“At a certain point in their historical lives, social classes become detached from their traditional parties. In other words, the traditional parties in that particular organisational form, with the particular men or women who constitute, represent and lead them, are no longer recognised by their class (or fraction of a class) as its expression. When such crises occur, the immediate situation becomes delicate and dangerous, because the field is open for violent solutions, for the activities of unknown forces, represented by charismatic ‘men of destiny.’” Antonio Gramsci

“Let us wage a moral and political war against the billionaires and corporate leaders, on Wall Street and elsewhere, whose policies and greed are destroying the middle class of America.” U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders

Introduction

The rise of Donald Trump to the presidency of the United States is symptomatic of a deep crisis of American identity and the power and hegemony of the ruling class, particularly of its market-led globalism. American globalism’s corporate core-dynamic has produced gross inequalities of income and wealth that have colonized its political culture and institutions. This has produced a diversionary but deeply-rooted, carefully-nurtured domestic politics characterized by class-based ‘pluto-populist’ white nationalism.1 Internationally, there are challenges from re-emerging powers from the global South, like China and India, demanding a renegotiation of power in the U.S.-led order, and with (rhetorical) nationalist-historical narratives of humiliation during Western colonial rule.2 Conversely, those re-emerging powers, and their elites, have grown influential within the U.S.-led globalist order and therefore sit atop unequal and unstable societies, as they rapidly industrialize and urbanize. Finally, the United States and Europe face refugee/migration crises partly spawned by U.S.-led military interventions in the Middle East resulting in blowback terrorism and ISIS insurgency.3 America’s population appears to have less appetite for external interventions and global hegemony and are polarized on the fundamental question of what America stands for.4

The Democratic Party opposition, with the corporate media, intelligence/military services, and elite think tanks, by its side, appears to be continuing its ‘centrist’ status quo political strategy as the best way to defeat Trump in 2020

The American elite’s legitimacy crisis is multisided and deep, at home and abroad. The Trump presidency is unlikely to resolve it due to its divisive, nationalistic, “America First” character, despite the administration's reversal of headline attacks on the U.S.-led international order. The Democratic Party opposition, with the corporate media, intelligence/military services, and elite think tanks, by its side, appears to be continuing its ‘centrist’ status quo political strategy as the best way to defeat Trump in 2020. It is still tied to Wall Street donors, and a series of investigations around alleged collusion between the Trump election campaign and the Russian state to defeat Hillary Clinton in November 2016.5 Meanwhile, Trump’s cabinet of billionaires plans to abolish what remains of social safety nets for the most vulnerable in American society, reduce spending on environmental regulation, deregulating healthcare, banks, and other major corporate sectors, and weaken labor protections. Proposed tax cuts to the very richest suggest inequality is set to continue or increase, exacerbating the legitimacy crisis as Trump’s economic nationalist program fails to deliver well-paid jobs to enough workers in the “rust belt” states who propelled him to the presidency.6

Should the above scenario materialize, the United States should expect major political and social unrest, a significant part of which will be racialized and/or ‘Islamophobic’ in character. This is, at its core, a racialized class-based politics mobilized by the right that divides society and prevents the formation of a unified reform strategy to shift income, wealth and power away from the billionaire class or establishment towards the “99 percent.”7

Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders delivers a major policy address on Wall Street reform in New York on January 5, 2016. | AFP PHOTO / KENA BETANCUR

Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders delivers a major policy address on Wall Street reform in New York on January 5, 2016. | AFP PHOTO / KENA BETANCUR

The biggest challenge facing the U.S.-led liberal international order is to genuinely embrace diversity at home and abroad and strategies to reduce class inequality. The problem, however, is that the maintenance of dominant class economic-financial interests and elite political power is implicated in racialized politics. Liberal politics professes a greater attachment to diversity but remains racialized at heart; its attachment to diversity is but a thin veneer shrouding the continuation of racialized class-based inequality on a large scale, even as highly talented minorities ‘make it.’8 On the right, diversity remains a distant secondary goal to ‘color blind’ equality of opportunity, obscuring large-scale racial discrimination and maintenance of a racialized class system.9 Indeed, the Republican right has been reversing African-Americans’ civil rights era voting rights.10 Liberals and right wingers therefore work effectively in tandem to reproduce a hierarchical racial-class system at home –until recently a system of “racism without racists”11– dovetailing with America’s approach to global South emerging powers.12

Race is the available politically-salient fault line nurtured and exploited to maintain the power and influence of an oligarchy of wealth in the United States. In the current period, racial politics works specifically by dividing predominantly white voters from the “outsider” –the minority, the refugee, Muslim, the illegal immigrant– who allegedly leech off the welfare system, taxpayers’ generosity, and hate America’s values. In this scenario, it is white Americans who are the most racially-disadvantaged, an anxiety and anger long exploited by the Republican Party and pandered to by the Democrats.13 In certain terms, the same or similar is considered true of America’s allies –“taking advantage” of U.S. military resources and goodwill while refusing to pay their fair shares, while rising competitor states like China manipulate their currency, “dump” cheap steel onto the American market, and take American jobs.14

The legitimacy crisis of America’s political-economic elites is deep, clear, serious, likely to last, and likely to feature significant political strife unless elite politics is reformed to loosen the power of big money and open up political agendas to encompass significant political and economic reform

Trump’s pluto-populism (billionaire-led calls to the masses to rise up against the political establishment) is the most overtly racialized class politics since the 1960s –its political message of “America First,” “taking America back,” making it “great again” wrapped up in an openly racist Islamophobia speaks to a sense of white loss and yearning for a golden age. Such a divisive message is, however, a major roadblock to domestic stability as it generates mass opposition as well as judicial intervention to overturn unconstitutional executive orders. It not only fails to address, but is part of, the economic problem at the heart of the body politic –economic inequality and polarization alongside a politics dominated by big money that sets agendas that are narrow, market-oriented and favor low taxes and small government. Abroad, it means continued problems in accepting emerging powers as equals in the international system, with attendant political difficulties, and the continuation of racialized warfare across parts of the non-white world.15

Legitimacy Crisis

The legitimacy crisis of America’s political-economic elites is deep, clear, serious, likely to last, and likely to feature significant political strife unless elite politics is reformed to loosen the power of big money16 and open up political agendas to encompass significant political and economic reform. Unfortunately, as historian Howard Zinn pointed out, political change in America takes large-scale, widespread and prolonged political turmoil and usually violence to effect.17 In addition, signals from the main opposition Democratic Party as to readiness to lead such an effort at political reform are discouraging.18 Yet, signs of mass alienation and discontent seem quite clear.19

Robert Reich tells a story of a book tour of the ‘flyover states’ –the places between the American East and West coasts that liberals fear to tread and are dominated by rock-ribbed Republicans– in the summer of 2015. His experience was instructive: the liberal academic and former Secretary of Labor to President Clinton found to his shock that hard core GOP voters were outraged by the political leadership of both main political parties and wanted to throw out the political establishment in Washington D.C. They had had enough of the corrupt politics of the political leadership of the United States and their rich corporate donors.20

Bernie Sanders’ primary election campaign garnered 13 million votes –for an overtly socialist program aimed at gutting the power of Wall Street, and implicated the Democratic National Committee’s preferred candidate with the politics of the establishment and the billionaire class. He openly endorsed a politics of class conflict that pitted the billionaire class against the vast majority of working and middle class Americans in a society that was deeply unequal and wedded to the politics of the dollar rather than satisfying Americans’ aspirations for fair reward for hard work, healthcare for all, adequate investment in American infrastructure, and a college education that would not leave graduates in massive debt.21 Not since Eugene Debs ran for the Socialist Party in 1912 and 1920 –when he won almost 2 million votes in total– has a socialist candidate generated so much support in the United States. Sanders lost the primaries, of course, but it was clear that the Democratic National Committee (DNC) conspired to favor Clinton via the super-delegates system that almost guaranteed a Clinton victory. In addition, both main candidates were aided by a corporate-dominated media which provided disproportionately less airtime to the socialist candidate as compared to Clinton and Trump (the latter won 13 million primary votes in the Republican contest). Finally, it was also clear that the New York Times, Washington Post and other media outlets of the liberal establishment sided with Clinton in undermining the Sanders campaign and dismissing his economic policy as deeply flawed and bound to fail.22

Hillary Clinton’s own public standing was poor throughout the election campaign, just ahead of the public approval levels of Donald Trump. Trump was the most negatively viewed presidential candidate in Americans’ eyes but Clinton came a close second. The choice before the people in November 2016 was therefore between the lesser of two evils.23

In office, President Trump’s approval ratings are among the lowest recorded at so early a stage of an administration –hovering around a mere 40 percent. There has been no ‘honeymoon’ for President Trump,24 so divisive was his campaign and promulgation of executive orders to ban Muslims from several countries from entering the United States, amongst other regressive actions.

On the other hand, the Democratic Party’s approval ratings also remain low in the wake of the election of former Labor Secretary Tom Perez to DNC chair and the decision to lift the ban on Wall Street donations to the DNC.25

Major shifts in American politics, its global strategies, economy and political culture, occurred in the 1970s which, in combination, constructed the atmosphere and issues that propelled Donald Trump to the White House in 2016

Conversely, there are major moves afoot to recast U.S. politics following Senator Bernie Sanders’ unexpected successes.26 The movement has sprouted a Sanders Institute to mobilize progressive congressional candidates across the U.S. According to Sanders, candidates may get support in fundraising and hustings, even if they happen to be progressives from the Tea Party. Former Labor Secretary Robert Reich has spoken of a new progressive party –the kind of organizations that are now in motion may well lead to such an outcome.27

The Sanders Institute’s aim is to conduct political-ideological work on the key issues of power, wealth and inequality that struck a chord during his bid for the Democratic nomination. Although he has not endorsed it, some of his supporters are also actively aligning their work with the Green Party, which previously asked Sanders to run for the White House on their ticket. Its candidate, Jill Stein, hovered around 5 percent in presidential election polls.28

Brand New Congress is another key group from the Sanders wing of the Democratic Party. It is a political action committee that aims to identify and support hundreds of non-politician candidates for over 400 congressional seats with the aim of replacing the entire House by the mid-term elections in 2018. Formed in April 2016, in a matter of weeks it raised nearly $100,000 in small donations and is looking to the future –without Wall Street big money politics.29 It complements the Sanders Institute’s plan to back 100 progressive candidates in congressional, state and local elections in November 2016.

Similarly, Sanders’ Our Revolution organization aims to build on his campaign and revitalize democracy, empower progressives to run for school board elections, mayoral offices and take on big money politics. It also seeks to “elevate political consciousness,” take on the corporate media, educate the public and improve public discourse and understanding.30

Trump’s non-conservative statist message and campaign rhetoric along with Clinton’s ‘shift’ to the left showed that there are big changes afoot in the fabric of American politics.31 Even Wall Street now agrees that wages must rise, infrastructure needs investment and inequality has reached extreme levels.

U.S. President Donald Trump standing alone during one of the working sessions of the G20 summit in Hamburg on July 8, 2017. | AFP PHOTO / POOL / MARKUS SCHREIBER

U.S. President Donald Trump standing alone during one of the working sessions of the G20 summit in Hamburg on July 8, 2017. | AFP PHOTO / POOL / MARKUS SCHREIBER

Nevertheless, these are early days and no political outcome is certain. There is much going on, but there is no returning to normalcy after 2016. The major trends of 2016 emerged out of longer term developments that had increasingly alienated Americans and manifested in insurgencies from both left and right –most prominently in the form of the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street movements.32 Both movements expressed deeply held frustrations with their respective party leaders, gathering pace with the election of Barack Obama in 2008, the fallout of the Iraq war and the post 9/11 war on terror, the financial meltdown of 2008, and the continuing problem of inequality amid the politics of affluence funded by a tiny minority of large donors.33

A 1970s Moment, but Worse

America has been in a place like this before –in the 1970s, but this time it’s worse; 2016 represents a key tipping point that has been decades in the making. In 1974, Harvard’s Samuel P. Huntington diagnosed a “crisis of democracy” that had overtaken America in the 1960s, unleashing demands for “democratic surge and… democratic egalitarianism.” Opposition to the Vietnam War, movements for racial and gender equality, against political and governmental corruption led people to question the system of government including the “legitimacy of hierarchy, coercion, discipline, secrecy, and deception –all of which… are inescapable attributes of the process of government.” Too many people who had previously expected little from government –blacks, women, and students– were demanding opportunities and privileges previously denied to them. There was an “excess of democracy” rather than the usual, and necessary, rule of a few men from Wall Street law firms and banks, media and foundations. Participatory democracy, to Huntington, appeared as chaos and disorder.34

A new “grand bargain” at home and abroad that rebalances economy and politics away from the power of Wall Street and big money may be required; one that redraws the character of America’s global engagement towards a more realistic assessment of its power and role in a changing world

Major shifts in American politics, its global strategies, economy and political culture, occurred in the 1970s which, in combination, constructed the atmosphere and issues that propelled Donald Trump to the White House in 2016. At home, corporate counter-mobilizations re-established the ideas and politics of free enterprise as the backbone of America, seen in myriad ways –in the rise of new right think tanks like Heritage Foundation, funded by corporate foundations like Coors, corporate funding of the main political parties as their battles intensified and, eventually the rise of a conservative establishment rivalling the ‘liberal’ establishment by the 1990s.35

Allied shifts towards a consumer culture fueled by cheap money and debt, and the rise of women workers, masked the actual stagnation of real wages from the mid-1970s and beyond. Standards of living improved but people were spending future earnings in an economy that was heading towards deindustrialization or post-industrialism partly by design and partly by basic technological development.36

The 1960s ‘rights revolution’ established the Democrats as the party of minorities –women and blacks– and the GOP as the new home of erstwhile white working/middle class male Democrats. The latter made their voices heard with a landslide victory for Ronald Reagan in 1980 and three consecutive defeats for the Democrats. By the early 1990’s, a profound reorientation of the Democratic Party towards the Clintonite third way was well underway including a fundamental rejection of the New Deal order. The ‘angry white male’ besieged by independent women, assertive racial minorities, “politically-correct” language, and a sense of loss of a 1950s America, in which they occupied the apex of America, traces his (re)birth to the 1970s.37

Cementing that position was the radically changed position of the 1970’s U.S. in the world: defeated in Vietnam, unable/unwilling to independently to exert dollar domination, a loosening of post-1945 relationships with more assertive Japan and Western Europe, forcing détente with the Soviet Union, facing the OPEC oil crisis, and a collective demand from the ‘third world’ for a New International Economic Order.38 Huntington’s crisis of democracy at home was twinned with a crisis of American authority on the global stage. The response, in part, to the latter was of long-term significance –globally and at home. A long-term ‘solution,’ to be sure, which brought us to where we are today.

The Third World, it was argued, was really not homogeneous; there was an aspirational ‘middle class’ part of that world that could be brought into the U.S.-led liberal order through investment and loans. This merely played into current trends of globalization of the U.S. economy and the export of capital and manufacturing to the middle class third world –India, Mexico, Turkey, Venezuela, and later China, not to mention the East Asian tiger economies.39

The net effect was that white workers and their middle class counterparts turned their backs on the Democrats and were psychologically assuaged in their new home –the GOP as the ‘white man’s party’– but received little in the way of benefits from low taxes and small government. In reality, the latter formulation was a reaction to and targeted at the poor and minorities, but it impacted on so-called ‘rust belt’ states –Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. The globalized free market and the corporations that fed the new right’s ideology chased profits by opening new territories across the world –in low wage economies. Shipbuilding, coal mines, steel factories, auto manufacturers were among the sectors of the economy that witnessed the export of jobs, plant and machinery, as well as their migration within the United States, to neighbors, for example, across the border in the maquiladora economy.40

The decline of organized labor and the inexorable rise of financial elite power over state and economy had profound effects on political culture, institutions, policy and agendas.41 Consumption through debt and money making money, drove growing inequality of income and wealth from the mid-1970s,42 bled into party politics through big money and into the very halls of power, alienating masses of people from the political and economic order.

Yet, despite these seismic changes in the terrain of American politics, economy and society, economic growth in the 1980s and 1990s –fueled by consumer debt– managed to keep a lid on discontents. But the twenty-first century has seen the results come home to roost –fueled by the effects of the Iraq war, the war on terror and the 2008 financial crisis.43

The Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street were major responses from left and right signaling a legitimacy crisis that neither party heeded; Trump and Sanders, and the defeat of Hillary Clinton, was their political manifestation in 2016. The seeds of the present crisis were sown in the 1970s and have now borne bitter fruit

Yet, the conservative political-ideological mix of low taxes and federal social spending cuts delivered very little to working class whites, African Americans –middle class or working class– or other minorities. Income and wealth inequality44 grew rapidly as Wall Street bankers amassed greater fortunes and increasingly bankrolled election spending by both main political parties, set political agendas and further reinforced the disconnect between the electorate and political power.45 The financial crash of 2008 produced federal bailouts and rescue packages for major banks to the tune of trillions of dollars but little by way of relief for ordinary people. The Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street were major responses from left and right signaling a legitimacy crisis that neither party heeded; Trump and Sanders, and the defeat of Hillary Clinton, was their political manifestation in 2016. The seeds of the present crisis were sown in the 1970s and have now borne bitter fruit.

Conclusion: What Now?

A new “grand bargain” at home and abroad that rebalances economy and politics away from the power of Wall Street and big money may be required; one that redraws the character of America’s global engagement towards a more realistic assessment of its power and role in a changing world. Trump and Sanders are not only the symptoms of a crisis; hidden in their core appeal and message lies a beta test of a political cure. And the core of it is a new kind of politics based on grassroots mobilizations around economic, financial and the role of the U.S. in world issues.46 Those matters have become so tightly held in the grip of America’s political elites –Republican and Democratic bipartisanship– with attendant benefits of wealth, privilege and power to the few, that the voices of ordinary voters have been stymied.47 The mantra of ‘there is no alternative’ to the free market or big money domination of politics, or the belief in militarily-fueled U.S. global primacy, has been heavily damaged from left and right. This lack of credibility impacted Hillary Clinton’s platform and campaign, signaling a new normal in U.S. politics. November 2016 cannot inaugurate any ‘return to normalcy’ that ignores the Trump and Sanders phenomenon. Centrist policies in American politics –as a viable political or governing strategy– have been narrowed to the point of potential extinction.

But are American political and economic elites up to the challenges of change? After all, they are the very people whose leadership has brought their country, and the world, to this point.

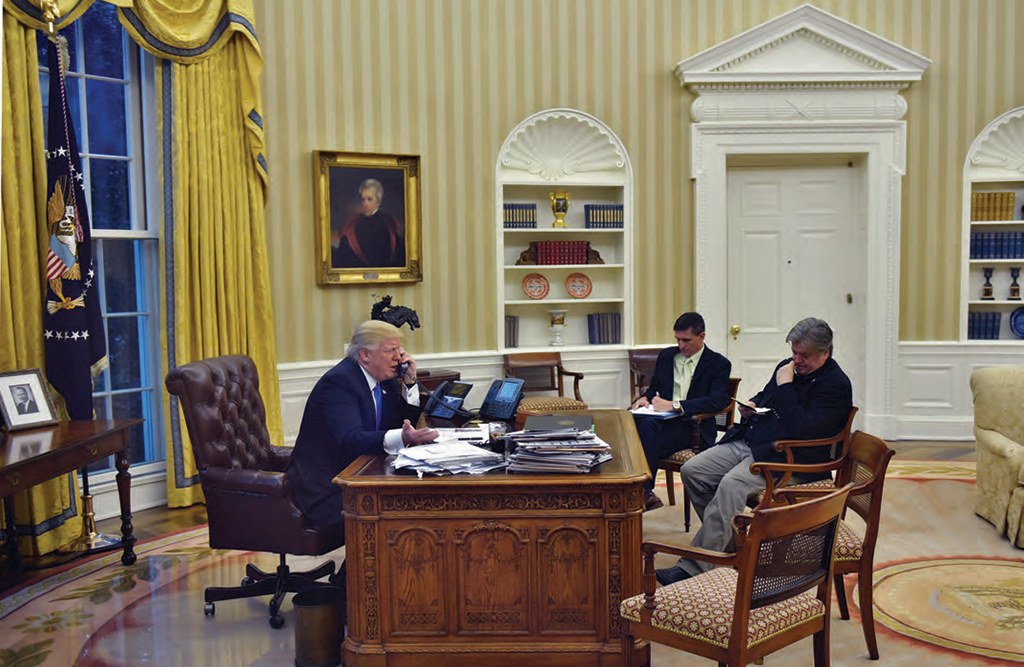

Trump speaking on the phone in the Oval Office, alongside Chief Strategist Steve Bannon and former National Security Advisor Michael Flynn. | AFP PHOTO / MANDEL NGAN

Trump speaking on the phone in the Oval Office, alongside Chief Strategist Steve Bannon and former National Security Advisor Michael Flynn. | AFP PHOTO / MANDEL NGAN

Change in America has never been easy or gradual; it has usually followed serious violence. The United States was born in violent revolution, waged wars against Native Americans, enslaved Africans, fought a bloody civil war a few decades later, and witnessed bloody labor struggles for union rights and higher pay, and state and corporate repression of anti-war radicals and reformers of various stripes. It is a myth that real change has been peacefully won through mere political lobbying of Congress or democratic elections. Real change has come as a result of massive political resistance against injustice and for workers, women’s and minority rights, often met with state and private vigilante violence which ultimately altered the environment within which political leaders operated and fundamentally shifted party politics.48 Non-violent direct action mobilizations like Black Lives Matter, Occupy Wall Street, the Tea Party, the ‘Battle in Seattle’ against globalization; movements like Democracy for America, feminist, anti-war and labor organizations –these are most likely to bring about the conditions of real change. Movements like these may well be the ones to, force shifts in the nature and objects of politics, and the established party system and dealing with the master problem of inequality of income, wealth and power. The old categories of left and right have been rendered almost meaningless as Democrats and Republicans complain about core issues: globalization’s effects on high-paying industrial jobs, anxieties about ever-increasing competition and future prospects, free trade, low taxes for the rich, rampant corporate power in economy and politics, expensive health care, and a feeling of loss –of prospects of ever achieving the ‘American dream’ itself.

If established elites, with Trump in the White House, will not embrace the need to reform the system, despite rising mass discontent, the United States may well experience a period of political violence and disorder that dwarfs the tumultuous sixties uprisings of the civil, women’s and anti-war movements

Ultimately, the sources of political and economic change lie in mass protest alongside the production of reform backed by new ideas and alliances that shift power away from moneyed interests towards the people. If established elites, with Trump in the White House, will not embrace the need to reform the system, despite rising mass discontent, the United States may well experience a period of political violence and disorder that dwarfs the tumultuous sixties uprisings of the civil, women’s and anti-war movements. The difference next time will be stark, however. The 1960s inaugurated extensions of democracy and rights to minorities excluded by race, gender and class. The “fire next time” appears to be arising between those who want a return to a golden age when white, male power ruled supreme, against an America that wants an open, diverse and egalitarian. The current leadership and line of the two main parties is in crisis and will continue to be deeply affected by the developing legitimacy crisis, unless they adapt and renew. Unfortunately, current establishment politics appears unable to envision anything other than the restoration of the pre-Trump era and a return to normalcy that seems increasingly unlikely.

Endnotes

- Martin Wolf, “Donald Trump’s Pluto-populism Laid Bare,” Financial Times, (May 2, 2017); “The Rise of Populism,” The New Statesman, (July 2, 2016). Trump has developed politics as a “concrete fantasy which acts on a dispersed and shattered people to arouse and organize its collective will…” Antonio Gramsci, cited in Walter Adamson, Hegemony and Revolution, (Berkeley, CA: UCLA Press, 1980).

- William Callahan, China: The Pessoptimist Nation, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012); Shashi Tharoor, Inglorious Empire, (London: Hurst, 2017).

- Patrick Cockburn, The Rise of Islamic State, (London: Verso, 2014); John Pilger, “Terror in Britain: What Did the Prime Minister Know?” com, (May 31, 2017), retrieved June 7, 2017 from http://johnpilger.com/articles/terror-in-britain-what-did-the-prime-minister-know.

- Carl Conetta, Something in the Air: ‘Isolationism’, Defense Spending and the US Public Mood, (Center for International Policy Report, October 2014), retrieved March 30, 2017 from https://www.ciponline.org/images/uploads/publications/Something_in_the_Air.pdf; Inderjeet Parmar, “Super Tuesday Just Redefined American Politics,” Fortune, (March 2, 2016), retrieved June 7, 2017 from http://fortune.com/2016/03/02/super-tuesday-american-politics/; Michael Kimmel, Angry White Men, (New York: Nation Institute, 2013); J. D. Vance, Hillbilly Elegy, (New York: HarperCollins, 2016).

- Inderjeet Parmar, “The American Establishment vs Pluto-populist President Trump,” The Wire, (May 25, 2017); Zack Beauchamp, “Democrats Are Falling for Fake News about Russia,” Vox, (May 19, 2017), retrieved June 7, 2016 from https://www.vox.com/world/2017/5/19/15561842/trump-russia-louise-mensch; Seymour Martin Lipset, “Prejudice and Politics in the American Past and Present,” in Charles Y. Glock and Ellen Siegelman, (eds.), Prejudice USA, (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1969).

- Robert Reich’s Inequality Monitoring Site, retrieved from https://www.inequalitymedia.org/; Martin Wolf, “Donald Trump’s Tough Talk Will Not Bring US Jobs Back,” Financial Times, (January 31, 2017).

- Martin Gilens and Benjamin I. Page, “Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens,” Perspectives on Politics, Vol. 12, No. 3 (2014); Cornel West, “Goodbye American Neoliberalism. A New Era Is Here,” The Guardian, (November 17, 2016); Randolph B. Persaud, “The Rise of Trump’s ‘White Wall’ Means that 2017 Will Not Be a Good Year for Politics,” LSE US Centre Blog, retrieved June 7, 2017 from http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/usappblog/2017/01/05/the-rise-of-donald-trumps-white-wall-means-that-2017-will-not-be-a-good-year-for-politics/.

- Inderjeet Parmar and Mark Ledwidge, “…’a Foundation Hatched Black…’: Obama, the US Establishment, and Foreign Policy,” International Politics, First online April 2017; G. William Domhoff and Richard Zweigenhaft, Diversity in the Power Elite, (Lanham, Md: Rowman and Littlefield, 2006); Mark Ledwidge, Kevern Verney, and Inderjeet Parmar (eds.), Barack Obama and the Myth of a Post-Racial America, (London: Routledge, 2014).

- Kevin Phillips, The Emerging Republican Majority, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014).

- Andrew Cohen, “How Voter ID Laws Are Being Used to Disenfranchise Minorities and the Poor,” The Atlantic, (March 16, 2012); Virginia Hench, “The Death of Voting Rights: The Legal Disenfranchisement of Minority Voters,” Case Western Reserve Law Review, Vol. 48, No. 4 (Summer 1998).

- Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, Racism without Racists, (Lanham, Md: Rowman and Littlefield, 2014).

- Oliver Turner, American Images of China, (London: Routledge, 2014); Edward Said, Orientalism, (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1978); Shane Maddock, Nuclear Apartheid, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010).

- Kimmel, Angry White Men; Mike King, “Aggrieved Whiteness: White Identity Politics and Modern American Racial Formation,” Abolition Journal, (May 4, 2017), retrieved June 8, 2017 from https://abolitionjournal.org/tag/aggrieved-whiteness/.

- Republican National Committee Platform 2016, retrieved June 8, 2017 from https://prod-cdn-static.gop.com/media/documents/DRAFT_12_FINAL[1]-ben_1468872234.pdf.

- Jamie Allinson, “The Necropolitics of Drones,” International Political Sociology, Vol. 9, No. 2 (2015), pp.113-127; Henry Giroux, “War Culture, Militarism and Racist Violence under Trump,” retrieved December 16, 2016 from http://com/story/war-culture-militarism-racist-violence-trump/.

- Jane Mayer, Dark Money, (New York: Penguin Random House, 2017).

- Howard Zinn, On History, (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2014).

- Lucia Mutikani and Doina Chiacu, “Democrats Must Overhaul Party, Fight Big Business, Says Bernie Sanders,” The Wire, (February 27, 2017), retrieved June 8, 2017 from https://thewire.in/

112200/democrats-must-overhaul-party-fight-big-business-says-sanders/; “Democratic Party Elections Reveal Growing Populist Energy,” Wall Street Journal, (February 26, 2017). - “Beyond Distrust: How Americans View Their Government,” Pew Research Center, (November 23, 2015), retrieved June 8, 2017 from http://www.people-press.org/files/2015/11/11-23-2015-Governance-release.pdf.

- Robert Reich, “The Oddest Presidential Election in Living Memory,” Commonwealth Club (Video Lecture), (September 27, 2016), retrieved June 8, 2017 from https://www.commonwealth.org/events/2016-09-27/robert-reich-oddest-presidential-election-living-memory.

- Inderjeet Parmar, “2016 Was a Great Year in US Politics, 2017 Will Be Even Better,” The Wire, (December 26, 2017), retrieved June 8, 2017 from https://thewire.in/89510/us-politics-trump-clinton-sanders/.

- “Research: Media Coverage of the 2016 Election,” Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, retrieved June 8, 2017 from https://shorensteincenter.org/research-media-coverage-2016-election/.

- Lydia Saad, “Trump and Clinton Finish with Historically Poor Images,” Gallup, (November 8, 2016), retrieved June 8, 2017 from http://www.gallup.com/poll/197231/trump-clinton-finish-historically-poor-images.aspx.

- Jeffrey M. Jones, “Trump’s Job Approval in First Quarter Lowest by 14 Points,” Gallup; (April 20, 2017), retrieved June 8, 2017 from http://www.com/poll/208778/trump-job-approval-first-quarter-lowest-points.aspx?g_source=Trump+approval&g_medium=search&g_campaign=tiles.

- Jeffrey M. Jones, “Democratic Party Image Dips, GOP Ratings Stable,” Gallup, (May 16, 2017), retrieved June 8, 2017 from http://www.gallup.com/poll/210725/democratic-party-image-dips-gop-ratings-stable.aspx?g_source=Democratic+party+approval&g_medium=search&g_campaign=tiles.

- Bernie Sanders, Our Revolution. A Future to Believe In, (London: Profile Books, 2017); “Bernie Sanders to Mark the ‘Turning Point’ of His Revolution,” The Guardian, (June 9, 2017), retrieved June 9, 2017 from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/jun/09/bernie-sanders-peoples-summit-chicago-political-revolution?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other.

- Inderjeet Parmar, “How Will the Sanders Revolution Work if Hillary Clinton Becomes President?” The Wire, (September 9, 2016), retrieved June 8, 2017 from https://thewire.in/65070/will-hillary-clinton-live-up-to-the-promises-of-sanders-revolution/.

- See: The Sanders Institute, https://www.sandersinstitute.com/.

- See: Brand New Congress, https://brandnewcongress.org/.

- See: Our Revolution, https://ourrevolution.com/.

- “The Most Progressive Platform Ever,” Washington Post, (July 12, 2016), retrieved June 8, 2017 from https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/the-most-progressive-democratic-platform-ever/2016/07/12/82525ab0-479b-11e6-bdb9-701687974517_story.html?utm_term=.b6be8cbd41b7.

- Theda Skocpol and Vanessa Williamson, The Tea Party and the Remaking of Republican Conservatism, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016); Kate Crehan, Gramsci’s Common Sense: Inequality and Its Narratives, (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016).

- David Roberts, “Political Donors in the US Are Whiter, Wealthier, and More Conservative than Voters,” Vox, (December 9, 2016), retrieved June 8, 2017 from https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2016/12/9/13875096/us-political-

- Samuel P. Huntington, Michel Crozier, and Jōji Watanuki (eds.), The Crisis of Democracy: Report on the Governability of Democracies of the Trilateral Commission, retrieved June 8, 2017 from http://trilateral.org/download/doc/crisis_of_democracy.pdf.

- Inderjeet Parmar, “Foreign Policy Fusion: Liberal Interventionists, Conservative Nationalists, and Neo-conservatives – the New Alliance Dominating the US Foreign Policy Establishment,” International Politics, Vol. 46, No. 2-3 (2009), pp. 177-209.

- Barry Bluestone and Bennett Harrison, The Deindustrialization of America, (New York: Basic Books, 1982); Robert Reich, The Work of Nations, (New York: Vintage, 1992).

- Kimmel, Angry White Men; Arlie Russell Hochschild, Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right, (New York: The New Press, 2016).

- Jennifer Bair, “Taking Aim at the NIEO,” in Philip Mirowski and Dieter Plehwe, (eds.), The Road from Mont Pelerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), pp. 347-385; Philip S. Golub, “From the New International Economic Order to the G20,” Third World Quarterly, Vol. 34, No. 6 (2013), pp. 1000-1015.

- Tom Farer, “The United States and the Third World: A Basis for Accommodation,” Foreign Affairs, (October 1975); Holly Sklar, (ed.), Trilateralism: The Trilateral Commission and Elite Planning for World Management, (Boston: South End Press, 1980).

- Leslie Sklair, Assembling for Development: The Maquila Industry in Mexico and the United States, (London: Routledge, 1989).

- Fred Block et al., (eds.), The Mean Season, (New York: Pantheon, 1987); Thomas B. Edsall, The New Politics of Inequality, (New York: WW Norton, 1985).

- Greta R. Krippner, “The Financialization of the American Economy,” Socioeconomic Review, Vol. 3, No. 2 (2005), pp. 173-208.

- Inderjeet Parmar et al., (eds.), “Elites and American Power,” A Special Issue of International Politics, (forthcoming 2017).

- Thomas Piketty, The Economics of Inequality, (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2015).

- Martin Gilens, Affluence and Influence: Economic Inequality and Political Power in America, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012).

- Tim Haynes, “Domenech: Trump and Sanders Represent a ‘Beta Test’ of a ‘New Political Realignment’,” Real Clear Politics, (February 29, 2016), retrieved June 9, 2017 from https://www.realclearpolitics.com/video/2016/02/29/ben_

domenech_trump_and_sanders_represent_beta_tests_of_a_new_political_realignment.html. - Christopher Lasch, The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy, (New York: WW Norton, 1996).

- Zinn, On History.