Introduction

The Mediterranean Sea is a narrow enclosed sea requiring the coastal states to draw maritime boundaries to separate their respective continental shelves and Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ). The Eastern Mediterranean Sea is currently the most contested section. The coastal States have conflicting views concerning the possible courses of the maritime borders. Alongside the disagreements over the delimited areas, the established boundaries through bilateral agreements have not secured the endorsement of all the related sides. These maritime boundary disputes cause the political tension to flare-up whenever one side or more conduct energy-related activities. In almost every instance, a coastal State has contested the act of the other bringing the whole situation to a point of near military confrontation.

Maritime delimitation is a difficult process if islands are involved. Parties do not easily agree on the size of the maritime areas to be accorded to islands. In fact, islands have been at the core of the disagreements in all the maritime delimitation disputes. The related states are left with no choice but to take the disputes to international courts for settlement. Other geographical features such as the geographical location of the coasts of the related States and their respective coastal lengths create relatively less complicated situations.1

Regardless of its surrounding political circumstances, the Eastern Mediterranean is a difficult region for maritime delimitation basically due to the presence of islands, namely the island of Cyprus and Greek islands of Crete (Girit), Kasos (Çoban Adası), Karpathos (Kerpe), Rhodes (Rodos) and Kastellorizo (Meis).

The legal arguments of the States in the region over this rather technical matter carry therefore a significant value if the settlement is to be sought through international law. This review focuses on the legal approach of Turkey without a detailed evaluation. The aim here is rather to identify both the claims of Turkey over the maritime borders and to review legal arguments to clarify the fundamental points of this approach.

The Developments over the Maritime Areas in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea

Despite its frequent use, the geographical limits of “the Eastern Mediterranean Sea” do not have a comprehensive agreement.2 This is not however a matter to settle here as far as maritime delimitation is concerned. Disputing parties or competent courts should not bind themselves with such a definition but rather with the coastal projections that “meet and overlap” in a delimitation process.3 It is however clear which countries are involved in the issue of maritime delimitation in the region. The states which are actually and potentially affected by maritime delimitation in the region are Turkey, Egypt, Greece, Israel, Palestine, Libya, Lebanon, Syria, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), and the Greek Administration of Southern Cyprus (GASC).

The very first disagreement over the establishment of maritime boundaries emerged when a delimitation treaty was signed between the GASC and Egypt on February 17, 2003

Six countries, namely Israel, Lebanon, Syria, Libya, Egypt, and the GASC have declared EEZ.4 Since there is no need for declaration, other states, including Turkey, have continental shelf areas. Some states have chosen to sign an EEZ Delimitation Agreement without a declaration.5 EEZ is part of the memorandum that Turkey signed with Libya on November 17, 2019. Therefore, Turkey does apply an EEZ in the Eastern Mediterranean, at least in relation to Libya.

The very first disagreement over the establishment of maritime boundaries emerged when a delimitation treaty was signed between the GASC and Egypt on February 17, 2003.6 Turkey made an immediate formal objection to the treaty arguing that it infringed on its possible continental shelf areas.7 It was also argued that the GASC acted illegitimately by ignoring the Turkish side of the island of Cyprus.8 The exploration licenses, which were based on this disputed treaty,9 also provoked objections and preventive measures from Turkey.10

Despite these objections, the GASC continued to sign similar treaties. It signed a delimitation treaty with Lebanon on January 17, 2007,11 and later with Israel on December 17, 2010. The TRNC has officially objected to these treaties on the grounds that the GASC was not the sole legal representative of the whole island and that it, therefore, violated the continental shelf rights of the TRNC.12 Lebanon also objected to the treaty between the GASC and Israel arguing that it violated its own area in the adjacent section between the two countries.13

Following all these delimitation treaties, Turkey did not only raise official objections but also took some practical measures by conducting exploration activities and taking preventive measures against the foreign ships licensed by the GASC. Not surprisingly, the GASC too frequently raised objections to the Turkish acts.14 Moreover, Turkey signed a Continental Shelf Delimitation Agreement with the TRNC on September 21, 2011 and established the continental shelf boundary between the two sides in the North of the Island.15 Based on the treaty, the Government of the TRNC issued exploration licenses to the Turkish Petroleum Corporation (TPAO) covering both the North and South of the Island.16

A similar but more recent step by Turkey is the Delimitation Agreement with Libya. Following the negotiations between the Turkish President and the Chairman of the Presidential Council of Libya, Turkey signed the “Memorandum of Understanding on the Delimitation of Maritime Jurisdictions in the Mediterranean Sea” on November 27, 2019, with the Libyan Government of National Accord. The agreement established the continental shelf and the EEZ maritime boundary between the two countries, shown on a map attached to the Memorandum.17 The treaty came into effect on December 8, 2019.18 There are objections to this agreement by Greece,19 Egypt,20 and Syria.21 They argue that the agreement is null and void as “it has not been ratified by the Libyan Parliament.” The EU appears to be unhappy with the agreement as well.22

Turkey, claims that the boundary between Turkish and Egyptian coasts should be a median line, leaving the western part to be decided with an agreement among all related states

As the final development in the series of disputed maritime delimitation treaties, Greece and Egypt signed an EEZ Delimitation Agreement on August 6, 2020, also covering the area previously delimited by Turkey and Libya. Turkey declared this agreement null and void, as it “violated the continental shelf/EEZ areas of both Turkey and Libya.”23 This brief account of developments clearly demonstrates that the above-mentioned treaties have not resolved the existing disputes but rather created new ones. The disputed maritime treaties, as well as the un-delimited areas, still constitute the core of the maritime disputes in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea.

Turkey’s Claims on Maritime Jurisdictional Areas in the Eastern Mediterranean

Turkey has gradually clarified the extent of its claimed areas through official communications, the concessions were given to the TPAO, and bilateral delimitation agreements. In an official letter, Turkey made it quite clear that the areas falling beyond the western part of the longitude 32016’18’’ are ibso facto and ab initio the Turkish continental shelf or EEZ.24 Turkey, therefore, considered all areas beyond the territorial waters of the GASC to the West of the Island as the continental shelf or EEZ of Turkey.25

This claim was further confirmed in the petroleum concessions given by Turkey to the TPAO to the West of the island of Cyprus. The concessions given on April 27, 2012 in the area of No: XVI covered the West of the island of Cyprus beyond the longitude 32º16’18” E up to a certain line.26 Similar concessions were given to the TPAO to the West of the island of Cyprus in both 2007 and 2008.

Concerning the area between Turkey and Egypt, on the other hand, Turkey requested the boundary to “follow the median line between the Turkish and Egyptian coastline, the western terminal point of which will be determined in accordance with the outcome of the future agreement in the Aegean Sea as well as the Mediterranean among all concerned States, taking into account all relevant and special circumstances.”27 Turkey, therefore, claims that the boundary between Turkish and Egyptian coasts should be a median line, leaving the western part to be decided with an agreement among all related states.28

The most controversial section of the delimitation area in the region is currently the area between the Turkish coastline and Greece. Contrary to the Greek stance to give full effect to all Greek islands including the tiny island of Kastellorizo, the boundary that Turkey claims as equitable in this part do not allow maritime areas to the Greek islands beyond their territorial waters.29 This is the core of the dispute between the two sides.

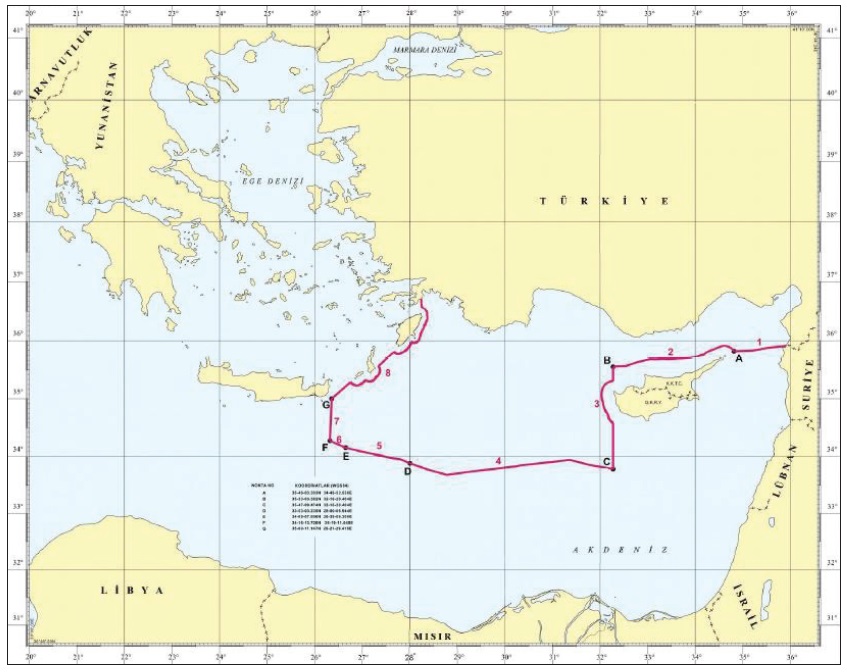

The agreement between Turkey and Libya on November 27, 2019, has been another step to clarify Turkey’s claim.30 The method adopted in the agreement is the median line emphasizing that the boundaries should be determined between the mainland of the respective countries. Turkey has recently issued an official map that shows the boundaries claimed by Turkey in the whole Eastern Mediterranean Sea. The map was circulated to the UN attached to the letter dated March 18, 2020, from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations.31 All the above-mentioned claims of Turkey over the course of Turkeys’ decided or claimed maritime boundary are therefore shown in a single map (Map 1).

Map 1: The Boundaries Claimed by Turkey in the Whole Eastern Mediterranean Sea

Source: Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations32

Source: Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations32

Turkey’s Legal Arguments to Justify Her Claims

Turkey’s Perception on Maritime Delimitation Law

Turkey emphasizes that conventional law and customary law do not provide different or separate rules for maritime delimitation. The conventional law, namely, Articles 74 (1) and 83 (1) of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) reflects customary international law so as to merge on the same fundamental principle of delimitation,33 which requires that delimitation between opposite or adjacent states should be achieved with an ‘agreement’ in order to produce an ‘equitable result.’34 It is emphasized that the ‘equitable result’ is the requirement of the main principle of maritime delimitation law, namely ‘the principle of equity.’35 When objecting to the very first Delimitation Agreement in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea between the GASC and Egypt, Turkey pointed out that delimitation should “be effected by agreement between the related states in the region based on the principle of equity,” indicating that the Egypt-GASC treaty was agreed upon without Turkey’s involvement and without the application of the principle of equity.36

Another significant aspect of Turkey’s view concerning the practical application of the delimitation rule relates to the role of islands in maritime delimitation

As opposed to the Greek insistence on ‘the principle of equidistance’ in maritime delimitation,37 Turkey points out that that equidistance is not a ‘principle of general applicability’ but merely one of the methods of maritime delimitation, which would be applied where it produces an equitable result in accordance with the principle of equity. It is stated clearly by Turkey that, “according to international law, including state practice, customary international law, international adjudication, and jurisprudence, the equidistance/median line method is applied only when its application does not distort equitable delimitation.”38 Therefore, equidistance is not a compulsory or the sole method to be applied in all delimitation cases.

The second significant point in Turkey’s legal approach relating to the delimitation law is that the fundamental rule of delimitation, i.e. ‘the principle of equity’ is applicable to the delimitation of all maritime areas including the territorial waters. This approach is evident in the Turkish Act No. 2674 of May 20, 1982,39 on the Territorial Sea of the Republic of Turkey, which provides that the “delimitation of the territorial sea between Turkey and other opposite or adjacent states shall be effected by agreement. The said agreement shall be concluded on the basis of the equitable principles and taking into account all special circumstances of the region.”40

Elaborating on the details of applying equity in practice, Turkey emphasizes certain specific principles of delimitation. These are the principles of ‘land should dominate the sea’; ‘there should be no ‘cut-off effect’ on the maritime areas of a coastal state’; and ‘there should be a reasonable degree of proportionality between the respective coasts and the maritime areas to be accorded.’41 These principles seem to be taken verbatim by Turkey from the jurisprudence of international courts.42

Within this general framework of equity, Turkey points to the particular geographical circumstances of the Eastern Mediterranean as a semi-enclosed sea

Another significant aspect of Turkey’s view concerning the practical application of the delimitation rule relates to the role of islands in maritime delimitation. The core of the related argument is that islands do not necessarily generate full maritime jurisdictional zones (continental shelf and/or exclusive economic zone) when they are against continental lands. The delimitation cases between the United Kingdom and France, Tunisia and Italy, Romania and Ukraine, Bangladesh and Myanmar, and Nicaragua and Colombia are all cited, as examples to demonstrate that islands should be ignored where giving full effect produces inequitable results.43

The final, but no less significant point, in the arguments of Turkey concerning the application of the principle of equity is that the “length of the coasts” must primarily be respected as the dominant geographical factor relevant to achieving an equitable delimitation. As required by the principle of proportionality, equity requires that there should be a reasonable degree of proportionality between the lengths of the relevant coasts of the two sides and the maritime areas to be accorded to them. Here, the wording “coasts” is used to connote the mainland coasts rather than those of islands.44

Reflections on the Eastern Mediterranean Sea

Turkey’s argument that delimitation should “be effected by agreement between the related States in the region based on the principle of equity” clearly indicates that the Egypt-GASC treaty and all the following treaties concerning the GASC were prepared and agreed upon without Turkey’s involvement and without the application of the principle of equity.45 The delimitation in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea should be achieved with the involvement of the related states by applying “equitable principles, taking into account all relevant or special circumstances.”46 Within this general framework of equity, Turkey points to the particular geographical circumstances of the Eastern Mediterranean as a semi-enclosed sea. As in all enclosed and semi-enclosed seas, the relevant or special circumstances of the Eastern Mediterranean must be respected.47

What are the relevant or special circumstances of the Eastern Mediterranean Sea that should be taken into account and respected? In accordance with the principle that the geographical factors should dominate the delimitation, the first element, according to Turkey, is the length of the Turkish coastline, which is ‘the longest’ in the Eastern Mediterranean. The element of longer coastline should therefore be taken into account and respected as a relevant or special circumstance.48

The second relevant factor to be respected is, according to Turkey, the coastal projection of the Turkish mainland, which should not be reduced by a possible cut-off effect of the Greek islands, as compared to their location and size.49 This is quite clear when Turkey stated that “islands cannot have a cut-off effect on the coastal projection of Turkey, the country with the longest continental coastline in the Eastern Mediterranean.”50

The Greek islands, namely Crete, Kasos, Karpathos, Rhodes, and Kastellorizo, should therefore be ignored altogether simply because giving maritime areas beyond their territorial waters would result in cutting off from the projection of the Turkish mainland so as to produce an inequitable result.51 This cut-off effect would, according to Turkey, disturb the geographical balance between the relevant mainlands. Turkey points out that “numerous rulings by the International Court of Justice have either completely ignored the islands that remain on the wrong side of the median line to generate maritime areas or given only partial effect in delimiting the maritime areas if their location distorts equitable delimitation…”52

Turkey also points to the “general geographical framework of the region” and argues that the Greek islands in the region are “minor features” within this general framework.53 This is quite clear in the case of the island of Kastellerizo, which is just 2 km away from the Turkish mainland and has an area of merely 10 km2. As to the island of Crete, which has an area of 8,300 km2, it would, according to Turkey, similarly disturb the geographical balance and equity if a sizable maritime area beyond its territorial waters is accorded.54 That should also be true for the islands of Rhodes and Karpathos, which are smaller and nearer to the Turkish mainland. Turkey makes it quite clear that “the islands which lie on the wrong side of the median line between two mainlands cannot create maritime jurisdiction areas beyond their territorial waters” and “the length and direction of the coasts should be taken into account in delineating maritime jurisdiction areas.”55

The island of Cyprus poses a different situation. Unlike the above-mentioned Greek islands in the region, it is not an island of another coastal State of the area but a political unit separate from any mainland country. Concerning its case, Turkey points to the fact that there is a considerable difference between the respective coastal lengths. Taking account of this factor, Turkey deems as equitable to give less maritime area to the island of Cyprus as compared to Turkey.56 This approach is evident both in the Delimitation Agreement between Turkey and TRNC and in the above-mentioned official map presented by Turkey to the UN to demonstrate the Turkish continental shelf boundary claim.

Turkey’s arguments as to the resource-related activities, which create high political tension, are worth mentioning. Turkey considers its resource-related activities as legitimate on the basis that Egypt and the GASC initially started such activities following their Delimitation Agreement in 2003. Turkey states that as they were not consulted or included57 before the agreement was signed, “as required by the established rules of international law,” Egypt and the GASC acted illegally leaving no option for Turkey but to start corresponding activities itself, in order to protect its rights. As long as they do not stop such ‘illegal’ activities in the region, Turkey is left with no option but to practically demonstrate and exercise its own rights in the field.58

The striking geographical factor that stands out in Turkey’s arguments is the disparity between the coastal lengths of Turkey and those of its neighbors

Turkey has a specific approach to the existing political status over the island of Cyprus with regard to the maritime delimitation dispute in the region. Delimitation of the continental shelf, according to Turkey, “is related to the comprehensive settlement of the Cyprus question, and thereafter maritime boundaries should be determined through negotiations.” Moreover, Turkey argues that “there is no single authority that in law or in fact is competent to represent jointly the Turkish Cypriots and the Greek Cypriots, consequently Cyprus as a whole. The Greek Cypriots cannot claim authority, jurisdiction, or sovereignty over the Turkish Cypriots, who have equal status, or over the entire island of Cyprus.”59

As clarified in this statement, the Greek Cypriots can neither sign delimitation agreements with the countries of the region nor conduct oil/natural gas exploration activities in the Eastern Mediterranean without the involvement of the Turkish side of the island. Otherwise, it would “prejudge and violate the fundamental and inherent rights and interests of the Turkish Cypriot people.” Such agreements and conducts should “be left to the discretion of the new partnership government, where Turkish and Greek Cypriots will share power on the basis of political equality.”60

Conclusion

The fragile political atmosphere in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea is the result of the ongoing maritime boundary disputes. This fact significantly affects the political, legal, and practical approaches of all related states with regard to any process of settlement. Turkey’s legal arguments, as summarized above, relate to both the Maritime Delimitation Law in general and its application to the specific context of the Eastern Mediterranean Sea. Turkey generally lays strong emphasis on ‘the principle of equity’ and ‘equitable solution.’ This is clearly the main delimitation rule, established through customary international law and the relevant articles of the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea61 and endorsed in all the relevant international jurisprudence.62 Turkey also emphasizes the equitable principles of maritime delimitation as identified in the relevant international jurisprudence.63

The way in which Turkey applies these principles to the case of the Eastern Mediterranean reveals many significant aspects of Turkey’s legal approach. The striking geographical factor that stands out in Turkey’s arguments is the disparity between the coastal lengths of Turkey and those of its neighbors. This is a geographical factor that, according to Turkey, should be respected to allocate larger maritime areas of continental shelf/EEZ to Turkey.

Again, based on the maritime jurisprudence,64 Turkey also argues that Greek islands, which are situated closer to the Turkish mainland, should not be given any maritime areas beyond their territorial waters. Otherwise, this would cut-off from the coastal projections of the Turkish mainland, distort geographical balance, and inevitably result in an inequitable delimitation. The case of the island of Cyprus is taken separately in some respects. Since the GASC has signed various delimitation agreements and conducts activities ignoring the Turkish side of the Island, which has equal rights over the waters around the Island, Turkey regards all these treaties and acts as legally unfounded.

Apart from the exclusion of the Turkish side, Turkey specifically objects to the GASC-Egypt delimitation treaty and related activities because they also infringe on the continental shelf/EEZ rights of Turkey in the West of the Island. The island of Cyprus should be given restricted maritime areas as compared to Turkey due to its much shorter coastlines. Turkey emphasizes that all these have eventually left no choice for Turkey but to make delimitation agreements and conduct resource-related activities in order to protect its own rights.

Endnotes

1. Some of these examples are: “The United Kingdom and France Arbitration, Award of March 14, 1978,” Reports of International Arbitral Awards, Vol. XVIII, pp. 3-413; “Canada and France Arbitration, Award of June 10, 1992,” International Legal Materials, Vol. 31, pp. 1149-1178; “Eritrea and Yemen (Maritime Delimitation) Arbitration, Award of December 17, 1999,” Reports of Internatıonal Arbitral Awards, Vol. XXII, pp. 335-410; “Qatar and Bahrain Case, Judgment of March 16, 2001,” ICJ Reports, (2001), p. 40; “Romania Ukraine Case, Judgment of February 3, 2009,” ICJ Reports, (2009), p. 61; “Nicaragua v. Colombia Case, Judgment of December 13, 2007,” ICJ Reports, (2007), p. 832.

2. There is some relevant information on the issue. See, “Names and Limits of Oceans and Seas,” International Hydrographic Organizations, Vol. 23, No. 4, (June 2002), pp. 3-14; Sertaç Hami Başeren, Doğu Akdeniz Deniz Yetki Alanları Uyuşmazlığı, (İstanbul: TÜDAV Yayınları, 2010), p. 2.

3. See, “The Bay of Bengal Maritıme Boundary Arbitration between the People’s Republic of Bangladesh and the Republic of India, Award,” (July 7, 2014), p. 287.

4. “Maritime Space: Maritime Zones and Maritime Delimitation,” The UN Division of Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea, (December 13, 2019).

5. GASC declared EEZ approximately one year after the signature of the EEZ delimitation agreement with Egypt. See, “Law to Provide for the Proclamation of Exclusive Economic Zone by the Republic of Cyprus,” UN, (April 2, 2004), retrieved from https://www.un.org/Depts/los/LEGISLATIONANDTREATIES/PDFFILES/cyp_2004_eez_proclamation.pdf.

6. Some disagreements were announced by the TRNC over possible acts of the GASC over the delimitation of maritime areas earlier than that treaty. Başeren, Doğu Akdeniz Deniz Yetki Alanları Uyuşmazlığı, p. 36.

7. “Information Note by Turkey Concerning Its Objection to the Agreement between the Republic of Cyprus and the Arab Republic of Egypt on the Delimitation of Exclusive Economic Zone, February 17, 2003,” Law of the Sea Bulletin, No. 54 (2004), p. 127.

8. “Information note by Turkey, Concerning Its Objection to the Agreement between the Republic of Cyprus and the Arab Republic of Egypt on the Delimitation of the Exclusive Economic Zone, February 17, 2003.”

9. Following the treaty signed with Egypt on January 26, 2007, the GASC announced 13 parcels in the region for exploring natural resources and began drilling in the 12th parcel on September 11, 2011. In addition, the GASC made a call for license applications in some other areas on February 11, 2012. “Kıbrıs Rum Kesimine Protesto,” Anadolu Agency, (February 15, 2012). On September 19, 2011, the GASC started to work with Noble Energy. “Turkish Oil Exploration Ship Sets Out to Contest Cyprus Drill Rights,” Cyprus Mail, (September 24, 2011); Yöney Yüce, “Exclusive Area of Conflict,” Bianet English, (September 20, 2011).

10. See for instance, The Letter dated March 17, 2016 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General. A/70/788–S/2016/257.

11. The treaty is not yet ratified by Lebanon, and therefore not in effect.

12. Upon the signing of the GASC-Egypt EEZ delimitation agreement dated February 17, 2003, TRNC Foreign Minister Tahsin Ertuğruloğlu officially declared on February 24, 2003 that, the TRNC did not recognize the signed treaty. The President of the TRNC Talat also said in a statement that “the oil around Cyprus should be used jointly, otherwise hostile conditions will occur.” President Talat sent written statements to express his warnings to both Lebanese and Egyptian governments. The TRNC also challenged the GASC-Lebanon EEZ Delimitation Treaty dated January 17, 2007, on the same grounds. Başeren, Doğu Akdeniz Deniz Yetki Alanları Uyuşmazlığı, p. 37.

13. See, the letter dated June 20, 2011 from the Minister for Foreign Affairs and Emigrants of Lebanon addressed to the Secretary-General of the United Nations signed in Nicosia on 17 December 17, 2010. 14/07/2011 1 2082.11D. retrieved from https://www.un.org/Depts/los/LEGISLATIONANDTREATIES/PDFFILES/communications/lbn_re_cyp_isr_agreement2010.pdf.

14. See, the Letter dated February 13, 2014 from the Permanent Representative of Cyprus to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General. A/68/759; Letter dated February 29, 2016 from the Permanent Representative of Cyprus to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General. A/70/767–S/2016/20; Letter dated October 17, 2013 from the Permanent Representative of Cyprus to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General. A/68/537–S/2013/622; Annex to the letter dated June 15, 2012 from the Permanent Representative of Cyprus to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General. A/66/851.

15. See, Resmi Gazete, The Official Gazette, (October 10, 2012), NO. 28437. The treaty was approved and published by the TRNC Council of Ministers on November 23, 2011.

16. The TRNC issued a natural resource exploration license to the TPAO in the 7th block of the outlined parcels on September 22, 2011, with a formal agreement signed between the company and the TRNC on November 2, 2011. Some of the licensed areas are located in the South of the Island and coincide with areas that were claimed by the GASC. Such activities appear to still be intermittently conducted. See, Annex to the letter dated January 10, 2020 from the Chargé d’affairesi. of the Permanent Mission of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General. A/74/648–S/2020/28.

17. Although Turkey has not declared EEZ in the Eastern Mediterranean, the mention of EEZ in this Memorandum is common in other state practices too. Some countries have determined the boundary to be applied when declared, by making treaties establishing the EEZ boundary without declaring EEZ.

18. The Treaty was later ratified by Turkish Parliament and published in Turkey’s Official Gazette on December 7, 2019. See, Annex to the letter dated February 27, 2020 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General. A/74/727.

19. Letter dated February 14, 2020 from the Permanent Representative of Greece to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General. Annex to this letter is the Letter dated December 9, 2019 from the Permanent Representative of Greece to the United Nations Addressed to the Secretary-General. A/74/706. (February 19, 2020). Website of the Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea; Letter dated December 9, 2019 from the Permanent Representative of Greece to the United Nations Addressed to the Secretary-General.

20. See, Note Verbale dated December 23, 2019 from the Permanent Mission of Egypt to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/74/628, Website of the Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea; Letter dated August 1, 2020 from the Permanent Representative of Egypt to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/74/978.

21. Letter dated April 29, 2020 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General. A/74/831.

22. EU Foreign Affairs and Security Policy High Representative Josep Borrell in a written statement from his office stated that the EU continues to be in full solidarity with Cyprus within the framework of activities of Turkey in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Aegean Sea. “AB’den Türkiye’ye: Libya ile Yapılan Anlaşma Metni Geciktirilmeden Bize Ulaştırılmalı,” Euronews, (December 5, 2019).

23. Note verbale dated August 14, 2020 from the Permanent Mission of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/74/990. See also, the letter dated August 21, 2020 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/74/997–S/2020/826.

24. “Information Note by Turkey concerning its Objection to the Agreement between the Republic of Cyprus and the Arab Republic of Egypt on the Delimitation of Exclusive Economic Zone, February 17, 2003.” Law of the Sea Bulletin, No. 54 (2004), p. 127. See also, Letter dated March 17, 2016 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/70/788–S/2016/257; Letter dated April 28, 2016 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/70/855–S/2016/406.

25. The letter dated September 29, 2016 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/71/421. Turkey clearly pointed out in a communication to the UN that these areas “fall entirely within the Turkish continental shelf where Turkey exercises exclusive sovereign rights for the purpose of exploring and exploiting its natural resources of the seabed and subsoil under international law, both customary and case.” Annex to the Letter dated September 5, 2012 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/66/899. At, https://undocs.org/A/66/899.

26. See, Resmi Gazete, The Official Gazette, (April 27, 2012), No. 28276. The area is shown in the map attached to the decision of the Council of Ministers of Turkey.

27. The Letter of the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the UN: 2013/14136816/22273, (March 8, 2013).

28. Letter dated April 28, 2016 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/70/855–S/2016/406.

29. Letter dated August 21, 2020 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/74/997–S/2020/826. According to Turkey, the main delimitation line in that specific sub-region should be established by Turkey and Egypt giving the Greek islands no effect. Letter dated June 15, 2016 from the Chargé d’affairesi. of the Permanent Mission of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/70/945–S/2016/541. See also, Letter dated March 27, 2018 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/72/820.

30. Resmi Gazete, the Official Gazette, (December 7, 2019), No. 30971.

31. The map attached to the Letter dated 18 March 2020 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/74/757.

32. The Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General. A/74/757, retrieved February 2021, from https://undocs.org/en/a/74/757.

33. Letter dated November 13, 2019 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/74/550.

34. Turkey clearly pointed out that “the fundamental principle according to international law governing the delimitation of continental shelf and exclusive economic zone between States with opposite or adjacent coasts is to produce an equitable result (principle of equity).” Letter dated November 13, 2019 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/74/550.

35. See, The Letter of the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the UN: 2013/14136816/22273. (March 8, 2013). See, also the Letter dated June 15, 2016 from the Chargé d’affairesi. of the Permanent Mission of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/70/945–S/2016/541; Letter dated July 2, 2020 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/74/936.

36. Information Note by Turkey concerning its Objection to the Agreement between the Republic of Cyprus and the Arab Republic of Egypt on the Delimitation of Exclusive Economic Zone, (February 17, 2003).

37. See, for instance, Letter dated April 25, 2019 from the Chargé d’affairesi. of the Permanent Mission of Greece to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General. A/73/850 S/2019/344, (April 30, 2019).

38. Letter dated November 13, 2019 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General. A/74/550. Within this framework of view, Turkey considers a Greek internal law, namely Article 2(1) of the Greek Law 400/17/2011, as contrary to international law since it attempts “to establish continental shelf and exclusive economic zone boundaries through a median line between continental land masses and insular formations.” The Letter of the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the UN: 2013/14136816/22273, (March 8, 2013).

39. Resmi Gazete, No. 17708, (May 29, 1982).

40. Article 2.

41. The Letter dated June 15, 2016 from the Chargé d’affaires a.i. of the Permanent Mission of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/70/945–S/2016/541

42. Yücel Acer, “Deniz Alanlarının Sınırlandırılması Hukuku,” Sertaç H. Başeren (eds.), Doğu Akdeniz’de Hukuk ve Siyaset, (Ankara: AÜSBF Yayınları, 2013), p. 309.

43. The Letter dated June 15, 2016 from the Chargé d’affairesi. of the Permanent Mission of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/70/945–S/2016/541.

44. The Note Verbale dated August 14, 2020 from the Permanent Mission of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/74/990.

45. Information Note by Turkey concerning its Objection to the Agreement between the Republic of Cyprus and the Arab Republic of Egypt on the Delimitation of Exclusive Economic Zone, (February 17, 2003).

46. The Annex to the Letter dated September 5, 2012 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/66/899. See also, Letter dated November 13, 2019 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/74/550.

47. The Letter of the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the UN: 2013/14136816/22273, (March 8, 2013). See also, the Annex to the letter dated September 5, 2012 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/66/899, retrieved from https://undocs.org/A/66/899.

48. The Letter dated April 28, 2016 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General. A/70/855–S/2016/406; Letter dated March 18, 2019 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/73/804.

49. Turkey has clearly stated this approach, in a letter dated March 15, 2019 sent to the UN and summarizing the approach of Turkey to maritime jurisdiction areas in the Eastern Mediterranean. Responding to question about the explanations of Greece and Egypt towards Turkey-Libya agreement being illegal, Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesman Hami Aksoy said “This is an agreement signed in special accordance with court decisions that make up the precedents of international law, including the relevant articles of United Nations Conventions on the Law of the Sea.” Aksoy stated that all parties were actually aware that, “Turkey’s coastal projection will not be cut with the islands, the islands in the opposite side of the median line between the two mainlands will not create maritime jurisdiction areas outside the territorial waters, and coastal lengths and directions are taken into account when calculating the maritime jurisdiction areas.” “Türkiye’nin Hamlesi Yunanistan’ı Şaşkına Çevirdi! Şah ve Mat!” CNN Türk, (December 2, 2019).

50. The Letter dated March 18, 2020 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/74/757.

51. Note Verbale dated August 14, 2020 from the Permanent Mission of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/74/990.

52. The Letter dated July 2, 2020 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/74/936.

53. The Letter dated August 21, 2020 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/74/997–S/2020/826.

54. The Letter dated August 21, 2020 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/74/997–S/2020/826.

55. The Letter dated March 18, 2020 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/74/757.

56. Tuğrul Çam, “Dışişleri Bakanlığı Türkiye’nin Doğu Akdeniz’deki Kıta Sahanlığı ve MEB Sınırlarını Paylaştı,” Anadolu Agency, (December 2, 2019). Deputy General Director of Bilateral Political Affairs and Maritime-Aviation Border, Çağatay Erciyes: “Greek Cypriots and Greek islands do not have the right to automatically create a continental shelf and exclusive economic zone. In the delimitation, the private locations of the islands are looked at, the coastal lengths are examined, the geography they are located in is noted, and the islands are not given any maritime jurisdiction in international court decisions or bilateral agreements.” “Doğu Akdeniz: Türkiye-Libya Anlaşması Bölge Dengeleri Nasıl Etkiler?”BBC Türkçe, (December 10, 2019).

57. Turkey’s letters sent to the UN Secretary-General dated July 23, 2007 and August 8, 2007. Ministry of Foreign Affairs Hami Aksoy stated that “Turkey called the parties to negotiate within the frame of equity before signing this agreement and still is ready to negotiate but instead of beginning negotiations in the face of Turkey’s approach based on international law and justice, the option of only unilaterally taking steps to accuse Turkey has been followed.” “AB’den Türkiye’ye: Libya ile Yapılan Anlaşma Metni Geciktirilmeden Bize Ulaştırılmalı,”

58. Turkey’s letters sent to the UN Secretary-General dated July 23, 2007 and August 8, 2007.

59. Annex to the Letter dated September 5, 2012 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/66/899, retrieved from https://undocs.org/A/66/899; Letter dated March 17, 2016 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/70/788–S/2016/257: Letter dated September 29, 2016 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/71/421; Annex to the letter dated January 10, 2020 from the Chargé d’affairesi. of the Permanent Mission of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/74/648–S/2020/28; Letter dated July 2, 2020 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/74/936; “Regarding the Efforts of the Greek Cypriot Administration of Southern Cyprus to Sign Bilateral Agreements Concerning Maritime Jurisdiction Areas with the Countries in the Eastern Mediterranean,” Republic of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs, (January 30, 2007); “Press Release Regarding the Greek Cypriot Administration’s Gas Exploration Activities in the Eastern Mediterranean,” Republic of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs, (August 5, 2011), No. 181.

60. Annex to the Letter dated May 30, 2014 from the Chargé d’affairesi. of the Permanent Mission of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/68/902. See also, the Annex to the letter dated October 20, 2016 from the Chargé d’affaires a.i. of the Permanent Mission of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/71/562–S/2016/890; Annex to the letter dated December 14, 2016 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/71/693 S/2016/1067; Letter dated July 2, 2020 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General, A/74/936.

61. Article 74, paragraph 1 the 1982 Law of the Sea Convention reads as follows. “The delimitation of the exclusive economic zone between States with opposite or adjacent coasts shall be effected by agreement on the basis of international law, as referred to in Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice, in order to achieve an equitable solution. Article 83 (1) similarly reads: “The delimitation of the continental shelf between States with opposite or adjacent coasts shall be effected by agreement on the basis of international law, as referred to in Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice, in order to achieve an equitable solution.”

62. The International Court of Justice in the North Sea Cases, observed that “delimitation must be the object of an agreement between the States concerned, and that such agreement must be arrived at in accordance with equitable principles,” p. 85. “The North Sea Continental Shelf Cases,” ICJ Reports, (1969), p. 3. This principle has been endorsed in all following decisions.

63. See for instance, “North Sea Cases,” (1969), p. 91; “Tunisia-Libya Case,” ICJ Reports, (1982), par. 73; “Canada-France Case,” International Legal Materials, Vol. 31, (1992), par. 24; “Jan Mayen Case,” ICJ Reports, (1993), par. 51-53; “Qatar-Bahrain Case,” ICJ Reports, (2001), p. 185.

64. There are many such examples in which islands situated similar to those of Greece in the region are treated in the same way Turkey proposes. See, for instance, “The United Kingdom-France Delimitation Arbitration,” pp. 201- 202.