Introduction

“We will not repeat the mistakes made after the Second World War and the Cold War –this time we will seize the opportunity that knocks on our country’s door.”1

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan

The global system has undergone a significant transformation that is pushing Turkey to relocate its international position. It is required to have a comprehensive strategic vision to reposition Turkey in an emerging global order that is still undergoing significant change, strengthen the means to implement this vision, and produce an extensive roadmap concerning how this vision will be accomplished. In this article, we focus on how this strategic vision should take shape in the realm of foreign policy. The emerging multipolar international order both poses risks and presents opportunities, which we describe in the latter parts of this article. Turkey needs to have a grand strategy to eliminate those risks and seize the opportunities.

To build a comprehensive grand strategy, Turkey primarily needs to have a holistic view vis-à-vis the changing dynamics of the current international system. Even though global politics is multipartite, the international order of the future should be tackled with an integral approach. Turkey’s grand strategy should be designed on national, regional, and global levels. If Turkey creates a grand strategy that only focuses on national matters, the challenges it faces could deepen. An approach that focuses only on regional issues and ignores global ones is not valid either. What needs to be done, from the perspective of decision-makers, is to evaluate what Turkey’s strategic orientation should be, who its potential allies and rivals, or adversaries are; where and how challenges may arise and how Turkey can cope with those challenges. Developing a grand strategy is the best way to strategically relocate Turkey under the changing international system. This strategy should take into consideration the distinctive features of the transitional period but should also facilitate adjusting to the structure of the global order that will emerge after the transitional period; it also should be comprehensive enough to actively implement foreign and security policies in ‘strategic regions’ around Turkey to ensure that the country can reach its goals. We propose to create a new period of preparation by understanding the changes that the global system is going through in all its actuality and to protect Turkey’s long-term interests and achieve a solid position for the country in the new system by adapting to the new system in a strong, stable, and active manner. This strong position should be militarily deterrent and effective, and it should be of a scale that can hinder potential threats against Turkey from materializing by mounting a guard against developments in its near abroad.

In the first part of this paper, we explore the distinctive features of the current, dynamic period of fundamental change taking place in the international system. In the second part, the changes and transformations in Turkey’s strategic environment are discussed with a focus on national, regional, and global levels. In the third part, we propose a framework for Turkey’s grand strategy. In the last part, we analyze Turkey’s foreign policy by particularly taking into consideration the ‘strategic belt/regions’ where Turkey operationalizes its strategic priorities following our proposed framework of grand strategy.

The International System: A New Interregnum?

The debates concerning the conceptualization of the structure of the current international system are diverse. While some of the arguments underline the bipolar nature of the international order, taking into consideration the power competition between the U.S. and China,2 others highlight the multipolar character of the international system by focusing on the emerging powers’ impact on regional and international politics. Most of the arguments lay out the changing dynamics of the distribution of power among states while ignoring the complex nature of the global system that has been taking place since the end of the Cold War.

Lack of global leadership is among the characteristic features of the complex nature of the current, inchoate international system

The world has become tenser in ways that reflect not just structural transformation but the emergence of a more competitive attitude. It is a fact that the unipolar system that emerged after the Cold War is over and has given way to an international system characterized by multilayered and diversified polarity. Multilayered polarity, or what we call ‘multilayered multipolarity,’ is a type of international structure that is politically diverse but institutionally interlinked. This situation signals that the American-centric liberal international system is facing a radical challenge. Nonetheless, the end of the unipolar system has not yet brought about another easily identifiable system, the lack of which has caused the emergence of new global and regional issues that make the current international arena more complex than ever before. It is extremely important to understand the nature of the current complexities at the global level that reflects on a new interregnum.

Lack of Global Leadership

Lack of global leadership is among the characteristic features of the complex nature of the current, inchoate international system. The global leadership problem arises on three different levels, the first being the level of heads of state and government. The prominent differences that have emerged between the positions and priorities of political leaders, including leaders of superpowers, over issues such as the economy, security, climate change, international terrorism, discrimination, and individual armament, push leaders away from multilateralism and toward introversion. These differences are deepening regional clashes and delaying solutions to crises.

At the second level, the lack of global leadership problem persists in global governance and international organizations. The United Nations (UN), which is a central fixture regarding global governance, has become a weak organization when it comes to actively taking a role, as a whole, in international crises.3 Instead of taking the initiative in managing crises, the UN has become dysfunctional or acts as a tool of geopolitical competition between great powers. Nor is this governance issue limited to the UN; other global and regional organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) fail to play a proactive role in the management of crises in their fields.

Global trade and finance, the global production network, and the global supply chain significantly differentiate the nascent multilayered system from the previous, trade-only multipolarity

The third dimension of the global leadership problem is the lack of leadership on the axis of states. The U.S., far from actively solving global problems, has turned into an actor that causes problems and has lost its previously assumed position of ‘neutrality’ in many international issues. The problem that the global leadership faces at the state level is not limited to the U.S. A similar criticism applies to the European Union (EU), China, Russia, and other great powers.4 The EU has turned into a group of countries that take decisions on a national scale instead of deciding and acting as a union on many issues. China, an actor with global leadership potential, at least in terms of its vast population and healthy economic indicators, has extensive problems in global leadership, the first being that it appears to have no strong will or purpose in this direction.5 With that said, it cannot be claimed that China has an effective capacity for global leadership.

Multilayered Multipolarity

The second distinguishing feature of the nascent international system is its multilayered polarity. One of the first elements of this fragmented and relatively fragile multipolar structure is the new form of power distribution, which differs in some respects from previous power distribution models.6 The classical multi-polar structure that prevailed in the 19th century served to maintain a perfect balance among the five players in the system.7 Likewise, bipolarity, which was the dominant model during the Cold War, had divisive features to reflect the balance of power between the U.S. and the Soviet Union.8 While the parties of the multipolar balance were positioned near the actors that would ensure the balance, alliance relations had an extremely loose appearance. In the bipolar system, as a necessity, multiple actors lined up on the side of the balancing actors.9 In such a system, alliance relations were more rigid, and transitivity was extremely rare. In the unipolar structure of the post-Cold War period, while the system had a hierarchical appearance in terms of relative power distribution, the actors were generally able to gain a foothold in the context of their direct or indirect relationship with the superpower.10

The unipolar system, in which counterbalancing was costly, did not last long, and this process, which shaped the largely U.S.-led post-Cold War world order, began to erode with the 21st century. However, the security and power rivalries between the poles, which have taken on separate power forms along the global economic and military power axes of the newly shaped 21st century, present an even more fragmented appearance. Despite the elements of inequality between the parties, the absolute and relative power capacities of many actors cause the new era to appear as a hybrid and multilayered polarity. Therefore, the deadlocks and crises in the current order are being reshaped under a new form in the emerging multilayered, multipolar international system.11

The rising powers have grown stronger on the military level in ways that are producing geopolitical results in their regions; with their deterrent and offensive character, they have ignited the developments that will allow rebellion when necessary

From this point of view, the emerging polarity differs in some respects from the multipolarity that preceded it. First, the previous multi-polarity was a world of empires and the colonies that fed them, in which the main actors were the great powers. Second, unlike the 19th century, the economy has become one of the distinguishing features of the present international order and is much more global in scope and interconnected in content. Global trade and finance, the global production network, and the global supply chain significantly differentiate the nascent multilayered system from the previous, trade-only multipolarity. Third, the interaction created by economic interdependence today is not limited to specific geography. Fourth, the old multipolar structure was based on harmony between the European powers; it was built on European diplomacy and European international institutions, which concerned the European balance of power. The new multilayered system is built on a norm divergence in which international organizations are spread out on a global plane. Fifth, the main factor threatening the harmony of classical multipolarity was conventional, territorial conflict between European states. While conflicts between states have decreased over time, conflicts in the new multilayered polarity seem to have diversified and ceased to be conventional.12 In today’s world, the main threats to states come from terrorism, internal turmoil, or health crises –like the COVID-19– rather than attacks from other states.13

Rising Powers

The short-lived American unipolarity gave way to a largely fragmented distribution of power. The most basic features of the rising powers are their diplomatic, economic, and military action, which they deploy to increase their strategic autonomy (more independent foreign policy). In the new multilayered international arena, actors will continue to diversify and deepen their quest to develop their own political, military, and economic mobilization. The global economy is one of the areas where such diversity is best reflected. The new activism in the World Trade Organization, which is centered around Brazil and India, and the search for economic autonomy, have revealed the necessity of sharing the pie among a broader set of actors, as evidenced by the establishment of the G20 in 1999. This new diplomatic activism and the quest to have a greater impact on the global economy tended to expand in the 2000s due to the overlapping strategic agendas of developing countries. For example, the IBSA Dialogue Forum, which consists of India, Brazil, and South Africa, has brought cooperation to the global agenda, not only in terms of economics but also in the political field.

Although the transition between layers in the new security competition is directly related to material power parameters, the most important aspect is that local-scale security competition can create global effects

This expansion was followed by BASIC in 2009 with the gathering of Brazil, South Africa, India, and China. Furthermore, with the establishment of BRICS, consisting of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, the five largest economies outside the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) were brought together, and it became evident that a much deeper structural change was occurring in the global economy and the dynamics of global capitalism. While the five countries in question hold approximately 50 percent of the global foreign exchange reserves, they have eliminated their dependence on foreign aid, and they have begun to lead the way in global economic aid. This economic and political activism was followed by the establishment of MIKTA,14 consisting of Mexico, Indonesia, South Korea, Turkey, and Australia in 2013. The MITKA countries have fortified their positions as effective actors in their regions and have made a significant contribution to regional and global peace and stability; they mostly follow a similar approach in the face of international problems.

Given their economic vitality and expansion, the rising powers have begun the process of repositioning themselves. Thus, the emerging powers are both transforming the global economy and creating a new strategic orientation that will change the global balance of power. While the unipolarity shaped around the axis of American leadership has rapidly lost ground, the new position of the rising powers has led to some geopolitical consequences. The first of these was experienced when the power hierarchy changed from a vertical to a horizontal axis. It is now a matter of diffusion of power rather than a distribution of power. The emerging powers’ search for geopolitical status has both expanded and spread along the axis of economic expansion and military power fortification, and it has undermined the U.S. monopoly in different regions. Thus, there has been a change in regional power balances.15

Along with the rising powers, new sub-norms have begun to emerge under the universalist institutions of the liberal order. Emerging states have naturally tended to challenge the status quo and revise the dominant norms of the system to reflect their interests and values. Moreover, the rising powers have grown stronger on the military level in ways that are producing geopolitical results in their regions; with their deterrent and offensive character, they have ignited the developments that will allow rebellion when necessary.16 Although the U.S. has tried to prevent the emergence of these actors, including using military force, it has been unsuccessful in this regard. Thus, the rising powers’ search for new status reinforces the multilayered structure of the international system.

The New International Security Architecture

Although the new multilayered multipolarity has led to the spread/diffusion of power, it has also brought about the formation of new global and regional security architecture due to emerging global and regional geopolitical competition. Just like the new state of world politics, the global security architecture, which is an inseparable part of global politics, also presents a fragmented appearance. The security architecture of the global system during the Cold War was quite simple: No situation in which the two superpowers disagreed led to a global conflict, as every incident was calculated on the assumption of mutually assured destruction; thus, the actors preferred to use indirect fighting methods instead of overt conflict. The most distinctive feature of this architecture was the power of the states and the alliance system they created by using this power. However, the main problem of the security architecture in the new era is that the threats are extremely difficult to control.

The first characteristic feature of the new security architecture appears at the geopolitical level. The main feature of multilayered geopolitical struggle is that competition and race are not limited to states only. In classical multipolarity, the imperial geopolitical competition took place only between states and empires over economic, territorial, and military issues. The new multilayered, multipolar competition takes place between different political units as well as between states at the vertical level, while at the horizontal level it emerges in a wide range of areas, from climate to health, transportation to food, as well as economic and military issues.

The new wave of terror, initiated by the PKK with its trench warfare, presented Turkey with a new multidimensional security problem

There are four layers in the geopolitical struggle dimension of the new security architecture–and unlimited competition: space-scale geopolitics, global geopolitics, regional geopolitics, and local-scale geopolitical struggle. Although the transition between layers in the new security competition is directly related to material power parameters, the most important aspect is that local-scale security competition can create global effects.

The second characteristic feature of the new global security architecture is the changing character of war and conflict. The form, character, and extent of war constitute the distinctive features of the security architecture of the global system. Under normal circumstances, warfare is assumed to be based on three elements: force, fire, and technology. In the case of traditional war, factors such as the actors, methods, and nature of the war are important; in the new security architecture, however, the change in the number and the type of the actors involved in the conflict is significant, because the state is no longer the only actor in the war. In addition, the methods and layers of warfare have changed drastically.17 There is a multilayered battlefield in the new security architecture. The changing nature of war, from hot conflict to psychological and now hybrid warfare, has made the line between the state of war and peace more blurred and transitive in the multilayered new era. In this sense, the concept of war itself within the new security architecture has a hybrid character. For example, the war waged over Syria reflects the changing character of the war on a local, regional, and global scale in many ways.

Another feature of the new security architecture is the phenomenon of terrorism. In the context of global security, after the 9/11 attacks, while the practices of the U.S. within the framework of the preventive security doctrine diversified global security risks, they also caused a radical shift in the spatial scale of security problems. In particular, the rise and spread of ISIS have removed the borders of international security and radically changed the global security architecture.18 While terrorism deepens low-intensity conflicts in different regions, a direct correlation has emerged between efforts to ensure international security and the spread of terrorism.

The Decline of International Norms and the Rise of the Rest

Another feature of the multilayered, multipolar international system, as the influence of international norms diminishes, is the rise of non-western actors. First, the new era appears to lack a dominant global norm and a comprehensive global paradigm. The main determining principle of the American-centered liberal order was not the distribution of power; it was the international ‘constitutional’ order capable of determining the relationship between powers. While every international order reveals a global norm, these norms in turn shape the functioning of the international order. To put it more clearly, it is the existence of the norms that determine the measures by which the behavior of the political units that make up the international system will be shaped. While the U.S.-centered neo-liberal international order built such an internal functioning with the U.N. politically, Bretton Woods economically and NATO after 1945 from the security perspective, the same system transformed with the new global developments in1980s, the 1990s, and 2000s.19

Turkey introduced a new regional military strategy after 2016, increasing its cross-border military mobility and evolving into a regional player that projects power, as its involvement in Libya, Qatar, and Somalia indicates

It is possible to talk about the existence of three different political units in the context of the relationship between norms and the international order. The first of these is norm-producing political units. Although states are the producers of the norms, international institutions play a vital role in the dissemination of these norms. In some cases, states can become both producers, carriers, and implementers of the prevailing norm. The U.S. invasion of Iraq is a good example in terms of attempting to transform the international regime of external military intervention outside of the UN system. The second group consists of actors who consume the norm or comply with the norm (norm-takers). At this point, the relationship between the international order and the norm comes into play, because there is a direct relationship between adapting to the order and conforming to the norm. Actors who are not in the consumption chain of the global norm cannot be ‘normal’ players of the system, to a large extent. The third group consists of actors who oppose/defy the norm. The actors in question may be state or non-state actors. North Korea and ISIS represent good examples of this.20

The relationship between the emerging international order and the international norms is quite problematic. The first problem here is that the actors that produce international-universal norms are weak. For example, the U.S. under the Trump Administration assumed a function that undermined existing norms rather than being the producer, protector, and carrier of the global norms. What we are seeing today in the case of the U.S. is the process of strategizing the international norms rather than maintaining the universal applicability and validity of the norms. This situation largely explains the lack of common norms of the new multi-layered international order and the race of competing norms. While short-term conflict of interest is fueled in this new hybrid system, the work of alternative norm producers such as Russia and China are getting easier. This situation reveals another problem in the norm-order relationship because within the emerging international system the competition for the production and consumption of norms has diversified. In the transition period, in which a new multipolarity is emerging, the production and implementation of the global norm(s) and adherence to the norm(s) weaken(s) while alternative norm relations emerge. The continuance of this situation weakens the strategic superiority of the West and reveals the rise of the non-western world.

Turkey’s New Strategic Landscape: The Return of Power Politics and the Decline of Regional Asabiyyah21

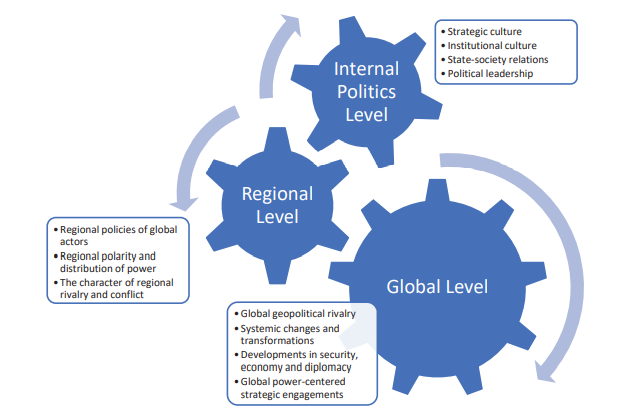

To develop Turkey’s grand strategy, first of all, it is necessary to analyze the country’s evolving strategic environment. Three levels shape Turkey’s strategic environment: national, regional, and global. There is a mutually constitutive relationship between Turkey and its strategic environment in constructing its threat perception, strategic priorities, and geopolitical position in regional and international politics; these factors must be taken into consideration in designing its grand strategy.

National Level

A historically important feature of Turkey’s strategic culture is its defensive character. While examining Turkey’s position in the international and regional system, defensive geopolitics as a discursive and practical strategy is not limited to foreign policy. The discourse and practice of defensive geopolitics have been historically constructed as an integral part of nationalism, secularism, state-centrism, and even civilizational visions that emerged in Turkey in different historical periods. More precisely, defensive strategic culture has not been only shaped the practice of foreign and security policies during the Cold War and the post-Cold War era but also constructed a particular type of political subjectivity and nation-state.”22

Although the external environment of Turkey’s strategic culture has changed to a large extent since the end of the Cold War, the 1990s were the years when the republican security culture was reproduced.23 These years, in which PKK terrorism and the Kurdish issue shaped Turkey’s security paradigm to a large extent, represent a strong return to territorial integrity as the main strategic priority. This period also went down in history as a time in which military-controlled Turkey’s political landscape as the main agency above the politics and determined its foreign and security policy.

the new regional security architecture and the security risks arising from the first level have brought about the re-emergence of the historical dynamics (such as territorial integrity) in Turkey’s strategic culture

In the ten years after the ruling Justice and Development Party (AK Party) came to power, the years in which this strategic culture was transformed, the axis of geopolitical discourse shifted significantly from the nation-state to the civilization,24 and although the military, institutionally, continued its position as a ‘securitizing actor’ in many foreign policy issues,25 it gradually had to hand over its place in the institutional struggle to the Presidency and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.26 Democratic determination of foreign and security policy became possible after the political leadership began to be effective again after a long hiatus, and after the state-society relationship was converted to an equal and mutually defining relationship from a state-supremacist one.

The Arab uprisings that started at the end of 2010 provided an opportunity for Turkey to revive and accelerate the momentum it had lost at home on the axis of regional democratic consolidation.27 However, Turkey’s foreign and security policy faced a new challenge at home, as the democratic route of the Arab Spring changed direction as a result of the military coup in Egypt and the eruption of civil war in Syria.

While fragmentation in the regional security architecture caused the emergence of new fault lines, the end of the reconciliation process, which had been weakened in July 2015 due to the PKK’s terrorist attacks, brought about the formation of a new axis of insecurity.28 ISIS’ terror attacks against Turkey, as well as FETÖ’s (Fetullahist Terrorist Organization), attempts to overthrow the government from within the country sabotaged Turkey’s internal security architecture and necessitated a refocusing of Turkish foreign and security policy on the fight against terrorism. The new wave of terror, initiated by the PKK with its trench warfare, presented Turkey with a new multidimensional security problem.

On the national, regional, and global scale, Turkey’s main strategic goal in the upcoming period should be to deepen its autonomy

Faced with the threat of the near-collapse of its internal security architecture caused by FETÖ’s coup attempt, Turkey managed to prevent the coup and worked quickly to remove the damage in its security architecture by intervening militarily in the Syrian crisis. First, it drove ISIS away from its border, then entered a new period of military activism that would make the PKK affiliated YPG’s Syria project, i.e., attempts to establish a ‘garrison state,’ largely impossible.

Regional Level: Regional Security Rivalry and the Return of Geopolitical Anxiety

In recent years, the focal point of the regional security complex, which constitutes the second level of Turkey’s strategic environment, has been developments in the Middle East. In addition to the complexity of the transformation of the Middle East after the Cold War, the Balkans, Black Sea, South Caucasus, and Mediterranean regions that makeup Turkey’s near environment have also undergone significant changes and transformations. However, none of the transformations in the Middle East radically affected Turkey’s security and foreign policy to the extent that the Arab uprisings did.29

For this reason, Turkey determined its strategy for the Arab Spring on the axis of owning this wave of change. The overthrow of authoritarian regimes, the rapid loss of power of the Assad regime in Syria, and the assumption that the international wind of change was behind the democratic dynamic of the Arab spring led Turkey to a strategy that developed as ‘leading the wave of change.’ This strategy basically aimed to shape the political developments in the region to transform the regional order.

Turkish Defense Minister Hulusi Akar and Chief of General Staff General Yaşar Güler visit the Turkish Naval Task Group’s ship in the Central Mediterranean, flying in from Mitiga Airport in Tripoli, Libya on July 4, 2020.ARİF AKDOĞAN / AA

Turkish Defense Minister Hulusi Akar and Chief of General Staff General Yaşar Güler visit the Turkish Naval Task Group’s ship in the Central Mediterranean, flying in from Mitiga Airport in Tripoli, Libya on July 4, 2020.ARİF AKDOĞAN / AA

Yet things did not go as planned. Syria was one of the first places where Turkey’s strategy to ‘lead change’ failed in 2013. Syria’s rapid transformation from a political crisis to an armed conflict, and then its evolution into a military conflict and a regional proxy war, led Turkey to adopt an offensive strategy that aims to ‘overthrow the Syrian regime’ by adopting the strategy of supporting opposition military groups not only to consolidate its foreign policy presences vis-à-vis Syrian regime but also to recalibrate its regional status. Faced with a comprehensive security crisis, including border security, with the Syrian crisis turning from an armed conflict into a new regional and global geopolitical competition, Turkey had to switch to a strategy that will enable it to ‘avoid security problems’ caused by the crisis by changing its position in the Syria-oriented Arab spring strategy.

In this period, the silence of the Obama Administration and Europe toward the bloody coup in Egypt that resulted in the overthrow and imprisonment of Mohammed Morsi30 greatly curtailed the new strategic orientation opportunity that Turkey had hoped to seize in the Arab Spring. Also, during this period, the PKK’s strategy against Turkey underwent a fundamental change; U.S. support for the PKK’s strategy of territorial expansion and autonomy in Syria deeply shook Turkey’s regional security policy. However, this period did not last long, and Turkey sought to overcome the security threats caused by ISIS and PKK with a new military engagement strategy in which military intervention became an ultimate solution. This strategy first started with Operation Euphrates Shield in 2016, continued with Operation Olive Branch in 2018, and deepened with Operation Peace Spring in 2019.

Turkey introduced a new regional military strategy after 2016, increasing its cross-border military mobility and evolving into a regional player that projects power, as its involvement in Libya, Qatar, and Somalia indicates. Before 2012, Turkey had tried to penetrate the region with its soft power by making use of the perks of being a commercial state; in 2016, it turned to a foreign and security policy that makes more extensive use of military tools. Bringing its Syria strategy to the Mediterranean via its position in Libya, Turkey cranked up its military deterrence in its contiguous region, while reinforcing its ability to take decisive diplomatic and military steps in regional crises.31

The results of Turkey’s assertive foreign policy have had important consequences for the country’s strategic orientation: first, its strategy has come to rely too heavily on military means. The conflict in Libya and Syria is one of the areas where this crystallized. The second result is the possibility of the emergence of the problem of strategic overstretch in Turkish foreign policy, as Turkey may increasingly face multidimensional challenges. The third result is the emergence of the new regional block and alliances to contain Turkey’s influence in different issues and regions.

In light of all these developments, Turkey’s regional-scale security landscape has taken on a significantly new character, one that requires a new strategic vision and roadmap for the coming period. The first distinguishing feature of this new regional security architecture is the destruction of the notion of state sovereignty. A significant number of the countries in Turkey’s regional security equation are weak and fragile states that are in conflict to a large extent, albeit at different levels. Excluding the Balkans, the fragile situation in Ukraine and the South Caucasus, Russia’s offensive policies in Syria, the situation in Nagorno-Karabakh, Iraq, Syria, and Libya are precisely the regions where the system of sovereignty has undergone serious internal and external pressure. This situation is also among the distinguishing features of the larger-scale regional security architecture in Turkey’s neighboring geography.

The second important feature of the regional security architecture is internal and external pressure on the borders.32 Non-state armed groups, which have become the most important actors of the region in tandem with the Arab Spring, have changed the border situation in Turkey’s Southern line. In areas where global-scale regional strategies and local-scale geopolitical competition are in harmony, there is stronger external pressure for the change of borders. The third characteristic feature of the regional security architecture is that the phenomenon of terrorism itself has undergone a fundamental change. The countries in which the notion of sovereignty had weakened due to the collapse of state authority quickly surrendered to terrorism, and the number of terrorist organizations increased on a regional scale. The deepening of geopolitical competition accelerated the power and security race in the regional security architecture; thus, a regional-scale change has emerged in armament dynamics. In one way or another, all state actors have been involved in an internal conflict in the Middle East, either directly or through proxies. Indeed, proxy conflict and war have become the new normal of regional security architecture and ultimately function to undermine the very nature of the ‘regional asabiyyah’ that Turkey has been trying to create since 2002.

However, the new regional security architecture and the security risks arising from the first level have brought about the re-emergence of the historical dynamics (such as territorial integrity) in Turkey’s strategic culture. While the regional-scale security environment was relatively flexible between 2002 and 2012, it provided advantages for Turkey in many ways; this new situation has changed the way Turkey’s traditional strategic culture is handled. However, the restrictive and security-driven nature of the regional security landscape after 2012 brought about the re-emergence of the historical codes such as ‘territorial anxiety’ (the fear of separation) that make up Turkey’s strategic culture.

Global Level: The Return of Power and Security Rivalry

It is not possible to say that Turkey has historically had a global-scale foreign policy agenda. However, this does not mean that Turkish foreign policy is not affected by systemic changes, nor that it does not want to influence systemic developments, nor that it does not try to adapt to global-scale systemic changes. Every state seeks ‘autonomy’ at certain scales in the international system. In this sense, the level of global politics, in which Turkey’s foreign and security policy is shaped, includes three basic elements. While the first of these is the role played by systemic changes, transformations, and ruptures in Turkey’s foreign policy, the second consists of the effects of the global-scale projection of actors’ policies toward the geography where Turkey is located. In this sense, what determines Turkey’s regional-scale foreign and security policy is the distinctive characters of the different regional security complexes of which Turkey is a part and the policies of international players toward the regional geopolitical complexes of which Turkey is a part as well. The third is the foreign and security interaction caused by Turkey’s global-scale positioning effort. There is a close relationship between these three elements.

The change process experienced on a global scale in the last twenty years has caused a new strategic dynamic in Turkey’s immediate surroundings. Turkey, which geopolitically re-positioned itself on a regional scale with the emergence of the global geopolitical fragmentation and new political geography that developed immediately following the Cold War, could not achieve the desired transformation between 1990-2002 and spent time attempting to adapt to the global systemic transformation inefficiently. In 2002, Turkey entered a new era and faced a new security crisis;33 9/11 not only had a global impact but also caused a drastic change in U.S.’ global and regional strategy. In this period, the process that started with the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan and continued with the invasion of Iraq caused a change in the balance of power in Turkey’s contiguous geography, while the Middle East region experienced an American-centered unipolar period. However, in this period, the fact that Iraq fell out of the game within the regional balance of power system in the Middle East created an opportunity for Iran to expand its sphere of influence, and the character of regional-scale competition changed significantly. More importantly, during this period the engagement policies of global actors directly interacted with regional-scale processes.

Figure 1: Turkey’s Foreign Policy and Security Equation

Source: Compiled by the authors

Although it survived the 2008 financial crisis without any major economic damage, Turkey’s European-oriented foreign policy was weakened to a large extent due to the European geopolitical fluctuations caused by the crisis and the slowdown in the EU process. Although it seems to have overcome this weakness between 2008 and 2012, new challenges appeared simultaneously: the Arab uprisings that broke out at the end of 2010 and the global, systemic challenge to Turkish foreign policy.34 While the Syrian crisis increased the burden on Turkey’s foreign and security policies on a regional scale, the ambiguous and uncertain geopolitical environment significantly limited Turkey’s mobility on a global scale.

Trying to determine and manage its foreign and security policy under the conditions of a competitive regional security climate and global uncertainty, Turkey adopted a military strategy aimed at minimizing terrorism in this period and tried to put its deteriorating bilateral relations with the U.S. back on track. One of the most important dynamics affecting Turkey’s foreign and security policy was the U.S.’ ongoing engagement in the region. The deepening of the U.S.’ passive engagement strategy toward the Middle East, which started with Obama in 2009 and increased with Trump at the helm, directly affected Turkey’s security policies in the regional security climate. Similarly, the rivalry between Russia and the U.S. in Syria led to the adjustment of Turkey’s security policies by considering this balance. With Trump’s election in 2017, the geo-economic dimension of U.S.-China rivalry came to the fore and the problems between Turkey and the U.S. deepened. Turkey attempted to overcome the contraction in its foreign and security policy with initiatives such as ‘Asia Anew,’ however, all the foreign policy issues facing Turkey necessitated its interaction with global actors in this period.

The Strategy of Autonomy

At a time when the international system is transforming, Turkey needs to approach the events taking place at the domestic, regional, and global political levels in a holistic manner to implement its grand strategy regarding foreign and security policy. The core of any grand strategy lies in politics. In other words, leaders should act by bringing together all military and non-military elements to protect and strengthen the country’s long-term interests. Strategy cannot be ‘complete or pre-given.’35 Grand strategy is as much about wartime as it is about peacetime, and it emerges with a balanced synthesis of ends and means. In other words, the goal of the strategy has to take into account not only the means by which the goal will be achieved but also the cost of achieving it. More importantly, the grand strategy should lay out a plan that “strengthens the position of the country by gaining allies, gaining the support of neutrals, and reducing the number of adversaries (or potential adversaries).”36

Turkey’s grand strategy must be comprehensive and pragmatic; it should consider the distinctive features of the transition period explained in the sections above in order to facilitate the country’s adaptation to the dynamics of the newly developing international system; it should actively implement foreign and security policies in the ‘strategic belts’ around Turkey to achieve its goals. In this context, Turkey’s grand strategy, which should be at the center of its foreign security policy, should be designed on the axis of sustainable stability and security. On the national, regional, and global scale, Turkey’s main strategic goal in the upcoming period should be to deepen its autonomy. Such autonomy can only be possible if Turkey diversifies and develops its opportunities.

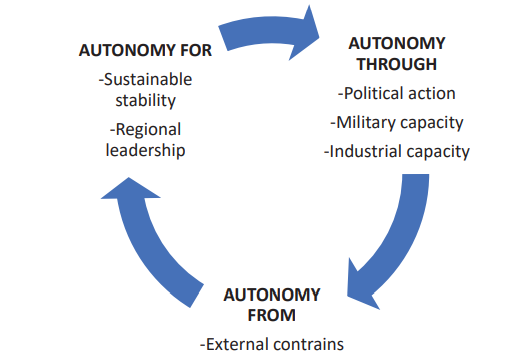

For Turkey to have a ‘strong strategic autonomy’ at the domestic and regional levels mentioned above, it should first act in a way that maintains its political (diplomatic), economic, military, and industrial autonomy, and then spread the gains it has achieved

Strategic autonomy is the free and independent exercise of political action. In this sense, autonomy has three generally accepted components: (i) political autonomy –the ability to make decisions in the field of foreign, security, and defense policies; (ii) military autonomy –the ability to independently plan and execute military operations; and (iii) industrial/technological autonomy –the industrial capacity to produce the materials necessary for conducting both civil and military operations and to maintain the country’s infrastructure for everyday operational autonomy.37 Strategic autonomy should be seen as a point along a spectrum that reflects positive and negative dependencies in a country’s foreign, security, and defense policies.38 In the case of Turkey, it is possible to define autonomy as the potential and ability to implement the country’s political and military objectives via bilateral relations or through an alliance (if there is one), or totally on its own if there is no alliance, by centralizing its national, regional, and international strategic priorities.

The capability of having power affects a country’s level of autonomy. Capability may refer to a country’s material and non-material capacity. Another element of strategic autonomy should be understood as the resources a country possesses; these resources at least partially determine what goals are possible, i.e., how much of a certain resource is required to meet a certain goal. The third element is freedom of movement (mobility). The fourth element of autonomy is flexibility, which can be defined as the ability to change or adapt to change in a short time with little cost and effort.

The elements on which strategic autonomy is based enable the effective use (operationalization) of the skills that must be possessed. In this sense, first of all, the ability to know and predict the future constitutes one of the most important principles of autonomy. This ability must be supported by the freedom to make decisions. The ability to make free decisions is the central feature of strategic autonomy. The third principle of strategic autonomy is the freedom to act (strategically). Capabilities, which are an integral part of strategic autonomy, must first provide, protect, and expand areas of autonomy. In other words, for Turkey to have a ‘strong strategic autonomy’ at the domestic and regional levels mentioned above, it should first act in a way that maintains its political (diplomatic), economic, military, and industrial autonomy, and then spread the gains it has achieved.

The odds are against absolute strategic autonomy. However, there can be strong and durable strategic autonomy. Strong autonomy is also the key to sustainable stability, which is described as part of Turkey’s grand strategy. This kind of autonomy means that a country is largely self-sufficient at the economic, military, and technological levels and that it plays an effective deterrent role in the field of security and foreign policy in its close regions.

For Turkey to achieve comprehensive and absolute stability at home, and to achieve its regional leadership by targeting relative sustainable stability in its region, it is imperative that it gains the ability and opportunity to act autonomously. Such an opportunity will enable Turkey to produce a preventive and active policy and to manage power projections policy within the scope of competition on a regional scale with its neighbors. More importantly, it will have the ability to act on its own when necessary to protect its primary interests, and the options for strategic decision-making and action will multiply. Ultimately, achieving a ‘strong strategic autonomy’ will bring Turkey to play a more active role in the regional-scale geopolitical environment to position itself as a ‘leader country’ in the region. Accordingly, the objective of Turkey’s grand strategy should be designed to prevent other countries from taking either a dominant position or attaining strategic superiority over regional issues that could undermine Turkey’s regional power status.

Figure 2: Turkey’s Strategy of Autonomy

Source: Compiled by the authors

Adjustment of Turkey’s Grand Strategy

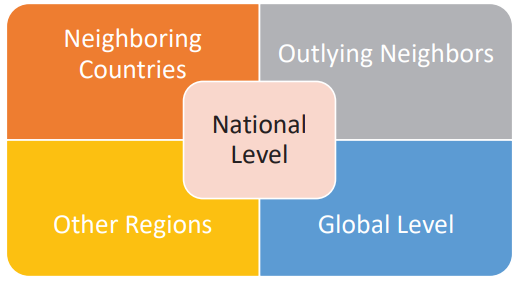

The areas that Turkey should prioritize in its foreign and security policy are multilayered and diverse. Categorizing these layers offers a reasonable and broad perspective to implement Turkey’s grand strategy. Although not subject to any hierarchy, it is possible to consider Turkey’s ‘strategic layers’ at five levels, from national to global, in terms of foreign and security policy. These belts are not propositions of any priority in terms of Turkey’s foreign and security policy; they are an alternative framework to make sense of our proposed grand strategy.

It should be underlined that the first belt, which represents the national level, is vital for a healthy engagement with the agendas of the other belts. However, this importance does not indicate that other levels or regional and global developments should be ignored. On the contrary, within the framework of Turkey’s new strategic orientation, it is essential that Turkish policies and the general agenda in each one of the layers be carried out simultaneously with a holistic approach. Moreover, each layer interacts with its own elements and with other layers and intertwining between layers in some specific areas is particularly evident.

Absolute stability at the national level has a dynamic structure; it should constantly be reviewed in light of existing and emerging risks, and it should be constantly maintained

In this context, although the national level is the most important area for Turkey to achieve its strategic objective, it cannot be considered independently of the second belt, which includes Turkey’s border neighbors. Similarly, the zone in which the border neighbors are located cannot be considered independently from Turkey’s primary interests in the context of the goal of sustainable stability in the regional area where other actors and problems are located. On the other hand, while the strategic alternatives within the national and regional levels are a necessity in terms of the choices that Turkey will make in its strategic orientation, the regional and international strategic layers that contain more global-scale elements consist of preferences rather than necessities. For this reason, there is a gradual relationship and transition between strategic belts.

Figure 3: Strategic Layers of Turkey’s New Geopolitics

Source: Compiled by the authors

National Level

The national level has the potential to affect Turkey’s engagement with other layers in terms of slowing down/accelerating it. In this respect, when strategic belts are considered as layers, the first strategic layers should be positioned as the core. As a matter of fact, failure in this strategic zone has the potential to doom all initiatives in other strategic belts.

The area where Turkey’s grand strategy of ‘sustainable stability’ starts is the national level. The quality of sustainable stability at the national level has to be comprehensive and absolute. In other words, absolute and comprehensive stability at the national level is not a condition for Turkey’s grand strategy: it is an essential part of Turkey’s strategic priorities particularly in repositioning itself under the changing international system. For this reason, Turkey should first create the infrastructure of its absolute stability in this zone, then create sustainable and effective mechanisms to remove the disruptive elements that would harm this stability, and finally, develop and deepen this absolute stability. Absolute stability at the national level has a dynamic structure; it should constantly be reviewed in light of existing and emerging risks, and it should be constantly maintained.

It is possible to identify the risk factors at the forefront in the first strategic zone in the short and medium-term as terrorism, economic crisis, deepening social polarization, and refugee remobilization and flux.

Neighboring Countries

The second strategic zone, which includes the areas adjacent to Turkey, includes the countries that share a land border with Turkey as well as the maritime areas and connected geography that have come to the fore with the conceptualization of ‘Blue Homeland’ in recent years. The developments in the countries in the second zone have the potential to directly affect Turkey’s security as a whole and arguably constitute the center of gravity of international politics. In this respect, it would not be wrong to describe the second belt as Turkey’s last protective shell before the core/center. If this shell is broken or thinned, it will not be possible for Turkey to establish comprehensive stability at the national level. However, since the countries in this layer do not have the same impact on Turkey’s foreign and security policy, they should be considered in two different groups and a different engagement should be developed for each.

MENA, which has topped the agenda of Turkish foreign and security policy in the last decade, will continue to be one of the main items on Turkey’s roadmap in the new period

The first group includes Syria, Iraq, Iran, Greece, and the three maritime areas, which together continue to be at the center of Turkey’s domestic and regional security policy in the short and medium-term. The second group consists of Georgia, Bulgaria, and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC); these neighbors are relatively more stable in the short and medium-term compared to the first group, and rapid changes are not expected there.

It should be noted that this layer is the main source that influences Turkey’s stability at the national level and also the source of challenges against the security and foreign policies of the country. Addressing the challenges posed by the countries of this region will directly contribute to Turkey’s stability.

Turkey’s policy toward the second layer should be relative, not absolute stability. Although Turkey is an important actor in directing the many developments taking place in all the countries of this layer, its options and capabilities may be insufficient to direct these developments alone. For this reason, establishing and maintaining stability that is not as absolute as at the national level but relatively sustainable, should be Turkey’s priority in this generation.

In this context, relative stability does not mean stability at all costs. Rather, relative stability is stability that is sustainable and prone to minimal compromise. In regard to the countries of this region, relative stability refers to the creation of minimum levels of democracy, representation or legitimacy, the elimination of conflictual elements, and the preservation of stability after it is established; in terms of the three maritime areas, relative stability means the adoption of the situation accepted by Turkey and on which consensus has been achieved or is likely to be achieved by the parties.

Developments in the pre-pandemic period make it difficult to establish and maintain relative stability in some countries in this strategic belt; the most prominent characteristic of the region –which includes Syria, Iraq, and Iran– is that it is susceptible to very rapid developments. Regional dynamics can constantly change based on countries and even within countries themselves. In this respect, in line with the diversified geopolitical portfolio, the second layers are perhaps the area where the principle of strategic flexibility is most essential.

Outlying Neighbors

We define the third strategic layer as ‘outlying neighbors.’ This layer covers the regions in which Turkey is located or the areas where developments occurring in them more directly affect Turkey’s grand strategy. These are non-contiguous regions that affect Turkey’s interests, such as the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), Europe, the Balkans, and Central Asia.

Turkey’s aim in this strategic zone is relative, sustainable stability. However, in achieving this goal, Turkey is subject to certain restrictions on directly shaping the developments occurring in the regions of this layer, since each of the regions, which has a multidimensional portfolio in terms of geopolitics, has its own characteristics. When this situation is considered together with the involvement of both intra-regional dynamics and extra-regional forces in the processes, it creates limitations not only for Turkey but also for all actors.

It seems very likely that Turkey’s geopolitical environment will undergo extensive transformations and ruptures in the next ten years

To the extent that Turkey achieves its strategic autonomy target in line with its main objective of sustainable stability in the third layer, it will also be able to test the limitations created by regional dynamics. In other words, the deeper Turkey’s strategic autonomy, the more it will test and push the limits in the regions in this layer and increase its ability to shape regional trends/developments. Therefore, with the strengthening of its strategic autonomy, Turkey’s medium-term position in this layer will transform from being a reactionary to being an actionist in many cases, and its ability to take initiative and determine regional trends/developments will increase.

The importance of the third strategic layer in Turkey’s grand strategy is its direct relationship with the second layer and thus with the national layer. The whole of the second layer, which is the last protective shell of Turkey before the core, constitutes a subsystem of the regions in the third layer. When each region in the third strategic layer is considered as a regional system, the emerging trends in the regions inevitably affect the countries and the main core in the second strategic layer.

Therefore, each of the regions of MENA, Europe, the Balkans, and Central Asia has an irreplaceable place in terms of Turkey’s grand strategy. In the new period, there will be no hierarchy in the approach to these regions, and that all capabilities and tools be mobilized comprehensively in line with the strategic autonomy goal. This does not mean that the level of response to a trend or risk in any region is the same in all regions. Indeed, in the pre-pandemic period, some of these regions were more prominent in terms of Turkey’s strategic interests and included serious challenges to its stability in the second and first strategic layers. In the new period, there will be a similar situation in the regional context. However, priority or urgency in one region should not result in the neglect of other regions. In other words, although there is no hierarchical order, urgent situations/regions should be prioritized, but this should not narrow Turkey’s vision in the third strategic layer.

MENA, which has topped the agenda of Turkish foreign and security policy in the last decade, will continue to be one of the main items on Turkey’s roadmap in the new period. In this region, where the greatest instability prevails, the relative elimination of disruptive elements as Turkey’s strategic autonomy increases will play an important catalyst role for the implementation of the grand strategy. The Middle East has been undergoing rapid changes recently and the balance of power has been changing at short intervals. The dynamics of these developments affect alliances and collaborations, and regional events are becoming more and more fragmented rather than integrated.

Other Regions

The fourth strategic layer covers a wider area and includes regions such as the Horn of Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and Asia. This layer has been developed in line with Turkey’s sustainable stability grand strategy without geographical, historical, or cultural limitations. Although Turkey’s main objective in this strategic zone is expressed as relative stability in accordance with the grand strategy, the role that Turkey will play in ensuring relative stability may vary from region to region. In other words, while Turkey has the potential to contribute more actively to achieving and maintaining relative stability in some parts of this strategic layer, it has a more limited role in achieving relative stability in other regions and should therefore aim at promoting rather than creating relative stability. In this context, the Horn of Africa and partially Sub-Saharan Africa can be included in the first group, while Latin America and Asia can be largely placed in the second.

The reason why the Horn of Africa, which includes Somalia, Eritrea, and Djibouti, is in the first group is due to the positive contribution that Turkey’s activities have made in the last ten years to the stability of this region. While many of Turkey’s activities in the region have taken place in Somalia, the deepening of Turkey’s diplomatic, economic, and development aid/humanitarian aid and relations to be developed with Eritrea and Djibouti as well as Somalia in the new period will play an important role in minimizing the elements of disruption in the region and in establishing relative stability.

Turkey does not have the luxury of waiting for the risks in each strategic layer to turn into threats, or of reacting too late/insufficiently to problems that could snowball into bigger issues

Sub-Saharan Africa covers wide geography in terms of geopolitics. Excluding five countries in North Africa and three in the Horn of Africa, there are 46 countries in the region. Considering the breadth of this geography, the multiplicity of the actors involved and the instability in the region, Turkey’s capacity to contribute relative stability in this region is of course not as likely as it is in the Horn of Africa. For this reason, the goal of ‘promoting’ relative stability in this region should be at the forefront rather than the goal of ‘providing’ relative stability. Turkey has an important advantage in the region, as it does not have any colonial past there and has no neo-colonial ambitions and intentions in the relations it will establish in the new period.

Compared to other regions, Latin America is geographically the farthest region from Turkey and the newest in terms of relations, which dates back only to the most recent period. Turkey’s fundamental position in this region in the new period should be encouraging rather than stabilizing. A humanitarian aid policy in tandem economic and diplomatic dimensions will be more prominent in Turkey’s unfolding engagement with the region.

Asia, on the other hand, covers geographies that are largely defined as Asia-Pacific and Far-East in terms of geopolitical imagination. In this context, it is important in itself that Turkey started the ‘Asia Anew’ initiative in the pre-pandemic period within the framework of its attempt to diversify its foreign policy scale and broaden its vision. In terms of content, the ‘Asia Anew’ initiative is an important initiative that can be adapted to all regions in this strategic belt, which Turkey anticipates will be prominent in the new period.

Global Level

The last dimension in Turkey’s grand strategy is global. It includes international organizations, especially the UN, and the leading actors of the global system. In this strategic layer, as in the fourth strategic layer, Turkey’s fundamental position should be to promote relative stability rather than to create relative stability. For Turkey, unlike the fourth strategic layer, the 5th strategic zone has two features: normative and functional.

Turkey’s primary field of activity in this layer consists of attempts to revive the norms that exist at the global level but have lost their functionality, and efforts to determine new norms/principles to address current developments. In this context, Turkey’s vocalization of criticisms about the weaknesses of the global system in the pre-pandemic period may be seen as an advantage. For example, the normative dimension of the gripe of the global system, which was discussed above, was clearly expressed by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan with the motto ‘The World Is Bigger than Five’ and his book A Fairer World Is Possible.

Criticisms against the system in the pre-pandemic period remain valid regarding global issues such as injustice, poverty, responsibility to protect, xenophobia, Islamophobic movements, and the refugee problem. These problems and the criticisms they raise will continue to dominate the global agenda and are likely to become even more diversified and far-reaching in the new period. At this point, Turkey’s rhetoric must be supported by engaging with the countries, particularly in the third and fourth layers, in the new period. Turkey also supports initiatives that propose global solutions for global problems. In this sense, Turkey needs to declare its perspective and offer its solutions to other global issues, especially UN reform, by forming a working group.

Conclusion

It seems very likely that Turkey’s geopolitical environment will undergo extensive transformations and ruptures in the next ten years. If Turkey chooses to adopt a flexible foreign policy strategy, it can avoid the effects of the problems that may arise during the transition period. Flexibility is a foreign policy strategy that will increase Turkey’s options, expand its room for maneuver and reduce the costs of its regional leadership role.

In this article, we have identified five strategic layers covering national, regional, and global levels to provide an analytical framework and to assist Turkey in preparing for and navigating this transition period. Although these strategic layers are interrelated, the national level constitutes the main core as the locomotive of Turkey’s foreign and security policy. Every precaution should be taken against the risk and instability elements in each of the strategic zones to prevent the emergence of larger threats. Turkey does not have the luxury of waiting for the risks in each strategic layer to turn into threats, or of reacting too late/insufficiently to problems that could snowball into bigger issues. Increasing strategic autonomy is one of Turkey’s most important options. Turkey has the opportunity to envision, develop, and steer its own transformation simultaneously with the transformation process occurring in the global system, and the potential to consolidate its power status in a competitive geopolitical landscape in its region.

Endnotes

1. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, “Türkiye’nin Salgının Önlenmesinde Örnek Alınan Bir Konuma Gelmesi Hepimizin Ortak Başarısıdır,” Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Cumhurbaşkanlığı, (May 28, 2020), retrieved September 4, 2021, from https://www.tccb.gov.tr/haberler/410/120316/-turkiye-nin-salginin-onlenmesinde-ornek-alinan-bir-konuma-gelmesi-hepimizin-ortak-basarisidir-.

2. Øystein Tunsjø, The Return of Bipolarity in World Politics China, the United States, and Geostructural Realism, (Columbia University Press, 2018); Clifford Kupchan, “The New Bipolarity: Reason for Cautious Optimism,” Valdai Club, (October 21, 2021), retrieved from https://valdaiclub.com/a/highlights/the-new-bipolarity-reason-for-cautious-optimism.

3. Muhittin Ataman, “Coronavirus and International Organizations,” SETA, (April 22, 2020), retrieved from https://www.setav.org/en/coronavirus-and-international-organizations/.

4. Barış Özdal, Is the EU a Political Dwarf, a Military Worm? (Bursa: Dora, 2013); Filiz Cicioğlu, “Can the EU Leave the Confidence Crisis behind?” Kriter, Vol. 5, No. 46 (May 2020).

5. Mehmet Halil Mustafa Bektaş, “Examining the Possibility of an Eastphalian International Order,” İstanbul University Faculty of Political Science Magazine, Vol. 26, No. 2 (2017), pp. 111-130.

6. Amitav Acharya “After Liberal Hegemony: The Advent of a Multiplex World Order,” Ethics and International Affairs, Vol. 31, No. 3 (2017), pp. 271-285.

7. John Levis Gaddis, Strategy of Containment: A Critical Appraisal of American National Security Policy During the Cold War, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

8. Tayyar Arı, International Relations and Foreign Policy, (İstanbul: Alfa, 2017), pp. 156-178.

9. Arı, International Relations and Foreign Policy, pp. 156-178.

10. Nuno Monteiro, Theory of Unipolar Politics, (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

11. Acharya, “After Liberal Hegemony,” pp. 271-285.

12. Muzaffer Ercan Yılmaz, “The Rise of Ethnic Nationalism, Intra-State Conflicts and Conflict Resolution,” TESAM Akademi, Vol. 5, No. 1 (2018), pp. 11-33.

13. Acharya, “After Liberal Hegemony,” pp. 271-285.

14. “MİKTA,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Turkey, retrieved April 10, 2020, from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/mikta-meksika_-endonezya_-kore_-avustralya_.tr.mfa.

15. Ziya Öniş and Mustafa Kutlay, “Rising Powers in a Changing Global Order: The Political Economy of Turkey in the Age of BRICs,” Third World Quarterly, Vol. 34. No. 8 (2013), pp. 1409-1426.

16. Matthew Stephen, “States, Norms, and Power: Emerging Powers and Global Order,” Millennium: Journal of International Studies, Vol. 42, No. 3 (2014), pp. 888-896.

17. Yücel Özel Ertan and İnal Tekin (eds.), Changing Model of War: Hybrid Warfare, translated by Melih Arda Yazıcı, (İstanbul: National Defense University, 2018).

18. Ufuk Ulutaş, The State of Savagery: ISIS in Syria, (Ankara: SETA, 2017).

19. John Ikenberry, Liberal Leviathan: The Origins, Crisis, and Transformation of the American World Order, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012).

20. Murat Yeşiltaş and Tuncay Kardaş (eds.), Non-state Armed Actors in the Middle East: Ideology, Geopolitics and Strategy, (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2018).

21. Asabiyyah is used as the main concept by Ibn Haldun to define group solidarity, natural solidarity, social solidarity, and group feeling. It is also defined as ‘constitutive principles.’ See, Engin Sune, “Non-Western International Relations Theory and Ibn Haldun,” All Azimuth, Vol. 5, No. 1 (January 2016), p. 81.

22. Murat Yeşiltaş, Geopolitical Mindset and Military in Turkey, (İstanbul: Kadim Yayınları, 2016); Ali Balcı, Settling Accounts in Foreign Policy: AK Party, Military, and Kemalism, (İstanbul: Etkileşim Yayınları, 2015).

23. For the general framework of foreign policy during late President Turgut Özal’s tenure, please refer to: Muhittin Ataman, “Leadership Change: Özal Leadership and Restruction in Turkish Foreign Policy,” Alternatives: Turkish Journal of International Relations, Vol. 31 (2008); Muhittin Ataman, “Özal Leadership and Restructuring of Turkish Ethnic Policy in the 1980s,” Middle East Policy, Vol. 38, No. 4 (2002).

24. Burhanettin Duran, “Understanding AK Party’s Identity Politics: A Civilizational Discourse and Its Limitation,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 15, No. 1 (2013); Ali Balcı and Nebi Miş, “Turkey’s Role in the Alliance of Civilizations: A New Perspective in Turkish Foreign Policy,” Turkish Studies, Vol. 9, No. 3 (2008).

25. Tuncay Kardaş and Ali Balcı, “The Changing Dynamics of Turkey’s Relations with Israel: An Analysis of Securitization,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 14, No. 2 (2012), retrieved from https://www.insightturkey.com/articles/the-changing-dynamics-of-turkeys-relations-with-israel-an-analysis-of-securitization.

26. Nebi Miş, Turkey’s Presedential System: Models and Practices, (Ankara: SETA, 2018).

27. Hasan Yükselen, Strategy and Strategic Discourse in Turkish Foreign Policy, (Pagrave McMillan, 2019).

28. Murat Yeşiltaş and Necdet Özçelik, When Strategy Collapses: The Failure of the PKK’s Urban Terrorist Campaign, (Ankara: SETA Publishing, 2018).

29. Kılıç Kanat and Kadir Üstün, “US-Turkey Realignment in Syria,” Middle East Policy, Vol. 22, No. 4 (2015).

30. İsmail Numan Telci, Egypt: Revolution and Counter-Revolution, (İstanbul: SETA, 2017).

31. Murat Yeşiltaş, “Deciphering Turkey’s Military and Defense Strategy,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 22, No. 3 (2020), retrieved from https://www.insightturkey.com/articles/deciphering-turkeys-assertive-military-and-defense-strategy-objectives-pillars-and-implications.

32. Şaban Kardaş, “The Transformation of the Regional Order and Non-state Armed Actors: Pathways to Empowerment,” Yeşiltaş and Kardaş (eds.), Non-state Armed Actors in the Middle East.

33. Kemal İnat and Buhanettin Duran, “AK Party’s Foreign Policy: Theory and Application,” Demokrasi Platformu, Vol. 1, (2006), pp. 1-39.

34. Kılıç Buğra Kanat, The Tale of Four August: Obama’s Syria Policy, (Ankara: SETA Publishing, 2018).

35. Paul Kennedy, Grand Strategies in War and Peace, translated by Ahmet Fethi, (İstanbul: Totem Yayınları, 2014), pp. 14-15.

36. Kennedy, Grand Strategies in War and Peace, pp. 14-15.

37. Ronja Kempin-Barbara Kunz, “France, Germany, and the Quest for European Strategic Autonomy: Franco-German Defence Cooperation in a New Era,” SWP-IFRI, (2017).

38. Şaban Kardaş, “Quest for Strategic Autonomy Continues, or How to Make Sense of Turkey’s ‘New Wave,’” GMF on Turkey, (2011).