Introduction

Migration is the movement of individuals or communities from their settlements of origin across borders or within the state in which they live. In migratory population movements, individuals are displaced for various yet significant amounts of time, through the involvement of different structural factors, and for different reasons.2 People migrate from one place to another, either compulsorily or voluntarily, for reasons such as war, epidemics, natural disasters, economic problems, or the search for better living conditions, jobs, or educational opportunities. It can be modern or primitive, forced or free, small-scale or massive.3

Turkey hosts a large number of immigrant communities with different ethnic and linguistic backgrounds and provides public education services for them. One of them is the Meskhetian Turks, who have historical and cultural ties with Turkish society. The migration of Meskhetian Turks to Turkey can be examined in two different periods: The first is the period when Meskhetian came under the domination of Russia in 1829, and the second extends from the dissolution of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) in 1991 to the present day.4 As a result of these political developments, Meskhetian Turks took refuge in Turkey in groups at different times. In recent years, the Meskhetian people came to Turkey freely, so they were accorded the status of irregular migrants who seek to obtain residence and work permits according to the rights granted to the descendants of the same lineage. The number of Meskhetian Turks who obtained Turkish citizenship exceeded 40,000 in 2019. Many Meskhetian people have been settled in Turkey in urban areas such as Ağrı, Ankara, Antalya, Ardahan, Artvin, Aydın (İncirliova), Bursa (İnegöl), Çanakkale, Çorum, Denizli, Erzincan (Üzümlü), Erzurum, Hatay, Iğdır, İstanbul, İzmir, Kayseri, Muş, and Samsun.5

One of the groups that have the most difficulties with the immigration phenomenon are students because they are separated from their friends and teachers, and all that they have known. In some cases, the challenge of coping with these massive changes can cause a psychological breakdown. In addition to potential breakdown and depression, students often experience adjustment problems in education due to inequalities in the education system, language differences, and the need to change gears and take different courses.6

When the experiences of different immigrant groups are taken into account, we can better understand the attitude of the education system towards immigrants

The issue of education is one of the problems that immigrant communities face in their new home. In recent years, the issue of migration and education in Turkey has naturally been handled through the problems experienced by Syrians. When the experiences of different immigrant groups are taken into account, we can better understand the attitude of the education system towards immigrants. There are various studies on Meskhetian Turks in the literature and according to data obtained from these studies Meskhetian Turks, like other migrant populations, experience the negative effects of migration on education.7

Many students from different ethnic origins are included in the Turkish social and educational system. Understanding them and developing proper immigrant education policies will only be possible by getting to know them deeply. This study aims to provide insights into Turkish national education policies toward immigrant communities based on the experiences of Meskhetian Turkic high school students who migrated to Turkey. For this purpose, their cultural experiences, views about the differences in course and classroom practices, experiences due to bilingualism in the school and social environment, experiences in the school adjustment process, and lastly, their educational and cultural expectations are explored and interpreted.

Methodology

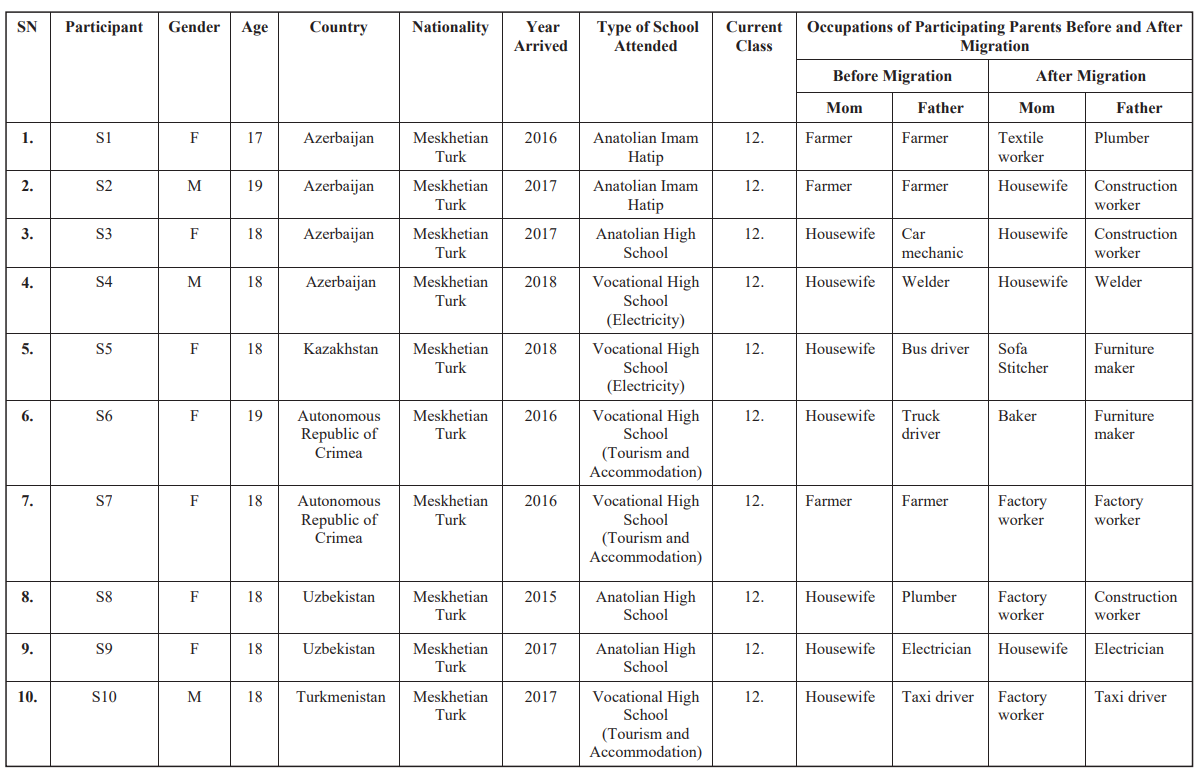

The qualitative research method of phenomenology, which focuses on individuals’ lived experiences, was used in the present study. Ten students who were continuing their secondary education in the 12th grade in İstanbul in the 2020-2021 academic year were selected as the study group. The 12th graders were interviewed because they have adequate Turkish language skills and plenty of experience in Turkish school settings. Interviews were conducted individually using online video conferences. Demographic information about the participants is included in the appendix. Interviews to determine the students’ experiences were carried out through a semi-structured interview technique. Descriptive and content analysis approaches were used in the analysis of the data. The data obtained from the interviews were arranged according to the research questions, then the data were analyzed and direct quotations were included when necessary.

Findings

The findings that reveal the educational and cultural experiences of Meskhetian Turkic secondary school students who migrated to Turkey were obtained via an analysis of the opinions obtained from the participants. Necessary codes were created in line with the participants’ opinions, and the codes obtained were combined under seven themes:

- Reasons for migration to Turkey,

- Cultural differences in Turkey according to the place of migration,

- Differences in classroom and classroom practices,

- Adaptation problems at school or in the social environment due to bilingualism,

- The experiences of the participants in the integration process to Turkey,

- Differences in education/cultural policies between Turkey and their home country in the context of the school environment,

- Evaluation of education in Turkey in terms of expectations and suggestions.

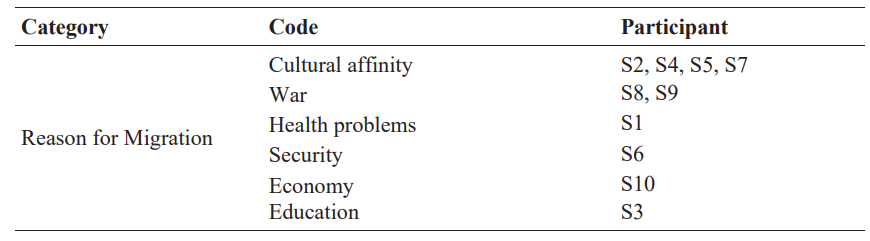

The most important factor in meeting the needs of immigrants appropriately and determining the social policies for them is the reasons for migration. The reasons for the participants’ emigration are given in Table 1.

Table 1. Reasons for Migration to Turkey

According to Table 1, it is seen that the reasons for the migration of the participants are quite diverse. Although a few of the participants show cultural affinity as the reason, the general impression obtained from the interviews is understood that the main reason why Turkey is preferred by almost all families is cultural proximity. Some of the participant’s views on this theme are as follows:

In 2016, when my sister fell ill with leukemia, we decided to continue her treatment in Turkey. After her treatment, we moved to Turkey because the village life was not suitable for her in terms of health, and also because of the constant health checks. (S1)

…We came to Turkey for the education of my brothers and me. So we were living in Azerbaijan, my brother is at a university in Georgia and we settled there a few years later. I came to Turkey in the 10th grade. My parents brought me back to Georgia. I stayed here with my uncles and studied for a while, then my family came here, and now I am with my family. (S3)

…We immigrated to Turkey because of the war; it was the reason for us, so we were going to move eventually, but it developed suddenly because of the war. The reason we chose Turkey was that it is a Muslim country, we wanted to live under a flag, and we wanted to have a flag. (S8)

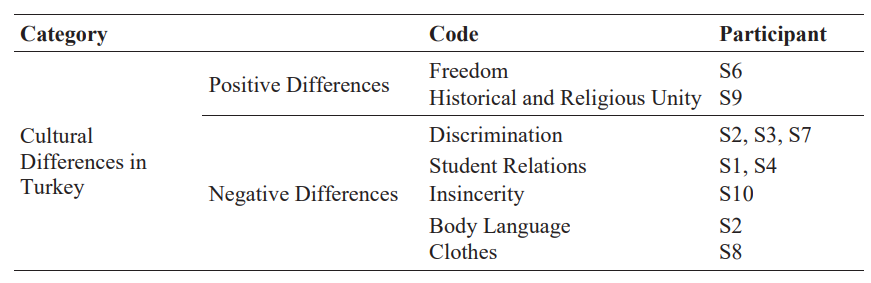

Although schools have their own cultures, all schools also reflect the basic characteristics of the national culture they are in. Immigrant students encounter the culture of their newly settled society through schools. The experiences of the participants regarding the cultural differences they encountered are shown in Table 2.

Since most of the time spent in schools is actually spent in classrooms, the similarity of classroom practices plays an important role in the adaptation of immigrants to schools

Table 2. Cultural Differences in Turkey by Place of Migration

Cultural differences or similarities significantly affect immigrant students’ school adjustment and success. It is seen that Meskhetian Turkic students list more cultural differences that can be considered negative. The exemplary participant comments are as follows:

People around me get along with each other in different signs. At first, I couldn’t understand them. (S2)

What caught my attention was that when we came to Turkey, people were not very friendly; they were asking questions like why you came and when will you leave, but I did not encounter such problems in Ukraine. (S3)

…In the daily life here, especially the girls dress in a way that I have never seen before in Georgia or Ukraine. Different and expensive clothes and shoes. (S8)

…People were more warm and sincere to each other in the village life. I saw that people in Turkey are cold and distant. (S10)

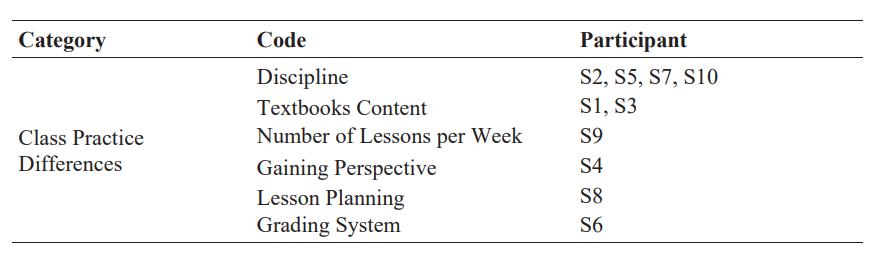

Since most of the time spent in schools is actually spent in classrooms, the similarity of classroom practices plays an important role in the adaptation of immigrants to schools. The participants’ experiences regarding the course and in-class practice differences are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Course and Class Practice Differences

As seen in Table 3, compared to the education they received before, the main point about the difference of the Turkish education system is lack of discipline. Some participant views on the theme are as follows:

…I think there is a huge difference in subject between the courses we take in our country and the courses here. The fact that the subject content of the textbooks in Turkey is difficult and detailed (History, Literature-Turkish), and I think these extra details make us tired while reading. (S1)

The point is, schools in Russia are multi-disciplinary, there are a lot of activities in Russia, and it has improved us a lot. For example, we have a graduation in 4th grade, and it happens at 9, it happens at 11, we make photo albums for every graduation, there were a lot of competitions at school. (S2)

…Russian literature and history lessons were different, we were going through the history of all countries, and we had a different point of view. In-class practice, there was an awareness of grades. We used to get a grade even when we were on the blackboard, and this grade would have been important, but here only the exam grade is evaluated. In Russia, it was based on rote, and we used to memorize poems for long pages, but there is no such system in Turkey. (S4)

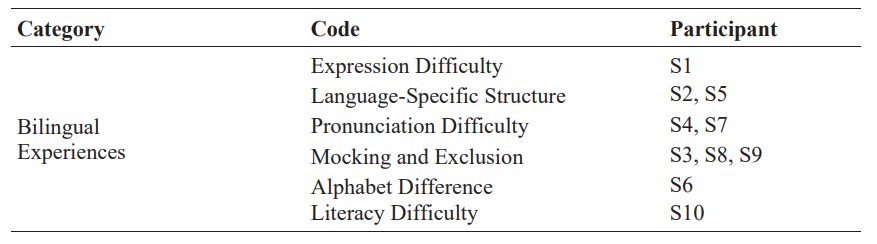

Language skills are key to the adaptation and integration of immigrants. The primary policy to ensure the integration of immigrants all over the world is to effectively teach the language of the host society. The adaptation problems experienced by the participants due to bilingualism are given in Table 4.

Table 4. The Adaptation Problems in School or Social Environment Due to Bilingualism

As it is well known, the source of many problems that immigrants experience in education is their inadequacy in language skills. The situation seems to be the same for the Meskhetian Turks. Some participant views on the theme are as follows:

When I first came to Turkey, I had a hard time expressing myself. Since I am a shy person as a personality, I was having difficulties socializing with those around me. In my opinion, the increase of guidance lessons about how we treat people at school was not prejudiced about people coming from abroad like me, the importance of empathy needs to be reinforced. (S1)

Words and sentences used metaphorically. The name of a product is in Turkish in expressing ourselves. For example, there were times when I even typed letters without knowing what a comma was. Or, I did it by looking at the verb-like translation. It was difficult for me to explain the meaning of the sentence, the meaning of the word, or to change a sentence with a word. (S2)

Of course, I didn’t have a very good Turkish in Turkey. My friends were even making fun of what I said wrong, there were a lot of words I didn’t know, and I couldn’t express myself. (S3)

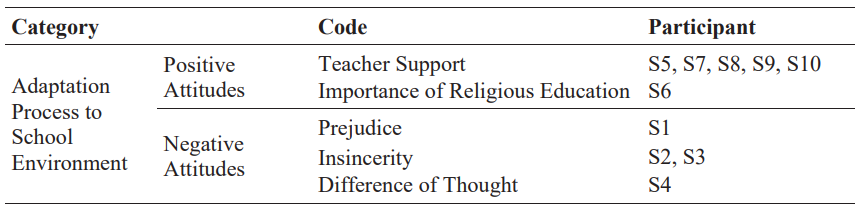

Schools, which are a small sample of societies, are also an important indicator of societies’ attitudes towards immigrants. Schools are also very conducive environments to analyze the attitudes of societies towards immigrants and to start improving policies. The participants’ experiences during their adaptation to the school environment are given in Table 5.

Schools are also very conducive environments to analyze the attitudes of societies towards immigrants and to start improving policies

Table 5. Experiences in the Adaptation Process to the School Environment

In this table, it is seen that positive attitudes such as teachers’ support and prejudices take place together. This phenomenon may represent the ambivalent attitudes towards immigrants in the bigger society. Some participant views on the theme are as follows:

I realized that my classmates were prejudiced against me because I had just arrived in the first semester. This had a bad effect on my psychology of getting used to the environment. As time went on, I started to make friends and get used to the environment, albeit slowly, because I had to get used to it. As for my teachers, they always supported me. Perhaps it would have been more difficult for me to keep up with the environment without them. My class teacher and guidance counselor often had personal conversations with me. They helped me a lot in this process. (S1)

Friends in Turkey are not very friendly. I always took the first step, now I have very nice friends, but of course, they behaved with prejudice at first. The teachers were mostly close, and they were told when we did not understand, some of the teachers were asking me questions about Georgian-Azerbaijan education and religion. (S3)

I haven’t had significant problems personally, but there may be people who do because we come to an unfamiliar environment, it is a little difficult for us to adapt, there is more difference of opinion, we look from a different window, so there can be a difference of opinion. For example, I am studying tourism, and since my Russian is good, people like me can do internships at hotel receptions. (S4)

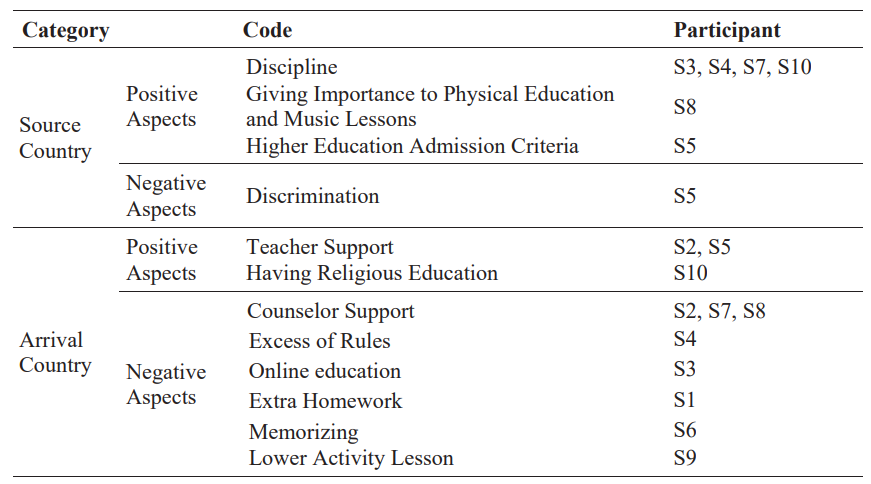

People tend to evaluate the educational services they receive in terms of their quality and develop positive opinions about institutions that offer quality products/services. For this reason, one of the most important issues in politics is developing positive images and perceptions. At the last stage of the interviews, the participants were asked about their general perceptions of education in their country of origin and Turkey. The participants’ views in this context are given in Table 6.

Table 6. Comparison of the Country of Migration and the Country of Arrival in Terms of Education

The participants’ views presented in this table regarding education they get in the country they migrated to and the country of destination are compared in terms of positive and negative aspects. It is seen that some of the participating students attribute a positive meaning to the education in the field of high discipline, art, and sports in the Russian/Eastern bloc education culture and feel the lack of these, while others emphasize the value of warm teacher attitudes and the existence of religious education. Some participant views on the theme are as follows:

…I think that the education I have received and the education we have received in the country has put a lot of pressure on the students. I have observed that even my cousins who go to primary school are given a lot of homework. I think that an 8-year-old child is burdened with many times more homework and responsibilities. (S1)

It was more difficult in normal education, but we do not understand anything from online education, but if we had a normal education, it would have progressed well, the teachers now know me, I have friends, and it was good, but now I said that we cannot benefit from online courses properly. (S3)

The education I am currently receiving is good, yes, but I think it is incomplete, and I am in favor of a change in the system. In this respect, my personal opinion is that I prefer an education without exams. We memorize all of them. The lessons and rules are too many, and we take exams accordingly; I don’t think we get a result; we remember, we do not learn anything. We do it for the exam, but we don’t do it. Instead of not adding anything to ourselves, I would learn valuable things and take lessons. Because I can’t memorize well, I can’t do the job I want, and I’ll be unhappy no matter what job it is. (S4)

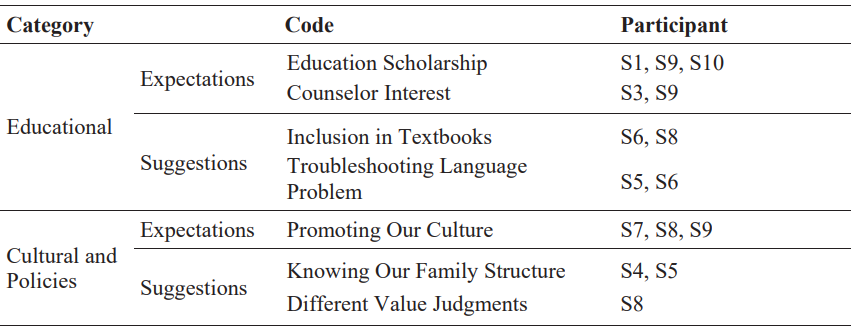

As done in most of the qualitative studies, Meskhetian Turkic immigrant students were asked about their suggestions and expectations for Turkish educational policies. Thus, the problems waiting to be solved and the prospects for the national educational policies toward immigrants are intended to be embodied. The participants’ views are given in Table 7.

It is students who have the most difficulties with the immigration phenomenon because they are separated from the friends and teachers they have known

Table 7. Expectations of and Suggestions for Turkey in the Context of Educational/Cultural Policies

The expectations of the Meskhetian Turkic immigrant students from the Turkish national educational authorities are to be provided with economic support such as scholarships and to be represented in the textbooks. On the other hand, their basic socio-cultural expectations from the school community and indirectly from Turkish society are to better promote their own cultures and make them visible. In this way, they may think that they will have a more respected position in the country they live in. Some participant views on the theme are as follows:

They can be more helpful in the lessons. For example, some did not attend online classes. Can provide financial support. Test or question banks get expensive. I don’t upload it either, and a book costs 100 TL. Our psychological condition is this. There are many people whose financial situation is not good. I’m also included. I think they can always give us more financial support regarding scholarships. (S1)

If a person is to improve himself, I think he needs to learn a new language. If our name is mentioned a lot in the books we read, it can be successful. (S6)

We have a common culture. We are together because our ancestors were one, our customs were one. (S8)

Discussion and Results

The phenomenon of migration has various social, economic, cultural, and political consequences before, during, and after the relocation itself.8 Migration has basic consequences for education, such as problems related to adaptation, class division and language, the inclusion of graduates in the workforce, different priorities of students’ parents, and the inability to adapt to urban culture.9

It is students who have the most difficulties with the immigration phenomenon because they are separated from the friends and teachers they have known; this situation can cause a psychological breakdown. Many students experience adjustment problems in education due to inequalities in the education system, language differences, and the different courses they are required to take.10

Among the reasons for the migration of Meskhetian Turkic students, cultural proximity is the prominent factor; common origin, historical ties, and kinship bonds enabled many Meskhetian Turks to migrate freely to Turkey.11 Orhan and Coşkun report similar findings in their interviews with participants who had experienced migration and echo the reasons for migration detailed in the present research.12 Accordingly, these elements should be taken into account in defining the educational and cultural needs of Meskhetian students.

Among the reasons for the migration of Meskhetian Turkic students, cultural proximity is the prominent factor; common origin, historical ties, and kinship bonds enabled many Meskhetian Turks to migrate freely to Turkey

The present research found that the participants were exposed to discrimination in both their countries of origin and destination. This finding is similar to that made by Poyraz and Güler, who reported that Meskhetian Turks were exposed to discrimination even before they immigrated to the U.S.13 This result is consistent with the findings of Keskin and Gürsoy.14 According to this research, Meskhetian Turks before and after leaving Soviet Russia were exposed to discrimination in many areas. These results support the present research’s findings of negative cultural differences encountered by immigrant students in Turkey.

Immigrant students sometimes perceive themselves as excluded because they are bilingual. Eren states that immigrant students have difficulties expressing themselves because their language skills are not sufficient.15 Due to this difficulty, they are ridiculed and ostracized by their classmates. Velázquez concludes that immigrant students become alienated from the educational system as a result of being excluded in the school environment.16 Tösten, Toprak, and Kaya emphasize that local students engage in peer bullying by mocking and excluding immigrant students.17 These results support the findings of the present study in regard to the category of experiences participants reported due to bilingualism, and indicate that problems based on discrimination persist between immigrant students and students receiving education locally. Topsakal, Merey, and Keçe state that immigrant students experience similar problems with their classmates due to language and cultural differences.18

When differences in courses and in-class practices are examined, discipline comes to the fore. Bahar and Yılmaz conclude that school rules and the understanding of discipline are strict in Turkey, and argue that school rules should be stretched so that immigrant students can adapt.19 Participants in the present study reported that schools in their countries of origin operated with a more disciplinary approach than Turkish ones. Therefore, the present findings differ from the results obtained from Bahar and Yılmaz’s studies.20 It is possible that differences in the unique school climates of the participants may account for this difference before and after migration.21

When the participants’ positive experiences during their adaptation to the school environment are examined, the support of the teachers emerges as a crucial element. While the findings of this study are in line with the results of the survey conducted by Çöplü,22 studies conducted by Börü,23 Ersoy, and Turan conclude that teachers exhibited a discriminatory attitude toward and excluded immigrant students.24 The difference in the results may be due to the fact that teachers and students do not attend sufficient in-service courses and that teachers across the country have not received sufficient, consistent training in handling cultural differences in the classroom environment. In the studies carried out in this field, factors that affect the results include ethnicity, the socio-economic level of the school, and the settled culture of the city. In particular, the indigenous students’ parent profile plays an important role in determining the school staff’s perspective on migrant students.

The migrants’ need for psychosocial support and the facilitation of social integration appears to be reflected in their sense of the inadequacy of the counseling services available to them

When the positive and negative aspects of the country of immigration and the country of destination are compared in terms of education, the positive and negative aspects of the discipline and discrimination of the source country come to the fore. Ersoy and Turan support the findings of this research, concluding that guidance services for immigrant students are insufficient and that in some cases the students are not even aware of the existence of guidance services.25 Teachers’ positive attitudes toward immigrant students, together with guidance services, can help ensure that immigrant students are more successful and that they are not discriminated against in their new country.26

The participants in the present study stressed the need for educational scholarships; Topsakal et al. reach similar conclusions and argue that immigrant students should be supported financially.27 Financial support to immigrant students significantly improves their integration with the host society and their chances of success.28 Among the cultural expectations of the participant students in the present study, the desire for the promotion of their own culture stands out. Piliouras and Evangelou report similar findings, stating that if immigrant students are not allowed to promote their cultural characteristics, it may affect their academic success and the healthy development of their own identities.29 Cummins emphasizes that “rejecting the language and culture of the student is rejecting the student himself” and when the message, “leave your language and culture to the students at the school door” is given, “students leave an essential part of their identity at the school door,” leading to a feeling of rejection in the classroom.30 Cummins argues that such practices may cause them to be unsuccessful in both internal learning and academic development.

In today’s world, migration between countries is common and at times intense. Countries’ economic, health and education systems are affected by migration, and politicians are deeply divided regarding immigrants. The statements they make to get votes from the local people can lead to social division and foster anti-immigration attitudes, in some cases eliminating the opportunity to provide quality education for migrants. While governments are faced with this situation, immigrants face different attitudes in the places they go. Meskhetian Turks, who came to Turkey with a sense of cultural affinity, have had both positive and negative experiences depending on the attitudes they encountered. From a long-term perspective, making efforts to ensure positive experiences for these historically interconnected communities will improve economic, social, and political cooperation; and foster positive relationships between immigrant and indigenous citizens. Therefore, it may be helpful to consider immigrant education policies carefully from this perspective.

Policy Recommendations

The educational experiences of Meskhetian Turkic immigrants in Turkish schools will affect their attitudes towards Turkey. Therefore, educational experiences will play an important role in the future of relations between these two historically interconnected communities. It will be beneficial for education decision-makers to systematically analyze the needs of these segments of the population and produce solutions to their problems both at the national and local levels. It was found that the support of the guidance service is perceived as inadequate by the research participants. The migrants’ need for psychosocial support and the facilitation of social integration appears to be reflected in their sense of the inadequacy of the counseling services available to them. Policymakers should keep in mind that social integration can only be achieved through the participation of all stakeholders in the school ecosystem, including parents from the host community. One major finding from this study is that immigrant students want to introduce and share their own culture with their host community. Including the cultures of immigrant students in the school’s event calendar may assist them in effectively integrating with the school and therefore with the society in which they live, thereby increasing their sense of belonging. Participant students stressed their need for educational scholarships; to increase their chances of academic success, additional financial resources are recommended.

Table 8. Demographic Characteristics of Participants

Endnotes

1. Marmara University, Institute of Educational Sciences, Research, and Publication Ethics Committee decided that this research was ethically appropriate with the decision numbered 2021/2/74, Protocol Number 2021/230 on February 26, 2021, and notified the approval of the ethics committee with document number 2100082153.

2. “Göç Terimleri Sözlüğü (Translated by B. Çiçekli),” IOM, (2009), p. 22; Gordon Marshall, Sosyoloji Sözlüğü, (Ankara: Bilim ve Sanat Publications, 1999), p. 685.

3. Taylan Akkayan, Göç ve Değişme, (İstanbul: İstanbul University Faculty of Literature Publications, 1979); Türken Çağlar, “Göç Çalışmaları İçin Kavramsal Bir Çerçeve,” Toros University İİSBF Journal of Social Sciences, Vol. 5, No. 8 (2018), retrieved from https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/iisbf/413560, pp. 26-49; Serkan Çalişkan, “Adrıan Paci’nin Eserlerinde Göç ve Kimlik Olgusu,” Kilis 7 Aralık University Journal of Social Sciences, Vol. 9, No. 17 (2019), pp. 13-21; Süleyman Ekici and Gökhan Tuncel, “Göç ve İnsan. Birey ve Toplum,” Journal of Social Sciences, Vol. 5, No.1 (2016), pp. 9-22; İnan Özer, Kentleşme, Kentlileşme ve Kentsel Değişme, (Bursa: Ekin Kitapevi Yayınları, 2011), p. 33; Mete Kaynar and Gökhan Ak, “19 Yüzyılda Çokkültürlü İmparatorluktan Ulus-Devlete Geçişte Sürgün ve Göç: Malakanlar Örneği,” Journal of Academic Reviews, Vol. 10, No. 2 (2015), pp. 1-22; Mehmet Ali Kirman, “Sosyal Bir Olgu Olarak Göç,” in Ali Akdoğan, Süleyman Turan, Erol Sungur, Emine Battal, M. Enes Vural (eds.), İslam Coğrafyasında Terör, Göç ve Mültecilik, (Ankara: Recep Tayyip Erdoğan University Publications 2017); Samet Küçüktürk, “Canik ve Göç 1800-1923,” Journal of Black Sea Studies, Vol. 14, No. 27 (2019), pp. 293-298; Fjolla Lecaj, “Küreselleşme Göç ve Kadın,” International Humanities and Social Sciences Review Journal, 3, No. 1 (2019), retrieved from https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/ihssr/548830, pp. 49-58; Mehmet Şentürk, Fatih Tıkman, and Esat Yıldırım, “Metaforuna Yolculuk: Bir Fenomenolojik Çalışma,” Kilis 7 Aralık University Journal of Social Sciences, Vol. 7, No. 14 (2017), pp. 104-126; William Petersen, “A General Typology of Migration,” American Sociological Review, Vol. 23, No. 3 (1958), pp. 256-266.

4. İbrahim Hasanoğlu, “Ahıska Türkleri: Bitmeyen Bir Göç Hikâyesi,” Journal of Turkish World Studies, Vol. 16, No. 1 (2016), retrieved from https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/egetdid/380838, pp. 1-20.

5. Kahraman and İbrahimov, “Kafkaslar’dan Sürgün Bir Toplumun Bitmeyen Göçü.”

6. Elif Tekin İftar, Dilek Erbaş, and Gönül Kır, İşlevsel Değerlendirme: Davranış Sorunlarıyla Başa Çıkma ve Uygun Davranışlar Kazandırma Süreci, (İstanbul: Kök Yayıncılık, 2005).

7. Rukiye Şimşek, Toplumsal Uyum ve Din: Erzincan Üzümlü’de Yaşayan Ahıskalılar Örneği, (Unpublished Master Thesis), Necmettin Erbakan University, (2020).

8. Mehmet Fikret Gezgin, “İşgücü ve Avustralya’daki Türk İşçiler,” İstanbul University Faculty of Economics Publications, Vol. 546, No. 16 (1994).

9. Yüksel Kaştan, “Türkiye’de Göç Yaşamış Çocukların Eğitim Sürecinde Karşılaşılan Problemler,” International Journal of Social and Educational Sciences, Vol. 2, No. 4 (2015), retrieved from https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/ijoses/614109.

10. İftar et al., İşlevsel Değerlendirme.

11. Eray Aktepe, Mustafa Tekdere, and Abdullah Şuhan Gürbüz, “Toplumsal Uyum ve Bütünleşme Bağlamında Erzincan’a Yerleştirilen Ahıska Türkleri Üzerine Bir Değerlendirme,” Journal of Migration Studies, Vol. 3, No. 2 (2017), retrieved from https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/gad/571053, pp. 138-169.

12. Orhan and Coşkun, “Zorunlu Göçlere Yeni Bir Örnek.”

13. Tuğça Poyraz and Abdurrahim Güler, “Ahıska Kimliğinin Göç Sürecinde İnşası: Amerika’ya Göç Eden Ahıska Türkleri,” Bilig, Vol. 91 (2019), pp. 187-216.

14. Serhat Keskin and Hazar Ege Gürsoy, “Sovyet ve Sovyet Sonrası Dönemde Ahıska Türklerinin Karşılaştıkları İnsan Hakları İhlalleri ve Ayrımcılıklar,” Uluslararası Suçlar ve Tarih, Vol. 18 (2017), pp. 13-46.

15. Zeynep Uğurlu Eren, “Suriyeli Sığınmacı Öğrencilerin Okula Uyum Sorunlarının Çözülmesi ve Desteklenmesinde Öğretmen Etkisi,” in Adem Solak and Vahap Özpolat (eds.), Zorunlu Göçler ve Doğurduğu Sosyal Travmalar, 185-248.

16. Loida C. Velázquez, “Voices from the Fields: Community-Based Migrant Education,” New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, No. 70 (1996), pp. 27-35.

17. Rasim Tösten, Mustafa Toprak, and M. Selman Kayan, “An Investigation of Forcibly Migrated Syrian Refugee Students at Turkish Public Schools,” Universal Journal of Educational Research, Vol. 5, No. 7 (2017), pp. 1149-1160.

18. Cem Topsakal, Zihni Merey, and Murat Keçe, “Göçle Gelen Ailelerin Çocuklarının Eğitim Öğretim Hakkı ve Sorunları Üzerine Nitel Bir Çalışma,” Journal of International Social Research, Vol. 6, No. 27 (2013).

19. Hüseyin Hüsnü Bahar and OğuzhanYılmaz, “Ahıska, Göç ve Eğitim,” Journal of Qualitative Research in Education, Vol. 6, No. 2 (2018), pp. 238-257.

20. Bahar and Yılmaz, “Ahıska, Göç ve Eğitim.”

21. Fatih Pehlivan and Hasan Demirtaş, “Ortaokul ve Liselerde Yaşanan Disiplin Problemlerinin Çözümüne Yönelik Yönetsel Uygulamalar,” International e-Journal of Educational Research, Vol. 10, No. 2 (2019), retrieved from https://doi.org/10.19160/ijer.584206, pp. 31-50.

22. Fırat Çöplü, “Göçmen Öğrenciler için Okul Uyum Programı Geliştirmeye Yönelik bir Taslak Çalışması,” Unpublished Master’s Thesis, Ahi Evran University, (2019).

23. Neşe Börü and Adnan Boyaci, “Öğrencilerin Eğitim-Öğretim Ortamlarında Karşılaştıkları Sorunlar: Eskişe,” Turkish Studies, No. 11 (2016), retrieved from https://doi.org/10.7827/TurkishStudies.9818, pp. 122-123.

24. Ali Fuat Ersoy and Nilay Turan, “Sığınmacı ve Göçmen Öğrencilerde Sosyal Dışlanma ve Çeteleşme,” Third Sector Social Economic Review, Vol. 54, No. 2 (2019), retrieved from doi:10.15659/3.sektor-sosyal-ekonomi.19.05.1103, pp. 828-840.

25. Ersoy and Turan, “Sığınmacı ve Göçmen Öğrencilerde Sosyal Dışlanma ve Çeteleşme.”

26. Stuart A. Karabenick and Phyllis A. Clemens Noda, “Professional Development Implications of

Teachers’ Beliefs and Attitudes Toward English Language Learners,” The Journal of the National Association for Bilingual Education, 28, No. 1 (2004), retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/15235882.2004.10162612.

27. Topsakal et al., “Göçle Gelen Ailelerin Çocuklarının Eğitim Öğretim Hakkı ve Sorunları Üzerine Nitel Bir Çalışma.”

28. Marco Albertini, Giancarlo Gasperoni, and Debora Mantovani, “Whom to Help and Why? Family Norms on Financial Support for Adult Children among Immigrants,” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, Vol. 45, No. 10 (2019), pp. 1769-1789.

29. Panagiotis Piliouras and Odysseas Evangelou, “Teachers’ Inclusive Strategies to Accommodate 5th Grade Pupils’ Crossing of Cultural Borders in Two Greek Multicultural Science Classrooms,” Research in Science Education, Vol. 42, No. 2 (2012), retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-010-9198-x, pp. 329-351.

30. Jim Cummins, “Bilingual Children’s Mother Tongue: Why Is It Important for Education?” Sprogforum, Vol. 7, No. 19 (2001), retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/2kvpn7fe, pp. 15-20.