In 2003, the United States launched an ambitious nation-building project in Iraq and has little to show for it. Iraq is not united and non-sectarian, nor is it a beacon of democracy in the region, the goals of U.S. nation-building. Washington’s influence is limited and depends entirely on Iraq’s need for support against ISIS. Iran on the other hand, which never talked of nation-building, has penetrated Iraqi politics and society, establishing the conditions for its own long-lasting influence.

The Iraqi state today has been shaped more deeply by Iran than by the United States. The Iranian version of nation-building, based on building up organizations that share its goals, has trumped that of the United States, which depends on superimposing on Iraq institutions the U.S. thinks the country should have and training people to staff them. A Shia-dominated government is in place in Baghdad, and U.S. efforts to portray it as “inclusive” do not stand up to factual analysis. To be sure, the top government positions and ministries are divided among representatives of Shia, Sunni and Kurdish parties. But Shia militias armed and trained by Iran and the Kurdish peshmerga are now the country’s main defense against the Islamic State, while the national army –made up of “weaklings” in the words of a Shia militia leader– is barely beginning to be reconstructed by the United States after collapsing without a fight in June 2014 and again walking out of the fight in Ramadi a year later.

The contrast between Iran’s success and the United States’ failure offers some important lessons about nation-building

The major Iraqi Shia political parties and militias were set up in Iran in the 1980s and the ties remain strong. The Iranian al-Quds Force continues to arm and train Shia militias and even participates in some of their operations, at least in an advisory capacity and possibly as a fighting force.

Iran has won the first battle for influence in Iraq and the contrast between Iran’s success and the United States’ failure offers some important lessons about nation-building. Iran gained influence by building on Iraq’s sectarian divisions, and the resentment and aspiration of Iraqi Shias. Iran had nothing to offer other population groups, but its policies had the strong buy-in of an influential and powerful part of Iraqi society. The United States sought to promote national unity and decrease sectarian divisions, a noble goal in theory, but one that offered Iraqis an alien political and social model and thus was not embraced by any group. The model of nation-building Iran has followed successfully so far, shaping the country through de facto alliances with Shia forces, may make it impossible for Iraq to survive as one country. Paradoxically, Tehran does not want a divided Iraq any more than Washington does.

The United States: Grafting a New State

The United States invaded Iraq at the peak of the western nation-building enthusiasm that followed the fall of socialism. It is important to recapture the ebullience of the moment. Serious scholars were arguing earnestly that democracy had triumphed over other ideologies and that history had ended. Practitioners in USAID and consulting firms believed that they really could help new, inexperienced democracies consolidate their government institutions and civil societies. The enthusiasm spawned a democracy industry, which metastasized into a more ambitious nation-building industry in conflict-ridden countries, Bosnia in particular. By the early 2000s, scholars and practitioners were drawing up more and more complex models of what nation-building entailed, breathtaking in their social and political engineering ambition and in their lack of realism.

These ideas influenced policies in Iraq. Although the United States had ostensibly invaded Iraq to get rid of Saddam Hussein, not to turn it into a pluralistic, tolerant, well-integrated democratic country with an active civil society, equality for women, and a prosperous free-market economy, these and many other reforms quickly became part of the agenda. The massive “Future of Iraq” project launched by the US State Department in early 2002 produced a thirteen-volume study outlining a comprehensive nation-building program. The report discussed plans for Water, Agriculture and the Environment; Public Health and Humanitarian Needs; Defense Policy and Institutions; Economy and Infrastructure; Transparency and Anti-Corruption; Education; Transitional Justice; Democratic Principles and Procedures; Local Government; Civil Society Capacity Building; Free Media; Oil and Energy; and more. Essentially, it called for the impossible: a complete social, political and economic re-engineering of Iraq.

The feasibility of the plan was never put to a test. The Pentagon, which took charge of both the war and the project of reconstruction in Iraq, discarded the State Department plan and set up the Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance (renamed the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) in May 2003). Guided by expediency rather than an overall plan, the CPA had a strong impact on the future of Iraq, although not the one it intended. Two decisions in particular contributed to exacerbating Iraq’s sectarian conflict: the complete disbanding, rather than the reforming, of the Iraqi Army, and the launching of an extensive and ill-defined de-Ba’athification effort, that is, the culling from government ranks of members and above all officials of Saddam’s Ba’ath party. Both moves engendered much resentment among Sunnis – incidentally, the “Future of Iraq” project had warned that such measures should not be taken. A third decision with long-lasting consequences was that of accelerating the transfer of some power back to Iraqis, and to rely on the existing parties formed along sectarian lines in doing so.

The CPA never completely abandoned the idea of a comprehensive nation-building program like the one envisaged by the “Future of Iraq” project. Without the resources or know-how to do what was probably impossible in the first place, it addressed in piecemeal fashion issues as diverse as the reorganizing of Iraq’s provincial government, the building of civil society, and even the development of a stock exchange –for good measure, Congress mandated at one point the building of two state-of-the-art fire stations. But having deposed Saddam Hussein, eliminated the Ba’ath Party and disbanded the military, the CPA was forced to concentrate its efforts on developing new national level political and military institutions. Inevitably, it promoted institutions it was familiar with and values it upheld. Grafted onto Iraq, the institutions failed or became distorted, and the values did not take. The March 2013 report of the Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction, “Learning from Iraq,” concluded that the Iraq reconstruction program was beset by waste, inefficiency, and lack of buy-in by Iraqis. Between fifteen and twenty percent of the money spent by the US in Iraq was wasted, according to the report, but the lack of buy-in was the most serious problem.

US Vice President Joe Biden and Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi hold a meeting of the US-Iraq Higher Coordinating Committee in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building on April 16, 2015. | AFP PHOTO / SAUL LOEB

US Vice President Joe Biden and Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi hold a meeting of the US-Iraq Higher Coordinating Committee in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building on April 16, 2015. | AFP PHOTO / SAUL LOEB

The political transition plan eventually adopted by the CPA virtually precluded a buy-in, as Iraqis were rushed through a process that left no time for discussion. Early rumblings of discontent among Iraqis convinced U.S. officials in July 2003 to set up Iraqi Governing Council with a limited advisory role. By November, the CPA and Iraqi representatives had reached an agreement on a transition plan to achieve Iraqi self-government. It included the drafting of a provisional constitution (the Transitional Administrative Law), the transfer of power to an Iraqi transitional government and thus the formal restoration of Iraq’s sovereignty in June 2004, followed by the election of a National Assembly in January 2005, the formation of a new transitional government, the drafting of a new Constitution and its approval by referendum, culminating in elections for a new parliament in December 2005.

The U.S. political goals for Iraq were to maintain the unity of the country at all costs; to promote democracy; but also, contradictorily, to ensure that Iraq would have a strong leader. On the military front, the United States sought to train a professional army and police force. These were American goals not shared by Iraq’s most important political forces.

Ironically, the unity of Iraq was a divisive concept, accepted by Sunnis and rejected by Kurds, with Shias switching their position back and forth. The Kurds never pretended that their ultimate goal was anything but independence. The influential (and Iran-aligned) Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq, SCIRI (which became ISCI after dropping the word “revolution” from its name) in 2005 the idea of a large autonomous Shia region including nine provinces. ISCI continued to advocate a Shia autonomous region until 2010, when it joined other Shia parties in the hope of winning the parliamentary elections and ruling the country. But the idea of regional autonomy slowly gained new acceptance among all population groups, even Sunnis, as a reaction against Iraq’s centralization under Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki. Provincial councils resented Baghdad’s control and their own lack of financial autonomy, looking with envy at the rapid economic progress being made by autonomous Kurdistan. But the Maliki government resisted all requests by provincial councils to allow the formation of more regions like Kurdistan.

The idea of democracy was more widely accepted by Iraqis than that of unity. But the way in which a democratic system was introduced led many Sunnis to feel left out and marginalized. And indeed Sunnis were underrepresented in the 2005 parliament that enacted the new constitution, the outcome of a long chain of events culminating in a misguided decision by Sunni parties to boycott the January 2005 elections.

Despite their support for democracy, U.S. officials were convinced that Iraq needed a strong leader capable of holding the country together. When Maliki was first chosen as prime minister in early 2006 as a weak compromise candidate, U.S. officials fretted that he was not up to the job. When Maliki became more assertive, they chose to disregard the alarming authoritarian and sectarian tendencies he was beginning to display. Washington thus backed him for a second term in 2010, although he was also Iran’s preferred candidate. Maliki promptly proceeded to establish his personal control on the military, largely dismantling the professional army the United States had sought to train. He further alienated Sunnis, particularly the so-called Sons of Iraq, the tribal militias funded by the U.S., which had played a crucial role in the fight against al-Qaeda after 2006. When the United States withdrew its troops from Iraq in 2011, the Maliki reneged on the promise to continue paying the militias and integrate its members in the military. The strong leader the United States had wanted for Iraq ended up undermining both democracy and unity.

The United States’ goals for the new Iraqi military and police forces were also not widely accepted by Iraqi leaders. Washington was committed to the concept that the military and police forces must be neutral, non-sectarian, professional, and firmly under the oversight of a democratic government. Such a concept was alien to Iraqi politicians, who wanted security forces they could personally control and mobilize in the struggle for power among factions. During the first wave of sectarian fighting around 2006, the police force controlled by the Ministry of Interior turned into a Shia militia controlled by a partisan minister, and the United States was forced to restart the process. Other organizations also had their own militias. Renewed efforts at vetting and training Iraqi personnel by the United States attenuated the problem for a while, but it flared up again after the withdrawal of American troops in 2011. Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki hastened to establish his control over military and police, appointing top officers on the basis of loyalty rather than competence. He also kept the Ministry of Interior in his own hands throughout his second term in office, and the Ministry of Defense for a period of nine months. The politicization of the officers’ corps, coupled with rampant corruption, resulting in the depletion of the ranks by the presence of thousands of ghost soldiers – individuals who drew salaries and shared them with their commanding officers while working elsewhere – led to a loss of both morale and fighting capacity that contributed to the military’s collapse without a fight when confronted by ISIS in June 2014.

Another problem that plagued the U.S. training of Iraqi security forces was the difficulty of retaining trained personnel. The retention problem was graphically documented in the fluctuations, at times dramatic, in the number of “Iraqi security forces on duty.” Between June and July 2004, for example, the number of police plummeted from 83,000 to 31,000. Similar fluctuations occurred in the reported level of readiness of the forces. While the figures are certainly imprecise, they accurately tell the story of a training program beset by problems. A 2010 CSIS study by Andrew Cordesman, based on reports by the Special Inspector General for Iraq (SIGIR), concluded that the attrition rate in the Iraqi Forces remained as high as 25 percent. Not only did this problem weaken the security forces; it also created a large reservoir of men with military training, many of who have probably joined ISIS or the Shia militias.

Iran: Penetrating the State

Iran did not try to shape a new Iraqi state. Instead, it penetrated Iraq’s political organizations. Iran’s efforts date back to the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war and continued after the U.S. invasion. As a result of its head start, Iran was able to embed itself in the new system the United States was trying to develop and to outcompete the United States for influence in Iraq.

When relations between Baghdad and Tehran were at their most hostile during the 1980-88 war, Iran provided embattled Iraqi Shia clerics a refuge and supported their efforts to form political movements and militias. The Da’wa Party and the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq, supported and sheltered by Iran during the war, became integral part of the politics of Iraq. When the CIA helped launch the Iraqi National Congress in 1991 in the hope it would overthrow Saddam Hussein, the Iranian-backed parties joined. They gained representation in the transitional Iraqi Governing Council the CPA set up in 2003, and won seats in the Council of Representatives in the 2005 elections and all later ones. All Iraqi prime ministers since 2005 have been members of the Da’wa Party, although Nouri al-Maliki eventually formed a new organization called the State of Law without changing his ties to Iran or his sectarian inclinations. U.S. intelligence agencies knew about the ties between Iran and major Shia organizations in Iraq, but this does not appear to have affected policy.

Iran also became embedded in Iraq’s security system through the militias it helped develop and continued to support. While the United States was endeavoring to shape an American-style, professional, non-sectarian and apolitical military operating under civilian oversight, as well as a new police force, Iran- trained and -backed Shia militias were seeking to infiltrate the new forces, turning them into tools in a sectarian power struggle.

Among the political organizations formed by exiled clerics in Iran, ISCI was particularly important because it had an armed wing, the Badr Brigades (or Badr Corps), trained by the Iranian al-Quds Force. The Brigades fought against Saddam Hussein in the Iran-Iraq war and then supported the Shia uprising that started with the 1991 Gulf War. When Saddam Hussein succeeded in crushing the uprising, the Badr Brigades retreated back into Iran and only returned to Iraq in 2003. Shortly thereafter, the organization changed its name to the Badr Organization for Reconstruction and Development and, paying lip-service to the U.S. insistence that all militias must be disbanded, announced that it had disarmed. With its new political façade, the Badr Organization saw its leader appointed Minister of the Interior, a convenient position from which to infiltrate the new police force the United States was training. As a result, in 2007 the United States was forced to restart the vetting and training of the police force.

The unity of Iraq was a divisive concept, accepted by Sunnis and rejected by Kurds, with Shias switching their position back and forth

While the Badr Organization was getting stronger under the leadership of Hadi al-Ameri, ISCI was getting weaker. ISCI’s head Abdulaziz al-Hakim died in 2009, and his son Ammar did not command the same degree of authority and respect. ISCI lost its central role in Shia politics. The Badr organization presented its own candidates for the 2010 parliamentary elections and broke completely with ISCI in 2012.

When the Islamic State occupied Mosul and a large part of northeastern Iraq in June 2014, Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani, the highest Shia authority in Iraq, issued a fatwa calling on Iraqi citizens to defend their country and its sacred places. This call gave a new role and legitimacy to the Shia militias (al-Sistani’s call may not have been directed exclusively to Shias, but it was Shias who responded). Then Prime Minister al-Maliki followed up on Sistani’s appeal by establishing an umbrella organization to coordinate the militias, al-Hashd al-Shaabi (or Popular Mobilization). Al-Ameri responded immediately, mobilizing its followers and making the Badr Organization the most important component of the Popular Mobilization forces. Al-Ameri himself became the most influential leader in the Popular Mobilization forces, although not formally in command. Other Shia militias with links to Iran joined in quickly and new groups also emerged.

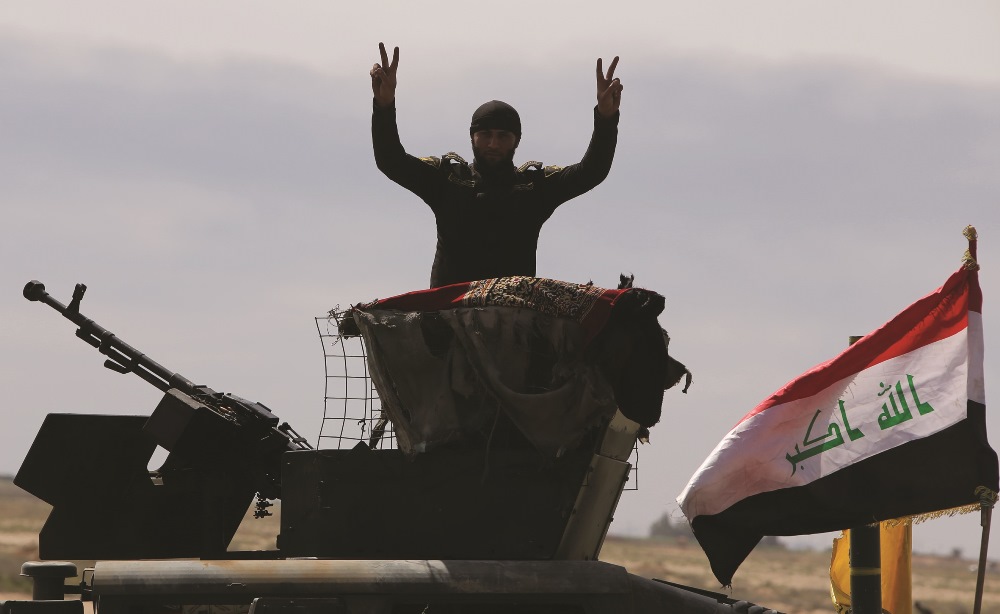

An Iraqi Shiite fighter and member of Iraq’s Popular Mobilisation Units (al-Hashd al-Shaabi) supporting the Iraqi government forces in the battle against ISIL on March 8, 2015. | AFP PHOTO / AHMAD AL-RUBAYE

An Iraqi Shiite fighter and member of Iraq’s Popular Mobilisation Units (al-Hashd al-Shaabi) supporting the Iraqi government forces in the battle against ISIL on March 8, 2015. | AFP PHOTO / AHMAD AL-RUBAYE

Not all Shia militias became part of the Popular Mobilization Forces. Most notably Moqtada al-Sadr, descendant of a family of illustrious clerics active in the resistance to Saddam Hussein and the fiery leader of the Sadrist trend, kept his forces independent. Sadr always had poor relations with Maliki –his Mahdi Army had repeated confrontations with the Iraqi armed forces and was dismantled in 2008 after a particularly violent confrontation. The Sadrist organization and its armed wing also had a more complicated relation with Iran than other major Shia militias, having developed in Iraq, where Moqtada’s father and uncle had remained, rather than in exile in Iran. Nevertheless, Moqtada al-Sadr and the Mahdi army soon came under Iranian influence, with Moqtada seeking refuge across the border when conditions became too difficult domestically. Moqtada’s Mahdi Army has been revived as the Peace Companies, and has participated to some extent in the fight against ISIS. The Peace Companies continue to play an opaque political role independent of other militias.

The war against ISIS has provided Iran with another opportunity to remain a dominant player in Iraq though its support for Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Forces. It has also provided the United States with another chance to regain some influence in Iraq. With its long-standing ties to political organizations as well as militias, Iran has been able to make a smooth transition from politics to military battle. The al-Quds Forces are openly engaged in supporting the militias, with the only unanswered question being whether they are just providing weapons and training or are directly involved in combat. (Pictures of General Qassem Soleimani, the commander of the al-Quds forces, with members of the militias have been widely circulated, but they may be a better indicator of a successful propaganda effort than of engagement on the battlefield). The United States is also operating as it did in the past: it has resumed efforts to prepare the Iraqi military to defeat ISIS by turning it into the professional, American style military it sought and failed to develop before 2011. Once again, Iran appears to be successful. The militias have so far proven a more effective force against ISIS than the military, because the U.S. training efforts are slow and ponderous, and even American advisors recognize they will take time. The militias, on the other hand, just jump into the fray.

There are lessons the United States ought to learn from Iran’s success and its own failure, even if its goals will always be different from Iran’s

The United States is also seeking again to shape Iraq’s political system along the lines it envisaged earlier, as a united and non-sectarian country, a goal that is still not supported by any major Iraqi political organization or personality. Prime Minister al-Abadi, committed on paper to an inclusive government in order to receive U.S. support, has taken no real steps to change the Shia bias of the government. As in the past, Iran is not trying to superimpose its own vision of Islamic government on Iraq, but is instead supporting political organizations and militias. The approach has been extremely successful from Iran’s point of view. The downside going forward is that Iran is becoming deeply enmeshed in the looming struggle for power between al-Maliki, who lost his position as prime minister, and current Prime Minister al-Abadi. Al-Maliki is close to the Popular Mobilization forces and apparently sees them as a possible avenue to renewed power. Al-Abadi needs U.S. support to revive his military, and thus needs to keep the militias in check, but when he tries to keep them away from a battle, as happened in Ramadi, ISIS gains ground. Iran’s influence may be affected by this inter-Shia power struggle.

Lessons for the United States

The United States and Iran have been competing with each other in Iraq, and so far Iran has been much more successful than the United States. Iran is closely linked to Iraq’s major political organizations and militias, the diversity of which divides the country but also gives Iran much influence. On the other hand, despite its enormous display of military force, costly investment in reconstruction and deliberate attempt at nation-building, the United States does not have much to show. Prime Minister al-Abadi cooperates with the United States out of necessity, but he appears somewhat ambivalent and certainly there is no groundswell of support in the country for a renewed American presence. Elements of the Shia Popular Mobilization forces have repeatedly threatened to withdraw from the battlefield if the U.S. participates in an operation by bombing. The Sunni tribal forces that rallied to the side of the United States to fight al-Qaeda in the past are now distrustful of both Washington and Baghdad. Kurds, in general the most pro-American group in Iraq, complain bitterly that they love the United States but they are not loved by it in return.

The political goal of a united, democratic Iraq with strong but non-authoritarian leadership does not have enough support to succeed

There are lessons the United States ought to learn from Iran’s success and its own failure, even if its goals will always be different from Iran’s. The most important is that Iran was successful because it did not try to impose its model on Iraq, but started from the demands and needs of specific groups, helped them pursue their goals, and made itself an indispensable ally for some. To be sure, Iran followed a sectarian policy, supporting only Shia leaders, parties and militias. It favored Shia clerics over secular Shias like Iyad Allawi, who in 2010 managed to obtain the vote of many Sunnis as well as of Shias unwilling to support religious parties. Certainly, Iran did not reach out to the Sunni population –probably a doomed effort in any case. It did, however, manage to find a modus vivendi with Kurdistan, allowing trade across the border, including the smuggling of oil, and even working to build a pipeline to export gas to Kurdistan, whose rapidly increasing domestic gas production could not keep up with the growing requirements of its power plants.

The United States came in with ready-made political and economic models. It wanted a united Iraq, but also a federal system as long as it was not one built on sectarian divisions. It wanted elected provincial councils because it believed this would give the government greater legitimacy, without asking whether Iraqis felt the same way. It funded new civil society organizations and trained new political parties. It was a good model in theory, but not one enjoying the support of large, organized forces and thus it failed.

The policy might possibly have succeeded in the event of a much longer occupation, many more troops, and a more vigorous and better-coordinated reconstruction effort –in other words, with the kind of full-fledged nation-building program imagined by some. This is only speculation, of course, and in any case such policy would not have been politically sustainable in the United States at the time, and is even less so now. If the United States wants to re-establish lasting influence in Iraq, rather than being manipulated by Iraqis who want its support but do not want to comply with its demands, it needs to learn from Iran and rethink its goals in view of what Iraq’s important political forces want.

The military goal of defeating ISIS is broadly-shared in Iraq, and it could be even more broadly shared if Sunnis saw the possibility of a better deal than the present illusory “inclusive government” where power is de facto in Shia hands and centralized in Baghdad. But to increase the chances that ISIS will be defeated militarily soon, the United States has to accept the reality that the Shia militias are an indispensable force at present, even if their participations means that Iran and the United States are de facto

allies. The presence of Shia militias in Sunni-majority areas is undoubtedly worrisome, but not as worrisome as seeing ISIS gaining even more control. And the U.S. has to accept the fact that Kurds are fighting for Kurdistan, not Iraq.

The political goal of a united, democratic Iraq with strong but non-authoritarian leadership, on the other hand, does not have enough support to succeed, so the goal has to change to something that has the support of major groups in Iraq. This does not mean betraying American ideals, just discarding an unworkable model and helping Iraqis find compromises that would work for them. Any solution must start from what exists now: a Kurdistan that will never settle for less than even greater autonomy than it has now, and eventually seeks full independence; the Sunnis’ complete distrust of the Baghdad government, coupled with demands for greater control by provincial councils and tribal leaders alike; the reality of Shia domination of any national elections, coupled with a growing demand for regional autonomy in the Shia provinces, particularly the oil-producing ones. All these factors suggest the need for an extremely decentralized and possibly messy solution –in the way the solution in Bosnia has been messy. Difficult? Of course. But better than what the United Sates has been trying to achieve, which is impossible.