Introduction1

International security theories generally identify economic power as a key determinant of military power, and thereby of security, but there is usually not much explanation about the determinants of economic power.2 In this paper, a simple yet comprehensive model of economic power is introduced and integrated with an international security model. The economic power model is unique to this article although it was influenced by well-known theories of economic growth that emphasize the role of exports and technical progress. The international security model is a Realist-type model based on the assumption of states functioning in an anarchic world order. The integrated security model explains how the determinants of economic power affect international security. The integrated model yields policy implications for security and suggests policies for enhancing the international security of a regional or of a major power.

International security theories are in general conceived and articulated for explaining and predicting the behavior of major powers.3 However, there are key states, with significant economic and military power in important regions of the world, whose behavior have a significant impact on the political fortune of these regions if not on the world. This article provides a discussion of the determinants of economic power and international security applicable to both major and regional powers.4

A major power, completely self-sufficient in producing the most advanced weapons, may have so much economic and military power that it can readily deploy a substantial and a decisive force in any part of the globe to achieve its security objectives. Such a state, a superpower, can be considered a de facto member of all regions in the world

The objective of this paper is to present a straightforward theoretical framework, a model, which can be used to explain and predict the impact of developments in economic power on the security of a major or regional power.5 In the following section, characteristics of major and regional powers are discussed. In the next section a detailed discussion of the determinants of economic power is presented. This is followed with an identification of the international political system in which states function. The international system is presumed to be anarchic and, accordingly, regional and major powers concerned about their security are motivated to maximize their military power. The determinants of military power are discussed next. The following section contains policy implications of this approach to international security. The final section includes concluding remarks.

Major and Regional Powers

Major powers possess substantial economic and military power and are capable of employing military power and inflicting substantial damage on another major power or a group of other states in their region. Major powers are self-sufficient in producing most of their weapons and have a capability of projecting appreciable military force in areas beyond their regions.6 Regional powers possess significant economic and military power and are capable of employing military power and inflicting limited damage to other states in their region. Moreover, they are able to produce some of their weapons, however, cannot project significant military force in areas beyond their regions.

Identification of major and regional powers consistent with the above descriptions is not straightforward in concrete terms. However, such a concrete classification is useful for identifying key states involved in a regional security competition or a conflict and provides an empirical example of the regional and major power definitions introduced. While recognizing the limitations, the following concrete classifications can be made for various countries.7

In Europe, the UK, Germany, France, and Russia are major powers, while Spain, Italy and Poland are regional powers. In Eastern Asia, in addition to major powers Russia, Japan and China, there are two regional powers, North and South Korea, while India and Pakistan are the regional powers in Southern Asia. The regional powers in the Middle East are Turkey, Iran, Israel, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia. In Eastern Europe, the regional powers are Poland and Ukraine, with the two major powers being Germany and Russia. In the western hemisphere there is one major power, the U.S., with regional powers: Canada, Brazil, and Argentina.

A region can be considered to be a geographical entity or a political set of states. A state can be in more than one region; Turkey is in the Middle East but it is also part of the Black Sea region with other states like Ukraine and Russia. At times a state may be able to project effective force into a region although it is not a member of that region. The Russian military intervention in the Syrian Civil War is an example. In such cases that state can be considered as a de facto member of the region.

A major power, completely self-sufficient in producing the most advanced weapons, may have so much economic and military power that it can readily deploy a substantial and a decisive force in any part of the globe to achieve its security objectives. Such a state, a superpower, can be considered a de facto member of all regions in the world. The only state that has such a global reach is the U.S. Accordingly the U.S. should be considered a member of any region, such as, Eastern Europe or the Middle East or East Asia.

A Model of Economic Power

Economic Theories of Growth

There are no well-known theories of economic power in the conventional economics literature. However, there are renowned theories of economic growth that have implications for constructing a theory, a model of economic power. There are two basic approaches to economic growth: export-led growth models and neoclassical growth theories. In export-led growth models, the main driver of the economy is exports, while in neoclassical theory technical progress is the key determinant of growth.8

In a fully developed export-led growth model such as the Kaldor version, exports are determined by world demand and the price of exports relative to the domestic price level. The domestic price level is in turn set by wages relative to productivity. This type of a model suggests that a rise in productivity would result in a rise in exports, assuming that wages remain the same.9

In the Kaldor export-led growth model productivity is postulated to be a positive function of aggregate output. Higher output, through its effect on the scale of production, lowers costs and increases productivity. This feature of the model, by making productivity a function of output, makes the export-led model a virtuous circle where a rise in exports leads to a rise in productivity and a further rise in exports and output. This model, describing a virtuous circle, suggests that once set in motion the economic growth would continue.

The neoclassical growth theory has three determinants: labor, capital, and technical progress. Labor and capital are the basic factors of production. Land is not included as a factor of production since land is no longer an important determinant of economic growth as it was before the 1800s. In this model, a rise in factors of production and of technical progress results in a higher aggregate output and economic growth.10

Economic power can be defined as the inclusion of all varieties of the means of production (capital stock), size of the labor force, education and health of labor, management and organizational skills, technical capability, financial wealth, and non-reproducible natural resources like oil reserves of a state

In the neoclassical model diminishing returns to aggregate output is assumed with respect to a rise in factors of production, labor and capital. However, technical progress allows for accelerating expansion in output by raising the productivity of the economy. Identification and emphasis on technical progress make the neoclassical model consistent with the rapid expansion of growth and productivity observed starting in the 1800s.

Economic Power and Its Determinants

Economic power is a frequently used but rarely defined and problematic term to measure. It has no place in conventional economic theory but is used frequently in political science. It has to be a stock rather than a flow variable, although in practice it gets measured by GDP, a flow variable. Measuring a stock variable with a flow variable can lead to misleading and erroneous results. A comprehensive economics concept, wealth, a stock variable, is a more suitable proxy variable for economic power, but it is not readily available and difficult to measure. The following definition introduced is a definition emphasizing the stock aspect by identifying the elements of economic power at a certain time. There is no empirical measure readily available that is consistent with this definition, but a rough measure can be made by considering a set of empirical variables that map with the elements of the definition below.

Economic power can be defined as the inclusion of all varieties of the means of production (capital stock), size of the labor force, education and health of labor, management and organizational skills, technical capability, financial wealth, and non-reproducible natural resources like oil reserves of a state.11 Financial wealth is primarily international foreign exchange assets including reserve assets.

Fundamental determinants, factors that have a long-lasting effect on the economic power of a regional or major power over time, are investments, exports, population, technical progress, and the health and education of the population. Investments are additions to the stock of capital. Exports include both goods and services. Services include such items as medical services and tourism. Technical progress includes all innovations that improve productivity. Health and education of the population likewise affect the productivity of a nation. These determinants are also valid for the determination of the economic power of enemies of a state.

The geographic location of a state and its approximate access to large markets and oceans that provide relatively cheaper transportation of its goods are natural determinants of its economic power

Trade with its enemies could improve the economic power of a regional or major power, but trade is also likely to be beneficial to its enemies. Trade with potential enemies is risky and if not necessary should be avoided as trade may improve the economic power of its enemies more than that of the state and thereby result in a decline in its relative economic and military power and thereby in its security. It may be possible that the extensive trade and financial interaction between China and the U.S. in recent years has been more beneficial to China.

The U.S. benefited from relatively lower interest rates due to the Chinese purchase of U.S. Government Securities, and U.S. consumers benefited from low-priced Chinese made goods. But, China benefited from ready access to large U.S. consumer markets that let its exports expand rapidly. More importantly, China benefited from the know-how and advanced technology of U.S. firms producing and operating in China.

Investment

Investment adds to the capital stock of a nation. Capital stock consists of machinery, roads, airports, harbors, factories, buildings, hospitals and other medical facilities, energy-production facilities and other means of production that raise the productivity of a nation. The fundamental source of investment of a state is the savings from aggregate output after satisfying the consumption of goods and services. A rise in output of a nation allows for an increase in savings and investment, and economic power.

Investments are based on future profitability expectations of entrepreneurs. These expectations are sensitive with respect to the political stability in a state. Political instability hampers investment by adversely affecting expectations about the future. Political instability also has an adverse effect on tourism. In some states, tourism revenues are an important source of foreign exchange required for the financing of imported consumption and investment goods. Also, in some states, government expenditures are a significant component adding to the capital stock. Amounts and types of these investments are determined by respective governments.

Exports

Exports increase the economic power of regional and major powers. Exports expand the potential markets of a nation. Exports by raising the extent of the market lead to a further division of labor and specialization, increase productivity and expand production. Larger production leads to a further rise in productivity and lower production costs and results in greater exports and output. Competition in overseas markets induces firms to raise productivity and lower the cost of production.

Exports furthermore increase investment spending by creating additional demand for the output of domestic companies. Usually, exports are the primary source of foreign exchange required for the financing of imported consumption and investment goods and scarce military goods like advanced stealth aircraft. Most states, economically and technically, are not capable of producing state of the art advanced weapon systems. The purchase of fifth generation fighter aircraft (F-35) from the U.S. by various states like Israel, Turkey and the UK is an example.

Technical Progress

Technical progress increases the economic power of a nation by raising the productivity of its labor force. Advanced robots, digital tools, and other high tech means of production are examples of technical progress in production. A rise in investments and exports induce technical progress either by being included in new equipment or in the know-how required by a rise in investments and exports. Higher productivity allows goods to be produced cheaper than in other nations and boosts exports and thereby economic power.

Population

The size of the population affects economic power. Population is the primary source of a state’s labor force and population is a basic factor of production. In some states, like the U.S. and Germany, migration is an important source of the labor force. Population is also the main determinant of consumption. A rise in population increases the demand for goods and services and production and ultimately raises the capital stock of a nation. Modern production requires a well-educated and healthy population. The health and education of the population are important determinants of a nation’s productivity and economic power.

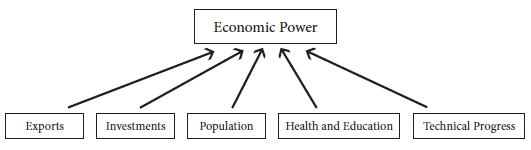

Figure 1, presents the key elements of the model of economic power. In this simple flow-chart representation, determinants of economic power are assumed to have a unidirectional causality, from determinants to economic power.12

Figure 1: Model of Economic Power

Natural Determinants

The natural determinants of economic power can be important for some states. The geographic location of a state and its approximate access to large markets and oceans that provide relatively cheaper transportation of its goods are natural determinants of its economic power. For instance, Mexican exports benefit from its convenient and close access to large U.S. markets.

If a state cannot protect its citizens and maintain sovereignty against its enemies, that state cannot survive in the anarchic world order; and the collapsed state will be unable to fulfill any of its other objectives

Non-reproducible resources, like oil, are a natural determinant of the economic power of a state. Saudi Arabia has economic power due to its large reserves of crude oil. The geographical location of a state with respect to nearby areas where there are natural resources like oil affect the economic power of a state. For example, Turkey benefits from being a natural bridge between oil and gas rich areas in the Middle East, Russia and Azerbaijan and the consuming nations in Europe.

A Model of International Security

Anarchic World Order and Security

International security is about maintaining the sovereignty and safety of a nation. Safety and sovereignty of a state are always threatened in the anarchic world order; there is no effective world government that could insure the safety and sovereignty of a state.13 In the anarchic international order, regional and major powers are compelled to maximize their military power. As long as the international order remains anarchic, the security competition among these states will endure and at times lead to war. In order to achieve global security and peace for all the states in the world, the anarchic system has to be replaced with a global security system that would induce regional and major powers to abandon maximizing their military power and to outsource their security to the global security system.

But the recent history of the world indicates that such a peace-creating global international security system has not been possible. The United Nations, established after the Second World War, remains a weak, ineffectual institution far from making member states accept international law and order enforced by an all-powerful and supreme organization. A revelation of the lack of an effective and powerful institution is the Israeli government’s behavior of ignoring the United Nations recommendation that Israel should not establish new settlements in the West Bank or East Jerusalem.14

U.S. President Trump and Chinese President Jinping attend a business meeting at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on November 9, 2017. FRED DUFOUR / AFP / Getty Images

U.S. President Trump and Chinese President Jinping attend a business meeting at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on November 9, 2017. FRED DUFOUR / AFP / Getty Images

Although anarchic world order is here assumed to be the realistic description of the international system, there are alternative views of the international order and these views lead to different conclusions about the behavior of major and regional powers. A well-known alternative approach, complex interdependence, emphasizes the interdependence of states.15 This view of world order yields predictions and conclusions much different compared to the anarchic world order assumption. In this approach, states are not the sole important actors, military power is not the only important instrument of policy, economic sanctions and incentives matter, welfare is the primary goal. These assumptions contradict those of realism, emphasizing international security, military power, and nation states.

The complex interdependence theory appears to describe an idealistic rather than the real world of international relations. It is able to explain relations among a limited number of major and regional powers. The relations between contemporary France and Germany are consistent with complex interdependence but not much else. This approach is an unrealistic and unreliable way of explaining and predicting relations in key regions of the world, such as Eastern Europe, Middle East, Western Asia. Here realism and anarchic world order is adopted, a more general approach compared to complex interdependence.

In the anarchic world order, a state will accumulate military power against potential enemies, and it would have to consider other states, especially those in its own region, as potential enemies since a state has no foolproof way of predicting the intentions of other states. In the anarchic world order, a regional or a major power can use military power, including war, to attain its security objectives.16 At times a state may have no other choice but to use military force to achieve its security objectives. Vivid recent examples are the First and Second Gulf Wars –the U.S. war against Iraq to liberate Kuwait and the invasion of Iraq by the U.S. and other forces.

Spatial location of a state is not a variable that can change like military power; it is a natural constant. A state is naturally blessed or handicapped by its geographical location

National security is not about improving the environment, economic welfare, the health of the citizens or establishing and maintaining democracy in a state or in the world.17 These are desirable objectives of a state, and there are other desirable goals, but in the hierarchy of state goals, the security of a nation is the highest goal.18 If a state cannot protect its citizens and maintain sovereignty against its enemies, that state cannot survive in the anarchic world order; and the collapsed state will be unable to fulfill any of its other objectives.

Military power is the fundamental determinant of the security of a regional or major power. It includes all means of offensive and defensive weapons, soldiers, technology, intelligence capabilities, military management, know-how and organizational skills, intelligence capabilities, and the quality and morale of its military leaders and soldiers. Military weapons include both conventional and nuclear.

Other factors such as diplomacy, alliances and soft-power can be important at times but they are not permanent and reliable determinants of security.19 Alliances were stable during the Cold War, and members of the alliance were forced to follow the leader of the alliance even if some of their important security objectives clashed with that of the leader. The alliance remained stable because of the followers’ need for protection against the leader of the opposing alliance. On occasion, states can pursue their security interest even at the expense of retribution by the leader of the alliance. During the Cold War, the military intervention in Cyprus by Turkey, and the U.S. reprisal of cutting arms supply is an example. Alliances can be an important determinant of security but they cannot be considered to be as reliable as a state’s own military power.

An expansion in the military power of current and potential enemies lowers the security of a state. Even if there is no change in the military power of a regional and major power, a rise in conventional or nuclear military power of the enemies would reduce the security of a nation. A decrease in the military power of other states improves the security of a state.

Maximizing economic power without expanding military power will not raise the security of a nation. A policy of expanding economic power while neglecting military power makes a state potentially vulnerable in the anarchic world. Japan is an example of a major power that finds itself increasingly vulnerable against extensively and nuclear armed North Korea and China. This growing imbalance recently has forced Japan to increase its military spending.

The physical location of a state is a natural determinant of its security. The U.S. is protected by oceans on the west and east and benefits from this isolated location. However, a state like Poland is open to an attack from both directions. During the Second World War, Poland was invaded by Germans from the west and by Russians from the east. Geographical location, therefore, makes Poland less secure while the U.S. more secure. The location of Canada allows it to benefit from the security provided by the U.S. military force. Spatial location of a state is not a variable that can change like military power; it is a natural constant. A state is naturally blessed or handicapped by its geographical location.

Geographical size of a state also affects the security. A large state like Russia is more secure in defending itself by being able to retreat to its hinterland. During the Second World War Russians retreated to the east and German forces advanced and become logistically weak and vulnerable. Geographically, large states like the U.S. and Russia are likely to survive a limited nuclear war but a small state like Israel may be totally destroyed and no longer exist.

The geographical terrain and weather can also affect security. The cold Russian winter contributed to the defeat of the German Army during the Second World War. A reason that Switzerland in the Second World War was able to remain neutral and was not invaded was its mountainous geography along with a small but strong military force that kept Germany out.

Maximum Military Power

A state’s ability to accumulate military power, whether it is a regional or major power, is limited by its economic power, technical capabilities, and the size and age of its population. However, a state will strive to acquire as much military power as possible. A state will be especially concerned with the military power of its immediate neighbors and of enemies in its region and will try to be militarily the most powerful in the region to insure safety and sovereignty. To achieve this goal a state may use force and go to war but since wars are costly they are employed as a means of last resort.

A good example of the need of regional and major powers to accumulate as much power as possible is their quest to acquire nuclear weapons. States recognize the great equalizer effect of nuclear weapons against their powerful enemies and, to insure their security and sovereignty, they deploy nuclear weapons.20 North Korea and Israel are examples of such states. Iran’s recent effort to acquire nuclear weapons is another example.

The ongoing competitive accumulation of superior nuclear weapons systems among nuclear powers is the result of states seeking more and more military power. The quest of states to maximize military power may lead to a military arms competition among them. But such a development does not stop states from attempting to acquire maximum military power in the anarchic world order and to try to be the most powerful military state in their region, and for the U.S. to be the most powerful in all regions of the world.

(L to R) Russian FM Lavrov, German FM Steinmeier and U.S. Secretary of State Rice speak to the media after their meeting in Germany on Iran’s nuclear program, which focused on limiting Iran’s potential to arm itself with nuclear weapons, January 22, 2008. SEAN GALLUP / Getty Images

(L to R) Russian FM Lavrov, German FM Steinmeier and U.S. Secretary of State Rice speak to the media after their meeting in Germany on Iran’s nuclear program, which focused on limiting Iran’s potential to arm itself with nuclear weapons, January 22, 2008. SEAN GALLUP / Getty Images

Under special conditions, a state may choose not to accumulate as much conventional and nuclear military power as possible. Security of a state may be provided by another state. Japan and Germany, especially during the Cold War, were protected by the U.S. and chose not to accumulate the maximum amount of military power including nuclear weapons. However, with the potential reduction in the commitment of the U.S., these states may try to accumulate as much military power as possible, including nuclear weapons.

Determinants of Military Power

Military power, a stock variable, in this article is defined as all means of offensive and defensive weapons, soldiers, technology, intelligence capabilities, military management, know-how and organizational skills, the quality and morale of its military leaders and soldiers. Military weapons include both conventional and nuclear. There are three fundamental determinants of the military power of regional and major powers. Fundamental determinants are factors that account for permanent changes over time of the military power of a nation. These factors are economic power, technical capabilities, and population.21

Despite the rise in the use of unmanned aircraft and other high-tech weapons systems that increasingly depend less and less on humans, the availability of a young population pool to serve in the military is a real concern to states with ageing populations

At times other factors like intensity of military threat, external and internal developments can affect the military power of a nation but these developments do not result in permanent changes. For example, a coup by the military may lower military power for a short time, however the effect will not be lasting. An explanation of changes in the military power of a nation over time requires understanding of how economic power, technical capabilities, and population impact military power.

Economic Power

Economic power, as it was defined above, includes all varieties of the means of production (capital stock), size of the labor force, education and health of labor, management and organizational skills, technical capability, financial wealth, and non-reproducible natural resources like oil reserves of a regional or major power. The primary constraint on military power is the economic power. Those resources allocated to military power have an opportunity cost, civilian consumption and investment expenditures like welfare spending and building civilian airports. A rise in economic power allows a nation to expand its military power in addition to increasing civilian consumption and investment spending.

Without the rise in economic power, an expansion of military power is difficult or impossible. Regional and major powers where military power steadily expands are usually those nations where there has been a steady expansion in economic power. Note that China had a rapid rise in economic power accompanied by a rapid rise in military power during the final years of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century.22 At times when there are ample unemployed resources, there may be a symbiotic relation between military power and economic power. These factors can affect each other in a positive way. A good example of a symbiotic relation is that of Germany and the U.S. during the Second World War. During the war, there was a simultaneous and symbiotic expansion in economic and military power in both states.

Technical Capability

Technical capability of a regional or major power enables it to employ and produce unmanned drones, modern tanks, stealth warships and aircraft, long-range smart artillery, modern submarines and other high-tech weapon systems. Technically advanced military hardware increasingly dominates modern battlefields. High-tech weapons systems increase the mobility, accuracy and effectiveness of military power. This trend increases the productivity and the effectiveness of soldiers and leads to the formation of smaller but more deadly professional military forces around the world. In many cases technical innovations first introduced into modern weapons were later applied to civilian use such as in the production of civilian aircraft.

There are enormous differences in the technical military capabilities of nations. The military technical gap between the U.S. and other states in the 21st century is extremely large. The U.S. is the only state that can produce and deploy a sophisticated stealth fighter like the F-35; other nations uniformly lag behind the U.S. in the production of state of the art weapons systems. The technical superiority of modern weapons increasingly renders less advanced weapons that are extensively deployed obsolete and ineffective. The technical superiority of U.S. military power in the First Gulf War was obvious. The Abrams MBT (main battle tank), for example, were readily able to destroy Iraqi.

Population

Population growth enables regional and major powers to expand their military power. Despite the rise in the use of unmanned aircraft and other high-tech weapons systems that increasingly depend less and less on humans, the availability of a young population pool to serve in the military is a real concern to states with ageing populations. State-of-the-art military equipment and weapons require young and educated soldiers. Stationary and declining population has been a concern for states like Germany and Russia. A large population allows a state to deploy a large military force and expand the force when required.

Unlike these states, the third-most-populous state, the U.S., with its growing population does not face the constraint of population scarcity. A state like Israel with a relatively small population is disadvantaged and needs to use its force sparingly and compensate by raising the productivity of its existing force by maintaining high firepower and a mobile force. Recent military conflicts, however, suggest that the size of a state’s population is decreasing in importance as a determinant of military power. Modern wars are getting shorter in duration and fought intensely with existing forces. There is a tendency for wars to be decided in a short time. Good examples are the First and the Second Gulf Wars.

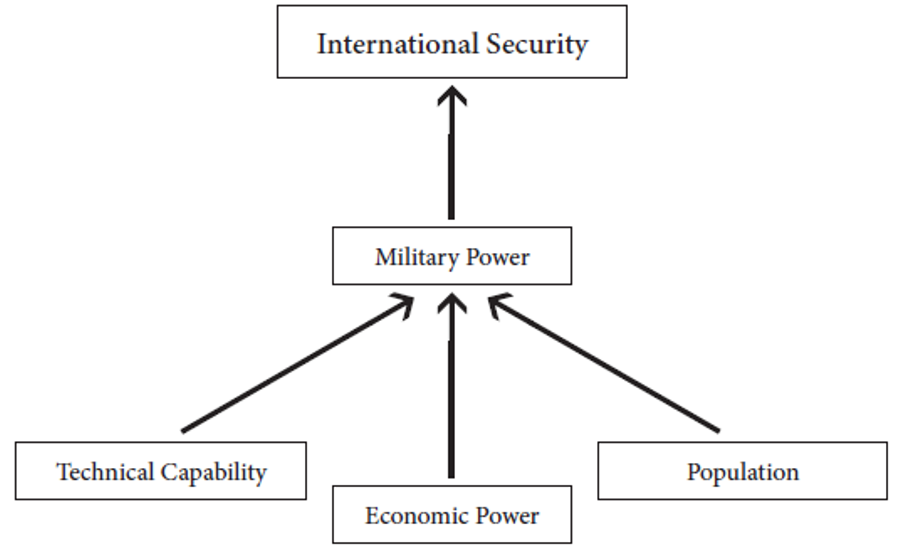

Population and technical capability are important but cannot expand military power by themselves. Observe that, Israel has a relatively small population yet is the most powerful state in the Arabian Middle East. Technical progress is becoming an increasingly significant determinant of military power, but by itself, without economic resources, it cannot expand military power. A state may have the technical capability to design a complicated main battle tank, but building and deploying sufficient numbers of the tank would require the allocation of a significant amount of economic resources. In Figure 2, the main elements of the international security model are outlined.23

Figure 2: International Security Model

In addition to fundamental determinants of military power, there are other factors such as the location of the military conflict and the source and producer of weapons. These can be important determinants of military power for some states and some conflicts.

Location of Military Conflict

Military power of a regional or major power with respect to its enemies can also be affected by the location of the potential conflict. A state’s military force is relatively more powerful closer to its borders. For instance, Russia can be expected to be more powerful militarily in Eastern Europe compared to the U.S.

The relative military power of a state diminishes in proportion to its distance to a potential conflict. Similarly, military force is less powerful with respect to conflicts requiring transportation of men and material over water. The location of the conflict can be especially important when conflicts of long duration that require a large and ongoing logistic support are considered. In the Second World War, the difficulty of supplying German forces deep in Russia is a good historical example.

Source of Weapons

Military power of a regional or major power depends on who supplies its weapons. Major Powers tend to produce their own weapons; France, China, Russia and the U.S. are self-sufficient in this respect. Other major powers and regional powers are not completely self-sufficient. A military power dependent on foreign weapons is vulnerable to the use of the required maintenance supplies of these weapons as a political instrument by those suppliers. Dependence of a state’s military power on foreign sources renders the military power potentially weak.

Policies for Maximizing Security

In order to maximize security, a regional or a major power would aim to be militarily the most powerful in its region; other states in the region should not be able to threaten the state militarily. Note that this view is confirmed in recent years by the behavior of Russia in Europe, of Iran and Israel in the Middle East, and by China in Eastern Asia.

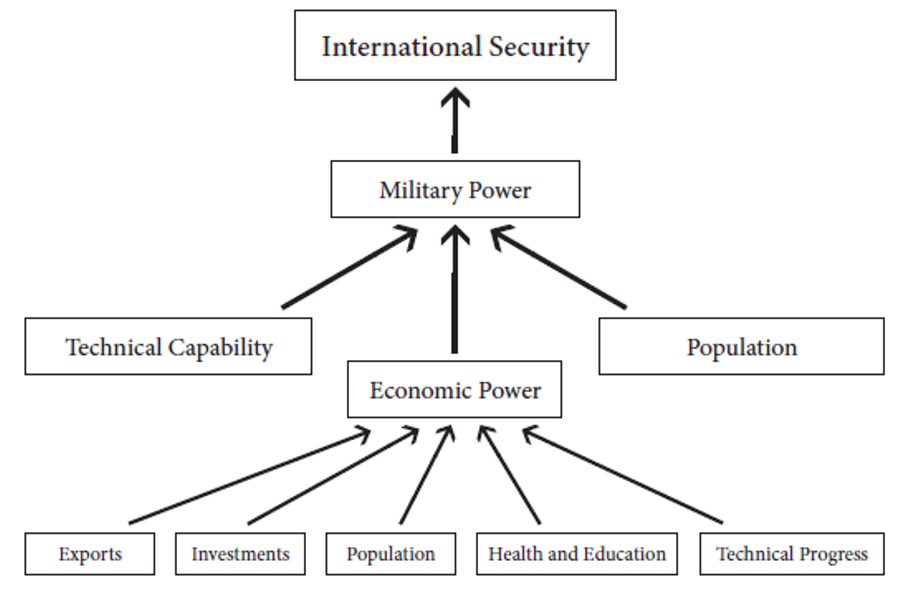

The key elements of the complete integrated model, integrating the economic power and international security models discussed in this article, are illustrated in Figure 3.24 As outlined in this figure, the fundamental determinants of military power of a nation are economic power, technical capability, and population, and among these factors economic power was identified as the key determinant of military power of regional and major powers. While not neglecting technical capability and population, states would follow policies that will expand their economic power in order to maximize their security. A regional or major power would follow policies that enhance, exports, investment, technical progress, and population, health and education, policies that expand economic power. Policies that hamper the growth of economic power would be avoided.

If a state has not accumulated the required economic power that can sustain financing of the most powerful military power in its region, it would follow accommodative and peaceful foreign policies and concentrate on policies for expanding economic power

It should be recognized that the policies mentioned above are challenging to follow. Raising investment may require restricting private consumption. Expanding exports in competitive world markets requires products as attractive as those that other states are providing, but at lower prices. The South Korean auto industry was able to offer cars as desirable as the existing world favorites, but at lower prices. Maintaining technical progress in a rapidly changing technical world is a difficult task. Augmenting and encouraging the growth of population may prove to be difficult or impossible. The Kindergeld (money for children) policy of Germany has revealed that even financial rewards may not lead to an expansion of population.

If there are no underemployed resources, accumulation of military power implies the reduction of civilian consumption and investment. However, there may be military projects that might increase the technical progress of a nation and thereby its economic and military power. These types of military projects can be identified and emphasized while accumulating military power. Military avionics and digital electronic technologies are examples of areas that could spin off applications in civilian industries and enhance the technical productivity of a nation.

If a state is suffering from underemployment of its resources, it can accumulate military power without reducing consumption or investment. The U.S. was underemployed because of the lingering effects of the Great Depression of the early 1930s before joining the Second World War. The consequent war induced the rise in military production, eliminated underemployment and accelerated technical progress.

If a state has not accumulated the required economic power that can sustain financing of the most powerful military power in its region, it would follow accommodative and peaceful foreign policies and concentrate on policies for expanding economic power. After a state has the strongest military power, it could employ military force for achieving international policy objectives that would increase its security.

In the anarchic international system, a significant rise in the economic and military power of a regional and major power will not be accommodated by other states. The rise in the power of a state would be perceived as a dilution of their economic and military power

A regional or major power would employ its military power and engage in war in such a way that there will be no rise in the interest rates or depreciation of its national currency relative to other currencies. High-cost and long-lasting wars would be avoided, especially wars that result in high numbers of casualties. High-cost wars would undermine the state’s authority and credibility and lead to domestic political instability which could hamper the state from achieving its security objectives. Rather than using military power and war, a state would seek political solutions to high-cost security issues.

If a state is not a nuclear military power, it would first aim to become a latent nuclear power, a state with a completely developed nuclear power industry with uranium enrichment facilities and reactors but without nuclear weapons. The all-out effort to become a nuclear power at the start would provoke existing nuclear powers and they would try to stop any fledging nuclear power. Nuclear powers do not wish to dilute their nuclear power by allowing other nations to go nuclear. Good examples of latent nuclear powers are Germany and Japan. Both of these nations have the capacity to quickly build effective nuclear weapons systems, nuclear weapons and the means of delivery.

The rise in the economic and military power of a state in a region will threaten the security of other states in this region. These states would try to contain or scuttle the rise by attempting to expand their economic and military power and may form an alliance against the rising state. Furthermore, these states may be joined by other states which are not geographic members of the region but have an interest in containing the rising state.

In the anarchic international system, a significant rise in the economic and military power of a regional and major power will not be accommodated by other states. The rise in the power of a state would be perceived as a dilution of their economic and military power. A case in point is the rise of Iraq and its invasion of oil rich Kuwait, and the following First Gulf War and alliance that was formed that pushed the Iraqi military force out of Kuwait. Although the security objective of trying to be the most powerful economic and military power in a region remains valid, achieving that status is a difficult objective.

Conclusion

In this paper, a theoretical framework for explaining and predicting the effect of economic power on security of a major or regional power was presented, and some of its policy implications were discussed. To provide some empirical evidence, historical developments that are related to the ideas expressed in theoretical models were discussed. The complete model, the theoretical framework, introduced is comprehensive, and yields plausible predictions. There are no well-known theoretical frameworks that combine economic and military power and security explicitly as in the model introduced in this paper. With the model, the impact of various economic developments can be analyzed and their effect on security can be determined. For example, the model reveals the impact of a rise in exports. The rise in exports increases the economic power, and increases in economic power allow an expansion in military power and a rise in military power increases security.

The theoretical ideas expressed in this paper can be analyzed further. For instance, in the complete security model causal relations are assumed to be unidirectional. In more detailed formal models, bidirectional casual relations can be introduced. By allowing for such refinements, the model can be made more realistic, but such innovations would complicate the straightforward complete model which is able to yield interesting predictions.

Furthermore, various hypotheses that the model postulates can be tested formally. For example, the positive relation discussed between economic power and military power can be examined by employing regression techniques using data specifically for regional and major powers. Short of such major extensions, an effort was made in this direction by citing some relevant studies that provide such evidence from a variety of states.

Endnotes

- I would like to thank the referees of this journal and John J. Mearsheimer for their comments. All views discussed are my responsibility.

- See, Kenneth N. Waltz, Theory of International Politics, (New York: McGraw-Hill Inc, 1979), pp. 88-93;, Robert Gilpin, War, and Change in World Politics, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), p. 92, John J. Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, (New York: W.W. Norton & Comp., 2001), pp. 29-54, and, G. John Ikenberry, Liberal Leviathan, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011).

- For well-known examples see Waltz, Theory of International Politics; Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics.

- The model at times may be realistic for interpreting and predicting the behavior not only of major and regional powers but of less powerful states.

- Note that the model has both a positive aspect of explanation and a normative character of showing optimal behavior of a major and regional state. See, Milton Friedman, Essays in Positive Economics, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1953), pp. 3-43, for a discussion of positive and normative theories. See also, Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, pp. 11-12, who makes the same point about offensive realist theory.

- This description of a major power is similar to those of Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, pp. 1-28, and Joseph S. JR. Nye, Understanding International Conflicts, (New York: Longman, 2003), pp. 59-86, however, descriptions presented here emphasize the ability of major powers to produce their own weapons.

- Economic and military power of states varies over time. The changes in the distribution of economic and military power of major states during recent centuries are discussed by Ikenberry, Liberal Leviathan, pp. 35-78.The rise of a state to a major power status is attributed to the interaction of differential growth rates and anarchy. For a further discussion see, Christopher Layne, “The Unipolar Illusion,” International Security, Vol. 17, No. 4 (Spring 1993), pp. 5-51.

- There are several discussions of growth models emphasizing the role of exports in economic growth. Among the various studies, see the original discussion of Balance of Payments Constrained growth model by Anthony P. Thirlwall, “The Balance of Payments Constraint as an Explanation of International Growth Rate Differences,” Banca Nazionale del Lavoro Quarterly Review, Vol. 3, No. 128 (1979), pp. 45-53, and for an empirical application of this model to the U.S., see H. Sonmez Atesoglu, “Balance of Payments Constrained Growth Evidence from United States,” Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, Vol. 15, No. 4 (1993), pp. 507-514; and for an application to Germany, see H. Sonmez Atesoglu, “Balance of Payments Determined Growth in Germany,” Applied Economic Letters, Vol. 1, No. 6 (1994), pp. 89-91. For the original discussion of the neoclassical growth model see, Robert M. Solow, “A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 70, No. 1 (February 1956), pp. 65-94; Robert M. Solow, “Technical Change and the Aggregate Production Function,” The Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 39, No. 3 (August 1957), pp. 312-320; and for a more recent discussion of this model in a modern macroeconomic text-book see, Robert J. Gordon, Macroeconomics, (Boston: Addison-Wesley, 2012); and John B. Taylor, Principles of Macroeconomics, (Boston: Houghton and Mifflin Company, 2007), pp. 204-226.

- For further discussion and for an empirical application of the Kaldor model to the U.S. see, Atesoglu, “Balance of Payments Constrained Growth Evidence from United States,” pp. 507-514, and for a further comprehensive discussion see, John McCommbie and Anthony P. Thirlwall, Economic Growth and Balance-of-Payments Constraint, (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1994).

- In light of the empirical findings suggesting that technical progress is the main driver of the economy in the neoclassical growth model, this variable rather than basic factors of production was recognized as the most important growth factor. See, for example, Solow, “Technical Change and the Aggregate Production Function,” and Taylor, Principles of Macroeconomics, pp. 204-226.

- There is no widely recognized definition of economic power. In economics, economic power is not a frequently discussed concept. In a conventional modern textbook such as, Robert, J. Gordon, Macroeconomics, economic power is not mentioned. The definition offered here and the model of economic power discussed below can be considered as preliminary.

- Developments in economic power can affect the determinants. For example, a rise in economic power can lead to a rise in technical progress and exports, but here for simplicity such effects are not considered.

- See, John J. Mearsheimer, “The False Promise of International Institutions,” International Security, Vol. 19, No. 3 (Winter 1994/1995), pp. 5-49. For a further discussion of anarchic world order and its implications for state behavior see, Waltz, Theory of International Politics; Kenneth N. Waltz, Man the State and War, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), pp.159-223, and Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics.

- “Israel to Build 5,700 Illegal Settlements: Report,” Anadolu Agency, (April 29, 2018) retrieved from https://aa.com.tr/en/middle-east/israel-to-build-5-700-illegal-settlements-report/1111537.

- For a discussion of complex interdependence, see Nye, Understanding International Conflicts.

- States may go to war motivated by perceived gains according to Gilpin, War, and Change in World Politics, p. 92. Possible potential benefits of war are detailed by Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, pp. 147-152.

- Alternative security approaches are discussed by Benjamin Miller, “The Concept of Security: Should It Be Redefined?” Journal of Strategic Studies, Vol. 24, No. 2 (June 2001), pp. 11-42.

- Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, pp. 46-48.

- Soft Power idea is discussed by Joseph S. Nye, The Paradox of American Power, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002).

- See the role of nuclear weapons with respect to the security of Ukraine and Russia, John J. Mersheimer, “The Case for a Ukrainian Nuclear Deterrent,” Foreign Affairs, Vol. 72, No. 3 (Summer 1993), pp. 50-66.

- For a discussion of a security model emphasizing military and economic power, see H. Sonmez Atesoglu, “Security of Turkey with Respect to Middle East,” Perceptions, Vol. 6, No. 2 (Summer 2011), pp. 99-110.

- There is rigorous empirical evidence suggesting that economic power is a key determinant of military power. Time-series and cross-section empirical analyses using data for various states indicate that in general there is a significant relation between military spending and aggregate economic output. See, Todd Sandler and Keith Hartley, The Economics of Defence, (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1995), pp. 52-72; H. Sonmez Atesoglu, “National Power of Turkey and Other Powers in the Region,” European Security, Vol. 17, No. 1 (2008), pp 33-45; H. Sonmez Atesoglu, “Economic Growth and Military Spending in China,” International Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 42, No. 2 (Summer 2013), pp. 88-100; Justin George and Todd Sandler, “Demand for Military Spending in NATO, 1968-2015: A Spatial Panel Approach,” European Journal of Political Economy, (2017), retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2017.09.002; Justin George, Dongfang Hou, and Todd Sandler, “Asia-Pacific Demand for Military Expenditure: Spatial Panel and SUR Estimates,” Defence and Peace Economics, (2018), retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2018.1434375.

- In the simple flow-chart figure, for simplicity direction of causality is assumed to be unidirectional, from determinants to security. In reality there can be reverse causation, for instance, a rise in military power can affect economic power. A cointegration examination of U.S. time-series data reveals that military spending affects aggregate output, see H. Sonmez Atesoglu, “Defense Spending Promotes Aggregate Output in the United States: Evidence from Cointegration Analysis,” Defence and Peace Economics, Vol. 13, No. 1 (2002), pp. 55-60.

- In this figure, to keep the model straightforward, causality is assumed to be unidirectional from determinants towards international security; however, there can be significant reverse causality among the variables. For example, security objectives reached by using military power may increase economic power.