Introduction

It is appropriate to begin this analysis with a historical account of the major actors in the migration to and from Libya. The first of these is Libya, even though there are many actors within the country itself perpetrating the crimes of exploiting the plight of the migrants who arrive in their territory. The actors within Libya include the many splinter militia groups participating in the lucrative slave business developing in that country; as well as the Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) who claim that they are involved in Redemption Missions to save the victims of human trafficking to Europe and other countries of the world. The last of the actors in Libya are the contesting powers, one of which is the Government of National Accord (GNA) recognized by the United Nations and the international community, and her major opposition, the government of Khalifa Haftar who has continuously challenged the authority of the GNA. In terms of international reckoning, it may be argued that trafficking in persons is now the third most profitable business for organized crime after the drugs and arms trade. Indeed, the phenomenon is inherently detrimental and violates fundamental human rights to life, liberty, dignity, and freedom from discrimination. The result of this is that migrants who fall into the hands of these militants become prey to being maltreated misled or could be sold off as slaves, a new trend of the migrant problem now manifesting in Libya. From the point of view of economics, Libya remains the supplier through its self-designed detention camps and facilities which number about 30-35 depots at various centers in the country.1

However, not all migrants in Libya are Libyans, they come from the West African zone, of which Nigeria is the main source of migration. There is no doubt that countries such as Niger, Chad, Ghana, and Cameroon have their share of the problem, yet Nigeria becomes a player because of its large and adventurous population, in not just West Africa but the continent as a whole. Thus, Nigeria’s role in the supply chains is run and consciously established not just because some migrants ignorantly found themselves in such conditions but unfortunately the successful migrants who found their ways through to Europe keep sending encouraging messages home of their exploits across the Mediterranean Sea to new found lands in Europe. Even though they are informed of the risks involved, their belief and contention are that everything in the world involves an amount of risk, therefore without venture, no success can be achieved. There are many categories of these migrants from Nigeria. Some are mature men with families who are just tired of their poverty-stricken situations and want to try other sources of income. Others are young men who freshly graduated from universities and facing an unemployment situation which makes them feel dejected in society. These categories are bound to take any length of risk to ensure they succeed in life. There are equally young men and women who are not educated at all, or with a low-level education, such as Primary School or Secondary School Leaving Certificates but are equally ambitious. Of the females, a considerable percentage who take such risks have been led into prostitution cartels which are well established in trafficking youngsters as sex workers to various parts of Europe, with Italy as the most established destination. These, therefore are the actors from the supply end of the chain.

Italy is the stronghold and main target of the African illegal migrants who risk their lives to cross the Mediterranean Sea usually in boats or on ships that are mechanically not certified for such seafaring

The main receiving point in this chain is Italy whose link to Libya is historically traceable to its colonization of the African country before it gained its independence in 1951. Moreover, this linkage goes back in time to even pre-colonial years, when the North African countries generally have equally served as a source of migration point of exporting not just goods and services but of human beings. Italy is the stronghold and main target of the African illegal migrants who risk their lives to cross the Mediterranean Sea usually in boats or on ships that are mechanically not certified for such seafaring. The calculation is that once they get to Italy, they can connect to other European countries like Spain, Greece, Austria, Sweden, Malta, Cyprus, France, Netherlands, Belgium, and others. They can start with menial jobs, initially, and then make progress to other better placements with time. Italy, the major European actor in the migration to and from Libya is also a member of the EU. This brings us to the next major actor in the migration to and from Libya, the EU.

The EU represents one in a series of endeavors to integrate Europe since the end of WWII in 1945. After a thorough examination by a working party of legal and linguistic experts, the treaty of the EU was formerly signed by foreign and finance ministers at Maastricht in February 1992.2 Twenty-two EU member states and four non-European countries participate in the Schengen area of free movement, which allows individuals to travel without passport checks. The EU has also taken steps to develop common foreign and security policies and has sought to build common internal security measures.3

It is actually in these areas of the EU policies that border on transnationalism and security issues, that connects this work to the illegal migration in Libya and further into the EU countries that participate in the Schengen Area of free movement. It is of utmost concern that the fears of the EU on these threatening issues of cross-border crime, drug trafficking, international terrorism, and movement of peoples affect the topical issue of illegal migration from sub-Saharan African countries to Libya. The idea or argument is that illegal migrants might be involved in cross-border crimes because of their hopeless unemployment situation. Some of them may equally embark on drug trafficking for survival and often are involved in the movement from one European country to the other in search of improving their means of survival.

It, therefore, translates that an ‘illegal’ immigrant who enters any of these countries over time will potentially be able to connect to almost every other European country. The inflow of migrants and refugees is one of many problems threatening the EU as people frequently arrive at the European shores for different reasons and through different means and channels. They look for ‘legal’ ways to reside in the region, risk their lives to escape from political oppression, war and poverty as well as reunite with their family and benefit from entrepreneurship and education. In 2015 and 2016, the EU experienced an unprecedented influx of refugees and migrants. More than 1 million people arrived in Europe4 through illegal movements, most of them fleeing from the ravages of war and terrorism; and spreading into countries across the EU. This phenomenon has had several negative impacts such as institutional changes, restrictions on legal migration, euro crisis, insecurity, and Brexit on many EU members in areas of security, economy, and boundaries.5

The inefficacy of the EU to face new challenges, like the influx of migrants, poses more pressure on Europe’s economy and by so doing, insecurity and unemployment increase. This then attests that European public policies are becoming completely dysfunctional, not only in terms of implementation of possibilities in concrete situations but also in relation to the fundamental values of the EU, that is integration of the member states. This fall-out implies that what affects one country eventually affects many others. By implication, the illegal migrants that cross the Mediterranean Sea into Italy from Libya still have the opportunity of soon crossing to other European countries.

The Conditionality of Migrants in Libya and the Nigerian Connection

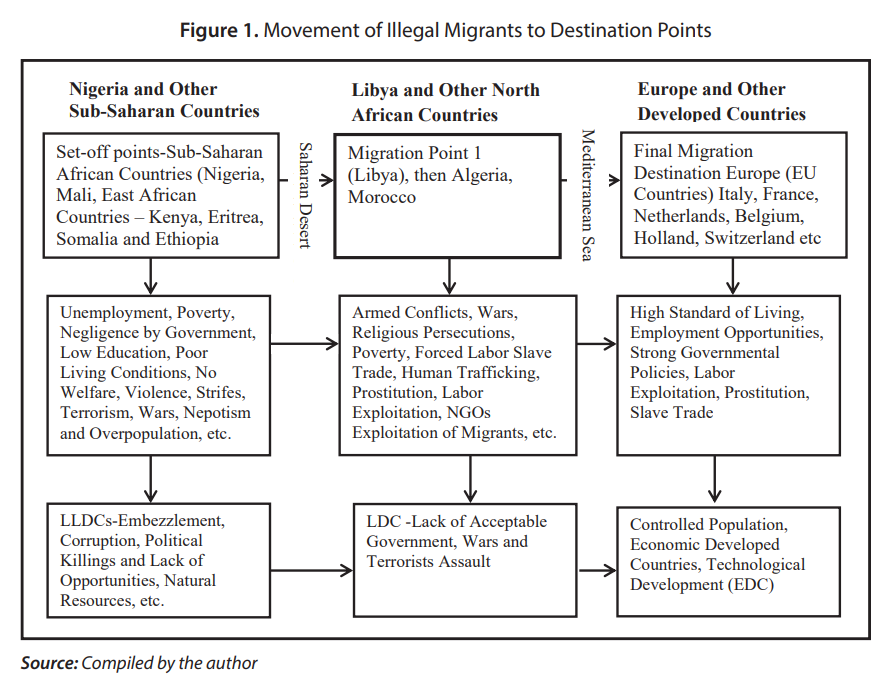

In understanding the conditionality of the migrants that frequently arrive in Libya and eventually become victims of Libyan overlords and manipulations, it is equally necessary to link these victims to the general conditionality of the Least Developed Countries (LDCs) of the world and the Western powers destabilizing these countries. The tendency of those involved in the migration is often men and women of the South-geopolitical zones striving for better lives in the countries of the North, which most European countries provide. The migration tendencies of these men and women could better be imagined by dreams of thousands of poverty-stricken Africans who hope to change their destinies by acquiring better jobs abroad. This brings into reality the manifestations of the North-South dichotomy.6 In the North-South dichotomy, which is often anchored on the dependency theory, the South is considered a zone of poverty and underdevelopment, while the North is comprised of the Economically Developed Countries (EDCs). The argument is that the South is generally dependent on trade, finance, technology, military, and even social consciousness and scholarship of development from the North. Notably, it is believed that the South (and its citizenry) is weak in trusting its own will, strength, and creativity. Manifestly, it is rich in agricultural and mineral resources, yet its citizens cannot utilize the opportunities that abound locally but often prefer to adjust the attitude of settlement for ready-made goods and services; whereas, they could use their initiatives to invest and produce locally before looking for opportunities to travel out to a destination of unknown realities. Other characteristics of the South which may be applied to these migrants and other Africans, who fail to use their initiatives locally, before falling into dungeons and the depths of the Mediterranean, include a high degree of governmental instability, huge external debts arising from trade deficits, corruption and economic mismanagement, low per capita income, high rate of illiteracy, low standard of living and low-life expectancy, food crisis –the persistent problem of starvation and malnutrition, high unemployment, high rate of refugee cases, high rate of conflicts and governmental disorderliness, ethnic problems, the prevalence of political manipulation and corruption, poor health and educational facilities, and lack of theoretical and ideological clarity of development.

The tendency of those involved in the migration is often men and women of the South-geopolitical zones striving for better lives in the countries of the North, which most European countries provide

Clearly, with these hurdles in a region, there is a tendency for people in this southern dichotomy to want to migrate to the zones of the North for better opportunities and livelihood. However, neglecting certain realities, which border on utilizing their initiatives to look within and see how they can better their lives in their locality. Their thoughts capture the major manifestations of the North which is perceived as a productive workshop and a zone of wealth and affluence. The North, the EDCs, or Europe which the migrants are bound to have a high standard of living, high literacy levels, high per capita income, high engagement and mobility of labor, and highly developed transport and communication networks, and quite satisfying social network programs. For sure, the economics of the North is characterized by strength, while that of the South is weakness.7 These manifestations stand at the root of the reasons why Nigerians and other uninformed Africans are ready to risk their lives through the Sahara desert to embark on a journey of the unknown which eventually leads them to the Detention Camps in Libya.

Thus, it may be duly asserted that the drive for survival, dreams of a better life, and the quest to escape poverty, hunger, unemployment, and insecurity among many other reasons is at the root of their ventures to get to Europe, considered to be their promised land. Significantly, the ‘push factors’ often involved in all migration decisions are exemplified in the race for survival. The ‘push factors’ are the harsh economic realities they find in their native countries while the ‘pull factors’ are those attractions promised to them if they ever get to their destinations. While it should be noted that several Nigerians and other West Africans also go through the normal official routes to get to these lofty ambitions of theirs, yet a greater percentage are refused their visa permissions or applications by the embassies or high commissions. Some are rejected completely and made to feel that the end of the road has come and there can be no forward movement. It is when it gets to this point, that they are ready to go through any ‘illegal’ means to beat the official channels to actualize their dreams.

The Nigerian Linkage to the Migration to Libya

Nigeria is one of the largest countries on the continent of Africa, with a total population of 212,568,404 of which 25 percent live in urban areas.8 The country is made up of an estimated 284 ethnic groups with the following considered as the most populous and politically influential: Hausa-Fulani 29 percent, Yoruba 21 percent, and Igbo (Ibo) 18 percent, Ijaw 10 percent, Kanuri 4 percent, Ibibio 3.5 percent, Tiv 2.5 percent. Nigeria is blessed with enormous natural resources such as crude oil, gas reserves, coal, iron ore, bitumen, gold, uranium, tin ore, timber, palm oil, groundnut, cocoa, and fondly referred to as the “giant of Africa.”9

Although, Nigerian illegal immigrants make up a higher percentage due to the country’s high population and the unemployment rate, the root of the wave of migration in reality does not come from a single source

Despite these natural endowments, this same nation is regarded as one of the most impoverished nations on the face of the earth and ranks high in the corruption perception index. This is due to a low standard of living and high poverty level in the midst of plenty. Statistically, it has been reported that more than 60 percent of its population are living on less than $1/day, 23 percent of children were under forced labor in 2000, with the percentage increasing year after year. The rate of infant mortality is high (74.18 death/per 1,000 lives at birth), adult literacy is minimal (66.9 percent), much of the population is highly undernourished, with 80 million having no access to improved sanitation, and 60 million without basic drinking-water resources, a low percentage of births attended to by skilled health personnel and high material mortality rate.10 As earlier noted, the refugees who eventually cross the Sahara and make it to the North African Coast of Libya are mainly from West Africa and some from the horn of East Africa. Prominent among these are Somalia, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Cameroon, Nigeria, Mali, Senegal, and Nigeria.11 Although, Nigerian illegal immigrants make up a higher percentage due to the country’s high population and the unemployment rate, the root of the wave of migration in reality does not come from a single source. Like a flood of tributaries streaming to the mouth of a river, migrants are fleeing en masse from at least a dozen different countries. Shutting off the flow would mean addressing the needs of migrants spanning half of an entire continent. The hurdle is that Libya’s 1,100 miles coastline has effectively become an open border without government forces to monitor these cartels and the victims.

The issue becomes more critical when one considers the overwhelming statistics of trafficking in persons in Nigeria. UNICEF in 2007 estimated that about 8 million Nigerians are at risk of being trafficked each year internally and externally for domestic and forced labor, prostitution, entertainment, pornography, armed conflict, and sometimes ritual killings. A former Minister of State for Justice in Nigeria once had cause to say that some 45,000 Nigerians are trafficked to a foreign land yearly. A recent update shows more than 200 girls in Nigeria are trafficked to Eastern Europe on daily basis.12 In Nigeria, particularly, the deadly terrorist group called Boko Haram in the North East with a network that spreads almost to all of the Northern part of Nigeria has added to the number of migrants seeking safety and escape from deadly attacks by the group. The terrorists have recently sent hordes of Nigerians of all ages across the Sahara, following some of the deadliest attacks on villages on the fringes of the Nigerian border and extending such operations to neighboring countries of Cameroon, Niger Republic, and Chad. Despite the formation of a Joint Commission by these countries to curtail Boko Haram’s activities, peoples’ lives are still subjected to threats and capture leading to slavery or kidnapping through which Boko Haram generates funds from the governments of such states.

Further from Nigeria, there are age-old cartels whose occupation has been trafficking human beings from Nigeria to serve as slaves in Europe, Saudi Arabia, and some other Middle East countries. More facts emerging on the Nigerian illegal immigrants were given by the Assistant Controller in charge of Training and Manpower Development of the Nigerian Immigration Service (NIS). According to Maroof Giwa “no fewer than 10,000 Nigerians died between January and May 2017 alone, while illegally trying to migrate through the Mediterranean Sea and the Saharan desert.”13 It should be noted that of those who manage to survive the race to European countries most end up either in prison or refugee rehabilitation camps.14 In 2019, 26 Nigerian women, some pregnant, while fleeing from hunger and hardship in Libya perished in the Mediterranean Sea. This incidence was anchored by the CNN News report, which also recorded the footage of African men being sold for $400 at a night auction in Libya. This report sparked a global outrage which made the Nigerian government through its House of Representatives and Senate pass bills to quicken the process of bringing back stranded Nigerians from Libya.

As a result, a large number of these migrants were brought back home. The report on these refugees incriminated the NGOs and aid rescuers whom they accused of keeping them forcefully in prisons to demonstrate to UN officials that they were truly working so that they are compensated by international organizations. Another linkage to Nigeria as a major source of migrants to Libya stems from the fact that Nigeria is the most populous country in sub-Saharan Africa itself attracting a lot of other migrants from other West African states. This is to say that a lot of migrants converge in Nigeria before taking off to their emigrational destinations. This is so much the case because Nigeria is the headquarters of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) with its headquarters in Abuja. Within the ECOWAS stipulation, all categories of migrants are allowed from every West African member state to stay in Nigeria for 90 days without any hindrance from the Nigerian Immigration Services (NIS). While some come in legally with their passports stamped for 90 days, a lot more transverse through illegal routes into Nigeria, not just for trading activities but at times, to stay/live permanently in Nigeria.15

According to UNODC (2006) citation index, West Africa is reported as the sub-region from which most of the trafficking in persons originates. In Africa, Nigeria is ranked by far the highest, followed by Benin, Ghana, and Morocco. This shockingly reveals that Nigeria is the center of human trafficking, especially women and children on the continent of Africa. UNICEF (2006) asserted that Nigeria plays a prominent triadic role as a country of origin, transit, and destination for trafficking in persons. Edo, Delta, Cross Rivers, Ebonyi, Oyo, and other states in Southern Nigeria were identified as places with high records of human trafficking. However, human trafficking seems to flourish in most of the frontier States in Nigeria owing to the porous nature of the borders.16 The NAPTIP/UNICEF Situation Assessment of Child Trafficking in Southern Nigeria State (2007) reported that 46 percent of repatriated victims of external trafficking in Nigeria are children, with a female to male ratio of 7 to 3. They are engaged mainly in prostitution (46 percent), domestic labor (21 percent), forced labor (15 percent), and entertainment (8 percent). Internal trafficking of children in Nigeria was also reported to be for forced labor (32 percent), domestic labor (31 percent), and prostitution (30 percent). Boys are mostly trafficked from the southeastern states of Imo, Abia, and Akwa-Ibom to Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, and Congo, while those from Kwara go to Togo and as far as Mali to work on plantations.17

Furthermore, a survey by the National Agency for the Prohibition of Trafficking in Persons and other Related Matters reveal that the major trafficking routes from Nigeria are in Edo, Kano, Kaduna, Sokoto, Katsina, Kebbi, Jigawa, Yobe, Borno, Calabar, and Lagos, and from border areas around Benin, Cameroon, Niger, Chad, Burkina Faso, and Mali.18 In particular, women trafficked as sex workers for European countries and sometimes in the Middle East form a major proportion including those originating from other countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Assessing the whole situation after getting reports that Nigerian NGOs collaborate with the Libyan militias to keep Nigerians at the detention camps, one is in no doubt that, the migrant situation is turning into a vicious circle where even those who are supposed to redeem and bail out their fellow Nigerians now collaborate to keep them as slaves. It is after these incidences came to the light of both the Nigerian Government and the EU/UN that a joint meeting was organized to resolve the migration problem in Libya to prevent the migrants from traveling to Libya. The contention is that NGOs need to present evidence to their sponsors or even financiers that they are catering for these migrants to get money from overseas humanitarian organizations and even churches.

The European Union Involvement and Its Implications

It has been argued that although the EU is not directly involved in the plight of the illegal migrants, certain actions of the union make them complicit, that is to say, the barriers that prevent legal migrants from entering Europe. The argument is that in as much as the EU member nations do not authorize the migrants to embark on such dangerous and illegal migration, they should bear the consequences of their actions. Resultant from such decisions is that the EU is under no obligation to encourage illegal migration into European countries that runs afoul of international legal operations. Thus, its stance to curtail the flow of illegal migrants across the Mediterranean should be checked from the sources of their embarkation, making their collaboration with Libya, Tunisia, and other North African countries essential.

In Nigeria, the deadly terrorist group called Boko Haram in the North East with a network that spreads almost to all of the Northern part of Nigeria has added to the number of migrants seeking safety and escape from deadly attacks by the group

Historically, the involvement of the EU in the illegal migration through Libyan borders can be traced to the days of Muammar Qaddafi when as early as 2008, it agreed to pay Qaddafi $400 million. Italy later redoubled that deal and Qaddafi received an additional $5 billion over twenty years, a financial boost packaged to right the wrongs of colonization on the condition that he kept a tight grip on the border. However, after the funds were delivered to Qaddafi; not much progress was made in the curtailing of illegal migration from the Libyan seaports. Thousands of migrants continued to flood the shores of Italy, Malta, and Greece as well as a disturbing number of corpses, which frequently washed ashore. Somehow, these deals were dissolved over time as Qaddafi could not be held accountable with his iron-clad rule over Libya, for the funds from Europe which effectively helped him to defend his dictatorship.

In 2010, Qaddafi could not hide his racial contempt for the western leaders as he countered their racist arguments with threats that Europe could imminently turn into Africa, filled with African migrants. He warned that Europe ran the risk of turning black from illegal immigrants, pointing out that without his co-operation and the work he has been doing for Europe the situation would be worse. After the death of Qaddafi, the 28-nation EU at a Summit on February 3, 2017, in Valletta, Malta decided to make amends especially with the fragile government in Libya by offering Tripoli £200 million and assistance with the surge of African migration. At this meeting which took place in the sea lane to Italy, where more than 4,500 people had drowned in 2016 alone, they reconsidered the legal and moral implications of allowing Libya’s coastguards to force people ashore by pledging to improve conditions at the migrant camps there.

These two issues, morality and legality were based on the treatment meted out to these migrants and the fundamental values of human dignity and rule of law which was expected of the coastguards in the treatment of the illegal migrants. Other issues revisited by the European Union, thereafter include abuses and torture suffered at the hands of Libyan militias following the death of Qaddafi. It must also be noted that Libyan’s second civil war (2014-2020) triggered by a chain of events after the fall of Qaddafi in 2011 led to widespread disorderliness as militias jostled for position in an all-out war.

African migrants holding banners writing “I’m a refugee! I’m a human being! No for the persecution and harassment of refugees!” as they demonstrate at the headquarters of the UNHRC in Tripoli after guards shot dead six migrants at an overcrowded Tripoli detention facility in October 2021. MAHMUD TURKIA / AFP

African migrants holding banners writing “I’m a refugee! I’m a human being! No for the persecution and harassment of refugees!” as they demonstrate at the headquarters of the UNHRC in Tripoli after guards shot dead six migrants at an overcrowded Tripoli detention facility in October 2021. MAHMUD TURKIA / AFP

The political crisis which continued unabated led to the emergence of two centers of power -a UN-based government in Tripoli now led by Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh as the Prime Minister of the National Unity Government and forces loyal to Khalifa Haftar in the Eastern city of Benghazi. Within this state of conflictual turmoil in Libya between these two power centers, there has been an increase in the Detention Centers of Migrants from other African countries, fleeing insecurity in their own countries and attempting the crossing to Europe. Detention camps in Libya continue to mete out inhuman conditions to illegal migrants who at times are used as human shields against their invading/attacking opponents.

Agenda for Resolution

In order to curb this trending problem, the resolution of the crisis should be tackled from all fronts of the crisis –the source of the supply, the Libyan recipients and collaborators, and the final destination points in Europe, that eventually receive or turn down the migrants. Concerning Sub-Saharan countries such as Nigeria, Ghana, Senegal, East African countries, and others, the governments should track their illegal migrants through proper border patrols. More importantly, governments in the migrant source states should endeavor to address the plight of unemployed youth through the provision of better jobs, building new job/business opportunities, and welfare packages. Improvement in the policies of government can enhance a better understanding of the situations in the country and so curtail the overzealousness of the youths who either get trapped in detention camps or eventually lose their lives in the Mediterranean Seas.

In Libya, the detention camps should be regularly checked by external bodies in order to intervene in the activities of the militias whose actions amount to an abuse of human rights and a reestablishment of the illegal slave trade. The EU also should reconsider their immigration policies, accepting the fact that globalism, globalization, and transnationalism are important concepts that our current modern world must come to accept permanently.

Improvement in the policies of government can enhance a better understanding of the situations in the country and so curtail the overzealousness of the youths who either get trapped in detention camps or eventually lose their lives in the Mediterranean Seas

In the light of these submissions, the UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) should therefore reinforce their cooperation with the International Organization for Migration (IOM) to forge a meaningful instrumentality to check the upsurge of illegal migration from Sub-Saharan African Countries. Economic empowerment to these countries could be stronger legality to follow than just suggesting that migrants should go back to their home countries without any alternatives to offer succor to the migrants. It would be equally important to trail the political development in Libya after the stemming down of the conflicts between the two major groups, to usher in a democratically elected government into the country. As a matter of urgency, this resolution should indeed take into consideration the intervention of more stable governments of the Middle East, especially Turkey and Egypt whose efforts should aim at forging out a cogent plan of action to put a peaceful and egalitarian government in place. Ankara’s military strength and Washington’s retrenchment from the Middle East have eased the way for Turkey’s increasing role in the de-escalation of regional conflicts. It should be noted that in 2019, the Libyan militia leader, General Khalifa Haftar led an army that advanced on Libya’s government with the backing of Russia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The desperate government went door to door in Western capitals, seeking assistance. Most of these Western powers did not care or dare to intervene. It was to Turkey’s credit that it helped to turn back Haftar’s offensive with minimal military investment. By entering these conflicts, Turkey is carving out a niche for itself in this age of great power rivalry. More importantly, Turkey is also an important member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).19 Members of NATO should equally have a role to play in the resolution of the conflict in Libya.

This work has attempted to assess and highlight the interconnectedness of the illegal migration problem in Libya, its impact on the EU, and efforts made to curb this exacerbating problem

Concluding Remarks

This work has attempted to assess and highlight the interconnectedness of the illegal migration problem in Libya, its impact on the EU, and efforts made to curb this exacerbating problem. Given the submissions of the agenda for resolution, it is only reasonable to conclude that an imminent and lasting resolution of the conflicts in Libya and the problem of illegal migrations which affects the major parties Libya, Nigeria, and other Sub-Saharan African countries; and the EU is sine qua non to the attainment of just solutions. More importantly, it would also save the lives of poverty-stricken humans on the Mediterranean Sea, whose energies could be duly invested into other meaningful endeavors. Lastly, it will serve in the long run to reduce the cross-border crimes, associated with immigration problems in the European continent.

Endnotes

1. Ugwumba Egbuta, “The Migrant Crisis in Libya and the Nigerian Experience,” The African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes, retrieved June 21, 2020, from https://www.accord.org.za/conflict-trends/the-migrant-crisis-in-libya-and-the-nigeria-experience/.

2. Solomon Akinboye and Ferdinand Ottoh, A Systematic Approach to International Relations, (Lagos: Concept Publication Press, 2005), p. 197.

3. Akinboye and Ottoh, A Systematic Approach to International Relations, p. 197.

4. Paul Craig, “The United Kingdom, the European Union and Sovereignty,” in R. Rawlings, P. Leyland and A. Young (eds.), Sovereignly and the Law, Domestic, European Union and International Perspectives, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 165-185.

5. Craig, “The United Kingdom, the European Union, and Sovereignty.”

6. Aja Akpuru Aja, Fundamentals of Modern Political Economy and International Economic Relations, (Owerri: Data Globe Nigeria: 1998), pp. 147-148.

7. Aja, Fundamentals of Modern Political Economy and International Economic Relations.

8. See, “Population of Nigeria in Selected Years between 1950 and 2021,” Statistica, retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1122838/population-of-nigeria/.

9. John Campbell, Nigeria: Dancing on the Brink, (Rowman and Littlefield Publishing Group, 2010), p. 45.

10. Consuelo Corradi and Heidi Stöckl, The Lessons of History: The Role of the Nation-States and the EU in Fighting Violence against Women in 10 European Countries, (Sage Publications, 2016).

11. Sam Ohuabunwa, “Leadership and Governance Failures Drive Africa back into Slavery,” The Guardian, (November 4, 2017), retrieved from https://guardian.ng/issue/leadership-and-governance-failures-drive-africa-back-into-slavery/.

12. “‘Child Trafficking’ Information Sheet,” UNICEF, (2007).

13. “Illegal Migration: 10,000 Nigerians Die in Mediterranean Sea, Deserts,” Punch, (May 20, 2017), retrieved from https://punchng.com/illegal-migration-10000-nigerians-die-in-mediterranean-sea-deserts-nis/.

14. Ohuabunwa, “Leadership and Governance Failures Drive Africa back into Slavery.”

15. Ohuabunwa, “Leadership and Governance Failures Drive Africa back into Slavery.”

16. “Fact Sheets on Human Trafficking,” UNODC, (April 2006).

17. “Situation Report/Assessment on Child Trafficking,” UNICEF, (April 2007), pp. 131-136.

18. Egbuta, The Migrant Crisis in Lagos.

19. Aslı Aydıntaşbaş, “Turkey Will not Return to the Western Fold- Ankara’s Assertive Foreign Policy Is Here to Stay,” Foreign Affairs, (May 19, 2021), retrieved from https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/turkey/2021-05-19/turkey-will-not-return-western-fold.