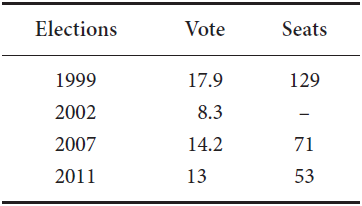

The Nationalist Action Party (Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi, MHP) won 13 percent of the vote in the June 2011 elections, which guaranteed it 52 seats in parliament. Although many parties were registered, the main competition was between the three major Turkish political parties: the AKP,1 the CHP,2 and the MHP. Based on this perspective, the electoral results show a clear defeat of the MHP. Because the CHP, with 26 percent of the vote, doubled the electoral support the MHP was able to garner, while the AKP, the electoral victor, tripled its numbers with almost 50 percent of the vote. Worse, the independent candidates of the Kurdish political movement won 7 percent of the vote, securing 36 seats in parliament. The 2011 election results brought on further frustration for the leadership of Devlet Bahçeli. These results all but branded the MHP as the small party of Turkish politics, and as the party that needed and looked for coalitions without hope of winning an election independently.

Table 1. The MHP’s electoral performance under the leadership of Devlet Bahçeli

As of 2002, Turkish politics turned out to be a four-party game played by the AKP, CHP, MHP, and the Kurdish party.3 Therefore, while analyzing any party’s performance, including that of the MHP, one should recognize the post-2002 period as the main spatial and periodical context, for one major reason: The rise of the AKP as the dominant party has transformed Turkey’s political coalitions. These coalitions should be seen as the “behind-the-scene motors” of Turkish politics. Unlike in the pre-2002 period, the Turkish right is no longer divided. For instance, four out of the five large parties that ran in the 1999 elections and won seats in parliament were rightist parties. In the parliament of 1999, the DSP4 was the only leftist party alongside the four rightist ones. This configuration has one clear message: The rise of the AKP and the purge of the other parties of the Right. This has situated the MHP in a very narrow margin between the Left and Right, or, alternatively it can be viewed as between the state and society. At this point, the MHP is no longer another nationalist rightwing party among other rightist parties, but a party in between the conservative AKP and the secular Kemalist CHP; two parties that stand in sharp contrast to each other. In the pre-2002 period, before the rise of the AKP, the MHP was in a good position to form loose, nebulous coalitions with different sectors of society. That situation no longer exists.

Ever since the 1960s, the MHP has operated with vague party identity that amalgamated different, even contradictory, elements such as Islam, folk nationalism, secularism, militarism, Kemalism, statism, and even Ottomanism. In other words, the MHP was never called upon to display a consistent, exclusive party identity. However, the new parameters of Turkish politics of the post-2002 period have almost terminated the MHP’s former ability to operate with a carefully formulated, obscure party identity. The serious issues that are challenging Turkish politics today, such as civil-military relations, the Ergenekon trial, Islam in the public sphere, the Kurdish question, the crisis of the presidential election and the 2010 referendum, have made a nebulous discourse operationally impossible. The MHP was forced to articulate a very clear stance on each issue. Gradually, the strategy of obscurantism has lost its practicability.

However, the MHP faced a similar crisis in the past. For instance, in the late 1990s, when the military brought down the Welfare Party (RP), Turkish political positions polarized. And a bipolar political climate emerged between the Islamic RP and the ultra-secular army, which was in alliance with other Kemalist actors, including the media, the higher courts and the bureaucracy. Indeed, the Turkish political system was already experiencing a sharpening of power relations. In that climate, the MHP was successful at creating an image of itself as the less confrontational party.5

This polarization, paradoxically, has weakened the traditional MHP position that its calculatedly obscurantist discourse had secured for it

The sharpening of power relations in the post-2002 period is different in two ways. First, the other right wing parties have faded away, and the MHP found itself alone in the stand off between the conservative AKP and the Kemalist CHP. Second, unlike in the past, the AKP-led political coalitions, now including the Gülen Movement, have come up with powerful reformist demands, such as the termination of the traditional Kemalist-elitist structure of the high courts, and the arrest by the civilian courts of a number of generals. In effect, the new conservative actors’ main strategy is to defeat the traditional Kemalist coalitions and state bureaucracy, and thereby incorporate the state into their jurisdiction. Thus, compared with the demands of the former rightist politicians such as Menderes, Özal, Demirel or Erbakan, the demands of the new conservative actors are more reformist, intent on the re-organization of the state apparatus as a whole. A telling difference in the political clout of these new actors and that of the pre-2002 right wing leaders is in that the latter were not able even to appoint a chief to the National Intelligence Service (Milli İstihbarat Teşkilatı, MIT), nor to re-shape the Council of Higher Education (Yüksek Öğretim Kurulu, YÖK).

Unlike the AKP’s, all previous rightist politicians’ main strategy was to partially achieve their aims through endless bargains in which they held the weak end of the bargaining stick, while the Kemalist state apparatus held the dominant one.6 In obvious contrast, the AKP government has the unprecedented capacity to appoint or dismiss the incumbents of the highest posts in the state apparatus, including the army generals. Thus, the assertive position of the new conservative actors has polarized the political environment such that the significant actors are on the one hand, the reformist conservatives and on the other, the Kemalists who are resisting any change. This polarization, paradoxically, has weakened the traditional MHP position that its calculatedly obscurantist discourse had secured for it.

The origin of the MHP’s deliberate obscurantism lies with the fact that Türkeş was among the members of the junta that led the 1960 coup that ended in the execution of Menderes

This paper argues that the recent polarization put an end to the MHP’s strategy and discourse of traditional obscurantism, causing in these last elections this party’s unimpressive electoral performance.

The Origin of the MHP’s Obscurantism: The 1960 Junta and Alpaslan Türkeş

Alpaslan Türkeş, a former colonel and member of the junta that led the coup of May 27, 1960, was the founder and the main ideologue of the MHP. The 1960 coup was the first military intervention in the Republican period. The military’s main strategy was to emerge as the guardian of the Republic, and to reestablish the Kemalist status quo. The Kemalist elites were of the opinion that the ten-years rule of Democrat Party (DP) was reactionary, and thus incompatible with the Kemalist vision of secularism. The Kemalist elites considered dangerous the new political coalitions that had emerged during the DP period. Thus, as Karabelious notes, the 1960 intervention was the reaction of the state elites to the “unhealthy” autonomy culled out by economic and political groups at the expense of the Kemalist contract, mainly during the rule of the Democrat Party between 1950 and 1960.7 However, more important is the 1960 coup’s legacy, and the symbolic set of meanings it produced that survive to the present day.

The 1960 coup created the most effective political fault line in Turkish politics. It drew the historico-pyschological line between Kemalism and the conservative, mainly Islamic, masses. On the one hand, for the Kemalists, the 1960 coup was the “revolution” that had protected the secular characteristics of the regime. For conservatives, on the other hand, it was an abominable event. Thus, the typical Kemalist elite praises the 1960 coup, while the typical conservative elite sees it as another example of Kemalist authoritarianism. Since then, Adnan Menderes, the former leader of the DP who was executed after the coup, became the symbol of the conservative masses’ opposition to Kemalism. All conservative and center-right parties have claimed to be the heirs of the DP.8 Similarly, all religious groups, including Naqshbandiyyah, Nurcu, and the Gülen Movement,9 have declared Menderes a martyr. Despite his secular background, Menderes was declared an İslam kahramanı (hero of Islam) by Said Nursi.10 The 1960 coup and the execution of Menderes is the “point of departure” of any political debate since then. Even as late as 2007, the AKP copied the DP’s electoral motto of the 1950 elections. Big posters picturing Erdoğan with Menderes decorated the major crossroads of big cities during the election campaign.

Türkeş’s balancing of communitarian values and statist nationalist ideology was aimed at a reconciliation between the Kemalist state and the Muslim people

The origin of the MHP’s deliberate obscurantism lies with the fact that Türkeş was among the members of the junta that led the 1960 coup that ended in the execution of Menderes. In other words, Türkeş was a key actor of a process that was later condemned by large sectors of the Turkish right as an immoral and detrimental event. Türkeş’s later efforts to keep his party independent of vehement split between the conservatives and Kemalists is the historical origin of the MHP style of obscurantism. Although Türkeş was himself part of the junta, he worked painstakingly at distancing himself from it.

Touting a nationalist agenda, Türkeş understood that he was in need of a popular discourse that would enable him to make contact with the masses. Moreover, as he would soon declare communism the major enemy, he had developed a need for religion to articulate his mission successfully. Also, there was a natural tension in his pursuit of a popular nationalist agenda and his having been a member of the 1960 junta that had justified itself as the protector of Kemalism. All this forced Türkeş into reliance on an obscurantist strategy.

Seven months after the coup of May 27, 1960, fourteen members of the junta, including Türkeş, were sent into exile by its other members. Among the junta membership, Türkeş was the prominent defendant of the long military rule in Turkey, thus apparently the leader of the “radicals.”11 Supporters of a quick return to civilian rule purged the group affiliated with Türkeş. Marginalized by the present Kemalist army elites, and by then a former colonel, Türkeş had no chance of pursuing his agenda within the Kemalist structure. His only option was to formulate a new political strategy that would give him strength in the political arena. Yet Türkeş’s political ideas traced back to his service in the junta. Unlike the pro-CHP junta members who were mainly under the political influence of the CHP’s leader, İsmet İnönü, Türkeş was in contact with Turkist intellectuals such as Nihal Atsız, and even with some former members of the DP, the party that had been closed down by the junta.12 Though he had been a member of a Kemalist junta, Türkeş was aware of the limitations of the Kemalist state’s efforts to create any significant degree of social legitimacy.

This backdrop and the above-listed tensions in Türkeş’s personal circumstances dictated the obscurantist requirement. It materialized as his famous Dokuz Işık Doktrini (Nine Lights Doctrine), a clear realization of the obscurantist approach. Türkeş delivered his message, the “third way,” as an alternative to capitalism and communism. He believes that his doctrine is the successful merger of Turkish communitarian values and statist nationalist ideology,13 opining that he has devised a system particularly appropriate for the Turkish nation, one that is different from the class-centered concerns of communism and the individual-centered concerns of capitalism.14

In practice, the MHP comes under pressure to express a new position in the state-society continuum

In fact, Türkeş’s balancing of communitarian values and statist nationalist ideology was aimed at a reconciliation between the Kemalist state and the Muslim people. Unlike the CHP, Türkeş calculated that such a moderate way could generate a functional corridor between the state and society. To realize this, Türkeş’s communitarian values recognize and incorporate popular concepts such as Islam. In other words, Türkeş’s main strategy was to reconcile the Kemalist state with the popular values of Turkish people, including religious ones. However, unlike other Islamic or conservative parties, Türkeş’s MHP has never been critical of the major attributes of the Kemalist regime. More precisely, Türkeş was a Kemalist officer. As Landau notes, Kemalism has always guided the MHP.15

Political obscurantism is the strategy of formulating a vague discourse when political actors believe a clear and transparent discourse is not in their interest. Actors may employ this strategy either to minimize a risk or maximize an interest. Political obscurantism can be observed in many societies, but it is more prevalent in authoritarian ones.16 Political obscurantism has been an important strategy of Turkish politics, so the MHP is not the only party that can be analyzed under this lens. For instance, religious actors used the obscurantist discourse to address secularism, or Atatürk, to avert potential pressure from the Kemalist bureaucracy of the past. The MHP brand of obscurantism, which was drafted by Türkeş, aimed at creating a popular nationalist party that attracts the interest of the large conservative Anatolian masses but retains the Kemalist paradigm.

This strategy required the careful balancing of state and society by the MHP. Its standard Kemalist propositions developed a populist discourse that sought better harmony with religion and culture. The aim was to generate a new discourse on major issues such as religion, secularism, and the state, a discourse that is more in tune with the popular culture of the large Anatolian masses. For this brand of discourse, secularism is the synthesis of rural cultural motifs. It is open even to religious motifs. But it posits the state as an ontological necessity of the survival of the nation.17

The MHP entered the election campaign under heavy pressure from the conservative block to take a clear anti-Kemalist stance

Expounding upon the state, the MHP’s discourse washes it together with religion, as the latter also consecrates the state as a main instrument of religion.18 The MHP’s obscurantist discourse was indeed very practical for a long time. However, the transformation of Turkish politics, particularly since the early 2000s, has made this strategy ineffective. Two major reasons can be cited for this. First, as a result of political conflicts and the development of the democratization process, which has increased the level of transparency in Turkish politics, actors and their discourses are more open today than they were twenty years ago. Second, the major issues that dominate Turkish politics have also made obscurantism obsolete. Actors are expected to clarify their position on very straightforward questions, such as whether they endorse the headscarf or Kurdish-language TV channels. Consequently, the general parameters of Turkish politics force political actors to display a manifest position on such issues.

In practice, the MHP comes under pressure to express a new position in the state-society continuum. For instance, as early as 2000, Hüseyin Gülerce, a columnist of the leading conservative newspaper, Zaman, wrote that the MHP should declare its positions on several major issues such as the Ergenekon trial or the status of the army in politics.19 Since then, similar demands have repeatedly come from both conservative and secular groups. The extreme polarization of conservatives and Kemalists pressured the MHP to declare its position vis-à-vis each group. Its compliance with that advice was, however, not an unqualified success. For instance, the MHP’s siding with the CHP against the AKP during the constitutional referendum of 2010 was called “political suicide” by conservative groups.20 Major conservative newspapers, such as Zaman and Yenişafak, published innumerable comments warning the MHP that cooperation with the Kemalist CHP would work to its detriment.

The Election Campaign of 2011: Strategies and Discourses

The MHP entered the election campaign under heavy pressure from the conservative block to take a clear anti-Kemalist stance. Despite such difficulties, the MHP began its campaign with an upgraded obscurantist discourse in which it came out with a selective reading of the major issues of Turkish politics. The party’s early calculation was that maintaining the traditional obscurant discourse would pay off. But from the very beginning of the campaign, this caused doubts on whether the present MHP leadership would manage its state- society balance successfully.

The Political Landscape: Rivals and Enemies

The MHP designed its electoral strategy mainly in terms of knee-jerk opposition to the ruling AKP. The party’s anti-AKP strategy focused on several key topics. First, the AKP was criticized for causing the disintegration of Turkey’s unity. Accusing the AKP of bölücülük (separatist inclination) was the main thrust of Bahçeli’s electoral agenda. At the Sivas meeting, Bahçeli charged the AKP with being “separatist on an ethnic basis” (etnik temelde bölücü), which, it should be noted, is a very harsh charge by Turkish standards.21 He also accused the AKP of tolerating Kurdish separatism to the extent that it has become an accomplice of the PKK. Secondly, the MHP blamed the AKP for the weakening of the nationalistic or Turkic characteristic of Turkey. With this essentialist argument, the MHP is claiming that the AKP’s economic and social policies are destroying the traditional and national character of the Turkish nation. Thus, Bahçeli promised a “restoration government” after the elections.22 Finally, the AKP came under the MHP’s criticism for corruption, especially for creating a new class of rich people by means of its system of political protection.

Faced with this challenge, the MHP moved to mount an ideological assault on the AKP, by leveling the accusation that the AKP has nurtured threats to national unity

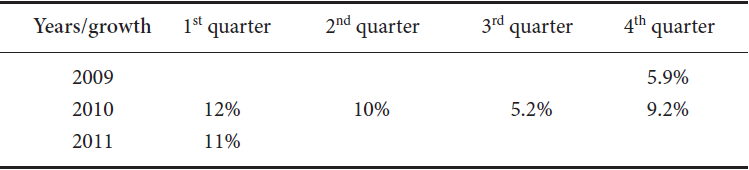

A major handicap for the MHP strategy was the AKP’s concrete successes in various fields, such as in the housing sector and health services. Moreover, since it was founded, the AKP has had successive electoral victories. Part of this electoral success is linked to the AKP’s successful management of the economy. Two academics, who analyzed economic performance and political outcomes in Turkey between 1950 and 2004, demonstrated that “Turkish voters [are found] to take government’s economic performance into account, but they do not look back beyond one year.”23 Based on this premise, the economic performance of the AKP government (see Table 2), especially in the period preceding the elections of 2011, was very successful.

Table 2. The growth of the Turkish economy before the 2011 elections

With this strong track record of economic growth, the AKP government built its electoral strategy mainly on the marketing of political and economic stability and development. Faced with this challenge, the MHP moved to mount an ideological assault on the AKP, by leveling the accusation that the AKP has nurtured threats to national unity. Despite launching this assault, the MHP did not develop an independent discourse on the Kurdish issue during the electoral campaign. Instead, it approached the Kurdish problem (or the “terror problem,” as the MHP calls it) as a part of its anti-AKP strategy. The reading it had was that the PKK problem is the result of the AKP’s misguided policies. In other words, the MHP’s anti-PKK campaign in fact targeted the AKP. For instance, in his Diyarbakır (the central city of Kurdish population and politics) meeting, Bahçeli accused the AKP of having the same ‘dangerous targets’ as the PKK.24 Even a general perusal of Bahçeli’s election speech reveals that he accused the AKP of being the main source and cause of the problems that dog the Kurdish question.

It was not surprising that these events ‘traumatized’ the MHP administration, which viewed the AKP as an “enemy,” to the extent that the MHP believes that the AKP is trying to eliminate it as a political competitor

So, why did the MHP target the AKP on such a scale? Conservative actors, including the AKP, were correctly aware of the fact that the MHP was tightly wedged between the Kemalist state and the reformist conservatives. The very impracticability of the old obscurantist strategy that masked its author’s stand vis-à-vis the state and society became a tactical advantage for the AKP. Tayyip Erdoğan made a major point of criticizing the MHP’s failure to hear the demands of conservative people. Similarly, he accused the MHP of cooperating with the supporters of the Kemalist state, and openly courted the nationalist vote, with the charge that “the MHP is no longer a genuine nationalist party.”25 He also kept sending direct messages to the Ülkücü (literally, “the idealists,” which is the common descriptor of the nationalist activists who share the MHP’s ideology). At all major meetings, Erdoğan reserved some time for communicating with the Ülkücü voters. As part of this campaign, Erdoğan met several key former nationalist leaders, and even nominated one of Alpaslan Türkeş’s sons as a candidate from his party’s list. Meanwhile, the mayors of several cities, who had been elected as MHP candidates, resigned from their party to protest it. Vedat Bilgin, a chief advisor to Devlet Bahçeli, resigned from his post, and re-imagined himself into a pro-AKP politician. It was not surprising that these events ‘traumatized’ the MHP administration, which viewed the AKP as an “enemy,” to the extent that the MHP believes that the AKP is trying to eliminate it as a political competitor.

Meanwhile, compromising tapes of a sexual nature, involving some members of the MHP, were leaked just before the elections. This development provoked the resignations of ten of the top party executives. The MHP quickly blamed the AKP for the leak. Moreover, the tapes event consolidated the sharp tensions and acute competition between the MHP and the AKP, so much so that the MHP reverted to survival mode, with Ali Torlak, an MHP member of parliament, publicly charging the AKP with nefarious intent. His statement is still on the official homepage of the Istanbul branch of the MHP. Torlak’s statement is very clear: “The ultimate goal of the AKP’s leadership is to disintegrate and annihilate the MHP, the only party that can stop it!”26

The competition between the AKP and the MHP did not pan out as the typical electoral campaign that centers on the various solutions for Turkey’s problems. Instead, it was a political battle, in which each side is bent on the annihilation of the other. However, this was not a game played exclusively by these two actors, as a third actor, the Gülen Movement, although not organized as a political party, also played a key role in it.

Behind the political scene, the social dynamics that transformed the MHP’s view of the Gülen Movement are more complex

The Gülen Movement is commonly described as “the largest Islamic movement in Turkey and the most widely recognized and effective one internationally.”27 Being such a global phenomenon, the Movement is very influential in different fields, including the media. The most critical power of the Movement is in its capacity for the en masse mobilizing of youth groups. Briefly, the Movement can be seen as the new social modus of the young conservative Anatolians, whether they are students or entrepreneurs. Normally, the MHP is very careful in its interactions with the Movement. None of its members had ever criticized Gülen or his followers. Gülen used to have very strong personal ties with Alpaslan Türkeş, who had praised the Movement several times for its activities, especially for those in the Central Asian Turkic states. Back in 1997, Türkeş wrote a letter to Gülen that openly expressed his appreciation for this Movement’s activities among Turkic people.28

However, the MHP and the Gülen Movement adopted completely different political positions on major issues after 2000. The Gülen Movement demanded a clearer anti-Kemalist stance from the MHP. This was never delivered. When the Ergenekon trial broke, in the course of which many military officers including generals were arrested, the MHP followed a political path that was totally different from that of the Movement. Whereas the Gülen Movement became an ardent defender of the Ergenekon trial, the MHP deemed it a dangerous challenge to state order. For Bahçeli, the Ergenekon trial was a planned action to weaken the Turkish army.29 Moreover, the MHP even nominated a former general, who was arrested as a consequence of the Ergenekon trial, as its parliamentary candidate in the 2011 elections. In this context, Bahçeli did not refrain from criticizing the Gülen Movement during his election campaign. This was a novel event in Turkish politics. This political calculation transformed the MHP and the Gülen Movement into indirect competitors in the 2011 elections.

However, behind the political scene, the social dynamics that transformed the MHP’s view of the Gülen Movement are more complex. In retrospect, it is evident that the MHP’s social constituencies were Anatolian towns and villages, particularly in middle and eastern Anatolia. There, the MHP held a monopoly on the offer of social mobilization opportunities for young people. People who are critical of the Kemalist CHP and of Islamist politics used to see the MHP as the third way. However, the rise of the Gülen Movement in Anatolian towns virtually ended the MHP’s historical monopoly. Even in Anatolian cities, such as Yozgat and Çankırı, known in the past as MHP strongholds, the party was marginalized. The weakened MHP position in these areas reduced the MHP’s recruitment ground and financial support.

The MHP’s approach to the Ergenekon case and the party’s position during the 2010 referendum coerced the Gülen Movement into closer alignment with the AKP

Another critical challenge posed by the Gülen Movement came from Turks living outside of Turkey, mainly in the newly created Central Asian Turkic states. In Turkish politics, the MHP had almost monopolized the issue of Turks or Turkic people living outside of Turkey’s borders during the Cold War era. However, the Gülen Movement challenged this monopoly in the 1990s. Organized in many countries and regions and having established its own schools, the Movement deserves to be recognized as a successful actor in the creation of transnational spaces. As part of its agenda, the Movement has opened many schools and universities in Kazakhstan, Crimea, Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, and Turkmenistan, and even in Northern Iraq. In short, the social potential in Turkey to create transnational spaces for the Turks living outside of Turkey was taken over by the Gülen Movement, which reduced the traditional role of the MHP.

Meanwhile, the MHP’s approach to the Ergenekon case and the party’s position during the 2010 referendum coerced the Gülen Movement into closer alignment with the AKP. A somewhat ambiguous but pragmatic coalition emerged between the Gülen Movement and the AKP. In fact, the Gülen Movement and the AKP have different Islamic backgrounds, and they differ on many major issues. For instance, Fethullah Gülen publicly criticized the Mavi Marmara incident, which they considered to be a major interference by the AKP government.30 Even so, the polarization of Turkish politics made the AKP’s position acceptable to the Gülen Movement.

Naturally, the situation outlined above affected the MHP’s electoral campaign structurally. The MHP categorized its competitors, placing parties like the CHP into its “political competitors” slot, and the Gülen Movement and the AKP into the “bent on annihilating the MHP” slot. This strategy created the two major setbacks for the party, which explained its failure in the elections. First, the MHP’s open clash with a religious social movement weakened its image among the large conservative masses. Second, the same strategy produced the impression that the MHP sided with the CHP, the Kemalist party. Analyzing the election results, it is very apparent that religious and conservative electors did not endorse the MHP’s political position.

Realizing that many people were disillusioned with the RP, the MHP purposely distanced itself from Islam to present itself as a pro-system mainstream party

It should be noted also that this MHP predicament had occurred before in the 1990s, when the party re-defined its relations with Islam. Since communism was “the other” for nationalist thought during the Cold War, Islam was used as a means to consolidate the nationalist movement. The collapse of Soviet communism persuaded the Türkeş-led MHP to redefine its position on Islam. Admittedly, the malevolent relationship between the Kemalist establishment and the Islamist movement encouraged the MHP’s maneuvers in this matter. Actually, the tension between the RP-led government and the military in the 1990s, and the consequent collapse of the government under military pressure, was read carefully by the MHP elites. Realizing that many people were disillusioned with the RP, the MHP purposely distanced itself from Islam to present itself as a pro-system mainstream party.31

Two Structural Deficits

Apart from the competition between the MHP and other political actors, two independent structural deficits should be analyzed to explain why the MHP failed in the recent elections. Pragmatically, these two deficits reduced the MHP’s capacity for reaching a wide range of voters. A brief analysis of these two structural deficits follows.

Poor Ties with the Business Community

Compared with, for example, the Islamists, the MHP has a poor record of creating ties with Turkey’s business community. Some limited exceptions aside, such as the failed attempt to create the Nationalist Businessmen Association,32 the MHP has made few efforts to forge good relations with established business circles. It has not founded any organization like MÜSİAD, the federation known for its organic links with the Islamic parties. Naturally, without such institutions, the MHP cannot transmit its message to large masses. Indeed, business organizations such as MÜSİAD and TUSCON (the businessmen’s federation known for its close contact with the Gülen community) encourage political activity through economic channels. The role of such organizations in teaching and advocating the Islamists’ more globalist vision should be noted.33 The failure to form such organizations keeps the MHP in a kind of closed system that lacks the necessary intermediaries to carry its agenda to voters. Remaining “cut off” in this sense, the MHP fails to heed a well-known political tenet on the nature of political party identity: “We define the identity of a political party as the image that citizens have in mind when they think about that party. Political parties develop their identities through the different faces they present to the public while in and out of government.”34

The absence of intermediaries had a heavily negative effect on the MHP’s electoral performance

Lacking the tools of identity construction, the MHP comes over as an ideological institution without any connections to the people. This party follows a model that expects true partisanship from its supporters. When political parties can attract the electoral support of the masses through the agency of intermediaries, there is no need in this exercise to ask for ideological loyalty. Thus, the absence of intermediaries had a heavily negative effect on the MHP’s electoral performance.

An Essentialist Election Manifesto

According to saliency theory, parties try to render selective emphases by devoting the bulk of their attention to the types of issues that favor themselves, and by paying correspondingly less attention to issues that favor their opponents.35 Upon analysis of the MHP’s election manifesto, it becomes very clear that its entire text is essentialist, disdaining to put emphasis on its proposed solutions of the major problems of Turkish politics. Admittedly, the manifesto includes many remarks about the MHP’s solutions in the fields of education and the economic and rural sectors. But the general spirit of the manifesto engages only tangentially with practical problems and their solutions, focusing instead on conceptual problems, most particularly with the survival of the Turkish state in its united form. For instance, the manifesto (Seçim Beyannamesi) begins with a very strong analysis of the threats posed by the current developments in the Turkish state and nation:

Global sovereign powers employ civil-society organizations, and ethnic and religious entities in order to realize their goals. The nation state is under threat, and the castles of national resistance are challenged, just as they are in other states targeted by the global powers. The MHP is fully aware of how these developments threaten Turkey.36

In other words, careful analysis reveals that the election manifesto prioritizes ontological threats to the Turkish state, engaging only half-heartedly with the daily problems of citizens, such as unemployment or transportation. Thus, the over-arching impression the reader gains is that day-to-day problems are secondary issues in the party’s estimate of where its most important duty lies: in the struggle for the survival of the Turkish state and nation. But in the present climate, an essentialist manifesto that calls upon the public to fight the enemies of Turkish unity tends to leave voters cold. The ordinary voter supports a political party and demands solutions for his/her daily problems in the economic sector, the transport sector, and the cost-of-food sector.37 As a result, attributable to the tenor of its manifesto, the MHP secured high electoral support only in cities such as Manisa or Mersin, where tension between Turks and Kurds has been exacerbated by the recent Kurdish immigration to these cities from eastern Turkey. In other words, its essentialist strategy confined the MHP to the security-politics cage, and was only appealing to voters where the Kurdish problem is an issue in the voters’ daily lives.

The Turkish state, engaging only half-heartedly with the daily problems of citizens, such as unemployment or transportation

Conclusion

Recent developments in Turkish politics eliminated the viability of the MHP’s traditional obscurantist party strategy. Equally, they have reduced the party’s traditional field of maneuver. The harsh polarization of the Kemalist-establishment/CHP bloc and the peripheral conservatives (the AKP and the Gülen Movement) debilitated the MHP’s capacity to put forward a “third way” for voters. The two referendums (2007 and 2010) consolidated the polarization of the Turkish electoral configuration, with the Kemalists in one bloc and the new conservative actors in the other. The MHP was left out on a limb, as this anti-PKK party was unable to attract the support of the masses. The people, who were worried about the PKK threat and the disintegration of the Turkish state, became the natural but narrow political base and constituency of the MHP.

The future performance of the MHP will be determined mainly by how the party re-defines its position on the state-and-society equilibrium. Since its traditional obscurantist strategy is no longer viable, the MHP must develop a major new policy. That is no easy task, as it requires assuming new political positions on several big issues, such as the free market, globalization, and the rise of Islam in the Turkish public space. Of equally critical importance is whether the current leadership of the party can carry out a reformist agenda, or whether the party is facing an imminent internal power struggle.

Endnotes

- Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi/The Justice and Development Party.

- Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi/The Republican People’s Party.

- The latter is organized under various titles and formations.

- Demokratik Sol Parti/Democratic Left Party.

- Bulent Aras and Gökhan Bacık, “The Nationalist Action Party and Turkish Politics,” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, Vol.6, No.4, (Winter 2000), p. 52.

- Gökhan Bacık and Sammas Salur, “Coup Proofing in Turkey,” European Journal of Economic and Political Studies, Vol.3, No.2, (2010), p. 169.

- Gerassimos Karabelios, “The Evolution of Civil-Military Relations in Post-War Turkey, 1980-95,” Middle Eastern Studies, Vol.35, No.4, (October 1999), p. 141.

- Sedef Bulut, “27 Mayıs 1960’tan Günümüze Paylaşılamayan Demokrat Parti Mirası,” SDÜ Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, No.19, (May 2009), p.73.

- May 27, 1960 coup was described as the “first strike to democracy” as indicated on Fethullah Gülen’s official homepage. Also in a related interview Gülen said, “I never digested the coup. My inner tension continued for a long time.” http://tr.fGülen.com/content/

view/9971/13/ - Said Nursi, Emirdağ Lahikası (İstanbul: Sözler, 2009), p. 592. Also available at: http://risale-inur.org/

yenisite/moduller/risale/ index.php?tid=161 - Ümit Özdağ, Menderes Döneminde Ordu-Siyaset İlişkileri ve 27 Mayıs İhtilali (İstanbul: Boyut, 2004), p. 339.

- İbid., p. 340,

- Alpaslan Türkeş, Milli Doktrin Dokuş Işık (İstanbul: Hamle, 1978), p. 15.

- Filiz Başkan, “Globalization and Nationalism: The Nationalist Action Party of Turkey,” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, Vol.12, No.1, (Spring 2006), p. 91.

- Jacob M. Landau, Türkiye’de Sağ ve Sol Akımlar (Ankara: Turhan, 1979), p. 312.

- Political environment tremendously affects party behavior. On this, see: Benjamin Reilly and Per Nordlund, Political Parties in Conflict-Prone Societies: Regulation, Engineering and Democratic Development (Tokyo: UN University Press, 2008).

- Gökhan Bacık, “The Fragmentation of Turkey’s Secularists,” Turkish Review (January/February 2011), pp. 16-17.

- It should be pointed out that in Turkey, all major interpretations of Islam, ranging from that of the Islamist camp to those of the apolitical Nurcu movements, recognize the state as a necessity to the point that they label it “sacred.” The fusion of state and nationalism is a recurring theme of the various political actors in Turkey, whether they are nationalist or religious. Cemal Karakas, Turkey: Islam and Laicism between the Interests of State, Politics and Society (Frankfurt: Peace Research Institute, 2007), p.8.

- Hüseyin Gülerce, “MHP Kongresi,” Zaman, November 2, 2000.

- “MHP’nin Siyasi intiharı,” Bugün, September 20, 2010.

- “Başbakan bölücü ve ayrımcı,” Yeniçağ, June 3, 2011.

- “Kim Bu AKP Damgalı Zenginler?” Gazete5, http://www.gazete5.com/haber/

devlet-bahceli-malatya-miting- konusmasi-5-haziran-2011- 114969.htm - Ali Akarca and Aysit Tansel, “Economic Performance and Political Outcomes: An Analysis of the Turkish Parliamentary and Local Election Results Between 1950 and 2004,” Public Choice, Vol.129, No.1-2, (October 2006), pp. 77-105.

- Milliyet, June 6, 2011.

- Star, September 7, 2010.

- http://www.mhpistanbul.org.tr/

node/339 (September 7, 2011). - Berna Turam, “The politics of engagement between Islam and the secular state: ambivalences of civil society,” The British Journal of Sociology, Vol.55, No.2, (2004), p. 265.

- Zaman, August 15, 2000.

- Milliyet, January 14, 2009.

- The Wall Street Journal, June 4, 2010.

- Başkan, “Globalization and Nationalism,” p. 93.

- Milliyetçi İşadamları Derneği.

- Ziya Öniş, “Conservative Globalism at the Crossroads: The Justice and Development Party and the Thorny Path to Democratic Consolidation in Turkey,” Mediterranean Politics, Vol.14, No.1, (2009), p. 22.

- Kenneth Janda, Robert Harmel, Christine Edens and Patricia Goff, “Changes in Party Identity: Evidence from Party Manifestos,” Party Politics, Vol.1, No.2, (1995), p. 171.

- Paul Pennings and Hans Keman, “Towards a New Methodology of Estimating Party Policy Positions,” Quality & Quantity No.36, (2002), p. 56.

- MHP, Seçim Beyannamesi (Ankara, 2011), p. 2.

- Gökhan Bacık, “MHP Ne Vaat Ediyor?” Zaman, April 28, 2011.