Introduction and the Argument

The failed coup attempt of 15 July 2016 in Turkey, poses a conceptual puzzle for political scientists and historians of democracy. When the Turkish people’s massive civilian mobilization and resistance defeated the coup, very different explanatory frames and narratives began to compete in order to make sense of what had happened and why, both in the media and among the scholarly community. In this article, I argue that Turkey went through a civil rights movement, or a “silent revolution,”1 under the AK Party governments between 2002 and 2013, in which the legally sanctioned segregationist measures and categorical inequalities that had structured the country’s political and social order since the founding of the Republic were gradually abolished. Most importantly, this silent revolution allowed for the public expression of religious observance and ethno-linguistic distinctiveness, thus elevating the status of previously denigrated religious conservatives and ethno-linguistic minorities to the level of equal citizenship. Removal of the headscarf ban in education, public service, and elected office, which affected roughly sixty percent of Turkish women,2 and the beginning of publicly-funded broadcasting and education in Kurdish, Zaza, and other minority languages, are the most spectacular examples of this egalitarian movement. The political capital that the AK Party accumulated as a result of these reforms cannot be overstated. Religious conservatives and ethno-linguistic minorities, which together make up a large majority of the electorate, were emancipated from their positions as second-class citizens. The moral high ground that the AK Party gained as a result of these emancipatory reforms helps to explain its successive victories in eleven national electoral contests, including local, national, and presidential elections and referenda, indicating a level of popularity which is unprecedented in Turkish political history.

Turkey went through a civil rights movement, or a “silent revolution,” under the AK Party governments between 2002 and 2013, in which the legally sanctioned segregationist measures and categorical inequalities that had structured the country’s political and social order since the founding of the Republic were gradually abolished

The AK Party’s radical reforms initially elicited a visceral, negative reaction from some secularists and nationalists, but the necessities of electoral competition led to a gradual democratic coevolution of the main political parties, evidenced in the sporadic cooperation between AK Party, the MHP, the CHP, and the HDP on some key issues over the years. However, these reforms posed a far more existential challenge to two clandestine and illegal organizations that use violent means to terrorize society – namely, the Kurdish socialist PKK and the messianic religious cult of Fetullah Gülen.3 The AK Party’s reforms, which allowed for public expressions of religious observance and ethno-linguistic expression deprived the Gülenists and the PKK of their raison d’être, respectively. The all-out offensive that the PKK launched against Turkey in July 2015, and the Gülenist attempt at a military coup in July 2016 can be interpreted as the most violent reactions4 to-date against the non-violent civil rights movement Turkey has been engaged in under the AK Party governments.

The Primary Contradiction of Turkish Politics: Secularist5 Segregation and the Exclusion of Ethno-Religious Expression

Most political communities are founded upon and defined by one or more key contradictions. For example, Anthony Marx analyzed Brazil, South Africa, and the United States on the basis of “race,” explaining why and how the white elites’ conflict and cooperation over the exclusion of blacks after slavery defined politics in South Africa under apartheid and segregationist southern states in the United States, and comparing these scenarios to the different dynamics underpinning the lack of segregation after emancipation in Brazil.6 Michelle Alexander discussed American history in terms of three periods, corresponding to the slavery (until 1865), segregation (until the 1960s), and incarceration (present-day) of African-Americans citizens.7 As such, the segregation and subordination of African-Americans, and the struggles to manage, soften, or overcome the racial fault line, indicate the primary contradiction of politics in the United States.

What has been the primary and defining contradiction of politics in modern Turkey? I previously argued that Turkey was “founded on the basis of an Islamic mobilization against non-Muslim opponents” during the “National8 Struggle” (Milli Mücadele, 1919-1922), “but having successfully defeated these non-Muslim opponents, [the] political elites chose a secular and monolingual nation-state model,” which “led to recurrent challenges of increasing magnitude to the state in the form of Islamist and ethnic separatist movements,” providing the primary contradiction of Turkish politics.9 What role, if any, Muslim identity and Islam as a religion should play in the public sphere and political order of the Republic is the primary question facing modern Turkey. I consider Algeria and Pakistan,10 the latter as “the Muslim state,” and also Israel, “the Jewish State,” to be struggling with a similar challenge,11 to which each country has devised its own particular “solution.”

Turkey’s approach to religious identity and religiosity in the public sphere was modeled on the French Third Republic; arguably, however, Turkey went beyond the French prototype in excluding and even criminalizing the religious observances and symbols of the majority religion, Islam, from official platforms including the legislature, the executive branch, the military, the judiciary, and the bureaucracy. (On the other hand, Turkey was certainly not Albania, where the Communist state went on an offensive to eradicate religion throughout society.) Thus, a bifurcated political and social structure emerged in Turkey with de facto segregation between religious and secular sectors, where the majority – the more religious conservative populations – remained and even thrived in the “periphery,” but the political, economic, and bureaucratic “center” was the preserve of the secular sector.12 Upwardly mobile people from the religious conservative periphery regularly migrated, literally and figuratively, to the secular center, but in this process they either genuinely abandoned or carefully concealed any behavior that might be indicative of religiosity. In short, secularist representatives (elected) and bureaucrats (appointed), including, most importantly, the military elite and the judiciary, governed a country that remained significantly religious-conservative by most international standards.

There are many symbolic and substantive indicators of the exclusion of religious conservatives from the peaks of political, military, and judicial power. Roughly half of Turkish men attend weekly Friday prayers, and more than sixty percent of Turkish women wear some kind of headscarf.13 In stark contrast to this “conspicuously” religious demography, after Turkey adopted a secular form of government in the 1920s, none of the first seven presidents were known to attend the weekly Friday prayers, which can only be performed collectively in public, and cannot be performed individually.14 This did not prevent secularist news outlets to speculate, for example, that Ismet Inönü was deeply but secretly religious,15 which supports my argument that one could only be “secretly” religious in the high echelons of elected office, be it military, judiciary, or bureaucratic. Similarly, as late as 1982, bureaucrats reportedly prevented military coup leader and seventh president Kenan Evren from participating in the Friday prayers that preceded his wife’s funeral.16 After more than six decades, the eighth president Turgut Özal (1987-1993) was the first one known to attend Friday prayers, and known to be religiously observant in general.

A similar but much better known and politically controversial situation prevailed with the status of First Ladies. None of the spouses of the first ten presidents, including Özal’s, wore a headscarf. In fact, once the AK Party came to power in 2002, the tenth president and ardent secularist Ahmet Necdet Sezer (2000-2007) purposefully chose not to invite the spouses of the members of the AK Party government to official receptions, in order to prevent women wearing headscarves from entering the Presidential Palace and other public spaces of political significance. Eleventh president Abdullah Gül’s tenure (2007-2014) was the first time in more than eight decades that Turkey had a First Lady wearing a headscarf.

The Kurdish question can be defined as a secondary problem that is a derivative of the primary problem of Turkey’s secularist-religious fault line

Not only were beards for men and headscarves for women strictly forbidden in the military; even female relatives of military personnel wearing headscarves could not participate in social gatherings such as weddings and graduations in the military zones. Six of the first seven presidents, who presided for 54 of the first 64 years of the Republic, were former military officers.17 The only civilian president during this long period was the one overthrown by a military coup, persecuted in a show trial, and dealt a death sentence, which was converted to a prison sentence due to his advanced age.18

The headscarf has both symbolic and substantive significance, as it has prevented more than half of all Turkish women from access to education, public service, and even elected office, as the case of Merve Kavakçı demonstrated in 1999.19 To a lesser degree, a similar situation was the case for some religiously observant men whose beards and attire prevented them from public service and education due to the official, secular dress codes. Since far fewer men disobey or deviate from the secularist dress codes than women in Turkey, such discrimination did not attract as much attention. In short, the laws and regulations against many forms of religious observance, including religiously inspired dress codes, had the effect of creating a nationwide segregation between religious and secular lifestyles at all levels of the state apparatus, and in the “public sphere” (kamusal alan) permeated by state functionaries, including university personnel, reaching a political fever pitch as one ascended to the peaks of the executive branch, the legislature, the military, the judiciary, and the bureaucracy.

The Kurdish Question as a Derivative of the Secularist-Religious Fault Line

Most scholars, including experts and specialists on ethnic identity politics, often fail to appreciate, or overlook, the direct connection between the secularist-religious fault line in Turkish politics and the Kurdish question. Moreover, some even go as far as to identify the Kurdish question as Turkey’s primary problem. On the contrary, I argue that the Kurdish question can be defined as a secondary problem that is a derivative of the primary problem of Turkey’s secularist-religious fault line. As Senem Aslan demonstrated in her comparison of Berber and Kurdish dissent in Morocco and Turkey, respectively, the primary reason behind the Kurdish question has been the high level of state intrusion and the Kemalist social engineering project in Turkey that aimed to change the ordinary citizens’ way of life, including their customs, dress codes, and gender relations.20 Moreover, the Kurdish way of life under attack by the social engineering project of the state, correctly or incorrectly, was perceived as part of the Islamic tradition. Thus, it was not Kurdish ethnicity per se, but the Kurds’ traditional way of life, which was strongly influenced by religious mores, that was seen as a threat to be eradicated. Zafer Toprak, the founding director of the Atatürk Institute at Boğaziçi University, explicitly argued that, “Atatürk had a religion problem, not a Kurdish problem.”21

Why and how the AK Party amassed such unprecedented popular support cannot be explained without reference to the historic reforms that the party implemented, which emancipated religious conservatives and ethnic Kurdish citizens from second-class citizen status

The Kurds identify themselves, and are perceived by others, as a particularly religious Islamic ethnic group.22 Many Islamic religious orders (tarikats) in Turkey have been identified as having had Kurdish spiritual leadership in the past or even at present.23Moreover, Kurds have been identified as the “backbone” of the political Islamist movement in Turkey.24 As Ümit Cizre25 and Burhanettin Duran26 have argued, Islamist intellectuals and politicians affiliated with the Welfare Party, the predecessor of the AK Party, were very open to reforming the nation-state in Turkey in order to accommodate the ethnic, cultural, and linguistic demands of the Kurdish minority. Despite the critical role of Islamic and Islamist thinking on the Kurdish question, Islamic perspectives on ethnicity, nationalism, and especially Muslim ethnic minorities in Muslim-majority societies are significantly understudied as Muhittin Ataman has emphasized.27 Against this political historical background of the exclusion of Islamic and ethnic expression, the AK Party was founded in August 2001 and swiftly came to power in a landslide election victory in November 2002, which was soon followed by reforms that led to the elevation of religious conservatives and ethnic minorities from second-class citizenship to symbolic equality, which I discuss in the next section.

A “Silent Revolution”: the End of Segregation for Turkey’s Religious Conservative Citizens

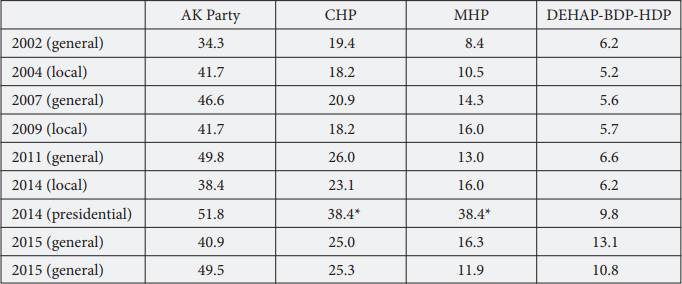

The AK Party was founded in August 2001 and came to power in the general elections of November 2002 with a landslide, receiving 34 percent of the popular vote. More significantly, the AK Party would increase its vote share to approximately 50 percent over the following years, and went on to win four more general elections in 2007, 2011, and twice in 2015, as well as the local elections in 2004, 2009, and 2014, and the presidential election in 2014 (Table 1).

Table 1: Electoral Hegemony of AK Party (percentage of the national vote), 2002-2015

The AK Party’s electoral record of uninterrupted victories over nine national elections is unprecedented. Equally significant, Turkey’s second largest party, the CHP, usually received only about half as many votes as the AK Party. Finally, and most significantly, the AK Party’s voter base is far more dispersed across all the provinces and regions of Turkey, unlike the CHP, the MHP, and the BDP-HDP, which are concentrated in particular regions. For example, in the 2011 general elections, the AK Party surpassed 10 percent in all 81 provinces, including more than a dozen Kurdish-majority provinces. In contrast, the CHP failed to garner 10 percent of the vote in 15 provinces, and the MHP failed to garner 10 percent of the vote in 22 provinces. Finally, the Kurdish socialist BDP-affiliated independents failed to garner 10 percent of the vote in 66 provinces. In short, the AK Party has built and maintained an electoral hegemony in Turkish politics, at least since 2007. Why and how the AK Party amassed such unprecedented popular support cannot be explained without reference to the historic reforms that the party implemented, which emancipated religious conservatives28 and ethnic Kurdish citizens from second-class citizen status. Non-Muslims, who are electorally marginal (approximately 0.2 percent), and who were also treated as second-class citizens as I have discussed at length elsewhere,29 also benefitted from the AK Party’s historic reforms in the laws regarding non-Muslim foundations – reforms which facilitated the restitution of some non-Muslim properties seized by the state decades ago.30

Both demographically and symbolically, the most consequential and significant reforms that the AK Party undertook were the removal of discriminatory and segregationist measures against religious conservatives, especially women wearing headscarves. In 2007, the vehement criticism of the opposition against the AK Party’s candidate for presidency, Abdullah Gül, was in part based on his wife, Hayrünnisa Gül, wearing the headscarf, and Gül’s opponents and supporters alike were acutely aware of this fact. Thus, the AK Party’s resounding victory in the 2007 elections, which was immediately followed by Gül’s election to the presidency in the parliament, was also a popular mandate for the removal of the headscarf ban, which was certainly in place in Turkey’s educational institutions, judiciary, military, police, the public sector at large, and even in most of the private sector.31

Not only did they do nothing in favor of emancipation, but the EU and the ECHR arguably contributed to justifying and prolonging the segregationist laws against religious conservatives in Turkey

It is an unforgettable stain on the European Union’s (EU) record that it did not pressure Turkey, in any consequential or substantial way, to remove the segregationist laws that prevented more than half of Turkish women from getting education or employment, or seeking elected office. Even worse, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), in a nearly unanimous ruling (16 in favor, one against) in the case of Leyla Şahin versus Turkey (2004), upheld the headscarf ban. Thus, not only did they do nothing in favor of emancipation, but the EU and the ECHR arguably contributed to justifying and prolonging the segregationist laws against religious conservatives in Turkey.

The first attempt to remove the headscarf ban brought the AK Party to the brink of closure in 2008. The constitutional amendment to remove the headscarf ban in education was proposed by the AK Party and the MHP, and approved by a super majority in the parliament in February 2008, with 411 voting for (presumably AK Party and MHP members, and a few more) and 103 members voting against (presumably all the CHP and DSP members, and a few more).32 The CHP members derided the legislation to remove the headscarf ban as Turkey’s “dark/black revolution” (kara devrim), explicitly comparing it to the Orange Revolution in Ukraine, and depicted the headscarf as “a political symbol and uniform that became the flag of imperialism.”33 Moreover, MPs of the CHP and the DSP appealed to the Constitutional Court in order to annul the constitutional amendment, and the court indeed did annul it in June 2008, with nine judges voting in favor and two judges voting against the annulment. Furthermore, the month after the passage of the constitutional amendment, in March 2008, the Public Prosecutor of the Supreme Court of Appeals opened a case to close down the AK Party for being “the focal point of anti-secular activities.” In July 2008, six judges voted in favor and five judges voted against the closure of AK Party, but since such a decision requires a qualified majority, the party narrowly escaped being shut down. This episode of intense political and judicial drama around the headscarf ban, which affected the civil and political rights of roughly sixty percent of Turkish women, was very instructive. It demonstrated that the main opposition party, the CHP, with only one-fifth of the popular vote and about one-fifth of the parliament, could effectively block the removal of the headscarf ban, despite a four-fifths majority in the parliament voting in favor of removal, and a popular opinion that was around seventy percent against and only around twenty percent in favor of the ban.34 This was in great part due to the “Republican” secularist hegemony in the judiciary, which had a decades-long history.35 As Ceren Belge argued, “far from leading a rights-revolution, the Constitutional Court of Turkey became renowned for its restrictive take on civil liberties”36 over many decades.

After the constitutional referendum that took place on 12 September 2010, the legislature and the executive branch acquired greater influence on the selection of high ranking judges, including those of the Constitutional Court, and this change gradually broke the secularist hegemony in the judiciary. Similarly, the AK Party’s third and most impressive landslide victory in 2011 (Table 1) consolidated its status as the dominant party in Turkish politics. Thus, in October 2013, the AK Party was sufficiently emboldened to abolish the headscarf ban in the public sector, except for the military, judiciary, and the police, which are governed by their own organizational statutes. As a result, four AK Party MPs entered the parliament wearing their headscarves following their return from pilgrimage to Mecca. This watershed in political history was met with great enthusiasm among the ranks of the AK Party, but had a lukewarm if not critical reception by the CHP. In the following years, the AK Party implemented other reforms that opened up the ranks of the judiciary37 (2015) and the police38 (2016) to women wearing headscarves. I would argue that these reforms, which opened up political office and employment opportunities for the majority of the Turkish women for the first time, are comparable to the Civil Rights Movement and the Voting Rights Act (1965) in the United States, which had both symbolic and substantive significance for the advancement of African Americans. Curiously, Freedom House did not increase Turkey’s democracy score in light of these historic reforms, as one would expect, and instead, it assigned a “downward trend arrow” for Turkey’s democratization in 2014.39 More strikingly, Polity IV dramatically lowered Turkey’s democracy score from 9 in 2013 to 3 in 2014, although more than half of the women gained the right to run for public office in late 2013.40

The Emancipation of Kurdish Citizens

The AK Party’s reforms allowing for the expression of Turkey’s long-suppressed ethno-linguistic diversity, which later became known as the “Kurdish Opening” or the “Democratic Opening,” included the inauguration of publicly-funded Kurdish language broadcasting on state television, followed by the introduction of Kurdish and five other minority languages as elective courses in public schools. These reforms were truly revolutionary in the Turkish context, since merely claiming that “Kurds” exist could lead to a prison sentence, as happened even to a former minister in the government in the 1980s.41 AK Party’s reforms were implemented against such a political historical background.

A tank crushes a car as people take to the streets in Ankara during the coup attempt. | AFP PHOTO / ADEM ALTAN

A tank crushes a car as people take to the streets in Ankara during the coup attempt. | AFP PHOTO / ADEM ALTAN

In June 2004, state television TRT 3 began broadcasting in Arabic, Bosniak, Circassian, Kurdish, and Zaza for a limited time, and in January 2009, TRT inaugurated an entire new TV channel, TRT 6 (later renamed TRT Kurdi), broadcasting full time in Kurdish seven days a week. Starting in the 2012-2013 academic year, a new elective course entitled, “Living Languages and Dialects” was instituted in public schools in order to facilitate the teaching of indigenous minority languages on demand, and as of 2015, the Abkhaz, Adyghe, Georgian, Kurdish, Laz, and Zaza languages were being offered. I previously discussed these reforms in detail and argued that the concatenation of three critical factors in the AK Party motivated and propelled the implementation of these reforms: Kurdish electoral support for the AK Party, combined with an Islamic multiculturalist discourse as the primary justification that convinced the non-Kurdish majority of the need for the reforms, armed with a hegemonic majority in the parliament that could overcome opposition by other political parties and unelected components of government (the military, the judiciary, and the bureaucracy).42

The AK Party’s reforms were motivated by an Islamic multiculturalist discourse and implemented by an Islamic inspired political party, which included many religious conservative Kurdish MPs

I disagree with those who argue that the EU played the critical democratizing role in this area, by emphasizing that the Turkish government undertook the most momentous reforms allowing for the expression and support of Kurdish identity (TRT Kurdi, elective Kurdish courses in public schools, removal of the Turkish pledge of allegiance) in the 2009-2013 period, many years after Turkey’s membership negotiations with the EU were frozen (in 2005), and when EU membership no longer ranked among the top concerns or priorities of the government, the popular media, or the broader public. Conversely, the EU did nothing to restart or expedite Turkey’s membership process, despite the Turkish government’s historic reforms during the 2009-2013 period.

In October 2013, the Turkish pledge of allegiance (Andımız), which began with “I’m a Turk” and ended with “how happy is the one who says, ‘I’m a Turk’” (a famous saying of Atatürk), was abolished as part of the AK Party’s democratization package, which also included the removal of the headscarf ban as discussed earlier. Prior to the reform, all elementary school students in Turkey were obligated to recite the pledge of allegiance every morning, a source of long-standing grievance held by many anti-Kemalists of various stripes, including ethnically assertive Kurds. The pledge of allegiance reform, along with others such as the restitution of the original Kurdish names of villages, allowing Kurdish names for newborns, and the like, which addressed specifically Kurdish grievances, provided the most momentous, positive change in state policies toward ethnic diversity in Turkey’s history. More significantly, these reforms turned the PKK into “terrorists without a cause,” since all the major state policies criminalizing the Kurdish language and culture were annulled, and the state even began to actively support the revival of the Kurdish language and identity through public resources, a move similar to the ethnically-specific affirmative action policies found in some other countries. The AK Party’s reforms were motivated by an Islamic multiculturalist discourse and implemented by an Islamic inspired political party, which included many religious conservative Kurdish MPs. This makes the AK Party leaders comparable to leaders of the civil rights struggle in the United States such as Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X, who used religious discourse (Christian and Islamic, respectively) for the advancement of African American rights.

Secularist and Nationalist Resentment in Opposition: Between Reaction and Reconciliation

By being the only party that staked its existence on lifting the headscarf ban, the AK Party captured the moral high ground in what was arguably the most pivotal issue of Turkish politics. The AK Party took this chance in response to its electorate, which had been actively demanding the removal of segregationist measures against religious conservatives for decades. As long ago as the 1950s, several political parties became the conduit of similar demands for ending segregation, the Democratic Party (DP) holding a place of prominence among them. However, the major opposition parties that currently dominate Turkish politics, including the Kemalist CHP, the nationalist MHP, and the Kurdish socialist BDP (later renamed as HDP), never prioritized the removal of the headscarf ban as one of their top goals. From an electoral demographic standpoint, such a stance is somewhat inexplicable, since at least half of the women who vote for the MHP and the Kurdish socialists wear a headscarf, and about thirty percent of the women who vote for the CHP also do so. The explanation of the CHP’s visceral stance in favor of the headscarf ban and its effective opposition to its removal is based on their understanding of secularism, or laïcité. In the case of the BDP (the HDP’s predecessor), the party’s Kurdish socialist ideology, originally inspired by the Soviet experience, and its identification with the Bolshevik Revolution, may have suppressed any pressures that the party may have felt from its female electorate. Unlike the CHP, which supported the ban, and the MHP, which voted with AK Party for its removal, the Kurdish socialists remained bystanders on the sidelines during the dramatic showdowns over the headscarf ban.

Once the headscarf ban was finally removed in October 2013, all the major parties maintained that they had been against the ban all along. However, in the next general elections in June 2015, the CHP nominated 103 women candidates,43 but not a single one of them was wearing a headscarf. In the following November 2015 general elections, the CHP nominated 125 female candidates, none of whom wore the headscarf. In a country where roughly sixty percent of women wear the headscarf, the CHP’s failure to nominate a single woman with a headscarf among its more than one hundred candidates in the two elections following the removal of the headscarf ban is stunning, and also reveals the party’s continuing exclusionary attitude. In contrast, the AK Party nominated dozens of women wearing headscarves, and 19 of them were elected into the parliament in the very first elections after the ban was lifted in June 2015.44

In a country where roughly sixty percent of women wear the headscarf, the CHP’s failure to nominate a single woman with a headscarf among its more than one hundred candidates in the two elections following the removal of the headscarf ban is stunning, and also reveals the party’s continuing exclusionary attitude

The opposition parties nonetheless made limited overtures at reconciliation by tacitly accepting most aspects of these reforms. For example, the MHP did not engage in a sustained effort, either through popular mobilization or judicial channels, to reverse the “Kurdish Opening” or to deprive Kurdish, Zaza, Arabic and other minority languages of public support. In contrast, the CHP appealed to the judiciary at multiple critical junctures to annul and reverse the AK Party’s attempts to lift the headscarf ban in different sectors. However, the CHP took a seemingly reconciliatory turn in early 2014, when it nominated some religious conservatives as its candidates in the local elections, including Mansur Yavaş (candidate for the mayor of Ankara) and İhsan Özkes (candidate for the mayor of Üsküdar); these candidates performed far better than CHP candidates in previous elections. Most prominently, the CHP and the MHP jointly nominated a religious conservative, Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu, former Secretary General of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, as their presidential candidate in 2014. İhsanoğlu received 38.4 percent of the vote, an unprecedented electoral peak for a non-AK Party politician, but still insufficient to force a second round against Tayyip Erdoğan, who was elected president by receiving 51.8 percent of the vote in the first round. Despite the moderate successes of the reconciliation with religious conservatives in 2014, the CHP abandoned this path in 2015, and instead sought a rapprochement with the Kurdish socialist HDP. Prominent religious conservative CHP candidates such as İhsanoğlu and Özkes severed their affiliation with the party; Özkes resigned from the CHP in protest, whereas İhsanoğlu joined the MHP and was twice elected as its MP from İstanbul in 2015. The HDP’s reaction to the AK Party’s reforms was more convoluted because of this party’s relationship with the PKK, and the existential crisis of the latter due to these reforms, which will be discussed in the next section.

Other reforms are necessary to secure the remaining rights of religious conservatives and ethno-linguistic minorities such as the Kurds. However, the reforms that have been implemented so far are most likely irreversible. Once the Democrats allowed the call to the prayer to be read out in Arabic in 1950 (as it is in all other Muslim countries), no other government or military dictatorship in later decades could ban the Arabic call to prayer again. Thus, it is unlikely that future governments will be able to ban Kurdish or exclude women wearing headscarves from Turkey’s public institutions.

Some reformist Turkish governments in the past, including the AK Party, had tactically cooperated with the Gülenists and even negotiated with the PKK, thinking that these groups could be allies in the emancipation of ethnic and religious expression in Turkey. However, these tactical alliances were paradoxical in nature, because a comprehensive solution that emancipated ethnic and religious expression through legal and peaceful channels would eradicate the grievances that the Gülenists and the PKK had exploited in their recruitment, and would pose an existential threat to the survival of the Gülenists and the PKK as such.

The Existential Crisis of the PKK and its Reactionary Offensive, July 2015

Every terrorist organization, and organized crime in general, starts out by exploiting a real grievance. Prohibition in the United States (1920-1933) created an opportunity space for the mafia to flourish in order to organize the illegal production, transportation, and sale of alcohol. In post-Soviet Russia, the state’s failure to enforce contracts and protect property rights created an environment conducive for the meteoric rise of the Russian mafia in the early 1990s, which led Vadim Volkov to describe the mafia as “violent entrepreneurs.”45

Republican policies that criminalized the public expression of religiosity and ethnic identity in Turkey created an environment conducive for the growth of criminal and violent organizations such as the PKK and the Gülenist cult. It is not coincidental that the PKK and the Gülenists experienced meteoric growth under the 1980 military dictatorship and in the 1990s, two periods when the expression of ethnic and religious expression was particularly suppressed. The PKK relied on the denial of Kurdish identity by the state in its recruitment of young Kurds as terrorists. Thus, the AK Party’s recognition of Kurdish identity, followed by explicit state support for Kurdish language and culture, posed an existential threat to the PKK. With Kurdish and Zaza being offered in public schools and broadcast with public funding, the PKK could no longer make a credible argument that the state is aiming to eradicate Kurdish identity. On the contrary, TRT Kurdi and the religious conservative Kurdish MPs and members of the AK Party arguably represented a more authentic, indigenous, and deeply rooted Kurdishness than the Bolshevik-inspired, socialist, and avowedly secularist if not atheist version of Kurdishness propagated by the PKK. The militarized one-party regime that the PKK and the PYD sought to establish in southeastern Turkey and northeastern Syria, respectively, can be described as a “belated Kurdish Soviet experiment.”46 Thus, hundreds of thousands of Kurdish dissidents escaped from the territories that came under PYD control in Syria, and sought refuge in Turkey and the Kurdish Regional Government in Iraq.

The international media not only failed to acknowledge these incidents as an ideological pogrom by PKK sympathizers against their opponents, they even distorted the facts in order to depict it as a conflict between the Turkish police and the Kurdish minority

Starting in October 2014, the PKK began to experiment with creating a similarly militarized one-party regime within Turkey. In 6 October 2014, the HDP Central Committee called on “our peoples to protest ISIS and the AK Party government” regarding the siege in Kobani.47 HDP and PKK sympathizers terrorized the cities and towns of southeast Turkey, publicly lynching dozens of their political opponents, mostly religious conservative Kurds.48 The case of Yasin Börü, a 16 year-old who was chased while distributing free meat to the poor as part of an Islamic charity, and was tortured to death by PKK sympathizers, gained some national recognition. A psychologist found the nature of these collective lynchings against PKK opponents to be comparable to the genocide in Rwanda on a micro scale.49 However, the international media not only failed to acknowledge these incidents as an ideological pogrom by PKK sympathizers against their opponents, they even distorted the facts in order to depict it as a conflict between the Turkish police and the Kurdish minority.50 The lynchings of those who opposed the Kurdish socialist project of the PKK are similar to the Ku Klux Klan’s lynchings of blacks in the American South in order to reproduce the Jim Crow regime.

The AK Party’s expansion of Kurdish rights had been met with increased PKK violence in the past as well, especially after the AK Party gained the electoral support of a clear majority among Kurdish voters in 2007, which posed an existential challenge to the PKK’s claim of being the sole representative of the Kurds.51 As Güneş Murat Tezcür argued, “democratization will not necessarily facilitate the end of violent conflict as long as it introduces competition that challenges the political hegemony of the insurgent organization over its ethnic constituency.”52 Thus, it is not surprising that PKK attacks increased after the AK Party introduced major reforms to expand ethnic Kurdish expression.

Members of the Gülenist cult were instructed to practice an extreme form of public dissimulation to pass as non-religious, irreligious, or even anti-religious people, in order not to attract the ire of the secularist regime

The PKK initiated its most recent and violent offensive on July 11, 2015, with the KCK (an umbrella organization of the PKK) declaring that it is unilaterally ending the ceasefire because of the hydroelectric “dams with a military purpose” that the government was allegedly building.53 This was followed by the editorial of Bese Hozat, the chairwoman of the KCK, who declared that “the new process is a Revolutionary People’s War” in the leading newspaper affiliated with the PKK.54 As historian Halil Berktay argued, it would be more appropriate to term the PKK’s offensive a “counterrevolutionary war,” as it sought to overthrow a government that had granted the most substantial rights for Kurds in Turkish history.55 Although the long term, structural cause of the PKK’s attacks were the AK Party’s reforms that sought to eradicate the ethnic grievances that the PKK exploited, the short term cause may have been to protect the one-party dictatorship that the PYD had established in northeastern Syria. Between the June and November 2015 elections, the HDP lost more than one million votes, corresponding to 2.3 percent of the national electorate (Table 1), a loss which most observers attributed to the unpopularity of the PKK’s offensive. Nonetheless, after the elections, the PKK intensified its attacks and turned to urban warfare by digging trenches around several Kurdish towns, which led to the mass flight of hundreds of thousands of Kurdish civilians from these urban centers. Kurdish masses demonstrated their resistance to and disapproval of the PKK’s offensive by not following the PKK’s call for a popular uprising. They simply did not participate in the PKK’s activities, showing their disapproval by non-violent, civil disobedience to the PKK’s demands. The Turkish army inflicted very heavy losses on the PKK in this struggle, and the PKK increasingly resorted to suicide bombings in urban centers that killed 285 civilians, including eleven children, as of March 2016.56 In sum, by early 2016, the PKK’s reactionary offensive against Turkey and their effort to create a militarized, one-party regime in southeast Turkey had utterly failed.

The Existential Crisis of the Gülenist Cult and its Reactionary Coup, July 2016

The removal of the discriminatory measures against religious conservative citizens posed an existential threat to the Gülenist cult as their clandestine hierarchy (based on “older brothers/sisters,” explained further below) and criminal activities were previously justified as a necessity in order to survive under an illiberal secularist regime persecuting public expressions of religious piety. Members of the Gülenist cult were instructed to practice an extreme form of public dissimulation to pass as non-religious, irreligious, or even anti-religious people, in order not to attract the ire of the secularist regime. According to one high-ranking defector from the Gülenist cult, these practices of public dissimulation (takiyye) included drinking alcohol and swimming in a bikini (for women),57 and avoiding any outward expressions of Islamic religiosity such as keeping a beard for men or wearing a headscarf for women.

Two women, with differing lifestyles choices but united in their defense of democracy, wave Turkish flags to celebrate the victory of the people against the coup plotters, in the Southern city of Adana. | AA PHOTO / SERHAT ÇAĞDAŞ

Two women, with differing lifestyles choices but united in their defense of democracy, wave Turkish flags to celebrate the victory of the people against the coup plotters, in the Southern city of Adana. | AA PHOTO / SERHAT ÇAĞDAŞ

Who are the members of the Gülenist cult? One can be considered a member if one is taking orders from a Gülenist “older brother/sister” (akin to a spiritual commissar) assigned to him/her, instead of following the orders of his/her superior in the legal hierarchy, such as the military chain of command, as he/she should. This is what is meant by a “parallel state,” with its own illegal hierarchy, which is now implicated in major criminal activities within the military, judiciary, police, and other state institutions.

The Gülenists are implicated in several different kinds of criminal activities currently under investigation. Arresting and prosecuting their opponents in show trials constitute the most publicly known crime in which the Gülenists are implicated.58 Mass cheating through the distribution of the answer keys of national entrance examinations59 for universities, military academies, and employment in public service constitute another type of crime, which resulted in perfect or near perfect test scores for many Gülenists, and disadvantaged millions of ordinary citizens who took these examinations over many years and even decades, in the case of the military academies.60 The wiretapping and videotaping of the private conversations and affairs of thousands of people in order to blackmail them constitutes yet another kind of crime in which the Gülenists are implicated.61

The Gülenists are also implicated in the assassinations of anti-Gülenist scholar Necip Hablemitoğlu,62 and the famous Turkish-Armenian intellectual and journalist Hrant Dink. Nedim Şener, a prominent journalist who wrote books and articles about the role of the Gülenists in the murder of Hrant Dink, was put in prison as a result of a show trial, which, he argues, was orchestrated by the Gülenists.63

The primary cause of the Western media outlets’ misleading coverage of the failed coup was their inability or unwillingness to accept the fact that mostly religious, conservative masses in a predominantly Muslim country saved democracy by fighting against an emergent military dictatorship

The leading role of the Gülenists in the coup attempt of July 15 is corroborated by numerous testimonies of leading officers in the Turkish army, both those who participated in the coup, and those who resisted it.64 Dani Rodrik argued that the testimony of Hulusi Akar, the chief of staff of the Turkish military, may itself be sufficient for the extradition of Fetullah Gülen from the United States,65 since Akar explicitly stated that the coup plotters offered to put him on the phone with Gülen, “our opinion leader.”66 Testimonies pointing to the Gülenist takeover of the military through purges of leading anti-Gülenist officers predate the coup attempt, and these criticisms were usually made by staunch opponents of the AK Party government, two critical facts that lend additional credence to these claims. Colonel Judge Ahmet Zeki Üçok had already prepared a list of Gülenist officers back in 2009, but was imprisoned for 4 years and 9 months by Gülenist judges.67 Both Colonel Üçok, and the Gülenist Lieutenant Colonel Levent Türkkan, who took the Chief of Staff hostage during the coup attempt, concur that the Gülenists were already stealing and distributing the answer key of the military schools’ entrance examinations as far back as 1986, thirty years before the coup attempt.68

Since their societal support is marginal, Gülenist coup plotters tried to woo the secularists to their side by emphasizing secularism and the principles of Atatürk in the coup manifesto they broadcasted from TRT during the coup attempt. Yet they utterly failed in this effort, as there was absolutely no popular mobilization in favor of the coup. The assassination attempt against president Erdoğan, which occurred on the night of the coup, was planned in minute detail, since the assassins even knew the exact rooms of the vacation resort where the police protecting Erdoğan were staying, and they indeed stormed those rooms, killing one policeman and torturing the rest, who remained in critical condition.69 Erdoğan barely survived by leaving the resort slightly prior to the attack. He then connected to a national TV station through Facetime, where he urged the nation to resist the coup attempt. Masses of citizens rushed to the main avenues, and secured critical locations such as the main airport and TV stations, blocking the coup plotters’ advance. 240 people were killed that night while fighting against the coup plotters.

The Western Media’s Islamophobic Misperceptions and Ambiguous Reactions to the Coup

The reporting of the Western media regarding the coup attempt and the heroic civilian resistance that defeated it in Turkey was disappointing at best. One Turkish website critical of the Western media coverage already has a “Wall of Shame” that brings together some of the anti-democratic “news” stories and opinion columns regarding the failed coup in Turkey.70

The primary cause of the Western media outlets’ misleading coverage of the failed coup was their inability or unwillingness to accept the fact that mostly religious, conservative masses in a predominantly Muslim country saved democracy by fighting against an emergent military dictatorship. This inability or unwillingness is based on the Islamophobic assumption that religiously-inspired masses in Muslim countries, unlike religiously-inspired African American Protestants or Mexican Catholics, for example, are inherently anti-democratic. On the contrary, there have been many religiously-inspired movements, Christian and Muslim alike that have fought historically against totalitarian communism, racial segregation, and secular military dictatorships. Just as the activists of the Civil Rights Movement often sang an originally religious hymn, “We Shall Overcome,” in their struggle for equality, some Turks were also yelling religious slogans in their struggle for equality in resisting the coup attempt.

The misrepresentation of Turkish politics by the standard bearers of the Western media such as the New York Times (US), the Economist (UK), and Der Spiegel (Germany), hit an all-time low in their coverage of the coup attempt, failing to recognize that an existential threat against democracy had been thwarted. 240 people, including 173 civilians, 62 policeman, and 5 soldiers, sacrificed their lives while defending democracy against the coup plotters.71 All of the political parties in the Turkish parliament condemned the coup attempt, and the leaders of the AK Party, the CHP, and the MHP spoke out against the coup on the night of July 15-16. Putschist pilots bombed the parliament. At a minimum, one would expect democratic media outlets to publish a principled and unconditional condemnation of the coup plot and a celebration of the Turkish people who defeated it, including President Erdoğan, who mobilized the nation against the coup attempt.

Instead of celebrating the heroism of the citizens, who took to the streets in order to defend their democratically elected government, however, the New York Times chose to belittle if not smear them by tweeting that, “those who took to streets in Turkey were mostly yelling religious slogans in support of Erdoğan not democracy itself.”72 What the New York Times failed to understand or deliberately obscured is that ordinary people shouting any slogans – religious or secular – in support of a democratically-elected leader against an ongoing military coup, and risking their lives by doing so, should be considered a courageous democratic stance in and of itself.

President Erdoğan was the key leader who first called on the nation to resist the coup plot. This did not have to be the case. For example, it was Boris Yeltsin who assumed the leadership of the movement that defeated the coup against his incumbent political rival, Mikhail Gorbachev, in August 1991, effectively enabling him to definitively eclipse Gorbachev in the waning years of the Soviet Union.73 Thus, counterfactually, one of Turkey’s opposition party leaders could have taken to the streets and led the popular mobilization against the coup, but, significantly enough, this did not happen. Moreover, a large majority of the people who actively mobilized against the coup plotters were AK Party voters;74 further, “mosques, in addition to digital media, played a significant role in mobilizing Turks who were against the coup.”75 More dramatically, President Erdoğan’s long-time campaign manager and his son were among those who lost their lives while resisting the coup plotters, as did a professor who was the elder brother of a presidential advisor. However, the Economist inverted this reality by headlining its story as follows: “Erdoğan’s revenge: Turkey’s president is destroying the democracy that Turks risked their lives to defend.”76 This is not only terrible journalism that contradicts the factual details of the coup attempt and how it was defeated, it is also insulting to the political sentiments of the masses who mobilized, and those who died, fighting against the military coup.

The influential German weekly, Der Spiegel, published a cover story about the coup in Turkey, provocatively embellished with a Turkish flag behind barbed wire, and entitled “It was once a democracy: Dictator Erdoğan and the helpless West.”77 Looking at the cover of Der Spiegel, one would think that the coup had succeeded in installing a military dictatorship, which then promptly began executing dissidents. In reality, the three largest parties banded together to hold a spectacular rally attended by millions of citizens in İstanbul on 7 August 2016, to mark the finale of three weeks of nationwide rallies to commemorate the popular victory against the coup plotters.

Hopefully, the failure of the coup in Turkey will have felicitous effects in emboldening democratic movements across Muslim-majority polities around the world

The western media’s incomprehension and misrepresentation of the role that the AK Party and Erdoğan play in Turkish politics is not limited to the coverage of the recent coup attempt. As I argued in detail above, the AK Party had occupied the moral high ground in Turkish politics for a long time before the coup, although one would not know it from reading the Western media. If Erdoğan and the AK Party were as oppressive as the Economist and Der Spiegel make them seem, why do they remain by far the most popular leader and the most popular political party in Turkey, having won nine national elections (five parliamentary, three local/municipal, one presidential) and two national referenda since 2002? Turkish elections are free, fair and very competitive by all international standards. The competitiveness of the elections is also proven by the fact that many opposition parties win resounding victories at the local and regional levels, and their national support also rises and falls significantly, as we most recently witnessed between June and November 2015. Is there any “dictator” in modern history that has won eleven genuinely competitive multiparty contests spread across a decade-and-a-half?78 This a key question to motivate some critical thinking about the Western media coverage of Erdoğan and the AK Party.

The answer should be obvious for anyone who lived through the legal discrimination and institutional segregation that religious conservatives and ethnic minorities had to endure before the AK Party came to power. As previously noted, the headscarf ban alone affected roughly sixty percent of Turkish women. Moreover, the popular mandate that a political party or a leader earns due to their democratizing role at a critical juncture may last for a generation, or even several generations, as one observes in the United States and South Africa.79 Any analysis or criticism of Erdoğan and the AK Party that overlooks the massive political capital they gained as a result of their leading role in the democratic emancipation of historically disadvantaged groups in Turkey is likely to be incomplete and therefore misleading.

The Failed Coup in Turkey as a World Historical Event

The successful mobilization against the coup attempt in Turkey has a world historical significance for several reasons. First, it is very rare for a military coup with such extensive domestic and international connections to be defeated by a popular mobilization. The failure of the coup attempt against Hugo Chavez in Venezuela in 2002 is a similar rare case, but there are not many others. Mohammad Mosaddegh of Iran and Salvador Allende of Chile are prime examples of popular and democratically elected leaders who were overthrown in military coups that were supported by the United States in 1953 and 1973, respectively.80 Second, the failure of the coup in Turkey went against the previous trend of counterrevolutionary coups and recent repression in the Middle East, most notably observed in the successful coup against Mohamed Morsi’s democratically elected civilian government in Egypt in July 2013. Hopefully, the failure of the coup in Turkey will have felicitous effects in emboldening democratic movements across Muslim-majority polities around the world. It is also noteworthy and significant that Turkey has been the most vocal (and almost only) country to openly denounce the coup in Egypt, and has sided with the democratically elected government of Mohamed Morsi for the last three years, whereas the United States, Russia, France, Saudi Arabia, and Germany, among others, were quick to embrace and endorse the military dictatorship of Sisi. Third, the massive civilian resistance against the coup enshrined “democracy” as a precious national ideal to fight and die for in Turkey, as public commemorations for the “martyrs of democracy” attest, which is an enormous step for the consolidation of democracy as a political system.

The coup attempt threatened to undo the hard-won equality and democratic progress of previous decades, and should be considered reactionary and regressive as such

The coup attempt threatened to undo the hard-won equality and democratic progress of previous decades, and should be considered reactionary and regressive as such. In this article, I have highlighted the historic reforms that emancipated religious conservatives and ethnic minorities such as the Kurds from their status as second-class citizens. The popular resistance against the coup attempt, led by Erdoğan and the AK Party, but which also included all of the major political parties in Turkey, consolidated the moral high ground of democracy in Turkish politics. The western media outlets’ hostile and distorted coverage of Erdoğan’s key role in defeating the coup attempt, and their suspiciously equivocal attitude vis-à-vis the coup plotters, has antagonized and alienated the Turkish public, even provoking Turkish elites and ordinary citizens alike to question Turkey’s place in the Western alliance.81

Endnotes

- “Silent Revolution” is the title the AK Party itself uses to refer to the democratic reforms it has undertaken. See the party’s publication with the same title, Sessiz Devrim: Türkiye’nin Demokratik Değişim ve Dönüşüm Envanteri (2002-2012), (2013), retrieved from www.akparti.org.tr/upload/

documents/sessiz_devrim.pdf. - According to a widely acclaimed study by Ali Çarkoğlu and Binnaz Toprak, Turkish women who did not cover their heads were 27.3 percent in 1999 and 36.5 percent in 2006. Thus, women who covered their heads made up 72.7 percent in 1999, and 63.5 percent in 2006. Çarkoğlu and Toprak also subdivided those who covered their heads into variants of headscarf alone (eşarp, başörtüsü, yemeni, worn by 48.8 percent in 2006), full body veil (çarşaf, or chador in English, worn by only 1.1 percent in 2006), and turban (worn by 11.4 percent in 2006). These are the figures I have in mind throughout this article, whenever I refer to “roughly sixty percent” of Turkish women wearing headscarves. See Ali Çarkoğlu and Binnaz Toprak, “Din, Toplum ve Siyaset,” TESEV, (November 16, 2006), retrieved from http://tesev.org.tr/wp-

content/uploads/2015/11/ Degisen_Turkiyede_Din_Toplum_ Ve_Siyaset.pdf, p. 24. - PKK was illegal all along, and the parallel hierarchy of the Gülenist cult, consisting of “older brothers/sisters” giving orders to public servants in defiance of their legal superiors, was likewise clandestine and illegal all along. Moreover, the Gülenist cult was considered a terrorist organization in Turkish courts starting in late 2015.

- In a similar vein, Halil Berktay refers to the PKK’s offensive and the failed coup as counterrevolutionary attempts, a designation, which is in conformity with the AK Party’s self-identification as the agent of a “silent revolution” (see the first endnote), an interpretation that I mostly agree with. Nonetheless, I think “civil rights movement” is a better label for the democratic, gradual, legal, and non-violent emancipation process in Turkey, compared to the concept of a revolution, which has been frequently used and abused to refer to violent, anti-democratic coups by ideological minorities, such as the Bolshevik “Revolution.” See Halil Berktay, “Suruç’un Ardından (2) PKK’nın Yeni Karşı-devrimci İç Savaşı,” Serbestiyet, (July 24, 2015), retrieved from http://serbestiyet.com/

yazarlar/halil-berktay/ surucun-ardindan-2-pkknin- yeni-karsi-devrimci-ic-savasi- 157112 and Halil Berktay, “İkinci Cumhuriyet’ten, Yeni Türkiye’ye,” Serbestiyet, (August 2, 2016), retrieved from http://serbestiyet.com/ yazarlar/halil-berktay/ikinci- cumhuriyetten-yeni-turkiyeye- 708272. - I chose the term “secularist” to describe a particularly narrow interpretation of secularism, which defines it as a way of life that even encompasses individuals’ choices in their private affairs. This is markedly different than the meaning of “secular” as referring to the political condition of separation between religion and state. The overwhelming majority of Turks, including most religious conservatives, are “secular” in this conventional sense, as they support the separation of religion, state, and the legal system.

- Anthony W. Marx, Race and Nation: A Comparison of the United States, South Africa, and Brazil, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

- Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, (New York: The New Press, 2012). Especially see the introduction where she discusses the eerie parallels in social control directed particularly against black males during slavery, segregation, and throughout the “Drug Wars,” which disproportionately targeted black males, presenting a historical parallel that the black inmates also noted.

- “National” is a debatable translation for “Milli” but I used it for the sake of simplicity, abiding by the prevailing usage in almost all translations. “Milli” can also be translated as “religious” instead, since “millet” denoted religious community in 1919-1922. For a critical take on this translation, see my article and book cited in the following endnotes.

- Şener Aktürk, “Religion and Nationalism: Contradictions of Islamic Origins and Secular Nation-Building in Turkey, Algeria, and Pakistan,” Social Science Quarterly, Vol. 96, No. 3 (2015), pp. 778-806.

- Aktürk, “Religion and Nationalism.”

- Şener Aktürk and Adnan Naseemullah, “Carving Nation from Confession: Haven Nationalism and Religious Backlash in Turkey, Israel, and Pakistan,” APSA 2009 Toronto Meeting Paper, available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=

1449143. - The formulation by Edward Shils, where he argued that every society has a center and a periphery, has been famously applied to the case of Turkey. See Edward Shils, “Centre and Periphery,” in The Logic of Personal Knowledge: Essays Presented to Michael Polanyi, (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1961), pp. 117-131. For the application of this framework to Turkey, see Şerif Mardin, “Center-Periphery Relations: A Key to Turkish Politics?,” Daedalus, (1973), pp. 169-190.

- See endnote 2 for Çarkoğlu and Toprak’s famous study on religion, society, and politics in Turkey, which is the source of my estimates for the prevalence of headscarves.

- Mustafa Kemal Atatürk attended Friday prayers during the National Struggle, and in the early years of the Republic in the 1920s, when Islam was still the religion of state.

- “Din İstismarı Yapmayan Dindar: İsmet İnönü,” OdaTv, (May 13, 2011), retrieved from http://odatv.com/din-

istismari-yapmayan-dindar- ismet-inonu--1305111200.html. - “Devlet Başkanı Namaz Kılar Mı Hiç!,” A-Haber, (October 30, 2011), retrieved from http://www.ahaber.com.tr/

gundem/2011/10/30/devlet- baskani-namaz-kilar-mi-hic. - Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, İsmet İnönü, Cemal Gürsel, Cevdet Sunay, Fahri Korutürk, and Kenan Evren were former military officers. The only exception among the first seven presidents was Celal Bayar (1950-1960).

- Celal Bayar, the only civilian president among the first seven presidents, was also known as a staunch secularist and an ardent follower of Atatürk who stated that, “loving Atatürk is a form of worship.” Although Bayar and the DP he led received the religious conservative vote, and had a more liberal understanding of secularism than their predecessor the CHP, Bayar was also known not to perform the Islamic daily prayers. “Said Nursi’nin Celal Bayar’a İlk Sorusu: Namaz Kılıyor Musun?,” Risale Haber, (March 20, 2014), retrieved from http://www.risalehaber.com/

said-nursinin-celal-bayara- ilk-sorusu-namaz-kiliyor- musun-205899h.htm. - The controversy surrounding Merve Kavakçı’s attempt to enter the parliament as an MP wearing the headscarf in 1999 is very well known. She was promptly forced to leave the parliament building, and soon officially expelled from parliament, even though she was an elected representative. See her book on this issue: Merve Kavakçı İslam, Headscarf Politics in Turkey: A Postcolonial Reading, (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010).

- Senem Aslan, Nation-Building in Turkey and Morocco: Governing Kurdish and Berberissent, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

- Zafer Toprak, “Atatürk’ün Kürt Sorunu Değil Din Sorunu Vardı,” Radikal, (April 9, 2012), retrieved from

http://www.radikal.com.tr/yazarlar/ezgi-basaran/ ataturkun-kurt-sorunu-degil- din-sorunu-vardi-

1084339/. - Vahdettin İnce, Kürdinsan, (İstanbul: Beyan, 2016). Also see the next five footnotes.

- Müfit Yüksel, İslamsız Kürdistan Hayali ve Ortadoğu, (İstanbul: Etkileşim, 2015).

- Fehmi Çalmuk, Erbakan’ın Kürtleri, (İstanbul: Metis, 2001).

- Ümit Cizre Sakallıoğlu, “Kurdish Nationalism From an Islamist Perspective: The Discourses of Turkish Islamist Writers,” Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, Vol. 18, No.1 (1998), pp. 73-89.

- Burhanettin Duran, “Approaching the Kurdish Question via Adil Düzen: An Islamist Formula of the Welfare Party For Ethnic Coexistence,” Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, Vol. 18, No. 1 (1998), pp. 111-128.

- Muhittin Ataman, “Islamic Perspective on Ethnicity and Nationalism: Diversity or Uniformity?,” Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2003), pp. 89-102.

- The largest Turkish nationalist opposition party, the MHP, also has an identity story and self-perception as being comprised of second-class citizens in the “Turkish” state. The party’s founder and leader for almost three decades, retired colonel Alparslan Türkeş, was tried and imprisoned in 1944-1945 in the “racism-Turanism” trials, and was also imprisoned for over four years after the 1980 military coup. Many MHP members were executed after the 1980 coup. Intriguingly, these and other similar episodes breed the sense of being “second-class” citizens among Turkish ultranationalists. The MHP’s electoral base can be considered conservative, and the party supported the removal of the headscarf ban and other similar initiatives to end the segregation of religious conservatives.

- Şener Aktürk, “Persistence of the Islamic Millet as an Ottoman legacy: Mono-religious and Anti-ethnic Definition of Turkish Nationhood,” Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 45, No. 6 (2009), pp. 893-909.

- More symbolically, an Armenian columnist was appointed chief advisor to the Prime Minister, and another Armenian journalist was nominated and elected (twice) as a member of parliament from the AK Party.

- Dilek Cindoğlu, “Headscarf Ban and Discrimination: Professional Headscarved Women in the Labor Market,” TESEV, (2011), p. 5: “The headscarf ban applied in institutions of higher education, in the public sector, and as this research has shown, in the private sector…” retrieved from http://tesev.org.tr/wp-

content/uploads/2015/11/ Headscarf_Ban_And_ Discrimination.pdf. - “Türban Meclis’ten Geçti,” Milliyet, retrieved from http://www.milliyet.com.tr/

Siyaset/HaberDetay.aspx?aType= HaberDetayArsiv&KategoriID=4& ArticleID=238997&PAGE=1 and “411 El Kaosa Kalktı” (headline), Hürriyet, (February 10, 2008), retrieved from https://upload.wikimedia.org/ wikipedia/tr/8/

83/H%C3%BCrriyet_Gazetesi_10_%C5%9Eubat_2008.jpg. - “Türban Meclis’ten Geçti,” Milliyet.

- Çarkoğlu and Toprak, “Din, Toplum ve Siyaset,” p. 71. As of 2006, only 19.4 percent supported the headscarf ban in the universities, whereas 71.1 percent opposed it. Likewise, only 22.3 percent supported the headscarf ban for public servants, whereas 67.9 opposed it.

- Ceren Belge, “Friends of the Court: The Republican Alliance and Selective Activism of the Constitutional Court of Turkey,” Law & Society Review, Vol. 40, No. 3 (2006), pp. 653-692.

- Belge, “Friends of the Court,” p. 653.

- “Hakim ve Savcıya Başörtüsü İzni Çıktı,” Milliyet, (June 1, 2015), retrieved from http://www.milliyet.com.tr/

hakim-ve-savciya-basortusu- izni-gundem-2067366/. - “Artık Polislerde de Başörtüsü Serbest,” Sabah, (August 27, 2016), retrieved from http://www.sabah.com.tr/

gundem/2016/08/27/artik- polislerde-de-basortusu- serbest. - “Turkey – Country Report,” Freedom in the World 2014, retrieved from https://freedomhouse.org/

report/freedom-world/2014/ turkey. - For purposes of comparison, note that Turkey’s polity2 score was 7 in 1984 and 1997, two years of extraordinary military tutelage. “Polity IV: Regime Authority Characteristics and Transitions Datasets,” Annual Time-Series, 1800-2015, Excel Series, column K (“polity2”), retrieved from http://www.systemicpeace.org/

inscrdata.html. - Şener Aktürk, “Regimes of Ethnicity: Comparative Analysis of Germany, the Soviet Union/Post-Soviet Russia, and Turkey,” World Politics, Vol. 63, No. 1 (2011), pp. 115-164.

- Şener Aktürk, Regimes of Ethnicity and Nationhood in Germany, Russia, and Turkey, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

- “Partilerin Kadın Milletvekili Adayı Sayıları,” Birgün, (September 19, 2015), retrieved from http://www.birgun.net/haber-

detay/partilerin-kadin- milletvekili-adayi-sayilari- 89969.html. - At the time this article was being written in September 2016, the AK Party had 34 women elected in its parliamentary caucus, including 20 who wore a headscarf, and 14 who did not. See <https://www.akparti.org.tr/

kadinkollari/milletvekilleri>. - Vadim Volkov, Violent Entrepreneurs: The Use of Force in the Making of Russian Capitalism, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2002).

- Şener Aktürk, “The PKK and the PYD’s Kurdish Soviet Experiment in Syria and Turkey,” Daily Sabah, (January 27, 2016), retrieved from http://www.dailysabah.com/op-

ed/2016/01/27/the-pkk-

and-pyds-kurdish-soviet-experiment-in-syria-and- turkey. - See the direct tweet from the HDP central committee, which is the source for the quotation: https://twitter.com/

hdpgenelmerkezi/status/ 519175390443474944. - Yıldıray Oğur, “PKK’nın Cadı Avı,” Türkiye, (October 10, 2014), retrieved from http://www.turkiye

gazetesi.com.tr/yazarlar/yildiray-ogur/582643.aspx. - Medaim Yanık, “6-7 Ekim Olaylarının Sosyal Psikolojisi,” Sabah, (October 18, 2014), retrieved from http://setav.org/tr/6-7-ekim-

olaylarinin-sosyal- psikolojisi/yorum/17631. - “Riots in Turkey Kill 19 over Failure to Aid Besieged Syrian Kurds,” Newsweek, (October 8, 2014), retrieved from http://europe.newsweek.com/

riots-turkey-kill-19-over- failure-aid-besieged-syrian- kurds-276115?rm=eu. - Güneş Murat Tezcür, “When Democratization Radicalizes? The Kurdish Nationalist Movement in Turkey,” Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 47, No. 6 (2010), pp. 775-89.

- Tezcür, “When Democratization Radicalizes?,” p. 775.

- “KCK Ateşkesin Bittiğini Açıkladı: Bundan Sonra Tüm Barajlar Gerillanın Hedefinde Olacaktır,”

T24, (July 11, 2015), retrieved from http://t24.com.tr/haber/kck-ateskesin-bittigini-acikladi- bundan-sonra-tum-barajlar- gerillanin-hedefinde- olacaktir,302608. - Bese Hozat, “Yeni Süreç, Devrimci Halk Savaşı Sürecidir,” Özgür Gündem, (July 14, 2015), retrieved from http://www.ozgur-gundem.com/

yazi/133642/yeni-surec- devrimci-halk-savasi-surecidir . - See footnote 3.

- “Kaç PKK’lı Öldürüldü, Kaç Şehit Verdik? 265 Günlük Bilanço!,” Internet Haber, (March 28, 2016), retrieved from http://www.internethaber.com/

kac-pkkli-olduruldu-kac-sehit- verdik-265-gunluk-bilanco-

1579254h.htm. - Hüseyin Gülerce, “FETÖ’cüler TSK İçinde Kendilerini Nasıl Gizledi?,” Star, (July 19, 2016), retrieved from http://www.star.com.tr/yazar/

fetoculer-tsk-icinde- kendilerini-nasil-gizledi- yazi-1126597/. - The best English language exposé of the Fetullah Gülen cult and its role in the coup in Turkey was published as this article was going into production: Dexter Filkins, “Turkey’s Thirty-Year Coup,” The New Yorker, (October 17, 2016), retrieved from http://www.newyorker.com/

magazine/2016/10/17/turkeys- thirty-year-coup. For a detailed criticism of a stereotypical show trial and the central role of the Gülenists who orchestrated it, see Dani Rodrik, “The Plot against the Generals,” (2014) retrieved from www.sss.ias.edu/files/pdfs/ Rodrik/Commentary/Plot- Against-the-Generals.pdf. - Yıldıray Oğur, “279,889 Kişinin Hakkına Girmek,” Türkiye, (February 3, 2014), retrieved from http://www.turkiyegazetesi.

com.tr/yazarlar/yildiray-ogur/ 578046.aspx. - Yıldıray Oğur, “803 bin 875 Kişinin Hakkına Girmek,” Türkiye, (March 27, 2015), retrieved from http://www.turkiyegazetesi.

com.tr/yazarlar/yildiray-ogur/ 585464.aspx. - Saygı Öztürk, “Telekulaklar Hep Fethullah’a Çalıştı,” Sözcü, (August 10, 2016), retrieved from http://www.sozcu.com.tr/2016/

yazarlar/saygi-ozturk/ telekulaklar-hep-fethullaha- calisti-1346442/. - Soner Yalçın, “Basılmamış Kitabın Yazarını Öldürdüler,” Sözcü, (December 18, 2002), retrieved from http://www.sozcu.com.tr/2014/

yazarlar/soner-yalcin/ basilmamis-kitabin-yazarini- oldurduler-682160/. - “Dink Cinayetinde Gülen Parmağı,” Sabah, (April 5, 2014), retrieved from http://www.sabah.com.tr/

gundem/2014/04/05/dink- cinayetinde-gulen-parmagi. - “Yaver Levent Türkkan İtiraf Etti,” Hürriyet, (July 22, 2016), retrieved from http://www.hurriyet.com.tr/ve-

orgeneral-akarin-yaveri- 40155810. - Dani Rodrik, “Is the U.S. behind Fethullah Gülen?,” (July 30, 2016), retrieved from http://rodrik.typepad.com/

dani_rodriks_weblog/2016/07/ is-the-us-behind-fethullah- gulen.html. - “Hulusi Akar’ı, Fethullah Gülen’le Görüştürmek İstedi,” Habertürk, (July 24, 2016), retrieved from http://www.haberturk.com/

gundem/haber/1271015-hulusi- akari-fethullah-gulenle- gorusturmek-istedi. - Ahmet Zeki Üçok, “O Dönem Hazırladığım Liste Maalesef Bugün Tulum Çıkardı,” Habertürk,

(July 25, 2016), retrieved from http://www.haberturk.com/gundem/haber/1271387-ahmet- zeki-ucok-

o-donem-hazirladigim-liste-maalesef-bugun-tulum-cikardi. - See “Yaver Levent Türkkan İtiraf Etti” and Ahmet Zeki Üçok, “O Dönem Hazırladığım Liste Maalesef Bugün Tulum Çıkardı” in previous footnotes.

- “Mete Yarar’dan Şaşırtan Marmaris Detayı,” Türkiye, (August 5, 2016), retrieved from http://www.turkiyegazetesi.

com.tr/gundem/392105.aspx. - “Coup Facts: Wall of Shame,” retrieved from https://coupfacts.com/wall-of-

shame/. - “FETÖ Darbe Girişiminin Acı Tablosu: 240 Şehit,” Anadolu Ajansı, (July 20, 2016), retrieved from http://aa.com.tr/tr/info/

infografik/1456. - The New York Times, (July 17, 2016), retrieved from https://twitter.com/

nytimesworld/status/

754776778204389376. - On the struggle between Gorbachev and Yeltsin, see George W. Breslauer, Gorbachev and Yeltsin as Leaders, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

- KONDA found that 84 percent of those who participated in the “democracy watch” rallies that were held on a daily basis following the coup attempt in July were likely AK Party voters, and 79.5 percent actually voted for AK Party in the November 2015 elections, whereas 6 percent were too young to vote in 2015. “Demokrasi Nöbeti Araştırması: Meydanların Profili,” KONDA, (July 26, 2016), retrieved from http://konda.com.tr/

demokrasinobeti/. - H. Akin Ünver and Hassan Alassaad, “How Turks Mobilized Against the Coup: The Power of the Mosque and the Hashtag,” Foreign Affairs, (September 14, 2016), retrieved from https://www.foreignaffairs.

com/articles/2016-09-14/how- turks-mobilized-against-coup. - “Erdoğan’s Revenge,” The Economist, (July 23, 2016), retrieved from http://www.economist.com/news/

leaders/21702465-turkeys- president-destroying- democracy-turks-risked-their- lives. - “Es War Einmal Eine Demokratie,” Der Spiegel, (July 27, 2016), retrieved from https://www.amazon.de/SPIEGEL-

30-2016-einmal-Demokratie/dp/ B01E7F8INO. - An increasingly common, disturbing and unfair trend in the West, even among academics, is to discuss Turkey under Erdoğan’s AK Party and Putin’s Russia as being comparably anti-democratic regimes. The last somewhat free, fair, and competitive election Russia had, was arguably the presidential election of March 2000 when Putin was elected for the first time, whereas Turkey has had eleven fiercely competitive national electoral contests since the AK Party came to power in 2002.

- In this context, consider the Democratic Party’s near monopoly over the African American vote, which continues more than fifty years after the Civil Rights Act of 1964. More dramatically, consider the continuing electoral hegemony of the African National Congress (ANC) in South Africa, more than twenty years after the end of Apartheid.

- For my analysis of the coup in Iran, see Şener Aktürk, “Why did the United States Overthrow the Prime Minister of Iran in 1953? A Review Essay on the Historiography of the Archetypical Intervention in the Third World During the Cold War,” The Journal of the Associated Graduates in Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 13, No. 2 (2008), pp. 24-44.

- Şener Aktürk, “The End of the Turkish-American ‘Alliance’ after the Failed Coup?,” TheNewTurkey.

org, (August 8, 2016), retrieved from http://thenewturkey.org//the-end-of-the-turkish-american-

alliance-after-the-failed-coup/.