prevented from investigating the matter.51 In addition, it has installed loud speakers on the external walls of the mosque in August and September 2020 without an agreement with the Waqf authorities. These actions are clearly limiting the work of the Waqf to administrating the Muslim presence in the mosque and restricting its other duties.

Israel has also capitalized on the closure of al-Aqsa Mosque during the COVID-19 pandemic (March to May 2020) to enforce even further changes on the ground

Besides the interference in renovation works and the temporal division, there are clear moves for the spatial partition of the mosque, similar to the spatial division of the Ibrahimi Mosque in Hebron. The Israeli authorities have pushed for the banning of Muslims from certain parts of the al-Aqsa Mosque’s compound, such as the area of Bab al-Rahma, in the eastern part of the mosque, which was opened by force by Muslim worshippers in September 2019, after Israeli forces had sealed it off for over a decade. However, Israeli forces have repeatedly arrested a number of Muslims from its vicinity in a repeated attempt to seal off this area to Muslims. This corresponds with an increase of settler movement in that area, with some settlers performing full prostration as part of prayer rituals in the eastern part of the mosque. The matter was also pushed politically and then transferred to an Israeli court, which issued a ruling on the closure of the building of Bab al-Rahma in July 2020.

Israel has also capitalized on the closure of al-Aqsa Mosque during the COVID-19 pandemic (March to May 2020) to enforce even further changes on the ground. The opening of the al-Aqsa Mosque’s compound for Muslim worshippers was on the same day as it opened for Jewish settlers. Although Muslims wanted this to be on a Friday, Israeli forces insisted on Sunday giving the idea of an equal footing for both sides. This, together with clearing the settlers’ path of any Muslims and allowing them to perform rituals, is fully ending the status quo over al-Aqsa Mosque. It also paves the way for new arrangements for a single sovereignty and shared custodianship meaning the Waqf authorities will be changed or limited to looking after the affairs of Muslim worshippers, while a similar Israeli body will do the same for Jewish worshippers. All of which seems to correspond with the ideas presented in the text of the plan, of allowing “People of every faith [to] be permitted to pray on the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif” and giving full Israeli sovereignty over al-Aqsa Mosque enclave.

The complicity of some Arab and Muslim states such as UAE and Bahrain in acknowledging and partaking in Trump’s deal has progressed the issue further. Both named countries have recently announced the normalization with Israel in August and September 2020 and in the joint statement released by the White House, there is a direct mention of al-Aqsa Mosque. The framework being Trump’s Deal of the Century, where al-Aqsa Mosque is reduced to a single structure of the mosque’s compound and stressing that all “other holy sites should/will remain open for peaceful worshippers of all faiths.”52 Whether these countries are consciously agreeing to weaver much of the al-Aqsa Mosque to Israeli sovereignty or are being played by the semantics is rather vague at this stage. Conversely, the position of Palestinians on the matter is unequivocal; the Islamic Supreme Council in Bayt al-Maqdis headed by Shaikh Ikrime Sabri have issued a number of statements condemning all Israeli actions and Trump’s plan and Arab states’ normalization deals. Additionally, in the latest encroachment on Bab al-Rahma, the council stated that it is an integral part of al-Aqsa Mosque and warned of the dangers of turning it into a synagogue. There are many reasons for refusing to approve of the plan to Palestinians and Muslims at large, not least its departure from international norms and law and its apparent bias. Such actions over al-Aqsa Mosque and the possibility of dedicating one or more of its buildings, such as Bab al-Rahma, for Jewish prayer will not only put an end to the already fragile ‘status quo’ but will start an international conflict over al-Aqsa which could easily turn into a religious war.

Conclusion

The new U.S plan to ‘resolve’ the conflict seems to only exasperate it further and sparks a new wave of conflict in Palestine and the region as a whole. Besides violating international law over Jerusalem, it encroaches on a very sensitive issue to billions of Muslims around the world, namely al-Aqsa Mosque, and any change to its status will surely have serious implications. Trump’s plan, although supported by some Arab countries, not only undermines the importance of al-Aqsa Mosque to Muslims, it also adopts the Zionist point of view fully. Its text clearly suggests that it was written based on the Israeli narrative as it applauses Israel for its good custodianship of holy sites, contrary to reality. It goes even further to invent new Jewish holy sites in the city which have no holiness in Judaism. The use of terminology in the document also has a clear role in portraying the Zionist view. Besides suggesting the reduction of the name al-Quds to a single village outside it, it reduces the area of al-Aqsa Mosque from the whole compound which can accommodate hundreds of thousands of Muslims, to the silver-domed structure, al-Jami al-Aqsa, which can accommodate 3,000-5,000 worshippers. In the document, the whole of al-Aqsa Mosque’s walled area is termed “Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif” and is portrayed as more significant for Jews, and should be open for all, but in practice it aims to change the status quo, all the while claiming otherwise. The document downplays the importance of al-Aqsa in Islam to a political struggle between Muslim rulers in the seventh century, thus pushing the Zionist idea that the holy compound is not that important religiously to Muslims. It has been demonstrated that the inclusion of such weak and extreme claims to undermine the importance of the al-Aqsa Mosque in Islam reveals the underlying aims of the plan for the whole area of al-Aqsa Mosque.

Trump’s plan, although supported by some Arab countries, not only undermines the importance of al-Aqsa Mosque to Muslims, it also adopts the Zionist point of view fully

The plan disguised behind an inclusive vision in calling for freedom of worship, but is rather contradictory on the issue of holy sites and particularly on al-Aqsa Mosque. In effect, it would alter entirely the status quo over al-Aqsa Mosque through three main changes: revoking Jordan’s administration of the Mosque, giving full Israeli sovereignty, and terminating the ban on non-Muslim prayer inside the mosque’s compound. The White House document calls for the ‘freedom’ of all worshippers and makes the establishment of a Jewish prayer area in al-Aqsa Mosque the initial step. Secondly, the plan would pave the way for full Israeli control of the Muslim holy site, and the implementation of a temporal and spatial division. This would mean, as suggested in the document, taking into account the times of each religion’s prayers and holidays, and may lead to the area of al-Aqsa being open only to Jews during Jewish religious holidays. If these two tactics are implemented, then this could lead to the changing of the function of al-Aqsa Mosque into a Jewish Place of worship. Israel has substantially changed the status quo since its occupation of the city in 1967 and continues to create a new de facto situation on the ground capitalizing on the lesser Muslim presence due to COVID-19 pandemic policies and the complicity of some Arab states. Finally, the increase in the number and representation rates of the pro-Third Temple religious Zionists in the Israeli government and Knesset, has brought this discussion into the mainstream of Israeli society after being on the fringes for decades. This besides creating an unanimity in calls for full Israeli sovereignty over al-Aqsa Mosque has reignited calls for the building of a Jewish Temple over the site of the Mosque. The full backing of the United States and the announcements of Trump’s plan can be considered as a step towards turning this dream to reality and raises the stakes for the destruction of al-Aqsa Mosque and the building of a Jewish Temple in its place.

Endnotes

1. Moshe Ma’oz, “The Role of the Temple Mount / Al-Haram Al-Sharif in the Deterioration of Muslim–Jewish Relations.” Approaching Religion, Vol. 4, No. 2 (December 2014), pp. 60-70.

2. Ian W. J. Hopkins, “The Old City of Jerusalem: Aspects of the Development of a Religious Centre,” Doctoral dissertation, Durham University, (1969), retrieved from http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/8763; Haitham al-Ratrout, The Architectural Development of Al Aqsa Mosque in the Early Islamic Period: Sacred Architecture in the Shape of the ‘Holy’, (Dundee: Al-Maktoum Institute Academic Press, 2004), p. 70.

3. Khalid El-Awaisi, “The Origins of the Idea of Establishing a “Zionist Client-State” in Islamicjerusalem,” Journal of Al-Tamaddun, 14, No. 1/2, (June 2019), retrieved from http://www.myjurnal.my/filebank/published_article/85882/2.pdf, pp. 13-26.

4. “Remarks by Vice President Joe Biden the 67th Annual Israeli Independence Day Celebration,” The White House, (April 23, 2015), retrieved from https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2015/04/23/remarks-vice-president-joe-biden-67th-annual-israeli-independence-day-ce.

5. “Presidential Proclamation Recognizing Jerusalem as the Capital of the State of Israel and Relocating the United States Embassy to Israel to Jerusalem,” The White House, (December 6, 2017), retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/presidential-proclamation-recognizing-jerusalem-capital-state-israel-relocating-united-states-embassy-israel-jerusalem/.

6. Victor Kattan, “Why U.S. Recognition of Jerusalem Could Be Contrary to International Law,” Journal of Palestine Studies, 47, No. 3, (2018), retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1525/jps.2018.47.3.72, pp. 72-92.

7. Abd al-Fattah El-Awaisi and Muhittin Ataman, Al-Quds: History Religion and Politics, (Ankara: SETA, 2019).

8. Jibrin Ubale Yahaya, “President Trump Peace Strategy: Emerging Conflict Between Israel and Palestine,” International Affairs and Global Strategy, 82, (2020), pp. 25-37.

9. Rashid Khalidi, “The Future of Arab Jerusalem,” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 19, No. 2, (1992), retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13530199208705557, pp. 133-143; Berdal Aral, “Oslo ‘Peace Process’ as a Rebuttal of Palestinian Self-Determination, ” Ortadoğu Etütleri, Vol. 10, No. 1, (2018), retrieved from https://orsam.org.tr/tr/oslo-peace-process-as-a-rebuttal-of-palestinian-self-determination/, pp. 7-26.

10. “Peace to Prosperity: A Vision to Improve the Lives of Palestinian and Israeli People,” The White House, (January 28, 2020), retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Peace-to-Prosperity-0120.pdf.

11. Yahaya, “President Trump Peace Strategy: Emerging Conflict between Israel and Palestine,” p. 28.

12. According to the Islamic belief, Buraq is the name of the mount/horse that Prophet Muhammed used to ascend to Heaven. Although such a name is not mentioned in the Quran, it is stated that there is such a presence in hadith

13. Nur Masalha, The Bible and Zionism: Invented Traditions, Archaeology and Post-Colonialism in Palestine- Israel, (London: Zed Books, 2007), p. 79.

14. Tomer Persico, “The End Point of Zionism Ethnocentrism and the Temple Mount,” Israel Studies Review, Vol. 32, No. 1, (2017), retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330661311_The_End_Point_of_Zionism_Ethnocentrism_and_the_Temple_Mount, pp. 104-122.

15. Wendy Pullan, “Bible and Gun: Militarism in Jerusalem’s Holy Places,” Space and Polity, Vol. 17, No. 3, (2013), retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13562576.2013.853490, pp. 335-356.

16. Motti Inbari, Jewish Fundamentalism and the Temple Mount: Who Will Build the Third Temple?, (New York: SUNNY Press, 2009).

17. “Al-Aqsa Mosque: Five Things You Need to Know,” Al-Jazeera, (December 6, 2017), retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2017/07/al-aqsa-170719122538219.html.

18. Walid Salim, “Al-Ma‘alim wal-Amakin al-Muqadasah fi al-Quds, Nadhrah Amaah,” al-Maqdisiyah, Vol. 2, No. 6 (Spring 2020), pp. 57-63.

19. Emek Shaveh, “The Sanctification of Antiquity Sites in the Jerusalem Section of the ‘Peace to Prosperity’ Plan,” (February 4, 2020), retrieved from https://alt-arch.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Sanctification-of-antiquity-sites-in-the-Jerusalem-section-of-the-%E2%80%98Peace-to-Prosperity%E2%80%99-plan.pdf.

20. “Peace to Prosperity,” p. 16.

21. What is being implicitly referred to here is the destruction of some synagogues in East Jerusalem under Jordanian rule, as Israel destroyed tens of Mosques or transferred their function in the areas under its control.

22. Oleg Grabar and Benjamin Kedar, Where Heaven and Earth Meet: Jerusalem’s Sacred Esplanade, (University of Texas Press, 2010).

23. “Peace to Prosperity,” p. 14.

24. Khalid El-Awaisi, Geographical Dimensions of Islamicjerusalem, (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2008). As for Muslims, the holy place of worship al-Aqsa Mosque covers the entire walled area, which includes the hundreds of historical monuments and buildings belonging to Muslims in this compound. The buildings’ roots extend for hundreds of years and the foundation of the mosque dates back even further in history.

25. “The State of Conservation of the Old City of Jerusalem and Its Walls,” UNESCO World Heritage Centre, (April 4, 2016), retrieved from https://whc.unesco.org/en/soc/3342.

26. Haram means, “forbidden, protected, untouchable” in the Arabic language and it is stated in the Qur’an that only Makkah (Qur’an: 9/28) and in the Hadith, Madinah are forbidden cities. Thus, some Muslim scholars have refused to use the term Haram for al-Aqsa Mosque, and insisted on the use al-Aqsa Mosque for the whole area. Yet, the reason for using the definition of Haram is so that non-Muslims do not enter al-Aqsa Mosque (al-Haram al-Sharif), where an inscription was placed above one of the entrances declaring the premises forbidden to non-Muslims, namely Christians. For more see, Sabri Jarrar, “Suq Al-Ma’rifa: An Ayyubid Hanbalite Shrine in al-Haram al-Sharif,” Muqarnas, 15, (1998), retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/i267862#aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuanN0b3Iub3JnL3N0YWJsZS9wZGZwbHVzLzEwLjIzMDcvMTUyMzI3Mi5wZGZAQEAw, pp. 71-100.

27. Hillel Cohen, “The Temple Mount/al-Aqsa in Zionist and Palestinian National Consciousness: A Comparative View,” Israel Studies Review, Vol. 32, No. 1, (Summer 2017), retrieved from https://www.berghahnjournals.com/view/journals/israel-studies-review/32/1/isr320102.xml, pp.1-19.

28. “Peace to Prosperity,” p. 15.

29. “Peace to Prosperity,” p. 14.

30. Anwarul Islam and Zaid al-Hamad, “The Dome of the Rock: Origin of its Octagonal Plan,” Palestine Exploration Quarterly, Vol. 139, No. 2 (2007), pp. 109-128.

31. “Peace to Prosperity” p. 9.

32. Ofer Zalzberg, “The Trump Plan Threatens the Status Quo at the Temple Mount/al-Haram al-Sharif,” Palestine-Israel Journal of Politics, Economics and Culture, Vol. 25 No.1 and 2 (2020), pp. 129-133.

33. Marian Houk, “Dangerous Grounds at al-Haram al-Sharif: The Threats to the Status Quo,” Jerusalem Quarterly, Vol. 63, (2015), pp. 105-119.

34. Zalzberg, “The Trump Plan Threatens the Status Quo at the Temple Mount/al-Haram al-Sharif,” p. 129.

35. “Peace to Prosperity,” p. 16.

36. Retrieved U.S. Department of State, (January 29, 2020), “Special Briefing via Telephone with Ambassador Friedman, Mr. Brian Hook, and Mr. Avi Berkowitz,” from https://www.state.gov/special-briefing-via-telephone-with-ambassador-friedman-mr-brian-hook-and-mr-avi-berkowitz/.

37. Zalzberg, “The Trump Plan Threatens the Status Quo at the Temple Mount/al-Haram al-Sharif.”

38. Persico, “The End Point of Zionism Ethnocentrism and the Temple Mount.”

39. Yair Ettinger, Privatizing Religion: The Transformation of Israel’s Religious Zionist Community, (Washington: Brookings Institution, 2017).

40. Ilanit Chernick, “Religious Affairs: How Did Religious Zionism Become a Pillar of Israel?,” The Jerusalem Post, (July 5, 2019), retrieved from https://www.jpost.com/opinion/religious-affairs-how-did-religious-zionism-become-a-pillar-of-israel-594669.

41. Yoav Peled, “Toward Religious Zionist Hegemony in Israel,” Middle East Report, 292, No. 3 (Fall/Winter 2019).

42. Houk, “Dangerous Grounds at al-Haram al-Sharif: The Threats to the Status Quo.”

43. Allison Kaplan Sommer, “Drawing Fire for Gay Conversion Comments, ‘Rabbi Rafi’ Doesn’t Look Moderate Anymore,” Haaretz, (July 14, 2019), retrieved from https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-meet-rabbi-rafi-the-israeliminister-at-the-center-of-the-gay-conversion-storm-1.7500007.

44. Judy Maltz, “Bennett: Temple Mount Part of Plan for Greater Israeli Sovereignty in East Jerusalem,” Haaretz, (February 17, 2014), retrieved from https://www.haaretz.com/.premium-bennett-temple-mount-is-israel-s-1.5323151.

45. Shlomo Fischer, “From Yehuda Etzion to Yehuda Glick: From Redemptive Revolution to Human Rights on the Temple Mount,” Israel Studies Review, Vol. 32, No. 1 (2017), pp. 67-87.

46. Gilang Lukman, “Positions of Israel’s Political Groups on the Al-Aqsa Compound: A Mapping of Doctrine and Policy,” Master of Philosophy candidate in Modern Middle Eastern Studies University of Oxford. Submitted in participation of Raid Salah International Award.

47. Rabbi Shlomo Goren was the army’s chief rabbi and later became the Chief Rabbi of Israel, had suggested the blowing up of al-Aqsa Mosque in 1967 and blew the Shofar (a religious ritual) at al-Buraq Wall and inside al-Aqsa Mosque. He also led the first Jewish prayer at al-Aqsa after its occupation.

48. Religious Zionists actively prepare for the constitution of the Third Temple, arguing that so long as the Temple is absent; their religious responsibilities cannot be entirely fulfilled. Proving their commitment, they have declared that a red heifer has already been prepared for the usage of ritual clarification prior to religious service in the Temple.

49. Lukman, “Positions of Israel’s Political Groups on the Al-Aqsa Compound: A Mapping of Doctrine and Policy,” p. 34.

50. Nadav Shragai, “Jerusalem’s best-kept secret comes in form of silent prayer,” Israel Hayom, (February 21, 2020), retrieved from https://www.israelhayom.com/2020/02/21/jerusalems-best-kept-secret-comes-in-form-of-silent-prayer.

51. Juman Abu Arafa, “That Gita’ al-Tarmim.. al-Ihtilal yakhtariq Sur al-Aqsa al-Gharbi, Al Jazeera, (July

17, 2020), retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.net/news/alquds/2020/7/17/%D8%AA%D8%AD%D8%AA%D8%BA%D8%B7%D8%A7%D8%A1%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AA%D8%B1%D9%85%D9%8A%D9%85%D9%81%D8%AA%D8%AD%D8%A%D8%AA%D9%81%D9%8A%D8%B3%D9%88%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D9%82%D8%B5%D9%89.

52. “Joint Statement of the United States, the State of Israel, and the United Arab Emirates,” The White House, (August 13, 2020), retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/joint-statement-united-states-state-israel-united-arab-emirates; “Joint Statement of the United States, the Kingdom of Bahrain, and the State of Israel,” S. Embassy in Israel, (September 11, 2020), retrieved from https://il.usembassy.gov/joint-statement-of-the-united-states-the-kingdom-of-bahrain-and-the-state-of-israel-2.