Turkey’s successful military intervention to preserve Libya’s Government of National Accord (GNA) marks a turning point for the security architecture of the Middle East and North Africa. Turkey’s new capability to project military power far beyond its coastal borders—a paradigm shift enabled by the rise of its defense industry—has made Turkey’s strategic orientation one of the most significant determinants of the region’s geopolitics. How Turkey calibrates the congruence between its hard power instruments and its strategic orientation now constitutes a factor of the utmost consequence for the strategic calculus of the entire Mediterranean basin.

The renowned strategic theorist Carl von Clausewitz noted that war’s “grammar may be its own, but its logic is not.”1 The military means that a country employs in the international arena to achieve its policy objectives, and the manner in which those means function, constitute the grammar of a country’s warfighting capability. It is the country’s strategic orientation in relation to its geopolitical circumstances that provides the logic of the policy objectives of that warfighting capability. In Clausewitzian terms, the transformation of Turkey’s defense industry has enhanced Turkey’s grammar of warfare through the production of new hard power instruments. Turkey’s strategic principles and purposes in relation to its geopolitics, its Clausewitzian logic, will determine Turkey’s use of those hard power instruments and its impact on the regional security architecture.

Turkey’s new expeditionary capability, resting on the twin advancements of increased blue-water capability and the establishment of forward bases, originated as the logical outcome of Turkey’s strategic reorientation resulting from the conclusion of the Cold War. In moving beyond the Cold War framework, Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AK Party) has been guided by the strategic goal of transforming Turkey into an interregional power that will set the terms for a new pattern of connectivity between Europe, Africa and Asia. In so doing, the AK Party seeks to ‘reclaim’ for the Republic of Turkey a foreign policy prerogative exercised by the Ottoman Empire but discontinued after Turkey’s founding following the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, when the fledgling republic’s foreign policy scope was limited by the exigencies of preserving its territorial integrity during the interwar period. Threatened by rising Soviet power in the wider Black Sea region and the Middle East in the aftermath of World War II, the Lausanne orientation informed Turkey’s 1952 NATO accession and persisted through the duration of the Cold War.

In forging an effective strategic logic for Turkey that moves beyond Lausanne, Ankara is presented with the challenge of calibrating the use of its expeditionary hard power to serve its strategic orientation toward establishing a Turkey-centered, interregional connectivity. This calibration entails distinguishing systemic rivals from locally-focused actors and gauging the use of coercive force toward each accordingly. Additionally, the utility of forward bases needs to be assessed on the basis of whether their contribution to maintaining or expanding interregional connectivity warrants the cost of Turkey’s extended expeditionary posture in relation to its productive capacity.

The extent to which Ankara will succeed in building a Turkey-centered connectivity after its success in Libya will depend on the manner in which its post-Lausanne logic guides Turkey’s calculus in these two regions

Turkey’s calibration is occurring in the geopolitical context of two concentric containment arcs: an inner arc in the Eastern Mediterranean and an outer arc roughly corresponding to the 19th parallel north latitude, spanning the G-5 countries of the western Sahel and Sudan. The extent to which Ankara will succeed in building a Turkey-centered connectivity after its success in Libya will depend on the manner in which its post-Lausanne logic guides Turkey’s calculus in these two regions.

The Geopolitical Logic of Turkey’s Strategic Reorientation

Turkey’s robust expeditionary capabilities derive from the build-up of its defense industry over the course of the past two decades, a transformation whose logic extends back into Turkey’s strategic reorientation beginning in the early post-Cold War period. The Soviet Union’s collapse at the Cold War’s conclusion removed the overarching systemic conflict that formed NATO’s raison d’être and the basis of Turkey’s membership. Turkey’s uncertain future role in the alliance necessitated the country’s strategic planners in the early 1990s to contemplate the diversification of Turkey’s security relationships, developing new relationships with regional actors beyond the NATO framework and even relationships outside the U.S. security umbrella.

With a particular concern for Turkey’s Middle Eastern interests, this decade of reassessment was inaugurated by the 1991 Persian Gulf War in which the United States led an ad hoc coalition of 35 nations in Operation Desert Storm to reverse Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait. For Ankara, America’s ‘unipolar moment’ in Iraq carried potentially dire consequences for Turkey’s national interests. With heightened concerns that Turkey could face a flood of Iraqi Kurdish refugees or that Kurdish terrorists could exploit a political vacuum in Iraq, Ankara’s insufficient impact on events near Turkey’s borders highlighted the future possibility that Turkey could be left to fend for itself in the Middle East and the Mediterranean basin.

Within this evolving geopolitical context, Turkey developed its National Military Strategic Concept during General Hüseyin Kıvrıkoğlu’s tenure as Chief of Staff (1998–2002). Turkey’s new strategic outlook called for an ‘active deterrence’ in which military force would be deployed to neutralize threats at their source.2 The National Military Strategic Concept situated this limited power projection posture within the framework of Turkey’s military preparedness to fight ‘two and a half wars’—two conventional inter-state conflicts on Turkey’s southern and western fronts and the simultaneous prosecution of a large-scale counter-terrorism campaign (the ‘half’ war) against the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) terrorist organization.3 The impetus for Turkey’s military industrial transformation was thus nascent within Turkey’s strategic logic.

Turkey’s period of strategic reassessment was punctuated at the onset of the AK Party’s governance by the 2003 U.S.-led invasion of Iraq. The stark reality of a U.S. hard power presence operating directly opposite Turkey’s southern borders, potentially counter to Turkey’s vital national interests, further impelled Ankara’s already established orientation to diversify its security partners; but now the logic of that orientation included a perceived need for the ability to counter adverse consequences of U.S. power in the Middle East through cultivating deeper strategic relationships with Washington’s rivals. Thus, the program to build up the manufacturing capacities of Turkey’s defense industry developed as a correlate of Turkey’s strategic imperative to function geopolitically as an independent actor. In the absence of a coherent NATO framework that treated Turkey as an equal partner in the Middle East, this outcome was a natural progression of the strategic logic that emerged from the Cold War’s conclusion.

The program to build up the manufacturing capacities of Turkey’s defense industry developed as a correlate of Turkey’s strategic imperative to function geopolitically as an independent actor

The current phase of Turkey’s strategic reorientation was ushered in by a decisive series of events that occurred during the 15-month period from spring 2015 to summer 2016. In March 2015, the U.S. started providing air cover and weapons to the People’s Protection Units (YPG), the PKK’s Syrian branch, disregarding Ankara’s protests. Emboldened by its superpower support, Kurdish YPG forces captured the Arab-majority city of Tal Abyad on June 15, 2015; from there, the YPG’s campaign forged a contiguous corridor along the length of the Turkish border east of the Euphrates. Facing the prospect of the YPG extending this corridor westward across the Euphrates, Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan put the international community on notice: “I am addressing the whole world,” Erdoğan declared on June 26, 2015, “We will never allow a state to be formed in northern Syria, south of our border.”4 With the U.S. and Turkey’s other NATO partners turning a deaf ear, Turkey launched Operation Euphrates Shield on August 26, 2016. Capturing the city of Jarabulus and holding a swath of surrounding territory, the operation prevented the formation of a contiguous YPG-controlled region west of the Euphrates.

Operation Euphrates Shield, the first of eventually four separate Turkish operations in northern Syria, represents the first manifestation of Turkey’s new force projection posture resulting from its strategic reorientation. The culmination of Turkey’s strategic re-orientation had actually occurred a month prior, in the immediate wake of the July 15, 2016 failed coup attempt against the government of President Erdoğan. The lack of a robust response from the U.S. and Turkey’s other major NATO allies in support of President Erdoğan and his government was seen in Ankara as an unconscionable breach of trust and cemented Turkey’s resolve to assert itself as an independent regional power. In addition to cultivating deeper relationships with Russia and China, Turkey fast-tracked the development of its domestic defense production capability through the involvement of private companies to achieve the rapid transformation required by Turkey’s current strategic outlook.

Turkey’s blue-water power projection and forward bases are the logical outcome of the progression of Turkey’s strategic reorientation. Although now associated with the Mavi Vatan or ‘Blue Homeland’ concept popularized in the Turkish media since 2016 by former Rear Admiral Cem Gürdeniz, Turkey’s effort to expand its blue-water capabilities reflects a coherent strategic orientation that began during the 1990s and continued with the AK Party’s 2002 assumption of power. Within the AK Party’s first two years, Ankara funded a $3 billion ‘National Warship’ program, known by its Turkish acronym MİLGEM, to expand Turkey’s capability to deploy naval forces far from its coastal waters. At the September 2011 commissioning ceremony of MİLGEM’s first surface combatant, the Ada-class TCG Heybeliada, then Prime Minister Erdoğan clearly delineated Turkey’s blue-water aspirations, defining Turkey’s national interests as “residing in the Suez Canal, the adjacent seas, and from there extending to the Indian Ocean.”5 The expansive reach of the maritime ambitions articulated by Erdoğan is entirely consistent with the logical trajectory of Turkey’s strategic reorientation toward interregional connectivity. It moreover demonstrates that Turkey’s development of blue-water capabilities was not solely a response to Eastern Mediterranean events such as the 2010 and 2011 natural gas discoveries off the respective coasts of Israel and Cyprus or Turkey’s severance of maritime security cooperation with Israel in the wake of the 2010 Mavi Marmara incident. Indicative of Ankara’s wider blue-water agenda, Turkey opened 26 embassies in Africa from 2010 to 2016.6 It also made parallel efforts in the Indo-Pacific through commercial and defense initiatives with Pakistan and Malaysia.

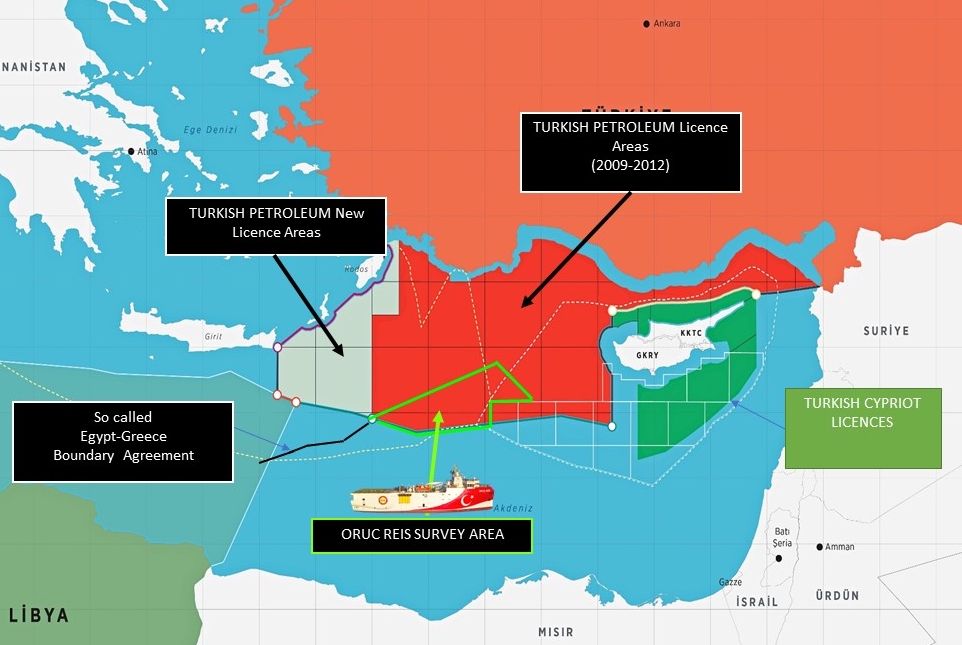

The map shows the region in which the Oruç Reis Research/Survey vessel is carrying out its seismic study activities, within the maritime boundaries that Turkey reported to the UN in the Eastern Mediterranean, August 11, 2020.Ministry of Foreign Affairs / AA

In March 2012, then Turkish Navy Commander Admiral Murat Bilgel declared Turkey’s naval objective was “to operate not only in the littorals but also on the high seas,” identifying the Turkish Navy’s goals for the coming decade as “enhancing sea denial, forward presence, and limited power projection capacity.”7 In line with these goals, Turkey’s program to develop forward bases soon followed, resulting in a December 2014 agreement between Ankara and Doha for the forward deployment of Turkish forces in Qatar and the April 2016 opening of Turkey’s $39 million Tariq bin Ziyad base. Intended to house 3,000 Turkish ground forces plus units from the Turkey’s naval, air and special operations forces, the September 2019 agreement to expand the Qatar-Turkey Combined Joint Force Command in Doha will likely see the stationing of 5,000 Turkish military personnel.8

With the addition of the Mogadishu base, Turkey has established Sea Lines of Communication extending from its Mediterranean coast through the Red Sea-Gulf of Aden corridor to the Horn of Africa, and from the Horn to Qatar in the Persian Gulf

A year and half after Turkey opened its Qatar base, then Turkish army Chief of Staff and current Turkish Defense Minister Hulusi Akar officially opened Turkey’s military facility in Mogadishu, Somalia on September 30, 2017.9 Turkey’s $50 million, four square km Mogadishu base is its largest training facility outside Anatolia, expected to train 10,000 Somali troops.10 The Turkish military is able to house assets there for its own naval, air and ground forces. Turkey’s base provides Ankara with a position reasonably close to the Gulf of Aden, the eastern entry into the Red Sea critical for the operation of the Turkey-Qatar partnership.

With the addition of the Mogadishu base, Turkey has established Sea Lines of Communication (SLOCs) extending from its Mediterranean coast through the Red Sea-Gulf of Aden corridor to the Horn of Africa, and from the Horn to Qatar in the Persian Gulf. The TCG Heybeliada and the three other MİLGEM-produced Ada-class corvettes provide critical capabilities to service Turkey’s new Mediterranean-to-Mogadishu and Mogadishu-to-Qatar SLOCs. Each Ada-class corvette has an endurance of 10 days operating autonomously and 21 days with logistical support. With a range of 3,500 nautical miles (nm) at 15 knots,11 these vessels would be able to travel the 3,134 nm sea distance between Turkey’s Mersin port and Mogadishu in 8.6 days,12 and cover the 2,356 nm sea distance between Mogadishu and Qatar in 6.1 days. MİLGEM’s follow-on phase will augment this capacity with the production by 2023 of four larger “İ”-class frigates based on the Ada-class design and equipped with ATMACA attack missiles.13

In the Mediterranean, Turkey is on the verge of a similar strategic breakthrough with the establishment of forward bases in Libya—an air power deployment at the re-captured al-Watiyah air base, located 27 km from the Tunisian border, and a reported Turkish naval base in the coastal city of Misrata under Government of National Accord (GNA) control.14 Turkey’s first Mediterranean forward basing beyond North Cyprus is a consequence of its successful military intervention on behalf of the GNA in accordance with the ‘Security and Military Cooperation’ agreement signed by Ankara and Tripoli on November 27, 2019 along with a ‘Delimitation of Maritime Jurisdiction Areas in the Mediterranean’ agreement. The framework for the two Turkey-Libya agreements was laid a year earlier during the November 5, 2018 deliberations conducted in Tripoli by Hulusi Akar,15 thirteen months after the defense minister opened Turkey’s military base in Mogadishu.

Turkey’s purpose in declaring its maritime border with Libya, according to the December 1, 2019 public statement of Turkey’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs,16 was to pressure the international community and the Eastern Mediterranean countries to devise an equitable settlement of the region’s maritime boundaries upon which Eastern Mediterranean offshore energy development depends. Irrespective of these issues, Turkey also confronts the possibility that joint action by the Hellenic and Egyptian navies in the event of hostilities could close off the Mediterranean to Turkey by forming a maritime cordon sanitaire from the outer islands the Dodecanese (Rhodes, Karpathos, Kasos) to Crete and then to the North African coast at the Eastern Libya/Western Egypt border region. The establishment of a naval base on the Libyan coast therefore forms a strategic desiradatum for Turkey to counter this contingency.

Turkey’s soon-to-be-operational, light aircraft carrier the TCG Anadolu, a landing helicopter dock based on Spain’s Juan Carlos I-class design, will similarly contribute to preserving Turkey’s freedom of navigation in the Mediterranean. As an amphibious assault ship, it will be able to transport a 1,000 troop battalion along with 150 vehicles, including battle tanks, for a marine landing.17 Traveling at 10 knots, the TCG Anadolu will be able to traverse the 1,186 nm sea distance from Izmir to Tripoli, Libya in 4.9 days.18 A blue-water power projection vessel par excellence, the TCG Anadolu will considerably augment Turkey’s efforts to break out of its strategic isolation in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Turkey’s New Hard Power and the Search for a Logic beyond Lausanne

The most noted articulation of Turkey’s role as the arbiter of new inter-regional connectivity was the 2001 publication of Stratejik Derinlik (Strategic Depth) by former academic Ahmet Davutoğlu, who went on to serve as Turkey’s foreign minister from 2009 to 2014 and then as prime minister until 2016. During Davutoğlu’s tenure as foreign minister, Turkey promoted its strategic reorientation toward interregional connectivity with a policy dubbed ‘zero problems with neighbors’ expressing Turkey’s aspiration of “creating a zone of peace and stability, starting from her neighbors.”19 Placing Turkey’s soft power resources at the forefront of its approach, the policy emphasized that “Security for all, political dialogue, economic interdependence and cultural harmony are the building blocks of this vision.”

Continuing the same approach throughout 2019, Turkey sent four Turkish exploration ships and drill ships, along with their naval escorts, to operate in the disputed waters of the Eastern Mediterranean

While promising at the outset, the policy faltered on its counter-productive execution and the intransigence of several Turkey’s neighbors, leaving Ankara isolated in the region by 2014. In that year, Turkey watched a hostile government in Egypt entrench its power, an Iranian-Hezbollah military intervention in neighboring Syria (to be followed by Russia’s 2015 intervention), the launching of the Egyptian and Emirati-backed military campaign of General Khalifa Haftar in Libya, and the outbreak of the Israel-Hamas Gaza War. With its soft power tools seemingly ineffective to influence the outcome of these and other events, Turkey would soon change tack, opting for the use of hard power instruments in the Middle East and Mediterranean basin, as it charted a new strategic course following the events of July 15, 2016.

Calibrating a precise congruence between its new hard power instruments and its post-Lausanne strategic orientation requires Turkey to prevent the hardening of a containment arc in the Eastern Mediterranean by distinguishing systemic rivals, such as France and the UAE, from neighbors, such as Greece and Israel, whose antagonisms with Turkey remain fundamentally local. Turkey’s systemic rivals view Turkish connectivity as a threat to their national interests, whereas Turkey’s neighbors do not. The coalescing of Turkey’s systemic rivals with its neighbors to form a containment arc in the Eastern Mediterranean20 reveals an incongruence between Turkey’s use of hard power instruments and its post-Lausanne logic of interregional connectivity.

Attempting to defend Turkey’s national interests in the Eastern Mediterranean and the rights of Turkish Cypriots as the constitutional co-owners of Cyprus’s natural gas, Ankara engaged in a series of hard power actions during 2018 and 2019 that have worsened Turkey’s position by catapulting France to the center of the Eastern Mediterranean dispute, markedly increasing the EU’s adversarial posture. As a result of Turkey’s February 2018 naval action to prevent an Eni drillship from reaching its destination in Cypriot waters,21 the Italian energy company partnered with French energy giant Total in all seven of Eni’s licensing blocks issued by the government of South Cyprus. Continuing the same approach throughout 2019, Turkey sent four Turkish exploration ships and drill ships, along with their naval escorts, to operate in the disputed waters of the Eastern Mediterranean.

Viewed as an escalation of Turkey’s gunboat diplomacy, France signed an agreement to service its warships at the Mari naval base in South Cyprus22 and conducted a four-day naval exercise off Cyprus’s southern coast with its Cypriot and Italian partners.23 France’s naval presence in Cypriot territorial waters is a policy achievement for the South Cyprus government, which seeks to translate France’s economic stakes in Eastern Mediterranean energy and systemic rivalry with Turkey into a form of security guarantee.

France maintains a naval base in the UAE and has partnered with the UAE in support of General Haftar’s Libyan National Army forces against the GNA. Turkey’s actions have resulted in a greater opening for the UAE to enter the Eastern Mediterranean dispute,24 as exemplified by Greece’s invitation to the UAE to join its 2019 Iniohos annual joint air force exercise, an ostensibly Eastern Mediterranean-focused exercise with Israel, Italy and the United States.25 Beyond precluding a maritime cordon sanitaire between Crete and Libya, Turkey’s breakout strategy in Libya has contributed little to enhancing Turkey’s ability to employ hard power in the Eastern Mediterranean. The repeated engagement in escalatory confrontation vis-à-vis its neighbors without a follow-on diplomatic pathway toward a just compromise will likely continue to result in no discernible benefit to Turkey.

A precise congruence between Turkey’s use of hard power instruments and its post-Lausanne logic of interregional connectivity, then, suggests the indispensability of Turkey compartmentalizing its antagonisms with local Eastern Mediterranean actors

In the geopolitical context of the Maghreb and Sahel, Turkey’s forward bases in Libya constitute a strategic breakthrough for Ankara’s goal of creating interregional connectivity, cementing Turkey’s status as a major actor in North Africa and enhancing its reach beyond. Turkey’s ascending influence in neighboring Tunisia and Algeria, with the former’s vital Mediterranean ports and the latter’s trans-Saharan highway, position Turkey to play a major role in an emerging nexus of commercial routes that connect West Africa to Europe and the Middle East. Calibrating a precise congruence between Turkey’s new hard power instruments and its post-Lausanne strategic orientation requires Ankara to avoid becoming overstretched when confronting the outer containment arc along the 19th parallel from Mauritania’s capital Nouakchott on the Atlantic coast to Sudan’s Suakin port on the Red Sea.

Turkey has staked an important position in Algeria with $3.5 billion in investments, ranking Turkey among Algeria’s top foreign investors.26 Declaring Algeria “one of our strategic partners in North Africa,” Erdoğan explained, “Algeria is one of Turkey’s most important gateways to the Maghreb and Africa.”27 Yet Ankara’s consolidation of a Turkey-oriented commercial corridor presents several daunting challenges. In contrast to the scale of its Algerian investments, Turkey’s 2019 exports to Algeria totaled a paltry $5.1 million,28 placing Turkey 76th among Algeria’s import markets. In contrast, France is the largest exporter to Algeria after China, earning Paris $3.85 billion in revenue in 2019.29

In the event of Turkey’s further use of hard power instruments in Africa, France could push back against Turkey by utilizing its formidable resources south of the Maghreb. Unlike France’s rather superficial military presence in Libya, Paris maintains a ring of military power around Libya and Algeria with operational facilities in Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger and Chad that bring French hard power to the southern borders of Algeria and Libya, supported by permanent bases in Senegal, Cote D’Ivoire, and Gabon.30

France’s total military expenditure more than doubles that of Turkey, with a 2019 defense budget of $52.2 billion compared to Turkey’s $20.8 billion. While Turkey’s defense budget equals a hefty 2.7 percent of its GDP, France’s much larger outlay constitutes only 1.9 percent.31 France’s spends $800 million annually on Operation Barkhane in the western Sahel alone, and upwards of $1 billion total on military operations in Africa.32 While Turkey need not match France’s defense outlay, its hard power expansion in Africa would require a significantly higher order of magnitude in expenditure than what it has hitherto spent on its expeditionary capability.

Moreover, since Operation Barkhane is a counter-terrorism mission, France may be able to draw deeper European Union support, potentially pitting other European countries against Turkey. If France’s EU partners elect not to assume more burden-sharing in Africa, then France will turn to its Arab Gulf partners, primarily the UAE and Saudi Arabia, for financial support, entrenching the Franco-Gulf States rivalry with Turkey as one of the main drivers of African geopolitics. Already, Turkey’s effort to secure Sudan’s Suakin port as dual-use facility was stymied by Sudan’s 2019 change of government financially backed by the UAE. Franco-Emirati coordination across the 19th parallel from Nouakchott to Suakin would present a formidable challenge.

How the congruence between Turkey’s commercial connectivity and its extended expeditionary posture unfolds will shape the course of Turkey’s foreign relations and greatly influence the future contours of the security architecture of the Middle East and the Mediterranean basin

Conclusions

As the Turkish Navy’s 2015 Strategy Paper points out, 87 percent of Turkey’s trade comes through its commercial maritime ports.33 With most of its trade traversing the Eastern Mediterranean, Turkey’s interests are not served by destabilizing the security of the Eastern Mediterranean maritime domain. The development of any future Africa-to-Turkey or Indian Ocean-to-Turkey commercial corridors faces the ineluctable necessity of a peaceful Eastern Mediterranean maritime commons.

A precise congruence between Turkey’s use of hard power instruments and its post-Lausanne logic of interregional connectivity, then, suggests the indispensability of Turkey compartmentalizing its antagonisms with local Eastern Mediterranean actors. By de-coupling the Eastern Mediterranean from Turkey’s wider systemic competition with France and the UAE, Ankara has the opportunity to provide Turkey and its neighbors an off-ramp from increasing escalation and a pathway to an equitable maritime boundary settlement. Egypt, which exhibits characteristics of both a regional antagonist and a systemic rival, poses an even greater challenge for the calibration of Turkish policy. In the Sahel, the extension of Turkey’s expeditionary posture cannot outpace the development of its commercial relations in Africa. Failure to calibrate this quantitative congruence could fatally overstretch Turkey’s position.

Turkey’s strategic reorientation was over a generation in the making; the effort to establish a Turkey-centered interregional connectivity will require a similar time horizon. Ankara’s attempt to develop forward bases in support of that effort has become a permanent feature of Turkey’s geopolitics. How the congruence between Turkey’s commercial connectivity and its extended expeditionary posture unfolds will shape the course of Turkey’s foreign relations and greatly influence the future contours of the security architecture of the Middle East and the Mediterranean basin.

Endnotes

1. Carl von Clausewitz, On War, translated and edited by Michael Howard and Peter Paret, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976), p. 605.

2. Can Kasapoğlu, “Turkey’s Growing Military Expeditionary Posture,” Jamestown Foundation Terrorism Monitor, Vol. 18, No. 10 (March 15, 2020), retrieved from https://jamestown.org/program/turkeys-growing-military-expeditionary-posture/.

3. Şükrü Elekdağ, “2 1/2 Wars,” Republic of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs Center for Strategic Research (SAM), (March-May 1996), retrieved from http://sam.gov.tr/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/SukruElekdag.pdf.

4. Sevil Erkuş, “Erdoğan Vows to Prevent Kurdish State in Northern Syria, as Iran Warns Turkey,” Hürriyet Daily News, (June 27, 2015), retrieved from https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/erdogan-vows-to-prevent-kurdish-state-in-northern-syria-as-iran-warns-turkey-84630.

5. Michaël Tanchum, “Sino-Saudi Red Sea Alignment Presents Opportunity for Turkey-China Cooperation,” Turkish Policy Quarterly, (April 7, 2017), retrieved from http://turkishpolicy.com/blog/20/sino-saudi-red-sea-alignment-presents-opportunity-for-turkey-china-cooperation.

6. Leaders, “The New Scramble for Africa,” The Economist, (March 7, 2019), retrieved from https://www.economist.com/leaders/2019/03/07/the-new-scramble-for-africa.

7. Michaël Tanchum, “A New Equilibrium: The Republic of Cyprus, Israel, and Turkey in the Eastern Mediterranean Strategic Architecture,” Peace Research Institute of Oslo (PRIO), Occasional Paper Series 1, (2015), p. 10.

8. Stasa Salacanin, “Turkey Expands Its Military Base and Influence in Qatar,” The New Arab, (September 10, 2019), retrieved from https://english.alaraby.co.uk/english/indepth/2019/9/10/turkey-expands-its-military-base-and-influence-in-qatar.

9. “Turkey Opens Biggest Overseas Military Base in Somalia,” Daily Sabah, (September 30, 2017), retrieved from https://www.dailysabah.com/politics/2017/09/30/turkey-opens-biggest-overseas-military-base-in-somalia.

10. Harun Maruf, “Turkey Gives Weapons to Somali Soldiers,” Voice of America, (January 5, 2018), retrieved from https://www.voanews.com/a/turkey-gives-weapons-to-somali-soldiers-/4193724.html.

11. “National Ship TCG Heybeliada Introduced to the Press,” Defence Turkey, Vol. 6, No. 31, (2012), retrieved from https://www.defenceturkey.com/en/content/national-ship-tcg-heybeliada-introduced-to-the-press-659.

12. Calculations performed using “Sea Route & Distance” [Calculator], com, retrieved from http://ports.com/sea-route/port-of-mogadishu,somalia/port-of-ras-laffan,qatar/.

13. “Frigate Projects,” Turkish Naval Forces, (February 20, 2019), retrieved from https://www.dzkk.tsk.tr/icerik.php?dil=0&icerik_id=76.

14. “Turkey in Talks to Use Two Libya Military Bases,” Yeni Şafak, (June 15, 2020), retrieved from https://www.yenisafak.com/en/world/turkey-in-talks-to-use-two-libya-military-bases-3532124.

15. Meryem Göktaş, “Turkish Defense Minister Holds Official Visits in Libya,” Hürriyet Daily News, (November 6, 2018), retrieved from https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkish-defense-minister-holds-official-visits-in-libya-138612.

16. Hami Aksoy, “Statement of the Spokesperson of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Mr. Hami Aksoy, in Response to a Question Regarding the Statements Made by Greece and Egypt on the Agreements Signed With Libya on the Maritime Jurisdiction Areas,” Republic of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs, (December 1, 2019), retrieved from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/sc_-73_-yunanistan-ve-misir-aciklamalari-hk-sc.en.mfa.

17. Michaël Tanchum, “Turkey’s New Carrier Alters Eastern Mediterranean Energy and Security Calculus,” The Turkey Analyst, (January 29, 2014), retrieved from https://www.turkeyanalyst.org/publications/turkey-analyst-articles/item/84-turkey

%E2%80%99s-new-carrier-alters-eastern-mediterranean-energy-and-security-calculus.html.

18. Calculations performed using “Sea Route & Distance” [Calculator], com.

19. “Policy of Zero Problems with our Neighbors,” Republic of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs, retrieved from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/policy-of-zero-problems-with-our-neighbors.en.mfa#:~:text=In%20this%20context%2C%20the%20discourse,them%20as%20much%20as%20possible.

20. Michaël Tanchum, “Europe: One Side of the Eastern Mediterranean Fault Lines,” European Council for Foreign Relations (ECFR), (May 2020), retrieved from https://www.ecfr.eu/specials/eastern_med/europe.

21. “ENI Ship Blocked off Cyprus Leaves,” ANSA, (February 23, 2018), retrieved from https://www.ansa.it/english/news/business/2018/02/23/eni-ship-blocked-off-cyprus-leaves-3_3c4d2077-f068-4847-b5ed-d77f9ac4fad4.html.

22. “Cyprus, France Reportedly Agree on Use of Naval Base,” Ekatherimin, (May 16, 2019), retrieved from https://www.ekathimerini.com/240536/article/ekathimerini/news/cyprus-france-reportedly-agree-on-use-of-naval-base.

23. Annette Chrysostomou, “Cyprus, France, Italy in Joint Naval Exercise,” Cyprus Mail, (December 11, 2019), retrieved from https://cyprus-mail.com/2019/12/11/cyprus-france-italy-in-joint-naval-exercise/.

24. On the UAE’s prior efforts, see Michaël Tanchum, “UAE Moves Closer to Israel, Greece and Cyprus, Bolstering Egypt’s Regional Role,” Hürriyet Daily News, (April 1, 2017), retrieved from https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/uae-moves-closer-to-israel-greece-and-cyprus-bolstering-egypts-regional-role--111489.

25. Anna Ahronheim, “Israel Air Force in Greece as part of Iniohos 2019,” The Jerusalem Post, (April 8, 2019), retrieved from https://www.jpost.com/Israel-News/Israel-Air-Force-in-Greece-as-part-of-Iniohos-2019-585993.

26. “Relations between Turkey-Algeria,” Republic of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs, retrieved from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/relations-between-turkey%E2%80%93algeria.en.mfa.

27. “Turkey, Algeria Aim for $5 Billion Trade,” Hürriyet Daily News, (January 27, 2020), retrieved from https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkey-algeria-aim-for-5-billion-trade-151454.

28. Access to macroeconomic and financial data, “Algeria, Exports,” International Monetary Fund,

retrieved from https://data.imf.org/?sk=9D6028D4-F14A-464C-A2F2-59B2CD424B85&sId=151449

8277103; “Algeria, Imports,” International Monetary Fund, retrieved fromhttps://data.imf.org/?sk

=9D6028D4-F14A-464C-A2F2-59B2CD424B85&sId=1515619375491.

29. “Algeria, Exports,” International Monetary Fund; “Algeria, Imports,” International Monetary Fund.

30. État-major des armées, “Carte des Opérations et Missions Militaires,” Republic of France Ministry of Defense, (July 2, 2020), retrieved from https://www.defense.gouv.fr/operations/rubriques_complementaires/carte-des-operations-et-missions-militaires.

31. “Military Expenditure by Country, in Constant (2018) US$ m., 1988–2019,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, retrieved from https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/Data%20for%20all%20countries%20from%201988%

E2%80%932019%20as%20a%20share%20of%20GDP.pdf.

32. “A Review of Major Regional Security Efforts in the Sahel,” United States Department of Defense Africa Center for Strategic Studies, (March 4, 2019), retrieved from https://africacenter.org/spotlight/review-regional-security-efforts-sahel/.

33. “Türk Deniz Kuvvetleri Stratejisi,” Republic of Turkey Turkish Naval Forces, (2015), retrieved from https://www.dzkk.tsk.tr/data/icerik/392/DZKK_STRATEJI.pdf, p. 21.