Introduction

In more than thirty years of reform and implementation of open economy policies, great changes have taken place in China. With the country’s high engagement with the world, it became obvious that China did not isolate itself from the global developments. The rapid growth of China’s economy and the country’s growing ties with the rest of the world necessitate the development of new concepts and approaches in the Chinese diplomacy. On January 3, 1992, the Republic of Kazakhstan set diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The two countries share a border of 1,700 km and their relationship has developed rapidly since 1997, in connection with the growing of the economic ties. According to the Treaty on Good-Neighborliness, Friendship and Cooperation signed on December 23, 2002, the states develop the long-term peaceful and beneficial “win-win” cooperation. Most of the routes from China to Europe pass through Kazakhstan’s broad territory, located strategically on the crossroads between Europe and Asia. As China is expanding its economic outreach to Europe, Kazakhstan wants to benefit beyond transit fees as it is trying to break away from oil dependence.

This paper is organized in five different parts. First, it discusses current concepts and approaches of the Chinese diplomacy within the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and New Silk Road Economic Belt (NSREB). The second part covers China’s policy on strengthening the stability and security at the neighboring Central Asian region through the SCO. Later it discusses the attempts of economic and humanitarian cooperation within the SCO and newly introduced economic projects within the NSREB as another away for substantive regional integration. The last two sections focus on the cultural dimension of China’s New Silk Road Initiative and its implementation in Kazakhstan, and analyze public perception of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in Kazakhstan according to the survey and Kazakhstani mass media.

Current Chinese Concepts and Approaches of the SCO and NSREB Diplomacy

China’s emerging role in the international arena triggers a change in the current international political environment and causes further rebalancing of the multipolar system. Therefore, strengthening multilateral cooperation with the other regional powers and international organizations provides a suitable atmosphere for development of China’s New Diplomacy. The basis of China’s New Diplomacy is formed by the New Security Concept, the New Development Approach, and the New Civilization Outlook, which were introduced in the early 2000s. China’s New Diplomacy has first been visible in China’s diplomacy towards the Asian region, because the neighboring countries have always been crucial for Beijing to create a favorable and stable international environment. The New Security Concept encourages nations to build trust through consultations and to seek national security by means of multilateral coordination. It emphasizes: (i) multilateral ties, which stress interdependence among nations in terms of security; (ii) cooperation, which replaces confrontation as the effective route to security; (iii) comprehensiveness of security, which is not only confined to military and political fields alone, but also includes economic, technical, social and environmental fields; (iv) institutional construction, as the legitimate road to security.1 The New Security Concept rejects power politics and the Cold War thinking. Proposed at the forum of the Central Committee of China’s Communist Party in March 2004, by the President Hu Jintao, the New Development Approach stated that all countries should strive to achieve mutual benefit and “win-win” situations in their pursuit of development. Moreover, the New Civilization Outlook as a part of Hu Jingtao’s concept of the Harmonious World encourages intercivilization dialogue and aims at building a harmonious world on the basis of equality.2 The key idea of the concept is that each civilization has the inalienable right to choose its own and independent development path, which is suitable for its own conditions. On the other hand, the SCO, which is a successor of the Shanghai Five Mechanism encouraged by Beijing in 1996 in order to resolve the border issues among China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, initiated the practice of China’s New Security Concept. Established in 2001, the SCO requires member states to develop state-to-state relationships based on partnerships rather than alliances. The SCO hints at new regional cooperation model under which member states coordinate their actions, however there are no treaty-based obligations in the military field. After settling border disputes, the SCO members promoted cooperation in fighting terrorism, separatism and extremism in line with China’s New Security Concept.

In keeping with the principles of the New Civilization Outlook such as non-alignment and non-confrontation, the SCO respects the traditions of every member state and their right to independently choose their own development paths

In keeping with the principles of the New Civilization Outlook such as non-alignment and non-confrontation, the SCO respects the traditions of every member state and their right to independently choose their own development paths. The above-mentioned ideals were entrenched in the Charter of the Organization signed in 2002, as well as in the Declaration on the 5th anniversary of the SCO inked in 2006. Since the SCO has gradually moved to explore the possibilities of economic collaboration along with security cooperation, the New Development Approach is also well expressed in the plans and actions of the organization. In 2003, the program of multilateral trade and economic cooperation among the SCO member states was signed defining the basic goals of economic cooperation within the framework of the organization. Thus, the process of establishment of the SCO started with the shaping of the Shanghai Spirit, which was first announced by the former President Jiang Zemin at the Summit of the Shanghai Five heads of state in Dushanbe in 2000. This process fully corresponds with China’s New Diplomacy principals. The SCO was developed and institutionalized within the framework of Hu Jingtao’s Harmonious World Concept. Therefore, establishment of the SCO could be considered as the first Chinese experience on the implementation of China’s New Diplomacy. The transformation of the Shanghai Initiative from the Shanghai Five Mechanism to the SCO corresponds with the transformation of China’s international diplomacy. By initiating and developing the SCO, China started focusing on multilateral relations with the Central Asian countries rather than on bilateral relations. It should be admitted that China is still in the process of developing comprehensive and multidimensional approaches of its New Diplomacy. However, there is no doubt that with its New Diplomacy, China will aim to guide the SCO and NSREB member states in their political and economic activities.

Security First: The SCO

The SCO now has China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, India and Pakistan as its full members, with Afghanistan, Belarus, Iran and Mongolia as observers, and Armenia, Azerbaijan, Cambodia, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Turkey as dialogue partners. Nowadays, the SCO brings together 18 states, which are inhabited by over 3 billion people or over 45 percent of the world population.3 In 2015, the GDP of the SCO member states amounted to over $21 trillion, accounting for 27.1 percent of the world’s total.4 The official founding declaration asserted that the main objective of the organization was to combat the so-called three evil forces: international terrorism, ethnic separatism and religious extremism. The organization has been interpreted in a variety of ways since its inception. Some analysts agree with the views of the governments of the SCO member states that the organization is primarily focused on regional security problems.5 Many Chinese analysts as Yu Jianhua, Director of the Institute of Eurasian Studies of the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences (SASS), express the same view: the SCO is a regional organization of non-traditional security.6 Western interpretations are quite different, as they argue that the SCO constituted a joint effort by a group of authoritarian states to defend themselves against regime change in the face of a regional democratic trend.7 Most approaches explain the SCO geopolitical activities in terms of balance of powers. The SCO was called the “NATO of the East”8 and “New Warsaw Pact,”9 this military approach concerned with geopolitical balancing issues in Central Asia. The SCO enables its member states to pursue diplomatic, security, economic, and soft power goals but remains primarily an institution focused on security. However, although SCO leaders agree that the organization should defend its member governments against terrorist or separatist threats, they have deadlocked over whether to respond collectively to serious but nonviolent domestic challenges such as mass protests. With only two standing organs (the RATS and Secretariat), the SCO is much less developed than other regional security organizations. It could profitably develop its crisis management capabilities, whose weakness perhaps accounted for the organization’s paralysis during the July 2010 crisis in Kyrgyzstan.10 Richard Weitz and Daniel Miller based on the theory of integration and regional cooperation considers that the SCO has actually failed to realize security goals, dismissing the SCO as a “security failure” and a “fading star.”11

The program of cooperation on security issues began shortly after establishing of the SCO. At that period it was very important for China to prevent the foreign intervention into the Central Asian states policy and security, as well to avoid support for ETIM by the other newly independent Central Asian Turkic countries

Most Chinese experts as Chien Chung, Pan Guang and Jing-Dong Yuan agree that this regional organization is largely a Chinese initiative and that China plays a leading role in the SCO process.12 China attempted to enter and to manage this region via a multilateral approach and it is using the SCO for implementation of the “Beijing Consensus” in Central Asia. The SCO has gradually become the main mechanism or guide for China’s policy in Central Asia. Along with the Central Asian countries, the organization includes Russia, which allows to significantly mitigate the perception of China in the Central Asian region as a threat. Also, the SCO provides a good framework for China to cooperate closely in combating terrorism, extremism, separatism and various other cross-border criminal forces. The primary target of the Chinese anti-terrorism campaign is the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), which advocates for the independence of Xinjiang. From the Chinese perspective, in the framework of the SCO it is of particular importance for China to be able to count on the support of the other nine member and observer states in its campaign against the ETIM. Moreover, China has also been able to draw support from the SCO partners in its efforts to frustrate other conventional or non-conventional security threats and to eliminate or to ease the external factors of disruption to China’s stability and development.13 By 2001, when the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation was formed, Chinese leaders were fully convinced that multilateral regional organizations were significant mechanisms for China to articulate its interests, strengthen its influence, cultivate its soft power, and promote multipolarity. In less than a decade, China was transformed from a passive, defensive participant to an active organizer with a well-defined agenda and strategy.14 Through the SCO, China is keeping geopolitical balance in the “strategic hinterland” region as well as playing a key role in the establishment of a new structure of regional security process legally. The program of cooperation on security issues began shortly after establishing of the SCO. At that period it was very important for China to prevent the foreign intervention into the Central Asian states policy and security, as well to avoid support for ETIM by the other newly independent Central Asian Turkic countries. In this light, following documents were signed in the SCO framework: The Shanghai Convention on combating terrorism, extremism and separatism (2001), SCO regional anti-terroristic structure (2002), agreement on combating drug trafficking (2004), agreement on joint anti-terrorist activities (2006), treaty of the long-term good neighborly and friendly cooperation among member states of the SCO (2007), agreement on combating trafficking in firearms, ammunition (2008), agreement on cooperation in the field of ensuring international information security (2009); joint declaration on cooperation between the SCO and UN secretariats (2010), provision on the political, diplomatic measures and mechanisms for regulating the situations that endanger security and stability of the region (2012). Also, the Peaceful Mission –joint anti-terroristic military exercises were first time kicked off within the SCO framework in 2002. The member-state military units practiced a joint anti-terrorist operation in the SCO territory annually. Combat units have worked out actions to confront terrorists on land, at sea and in the air. All these agreements provided legislative base for the SCO common security space and adopted political and military measures, building an unpredictable cooperative and stronger relationships within the regional community and through the security cooperation the SCO passed the institutionalization process.

Economy Is Significant

China employs the SCO as a vehicle to expand its influence in its immediate neighborhood where it does not have any solid historical and cultural foundation, as opposed to Russia, which long had Central Asia as a part of Tsarist Russia and later as a part of the Soviet Union for about two hundred years. The economic and humanitarian cooperation within the SCO was evaluated by China along with the security issues. However, Beijing started to seek economic collaboration within the SCO after the main border, defense and security questions were solved among the member-states. China held great hopes for the ability of the SCO to organize multilateral economic cooperation. Beijing wanted to use the SCO in order to export its products, labor and capital to the neighboring countries. Thus, Beijing several times proposed the idea of establishing the SCO Free Trade Area (FTA). Following agreements on economic and humanitarian cooperation were signed within the SCO: the program of long-term multilateral economic cooperation (2003), action plan of the program of long-term multilateral economic cooperation (2004), SCO interbank consortium (2005), SCO business council (2006), new action plan on multilateral economic and trade cooperation (2008), emergency assistance agreement (2005), agreement between governments on cooperation in education (2006), agreement between governments on cultural cooperation (2007), agreement between governments on scientific cooperation (2007). Moreover, in order to promote the economic development of the SCO member-states and deepen their economic cooperation, China represented by the President Hu Jintao at the 2005 Astana Summit offered $900 million preferential buyer’s credit loans to the other SCO members. In 2006, the China Import and Export Bank signed preferential buyer’s credit with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan providing $1.2 billion of preferential buyer’s credit in 2007. A decision on allocating another $10 billion governmental loans was announced by the President Hu Jintao at the 2012 Shanghai Summit. According to the Chinese customs statistics, the trade turnover between China and the SCO member-states increased from $12.15 billion in 2001 to $67.47 billion in 2015 showing 6.6 fold increase. According to the Ministry of Commerce of China, in 2003, the amount of the Chinese foreign direct investments (FDI) to the SCO member-states amounted to $59 million reaching $534 million in 2015. Therefore, it could be stated that since the establishment of the SCO, its member-states have become China’s main partners in foreign investment. However, despite these positive developments serious obstacles to further progress in strengthening economic cooperation still remain. To date, high customs tariffs are the main barriers for deepening trade relations among the SCO states. Therefore, in order to minimize the tariff and non-tariff barriers, as well as to facilitate trade and investment in the region, the SCO members put the creation of the FTA on the agenda. Beijing was equally interested in the development of security aspect as well as economic ties. China held great hopes for the ability of the SCO to organize multilateral economic cooperation. Beijing wanted to use the SCO in order to export its products, labor and capital to the neighboring countries. For this purpose China offered a variety of projects: from an introduction of a free trade zone to the establishment of the SCO Development Bank.15 Nevertheless, to date these initiatives have not been fully welcomed by the SCO member states. In 2011 the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) was created by Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan. China put great attention to the process, since the organization limited the access to the markets of these countries creating new tariffs and taxes. Thus, the main Chinese partner in the SCO framework –Russia– has chosen its own way of economic integration with the Central Asian states, re-establishing this type of economic cooperation for the first time since the Soviet Union collapse. The implementation of the EEU project allowed China to develop an effective and beneficial strategy of interaction with a new Eurasian integration association. Thus, Beijing has offered a number of programs on investments into the SCO states from the assets of the organization on a bilateral basis.16

The EEU, a regional organization, initially created with the aim to protect itself from excessive economic influence of China, has changed its direction toward the interface with the Chinese initiative

Other economic projects were not carried out within the framework of the SCO. The crisis of 2014, and the sanctions against Russia considerably damaged the economic situation in Russia and the entire Central Asian region prompting the need for investments. In this light, China immediately suggested the establishment of the Silk Road Fund. All these factors have a positive impact on the fact that China, relying on the SCO as a base platform, put forward a new initiative, the creation of the New Silk Road Economic Belt (NSREB) and the 21st century Marine Silk Road in 2013. At the moment, the initiative is called “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI). Consequently, the EEU, a regional organization, initially created with the aim to protect itself from excessive economic influence of China, has changed its direction toward the interface with the Chinese initiative.17 The Eurasian Economic Commission has formed a list of priority projects that will be implemented by the EEU countries and will support the formation of the NSREB. The projects concern the construction and modernization of roads, the creation of transport and logistics centers, and the development of key transport hubs.18

Taking into account the fact that China has already established the FTA with Pakistan and launched joint research with India in creating the FTA, it could be determined that China has formed some preconditions for the FTA creation within the framework of the SCO

The SCO approved two documents relating the procedure of admitting new members at the Tashkent summit in June 2010: The Rules of Procedure and the Statute on the Order of Admission of New Members to the SCO. The stance reflected in these two documents mainly represents a passive Chinese response to the enthusiastic membership requests expressed by some states. It, by no means, implies that the SCO members have a specific enlargement plan in mind, let alone a consensus. A combination of new members and a determination to make the organization a genuinely important and influential bloc is likely to ensure further development and expansion of the SCO.19 The ambition to create a truly dominant organization free of any Western influence may become a reality in the near future. It is quite easy to set up formal multilateral organization. However, whether this organization can or cannot have a real effect on international relations is another matter. In this institutional dimension, China has more freedom to play, since its partners do not treat the issue as a priority. Russia and the Central Asian states understand the utility that the SCO provides to them. This multilateral institution is also helping China and Russia to regulate their interactions in Central Asia. China will not give up its attempt to play the leading role because it has huge stakes riding on it, including its international reputation and credibility.

Family photo of the SCO, before the 18th meeting of the SCO Council of Heads of States, which was held in China on June 10, 2018. METZEL / TASS via Getty Images

China’s Other Way for Substantive Regional Integration

The establishment of the NSREB has solved an issue of the future enlargement of the SCO membership. China was not generally interested in inviting new members to join the organization because it was more concerned with consolidating security and economic cooperation with the existing members. When commenting on the Regulations on Observer States of the SCO in June 2004, the Secretary General of the SCO, Zhang Deguang, stated that the priority of the SCO was not the enlargement but the more substantial international cooperation and development.20 As summarized by Sanat Kushkumbayev, unless clear parameters of the economic interaction within the framework of the SCO are established, Beijing would not be interested in expanding the SCO membership to include the states of Southeast Asia.21 Based on Russia’s proposal, the SCO leaders passed a resolution on starting the procedures of granting India and Pakistan a full membership in the organization at the 15th SCO summit in Ufa, Russia in 2015. Pakistan applied for a full membership in 2006 and India in 2014. There are enough reasons explaining Pakistan’s enthusiasm to become an SCO member. It has strong political, economic and security motivations. Foreseeing that the SCO membership may further strengthen its ties with China, a longstanding ‘all weather’ ally is equally important.22 On the other hand, China is happy to see its ally as part of the organization. It understands that the admission of Pakistan alone is unacceptable to Russia. Analysts believe that India’s bid to join the SCO is supported by Russia, as Russian policymakers believe that it would be easier to constrain China’s influence on the SCO with India as a full member.23 As for China, it had no reason to welcome a potential competitor into an organization where it played a leading role until the admission of Pakistan. Both India and Pakistan were admitted to the SCO inciting rivalry within the organization. In fact, during the last SCO Summit 2017 held in Astana, Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev stated that the growth of mutual trade in future can contribute to the creation of the SCO FTA, countries can move forward step by step, starting with the study of projects of economic cooperation of their interest. 24 Therefore, taking into account the fact that China has already established the FTA with Pakistan and launched joint research with India in creating the FTA, it could be determined that China has formed some preconditions for the FTA creation within the framework of the SCO.

Despite the fact that originally Central Asia was not among the regions with promising import capacities for Chinese goods, under the NSREB initiative China decided to relocate a number of production facilities to the regional countries

Thus, China was given the opportunity to implement an investment policy that in the future would apparently lead to economic integration. The BRI construction will significantly increase the economic and infrastructural interdependence of the region countries. Moreover, the program correlates with the Chinese “Going Outside” Strategy, which aims to facilitate Chinese outbound investment necessary to maintain economic growth. Speaking at the first Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation, which was held on May 14-15, 2017, in Beijing, the President of Kazakhstan, Nursultan Nazarbayev, noted that the BRI allows the forming of a new geo-economic paradigm, and the countries with a total population of 4.4 billion people will benefit from its successful implementation. According to Nursultan Nazarbayev, the idea of creating a single economic space of “Great Eurasia” gives a sense of purpose, as the Silk Road Economic Belt can advantageously link the platforms of the SCO, the EEU and the European Union into a single regional prosperity area.25 It is obvious that China will use the SCO platform to implement the China-led Eurasian economic integration strategy.

Continental infrastructure development is one of the key goals of the NSREB. China’s rail system has long linked to the Trans-Siberian rail system through northeastern China and Mongolia. In 1990, China added a link between its rail system and the Trans-Siberian system via Kazakhstan. China calls its uninterrupted rail link between the port city of Lianyungang and Kazakhstan the New Eurasian Land Bridge or the Second Eurasian Continental Bridge. In addition to Kazakhstan, the railways connect with other countries in Central Asia and the Middle East, including Iran. Since the completion of the rail link across the Bosporus under the Marmaray project in October 2013, the New Eurasian Land Bridge has been connecting to Europe via Central and South Asia. During the 12th meeting of Heads of Governments of the SCO member states on November 29, 2013 in Tashkent, the Prime Minister of the State Council of China, Li Keqiang, stated that Lianyungang city, located in the eastern beginning of the new Eurasian Continental Bridge, would give the member states of the SCO an access to logistics services and warehousing.26

Cargo trains have already begun running from China to Iran through the territory of Kazakhstan and Astana is hoping to modernize its own available locomotives and repair 460 miles of rails. The project’s total cost is to amount to $2.7 billion; by making the upgrade, Kazakhstan aims to capture 10 percent of the $600 billion trade volume between China and Europe. The government of Kazakhstan has launched several programs including the “2050 strategy” and the “100 concrete steps” that incorporate Chinese investments and goals for realignment with the BRI. In effect, trade turnover between the two nations has surpassed $20 billion and keeps growing, turning China into Kazakhstan’s major strategic partner. Beijing has also already invested nearly $30 billion in the country’s mining, oil, transport, and agricultural sectors. These investments add to Astana’s own $9 billion stimulus plan for the nation’s modernization. Furthermore, Astana is also constructing “special economic zones” that include the Khorgos “dry port” on the Kazakh-Chinese border. On November 25, 2011, the Kazakh government decided to establish the Khorgos-East Gate logistics center near the Khorgos “special economic zone.”27 Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev and Chinese President Xi Jinping attended the opening ceremony of the first stage of the Kazakhstan logistics terminal in the Lianyungang port on May 19, 2014. The first train carrying 720 tons of wheat from Kazakhstan arrived in the Lianyungang port on February 5, 2017. The first batch of wheat from Kazakhstan arrived in the Lianyungang port by a cargo train and was then shipped to Southeastern Asia, opening a new trade route. Transit cost of Kazakhstan’s trade with East Asia significantly reduced, saving about $72 million per year.28 Chen Zhongwei, the Director of the Chengdu Port and Logistics Office in the southwestern Sichuan province, stated that the bulk of trains from China to Europe pass through the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region and Kazakhstan. In 2016, more than 1,800 trains were sent from China to Europe, and over 500 traveled backwards.29 Thus, through the China-Kazakhstan BRI cooperation, Astana has emphasized its purpose to turn Kazakhstan into the major transport and logistical hub of Eurasia. On the other hand, China diversifies its already significant capacity of trade railways and establishes new continental routes.

That the need to overcome the long embedded divisions and prejudices regarding Chinese growing economic domination over the region, China’s population growth rate and Beijing’s geopolitical ambitions, will be one of the main obstacles for the Silk Road Economic Belt implementation

Despite the fact that originally Central Asia was not among the regions with promising import capacities for Chinese goods, under the NSREB initiative China decided to relocate a number of production facilities to the regional countries. Beijing is interested in developing infrastructure and industry in the neighboring Central Asian countries since it views them as a promising transit corridor connecting China with its main trading partner, the EU. The region can also provide foreign enterprises with cheap labor and opportunities for promoting the Chinese management and business culture. For instance, in 2016, Beijing and Astana adopted a program towards transferring production facilities from China to Kazakhstan. According to the program, 51 investment projects under the Kazakhstani-Chinese industrial and investment cooperation at a total cost of $26.2 billion include both transferring existing industries from China to Kazakhstan and establishing new industries in the country. All the projects are implemented in the processing industry as well as in infrastructure, in particular in metallurgy, oil and gas processing, chemical industry, machine engineering, energy production, consumer industry, agricultural processing, transport and logistics, new technologies and manufacture of consumer goods. New enterprises will be established in almost every region of Kazakhstan, but most of the projects will be implemented in the North Kazakhstan, East Kazakhstan, Almaty and South Kazakhstan regions. Moreover, China’s $40 billion Silk Road Fund agreed to contribute $2 billion to the China-Kazakhstan Joint Foundation “Silk Road,” which is aimed to support capacity building cooperation between China and Kazakhstan and investments in related projects.

New Silk Road, Old Dimension

The most obvious incarnation of revitalization of China’s efforts to strengthen its presence in Eurasia became BRI, which has become one of the most iconic and innovative manifestations of modern trends of economic globalization and regionalization. The Silk Road Initiative suggested by China has become the final stage of the Deng Xiaoping’s ‘hide your strength and bide your time’ strategy implementation. In his speech at Nazarbayev University, Kazakhstan in 2013, Xi Jinping emphasized the fact that the countries of the region are united by strong bilateral relations and shared history. Assuring the Central Asian countries that China would always respect the chosen development path of the other states, Xi Jinping also stated that Beijing had no claim to dominate in the region.

Speaking of the cultural dimension of China’s New Silk Road Initiative it should be mentioned that it is based on the principle of interaction of the nations. According to the fifth cooperation priority of the Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, strengthening the public diplomacy or people-to-people bond includes the following areas: education (10,000 scholarships per year), culture and art, tourism, health care, youth policy, science and technology, and political parties and parliaments cooperation. In fact, Kazakhstan ranks 9th at the top 10 sending countries of total international student enrollment in China. In his article titled “May China-Kazakhstan Relationship Fly High Toward Our Shared Aspirations” published by the leading Kazakh newspaper, Kazakhstanskaya Pravda, ahead of his state visit on June 7-10, 2017 to Kazakhstan, the Chinese President Xi Jinping stated that in 2016 the number of mutual trips of Kazakh and Chinese nationals reached 500,000, while the number of Kazakhstani students studying in China increased to 14,000.30 Thus, China has proposed a geo-cultural strategy for Eurasia, which should provide realization of its economic goals and priorities. Actually, the formation of the geo-cultural framework of the New Silk Road Initiative (NSRI) is just as important for China as the implementation of its economic strategy. China’s cultural vision of the NSRI is based on the assumption that mutual trust and better understanding of each other’s art and culture will definitely enhance international cooperation and make it possible to overcome any deeply entrenched prejudices and suspicions raised from cultural differences. It is quite understandable that the need to overcome the long embedded divisions and prejudices regarding Chinese growing economic domination over the region, China’s population growth rate and Beijing’s geopolitical ambitions, some of which are justified while others are not, will be one of the main obstacles for the Silk Road Economic Belt implementation. Nowadays, the ancient Silk Road is being rebuilt in the form of a transcontinental network of bullet trains, oil and gas pipelines, highways, telecommunication lines and satellites, trade agreements and scientific cooperation. However, the NSREB also needs a cultural dimension. The aforementioned barriers are mostly based on the sinophobia formed in many countries over the world, especially in the ones neighboring China, centuries ago. Therefore, Beijing’s choice to use the concept of the revival of the Silk Road to destroy old and newly formed phobias and stereotypes towards China and people of the Chinese origin was not accidental. The Chinese authorities believe that the New Silk Road Initiative will be successfully implemented in the region due to historical analogies of mutual enrichment of cultures. The cultural dimension of the NSRI played an important role in the creation of the positive perception of the Chinese project. One of the major outcomes of the Chinese strategy aimed at boosting cultural interaction within the framework of the NSREB is the creation of a non-governmental Organization for Cultural Cooperation, “Eurasia–Silk Road.” The agreement on launching of the Organization was reached during the Second Great Silk Road International Cultural Forum, which was held in Moscow on September 14-15, 2015 and organized by the Chinese Foundation of Culture and Arts of Nations, the China’s Silk Road Fund, the Fund of Spiritual Development of people of Kazakhstan and the Intergovernmental Foundation for Humanitarian Cooperation for the Commonwealth of Independent States. The main theme of the Forum was “Developing Partnership: Planning of Joint Projects for Cultural Cooperation.” More than 300 eminent scientists, artists, politicians, businessmen and media representatives from countries along the NSREB and also representatives of the SCO and UNESCO attended the meeting. It also should be mentioned that according to the Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, China will focus on both holding years of culture, arts and film festivals, TV weeks and book fairs in each other’s countries and cooperating on production and translation of high-quality films, radio and TV programs.

Kazakhstan is likely to become the major contributing partner of China in its BRI project, in particular, its continental part –the “Silk Road Economic Belt”

It is obvious that tourism relations between countries along the NSREB should also be enhanced. Beijing is planning to hold tourism promotion weeks and publicity months, to jointly create competitive international tourist routes and products with Silk Road features and to make it more convenient to apply for tourist visas in countries along the route of the New Silk Road Initiative. For instance, Kazakhstan and China have already initiated joint cultural projects such as an international expedition “Thousands Li Along the Silk Road,” which was held in Almaty in 2014, and a walking friendship and cooperation caravan titled “China and Kazakhstan: Tea Culture of the Great Silk Road,” which arrived in Kazakhstan in 2015 and was directed from Xian to ancient trade routes, carrying valuable Deyang treating tea Fuca grown in the Chinese Shaanxi province. Moreover, in order to integrate Chinese culture into the outside world by building the NSRI, China also launched press tour titled “A New Silk Road, A New Dream,” which started in Xi’an, capital of China’s western Shaanxi province and the starting point of the ancient Silk Road, in June 2014. At the time when the initiative was first launched, it caused a great deal of concern and even mistrust in Eurasia. However, it took only two and a half years to develop rather strong support of the NSREB initiative along the countries of the route. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi on May 21, 2016 stated that more than 70 countries and organizations have expressed their support and participation. Meanwhile, 34 countries and international organizations have signed inter-governmental cooperation agreements with China on jointly building the BRI.31 By implementing the NSRI China hopes to spread its cultural values, which could become a “modern fashion” in many countries along the road and in the long-term perspective, could even lead to the formation of the “Chinese Eurasia” or the “sinocentrical” world.

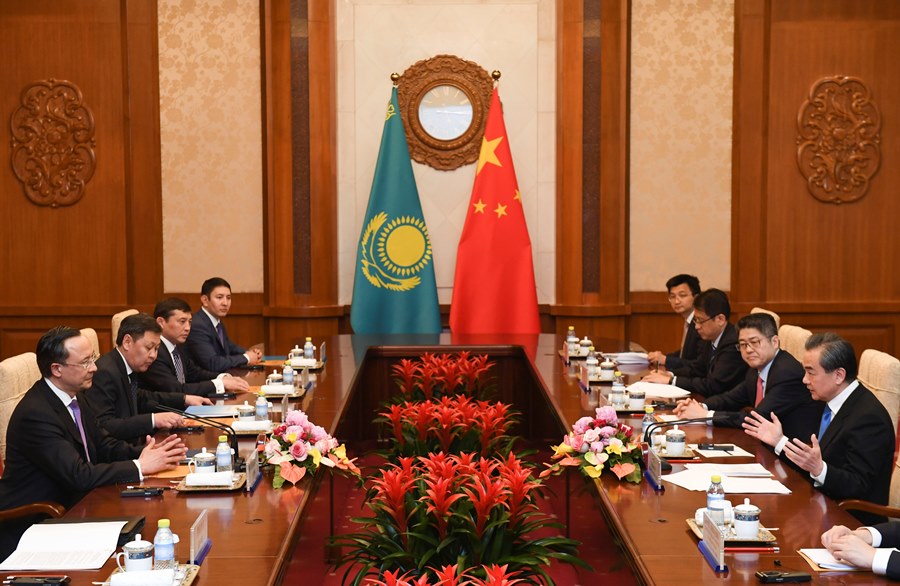

Kazakh FM Abdrakhmanov (L) and Chinese State Councilor and FM Yi (R) have a meeting on April 24, 2018 in Beijing, China. MADOKA IKEGAMI / Pool / Getty Images

The Chinese government issued an official document on March 28, 2015 with the layout of the major principles and priorities for the BRI. The initiative has since been extensively discussed among academics and policymakers both inside and outside of China.32

Kazakhstan-China collaboration is characterized by high dynamics of contacts at the highest levels, and an imposing legal base. The legal base of this bilateral relation consists of more than 230 contracts and agreements in different areas, among which are the most fundamental agreements as the Treaty of Good-Neighborliness and Friendly Cooperation signed in December 2002 in Beijing and the Joint Declaration of the heads of state of the Republics of Kazakhstan and China on a new stage of comprehensive strategic partnership (August 2015, Beijing).

Public Perception of BRI in Kazakhstan

China is focused on how the BRI was perceived in Kazakhstan and other countries directly involved in the project and how these perceptions shaped responses to the initiative. It is obvious that China is aware of the “China threat” thesis that has spread in the whole world and which became visible after the growth of China’s economic power and military capabilities. Currently, China set the task to neutralize the negative reaction abroad with the grand integrative initiative –the BRI, through formation of a positive international image of the country. One of the areas of impact of the “soft power” of China in the region is the education system. Chinese investments into the education sector (including scholarships) increase the student acceptance rate into the Chinese colleges and universities, as well as the rate of sending students to study in universities of Kazakhstan, opening of the Confucius Institutes and active promotion of the study of the Chinese language. As a result, over the past 10 years the number of students from the Central Asian countries in China increased dramatically, and Kazakhstan is the leader among them. Unlike the previous projects, the BRI, and particularly, the NSREB project is being covered as widely as possible in the Kazakhstani mass media. Chinese institutions and organizations in Kazakhstan are organizing and funding a variety of cultural (concerts, exhibitions, etc.) and scientific events (conferences, workshops, research projects), cooperating with Kazakhstani organizations and institutions aimed at discussion and clarification of the Chinese BRI initiative. At the meetings of this nature both sides have a chance to make recommendations on solving certain problems together.

It is both necessary and worth examining a public perception of the BRI project in Kazakhstan. Kazakhstan is the country where alarmist and sinophobic sentiments in regards of the issues of migration and bilateral trade are present. Moreover, China continues to purchase the shares of major Western companies operating in Kazakhstan.33

According to the sociological surveys in 2007 and 2012 (number of surveyed respondents in 2007 is 588, number of surveyed respondents in 2012 is 544) Kazakhstanis’ attitude towards Chinese immigrants had worsened over the past 5 years. 31 percent of respondents believe that the Chinese pose a serious competition in the labor market of Kazakhstan (2012). Kazakhstanis’ public awareness of China, according to the surveys of 2007 and 2012 increased from 21 to 23 percent.34

China alone cannot make the BRI a success, since it covers vast areas involving more than 60 countries. For China, it is a grand strategy, but to its partners, it is really a grand initiative

Several labor conflicts of a local character between Kazakh and Chinese workers occurred in Atyrau and Aktobe regions in 2010, 2013, 2015 35 –the conflicts have not been analyzed by experts and were sparingly reported in the media, which may cause repetition of the conflict and an escalation of tension. In 2014, the former First Deputy Prime Minister of Kazakhstan, Bakytzhan Sagintayev, reported that Kazakhstan’s land would be given for rent to the citizens of the PRC.36 This caused several public resentments such as public censure and formal complaints. As a result, the former Prime Minister officially denied this information.37 Obviously, not only the local workers of the joint Kazakh-Chinese enterprises express dissatisfaction with the distribution of financial resources between the Kazakh and the Chinese workers, but also the whole society, preventing potential projects such as renting land to China.

Large numbers of people protested in Kazakhstan over proposed land reforms on April 2016. The protests against changes to the country’s Land Code have spread across the country. The changes in the law that allow foreigners to rent agricultural land in Kazakhstan for 25 years. First, people in the city of Atyrau in western Kazakhstan took to the streets. Then, demonstrations occurred in Aktobe in the north and in Semey in the east. Some observers estimated that between 1,000 and 2,000 people gathered in each city, which is quite serious for Kazakhstan. The law fuels one of the protesters’ biggest fears -that Chinese investors will come and buy out their land. Many fear that Kazakhstan, with a population of 18 million, will lose out to its bigger neighbor. After the government created the special Committee on the Land Code Changes, the latter didn’t approve the law that allows foreigners to rent agricultural land in Kazakhstan.38

However, initial public perception dominating in Kazakhstan comes mainly from the public newspaper articles with wider circulation in the country. While the BRI is ostensibly aimed at promoting cross-border infrastructure connectivity and further economic connection between China, its neighbors and trading partners, its similarity with Kazakhstan’s own “Nurly Zhol” program was a subject of many commentaries and analyses in the mainstream Kazakhstani media such as “Kazakhstanslaya Pravda” amongst others. It should be noted that the majority of the aforementioned projects lately were included into the “Nurly Zhol” state program of infrastructural development of Kazakhstan for 2015-2019, which were presented by the President of Kazakhstan on November 11, 2014. Therefore, the NSREB project could be considered as a first attempt of the Kazakh government to systematize and streamline the infrastructural projects in the country.

China’s elite have determined Kazakhstan as an ultimate bridge linking the mainland with the main BRI land points, thus, positioning it as one of Eurasia’s most promising centers and making it a prime location for observers

In one of the mainstream Kazakhstani newspapers “Egemen Kazakhstan,” Kazakhstan is viewed as the bridge between the East and the West, and the BRI is viewed as an essential competitive advantage as the country aims to double the volume of transit along the East-West route by 2020. In this regard, the authors note that the NSREB project opens wide perspectives for developing trade, economic, and investment cooperation among states, in particular for Kazakhstan. Thus, to decrease the costs and the time spent on transportation of the goods from China to Europe, China can use the route through the territory of Kazakhstan, which can reduce the transportation time from 45 days to 10-14 days.39 Therefore, it is a “win-win” situation for both sides since it offers the construction of a multimodal transcontinental corridor, which is a guarantee of high connectivity and high standard infrastructure facilities.

More importantly, the theme of the BRI’s similarity with Kazakhstan’s own “Nurly Zhol” project is obviously a widely covered topic.40 And yet, the Kazakhstani public opinion is still silent on this matter, except for the analysts of think tanks, observers, students of Chinese studies or international relations, and journalists. One of the major reasons for this paradox might be the absence of wider public awareness in Kazakhstan as Kazakhstani people do not possess enough and detailed information about the BRI project, in particular, the NSREB. Such an outcome should be expected and is quite natural, taking into consideration the fact that it is one of the very recent initiatives and it, in turn, requires some time to process the information. Consequently, there are no major sociological studies such as opinion polls, questionnaires done in Kazakhstan in assessing the public view on this matter.

Since the realization of the BRI project will allow establishing a powerful economic corridor with an enormous potential for development, journalists echoed the analyses of the reinvigoration of the existing international institutions such as the SCO, the EEU and even the EU, thereby, stating that the creation of other international institutions in the future is inevitable.41 An article in the Kazakhstani “Liter” newspaper highlights the stabilizing effect of the BRI project, in particular, the NSREB in Central Asia, as they argue that it presented a potential of hindering the dissemination of extremism, terrorism, and religious fundamentalism. Some think that such a scenario was possible because the implementation of the NSREB project would eliminate the social underpinnings that give rise to such destabilizing phenomena in the first place.42

The public perception in Kazakhstan, which in turn, stem from the articles, analysis, and official statements, presented in the state newspapers, media, and internet news sources, are in favor of the implementation of this project. The mainly positive view is focused on the economic benefits (in particular infrastructure construction and increased trade volumes) and possible stabilizing effects of the BRI project in the realm of security. However, some observers doubted Kazakhstan’s enthusiasm by arguing that Astana’s commitment towards the EEU would not allow it to approve the project, let alone participate in its realization. Also, the analyzing of surveys on public perception of the Chinese activity in Kazakhstan shows differing attitudes, from negative to neutral. However, Kazakhstan is likely to become the major contributing partner of China in its BRI project, in particular, its continental part –the “Silk Road Economic Belt.” In doing so, the two regional projects –the EEU and the BRI– can be complementary in organizing the new economic, infrastructural landscape of Eurasia. As many have noted the coexistence of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the 21st century Maritime Silk Road in the Asia-Pacific Region, the coexistence of the EEU and the NSREB is quite possible. It might be the case, since both –the EEU and NSREB– share a common goal of enhancing the free movement of goods, services, people and capital. In doing so, these two overlapping regional projects can comprise the software (EEU with its rules and regulations) and the hardware (NSREB with its highways, railways and bridges) of economic activities in the Eurasian continent. China alone cannot make the BRI a success, since it covers vast areas involving more than 60 countries. For China, it is a grand strategy, but to its partners, it is really a grand initiative. As an initiative, it needs an active participation and close cooperation of all related partners. Kazakhstan, as a developing economy, mostly accepts the BRI as a mechanism of coordinating economic development strategies and policies with plans and measures on enhancing connectivity through building infrastructure networks and integrating construction plans and systems of technical standards.

Conclusion

Thus, China and Kazakhstan share common interests in the economics and politics field. Kazakhstan supplies hydrocarbons necessary for China and it is ready to become the trade bridge between China and Western Europe. China’s elite have determined Kazakhstan as an ultimate bridge linking the mainland with the main BRI land points, thus, positioning it as one of Eurasia’s most promising centers and making it a prime location for observers. It is clear that a key goal for Chinese investors in Kazakhstan is to secure overland deliveries of energy resources to China by inland routes alternate to maritime shipments, which means that Beijing also has a geopolitical interest in strengthening energy cooperation with Kazakhstan. It is necessary to note, that in the context of the global financial crisis, China has become the largest creditor and the investor for Kazakhstan, bypassing both Russia and the countries of the West. Despite the creation of the EEU, China remains the major trade partner of Kazakhstan. Within the BRI Initiative, the two countries are developing infrastructure facilities for bilateral trade. At the same time, part of Kazakhstan’s elite, which is not related to the oil-and-gas sector, suspect the PRC has latent intentions towards Kazakhstan’s resources (including land). The Chinese migration to Kazakhstan is a subject of special concern for Kazakhstan’s experts. Moreover, Beijing is concerned that public opinion in Kazakhstan perceives China as a source of threat to its national security. According to estimates of the two leaders, almost complete understanding was reached in ensuring regional security.

Chinese foreign diplomacy will become more active and such institutions as the SCO and NSREB mechanism will provide important support to international problems in the near future, representing the one center of the multi-polar world and the non-Western values and principles

In conclusion, China now urges a greater geopolitical role in the world. Currently, it presents SCO as an active and dynamic alliance that primarily seeks to promote itself to the world as a guardian of global and regional security. For China, the SCO and NSREB provide a useful multilateral platform for the implementation of its economic initiatives. Now the SCO area of responsibility covers an area inhabited by over 3 billion people –about 1/3 of the world’s GDP. Thus, the organization entered a new stage of its institutional development as the “Shanghai Eight.” In this institutional dimension, China has more freedom to play, since it has economic power, international reputation and credibility. China is still in the process of developing the comprehensive and multidimensional approaches of its New Diplomacy through the SCO and NSREB. However, there is no doubt that with its New Diplomacy, China will aim to guide the SCO member states and NSREB countries in their political and economic activities. It is clear that Chinese foreign diplomacy will become more active and such institutions as the SCO and NSREB mechanism will provide important support to international problems in the near future, representing the one center of the multipolar world and the non-Western values and principles.

Endnotes

- Gao Fei, “The Shanghai Cooperation Organization and China’s New Diplomacy,” Discussion Papers in Diplomacy, No. 118 (2010), p. 3.

- Madalina Antonescu, “The New Chinese Security Concept and the ‘Peaceful Rise of China,’ as Two Basic Pillars of the Contemporary Chinese Foreign Policy,” Polis, Vol. 1, (2015), p. 2.

- “The SCO Countries Signed Memorandums on Accession of India and Pakistan,” Ria, (June 24, 2016), retrieved July 28, 2016, from https://ria.ru/world/20160624/1450882403.html.

- Ai Yan, “SCO to Expand for First Time in 2017 Summit,” CGTN, (August 6, 2017), retrieved September 8, 2017, from https://news.cgtn.com/news/3d6b544f3545444e/sharep.html.

- Stephen Aris, “The Shanghai Cooperation Organization: ‘Tackling the Three Evils’ a Regional Response to Non-traditional Security Challenges or an Anti-Western Bloc?” Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 61, No. 3 (2009), p. 462.

- Yu Jianhua, Studies on the Nontraditional Security of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, (Shanghai: Shanghai Social Tactics Preface Press Co., 2009), p. 21.

- Alexander Cooley, “The League of Authoritarian Gentlemen,” Foreign Policy, (January 30, 2013),

retrieved January 30, 2013, from http://foreignpolicy.com/2013/01/30/the-league-of-authoritarian-

gentlemen/. - Ariel Cohen, “The Dragon Looks West: China and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization Heritage Lectures,” Report Asia Heritage Foundation, No. 961, (August 3, 2006), p. 4.

- Fredrick Stakelbeck, “A New Bloc Emerges?” The American Thinker, (August 5, 2005), retrieved from http://www.americanthinker.com/2005/08/a_new_bloc_emerges.html.

- Richard Weitz, “The Shanghai Cooperation Organization: A Fading Star?” (August 11, 2014), retrieved

July 28, 2016, from http://www.theasanforum.org/the-shanghai-cooperation-organization-a-fading-star/. - Daniel Miller, “The Shanghai Cooperation Organization and the People’s Republic of China: Security Function Growth Is Occurring along Anti-Terrorism Lines,” Master Thesis, University of Washington, 2014, p. 67; Weitz, “The Shanghai Cooperation Organization: A Fading Star?”

- For a brief overview see, Chien Chung, “China and the Institutionalization of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization,” Problems of Post-Communism, Vol. 53, No. 5 (2006), pp. 3-14; Pan Guang, “A New Diplomatic Model: A Chinese Perspective on the Shanghai Cooperation Organization,” Washington Journal of Modern China, Vol. 9, No. 1 (2008), pp. 55-72; Jing-Dong Yuan, “China’s Role in the Establishing and Building the Shanghai Cooperation Organization,” Journal of Contemporary China, Vol. 19, No. 67 (2010), pp. 855-869.

- Alyson Bailes et al., “The Shanghai Cooperation Organization,” SIPRI Policy Paper, No. 17 (2007), pp. 45-58.

- Joseph Cheng, “China’s Regional Strategy and Challenges in East Asia,” China Perspectives, No. 2 (2013), pp. 53-65.

- Wu Hongwei, “Feasibility Analysis of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization to Establish a Free Trade

Zone,” in Wu Hongwei and Jinfeng Li (eds.), A Strategy for Security in East Asia: Shanghai Cooperation Organization, (New Delhi: Social Science Literature Press Co., 2013); 吴宏伟.上海合作组织建立自由贸易区可行性分析《上海合作组织发展报告 (2013)》, 社会科学文献出版社2013“¥9月第1版 retrieved September 19, 2014 from http://studysco.cass.cn/shyj/jjhz/201311/t20131125_880359.html; 上合组织开发银行中国全面金融外交的新设想. 银行业研究 2014.09.19 第 126 期; SCO Development Bank, “New Ideas of China’s Comprehensive Financial Diplomacy,” ICBC Report, retrieved September 19, 2014, from http://www.icbc.com.cn/SiteCollectionDocuments/ICBC/Resources/ICBC/fengmao/download/2014/shanghezuzhikaifayinhang.pdf. - Wang Haiyan, “Regional Economic Cooperation in Central Asia under the Framework of Shanghai Cooperation Organization,” Journal of Xinjiang Normal University (Social Sciences), No. 2 (2008), p. 42.

- Joint Statement between the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China on Cooperation in Construction of Conjugation of the Eurasian Economic Union and the Silk Road Economic Belt, (May 8, 2015).

- “The Conjugation of the EEU and NSREB: A List of Infrastructure Projects Has Been Agreed,” Eurasian Comission, (March 1, 2017), retrieved March 6, 2017, from http://www.eurasiancommission.org/en/Pages/default.aspx.

- Weiqing Song, China’s Approach to Central Asia: The Shanghai Co-operation Organisation, (New York: Routledge, 2016).

- “Chinese, Foreign Politicians, Scholars Discuss New Implications of Five Principles,” 人民日報,

[People’s Daily], (June 16, 2004), retrieved from http://en.people.cn/200406/14/eng20040614_146323.html. - Sanat Kushkumbaev, “The Development of SCO as a Regional Organization: A Potential of Expansion,” Kazakhstan Institute of Strategic Studies, retrieved March 7, 2015, from http://kisi.kz/uploads/33/files/IFsnVG98.pdf.

- Weiqing Song, “Interests, Power and China’s Difficult Game in the SCO,” Journal of Contemporary China, Vol. 23, No. 85 (2014), pp. 85-101.

- Meena Roy, “Dynamics of Expanding the SCO,” Institute for Defense Studies and Analyses, retrieved February 4, 2016, from https://idsa.in/idsacomments/DynamicsofExpandingtheSCO_msroy_040411.

- “President of Kazakhstan Suggested Creating the SCO Free Trade Zone,” Kazakhstan’s Truth, (June

9, 2017), retrieved from https://www.kazpravda.kz/en/news/economics/kazakh-president-suggested-

creating-free-trade-zone-in-sco. - “Participation in the Opening Ceremony of the ‘One Belt and One Road’ Forum for International Cooperation,” retrieved February 8, 2018, from http://www.akorda.kz/en/events/international_community/foreign_visits/participation-in-the-opening-ceremony-of-one-belt-and-one-road-forum-for-international-cooperation.

- “KNR: Priezzhajte k nam i Torgujte,” The National Chamber of Entrepeneurs of the Republic of Kazakhstan “Atameken,” (October 14, 2015), retrieved January 27, 2018, from http://atameken.kz/ru/news/24598-eksportiruj-v-kitaj.

- Dmitriy Frolovskiy, “Kazakhstan’s China Choice,” The Diplomat, (July 6, 2016), retrieved March 7, 2018, from https://thediplomat.com/2016/07/kazakhstans-china-choice/.

- Chen Jia, “Economic Projects Assist Belt and Road Initiative,” China Daily, (May 8, 2015), retrieved

June 14, 2016, from http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/cndy/2015-05/08/content_20654226.htm. - “Over 80% of Trains from China to Europe Pass through Kazakhstan,” Kazinform, (June 1, 2017), retrieved from http://www.inform.kz/ru/svyshe-80-poezdov-iz-kitaya-v-evropu-prohodyat-cherez-kazahstan_a3031902.

- Xi Jinping, “May China-Kazakhstan Relationship Fly High toward Our Shared Aspirations,” China Daily, (June 8, 2017).

- Wang Yi, “Belt and Road Construction Has Achieved a Series of Important Early Harvest,” Ministry

of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, (July 28, 2016), retrieved from http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/t1365955.shtml. - Zhang Yunling, “One Belt, One Road: A Chinese View,” Global Asia, Vol. 10, No. 3 (2015), p. 8.

- Konstantin Syroezhkin, “China’s Presence in Kazakhstan: Myths and Reality,” Central Asia’s Affairs,

Vol. 1, No. 42 (2011). - Elena Sadovskaya, Kitajskaja Migracija v Central’noj Azii v Nachale XXI veka, Ekonomicheskoe Nastuplenie i Migracija iz KNR na Primere Respubliki Kazahstan: Vyzovy i Vozmozhnosti (Chinese Migration in Central Asia at the Beginning of the XXI Century Economic Offensive and Migration from China to Kazakhstan: Challenges and Opportunities), (Mauritius: Lambert Academic Publishing, 2012), p. 32.

- “Akim VKO Prokommentiroval Massovuju Draku Kitajskih i Kazahstanskih Rabochih v Aktogae,” Tengrinews, (December 14, 2015), retrieved January 17, 2017, from https://tengrinews.kz/kazakhstan_

news/akim-vko-prokommentiroval-massovuyu-draku-kitayskih-285743/. - “Kazahstan Dal Zemlju v Arendu Grazhdanam Kitaja,” Nur, (May 13, 2014), retrieved May 15, 2016, from https://www.nur.kz/313398-kazahstan-dal-zemlyu-v-arendu-grazhdanam-kitaya.html.

- “Karim Masimov Oproverg Svedenija o Jakoby Peredache Zemel’ Kitaju,” Zakon, (December 14, 2009), retrieved July 22, 2016, from https://www.zakon.kz/157021-kazakhstan-ne-budet-prodavat-zemlju.html.

- “Kazakhstan’s Land Reform Protests Explained,” BBC, (April 28, 2016), retrieved May 9, 2016, from http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-36163103.

- Nurgul Salykzhanova, “Geograficheskoe Polozhenie Kazakhstana Daiot Bol’shie Preimuschestva

(Geographic Location of Kazakhstan Offers It Great Potentials),” Liter Newspaper, (July 29, 2015), retrieved from https://liter.kz/ru/articles/show/11035-geograficheskoe_polozhenie_kazahstana_da_t_bolshie_preimushestva. - “Ekonomikalyk Integracia” (Economic Integration), Egemen Kazakhstan Newspaper, (October 7, 2015).

- Sergey Konstantinov, “Odin Poyas – Odin Put’ – Eto ne Solo, a Symfonia (BRI – Is Not Solo, Rather a Symphony),” Liter Newspaper, (March 27, 2015).

- Nurlybek Dosybai, “Zhibek Zholy Ayasynda Kytai Kozdeitin Bes Maksat, Ush Bagyt (Five Goals, Three Directions of China within Silk Road Project),” retrieved April 17, 2015, from https://baq.kz/kk/news/alem-ekonomikasi/zhibek-zholi-ayasinda-kitai-kozdeitin-bes-maksat-ush-bagit-63849.