Introduction

When the historical development of the European integration process is analyzed, it may be observed that the United Kingdom (UK) has long maintained a skeptical and anxious political attitude and behavior toward the issue of transnationalism. While Germany was in ‘year zero’ in 1945 following the Second World War (WWII), France and the three Benelux countries, aiming for economic modernization to overcome their distrust of Germany, focused on attempts to fix the continent’s ill-fortune. The UK preferred to remain indifferent to the integration proposals with which it was presented, as it prioritized its relations with the United States and the Commonwealth of Nations, and considered itself a global power. One of the reasons for this isolationism is that the UK, which was at the peak of its power and prestige following WWII, is well above European standards in economic and military terms. In other words, according to England, the sharing of sovereignty is not for the victorious British, but it is a policy behavior according to the lost Continents.1 European integration, which many British politicians considered unlikely to succeed, was only of symbolic significance outside of free trade issues. As a matter of fact, such a federation requiring the sacrifice of independence was considered a project in which the British could never be involved.2

The UK, which sometimes characterizes its attitude and behavior toward advanced integration efforts in Europe as indifferent and sometimes as devotion, established the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), despite the fact that this organization is less economically advantageous compared to the European Communities (EC); only one year after its establishment, it became the first EFTA country to apply for EC membership.

Considering the periods after it became an EU member, the United Kingdom –which was once the empire on which the sun never set– mostly adopted an obstructive and contrarian attitude in the processes toward expanding the Community policies and establishing the Community as a supranational structure by increasing the powers of decision-making bodies. For example, Britain, the architect of the famous budget wars that left their mark on the history of the EC, did not hesitate to present a member profile that always had more difficulty in acting jointly in many areas, especially monetary union, harmony, and social policies, foreign policy, and security.

It is pertinent that the UK’s decision to leave the European Union as of June 21, 2016, is positioned in the context of the history mentioned above. One striking point here is that the decision to leave the EU was not prevented in the referendum, although different opinions were shared with the public within the framework of transparency and Britain once again demonstrated its contrarian style, similar to the past. As a matter of fact, the UK maintained its reputation for being the first country to decide to leave the European Union by a vote of only 51.9 percent to 48.1 percent.

Since the referendum in June 2016, Brexit has undoubtedly occupied the EU agenda more than anything else. The Brexit process, which officially began on March 29, 2017, with the implementation of Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU), was postponed twice in approximately 34 months, resulting in three government changes and the resignation of two prime ministers and many bureaucrats.3 Finally, as of January 31, 2020, the UK became the first country to officially leave the European Union. The process did not end with this departure, however, and it was decided to continue negotiations until the end of 2020, in order to reach a comprehensive agreement that would regulate future relations between the parties. In order to minimize the potential risk factors for the parties during the 11-month transition period, the UK remained in the EU Single Market and Customs Union while continuing trade dialogues with different countries and with the EU. Turkey is one of those countries. With the end of the transition period granted to the UK, it was announced on December 24, 2020, that an agreement had been reached between the parties. Immediately after this, a free trade agreement (FTA) was signed between Turkey and the UK on December 29, 2020.

The UK maintained its reputation for being the first country to decide to leave the European Union by a vote of only 51.9 percent to 48.1 percent

It would be easy to perceive that the future relations between Turkey and the UK are a crucial issue, considering the fact that the UK, which left the Customs Union by leaving the European Union, is one of the three largest export markets for Turkey. With the completion of the transition period as of December 31, 2020, the rights of Turkish nationals to take employment as workers in businesses in the UK under the Ankara Agreement ended as well.4

The EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement within the Framework of Expectations for Brexit

Following the Brexit referendum held in June 2016, different options regarding the planned trade agreement between the UK and the EU were repeatedly mentioned. The main options were based on existing arrangements between the EU and countries such as Norway, Turkey, Switzerland, Ukraine, and Canada, while the option of leaving the EU with ‘no deal’ remained in place.5 It is understood from the official statement made by the UK Government right after the approval of the Withdrawal Agreement by the European Union that a decision had already been made among the topical models between the parties. The UK Prime Minister Johnson’s request, as discussed below, was reflected in the public opinion polls frequently used in the country during the Brexit process.

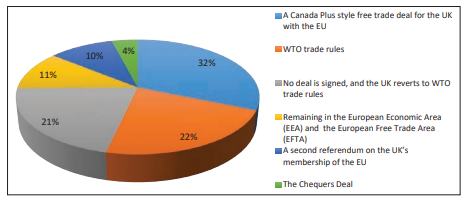

Graph 1: A Survey for the EU-UK Trade Agreement

Source: What UK Thinks, 20186

For example, in a survey conducted in the UK between October 8-10, 2018, the most common answer to the question “What is your preferred option for the UK’s future relationship with the EU?” was “Canada Plus style free trade deal.”

The statement sent by Prime Minister Johnson to the UK Parliament on February 3, 2020, expressed the desire for a deal reflecting the international best practices set forth in the FTAs and already accepted by the EU and one that could be developed when necessary. It was stated that this agreement should include full free trade between the UK and the EU with no tariffs, fees, charges, or quantitative restrictions, and trade-in services that go beyond standard commitments to cover a wide range of key areas, particularly professional services, and commercial services. According to Johnson’s statement, the desired EU-UK trade agreement should cover four main subjects: (i) a free trade agreement, (ii) an agreement on fisheries, (iii) an agreement on internal security cooperation, and (iv) other areas of cooperation.7

In his speech addressed to the public after submitting this text to the Parliament, the Prime Minister clearly stated that he was in favor of an FTA similar to the one between the EU and Canada. However, EU officials pointed out that the UK and Canada are not comparable countries. Indeed, looking at the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), which eliminates 98 percent of the customs tariffs between Canada and the EU, it may be observed that the negotiations took about five years. In addition, it covers many areas, such as removing technical barriers in mutual trade, the best access to public procurement, encouraging investments, geographical indications, facilitating trade visits, and mutual recognition of professional qualifications from architects to crane operators.8

Moreover, due to the COVID-19 pandemic that started in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, before spreading rapidly throughout European countries and causing many deaths, the negotiations did not take place within the predetermined schedule and face-to-face, which was another factor indicating that the expectations would not be fully met.

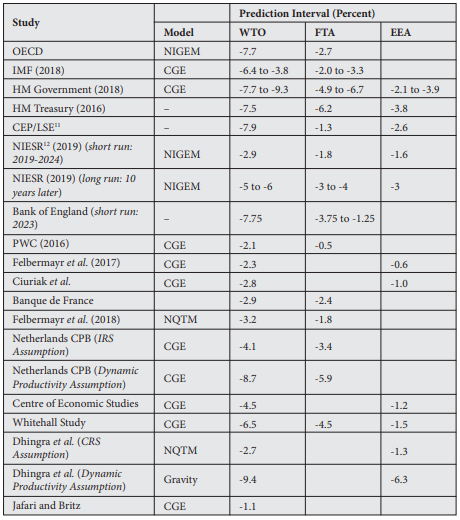

On the other hand, while nearly all the projections regarding the final situation to be reached in the trade negotiations at the end of the transition period pointed to the negative consequences of both the World Trade Organization (WTO) and FTA options (Table 1), additionally the UK that refused to exercise the right to extend the process against the EU, which is much better-equipped in the negotiations, always exhibited a calm profile during the entire process. This attitude has raised questions of imperial arrogance on the part of the UK.

At last, it was announced on December 24, 2020, one day before Christmas, that an agreement had been reached, just six days before the completion of the transition period following negotiations that had lasted for almost a year.

While the deal was described by EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen as “a fair, balanced, right, and responsible step for both parties,”9 Prime Minister Boris Johnson said that they [the UK] had taken back control of their money, their borders, their laws, and their waters and that the deal in question brought a newfound certainty and stability in their relations. Saying that he was very pleased to have completed the trade deal worth £660 billion, the biggest yet, Johnson also once again likened the deal to CETA between the UK and the EU.10

With the agreement applied provisionally as of January 1, 2021, the most tangible benefit for the UK is that it has taken back its own sovereignty again

The agreement, which was signed at a time when the economic and social impacts caused by the COVID-19 pandemic were difficult to cope with and a time of despair in terms of time constraints, is relatively positive compared to never being signed at all. As can be seen from the table below, almost all of the studies modeling the general and long-term economic effects of Brexit on the UK economy predicted a GDP change between -1.5 percent and -18 percent for the WTO scenario, while the models focusing on the limited effect set and so-called static position predicted the GDP and welfare effects of the same scenario as ranging from -1.5 percent to -4.9 percent. With this deal, the risk of trading goods and components with WTO tariffs or quotas is avoided. Therefore, the agreement between the parties is, of course, more profitable for both the UK and its trade partners, as well as EU countries (particularly Germany, Belgium, Spain, and the Netherlands), compared to the WTO tariffs that would have been in effect in the absence of an agreement between the parties.

Table 1: Forecasts Regarding Brexit’s Impacts on UK’s Economy

Source: “Brexit and OBR’s Forecasts,” 2018; Harari, 2018; Hantzsche and Young, 201913

The agreement titled the Trade and Cooperation Agreement ‘draft’ is rather voluminous, with a body text of 420 pages and a full text of approximately 1,300 pages. Contrary to the aforementioned objectives stated by Boris Johnson, total freedom has not been achieved in areas other than merchandise trade. The EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement consists of the following:

- Free Trade Agreement: First, it provides zero tariffs and zero quotas on all goods that comply with the appropriate rules of origin. Whereas the Agreement includes provisions to support trade in services, priority sectors targeted by the UK have been kept closed to mutual service access. These sectors are determined under Title II: (i) air services or related services in support of air services, (ii) audio-visual services, (iii) national maritime cabotage, and (iv) inland waterways transport.14

Additionally, the treaty commits to ensuring a level playing field by maintaining high levels of protection in areas such as environmental protection, the fight against climate change and carbon pricing, social and labor rights, tax transparency, and state aid, with effective, domestic enforcement, a binding dispute settlement mechanism and the possibility for both parties to take remedial measures. Likewise, it is among the positive elements that it includes modern legislative techniques, such as sharing best practices in risk management techniques, including information exchange. The agreement also enables the UK’s continued participation in a number of flagship EU programs for the period 2021-2027 (subject to a financial contribution by the UK to the EU budget), such as Horizon Europe.15

From a different viewpoint, the deal actually exhibits to current and potential members that leaving the EU, which has been aiming to guard its image and global standing after Brexit, is not an easy or lucrative process

On the other hand, the agreement includes no professional recognition other than providing mutual recognition of the Authorized Economic Operator (security and safety) schemes to secure and facilitate trade. Agreements will be negotiated to allow for an improved mechanism to be agreed upon in the future on a profession-by-profession basis. While short-term visits are not subject to visa application, it has been accepted that this right will not apply to third-country nationals living in the territories of the parties. One of the other important topics is road transport; haulers moving goods between the UK and EU will continue to do so without new permit requirements.16

- Close Partnership on Citizens’ Security: The Agreement ensures streamlined cooperation between the national police and judicial authorities, particularly for the fight against and prosecution of cross-border crime and terrorism.17

- Horizontal Agreement on Governance: The agreement, which contains provisions on the implementation and monitoring of the agreement, establishes a Joint Partnership Council.18

With the agreement applied provisionally as of January 1, 2021, the most tangible benefit for the UK is that it has taken back its own sovereignty again.19 The UK can now set its own rules in areas such as environmental standards, labor law, and state aid, etc. The main objective put forward in the request to leave the EU was thus fulfilled. However, this acquisition has already seemed to bring new responsibilities and has proven much more burdensome than was perhaps anticipated, particularly in terms of trade in goods, due to the fact that the UK formally left the EU customs union and single market. Although there will not be any tariffs or restrictive quotas imposed, there will be a whole series of new customs and regulatory checks, including rules of origin and stringent local content requirements. Although this is, of course, the kind of problem that can be overcome by the giant staff known to be recruited by the UK government in relevant fields, the profit-loss cost of this process will emerge over time. The agreement will also lead to the end of freedom of movement and the reintroduction of temporary visas for work-related purposes. Some sectors, including those in financial services and energy, are subject to future regulatory decisions, adding to the uncertainty. Even more importantly, however, is the likely negative effect on trade in services, a field in which the UK has a comparative advantage since there will no longer be automatic recognition of professional qualifications and licenses.20

Services including the retail sector, the financial sector, the public sector, business administration, leisure, and cultural activities are the largest part of the UK’s economy; in 2019, they accounted for 79 percent of the output, production for 13 percent, construction for 7 percent, and agriculture for 1 percent.21 Manufacturing is part of the wider production sector and contributed 9.7 percent to the country’s GDP.22 Moreover, since the UK leaves the European Court of Justice and certain policy areas such as the EU State Aid Regime, more complex and costly days await bilateral relations not only in trade but also in non-trade areas, at least in the short run.

From a different viewpoint, the deal actually exhibits to current and potential members that leaving the EU, which has been aiming to guard its image and global standing after Brexit, is not an easy or lucrative process. Furthermore, in the field of fisheries, which is one of the issues that obstructed negotiations, the fact that the UK has given fishing compromises to the EU countries in its territorial waters for up to five and a half years can be considered a positive development for EU countries.

Relations between Turkey and the UK have a very reliable and strong structure, not only in foreign trade but also in foreign direct investment and tourism

The Turkey-UK Free Trade Agreement

In parallel with the start of the negotiations between the EU and the UK on March 2, 2020, the dialogue to reach a free trade deal between Turkey and the UK began as well. Judith Slater, former Consul General of the UK in İstanbul and also Undersecretary of Trade of Eastern Europe and the Central Asia Network, expressed that the countries of the highest priority to make an agreement with were the U.S., New Zealand, Japan, and Turkey. In an interview she gave to the Anadolu Agency, the Consul General defined the areas open to further cooperation, especially in technology, defense and security, manufacturing, and health services.23 This process continued within the bilateral trade working group established between the two countries since 2016; according to information provided by the Ministry of Trade, five working group meetings and more than fifty video conferences were held during this period. As a matter of fact, just five days after the announcement of the trade deal between the EU and the UK, FTA was signed between Turkey and the UK. The agreement was applied as of January 1, 2021, and entered into force on April 20, 2021.

There were undoubtedly right reasons for Turkey to be in such a hurry to sign the agreement, as the UK, which has traditionally been one of Turkey’s most important trade partners, is also one of the few developed countries with which Turkey has a foreign trade surplus. Relations between Turkey and the UK have a very reliable and strong structure, not only in foreign trade but also in foreign direct investment and tourism.

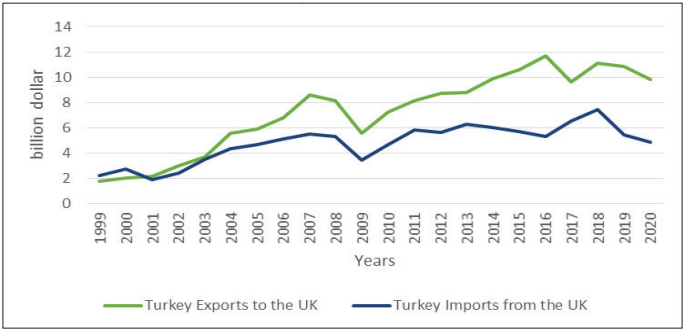

At this point, it is appropriate to mention an important study in order to understand the vehemence and degree of urgency of the situation for Turkey. A study published by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development clearly indicated that Turkey would be the second most negatively affected partner of the UK after the EU in the event of a breakdown in trade negotiations between the EU and the UK. According to the calculations made in the aforementioned study, Turkey, which held access to the UK market through the Customs Union and Pan Euro-Med, would have faced a change of approximately 3.5 percent in tariffs in the case of nonagreement as a result of the trade negotiations between the EU and the UK. This would have meant a loss of approximately 24 percent in Turkey’s total exports to the UK.25

Graph 2: Turkey Trade in Goods with the UK

Source: Turkish Statistical Institute24

As stated by Turkish former Minister of Trade Ruhsar Pekcan in a speech at the signing ceremony, in the absence of a deal, approximately 75 percent of Turkish exports to the UK (notably in the automotive, electric and electronics, textile and raw materials, and apparel sectors) would have subjected to tariffs, corresponding to losses of some $2.4 billion.26

When the agreement is examined, it is seen that it preserves the concessions in the goods and agricultural products belonging to the Customs Union, although it does not include any ambitious and significant areas such as services, investments, and public procurement. However, the rules of origin will be applied instead of the movement certificates (A.TR, EUR.1, and EUR-MED) due to the key component of an FTA. In contradistinction to the previous period, in the new regime, the document to be used to prove the origin of the goods that will be subject to preferential trade within the scope of the FTA is a ‘certificate of origin’ that all exporters can find on their own on an invoice or a relevant commercial document, and no other document will be used for this purpose.27 Thereby loss of time and increase of cost will be prevented in trading operations since there will be no need for approval by an authority, as had been the case with the movement certificates issued previously by professional organizations.

With the agreements signed after Brexit, Turkey and the UK have left their comfort zones; one as the result of a referendum and the other completely involuntarily

One subject that must be addressed here is cumulation. At first, the rules of origin of the agreement between the UK and Turkey reflected the updated Pan-Euro-Mediterranean cumulation, which was a free trade area system based on the cross-cumulation of origin, but now the type of cumulation between parties is full cumulation with a regulation amendment, which is valid as of April 14, 2021.28 Because cross-cumulation had the potential to create remarkable troubles for Turkey’s foreign trade, this revision of the rules in question in parallel with the EU-UK agreement is rather crucial. Because the mentioned type of cumulation meant a limit not exceeding 50 percent for inputs originating from third countries. Compared to other types, full cumulation is the most flexible type of cumulation, since it allows cumulating origin-counting processing added across the FTA territory even when the initial input did not originate in FTA territory.29

Lastly, both countries have committed to extending and deepening the agreement, and so the agreement provides the basis for a more ambitious trade relationship between the UK and Turkey in the future, as stated by International Trade Secretary Liz Truss.30 The agreement contains a review clause that requires the two nations to reconvene within the next two years to discuss expanding the deal further to include services (including digital services) and more liberal regulations on trade and agriculture.31

Conclusion

The EU, which made preferential trade agreements before 2006 where only merchandise trade and some progressive agricultural products trade were valid, focused on the next generation of FTAs following its new strategy, titled “Global Europe: Competing in the World,” dated October 4, 2006. Whereas the EU concluded new-generation FTAs with Canada; Central American countries (Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama), Japan, Peru-Colombia-Ecuador, and South Korea, it has also established Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Areas with Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia. However, it is not difficult to notice that the agreement between the EU and the UK is shallower than the agreements mentioned above.

As is known, deep economic integrations cover a wide range of titles beyond tariffs, such as services, investment, public procurement, and competition policy; in addition to these, they cover mutual recognition of professional qualifications, intellectual property protection, renewable energy, green transformation, education, and training, innovation policies, artificial intelligence, etc., which are considered policies belonging to the 21st century.32 Undoubtedly, taking into account the reality that this is a separation agreement, it is natural that it will not merely be positive and enthusiastic in all points for either of the parties.

Looking at both agreements, the one between the EU and the UK and the one between the UK and Turkey, one can find that both of these are the first step of a new negotiation process to reach a deeper integration and that both have an uncertain schedule because neither of them address content in areas such as services (including digital and financial services), investment, public procurement, green transformation, artificial intelligence, renewable energy, and beyond. Of course, if no agreement had been made, many important sectors would have been subject to customs tax.

As a matter of fact, with the agreements signed after Brexit, Turkey and the UK have left their comfort zones; one as the result of a referendum and the other completely involuntarily. Of course, there will be difficulties at least in the short run, since their economic integration models have been changed; however, these are not insurmountable. From the viewpoint of Turkey, which is eager to maintain its position as a candidate country despite all the problems and the politicization of the full membership process, Brexit may actually be considered a different and creative challenge that brings with it development potential. The next dialogues after the FTA between the UK and Turkey can guide the negotiations of Customs Union modernization and open up opportunities for new potential trade agreements with other third-party countries by providing great technical knowledge and experience for Turkey. The next process will be shaped according to the steps to be taken by the countries and the adaptation response and the level of flexibility of the new order.

Endnotes

1. Desmond Dinan, Avrupa Birliği Tarihi, translated by Hale Akay, (İstanbul: Kitap Yayınevi, 2008).

2. Alex Warleigh, European Union: The Basics, (London: Routledge, 2008), pp. 16-17.

3. While the final separation would have occurred on March 29, 2019, it was postponed first to October 31, 2019, and then to January 31, 2020.

4. The Ankara Agreement could allow a Turkish national to attain permanent residence in the UK after a certain period of time.

5. “The Options for the UK’s Trading Relationship With the EU,” Institute for Government, (March 2018), retrieved from https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainers/options-uk-

trading-relationship-eu.

6. “What Is Your Preferred Option for the UK’s Future Relationship with the EU?” What UK Thinks, (2018), retrieved January 16, 2021, from https://whatukthinks.org/eu/questions/what-is-your-preferred-option-for-the-uks-future-relationship-with-the-eu/.

7. “The Written Statement for Parliament: The Future Relationship between the UK and the EU,” HM Government, (2020), retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/the-future-relationship-between-the-uk-and-the-eu.

8. “One Year on EU-Canada Trade Agreement Delivers Positive Results,” European Commission, (2018), retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/press/index.cfm?id=1907.

9. “Remarks by President Ursula Von Der Leyen at the Press Conference on the Outcome of the EU-UK Negotiations,” European Commission, (2020), retrieved January 1, 2020, from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_20_2534.

10. “Prime Minister’s Statement on EU Negotiations,” HM Government, (2020), retrieved January 1, 2021, from https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/prime-ministers-statement-on-eu-negotiations-24-december-2020.

11. The Centre of Economic Performance at the London School of Economics.

12. The National Institute of Economic and Social Research is a London-based institution.

13. “Brexit and the OBR’s Forecasts,” Office for Budget Responsibility, (October 2018), retrieved from https://obr.uk/forecasts-in-depth/the-economy-forecast/brexit-analysis/#assumptions; Daniel Harari, “Brexit Deals: Economic Analyses,” House of Commons Library, No. 8451, (December 4, 2018), retrieved from https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-8451/CBP-8451.pdf, p. 23; “2019 UK General Election Briefing: The Economic and Fiscal Impact of Brexit,” The National Institute of Economic and Social Research, (2019), retrieved from https://www.niesr.ac.uk/sites/default/files/publications/NIESR%20Election%20Briefing%20-%20The%20Economic%20and%20Fiscal%20Impact%20of%20Brexit%20-%20FINAL.pdf, p. 4.

14. “The EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement,” EUR-Lex, (December 12, 2020), retrieved from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:22020A1231(01)&from=EN, 88-89.

15. “EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement: Protecting European Interests, Ensuring Fair Competition, and Continued Cooperation in Areas of Mutual Interest,” European Commission, (2020), retrieved January 6, 2021, from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_2531.

16. William Barns-Graham, “10 Key Things to Know about the UK-EU Free Trade Agreement,” Institute of Export and International Trade, (2020), retrieved January 14, 2021, from https://www.export.org.uk/news/545492/10-key-things-to-know-about-the-UK-EU-Free-Trade-Agreement-.htm.

17. “The EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement,” European Commission, (April 30, 2021), retrieved from, https://ec.europa/eu/info/relations-united-kingdom/eu-uk-trade-and-coertion-agreement_en.

18. “The EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement,” pp. 23-24.

19. EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement entered into force on May 2021.

20. Matthias Matthijs, “What’s in the EU-UK Brexit Deal,” Council on Foreign Relations, (2020), retrieved January 10, 2021, from https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/whats-eu-uk-brexit-deal.

21. Lorna Booth, “Components of GDP: Key Economic Indicators,” House of Commons Library, (2021), retrieved January 23, 2021, from https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn05206/.

22. Georgina Hutton, “Manufacturing: Key Economic Indicators,” House of Commons Library, (2021), retrieved January 23, 2021, from https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn05206/.

23. “Birleşik Krallık İstanbul Başkonsolosu Slanter: Türkiye ile 2020’de STA Yapmakta Kararlıyız,” Anadolu Agency, (2021), retrieved February 22, 2021, from https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/ekonomi/birlesik-krallik-istanbul-baskonsolosu-slater-turkiye-ile-2020de-sta-yapmakta-kararliyiz/1740399.

24. “Turkey Trade in Goods with the UK,” Turkish Statistical Institute, retrieved from https://biruni.tuik.gov.tr/disticaretapp/menu.zul.

25. “Brexit Implications for Developing Countries,” United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, (2019), retrieved from https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/ser-rp-2019d3_en.pdf.

26. “Turkey, UK Sign Historic Free Trade Agreement,” Anadolu Agency, (2020), retrieved January 8, 2021, from https://www.aa.com.tr/en/economy/turkey-uk-sign-historic-free-trade-agreement/2092362.

27. “Brexit Süreci ve Yeni Dönemde Birleşik Krallık ile Ticarete İlişkin Sıkça Sorulan Sorular,” Rebuplic of Turkey Ministry of Trade, retrieved January 8, 2021, from https://ticaret.gov.tr/dis-iliskiler/brexit-ve-birlesik-krallik-sta.

28. The mentioned regulation amendment entered into force on May 30, 2021, to be effective as of April 14, 2021. Please see, https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2021/05/20210530-3.htm.

29. “Accumulation/Cumulation,” Rules of Origin Facilitator/International Trade Center, retrieved February 10, 2021, from https://findrulesoforigin.org/en/glossary?uid=accum&returnto=gloscen.

30. “UK Signs Free Trade Agreement With Turkey,” The Guardian, (December 29, 2020), retrieved January 12, 2021, from https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2020/dec/29/uk-signs-free-trade-agreement-with-turkey.

31. “UK and Turkey to Sign Free Trade Deal this Week,” (2020), Financial Times, retrieved January 12, 2021, from https://www.ft.com/content/f7a8a311-c149-4454-92f3-905df1e72e86.

32. For the coverage and the depth of the preferential trade agreements examined within the classification of WTO+ and WTO-X, comprised of 52 policy areas, please see, “World Trade Report 2011: Anatomy of Preferential Trade Agreements,” World Trade Organization, (2011), retrieved from https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/anrep_e/wtr11-2d_e.pdf, pp. 122-163.